Coexistent Neck Enteric Cyst and Intraspinal Neurenteric Cyst: Embryopathogenetic Implications

- 1. Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic

- 2. Department of Clinical and Molecular Pathology, Palacký University Olomouc, Czech Republic

ABSTRACT

Enteric cysts are very rare conditions, occurring mainly in the posterior mediastinum and posterior neck. Their pathomorphology corresponds with that of intraspinal neurenteric cysts. Both formations are derivatives of the posterior foregut. However, their embryopathogenesis has not been elucidated satisfactorily as yet. For those associated with vertebral anomalies, the split notochord theory has been widely accepted. However, this is considered to be hardly conceivable for cases free of these anomalies. Here, a patient with concurrent separated enteric and neurenteric cysts and cervical spine dysmorphism is presented. The review of relevant literature revealed sporadic analogic cases in which a transvertebral communication between the two cysts was present or absent. The latter was associated with a minimal abnormality of vertebral body. The authors suggest that even normal vertebrae may be formed in enteric cysts, which would make the notochord-split theory plausible also for those free of spinal malformation

KEYWORDS

• Embryogenesis

• Enteric cyst

• Neurenteric cyst

• Split notochord

CITATION

Stárek I, He?man J, Salzman R, Szkanderová D (2019) Coexistent Neck Enteric Cyst and Intraspinal Neurenteric Cyst: Embryopathogenetic Implications. Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 6(1): 1230.

ABBREVIATIONS

EC: Enteric Cyst; HE: Hematoxylin Eosin; NEC: Neurenteric Cyst; T2 WI: T2 Weighted Image

INTRODUCTION

Foregut anomalies are sporadic dysembryonal formations. Because of variable anatomical position and histomorphology, they were labeled with different, often confusing terms. In 2009, Sharma et al. [1], proposed their new taxonomy and classification based on unifying concept of suggested embryopathogenesis, categorizing them as duplication cysts, bronchopulmonary foregut malfomations, bronchogenic cysts and foregut and enteric cysts (ECs). The latter (also termed enterogenous cyst, endodermal cyst, gastroenterogenous cyst, gastrocytoma, intestinoma, and archenteric cyst, etc.) are considered to be derivatives of dorsal portion of the foregut that gives origin to the upper part of gastrointestinal tract (including pharynx, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, pancreas, liver and gall bladder). ECs thus comprise two distinct smooth muscle layers and epithelial lining the morphology of which corresponds with that of the dorsal foregut itself or the viscera originating from it. ECs may be incorporated in various GIT organs or isolated in different locations with prevalence in the posterior mediastinum [2-8] and rarely intraabdominaly [9] or in the posterior neck [10,11]. Neurenteric cyst (NEC) is considered to be a variant of EC. It differs from it in occasional presence of ependymal or glial elements, and intraspinal or very rarely, intracranial position. Embryopathogenesis of these cysts has not been elucidated satisfactorily as yet and various theories have been postulated [1,3]. Frequent (40-70%) co-existence with spinal anomalies and persistent attachment to the vertebral column [12,13] suggests that the split notochord theory is at work in the formation of these anomalies. However, this theory fails in cases devoid of split notochord syndrome consisting of vertebral malformation associated with central nervous system and gastrontestinal tract anomalies.

Here we describe simultaneous occurrence of a posterior neck enteral cyst and an intraspinal neurenteral cyst. We believe that our case along with those found in relevant literature would contribute to the embryopathogenesis of these malformations.

CASE REPORT

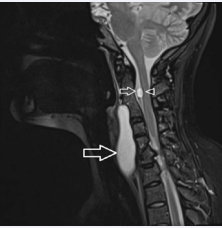

A 29-year old woman presented with a history of headaches and neck stiffness. With the exception of an inconspicuous sinistroscoliosis, the ENT examination was within normal limits. MRI (Figure 1a)

Figure 1: MRI of the neck: a. sagittal plane, T2 WI. A large prevertebral cyst is seen (great arrow). A C2 presumably intradural extramedullar cyst (small arrow) sized 8 mm in the greatest diameter is present causing shallow anterior compression of the spinal cord (arrowhead). Both cysts are non-enhancing, well delineated, isointense compared with cerebrospinal fluid in T2 WI. Normal configuration of the C1 vertebra, C2–C4 posterior synostosis, spina bifida at C5–C6 and hemivertebra C7.

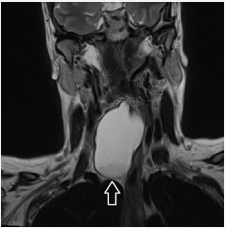

of the neck showed distorted cervical column and a cyst located in the right posterior neck extending down to the Th3 level (Figure 1b).

Figure 1b: Coronal plane, T2 WI. Inferior pole of the neck cyst reaches as far as the thoracic inlet.

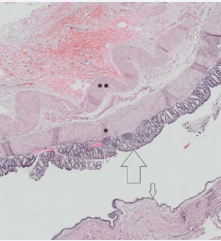

The longitudinal and transversal diameters were 8 by 4 cm. Another small intraspinal cyst lacking any evident connection with the former was also present. The MRI image of the intraspinal cyst met he MRI criteria of neurenteric cysts [14]. The cervical cyst was removed using external approach. It was found to overlie but not to communicate with the thyroid trachea and esophagus. There were neither fibrous connections nor communication between vertebrae and the cyst, the complete removal of which as well as postoperative course was uneventful. Because of the absence of any cord compression symptoms, the intraspinal cyst was left without any neurosurgical intervention. Three years later, the patient is doing well, with no clinical signs of recurrence. Histopathologic analysis of the surgical specimen (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Pathomorphology of the enteric cyst (H.E.). Outer longitudinal (asterisk) and inner circular (double asterisk) layers of smooth muscle are clearly discernible. The cyst is lined with gastric mucosa, the glands of which are composed of columnary epithelium (large arrow), goblet cells are not present. Large parts of the cyst are covered with a flat non-keratinizing squamous cell epithelium (small arrow).

showed a cyst with the wall composed of two layers of a smooth muscle. The cyst was covered with gastric mucosa with continuous transition into a flat non-keratinizing squamous epithelium. No cartilage was found.

DISCUSSION

Association between ECs and spinal abnormalities, supposing a common mechanism involved in their formation was noticed by some early authors [15,16]. Later, it was conclusively proven by Bently and Smith [17] postulating the split notochord theory. This suggests primary split of the notochord as the starting formal event in the development of enteric cysts associated with spinal malformations. The split occurs in a three week embryo that, at that time, is composed of ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal layers. The latter gives rise to the notochordal plate. This is temporarily in contact with dorsal ectoderm and excalates later from the endoderm to form solid notochord that is the primordium of the future axial skeleton. In this pathological scenario, herniation of the endodermal diverticulum through the pre-existing notochord gap and its contact with the ectoderm occur. These events, interfering with normal development of vertebrae, spinal cord and relevant viscera, result in anomalies called posterior enteric remnants. Their eventual nature determined by the extent of the herniation, may be subdivided in fistulae, sinuses and posterior enteric diverticula and cysts [18]. The latter two formations develop when solely an intermediate part of the endodermal diverticulum persists. The remaining part may become atrophic, leaving a fibrous band connecting the cyst to the anterior aspect of the vertebral body. The more or less complete persistent gap in the dorsal embryonic tissues results in associated various spinal malformations (butterfly vertebra, anterior or posterior spina bifida, Klippel-Feil syndrome, diastematomyelia, meningocoele etc).

Other mechanisms for development of an endodermal diverticulum may be abnormal excalation of the notochord from the dorsal foregut [19] and persistent neurenteric canal. However, the latter theory is week. The canal that represents a patent endo-ectodermal passage separating the notochord into two lateral parts is situated in the most caudal aspect of the spine where neurenteric cysts occur very rarely [1]. This drawback eliminates the Bremer´s theory of accessory neurenteric canal that occurs in a more rostral position [20].

All the above mentioned theories are based on the formation of endodermal cells lined diverticulum attached to or separating the notochord. Therefore, they are considered to be applicable only for cysts associated with vertebral malformations. For cases free of them, other more or less acceptable explanations were sought [1,21].

Shreedhar [22], Piramoon [23], Holcomb [24] and Dorsey [25] described posterior mediastinal enteric cysts, expanding intraspinally through a hole in distorted vertebral body. In our patient, the cysts were associated with spinal anomaly but lacked any apparent transvertebral communication. Similar finding was described by Guillery [16] in a baby who died at the age of 3 month from a congenital heart defect. At the autopsy, however, neither epithelial nor fibrous transvertebral connection between the two cysts was found. The author thus postulated early presence of a cyst between the lateral vertebral anlagen. It later becomes snared into two parts by normal fusion of vertebral masses, with minimal or – as we suppose - even no vertebral body malformation and no connection tract left behind. We believe that this hypothesis would explain those cases of isolated enteric cervico-thoracic and intraabdominal cysts published by Andrew [10], Mahore [11] and Kim [9], respectively, in which, because of absent spinal dysraphism, the notochord-split theory could seem implausible.

Despite the similar pathomorphology of a dorsal foregut formation [24], it is not quite clear whether ECs and NECs share identical embryopathogenesis. This hypothesis is supported by the simultaneous presence of both types of cysts. They - as it was in our case and in that described by Guillery [16] - may be entirely separated or communicate through a transvertebral defect [22-26]. In addition, the occurrence of two unrelated dysembryogenetic events in the same patient is hardly conceivable.

FUNDING

The study was supported by MH CZ – DRO (FNOl, 00098892) and the Internal Grant of Palacký University IGA LF 2019-20.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Mr. Ing. Ivo ?berall and Miss Berenika Sou?ková for their technical help during production of this manuscript.