Risk Perception Moderates How Knowledge is Translated into Intentions to take Preventive Measures against NonCommunicable Diseases NCDs)

- 1. Department of Psychology, Debre Birhan University, Ethiopia

- 2. School of Psychology, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

INTRODUCTION

People are assumed to enhance instigated to select strength presence if they hear about and associate risk accompanying ongoing to perform their fitness-agreeing conducts. Several hypotheses accept the duty acted by well-being risk understanding. For instance, the Health Belief Model [1], the Protection Motivation Theory [2], the Precaution Adoption Process Model [3], and the Health Action Process Approach [4], grant risk estimation expected individual of the conditions for making an goal to act. However, the pertinence of risk idea may again disagree as a function of the information about the risk and address fitness act. In a meta-reasoning [5], it is disputed that risk idea is more influential for nature that help the decline of a energy danger, are less compulsive external influences, and are smooth to act (for example halting from drugs) than for complex management in the way that exercise and active consuming practices.

Knowledge

As NCDs are individual of the important well-being and happening challenges we face contemporary, fact-finding a accompanying idea will lead to a deep understanding of the question and probing for an active answer like discovery, hide, situation, and relief care. Particularly, Ethiopia’s fitness structure is active to implement knowledge-lifting programs on NCDs and risk determinants for various divisions of the society (MOH, 2021). Without information about NCDs and their risk factors, it is troublesome to solve a decline in the occurrence and predominance of NCDs (Thippeswamy and Prathima, 2016). As a result, deciding the level of information about NCDs stresses the meaning of attending routine following for NCDs’ risk determinants and introducing stop programs (Gamage and Jayawardana, 2017).

Protection motivation

Unhealthy way of life places an character at danger for growing NCDs [6], which can be coming to be notably universal in the young adults population [7]. Lowering threat factors or adopting easy protecting measures including physical exercise on a regular foundation ought to help prevent maximum of NCDs and their effects [8,9]. But, best 29–50% of people’ showcase ‘good enough’ stages of sun protection based totally on country-precise solar safety pointers [10]. For that reason, it is vital to discern out how humans emerge as stimulated to have interaction in these behaviors. Risk perception has been proven to be a extensive predictor of both aim and conduct within the context of NCDs protection [10-13]. A take a look at based totally on PMT found that danger appraisal constitutes a higher predictor of NCDs protection aim in contrast to coping appraisal, while previous performance of comparable behavior emerged as the strongest predictor of aim accompanied by means of perceived vulnerability to growing NCDs [14]. Furthermore, risk perception has been shown to are expecting conduct together with sunscreen use and seeking shade in a pattern of Ethiopian adolescents [15]. In addition studies has shown that human beings are more vulnerable to protect themselves from the sun while perceiving a higher threat, while their appearance might suffer due to unprotected sun exposure in addition to when understanding a person diagnosed with NCDs [16].

Then again, being aware of brief-term risks of NCDs collectively with valuing a tan, and unrealistic optimism impact the selection not to take safety measures [17]. Based totally at the results in their qualitative study on younger humans from New Zealand, the authors argue that even though human beings are informed about the risks of NCDs, have high self-efficacy, but lack perceived chance they’ll no longer act due to the fact they may be not influenced to do so.

Recommendations are made to cope with the imbalance between danger appraisal and outcome expectancies, emphasizing the fast time period negative consequences of exposure to the danger elements which will sell preventive behavior. despite the fact that, how are we able to pleasant develop motivation for protection and help encouraged people to act upon their intentions? A study at the usefulness of ranges of alternate in developing sun protection motivation showed that hazard appraisal records facilitated the transition from pre-contemplation to contemplation, while as a way to take the plunge from contemplation to instruction, humans wanted excessive chance and excessive coping records [18].

Some other have a look at observed that the decisional stability, defined because the competing assessment of the pros of exposure to risk factors and professionals of NCDs protection, represents a mediator of an intervention to growth protection in youngsters [19]. The effectiveness of tailor-made customized chance remarks on increasing safety practices has additionally been tested for the ones people with high chance of growing NCDs [20]. Furthermore, outcomes of studies that investigated the mechanisms that accounted for the achievement of safety intervention in changing conduct observed that knowledge about exposure to risk factors and protection techniques, sunscreen use limitations and self-efficacy acted as mediators of a solar protection intervention for middle college youngsters [21].

Similarly research confirmed that expertise, social norms, perceived chance, self-efficacy, and perceived bad consequences of publicity to risk factors accounted for 44% of the variance in aim to take preventive measures, while making plans and intention predict sunscreen use. Furthermore, there may be help for a mediating and moderating impact of planning on aim to take preventive measures, arguing for the inclusion of put up-intentional factors in a model explaining safety [22,23]. Consequently, maximum theories do not forget chance belief a predictor of aim, and there may be proof that danger notion enables the development of a sun safety goal.

However, does hazard belief keep to play a function even after people are prompted to behave, and does it help them to translate intentions into actions by way of planning? And in that case, what’s the mechanism through which it impacts making plans and behavior adoption?

Risk perception

People often underestimate their hazard of growing illness. A sense of vulnerability is lacking, and therefore they won’t take precautions (Renner and Schupp in press). Threat belief can be subdivided into absolute and comparative hazard belief. Absolute danger perception refers to at least one’s subjective probability of adversity inclusive of ‘‘i am at hazard for NCDs’’ whereas comparative risk belief reflects the distinction between the perceived risk for oneself in preference to that for others (e.g., ‘‘i am more at risk of NCDs than different people of my age and gender’’). Underestimating one’s health danger either manner has been conceptualized as the ‘‘optimistic bias’’ [24,25]. Consequently, the construct of danger perception may be considered part of the circle of relatives of optimism constructs.

Unrealistic optimism refers back to the tendency to perceive oneself as being invulnerable or much less prone than others to poor life occasions [24,25], or health threats and is related to taking less action to alternate behaviors [26]. This biased perception of fitness risks (unrealistic optimism, nice phantasm) has been interpreted as ‘‘protecting’’ optimism as opposed to ‘‘practical’’ optimism [27,28]. useful optimism is based on beliefs about one’s resources, inclusive of capacity and attempt to address adversity. One example is the dispositional optimism assemble, embedded within the self-regulation theory of Carver and Scheier [29]. it is based totally on generalized outcome expectancies (e.g., ‘‘there is continually a silver lining’’) and includes an effort to gain valued desires (e.g., ‘‘If I take precautions i’m able to stay healthful’’). Dispositional optimists are people who expect highquality results in diverse existence domain names consisting of fitness. They are confident about the destiny and, consequently, invest attempt while facing complication. the other instance of purposeful optimism is perceived self-efficacy [30], that is primarily based on one’s perception in being successful to cope with adversity (e.g., ‘‘i am sure that i’m able to control my fitness even when being challenged via illness’’).

The connection between chance notion and optimism becomes more complicated when additionally considering levels of generality and specificity. Fitness threat perception is a website-particular construct, and the corresponding functional optimism is coined ‘‘fitness-related optimism’’. A observe via Luo and Isaacowitz [31], analyzing how optimists process skin most cancers statistics, observed that dispositional and health-related optimism are expecting fitness-cognitions and behavior in distinct ways. Human beings low in dispositional optimism, described as a belief in exact future effects throughout life domain names, or high in fitness-associated optimism were more responsive to NCDs data when they had been at objective danger of developing NCDs. people excessive in dispositional optimism were much more likely to interact in fitness-promoting behaviors. But, health-associated optimism better expected health information processing and behavior in evaluation to dispositional optimism [32]. Davidson and Prkachin [33], have showed the discriminant validity of unrealistic and fitness-associated optimism while additionally implicating their joint importance as determinants of fitness-promoting behaviors. Within the gift study, low degrees of danger perception pertain to 1’s optimism closer to not growing pores and skin cancer. It desires to be determined whether or not such kind of optimism is dysfunctional or functional for the use of solar display screen whilst being uncovered to the sun.

Mechanisms of fitness behavior change: mediators and moderators

To study how conduct trade takes region, we want to use mediation analyses, and to study for whom a selected exchange mechanism is legitimate, we want to study moderation [34]. Mediation describes how an impact takes place, that is, how an independent variable influences a based variable thru a third variable that constitutes the mediator. A mediator would possibly emerge in a single organization (e.g., human beings perceiving high risk), but not in another (e.g., people perceiving low risk). In the sort of case, threat operates as a moderator of the mediating dating. Excellent intentions are more likely to be translated into action while human beings plan when, wherein, and how to carry out the desired behavior. Intentions foster making plans, which in flip facilitates conduct alternate. Danger perception was observed to mediate the knowledge-aim relation however some studies didn’t find such mediation effects [35]. This shows that the relationships among intentions, making plans, and behavior might also rely on other factors inclusive of threat perception. This represents a case of moderated mediation.

Aims of the study

Previous studies have shown risk perception to be a mediator between knowledge and intention and [22,23]. The present study examines the role of knowledge and risk perception in the domain of NCDs. It is expected that planning mediates the intention— behavior relationship. Moreover, it explores which role risk perception might play. In particular, it is examined whether risk perception operates in conjunction with knowledge as reflected by an interaction between intention and risk perception. Such a moderator effect could shed light upon the mechanisms that operate in the motivational or volitional phases when people adopt or maintain safety measure or habits. The study aims at the change of intention to take preventive measures over time and explores the underlying social-cognitive variables that may be responsible for behavior change. The main question is whether knowledge--intention chain exists and whether this chain is moderated by risk perception and its components.

METHODS

Study design, participants, and sampling

This was an exploratory and cross-sectional study, conducted during March-November 2022 in the Debre Birhan University, main and health campuses. Full-time scholar and day scholar students of Bachelor degree were invited to participate in the survey. Participants representing all three years from different majors were included. A convenience sampling was utilized to recruit the sample of university students.

Measures

Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations are displayed in Table 1. All scales were self-developed and tested prior to being used in this study. Intention to take preventive measures was measured with nine items asking people about their intentions during the next years. Responses ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). 21 items that targeted perceived vulnerability to develop NCDs and perceived severity of developing NCDs were used to assess risk perception. Respondents had to estimate their risk by choosing an answer from very unlikely (1) to very likely (5) for vulnerability and not serious at all to very serious for severity. Knowledge was measured by 19 item questionnaire. Responses ranged from 1 correct, 2, incorrect and 3 I do not know.

Analytical procedure

The analyses were based on procedures recommended by Preacher et al. [36]. A moderated mediator model was tested, where risk perception was chosen as a moderator of the knowledge-intention relationship, using the IBM Amos (version 23) by Preacher et al. [36]. To test the interactions, variables were centered [37]. Moderated mediation is expressed by an interaction between risk perception and knowledge on knowledge [34]. To account for baseline behavior, outcome expectancy was included as a covariate.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for knowledge risk perception components and intention. As depicted in table 1,

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of participants

|

|

Sex |

birth place |

COLLEGE |

study year |

AGE |

knowledge of NCDs |

Risk perception |

Behavioral Intentions |

|

Mean |

1.4132 |

1.5330 |

1.6186 |

2.941 |

22.1222 |

10.3154 |

78.1980 |

33.8484 |

|

Mode |

1.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.0 |

22.00 |

10.00 |

83.00 |

36.00 |

|

SD |

.49301 |

.49952 |

.48633 |

1.0943 |

1.54181 |

4.00377 |

10.34182 |

6.37946 |

|

Min |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

2.0 |

19.00 |

.00 |

37.00 |

9.00 |

|

Max |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

5.0 |

28.00 |

19.00 |

98.00 |

45.00 |

the mode values indicate that most of the participants are male, from town areas, non-health and second year students. The age of participants ranged from 19 to 28. This shows that participants are in the group of young adults.

Knowledge, risk perception and intention difference based on some demographic characteristics

Table 2 shows that

Table 2: Independent sample T-test based on some demographic variables

|

|

t |

df |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

Mean Difference |

|

Behavioral Intentions |

-.702 |

407 |

.483 |

-.44993 |

|

Risk perception |

-.966 |

407 |

.334 |

-1.00365 |

|

knowledge of NCDs |

-.068 |

407 |

.946 |

-.02719 |

|

t-test for Equality of Means based on birth place |

||||

|

Behavioral Intentions |

.822 |

407 |

.411 |

.52015 |

|

Risk perception |

.787 |

407 |

.432 |

.80717 |

|

knowledge of NCDs |

-.278 |

407 |

.781 |

-.11043 |

|

t-test for Equality of Means based on college |

||||

|

Behavioral Intentions |

.345 |

407 |

.730 |

.22433 |

|

Risk perception |

3.166 |

407 |

.002 |

3.29647 |

|

knowledge of NCDs |

7.530 |

407 |

.000 |

2.87876 |

there is no statistically significant difference on the knowledge; risk perception and intention scores based on sex. As of college the students have joined to study being categorized as health and non-health streams showed statistically significant difference among risk perception and knowledge score of participants. The mean of those students who have joined health streams is higher than those form nonhealth for both risk perception and knowledge.

Correlation of the dependent, independent and moderator variables

The correlation between knowledge and intention was positive and significant (r=0.102, p=0.05). The moderator variable has a moderate positive correlation with both the dependent and independent variables (see table 3).

Table 3: Correlation matrix of study variables

|

|

Knowledge of NCDs |

Risk perception |

|

Risk perception |

.156** |

|

|

Behavioral Intentions |

.102* |

.217** |

Moderation results

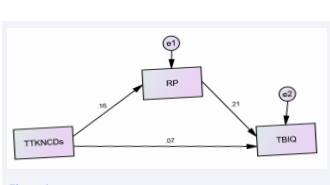

The substantial association between knowledge and intention was partially mediated by the cumulative risk perception of participants. Moreover, an interaction between intention and risk perception became significant, further qualifying the effect of intention on behavior. In this model knowledge have 0.07 (Figure 1),

Figure 1: The basic moderation model.

direct effects on behavioral intention, whereas risk perception has 0.21 direct effect on behavioral intention. On the other hand knowledge has 0.032 indirect effects on intention which makes the total effect 0.102. Thus risk perception partially moderates the link between knowledge and intention.

The mode fit indices of the basic model showed a very good fit NFI=1.00, CFI= 1.00, GFI= 1.00 and REMSEA=0.153. all these values showed the model fit is perfect and there are no modifications needed for this model.

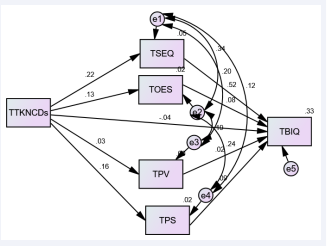

A further analysis was performed to look at the interaction effect in more detail. Figure 2 illustrates the joint effects of risk perception components on intention,

Figure 2: Extended model for components of risk perception.

based on a hierarchical regression analysis with centered predictors and their product term. Knowledge have a significant contribution on on all of the components of risk perception except on perceived vulnerability. On the contrary the model showed that only self-efficacy and perceived severity have significant contribution on intention. The others including knowledge have insignificant contribution on intention.

The model fit indices were not that much good before doing some modifications. As shown in figure 2 some covariance was suggested as a modification. When the covariance was drown the model fit indices improved and proved to good REMSEA= 0.081, NFI= 0.988, CFI 0.991 and GFI= 0.997.

DISCUSSION

The present study has examined the interrelationships between knowledge intention, risk perception in the context of taking preventive measures against NCDs. Starting point for the analysis has been the well-known knowledge __ intention— behavior chain that has been found in many previous studies in different behavioral domains [4,35,38,39]. As expected, it was found that risk perception partially mediates the effect of knowledge on intention.

Previous studies on dietary behaviors as well as physical activity have found that the knowledge-intention-planningbehavior mediation can be moderated by self-efficacy [40,41]. Since the possible development of NCDs after some time constitutes a scary feeling, we had hypothesized that risk perception might constitute a moderator in this case. This indeed materialized in the present data. Risk perception moderated the knowledge- intention relationship.

In other words, the size of the conditional indirect effect varied along levels of the moderator. The moderator effect was positive, reflecting a better mediation when people feel vulnerable. As the figures illustrate, there is no significant effect of knowledge on intentions when risk perception is very low, and thus, there can be no mediation. In contrast, when risk perception is very high, there is a strong effect of knowledge on intentions, allowing for the mediation process.

How can this be explained? Health risk perception can be regarded as the opposite of health-specific optimism, be it realistic or unrealistic optimism [24,25]. When people feel agentic and are optimistic about their control over a health threat they are more likely to consider health actions and perform them [30]. This means that optimistic individuals may well translate their knowledge to intentions. Health-specific optimism, which means low health risk perception, thus, can be a facilitator of health behaviors.

There is a large body of literature that provides ample evidence that optimism is associated with well-being, health, and health behaviors, although the size of these associations is very inconsistent [24-26,28,31,33]. Although ‘‘defensive’’ unrealistic optimism and ‘‘functional’’ optimistic beliefs belong to the same family of optimism constructs, they are clearly distinct and must be separated conceptually and empirically. One reason for such inconsistencies lies in the conceptual diversity of the optimism construct and corresponding psychometric measures.

In the present study, perceived risk provides a proxy measure of health optimism, and an empirical distinction between the different kinds of optimism was not made. This turned out to be a limitation. Future studies should include health-specific defensive optimism as well as functional optimism [27]. Defensive optimism pertains to the neglect of a threat for an immediate self-serving purpose [24,25], whereas functional optimism relates to the belief in one’s competence [30], or effort [29], to cope successfully with a threat. One would expect that only the latter type of optimism would assist in translating intentions into planning for sunscreen use.

Another limitation is the small sample size which does not allow for generalizing the results to a larger population. Future studies are needed in order to explore the role of planning and risk perception in protective measure with larger samples that are representative for a defined population. For a full account of the determinants of protection behaviors, more social-cognitive variables need to be included in a causal model. Measures of the value participants placed on appearance and tanning, and their skin type would also have been of interest. Moreover, results of theory-based interventions such as message framing need to be considered [42,43].

Nevertheless, this represents the first study to address the role played by risk perception in influencing the mediating relation between knowledge and intention to take preventive measures. Results point to the importance of high risk perception or health-specific optimism in the elaboration of plans and behavior adoption. They also have implications for prevention practice as they highlight the relevance of providing planning interventions in conjunction with enhancing optimism to help people transform their sunscreen use intentions into action.

REFERENCES

- Becker MH. The health belief model and sick role behavior. Health Education Monographs. 1974; 2: 401-419.

- Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol. 1975; 91: 93-114.

- Weinstein ND. The precaution adoption process. Health Psychol. 1988; 7: 355-386.

- Schwarzer R. Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2008; 57: 1-29.

- Brewer N, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, McCaul KD, Weinstein ND. Meta-analysis on the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychology. 2007; 26: 136-145.

- Abdulla FR, Feldman SR, Willieford PM, Krowchuck D, Kaur M. Tanning and skin cancer. Pediatric Dermatology. 2005; 22: 501-512.

- Diepgen TL, Mahler V. The epidemiology of skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 146: 1-6.

- Baum A, Cohen L. Successful behavioral interventions to prevent cancer: The example of skin cancer. Ann Rev Public Health. 1998; 19: 319-333.

- Myers LB, Horswill MS. Social cognitive predictors of sun protection intention and behavior. Behavioral Med. 2001; 32: 57-63.

- Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Meiser B. Skin cancer related prevention and screening behaviors: A review of the literature. J Behav Med. 2009; 32: 406-428.

- Arthey S, Clarke VA. Sun tanning and sun protection: A review of the psychological literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995; 40: 265-274.

- Cody R, Lee C. Behaviors, beliefs and intentions in skin cancer prevention. J Behav Med. 1990; 13: 373-389.

- Keesling B, Friedman HS. Psychosocial factors in sunbathing and sunscreen use. Health Psychology. 1987; 6: 477-493.

- Grunfeld E. What influences university students intentions to practice safe sun exposure behaviors? J Adolescent Health. 2004; 35: 486-492.

- De Vries H, Lezwijn J, Hol V, Honing C. Skin cancer prevention: Behavior and motives of Dutch adolescents. Eur J Cancer Prevention. 2005; 14: 39-50.

- Jones F, Harris P, Chrispin C. Catching the sun: An investigation of sun exposure and skin protective behavior. Psychol Health Med. 2000; 5: 131-141.

- Calder N, Aitken R. An exploratory study of the influences that compromise the sun protection of young adults. Int J Consumer Behavior. 2008; 32: 579-587.

- Prentice-Dunn S, McMath BF, Cramer R. Protection motivation theory and stages of change in sun protection behavior. J Health Psychol. 2009; 14: 297-305.

- Adams MA, Norman GJ, Hovell MF, Sallis JF, Patrick K. Reconceptualizing decisional balance in an Adolescent Sun Protection intervention: Mediating effects and theoretical interpretations. Health Psychol. 2009; 28: 217-225.

- Glanz K, Schoenfeld ER, Steffen A. A randomized trial of tailored skin cancer prevention messages for adults: Project SCAPE. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100: 735-741.

- Reynolds KD, Buller DB, Yaroch AL, Maloy JA, Cutter GR. Mediation of a middle school skin cancer prevention program. Health Psychol. 2006; 25: 616-625.

- Jones F, Abraham C, Harris P, Schulz J, Chrispin C. From knowledge to action regulation: Modeling the cognitive prerequisites of sun screen use in Australian and UK samples. Psychol Health. 2001; 16: 191-206.

- Van Osch L, Reubsaet A, Lechner L, Candel M, Mercken L, De Vries H. Predicting parental sunscreen use: Disentangling the role of action planning in the intention-behavior relationship. Psychol Health. 2007; 23: 829-847.

- Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J Behav Med. 1982; 5: 441-460.

- Weinstein ND. Perceived probability, perceived severity and health- protective behavior. Health Psychol. 2001; 19: 135-140

- Radcliffe NM, Klein WMP. Dispositional, unrealistic, and comparative optimism: Differential relations with knowledge and processing of risk information and beliefs about personal risk. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002; 28: 836-846.

- Schwarzer R. Optimism, vulnerability, and self-beliefs as health- related cognitions: A systematic overview. Psychol Health. 1994; 9: 161-180.

- Taylor SE, Brown JD. Positive illusions and well-being revisited: Separating fact from fiction. Psychol Bulletin. 1994; 116: 21-27.

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press. 1998.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman. 1997.

- Luo J, Isaacowitz DM. How optimists face skin cancer information: Risk assessment, attention, memory, and behavior. Psychol Health. 2007; 22: 963-984.

- Aspinwall LG, Brunhart SM. Distinguishing optimism from denial: Optimistic beliefs predict attention to health threats. Personality and Social Psychol Bulletin. 1996; 22: 993-1003.

- Davidson K, Prkachin K. Optimism and unrealistic optimism have an interacting impact on health-promoting behavior and knowledge changes. Personality Social Psychol Bulletin. 1997; 23: 617-625.

- MacKinnon DP, Luecken LJ. How and for whom? Mediation and moderation in health psychology. Health Psychology. Suppl. Issue: Mediation and Moderation. 2008; 27: S99-S100.

- Norman P, Conner M. The theory of planned behavior and exercise: Evidence for the mediating and moderating roles of planning and intention-behavior relationships. J Sport Exercise Psychol. 2005; 27: 488-504.

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res. 2007; 42: 185-227.

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 1991.

- Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Adv Experimental Social Psychol. 2006; 38: 69-119.

- Sniehotta FF. Towards a theory of intentional behavior change: Plans, planning, and self-regulation. Br J Health Psychol. 2009; 14: 261-273.

- Gutierrez-Dona B, Lippke S, Renner B, Kwon S, Schwarzer R. Self- efficacy and planning predict dietary behaviors in Costa Rican and South Korean women: Two moderated mediation analyses. Applied Psychol Health Well Being. 2009; 1: 91-104.

- Lippke S, Wiedemann AU, Ziegelmann JP, Reuter T, Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy moderates the mediation of intentions into behavior via plans. Am J Health Behav. 2009; 33: 521-529.

- Orbell S, Kyriakaki M. Temporal framing and persuasion to adopt preventive health behavior: Moderating effects of individual differences in consideration of future consequences on sunscreen use. Health Psychol. 2008; 27: 770-779.

- Renner B, Schupp HT. The perception of health risk. In H. Friedman (ed), Oxford handbook of health psychology. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press.