Exploring the Complex Relationship between Depression and Inflammatory Factors and their Regulatory Mechanisms from the Perspective of Core Inflammatory Mediators

- 1. Affiliated Mental Health College of Inner Mongolia Medical University, China

- 2. Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Mental Health Center, China

Abstract

Depression is primarily characterized by low mood, decreased interest, and anhedonia, along with psychological and somatic symptoms. These symptoms form a multidimensional clinical picture that impairs patients’ social functioning and significantly reduces their quality of life. Accumulating evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between peripheral and central inflammatory responses and depression. This relationship is mediated through mechanisms such as damaging the blood-brain barrier, activating glial cells, and causing neurotransmitter metabolic disorders. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the potential of inflammatory factors as biomarkers for depression, focusing on the core inflammatory mediators—Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Interleukin-2 (IL-2), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-17A (IL-17A), Interleukin-23 (IL-23), and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α)—and their mechanistic links to depression. We critically evaluate recent advancements in the field, integrating findings from preclinical models and clinical studies to elucidate the bidirectional relationship between inflammation and depression. This review also discusses the potential of inflammatory biomarkers for diagnostic and therapeutic applications, emphasizing the need for a more nuanced understanding of the inflammatory pathways involved in depression.

Keywords

• Depression

• Inflammatory Factors

• Interleukin-6

• Tumor Necrosis Factor-Α

• Interleukin

Citation

Yanluan Z, Ma R, Tong L (2025) Exploring the Complex Relationship between Depression and Inflammatory Factors and their Regulatory Mechanisms from the Perspective of Core Inflammatory Mediators. Ann Neurodegener Dis 9(1): 1042.

ABBREVIATIONS

IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta; IL-2: Interleukin-2; IL-4: Interleukin-4; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IL-10: Interleukin-10; IL-11: Interleukin-11; IL-17A: Interleukin-17A; IL-23: Interleukin-23; IL-27: Interleukin-27; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha; NF- κB: Nuclear Factor kappa-light chain-enhancer of activated B cells; JAK/STAT: Janus Kinase/ Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription; HPA: Hypothalamic-Pituitary- Adrenal; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; PPD: postpartum depression; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; SNPs: Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms; TLRs: Toll-Like Receptors; IFN-γ: Interferon-gamma; TGF-β: Transforming Growth Factor-beta; Th17 and Treg cell: T helper 17 and Regulatory T cell; CNTF: ciliary neurotrophic factor; LIF: leukemia inhibitory factor; OSM: oncostatin M; CT-1: cardiotrophin-1; CLC: cardiotrophin-like cytokine; IL-6R: Interleukin-6 Receptor; p38MAPK: p38 Mitogen- Activated Protein Kinase; VTA: ventral tegmental area; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; OUD: opioid use disorder; HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; BBB: blood-brain barrier permeability; STAT3: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor; IKK: IκB Kinase; EP: ethyl propionate; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DAMPs: Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns.

INTRODUCTION

Depression, a major global public-health burden [1], has long had its pathogenesis constrained by the one-sided “monoamine hypothesis,” which can’t explain the treatment- resistant phenomenon seen in up to 30% of clinical patients. WHO statistics indicate depression currently ranks as the principal worldwide source of incapacitation [1]. The heterogeneity and chronicity of its multidimensional symptom clusters (affective- cognitive somatic) highlight the dual challenges of traditional diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in terms of etiological interpretation and intervention precision. In recent years, neuroimmunology has made breakthroughs. It has revealed a bidirectional association between inflammatory responses and depressive phenotypes. Peripheral immune activation reshapes the central microenvironment via the “brain-periphery” interaction network. This opens up a new way to explore the mechanisms of depression [1]. Although numerous studies have confirmed that pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α are significantly elevated in the periphery and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with depression, the neuroregulatory mechanisms remain a subject of key controversy. On one hand, inflammatory factors can induce synaptic pruning abnormalities and neurotransmitter imbalances through glial cell polarization [2]. On the other hand, in specific contexts, these inflammatory factors may exert neuroprotective effects [3]. This “double-edged sword” effect has yet to be systematically elucidated. Furthermore, the efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatments in clinical trials has shown heterogeneity, indicating an urgent need for stratification of inflammatory subtypes and screening of biomarkers. Current research, mostly focused on single pathways, lacks an integrated analysis of the cross scale regulatory network of “immune-neural-endocrine” interactions, which restricts the optimization of targeted intervention strategies. This analysis meticulously analyzes the molecular pathways through which key inflammatory factors like interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) influence monoamine metabolic processes, neuroplasticity, and Hypothalamic-Pituitary- Adrenal (HPA) axis function through dynamic penetration of the blood-brain barrier, vagal nerve signal transmission, and astrocyte-microglia dialogue, up to Octorber 2025, standing at the intersection of multiple disciplines. It also deeply explores their spatiotemporal specificity and dose-dependent effects. By integrating evidence from pre-clinical models with translational medical data, this review focuses on evaluating the potential therapeutic windows and risk boundaries of anti-cytokine therapies, vagal nerve modulation, and nutritional immunological interventions. Finally, it proposes a precision diagnosis and treatment framework based on “inflammatory endophenotypes-multiplex biomarkers-individualized interventions,” providing a theoretical anchor and translational pathway for breaking through existing therapeutic bottlenecks.

Inflammatory Factors and Clinical Findings in Depression

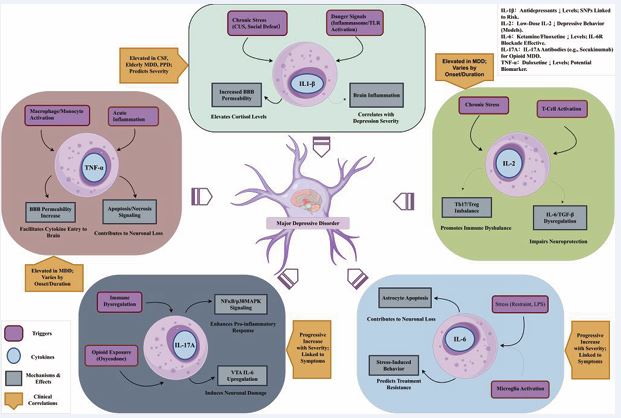

The link between systemic inflammation and major depressive disorder (MDD) is strongly supported by a large body of clinical evidence. Specifically, altered levels of key circulating cytokines have positioned them as promising, albeit complex, biomarkers for the disease. Therefore, this section systematically reviews the clinical research findings for several key cytokines—IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL 17A, and TNF-α—to clarify their respective associations with the diagnosis, severity, and clinical course of MDD (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the main cytokines influencing major depressive disorder (MDD).

IL-1β: The IL1B gene encodes the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. This cytokine was initially tied to sickness behavior, with subsequent research connecting it—alongside IL-6 and TNF-α—to depression [4,5]. In clinical settings, it’s well-documented that depressive episodes often coincide with heightened levels of multiple inflammatory biomarkers [6,7], and researchers have been actively exploring whether IL-1β might serve as a valuable indicator for predicting how patients will respond to depression treatments [8]. Specifically, IL-1β levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are markedly elevated in individuals suffering from unipolar depression and are positively correlated with the severity of depression [9]. Thomas et al., confirmed the link between IL-1β concentrations and depressive symptom intensity: IL-1β levels in elderly (over 60 years old) patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) were significantly increased (by 170%) compared with healthy subjects, and these levels were closely related to the current severity of depression [10]. Corwin et al., reported elevated IL-1β levels in women with postpartum depression (PPD) [11]. A meta-analysis concluded that IL-1β is significantly elevated in patients with depression and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), while IL-6 is only elevated in patients with depression [12,13]. Additionally, a study in Bangladesh also showed that serum IL-1β and TNF-α levels in MDD patients were significantly higher than those in the control group. Their grade of severity was positively associated with the intensity of depressive symptoms, indicating that inflammatory responses are associated with the severity of depression; among them, female patients had significantly higher levels of IL- 1β and TNF-α than male patients. The study suggested that IL-1β and TNF-α could be used as biomarkers for assessing the risk of depression [14]. A recent study on the role of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in promoting the occurrence, severity, and treatment outcomes of depression, it was found that specific genetic variations of IL-1β is linked to depression risk and intensity [15]. Furthermore, studies indicate that interleukin- 1beta (IL-1β) could influence the correlation between mesolimbic pathway connectivity and depressive signs [16]. In summary, clinical phenomena emphasize the central role of IL-1β in depression, which is not only related to disease severity and gender differences but also suggests its potential as a biomarker for diagnosis and risk assessment, helping with early diagnosis and identification.

IL-2: IL-2 is a T-cell growth factor that plays a key role in immune regulation [17]. Clinical observations have shown a close correlation between IL-2 levels and depression: a recent study found that in patients with major depressive disorder, the speed of depressive episode onset (rapid vs. slow) significantly affects serum cytokine levels. Patients with rapid onset and shorter depressive episodes (less than 6 months) had markedly reduced IL-2, Interleukin 4(IL-4), IL-6, Interleukin-10(IL-10), TNF-α, and Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) levels, and other cytokines in their serum. Additionally, patients with shorter depressive episodes (less than 6 months) exhibited lower levels of these serum factors, in contrast to those with longer depressive episodes (6-24 months) [18]. Clinical studies indicate that for individuals battling depression, boosting interleukin-2 (IL- 2) levels throughout therapeutic intervention can lead to a marked reduction in depressive symptoms as treatment progresses. Moreover, fortifying the T- cell system appears to amplify the effectiveness of antidepressant medications, potentially resulting in a more robust recovery for patients [19]. These findings suggest that IL-2 and other cytokines may be closely related to the onset pattern and duration of depression.

IL-6: IL-6 is a highly prevalent inflammatory factor that plays an extremely important role in both central and peripheral immunity. The IL-6 family consists of ten distinct ligands and nine receptors, featuring well-known members such as IL-6, Interleukin-11(IL-11), and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF). Other key components include leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OSM), cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), cardiotrophin-like cytokine (CLC), and Interleukin-27(IL-27), along with several additional signaling molecules. These individuals all adhere to a uniform anatomical structure and communicate through similar signaling processes [20]. Research in the medical field has noted a strong link between the levels of IL-6 and feelings of depression; for instance, a study conducted in China revealed that as depression becomes more severe, the concentrations of both IL-6 and TNF-α in the blood escalate and correspondingly, so does the level of depression[21]. Older patients dealing with depression typically exhibit higher IL-6 levels when compared to those without the condition [22-24]. Furthermore, the amount of IL-6 in patients with depression tends to correlate with the status and intensity of their depressive episodes [25]. Mendelian randomization studies have confirmed a causal relationship between IL-6 and major depressive disorder [26]. Additionally, IL-6 levels are correlated with specific symptoms, such as decreased appetite and sleep disturbances, and may be exacerbated by stress [27-36]. Moreover, research has linked IL-6 levels to the intensity of depressive symptoms in teenagers, hinting that this inflammatory marker could serve as a valuable indicator for spotting early-stage major depression in young people [37].These findings emphasize the key role of IL-6 in the dynamic process of depression. In summary, clinical studies indicate that elevated IL-6 levels are positively correlated with depression severity, suggesting its potential as a biomarker. This provides an important basis for the diagnosis and prognostic assessment of depression.

IL-17A: Recent clinical studies have increasingly revealed the significant role of IL-17A in major depressive disorder (MDD) and related psychological disorders. A study on patients with acute ischemic stroke found that elevated IL-17A levels showed a strong association with the progression of anxiety and cognitive impairment. Higher IL-17A levels correlated with more severe anxiety and cognitive impairment, suggesting that serum IL 17A may serve as a potential biomarker for assessing post-stroke psychological and cognitive disorders [38]. Additionally, IL-17A has been proposed as a marker for treatment-resistant MDD, supporting its relevance in clinical assessments of treatment resistance [39]. Collectively, these clinical studies indicate that elevated IL-17A levels are closely associated with depression and psychological cognitive disorders, highlighting its potential as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker.

TNF-α: TNF-α, a key inflammatory cytokine secreted by macrophages and monocytes during acute inflammatory responses, plays a pivotal role in triggering cellular signaling pathways that ultimately result in either programmed cell death (apoptosis) or tissue necrosis. This potent molecule serves as a critical mediator in the body’s immune defense mechanisms. It is also involved in physiological sleep regulation. Multiple clinical studies have shown that serum TNF-α levels in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) are significantly higher than those in controls [40-45]. A study in antidepressant- naiveMDD patients found that TNF-α and IL-1β concentrations were markedly elevated and positively linked to Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) scores, while IL-8 levels were decreased and associated with lower HAMD and anxiety scores, suggesting a linear correlation of TNF-α with depression severity and comorbid anxiety [46]. Moreover, elevated baseline plasma TNF-α levels may predict the potential for improvement in suicidal ideation [47]. Childhood trauma in adolescents with depression often appears to correlate with increased levels of the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α. This correlation could potentially explain the variability in cytokine levels observed among these young individuals suffering from depression. Understanding this link might ultimately pave the way for more tailored and effective treatment plans for teenagers battling depression [48]. Research additionally indicates that TNF-α serum concentrations positively associate with depressive symptoms [49]. Nonetheless, research suggests a lack of correlation between TNF-α concentrations and the extent of MDD, suggesting that TNF-α may be more suitable as a diagnostic biomarker rather than an indicator of disease severity. In summary, clinical studies demonstrate that elevated TNF-α levels are closely related to MDD and have diagnostic value as a potential biomarker, although its relationship with disease severity requires further exploration.

Inflammatory Mechanisms of Depression: From Pathophysiological Insights to Therapeutic Targets

Stress-induced Peripheral Inflammation and its Transmission to the CNS: Animal studies have revealed the biological basis of inflammatory factors in depression. Long-term stress paradigms in animal studies including unpredictable chronic stress, repeated social defeat, and prolonged physical restraint—consistently trigger elevated concentrations of neuroinflammatory markers like IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF- α within cerebral tissues [50]. The establishment of animal models of depression mainly includes the despair model and the learned helplessness model. In these models, animals exhibit a lower intention to escape when exposed to uncontrollable and unpredictable aversive stimuli. The levels of catecholamines are the primary indicators, and these models have high predictive validity [51]. In a recent study in mice, persistent stress led to elevated levels of IL-6 in plasma, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus [52]. In the same study, chronic stress was also found to elevate IL-17A levels in the plasma, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus [52], and elevate TNF-α levels in the plasma, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus, correlating with inflammatory and behavioral responses [52]. This reveals the mechanisms by which these cytokines contribute to depressive-like behaviors. TNF-α has demonstrated its ability to enhance blood-brain barrier permeability (BBB) [53-55], which is associated with the emergence of depressive-like behaviors [56], providing direct evidence for how peripheral inflammation affects the central nervous system.

Cellular and Signaling Pathway Mechanisms of Inflammatory Factors within the CNS: Additionally, danger signals, inducers of inflammatory responses, can also elevate these cytokines via inflammasomes or toll like receptors (TLRs) [17]. In experiments with adult male rats, researchers observed changes in the discharge of neurons in the basolateral amygdala and found that these inflammatory mechanisms caused by the above - mentioned factors are directly associated with depressive like behaviors [9]. Current research has revealed the role of IL-6 derived from microglia promotes depressive-like behaviors by inducing astrocyte apoptosis [57]. In a mouse model of psoriasis-associated depression, IL-17A was shown to induce depressive-like symptoms via activation of the NF-κB and p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase ( p38MAPK ) signaling pathways, highlighting its key role in linking inflammation to depressive behaviors [58]. Additionally, exogenous TNF-α administration increases sleep, while TNF-α inhibition reduces spontaneous sleep, indicating its dual role in sleep regulation and depressive like behaviors. Moreover, TNF-α mRNA in the brain is produced in a circadian rhythm, with peak levels occurring during the high-sleep period [59].

Immune Dysregulation and its Protective Intervention Mechanisms in Depression: Animal model studies have provided important mechanistic support for the role of IL-2 in depression. In a rodent model exhibiting depressive symptoms triggered by prolonged stress, IL-2 has been shown to alleviate depressive-like behaviors [60]. Emerging research has shown that small amounts of IL-2 can alleviate symptoms resembling depression and counteract harmful physiological shifts by bringing the IL-6 and Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β) levels back into equilibrium, while also rebalancing the T helper 17 and Regulatory T cell (Th17 and Treg cell) populations [61].Though direct pharmacological evidence for IL-2 in depression treatment is still limited, its potential as a therapeutic agent, suggested by both clinical and animal studies, deserves attention. Future research may investigate the possibility of IL-2 as a treatment target or predictor, based on its levels in MDD patients’ serum [60], and its role in balancing immunity in mouse models [61]. Also, the lower IL-2 levels in patients with rapidly occurring, short-duration depression hint at its potential for guiding personalized treatment strategies.

Pharmacological Evidence of Existing Antidepressants acting by Regulating Peripheral Inflammatory Factors: In terms of pharmacological evidence, clinical intervention studies have further verified the reversibility of the association between inflammatory factors and depression. In recent years, several clinical studies have confirmed that antidepressant treatment in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) can reduce serum IL-1β levels [62-64]. In treatment-naive MDD patients, TNF-α levels in peripheral blood significantly decreased after antidepressant treatment, even falling below those of healthy controls [65]. This finding is consistent with recent studies on duloxetine treatment and was further confirmed in a recent pharmacological study [66]. Clinical data indicate that antidepressants such as fluoxetine improve depressive symptoms by reducing serum IL-6 levels [67]. This not only supports the influence of inflammatory mediators on depression development but also indicates that modulating inflammatory pathways may be an effective strategy for antidepressant treatment.

Potential of Targeting Specific Inflammatory Pathways as Novel Antidepressant Strategies: Laboratory experiments with animal subjects have demonstrated that mice lacking the IL-6 gene appear to be immune to developing these depressive behaviors when subjected to stress, which further underscores the crucial part IL-6 plays in the biological pathways of depression within these experimental models [68-69]. Additionally, ketamine exerts its antidepressant effects by reducing brain IL-6 levels, and blocking the IL-6 receptor can produce sustained and rapid antidepressant effects [50-70]. These findings support IL-6 as a target for antidepressant treatment.Cutting-edge pharmaceutical research has revealed novel prospects for IL-17A intervention. It has been found that blocking IL-17A can prevent oxycodone induced depressive-like behaviors, reduce levels of pro inflammatory factors such as IL-6 in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and decrease oxycodone-derived physical dependence in rats, indicating that IL-17A promotes depression and allodynia by upregulating the VTA [71]. Meanwhile, IL-17A antibodies that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (such as secukinumab) have shown potential for treating opioid use disorder (OUD) and related depression [72], providing a new direction for clinical applications. In summary, pharmacological evidence suggests that targeting IL 17A has significant antidepressant and anti-dependence potential.

INFLAMMATORY PATHWAYS REGULATION OF DEPRESSION AND THE

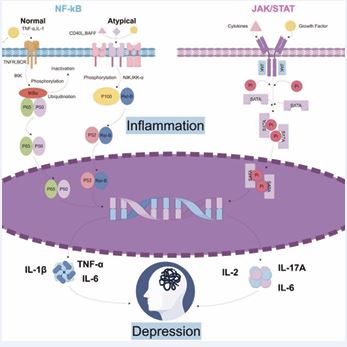

NF-κB or Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3(STAT3)-activating cytokines like IL-6 reciprocally stimulate both STAT3 and NF-κB pathways.

NF-κB

The NF-κB signaling pathway encompasses both the classic and non-classic branches. The standard NF-κB route responds to multiple triggers, enabling swift yet ephemeral gene expression and regulating the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory genes, thus acting as a key mediator of inflammatory responses. Meanwhile, activation of the non canonical NF-κB pathway occurs through a few members of the Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) receptor superfamily. Since activation of this pathway involves protein synthesis, the kinetics of non-canonical NF-κB activation are slow but sustained, consistent with its biological functions in the development of immune cells and lymphoid organs, immune homeostasis, and immune responses. Canonical and non-canonical NF-κB pathway activation requires precise regulation, underscoring ubiquitination’s critical function in these processes [73]. NF-κB can impair the function and expression of glucocorticoid receptors, leading to uncontrolled inflammatory responses, which may further exacerbate depressive symptoms [74]. The NF-κB–(IκB kinase)IKK NF-κB signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in modulating neuronal structure and function. This molecular cascade is not only involved in but also directly responsible for triggering behaviors in mice that mirror anxiety and depression, such as social withdrawal and the inability to experience pleasure [75,76]. Neurotrophic factors and glutamate represent brain-specific NF-κB activators [77,78], and this transcription factor is closely related to neuronal function neural adaptability in cognitive physiology [79,80]. Compared with controls, men with depression show enhanced NF-κB DNA binding in white blood cells following a stressful social event [81]. Conclusively, the results underscore the critical involvement of IκB Kinase (IKK) and NF-κB in mood disorders’ progression and the prospect of neural and synaptic restructuring. NF-κB signaling and IL-1β activation under stress suppress hippocampal neurogenesis and induce depressive behaviors in chronic mild stress (CMS) [82]. IL-17A may additionally stimulate NF-κB-activating receptors in certain cells [83], potentially contributing to depressive pathology in psoriatic arthritis patients. The NF-κB pathway regulates the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in vivo [84,85]. In depressive mouse models, lower hippocampal neurogenesis is linked to elevated levels of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, with the IKK/nuclear factor κB pathway mediating the effect [86].

JAK/STAT

Janus kinases (JAKs) mediate phosphorylation of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs). Post dimerization, the proteins migrate across the nuclear envelope and into the nucleus, thereby modulating the activation of pertinent genetic sequences. This pathway is referred to as the JAK/STAT (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling cascade. The cytokine-activated signaling route, also known as the IL-6 pathway, has been identified as a newly discovered cytokine- stimulated pathway. This signaling pathway plays a crucial role in numerous vital biological mechanisms, influencing key cellular activities such as growth, specialization, programmed cell death, immune system modulation, and blood cell formation. Its multifaceted nature allows it to regulate diverse physiological functions throughout the body [87]. Research on depression using rodent models has shown that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α play a role in impairing hippocampal neurogenesis. These effects are mediated, at least in part, through the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, which influences cellular communication and gene expression [88]. Researchers have found that downregulating the JAK2/STAT3 pathway can inhibit abnormal activation of microglia and improve neuroinflammatory damage [89]. Research via cellular studies validates the decrease in JAK2/STAT3 phosphorylation levels can reduce the secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β by lipopolysaccharide-induced microglia [90]. IL-1β activates JAK2/STAT3 by binding to the IL-1β receptor on the cell surface, triggering a T-cell immune response [91]. Additionally, experimental results have shown that under IL-6 induction, CD4+ T lymphocytes differentiate into Th17 cells via JAK2/STAT3 regulation [92]. Subsequently, JAK2/STAT3 binds to the IL-17 gene to enhance its transcription and lead to further secretion of inflammatory factors. Activation of the JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway can alleviate amyloid-beta-induced hippocampal neuronal damage in rats [93]. Activation of the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway can also provide some protection to neural cells in brain tissue during traumatic injury [94] (Figure 2).

Emerging research continues to underscore the critical involvement of the JAK- STAT signaling pathway in mediating the link between neuroinflammation and depressive disorders. Investigations into traditional Chinese medicinal compounds— including luteolin [95], and gastrodin [96], have demonstrated their efficacy in alleviating depression-like symptoms in murine models, with their therapeutic effects attributed to the modulation of JAK/STAT signaling. Similarly, ethyl propionate (EP) has shown promise in mitigating depressive behaviors, potentially through its interaction with the SIRT1/STAT pathway [97]. Furthermore, transcriptomic profiling in a post-stroke depression mouse model revealed that therapeutic targeting of the JAK-STAT cascade significantly reduced the manifestation of depressive symptoms [98].

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the intricate and multilayered interplay between depression and inflammatory mediators represents a pivotal frontier in understanding the pathophysiology of depressive disorders. From an expert perspective, this review highlights that core inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and the IL 1β, IL-17a, inflammasome are not merely bystanders but active regulators of the neuroimmune environment and neurotransmitter systems. Their roles extend beyond peripheral inflammation, profoundly influencing central nervous system homeostasis and contributing to the manifestation and progression of depressive symptoms. Though current research has extensively uncovered the close relationship between the pathogenesis of depression and inflammatory responses, the precise mechanisms of action of inflammatory factors remain to be fully elucidated. This complexity arises from the multifaceted roles of inflammatory factors in depression, which encompass neuroinflammation, neuroplasticity, and neurotransmitter metabolism. While some studies have begun to unravel potential mechanisms, the exact functions of inflammatory factors in the development and progression of depression are still not well defined. For instance, certain inflammatory factors (such as IL-6) may exhibit dual pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects depending on the context, and their precise roles in depression require further investigation. Additionally, systematic research on specific inflammatory factors (such as IL-17, IL-23) remains inadequate. Although recent studies have indicated that significant activation of the IL-23/Th17 axis in patients with major depressive disorder may render it a potential therapeutic target [99], the number of related studies is limited and lacks sufficient clinical validation. Balancing diverse research perspectives, it is evident that while inflammation contributes significantly to depression, it is not the sole driver. The heterogeneity of depressive disorders necessitates a nuanced approach that integrates inflammatory biomarkers with genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors. This complexity calls for a paradigm shift from a one-size-fits-all model to precision psychiatry. Advanced multi-omics technologies, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, combined with machine learning algorithms, offer unprecedented opportunities to dissect the molecular signatures of inflammation-related depression. Such integrative approaches can identify patient subgroups with distinct inflammatory profiles, enabling personalized interventions that target specific inflammatory pathways. In summary, the evolving understanding of the role of inflammatory mediators in depression underscores a transformative shift in both research and clinical management. By integrating molecular insights with cutting-edge technologies and a systems biology perspective, the field is poised to advance toward individualized, mechanism-based therapies. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration and rigorous clinical validation will be essential to translate these scientific advances into tangible benefits for patients suffering from inflammation-associated depressive disorders. This review thus not only consolidates current knowledge but also charts a forward-looking roadmap for future investigations and therapeutic innovation in the complex nexus of depression and neuroinflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by college students entrepreneurship training program (101322025061), Science and Technology Program of the Joint Fund of Scientific Research for the Public Hospitals of Inner Mongolia Academy of Medical Sciences (2023GLLH0149).

REFERENCES

- Jackson NA, Jabbi MM. Integrating biobehavioral information to predict mood disorder suicide risk. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2022; 24: 100495.

- Dawidowski B, Górniak A, Podwalski P, Lebiecka Z, Misiak B, Samochowiec J. The Role of Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia. J Clin Med. 2021; 10: 3849.

- Pesti I, Barczánfalvi G, Dulka K, Kata D, Farkas E, Gulya K. Bafilomycin 1A Affects p62/SQSTM1 Autophagy Marker Protein Level and Autophagosome Puncta Formation Oppositely under Various Inflammatory Conditions in Cultured Rat Microglial Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25: 8265.

- Hassamal S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: an overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti- inflammatories. Front Psychiatry. 2023; 14: 1130989.

- Kim KY, Shin KY, Chang KA. Potential Inflammatory Biomarkers for Major Depressive Disorder Related to Suicidal Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24: 13907.

- Pignon B, Wiernik E, Ranque B, Robineau O, Carrat F, Severi G, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and the risk of depressive symptoms: a retrospective longitudinal study from the population-based CONSTANCES cohort. Psychol Med. 2024; 54: 1-10.

- Chen Y, Xia X, Zhou Z, Yuan M, Peng Y, Liu Y, et al. Interleukin-6 is correlated with amygdala volume and depression severity in adolescents and young adults with first-episode major depressive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. 2024; 18: 773-782.

- Liu JJ, Wei YB, Strawbridge R, Bao Y, Chang S, Shi L, et al. Peripheral cytokine levels and response to antidepressant treatment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020; 25: 339-350.

- Munshi S, Rosenkranz JA. Effects of Peripheral Immune Challenge on In Vivo Firing of Basolateral Amygdala Neurons in Adult Male Rats. Neuroscience. 2018; 390: 174-186.

- Thomas AJ, Davis S, Morris C, Jackson E, Harrison R, O’Brien JT. Increase in interleukin-1beta in late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005; 162: 175-177.

- Cox EQ, Stuebe A, Pearson B, Grewen K, Rubinow D, Meltzer-BrodyS. Oxytocin and HPA stress axis reactivity in postpartum women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015; 55: 164-172.

- Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, de Andrade NQ, Liu CS, Fernandes BS, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017; 135: 373-387.

- Do?an Y, Onat A, Kaya H, Ayhan E, Can G. Depressive symptoms in a general population: associations with obesity, inflammation, and blood pressure. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011; 2011: 740957.

- Das R, Emon MPZ, Shahriar M, Nahar Z, Islam SMA, Bhuiyan MA, et al. Higher levels of serum IL-1β and TNF-α are associated with an increased probability of major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2021; 295: 113568.

- Bialek K, Czarny P, Watala C, Synowiec E, Wigner P, Bijak M, et al. Preliminary Study of the Impact of Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms of IL-1α, IL-1β and TNF-α Genes on the Occurrence, Severity and Treatment Effectiveness of the Major Depressive Disorder. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020; 40: 1049-1056.

- Ye M, Ji F, Huang C, Li F, Zhang C, Zhang Y, et al. A novel probiotic formula, BLLL, ameliorates chronic stress-induced depression-like behaviors in mice by reducing neuroinflammation and increasing neurotrophic factors. Front Pharmacol. 2024; 15: 1398292.

- Sehgal ANA, Tauber PA, Stieger RB, Kratzer B, Pickl WF. The T-Cell Growth Factor Interleukin-2, Which Is Occasionally Targeted by Autoantibodies, Qualifies as Drug for the Treatment of Allergy, Autoimmunity, and Cancer: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum (CIA) Update 2024. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2024; 185: 286-300.

- Buspavanich P, Adli M, Himmerich H, Berger M, Busche M, Schlattmann P, et al. Faster speed of onset of the depressive episode is associated with lower cytokine serum levels (IL-2, -4, -6, -10, TNF-α and IFN-γ) in patients with major depression. J PSYCHIATR RES. 2021; 141: 287-292.

- Poletti S, Zanardi R, Mandelli A, Aggio V, Finardi A, Lorenzi C, et al. Low-dose interleukin 2 antidepressant potentiation in unipolar and bipolar depression: Safety, efficacy, and immunological biomarkers. Brain Behav Immun. 2024; 118: 52-68.

- Weitz HT, Ettich J, Rafii P, Wittich C, Schultz L, Frank NC, et al. Interleukin-11 receptor is an alternative α-receptor for interleukin-6 and the chimeric cytokine IC7. FEBS J. 2025; 292: 523-536.

- Harsanyi S, Kupcova I, Danisovic L, Klein M. Selected Biomarkers ofDepression: What Are the Effects of Cytokines and Inflammation? Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 24: 578.

- Alexopoulos GS, Morimoto SS. The inflammation hypothesis in geriatric depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011; 26:1109-1118.

- Rollè L, Giordano M, Santoniccolo F, Trombetta T. Prenatal Attachment and Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17: 2644.

- Primo de Carvalho Alves L, Sica da Rocha N. Different cytokine patterns associate with melancholia severity among inpatients with major depressive disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020; 10: 2045125320937921.

- Tao H, Chen X, Zhou H, Fu J, Yu Q, Liu Y. Changes of Serum Melatonin, Interleukin-6, Homocysteine, and Complement C3 and C4 Levels in Patients with Depression. Front Psychol. 2020; 11: 1271.

- Perry BI, Upthegrove R, Kappelmann N, Jones PB, Burgess S, Khandaker GM. Associations of immunological proteins/traits with schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder: A bi- directional two-sample mendelian randomization study. Brain Behav Immun. 2021; 97: 176-185.

- Kang S, Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. Targeting Interleukin-6 Signaling in Clinic. Immunity. 2019; 50: 1007-1023.

- Ting EY, Yang AC, Tsai SJ. Role of Interleukin-6 in Depressive Disorder.Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21: 2194.

- Hoertel N, Sánchez-Rico M, Gulbins E, Kornhuber J, Carpinteiro A, Abellán M, et al. Association between FIASMA psychotropic medications and reduced risk of intubation or death in individuals with psychiatric disorders hospitalized for severe COVID-19: an observational multicenter study. Transl Psychiatry. 2022; 12: 90.

- Frank P, Jokela M, Batty GD, Cadar D, Steptoe A, Kivimäki M. Association Between Systemic Inflammation and Individual Symptoms of Depression: A Pooled Analysis of 15 Population-Based Cohort Studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2021; 178: 1107-1118.

- Milaneschi Y, Kappelmann N, Ye Z, Lamers F, Moser S, Jones PB, et al. Association of inflammation with depression and anxiety: evidence for symptom-specificity and potential causality from UK Biobank and NESDA cohorts. Mol Psychiatry. 2021; 26: 7393-7402.

- Alshehri T, Boone S, de Mutsert R, Penninx B, Rosendaal F, le Cessie S, et al. The association between overall and abdominal adiposity and depressive mood: A cross-sectional analysis in 6459 participants. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019; 110: 104429.

- Simmons WK, Burrows K, Avery JA, Kerr KL, Taylor A, Bodurka J, et al. Appetite changes reveal depression subgroups with distinct endocrine, metabolic, and immune states. Mol Psychiatry. 2020; 25: 1457-1468.

- Milaneschi Y, Lamers F, Bot M, Drent ML, Penninx BW. Leptin Dysregulation Is Specifically Associated With Major Depression With Atypical Features: Evidence for a Mechanism Connecting Obesity and Depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2017; 81: 807-814.

- Lamers F, Milaneschi Y, de Jonge P, Giltay EJ, Penninx BWJH. Metabolic and inflammatory markers: associations with individual depressive symptoms. Psychol Med. 2018; 48: 1102-1110.

- Kautz MM, Coe CL, McArthur BA, Mac Giollabhui N, Ellman LM, Abramson LY, et al. Longitudinal changes of inflammatory biomarkers moderate the relationship between recent stressful life events and prospective symptoms of depression in a diverse sample of urban adolescents. Brain Behav Immun. 2020; 86: 43-52.

- Chen Y, Xia X, Zhou Z, Yuan M, Peng Y, Liu Y, et al. Interleukin-6 is correlated with amygdala volume and depression severity in

adolescents and young adults with first-episode major depressive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. 2024; 18: 773-782.

- Wang C, Huo H, Li J, Zhang W, Liu C, Jin B, et al. The longitudinal changes of serum JKAP and IL-17A, and their linkage with anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022; 36: e24762.

- Nothdurfter C, Milenkovic VM, Sarubin N, Hilbert S, Manook A, Weigl J, et al. The cytokine IL-17A as a marker of treatment resistance in major depressive disorder? Eur J Neurosci. 2021; 53: 172-182.

- Kakeda S, Watanabe K, Nguyen H, Katsuki A, Sugimoto K, Igata N, et al. An independent component analysis reveals brain structural networks related to TNF-α in drug-naïve, first-episode major depressive disorder: a source-based morphometric study. Transl Psychiatry. 2020; 10: 187.

- Nayem J, Sarker R, Roknuzzaman ASM, Qusar MMAS, Raihan SZ, Islam MR, et al. Altered serum TNF-α and MCP-4 levels are associated with the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder: A case-control study results. PLoS One. 2023; 18: e0294288.

- Delery EC, Edwards S. Neuropeptide and cytokine regulation of pain in the context of substance use disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2020; 174: 108153.

- Delery EC, Edwards S. Neuropeptide and cytokine regulation of pain in the context of substance use disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2020; 174: 108153.

- Yao L, Pan L, Qian M, Sun W, Gu C, Chen L, et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Variations in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder Before and After Antidepressant Treatment. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11: 518837

- Liu W, Yuan J, Wu Y, Xu L, Wang X, Meng J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for major depressive disorder in undergraduate students: Dose- response effect, inflammatory markers and BDNF. Psychiatry Res. 2024; 331: 115671.

- Zou W, Feng R, Yang Y. Changes in the serum levels of inflammatory cytokines in antidepressant drug-naïve patients with major depression. PLoS One. 2018; 13: e0197267.

- Choi KW, Jang EH, Kim AY, Kim H, Park MJ, Byun S, et al. Predictive inflammatory biomarkers for change in suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder and panic disorder: A 12-week follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res. 2021; 133: 73-81.

- Rengasamy M, Marsland A, McClain L, Kovats T, Walko T, Pan L, et al. Linking childhood trauma and cytokine levels in depressed adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021; 133: 105398.

- Tsuboi H, Sakakibara H, Minamida-Urata Y, Tsujiguchi H, Hara A, Suzuki K, et al. Serum TNFα and IL-17A levels may predict increased depressive symptoms: findings from the Shika Study cohort project in Japan. Biopsychosoc Med. 2024; 18: 20.

- Ye M, Ji F, Huang C, Li F, Zhang C, Zhang Y, et al. A novel probiotic formula, BLLL, ameliorates chronic stress-induced depression-like behaviors in mice by reducing neuroinflammation and increasing neurotrophic factors. Front Pharmacol. 2024; 15: 1398292.

- Hao Y, Ge H, Sun M, Gao Y. Selecting an Appropriate Animal Model of Depression. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20: 4827.

- Medina-Rodriguez EM, Rice KC, Jope RS, Beurel E. Comparison of inflammatory and behavioral responses to chronic stress in female and male mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2022; 106: 180-197.

- Diaz A, Woo Y, Martin-Jimenez C, Merino P, Torre E, Yepes M. Tissue- type plasminogen activator induces TNF-α-mediated preconditioning of the blood-brain barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022; 42: 667- 682.

- Villalba N, Ma Y, Gahan SA, Joly-Amado A, Spence S, Yang X, et al. Lung infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces neuroinflammation and blood–brain barrier dysfunction in mice. J. Neuroinflammation. 2023; 20: 127.

- Salehpour F, Farajdokht F, Cassano P, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Erfani M, Hamblin MR, et al. Near-infrared photobiomodulation combined with coenzyme Q10 for depression in a mouse model of restraint stress: reduction in oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis. Brain Res Bull. 2019; 144: 213-222.

- Alzarea SI, Alhassan HH, Alzarea AI, Al-Oanzi ZH, Afzal M. Antidepressant-like Effects of Renin Inhibitor Aliskiren in an Inflammatory Mouse Model of Depression. Brain Sci. 2022; 12: 655.

- Shen SY, Liang LF, Shi TL, Shen ZQ, Yin SY, Zhang JR, et al. Microglia- Derived Interleukin-6 Triggers Astrocyte Apoptosis in the Hippocampus and Mediates Depression-Like Behavior. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025; 12: e2412556.

- Fabrazzo M, Cipolla S, Signoriello S, Camerlengo A, Calabrese G, Giordano GM, et al. A systematic review on shared biological mechanisms of depression and anxiety in comorbidity with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur Psychiatry. 2021; 64: e71.

- Zhang Y, Suo X, Wang X, Xu J, Xu W, Pan L, et al. Intrinsic Links Between Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Sleep Quality and Cytokines: A Network Analysis Based on Chinese Adolescents with Depressive Disorders. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2025; 18: 1033-1047.

- Harsanyi S, Kupcova I, Danisovic L, Klein M. Selected Biomarkers of Depression: What Are the Effects of Cytokines and Inflammation? Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 24: 578.

- Huang C, Zhang F, Li P, Song C. Low-Dose IL-2 Attenuated Depression- like Behaviors and Pathological Changes through Restoring the Balances between IL-6 and TGF-β and between Th17 and Treg in a Chronic Stress-Induced Mouse Model of Depression. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23: 13856.

- Hussein Kadhem Al-Hakeim, Ahmed Jasim Twayej, Arafat Hussein Al- Dujaili. Reduction in serum IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 levels and Beck Depression Inventory-II score by combined sertraline and ketoprofen administration in major depressive disorder: A clinical trial. Neurol Psychiat Br. 2018; 30: 148-153.

- Shi S, Zhang S, Kong L. Effects of Treatment with Probiotics on Cognitive Function and Regulatory Role of Cortisol and IL-1β in Adolescent Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Life (Basel). 2023; 13: 1829.

- Jiang ZM, Wang FF, Zhao YY, Lu LF, Jiang XY, Huang TQ, et al. Hypericum perforatum L. attenuates depression by regulating Akkermansia muciniphila, tryptophan metabolism and NFκB-NLRP2- Caspase1-IL1β pathway. Phytomedicine. 2024; 132: 155847.

- Chen L, Zeng X, Zhou S, Gu Z, Pan J. Correlation Between Serum High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein, Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha, Serum Interleukin-6 and White Matter Integrity Before and After the Treatment of Drug-Naïve Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Front Neurosci. 2022; 16: 948637.

- Suzuki E, Sueki A, Takahashi H, Ishigooka J, Nishimura K. Association between TNF-α & IL-6 level changes and remission from depression with duloxetine treatment. Int J Neurosci. 2024; 1-6.

- Gavril R, Dobrin PR, Pînzariu AC, Moscalu M, Grigore RG, Iacob VT, et al. Predictive Value of Inflammatory Biomarkers in Assessing Major Depression in Adults. Biomedicines. 2024; 12: 2501.

- Chourbaji S, Urani A, Inta I, Sanchis-Segura C, Brandwein C, Zink M, et al. IL-6 knockout mice exhibit resistance to stress-induced development of depression-like behaviors. Neurobiol Dis. 2006; 23: 587-594.

- Shen SY, Liang LF, Shi TL, Shen ZQ, Yin SY, Zhang JR, et al. Microglia- Derived Interleukin-6 Triggers Astrocyte Apoptosis in the Hippocampus and Mediates Depression-Like Behavior. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2025; 12: e2412556.

- Sun T, Chen Q, Mei J, Li Y. Associations between serum estradiol and IL-6/sIL-6R/sgp130 complex in female patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2023; 23: 742.

- Inan S, Meissler JJ, Bessho S, Wiah S, Tukel C, Eisenstein TK, et al. Blocking IL-17A prevents oxycodone-induced depression-like effects and elevation of IL-6 levels in the ventral tegmental area and reduces oxycodone-derived physical dependence in rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2024; 117: 100-111.

- Nothdurfter C, Milenkovic VM, Sarubin N, Hilbert S, Manook A, Weigl J, et al. The cytokine IL-17A as a marker of treatment resistance in major depressive disorder? Eur J Neurosci. 2021; 53: 172-182.

- Yu H, Lin L, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Hu H. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020; 5: 209.

- Liu F, Jia Y, Zhao L, Xiao LN, Cheng X, Xiao Y, et al. Escin ameliorates CUMS-induced depressive-like behavior via BDNF/TrkB/CREB and TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathways in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024; 984: 177063.

- Ménard C, Hodes GE, Russo SJ. Pathogenesis of depression: Insights from human and rodent studies. Neuroscience. 2016; 321: 138-162.

- Serrano García A, Montánchez Mateo J, Franch Pato CM, Gómez Martínez R, García Vázquez P, González Rodríguez I. Interleukin 6 and depression in patients affected by Covid-19. Med Clin (Barc). 2021; 156: 332-335.

- O’Neill LA, Kaltschmidt C. NF-kappa B: a crucial transcription factor for glial and neuronal cell function. Trends Neurosci. 1997; 20: 252- 258.

- Meffert MK, Baltimore D. Physiological functions for brain NF- kappaB. Trends Neurosci. 2005; 28: 37-43.

- O’Mahony A, Raber J, Montano M, Foehr E, Han V, Lu SM, et al. NF- kappaB/Rel regulates inhibitory and excitatory neuronal function and synaptic plasticity. Mol Cell Biol. 2006; 26: 7283-7298.

- Meffert MK, Chang JM, Wiltgen BJ, Fanselow MS, Baltimore D. NF- kappa B functions in synaptic signaling and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2003; 6: 1072-1078.

- Pace TW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, et al. Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163: 1630-1633.

- Wang L, Guo T, Guo Y, Xu Y. Asiaticoside produces an antidepressant-like effect in a chronic unpredictable mild stress model of depression in mice, involving reversion of inflammation and the PKA/pCREB/BDNF signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2020; 22: 2364-2372.

- Ngo U, Shi Y, Woodruff P, Shokat K, DeGrado W, Jo H, et al. IL-13 and IL-17A activate β1 integrin through an NF-kB/Rho kinase/PIP5K1γ pathway to enhance force transmission in airway smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024; 121: e2401251121

- Zhong Y, Liang B, Zhang X, Li J, Zeng D, Huang T, et al. NF-κB affected the serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β via activation of theMAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway in rat model of acute pulmonary microthromboembolism. Pulm Circ. 2024; 14: e12357.

- Malko P, Jia X, Wood I, Jiang LH. Piezo1 channel-mediated Ca2+ signaling inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of the NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway and generation of TNF-α and IL-6 in microglial cells. Glia. 2023; 71: 848-865.

- Eyre H, Baune BT. Neuroplastic changes in depression: a role for the immune system. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012; 37: 1397-1416.

- Lee BW, Moon SJ. Inflammatory cytokines in psoriatic arthritis: understanding pathogenesis and implications for treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24: 11662.

- Çetin EU, Beyaz?t Y. A meta-analyses on the role of IL-6 associated JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway modulation in the inflammatory bowel disease complicated colonic cancer development. Turk. J. Intern. Med. 2021; 3: 4-6.

- Zeng J, Zhao YL, Deng BW, Li XY, Xu J, Wang L, et al. [Role of JAK2/ STAT3 signaling pathway in microglia activation after hypoxic- ischemic brain damage]. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2020; 33: 190-194.

- Shrivastava K, Llovera G, Recasens M, Chertoff M, Giménez-Llort L, Gonzalez B, et al. Temporal expression of cytokines and signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 3 activation after neonatal hypoxia/ischemia in mice. Dev Neurosci. 2013; 35: 212-225.

- Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature. 2017; 541: 481-487.

- You Z, Timilshina M, Jeong BS, Chang JH. BJ-2266 ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through down- regulation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2017; 47: 1488-1500.

- Zhao F, Wang ZJ, Zhang S, Wang JJ, Zhao JY, Pei YB, et al. Effects of brain neuropeptide analog Rattin on β-amyloid-induced hippocampal neuronal damage in rats. J Neuroanat. 2019; 35: 357-364.

- Xiong Y, Zhou X, Yu C, Tong Y. Reduction of acute radiation-induced brain injury in rats by anlotinib. Neuroreport. 2024; 35: 90-97.

- Ma DF, Chen L, Zhang CX, Ren WQ. Effects of luteolin on the polarization of hippocampal microglia in rats with depression via the JAK1/STAT3 pathway. DER. 2021; 44: 2587-2594.

- Wang S, Dong WJ, Liu PL, Yang GM, Shen BY, Yu H, et al. Role of JAK2- STAT3 signaling pathway in the improvement of depressive-like behaviors in mice by gastrodin. Progress in Modern Biomedicine. 2021; 21.

- Su WJ, Hu T, Jiang CL. Cool the Inflamed Brain: A Novel Anti- inflammatory Strategy for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024; 22: 810-842.

- Wu Y, Deng J, Ma J, Chen Y, Hu N, Hao S, et al. Unraveling the Pathogenesis of Post-Stroke Depression in a Hemorrhagic Mouse Model through Frontal Lobe Circuitry and JAK-STAT Signaling. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024; 11: e2402152.

- Yuan RX, Fu YM, Yu SY. Advances in the study of the mechanisms of action of T helper 17 cells and regulatory T cells in depression. J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ Med Sci. 2021; 41: 1384-1388.