Osteoblastoma of the Jaw: Juggling Jepardy!

- 1. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Karpaga Vinayaga Institute of Medical and Dental Sciences, India

- 2. Head and Neck Oncological Services, Karpaga Vinayaga Institute of Medical and Dental Sciences, India

ABSTRACT

Clinical facts along with radiological and histological findings are imperative to appropriately diagnose lesions of the jaws. Osteoblastoma is an uncommon, benign, primary lesion of the bone that rarely occurs in the

jaw. It presents in the body/ramal region of the posterior mandible and mimics several other swellings which may present at this site. Clinico-pathologically and radiographically there are several lesions that present

with almost similar features. The authors present one such case of a large osteoblastoma in an elderly female stressing the importance of correctly diagnosing these lesions.

KEYWORDS

Osteoblastoma, Diagnostic dilemma, Benign jaw pathology, Bone pathology/swelling

CITATION

Merchant Y, Mohan AM, Balaguhan B, Karthikeyan G (2022) Osteoblastoma of the Jaw: Juggling Jepardy! Ann Otolaryngol Rhinol 9(6): 1304.

INTRODUCTION

Osteoblastoma is a relatively uncommon benign lesion of the bone that accounts for less than 1% of all bone tumors [1]. It commonly involves the spine and sacrum of younger individuals with less than 10% localised to skull [2]. This primary lesion of the bone occurs in young adults with a male predilection (2:1) [1]. In 1956, the lesion was definitely separated from osteoid osteoma and recognised as a separate entity by Jaffe and Lichtenstein under the name ‘benign osteoblastoma’ and subsequently this has been adopted by the World Health Organisation Classification of Bone Tumours [3]. Osteoblastoma of the jaws was first reported in English literature by Borello and Sedano in 1967 [4]. Clinically, the lesion often presents with a bony hard swelling with an obvious facial asymmetry in long-standing lesions. Patients may or may not be symptomatic with pain or discomfort [1]. Radiological evaluation reflects variable features usually exhibiting mixed radiolucency/radio-opacity with relatively defined borders. Reactive sclerosis surrounding the lesion is not generally present. Some lesions present a calcified plaque within the radiolucent area, and some may display considerable calcification [3]. Clinical case capsule, detailed relevant history and radiological findings must be assessed in tandem to appropriately diagnose lesions of the jaws. The authors present a large long-standing asymptomatic osteoblastoma in an elderly female patient that was excised in toto.

CASE PRESENTATION

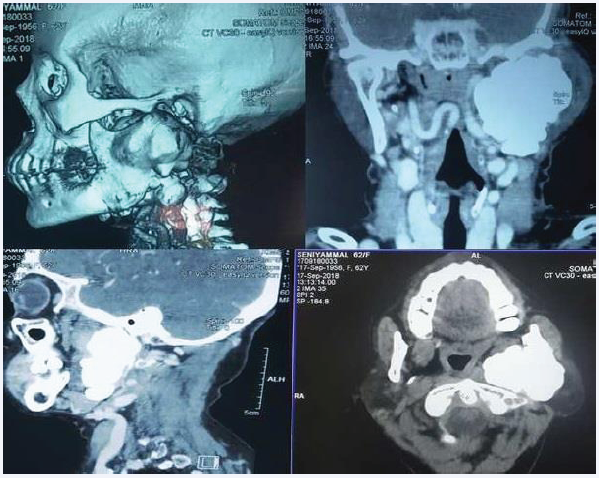

A 62-year-old female reported to the Out-patient Department of our institute with the chief complaint of a bony hard swelling over the left pre-auricular region extending beyond the left angle of the mandible. She reported mild discomfort over the left side of the face and facial asymmetry since the last 1 year. She did not complain of any accompanying pain. On inspection extra-orally, the swelling measured approximately 6 x 4 x 2 cm and extended from the tragus of the left ear to 1cm below albeit in continuity with the left angle of the mandible. Anteroposteriorly it extended from the left buccal region of the face to the skin below and behind the pinna of the left ear. The ear lobe was slightly elevated. The skin over the lesion appeared intact and normal in texture and pigmentation. On palpation, the swelling was bony hard in consistency, immobile and non-tender. The temperature of the overlying skin was normal. No palpable cervical lymphadenopathy was noted. Intra-orally, there were no anomalies/swelling and the buccal mucosa appeared normal. Mouth opening was within normal limits. On palpation the mucosa was pliable with no fibrosis and all findings of inspection were confirmed. A contrast-enhanced CT was advised which revealed a large well-defined high density (HU~1400) bony lesion with a lobulated outline arising from the left ramus and projecting into the masticator and para pharyngeal space. Lesion appeared to be displacing the left Internal Carotid Artery medially and extending up to the styloid posteriorly. Laterally the lesion seemed to be abutting the parotid. Trachea, thyroid and cricoid cartilage appeared normal.

Figure 1: CT scan depicting 3d reconstruction, axial, sagittal and coronal view.

(Figure 1) Left posterior segmental resection of the mandible with disarticulation was planned under General Anaesthesia after routine investigations and anaesthetic fitness. All routine investigations were within normal limits. A modified median lip split incision was made after infiltration with lidocaine and adrenaline (1:2,00,000). The incision was extended along the cervical crease (apron extension) for access (Figure 2a).

Figure 2 a: Incision markingb: Intra-operative view of lesion after reflection of flapc: Intra-operative view of defect post excisiond: Flap sutured back in place

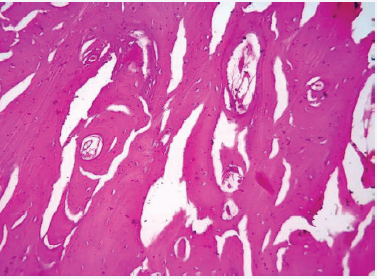

Flap was reflected and the left hemi-mandible was exposed (Figure 2b).Mandible was resected posterior to the last molar under copious irrigation. The lesion was excised in toto. The internal maxillary artery was severed during the procedure and subsequently ligated. Wound was closed in layers with 3-0 polyglactin 910 and 4-0 polyamide after achieving haemostasis. (Figure 3c&d) Sutures were removed on the 7th post-operative day and healing was uneventful. Histopathological examination revealed irregular woven bone like tissue within areas of hypercellular and loose fibrovascular connective tissue stroma Woven bone showed large osteocytes within, along with plump osteoblastic rimming in some sections (Figure 3).

Figure 3: H&E light microscopy.

(Figure 4).

Figure 4: Post OP.

DISCUSSION

Although it is unequivocally agreed that the osteoblastoma is a benign lesion, the true nature of the lesion and the underlying pathophysiology remain an enigma. Some authors regard this entity as an abnormal local response of the tissues to injury or a localised alteration in bone physiology. Osteoblastomas may be classified into cortical, medullary and periosteal types. Osteoblastomas of jaws are either medullary or periosteal and not cortical which are common in extra-gnathic sites [5]. Differential diagnosis’ ranges from cementoblastoma, osteoid osteoma, fibrous dysplasia, ossifying fibroma, focal cementoosseous dysplasia to low grade osteosarcoma. Microscopically and radiographically benign cementoblastoma mimics osteoblastoma.

The feature to differentiate it from osteoblastoma is the merging of the lesion and the radicular surface of the tooth. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma are similar on histopathological examination. However a discerning pathologist would note that the bony trabeculae of osteoblastoma are slightly wider than those of osteoid osteoma and there is less irregularity in their arrangement; the number of osteoblasts is much greater in osteoblastoma but osteoid osteoma lacks giant cells and is not as well vascularized. The most prominent clinical symptom of osteoid osteoma is frequent and severe night pain that responds to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). Clinically, osteoblastoma may be asymptomatic or present with pain which is refractory to NSAID. It presents with neurological pain if the surrounding neurovascular structure is compressed. Osteoblastoma by definition exceed 1 cm in its greatest diameter and is not associated with characteristic oval radiolucency (nidus) with surrounding sclerosis bon sclerosis typical of osteoid osteoma [6]. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma are bone-forming tumors shown to harbour

FOS (87%) and FOSB (3%). FOS immunohistochemistry and / or FISH can be used as an auxiliary tool for osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma in short decalcified tissue where distinction is difficult fromt their histological mimics since there are no specific antibodies or molecular tests for osteosarcoma. [7,8] However, FOS immunohistochemistry should not be used after long decalcification, and the low-level focal expression found in other lesions and tissues, especially reactive bone, might be confusing. Under these circumstances, the use of FISH for FOS could be diagnostically useful, for cases where it is difficult

to distinguish osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma from their histologic mimics [7]. Ossifying fibroma and fibrous dysplasia of bone may share many similarities with osteoblastoma but are less mineralised lesions, revealing fine calcifications rather than large clusters of mineralised material. Fibrous Dysplasia is not circumscribed radiologically and is usually multi-focal [1]. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia (COD) does not typically expand the cortex and microscopically does not depict large numbers of plump, actively proliferating osteoblasts. COD consists of easily fragmented and gritty tissue that can be curetted easily but does not separate cleanly from the adjacent normal bone. In contrast, ossifying fibromas tend to separate easily from the bone [9]. Histopathological examination is the crux to differentiate osteoblastomas from low grade osteosarcomas. Under light microscopy, osteosarcoma is marked by the lack of tumour maturation at the margins, with permeation of tumour into adjacent tissues, in contrast to osteoblastoma which depicts

maturation at the margins and lack of permeation into adjacent bone. In summary, conservative but comprehensive surgical excision of the lesion is the definitive treatment. Recurrence is a rare event (13.6%) and is almost always attributed to incomplete excision. No adjuvant therapy is necessary post excision. It is clear that this benign lesion is unpredictable with behaviour varying from case to case and apparently no special histological features exist that provide clues to the biological behaviour of this neoplasm. Appropriate diagnosis is arrived at in consultation with a radiologist, submission of representative sections to the

histo-pathologist and astute clinical examination.

REFERENCES

1. Huvos AG. Bone tumors - diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Philadelphia, Pa: WB. Saunders Co. 1979.

2. Mirra JM, Picci P, Gold RH. Bone tumors. Clinical, radiologic and pathologic correlations. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1989; 389–430.

3. Capelozza ALA, Dezotti MSG, Alvares LC, Fleury RN, Sant’Ana E. Osteoblastoma of the mandible: Systematic review of the literature and report of a case. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2005; 34: 1–8.

4. Borello ED, Sedano HO. Giant osteoid osteoma of the maxilla. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967; 23: 563–6.

5. Farman AG, Nortje CJ, Grotepass F. Periosteal benign osteoblastoma of the mandible: report of a case and review of the literature pertaining to benign osteoblastic neoplasam of the jaws. Br JOral Surg. 1976; 14: 12-22.

6. Natasja Franceschini, Suk Wai Lam, Anne-Marie Cleton-Jansen, Judith V M G Bovée. What’s new in bone-forming tumours of the skeleton?. Virchows Arch. 2020; 476: 147–157.

7. Lam SW, Cleven AHG, Kroon HM, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Szuhai K, Bovée JVMG. Utility of FOS as diagnostic marker for osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma. Virchows Arch. 2020; 476: 455-463.

8. Baumhoer D, Amary F, Flanagan AM. An update of molecular pathology of bone tumors. Lessons learned from investigating samples by next generation sequencing. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2018; 1–12.

9. Salvi AS, Patankar S, Desai K, Wankhedkar D. Focal cemento-osseous dysplasia: A case report with a review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2020; 24: S15-S18.