Thoracic Compliance and Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA): A

- 1. Independent researcher, Graduate in Nutrition and Food Science (Unicamillus), Psychology, and Organizational and Managerial Sciences, Italy

Abstract

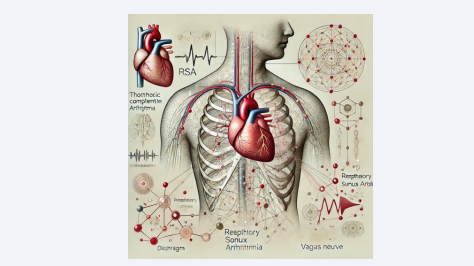

Respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) represents a rhythmic variation in heart rate synchronized with breathing, serving as a marker of autonomic regulation and psychophysical well-being. In children, RSA is particularly pronounced, reflecting greater vagal flexibility and an enhanced ability to adapt to internal and external stimuli. However, factors such as poor posture, sedentary behavior, and modern social pressures are progressively compromising thoracic compliance, interfering with diaphragmatic breathing and reducing the effectiveness of RSA.

This article explores the connection between bodily dysmorphisms, emotional regulation mediated by vagal tone, and social pressures, highlighting how these factors negatively affect physiological development and the psychophysical well-being of children. Preventive strategies and targeted interventions are proposed to promote a balance between autonomic regulation and emotional resilience, supporting healthy development within a social and evolutionary context.

CITATION

Lombardo C (2024) Thoracic Compliance and Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA): A “Secure Base” for Psychophysical Well-Being and Social Evolution. Ann Neurodegener Dis 8(1): 1038.

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA) is a natural variation in heart rate that reflects vagal tone and emotional regulation. During childhood, RSA is more pronounced, promoting greater adaptability to internal and external stimuli. This phenomenon, closely linked to the parasympathetic nervous system, has significant implications for emotional self-regulation and general well-being [1].

However, in recent decades, there has been an increase in bodily dysmorphisms, particularly in the thoracic region among children. These changes are primarily associated with prolonged sitting and the adoption of closed postures. Such alterations not only affect the musculoskeletal structure but can also interfere with diaphragmatic breathing and, consequently, the functionality of RSA.

RSA IN CHILDREN: A PHYSIOLOGICAL RHYTHM AND WELL-BEING MARKER

Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA) represents a natural variation in heart rate synchronized with the respiratory cycle: heart rate increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration. In children, RSA is more pronounced compared to adults, reflecting greater plasticity in the autonomic nervous system and higher vagal tone. This pronounced RSA is considered a marker of good physiological and psychological health, as it facilitates effective emotional regulation and balanced responses to stress [1].

According to the Polyvagal Theory proposed by Porges, vagal tone is fundamental for emotional and behavioral regulation. Elevated vagal tone, measured through RSA amplitude, is associated with improved emotional self-regulation and positive social behaviors in children. This physiological state supports the development of a secure base, a central concept in Bowlby’s Attachment Theory [2], which refers to a child’s ability to explore their environment while maintaining a sense of security derived from stable attachment relationships.

High RSA promotes a balanced physiological response to stress, allowing children to reduce emotional hyper activation and recover more quickly from stressful events. For example, a study by Geisler et al. [3], found that high heart rate variability, indicative of pronounced RSA, is positively correlated with emotional regulation and psychological well-being in children.

However, factors such as poor posture and social pressures can negatively affect RSA in children. Increased sedentary behavior and the adoption of closed postures—such as compressed thoracic cages and hunched shoulders—can reduce thoracic compliance, impair diaphragmatic breathing, and subsequently decrease RSA [4,5]. These physiological changes, in turn, can hinder emotional regulation, reducing a child’s ability to manage stress and promoting states of anxiety or emotional dysregulation [6].

In conclusion, RSA is not only an indicator of physiological health but also a crucial element for emotional regulation and psychological well-being in children. Promoting proper postural habits and environments that encourage free movement is essential to maintaining healthy RSA and fostering balanced emotional and social development.

BODILY DYSMORPHISMS AND POSTURE: A FACTOR OF INTERFERENCE WITH RSA

The impact of posture on children’s physiological and psychological health is a growing area of interest, particularly concerning Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA). Increased time spent in a seated position, often associated with prolonged use of digital devices and school-related activities, is linked to the development of bodily dysmorphisms. Among these, thoracic closure-characterized by compressed thoracic cages and hunched shoulders-is one of the most common postural alterations.

These structural changes not only compromise musculoskeletal aesthetics and functionality but also have profound implications for respiratory physiology and the regulation of the autonomic nervous system.

Causes of Thoracic Dysmorphisms and Impacts on RSA

The causes contributing to thoracic dysmorphisms and respiratory issues, with subsequent effects on Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA), can be grouped into ten main categories:

a. Postural and Mechanical Causes

Incorrect posture, such as prolonged sitting, lumbar hyperlordosis, or shoulder protraction, alters thoracic structure and limits diaphragmatic breathing. Structural deformities such as scoliosis or kyphosis further exacerbate the condition.

b. Behavioral and Social Habits

Sedentary behavior, excessive use of electronic devices, and social norms enforcing rigid postures contribute to thoracic compression. Additionally, carrying heavy school bags negatively impacts posture.

c. Muscular and Skeletal Factors

Muscle imbalances, such as overactive pectorals and weak dorsal muscles, restrict thoracic mobility and impair diaphragm function. Joint stiffness in the thoracic cage exacerbates these issues.

d. Psychological and Stress Factors

Chronic stress, emotional or physical trauma, and psychological insecurity induce closed postures that compromise breathing and increase muscle tension.

e. Environmental and Ergonomic Factors

Non-ergonomic workstations, restrictive clothing, and incorrect sleeping positions negatively affect posture and breathing efficiency.

f. Evolutionary and Genetic Factors

Congenital conditions like pectus excavatum and genetic predispositions influence the development of the thoracic cage and spinal column.

g. Medical Conditions and Pathologies

Chronic respiratory diseases, thoracic trauma, and autonomic nervous system dysfunctions impair respiratory capacity and reduce RSA.

h. Incorrect Training Styles

Unbalanced training focused on pectorals with insufficient attention to the back leads to muscle imbalances. Additionally, incorrect breathing techniques during physical exercise can impair diaphragm function.

i. Hormonal Changes and Growth Factors

Adolescence and obesity are critical periods for physical development and can contribute to postural and respiratory imbalances.

j. Lifestyle-Related Factors

Smoking, poor nutrition, and dehydration compromise muscle function and posture, limiting thoracic expansion.

Impact of Posture on Diaphragmatic Breathing and RSA

Poor posture, characterized by compressed thoracic structures and restricted breathing, directly interferes with diaphragmatic function, encouraging shallow, thoracic breathing. This type of respiration reduces the efficiency of the parasympathetic system, hindering vagal nerve function and impairing the heart rate variability associated with RSA [4].

A study by Lee et al. [7], revealed that children with poor posture exhibit significantly reduced heart rate variability compared to their peers with correct posture. Over time, this reduction can promote a physiological state of chronic stress, marked by hyper activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

EFFECTS ON HEART RATE VARIABILITY AND PSYCHOPHYSICAL WELL-BEING

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a direct measure of the efficiency of the autonomic nervous system, particularly the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. Among its primary components, respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) is considered a key indicator of vagal tone and the body’s capacity to adapt to external and internal stimuli. Breathing and posture play a central role in modulating HRV and, consequently, psychophysical well-being.

Breathing and Vagal Flow

Deep, diaphragmatic breathing promotes vagus nerve activation, sending signals to the brain to induce relaxation and regulate emotional responses [5]. In contrast, shallow thoracic breathing, typically seen in individuals with poor posture such as a compressed thoracic cage or rounded shoulders, reduces vagal signaling. This disruption in HRV is associated with a diminished ability to regulate emotions and stress.

A significant example comes from studies analyzing autonomic responses under postural stress. Wheatley et al [8], observed that thoracic breathing in individuals with rigid postures leads to a reduction in HRV, increasing the risk of physiological states marked by sympathetic hyper activation.

Open Posture and Parasympathetic Activation

Proper posture, characterized by an expanded thoracic cage and natural spinal alignment, facilitates deep breathing and parasympathetic system activation. This type of posture is associated with increased RSA, which enhances adaptive responses to stress. A study by Nair et al. [9], demonstrated that children with open and dynamic postures exhibit higher HRV, indicative of greater emotional resilience and regulatory capacity.

Closed Posture and Emotional Dysregulation

Conversely, a closed posture, characterized by thoracic compression and forward-curved shoulders, reduces the efficiency of diaphragmatic breathing. This compromises vagal tone, resulting in low HRV, which is linked to anxiety states and emotional dysregulation [6]. This condition can create a vicious cycle: closed posture fosters shallow breathing, which in turn exacerbates physiological and emotional stress.

Implications for Psychophysical Well-Being

The reduction in HRV, caused by poor posture or inefficient breathing, negatively affects overall well-being:

- Emotional: Low HRV is associated with a reduced ability to manage complex emotions and an increased risk of anxiety and depression [3].

- Physiological: Sympathetic hyper activation can lead to higher incidences of cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and chronic fatigue.

- Social: Compromised vagal tone reduces adaptability in social interactions, negatively affecting behavior and empathy.

SOCIAL PRESSURES AND POSTURE

Social norms and behavioral expectations imposed on children from an early age play a crucial role in shaping their postural habits. One of the key expectations is maintaining a “proper” seated position during school hours or in formal settings, which often involves rigid and unnatural postures. While these norms are intended to promote discipline and focus, their long-term side effects include significant postural alterations and potential impacts on psychophysical well-being.

Physiological Impacts of Prolonged Sedentary Posture

Children spend an average of 6–8 hours per day in a seated position, whether at school or using digital devices. According to Park et al. [10], this habit significantly increases the prevalence of bodily dysmorphisms such as rounded shoulders, thoracic kyphosis, and compression of the thoracic cage. These structural changes compromise thoracic compliance, limit diaphragmatic breathing, and hinder proper vagus nerve function, which is closely tied to the regulation of Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA).

A study by Claus et al. [11], demonstrated that children with closed or rigid postures show reduced heart rate variability, indicative of a diminished capacity for autonomic regulation and an increased predisposition to chronic stress. Over time, these physiological changes may impair children’s ability to effectively manage emotional and social stimuli.

Psychological Consequences of Social Pressures

In addition to physical effects, social expectations of maintaining an “appropriate” posture also impact emotional well-being. Children forced into rigid positions often develop greater behavioral rigidity, which can translate into reduced emotional and cognitive flexibility [8].

The relationship between posture and emotional state was further explored by Nair et al. [9], who found that rigid posture correlates with reduced heart rate variability and increased cortisol levels, the hormone associated with stress. Moreover, the emphasis on maintaining an “ideal” posture in social and school settings may create social anxiety in children who feel constantly observed and judged. This state of constant vigilance, associated with a closed posture, fosters a cycle of physiological and psychological stress, further reducing RSA and emotional self-regulation capacity.

PREVENTIVE STRATEGIES AND INTERVENTIONS

Addressing the negative effects of social norms and poor postural habits requires an integrated approach involving schools, families, and healthcare professionals. These interventions should aim to prevent bodily dysmorphisms and enhance autonomic regulation and psychophysical well-being in children. Below are some key strategies:

a. School-based interventions

Schools play a central role in implementing preventive strategies. Modifying the school environment and the structure of children’s daily routines can significantly impact posture and RSA:

- Active Breaks during Lessons: Introducing short sessions of physical activity or stretching during the school day helps reduce postural rigidity. Recent studies, such as Claus et al. [11], highlight that 5-10 minutes of active breaks improve spinal mobility and promote deeper, more regular breathing.

- Ergonomic Seating: Using desks and chairs designed to support the natural posture of the body can prevent thoracic cage compression and promote functional breathing. Flexible solutions, such as height-adjustable desks or dynamic chairs, are particularly effective [12].

- Promotion of Physical Activity: Incorporating school programs with sports and games that encourage thoracic expansion and active movement can counteract the effects of prolonged sedentary behavior.

b. Postural education

Educational interventions are essential to teach children the importance of a natural and dynamic posture:

- Body Awareness: Specific programs combining body awareness exercises, such as the Alexander Technique or yoga, can help children identify and correct poor posture. According to Wheatley & Wilkins [8], these approaches improve the ability to perceive bodily tension and promote optimal alignment.

- Parental and Teacher Involvement: Educating the adults surrounding children is crucial for ensuring consistent support. Workshops for parents and teachers can provide practical tools to help children maintain correct posture.

c. Relaxation techniques

Integrating techniques aimed at relaxation and autonomic regulation can reduce the effects of postural stress on respiratory physiology and RSA:

- Respiratory Biofeedback: This technique uses devices to monitor breathing and heart rate, providing visual feedback that helps children improve their autonomic regulation. Lehrer & Gevirtz [5], emphasize that biofeedback is particularly useful for increasing heart rate variability and promoting relaxation.

- Guided Diaphragmatic Breathing: Training children to use the diaphragm during breathing enhances lung expansion and stimulates the vagus nerve. Studies by Vaschillo et al. [13], demonstrate that this technique positively impacts emotional regulation.

- Integrated relaxation techniques: Approaches such as mindfulness and progressive muscle relaxation can reduce stress associated with postural rigidity, indirectly improving posture itself.

SOCIAL RULES, SELF-REGULATION, AND EVOLUTIONARY PRESSURES

Social rules and behavioral norms established from early childhood profoundly influence children’s behavior and physical development. Among these, maintaining a “proper” posture, often required during extended periods of study or participation in school activities, proves to be a significant source of pressure. While these norms aim to promote discipline and focus, their long- term side effects can have significant consequences, particularly on physiological self-regulation and psychophysical health.

Reduced free movement and impact on RSA

Prolonged maintenance of rigid postures limits free movement, a fundamental element for proper muscular, skeletal, and physiological development. According to Wheatley & Wilkins [8], spontaneous physical activity in children is essential to maintaining adequate thoracic compliance and stimulating diaphragmatic breathing. The absence of continuous movement, however, contributes to postural restrictions that reduce thoracic expansion and compromise vagus nerve function, directly tied to Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA).

A study by Bornstein et al. [14], demonstrated that children who spend more time engaging in free movement exhibit significantly higher RSA compared to those confined to static postures for extended periods. This suggests that social norms imposing static behavior may interfere with autonomic regulation, increasing vulnerability to stress.

The Link between RSA and Emotional Regulation

RSA is considered a direct indicator of the capacity for emotional self-regulation, influencing how children respond to stressful stimuli. Low RSA has been associated with reduced emotional control and avoidance behaviors, as highlighted by Beauchaine [6]. Social pressures promoting postural rigidity and conformity limit freedom of movement and, consequently, hinder emotional development.

Furthermore, adopting rigid social norms can increase the risk of anxiety and emotional dysregulation, especially in more sensitive children. A study conducted by Nair et al. [9], found that closed and static postures correlate with increased cortisol levels, the stress hormone, underscoring the link between posture, reduced RSA, and emotional dysregulation.

EVOLUTIONARY PRESSURES AND SOCIAL ADAPTATION

From an evolutionary perspective, free movement and postural flexibility have been essential for survival and adaptation. However, modern social pressures tend to suppress these natural characteristics, promoting rigid and static behaviors. According to Porges [1], emotional and social adaptability depends strongly on vagus nerve function, which regulates RSA. Norms limiting movement not only reduce the efficiency of the autonomic nervous system but can also negatively affect the development of social skills such as empathy and communication.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PSYCHOPHYSICAL WELL- BEING

The interference of social rules in children’s postural and autonomic development has significant implications:

- Increased Risk of Anxiety Disorders: Reduced RSA has been linked to greater emotional vulnerability and difficulty in managing stressful social situations [6].

- Compromised Physical Well-Being: Rigid posture reduces diaphragmatic breathing capacity, increasing physical and mental stress [5].

- Challenges in Self-Regulation: Low RSA limits a child’s ability to self-regulate emotionally, compromising psychological and social development.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Understanding the connection between bodily dysmorphisms, RSA, and emotional regulation can open new avenues for preventive and therapeutic interventions. Programs incorporating respiratory biofeedback combined with targeted postural exercises could help children improve diaphragmatic breathing and, consequently, vagal tone.

Furthermore, promoting school environments that encourage greater physical activity and reduce sedentary periods could prevent bodily dysmorphisms while supporting the development of a healthy and resilient autonomic nervous system.

CONCLUSIONS

Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA) represents a key marker of psychophysical well-being, highlighting the link between autonomic nervous system physiology, emotional regulation, and environmental and social influences. In children, elevated RSA indicates vagal flexibility and adaptability, but this function can be compromised by factors such as poor posture, social pressures, and norms limiting free movement.

Practical Implications

The evidence presented suggests that bodily dysmorphisms and rigid social norms negatively influence RSA, limiting children’s capacity to self-regulate emotionally and respond to stressful stimuli in a balanced manner. Closed posture and reduced diaphragmatic breathing compromise vagus nerve function, fostering chronic physiological stress and emotional dysregulation. Moreover, modern social pressures, such as maintaining static and “proper” positions, negatively affect both physical and psychological development, increasing the risk of anxiety, emotional difficulties, and stress-related disorders.

Recommendations and Future Directions

To preserve and enhance RSA in children, it is essential to adopt integrated strategies involving schools, families, and health professionals. Preventive and corrective interventions include:

- Postural exercises and diaphragmatic breathing techniques that stimulate vagal function and reduce stress-related effects.

- Active breaks and dynamic school environments to promote free movement and prevent sedentary behavior.

- Biofeedback and mindfulness, useful for improving autonomic regulation and developing body and emotional awareness skills.

Additionally, increased education on posture and raising awareness among teachers and parents can help create an environment that supports healthy and resilient development. It is crucial to rethink the social rules governing children’s behavior, fostering a balance between discipline, free movement, and psychophysical well-being.

In conclusion, the interaction between RSA, bodily dysmorphisms, and social norms offers a multidimensional perspective on child health, underscoring the need for targeted and personalized interventions. Promoting practices that support functional breathing, proper posture, and a flexible social environment can represent a significant step toward improving children’s psychophysical well-being. A healthy RSA is not only an indicator of physiological health but also a bridge to better emotional regulation, resilience, and social adaptation.

REFERENCES

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biol Psychol. 2007; 74: 116-143.

- Bowlby J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Basic Books. 1988.

- Geisler FC, Vennewald N, Kubiak T, Weber H. The impact of heart rate variability on subjective well-being is mediated by emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences 2010; 49: 723-728.

- Kapandji I A. Fisiologia articolare: Tronco e rachide. Piccin. 2008.

- Lehrer PM, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: How and why does it work? Front Psychol. 2014; 5: 756.

- Beauchaine TP. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: A transdiagnostic biomarker of emotion dysregulation and psychopathology. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015; 3: 43-47.

- Lee J, Han D, Shin J. Postural alterations and their association with autonomic nervous system activity in children. J Pedia Rehab Med 2018; 11: 225-234.

- Wheatley CM, Wilkins BW. The role of thoracic posture in autonomic regulation and cardiovascular health. Autonom Neurosci Basic Clin. 2020; 227: 102689.

- Nair S, Purohit S, Kumar R. Posture and psychological stress: Exploring the connection in children. Int J Behav Develop. 2020; 44: 335-345.

- Park J, Kim Y, Lee J. The impact of sedentary behavior on posture and cardiovascular function in children: A review. J Physic Act Health. 2019; 16: 401-409.

- Claus AP, Hides JA, Moseley GL. Posture and movement: Concepts for understanding their role in pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021; 125: 448-456.

- Dianat I, Karimi MA. Effects of ergonomic desk and chair intervention on musculoskeletal outcomes in children. Applied Ergonomics. 2020; 85: 103065.

- Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Lehrer PM. Characteristics of resonant breathing. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2017; 42: 227-237.

- Bornstein DB, Beets MW. Movement behaviors and their associations with biomarkers of cardio metabolic health. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2019; 51: 1303-1311.