Antimicrobial Resistance: A Global One-Health Challenge

- 1. College of Veterinary Medicine, Shaanxi Centre of Stem Cells Engineering & Technology, Northwest A&F University, China.

- 2. Department of Microbiology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Pakistan.

- 3. Department of Computer Science, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Pakistan.

- 4. Faculty of Veterinary sciences, BZU, Pakistan.

- 5. Center of Excellence in Molecular biology, university of Punjab, Pakistan.

- 6. Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Pakistan.

Abstract

AMR, or antimicrobial resistance, is a normal but concerning phenomenon where microorganisms develop defenses against the effects of antimicrobial agents. AMR has gotten worse over the past 70 years as a result of environmental contamination, poor infection control, and the overuse and abuse of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine. The One Health viewpoint is used in this review to address AMR, highlighting the connections between people, animals, and the environment. Poor sanitation, improper use of antibiotics, and lax regulatory frameworks that encourage the selection of resistant strains are major contributors. Mechanisms of resistance such as enzymatic degradation, efflux pumps, and target modification are detailed, with β-lactamase enzymes highlighted as key mediators in drug inactivation. The study also looks at ways to fight AMR, such as vaccination, better farm management, antimicrobial stewardship, and cutting-edge techniques like phage therapy. The review as a whole emphasizes the necessity of a coordinated, multidisciplinary, preventive worldwide response to stop the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Keywords

• Amr

• One Health

• β –Lactamase

• Antibiotic Stewardship

• Phage Therapy

Citation

Rizwan M, Ramzan M, Aslam H, Javaid A, Aslam K, et al. (2025) Antimicrobial Resistance: A Global One-Health Challenge. Ann Clin Med Microbiol 8(1): 1034.

INTRODUCTION

Resistance is the result of numerous physiological and biochemical processes and in case of antimicrobial agents, it is impossible to overestimate the complexity of the mechanisms that lead to the development and dissemination of resistance [1]. Antibiotic resistance is a natural phenomenon in which bacteria evolve defenses against the actions of antimicrobial medications intended to kill or inhibit them. The abuse and overuse of antibiotics in veterinary and human medicine accelerates this process and causes resistant strains to be selected [2]. Over the last 70 years, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has progressively worsened due to a combination of antimicrobial abuse in humans and animals, as well as insufficient research and investment in new antimicrobial drugs leading to increased mortality and morbidity [3]. Among global health issues, AMR most closely illustrates the One Health concept. AMR is a serious global issue that affects people, the environment, animals and national and international security, as well as the global economy [4,5]. Antibiotic resistance is driven by a well-established connection between three domains: human, animal, and environmental health, as a result, tackling antibiotic resistance using the One Health approach makes sense [6]. According to recent data, AMR is developing in conflict areas, where recurring and chronic illnesses, together with a lack of resources, can fuel the development and spread of AMR and create a reservoir of resistance that will be challenging to eradicate [7]. To effectively fight AMR in Pakistan, it is important to focus on prevention in order to stop the spread of disease and lower the need for preventative treatments, especially the wrong prescribing and dispensing of antimicrobials [8]. This review article summarizes the current status of antimicrobial resistance, emphasizing its causes, mechanisms, worldwide effects, and the tactical steps needed to prevent and control it.

CAUSES AND DRIVERS OF AMR

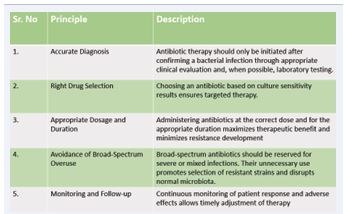

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is becoming a serious threat, and the situation may be made worse in developing nations by widespread misuse of antibiotics [9]. The study found that the global burden of AMR is much greater than the 700,000 annual deaths that the UN and World Health Organization (WHO) have predicted [10]. Whether in humans, animals, or the environment, exposure to antibiotics and other antimicrobial products creates selective pressure that promotes the emergence of resistance, favoring both acquired and naturally resistant strains [11]. Numerous interconnected aspects of agriculture and healthcare control the emergence of AMR through different drug resistance mechanisms [12]. Previous studies have shown that up to 55% of South Africans, 88% of Pakistanis, 61% of Chinese, and 15.4% of Canadians use antibiotics incorrectly in primary care [13]. This overuse of uncontrolled antibiotics along with improper treatment and recycled wastewater are the major causes of AMR [10]. It is essential to recognize and regulate the significance of environmental factors in the genesis and progression of AMR [13]. Agricultural practices, industrial processes, and improper disposal of various medications all frequently release antibiotics and other antimicrobial compounds into the environment [14]. Bacteria try to become resistant to antibacterial medications in order to survive the pressures of environmental selection, making these medications useless [12]. Fundamental risk factors for the establishment and spread of AMR have been identified, including gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, climate, health-care system quality, water sanitation and hygiene infrastructure, along with patient related factors, such as underlying medical conditions, and behavioral factors, such as the overuse of antibiotics to treat viral infections, which may make people more susceptible to infection or less effective antimicrobial medications [15]. High levels of antibiotic usage are found in the healthcare and agricultural sectors, however it is unknown how often this use results in AMR selection, whether a dose-response relationship exists, or the kind and extent of AMR transmission from these environments into clinical settings [16]. The major factors contributing to AMR include the inappropriate use of antimicrobial agents in hospitals, agriculture sector and other environmental reservoirs, however, the amount to which these sources contribute to the genesis, appearance, and spread of AMR has not yet been determined. Without this important, system-wide knowledge, actions cannot be properly optimized or targeted [16]. To mitigate these driving factors, adherence to key principles for the effective and judicious use of antibiotics is essential in both human and veterinary medicine as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Principles for Effective Use of Antibiotics

MECHANISM OF ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE

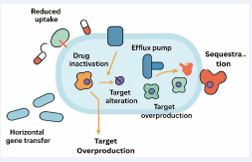

There are several ways that bacteria can show signs of resistance to antibacterial medications. Certain bacterial species have an inherent resistance to at least one class of antimicrobial agents [17]. Antimicrobials can effectively target the bacterial cell wall, bacterial protein and folic acid synthesis, bacterial nucleic acid metabolism, and the bacterial cell membrane [18]. There are five main mechanisms that can be used to explain acquired antibiotic resistance as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Antibiotic Resistance Mechanism

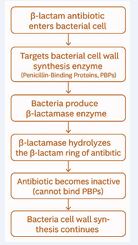

These include lowering cell permeability, modifying an existing target, acquiring a target by-pass system, producing enzymes that render drugs inactive, and removing drugs from cells [18]. One of the most effective and common ways that bacteria resist β-lactam antibiotics is by producing β-lactamase [19]

as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Mechanism of β-lactamase–Mediated Antimicrobial Resistance

Alpha helices, beta-pleated sheets, and other structural similarities are characteristics of globular proteins known as beta-lactamases. The first instance of resistance to a new class of antibiotics resulting from a single amino acid alteration was the “novel” beta lactamases, or ESBLs, present in E. coli and Klebsiella spp. Bacteria [20]. Three methods can be used to make bacteria resistant to β-lactam antibiotics: using β-lactam insensitive cell wall transpeptidases, producing β-lactam hydrolyzing β-lactamase enzymes, and actively expelling β-lactam molecules from Gram-negative cells using efflux pumps [21]. In order to develop new antimicrobial agents or other alternative tools to address these public health issues, it is essential to comprehend the resistance mechanisms of these bacteria [22].

ONE HEALTH INTERVENTIONS TO COMBAT AMR

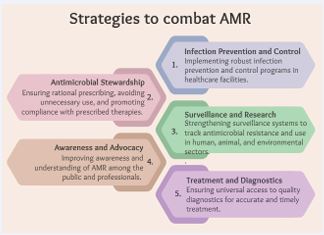

Given the declining efficacy of antibiotics and the emergence of MDROs, it has become crucial to emphasize the significance of controlling and encouraging the responsible use of antibiotics [23]. This involves implementing targeted interventions across human, animal, and environmental sectors to optimize antimicrobial use, prevent infections, and curb the spread of resistance (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Strategies to Combat AMR.

Human Health Sector

Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS): Antimicrobial stewardship is crucial to maximizing the use of currently available antimicrobials due to the slow development of antimicrobials and the rapid emergence and spread of resistant organisms [24]. The term Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) describes the best possible clinical outcome with the least amount of adverse effects on patients and resistance in the future due to the appropriate choice, dosage, and length of antimicrobial treatment [25]. To ensure responsible use of antimicrobials, it is imperative that healthcare professionals receive education and awareness, that prescription-only antibiotic sales be enforced, and that AMR modules be included in medical curriculum [26].

Role of diagnostics: The implementation of the worldwide action plan for AMR containment necessitates a multifaceted and multidisciplinary approach at the interface between humans, animals, and the environment. Microbial culture, hemagglutination inhibition tests, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) are a few examples of traditional detection methods [27]. Traditional diagnostic procedures based on genotypic and phenotypic analysis are costly, time-consuming, and unable to be turned into point-of-care tools, limiting effective disease management and control. However, with advances in molecular techniques, biosensors, and next generation sequencing, rapid and reliable diagnostics are now possible [27].

Animal Health and Agriculture Sector

Prudent Use of Veterinary Antimicrobials: It is generally accepted that the amount of antibiotics used in the livestock industry and the emergence of antibiotic resistance are positively correlated [28,29]. One of the main differences between the use of antibiotics in the human health and livestock sectors is that in livestock sector antibiotics are used primarily as “growth promoters” and for prophylactic purposes. Therefore, it is essential to adopt a restrictive approach and only use antibiotics when absolutely necessary in order to preserve productivity and animal welfare while preserving the effectiveness of antibiotics in livestock farming for curing [30].

Vaccination and Biosecurity: Both WASH and biosecurity interventions might be antimicrobial resistance sensitive. For example, boosting access to clean water and sanitation facilities or assisting farms in implementing biosecurity measures. Both sorts of interventions can be conducted at the system level, thereby influencing risk factors embedded in social structures and addressing socioeconomic vulnerabilities [31]. AMR can be prevented in large part by vaccination, which lowers the overall use of antibiotics by preventing infections from both antibiotic-resistant and antibiotic susceptible bacteria. It is evident that vaccines have been successful in lowering the burden of disease during the past century. Priority should be given to the rapid development of vaccinations that target resistant infections linked to high rates of morbidity and mortality [32].

Good farming practice: AMR has been shown to be significantly influenced by intensive agricultural practices, with conventionally farmed sites containing more AMR genes [33]. For farmers, ranchers, and veterinarians, producing safe and healthy animals for food production is of utmost importance. To stop the widespread use of AMR, it is essential to provide adequate nutrition, maintain a dry, clean environment with adequate ventilation, vaccinate animals against serious diseases, and put potential biosecurity measures in place in farms, trade exhibitions, and marketplaces [34].

Environmental sector Universal implementation of climate change mitigation in healthcare is critical for meeting generally recognised worldwide targets and advancing the sector’s environmental sustainability. Meanwhile, surveillance disruptions and misdirected resources hampered AMR monitoring and control operations. These pandemic related alterations must be carefully examined when analysing the recent global AMR burden, as they constitute both a serious problem and an important lesson for future integrated pandemic-AMR preparedness strategy [35].

CONCLUSION

One of the most important issues facing contemporary medicine, agriculture, and public health worldwide is antimicrobial resistance. Anthropogenic factors and microbial evolutionary processes interact in a complex way to cause the issue: common antibiotic use in humans and animals, inadequate infection control, environmental contamination, and bacterial genetic exchange all contribute to the emergence and spread of resistance. Therefore, a preventive, flexible, and internationally coordinated One Health response is needed to address AMR. Strong antimicrobial stewardship in clinical and agricultural settings, surveillance system expansion and harmonization, tighter control over pharmaceutical quality and disposal, biosecurity and vaccination programs to lower antibiotic demand, and support for new diagnostics and treatments like β-lactamase inhibitors and phage therapy are among the priority actions. Sustained funding for interdisciplinary research, policy enforcement, and education are equally important. The post-antibiotic scenario outlined in this review will become more challenging to prevent in the absence of immediate, consistent, and coordinated actions at the local, national, and international levels. Maintaining the efficacy of antimicrobials for present and future generations requires a shared commitment to these actions.

REFERENCES

- Prasad, BJARCfA. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)-History & Overview. 7.

- Organization WH, W.O.f.A. Health, U. Environment. Antimicrobial Resistance Multi-Partner Trust Fund annual report 2021: Annual report 2023. 2022: World Health Organization.

- Inoue H. Strategic approach for combating antimicrobial resistance(AMR). Glob Health Med. 2019; 1: 61-64.

- Velazquez-Meza ME, Galarde-López M, Carrillo-Quiróz B, Alpuche- Aranda CM. Antimicrobial resistance: One Health approach. Vet World. 2022; 15: 743-749.

- White A, Hughes JM. Critical Importance of a One Health Approach toAntimicrobial Resistance. Ecohealth. 2019; 16: 404-409.

- Aslam B, Khurshid M, Arshad MI, Muzammil S, Rasool M, Yasmeen N, et al. Antibiotic Resistance: One Health One World Outlook. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021; 11: 771510.

- Ghebreyesus TA. Making AMR history: a call to action. Glob Health Action. 2019; 12: 1638144.

- Maryam S, Saleem Z, Haseeb A, Qamar MU, Amir A, Almarzoky Abuhussain SS, et al. Progress on the Global Research Agenda for Antimicrobial Resistance in Human Health in Pakistan: Findings and Implications. Infect Drug Resist. 2025; 18: 3795-3828.

- Ayukekbong JA, Ntemgwa M, Atabe AN. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017; 6: 47.

- Irfan M, Almotiri A, AlZeyadi ZA. Antimicrobial Resistance and ItsDrivers-A Review. Antibiotics. 2022; 11: 1362.

- Khushbu Yadav, Satyam Prakash. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR): Aglobal problem. 2016; 3: 120-138.

- Salam MA, Al-Amin MY, Salam MT, Pawar JS, Akhter N, Rabaan AA, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare. 2023; 11: 1946.

- Irfan M, Almotiri A, AlZeyadi ZA. Antimicrobial Resistance and ItsDrivers-A Review. Antibiotics. 2022; 11: 1362.

- Ifedinezi OV, Nnaji ND, Anumudu CK, Ekwueme CT, Uhegwu CC, Ihenetu FC, et al. Environmental Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Food Safety and Public Health. Antibiotics. 2024; 13: 1087.

- Allel, Kasim, Day Lucy, Hamilton Alisa, Lin Leesa, Furuya-Kanamori Luis, Moore Catrin E, et al. Global antimicrobial-resistance drivers: an ecological country-level study at the human–animal interface. 2023; 7: e291-e303.

- Knight GM, Costelloe C, Murray KA, Robotham JV, Atun R, Holmes AH. Addressing the Unknowns of Antimicrobial Resistance: Quantifying and Mapping the Drivers of Burden. Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 66 : 612- 616.

- Tenover FC. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am JMed. 2006; 119: S3-S10.

- Sefton AM. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance: their clinicalrelevance in the new millennium. Drugs. 2002; 62: 557-566.

- Therrien C, Levesque RC. Molecular basis of antibiotic resistance and beta-lactamase inhibition by mechanism-based inactivators: perspectives and future directions. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000; 24: 251-262.

- Babic M, Hujer AM, Bonomo RA. What’s new in antibiotic resistance?Focus on beta-lactamases. Drug Resist Updat. 2006; 9: 142-156.

- Wilke MS, Lovering AL, Strynadka NC. Beta-lactam antibiotic resistance: a current structural perspective. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005; 8: 525-533.

- Santajit S, Indrawattana N. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistancein ESKAPE Pathogens. Biomed Res Int. 2016; 2016: 2475067.

- Khadse SN, Ugemuge S, Singh C. Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardshipon Reducing Antimicrobial Resistance. Cureus. 2023; 15: e49935

- Doron S, Davidson LE. Antimicrobial stewardship. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011; 86: 1113-1123.

- Shrestha J, Zahra F, Cannady Jr P. Antimicrobial stewardship. StatPearls. 2023.

- Mendelson M, Matsoso MP. The World Health Organization Global Action Plan for antimicrobial resistance. S Afr Med J. 2015; 105: 325.

- Mukherjee R, Vidic J, Auger S, Wen H-C, Pandey RP, Chang C-M. Exploring Disease Management and Control through Pathogen Diagnostics and One Health Initiative: A Concise Review. Antibiotics. 2024; 13: 17.

- Bengtsson B, Wierup M. Antimicrobial resistance in Scandinavia after ban of antimicrobial growth promoters. Anim Biotechnol. 2006; 17: 147-156.

- Chantziaras I, Boyen F, Callens B, Dewulf J. Correlation betweenveterinary antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in food- producing animals: a report on seven countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014; 69: 827-834.

- Magnusson U. Prudent and effective antimicrobial use in a diverselivestock and consumer’s world. J Anim Sci. 2020; 98: S4-S8.

- Pinto Jimenez CE, Keestra S, Tandon P, Cumming O, Pickering AJ, Moodley A, et al. Biosecurity and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions in animal agricultural settings for reducing infection burden, antibiotic use, and antibiotic resistance: a One Health systematic review. Lancet Planet Health. 2023; 7: e418-e434.

- Mullins LP, Mason E, Winter K, Sadarangani M. Vaccination is an integral strategy to combat antimicrobial resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2023; 19: e1011379.

- Kelbrick M, Hesse E, O’ Brien S. Cultivating antimicrobial resistance: how intensive agriculture ploughs the way for antibiotic resistance. Microbiology. 2023; 169: 001384.

- Kasimanickam V, Kasimanickam M, Kasimanickam R. Antibiotics Use in Food Animal Production: Escalation of Antimicrobial Resistance: Where Are We Now in Combating AMR? Med Sci. 2021; 9: 14.

- Aslam B, Aljasir SF. Climate Change and AMR: Interconnected Threatsand One Health Solutions. Antibiotics. 2025; 14: 946.