An eye-movement study on motion inference

- 1. School of Public Administration, Northwest University, China

- 2. Psychology Section, Secondary Sanatorium of Air Force Healthcare Center for Special Services, China

- 3. Unit 94922 of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, China

- 4. Department of Psychiatry, Dalian Rehabilitation and Nursing Center, China

- 5. Unit 94865 of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, China

ABSTRACT

Background: In motion extrapolation, there are two distinct eye movements during the invisible motion period, namely, smooth pursuit and saccade, and it has been proposed that the saccade compensates for the slowing of smooth pursuit.

Methods: 30 undergraduate students from Xi’an, China were recruited to participate in the experiment based on motion inference task. the onset time of the saccade after target occlusion after target occlusion and the accuracy of motion duration estimation under conditions of different contrast levels of the moving targets were compared. Eyelink 1000 plus was used to collect the eye movement data.

Results: For the fast and slow moving targets, the onset time of the saccades under low contrast condition was significantly longer than that under high contrast condition while for medium-moving target, there was no significant difference. There was no significant difference in the accuracy of motion duration estimation, regardless of the target contrast and velocity.

Conclusions: Anticipatory saccade may be not triggered by smooth pursuit attenuation errors accumulation, and the smooth pursuit after occlusion may have a higher accuracy than the anticipatory saccade. The present study highlights to the underlying mechanism of motion extrapolation, and provides new ideas for the application of eye movement technology in the motion extrapolation test.

KEYWORDS

- Motion extrapolation

- Anticipatory saccade

- Smooth pursuit

- Eye movement

CITATION

Zhang F, Xu T, Lu J, Hu M, Liu Y, et al. (2024) An Eye-Movement Study on Motion Inference. Ann Psychiatry Ment Health 12(2): 1193.

INTRODUCTION

Neural transmission takes time, so for the localization of moving objects such as catching of a football shot at the goal, shooting at moving targets and estimation of aircraft landing, position information available in visual cortical areas will be outdated [1,2]. Besides, delay also occurs in the formulation, transmission and execution of motor commands [3]. There should be a significant influence of this delay on movement misjudgment [4]. Motion misjudgment refers to the delay in time when an individual responds by using representations to make judgments about the motion of an object in the absence of conditions that preclude vision [5]. However, we can always accurately track moving objects and intercept or avoid them at the right time and location [6]. A widely accepted explanation for how our brain breaks up the limit set by physical delays is motion extrapolation [7,8]. Among other things, motion inference is the process that enables one to track a moving object and make predictions about its location when that object cannot be seen. The motion extrapolation theory proposes that the brain can constantly extrapolate the trajectory of a moving object to accurately predict its current position [9]. In fact, the reception of information from receptors, neural conduction and information processing take time, so that the information we are aware of is actually outdated to an extent equivalent to the total delay of these processes. Thus in motor inference tasks, the brain uses past information to predict the present rather than presenting past information directly. For example, Nijhawan demonstrated through the flash-lag illusion that visual perception involves the process of making inferences from available information [5]. Luca et al., found in their study of masked motion that subjects do not simply respond when a target is reproduced but tend to predict its reproduction [10]. Philippa et al., argued that the high Phi illusion is a consequence of the early mechanisms of motion inference in the visual system [11]. These studies have demonstrated that our brain can utilize its own mechanisms to effectively compensate for delays and predict future events [12,13]. However, these delays may be irrelevant for the manipulation of static objects. Whereas, they are critical for moving objects, especially in occupations that require high motion sensitivity, such as pilots and athletes [14]. The research on motion extrapolation mechanism is of great significance to meet the requirements in the selection and training of these occupations.

It has been proved that overlapped systems guide eye movements and motion extrapolation [3,15,16]. Firstly, the premotor theory of attention points out that the oculomotor system mediates the shift of visual spatial attention [17]. As a task of using visual spatial attention, motion extrapolation inevitably interacts with oculomotor control system, and it has been proven that the frontoparietal attentional system may controls both eye movements and motion extrapolation [18]. Secondly, significant difference has been revealed in motion extrapolation under fixation condition with free eye movement condition [19], interestingly, even under the condition of fixation, the moving direction of the occluded target caused small changes of the eye position around the fixation in the same direction as the moving target [15]. Finally, motion extrapolation and eye movements may share a common neural basis. Previous study suggested that frontal eye fields (FEF) might perform a crucial function in the internal representation when estimating an invisible target trajectory [20], the neurons of medial superior temporal area (MST) have been found activated during the occluded target period [21], and the left mediotemporal area (hMT/ V5+) was activated when participants were asked to imagine the invisible target [22]. Meanwhile the relationship between these brain regions and eye movement has been confirmed by many studies [23-27]. The study of eye movement process of motion extrapolation may help reveal the cognitive processing mechanism because of their close connections.

A typical experimental paradigm for motor extrapolation is the production task, in which subjects are asked to observe a moving target that becomes invisible or disappears after a period of time, and subjects press a button when they judge that the moving target has reached its destination [28]. Kinematic analyses of eye movements in production tasks [29,30], show that the target begins to move with a catch-up saccade, and then the eye smoothly tracks the moving target until the target is occluded. During the initial phase when the target is occluded, the eye smoothly tracks the moving target; however, the smooth pursuit then diminishes [31]. Finally, the anticipatory saccade returns to bring the eye to its destination. It has been shown that motor extrapolation is driven by information from two sources [32], intraretinal input and extraretinal input. Intraretinal input can be used during visible motion periods, but in the absence of visual feedback signals during invisible motion periods, extraretinal input is primarily used [33], which consists of cognitive factors, including target appearance expectations and internal cognitive representations [34], and relies heavily on intraretinal input [35]. In conditions without visual feedback and with only extra- retinal input, there are two distinct eye movement processes, smooth following decay and anticipatory saccades. In conditions without visual feedback and with only extra-retinal inputs, there are two distinct eye movement processes, namely smooth following decay and anticipation of saccades [36]. Smooth following typically occurs when tracking a smoothly moving target in the visual environment, and it helps to keep the image of the moving target near the retinal fovea [37-39]. However, when the target disappears behind an occluder, individuals have the ability to continue smooth following for about 200 ms [40], although to some extent this ability cannot be used at will in the absence of visual stimuli [41]. When an effect can be predicted to occur, a saccade to the location of the expected effect may occur before the effect actually occurs, and this saccade is defined as an anticipatory saccade [42]. According to Orban de Xivry et al., anticipatory saccades can compensate for the attenuation of smooth following [43]. Furthermore, Park et al., argued that deficits in anticipatory saccades degrade predictive performance and that better smooth following in patients with autism spectrum disorders is a byproduct of deficits in anticipatory saccades [44]. And this smooth pursuit motion inevitably leads to a lag of eye movement position relative to the moving target, and is accompanied by a certain amount of attenuated cumulative error. For example, when the moving target is occluded, smooth pursuit is attenuated and anticipatory saccades point to the destination the target will reach [45,46]. During the visible phase, the moving target has higher contrast and is more favorable to extra-retinal inputs, so errors accumulate relatively slowly. If the hypothesis that smooth-following decay error accumulation triggers expected saccades holds, then expected saccades for moving targets with higher contrast should occur later than for moving targets with lower contrast. Therefore, the accumulation of smooth-following decay errors may not trigger the expected saccade back. Therefore, Is the anticipatory saccade triggered by the errors accumulation during the smooth pursuit attenuation? It remains to be further examined.

Interestingly, related studies have shown that contrast plays an important role in smoothing follow-through decay and subsequent anticipatory saccades. For example, the accuracy of motion perception in motion extrapolation is compromised in low-contrast conditions [47-49]. Alexis et al., varied the motion extrapolation task masking distance and target contrast to obtain different masking times, and found that the errors in estimated times were similar if the masking times were the same regardless of target contrast and masking distance [50]. A more recent study also found that motion-inferred time estimates were less accurate and had greater variability in low-contrast conditions compared to high-contrast conditions [51]. An earlier study found similar results in that eye movements were more accurately located in the high contrast condition. This suggests that the ability of a smooth tracking system to accurately track a target may increase with increasing contrast [52]. That is, low- contrast conditions during the visible motion phase result in a weaker residual visual signal after motion occlusion. Therefore, this study set up moving targets with different contrasts to obtain residual visual signals of different intensities to investigate whether smooth-following attenuation triggers anticipatory saccades. Our research hypothesis was that if expected saccades are triggered by smooth-following attenuation, then expected saccades should occur earlier for low-contrast moving targets because weak residual visual signal inputs may accumulate ground errors earlier.

In summary, the present study constructed moving targets of different contrast levels in the visible motion stage to obtain different error accumulation rates in the smooth pursuit attenuation stage after occlusion. We compared the onset times of anticipatory saccade under different error accumulation rate conditions to verify whether the accumulation of smooth pursuit attenuation errors could trigger the anticipatory saccade. In addition, we also compared the accuracy of motion time estimation under different contrast conditions. The present study is of great significance in enriching the theory of motion extrapolation, and provides suggestions for application of eye movement technology in the occupation selection and training of motion extrapolation ability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 30 undergraduate students (aged 20.03 ± 0.87) from Xi’an, China were recruited to participate in the experiment. The recruitment criteria of the participants were male, right-handed, normal vision or corrected-to-normal vision, no amblyopia and astigmatism, no history of sensory, perceptual or motor disorders, and no experience of participating in similar experiments. All participates signed their consent before the experiment, and the study was carried out in accordance with the 1991 Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethics Committee of the Xijing Hospital of the Air Force Military Medical University (No. KY20224106-1).

Apparatus

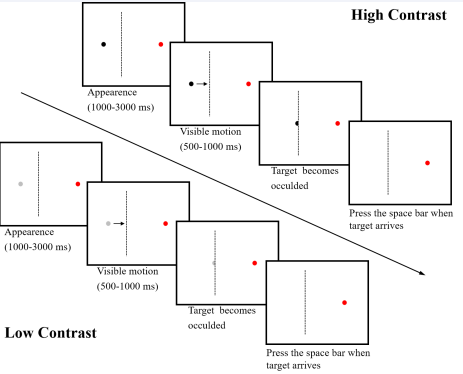

The visual stimuli were presented on the Dell p1917s display with a refresh rate of 60Hz. The eye movement data was collected by Eyelink 1000 plus, and the head rest was fixed 65cm away from the screen. Experiment Builder 2.2.61 was used to develop experimental programs based on the production task of motion extrapolation. As shown in Figure 1, the diameters of the moving target and the destination point were set to 1.54cm, they were in the same horizontal direction with a distance of 18.75cm.

Figure 1 Production task of motion extrapolation. Note: Upper panels: High contrast of the moving target. Lower panels: Low contrast of the moving target. Third panels: “target occlusion ”?the occlusion edge indicated by the dotted line is not visible in the actual tests.

In Experiment Builder, the color data type consists of 4 integer numbers between 0 and 255, representing the red, green, blue and transparency values. The background color of the screen was set to white (255, 255, 255, 255), the color of the destination point was set to red (255, 0, 0, 255). The color of the moving target was set to black with two kinds of contrast levels (0, 0, 0, 255 for the high contrast level and 204, 204, 204, 50 for the low contrast level). After 1000ms, 1500ms, 2000ms, 2500ms or 3000ms, the target moved horizontally to the right at a constant velocity (slow 4.69cm/s, medium 6.25cm/s, fast 9.38cm/s). After a movement of 4.69 cm, the target is occluded. But after closure, there is no longer a target, i.e., the target has neither position nor velocity. Subjects needed to note that the target reappeared later at another eccentric location as if its velocity remained constant. We informed participants that the stationary target and the moving target were the same target, and that they only needed to press the spacebar when they estimated that the moving target had reached the end point.

Experiment Design

Within-subjects design with single factor was adopted in present study. The independent variable was the contrast level of the moving target (high, low). Dependent variables were as follows: (1) Onset time of anticipatory saccade (OTAS) after target occlusion, anticipatory saccade was defined according to a combined threshold of velocity (30°/s), acceleration (8000°/s2) and motion (0.1°) [43]; (2) The absolute value of the difference between the actual arrival time of the moving target and the time of key pressing, namely absolute error deviation of time (ADT), ADT reflected the estimation accuracy of motion duration.

Procedure

The first stage is practice test. The camera of Eyelink was focused to obtain the sharpest image of the participant’s eyes. The thresholds of pupil and corneal reflection (CR) were set to effectively distinguish eyes from other areas in the image. Mapping the centers of the pupil and the CR helped estimation of gaze direction [44]. Then systematic calibration and validation were performed to determine the correspondence between pupil- CR position in the camera image and gaze position on the display screen. After that, the test began, each trial with the combination of different target contrast levels and velocities was presented for 5 times, and a total of 30 trials are presented randomly. The second stage is the formal test. Each trial with the combination of different target contrast levels and velocities was presented for 20 times, and a total of 120 trials are presented randomly. Other procedures were the same as the practice test.

Statistical Analysis

Data Viewer 4.2.1 was used to package and export time and position information of the eye movements and keys. SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used for the sample distribution of OTAS and ADT indices. For the data that fit a normal distribution, the Student’ t-test for paired comparison was used to test the significance of difference of OTAS and ADT indices under different contrast conditions. When the data did not exhibit a normal distribution, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. For the above statistical analyses, the significance level was taken as α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Difference of OTAS indices under different contrast conditions

We used a 2 (contrast: low, high) × 3 (speed: slow, medium, fast) repeated measures ANOVA. The findings revealed a significant main effect of contrast, F (1,30) = 11.709, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.288. Therefore, further analysis using post hoc multiple comparisons revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between low and high contrast in the slow speed condition (172 ± 60 versus 156 ± 67 ms for the low and high contrast conditions, p < 0.05). no statistically significant difference between low and high contrast in the medium speed condition (179 ± 54 versus 169 ± 72 ms for the low and high contrast conditions, p = 0.198); in the fast speed condition, there was a statistically significant difference between low contrast and high contrast (179 ± 54 versus 169 ± 72 ms for the low contrast and high contrast condition, respectively, p < 0.01). The main effect of speed was significant, F (1.658,30) = 3.399, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.105. Similarly, further analysis using post-hoc multiple comparisons revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between the speed conditions, either in the low- contrast or high-contrast conditions (p > 0.05). In contrast, the interaction between contrast and speed was not significant, F (2,30) = 0.584, p = 0.561, η2 = 0.020. Figure 2 shows the results of the significance test for the differences in the OTAS indices across contrast conditions.

Figure 2 Difference of OTAS indices between the high and low contrast conditions. Note: For the slow and fast targets, the OTAS indices were significantly different between the low and contrast conditions (p-values = 0.016 and 0.002). For the medium speed target, the difference did not reach statistical significance (p-value=0.198). Each panel shows the mean ± S.D values (n = 30 subjects); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Difference of ADT indices under different contrast conditions

The results of the significance tests of difference of ADT indices under different contrast conditions are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Difference of ADT indices between the high and low contrast conditions. Note: For the slow, medium-speeded and fast targets, the ADT indices were not significantly different between the low and contrast conditions (p-values = 0.167, 0.306 and 0.697). Each panel shows the mean ± S.D values (n = 30 subjects); * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.”

We used a 2 (contrast: low, high) × 3 (speed: slow, medium, fast) repeated measures ANOVA. The findings showed that the main effect of contrast was not significant, F (1,30) = 0.663, p = 0.422, η2 = 0.022. the main effect of speed was significant, F(1.176,30) = 51.180, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.638. Thus, further analysis using post hoc multiple comparisons revealed that the low contrast condition showed a statistically significant difference between slow, medium, and fast speed two-by-two comparisons all showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.001). Similarly, statistically significant differences were found between slow, medium, and fast speeds in the high-contrast condition (p < 0.001). In contrast, the interaction between contrast and speed was not significant, F (2,30) = 0.478, p = 0.622, η2 = 0.16.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between the smooth pursuit and the anticipatory saccade in motion extrapolation and provide suggestions for the use of eye movement technology in the test of motion extrapolation ability. To this end, we compared the OTASs and ADTs of the moving targets with different contrast levels.

Anticipatory saccade may be not triggered by smooth pursuit attenuation errors accumulation

In our study, for both the fast- and slow-moving targets, the saccades occurred significantly earlier with the high contrast target than with the low contrast target. For the medium-speeded target, the trend of earlier saccades when the target was high- contrast did not reach statistical significance. A smooth pursuit eye movement is usually made in response to a target moving

slowly in the visual field, stabilizing its image on the retina [37- 39]. However, when an event is expected to occur and before it does individuals may experience a saccade to the expected effector location, which is defined as an anticipatory saccade [40]. In locomotor extrapolation, when a moving target is occluded, smooth following is attenuated and anticipatory saccades are directed toward the destination the target will reach [41,42]. This may be indicative of the fact that during the visible phase, visual signals take longer to decay for high-contrast targets than for low-contrast targets. Thus from a neurophysiological point of view, high-contrast targets decay the visual signal slower than low-contrast targets after target occlusion. Interestingly, we found this result to be the opposite of our research hypothesis that chasing a low-contrast target recruits more neurons than chasing a high-contrast target, and that the decay of activity depends on the number of active neurons: its duration increases with the number of neurons.

Smooth pursuit may have a higher accuracy than anticipatory saccade

There was no significant difference in the accuracy of motion duration estimation between the high and low contrast targets, suggesting that extending smooth pursuit under the condition with low contrast level may be beneficial for maintaining accuracy of motion time estimation. Bennett and Barnes [53], suggested that participants produced anticipatory saccade to compensate the errors in eye position caused by the attenuation of smooth pursuit. However, according to Battaglini and Ghiani [16], smooth pursuit is of great significance in motion extrapolation. For example, it ensures that one can track a moving object and predict its position when it is not visible through the individual’s spatial visualization ability, automatically tracking the target trajectory and thus estimating the duration of the invisible target’s motion. In addition, In addition, Kerzel et al. have also suggested that under low-contrast target conditions, when individuals need to infer the motion and spatial location of objects, and when they need to track many targets that cannot be attended to at the same time, accurate smoothing of the pursuit of hidden targets is beneficial to fulfill the requirement of ensuring the acquisition of high-precision spatial information and accurately predicting the reappearance of targets [54]. Presumably, under the more difficult condition, such as tracking a low contrast moving target, in order to maintain the motion estimation accuracy, individuals are more likely to use highly accurate strategy. That said, they require more attention, which in turn requires the release of more neuronal resources to accomplish the task, which in turn leads to estimating that the duration of the invisible target’s movement will be a little longer. Therefore, there may be a higher accuracy in smooth pursuit than anticipatory saccade after occlusion. As suggested by Horner et al. [55], although the accuracy of motion duration estimation is a common dependent variable in motion extrapolation studies, it does not provide a good index for a complete understanding of the motion extrapolation process. In summary, given the possible limitations of traditional accuracy metrics (i.e., reaction time, correctness, correctness per unit of time), the present study wanted to provide a new eye movement metric to reflect the testing process with a view to future use in career selection and training.

The underlying strategies for smooth tracking and anticipatory saccade

There are two strategies that explain why we can make accurate estimates in estimating the motion duration of invisible targets. The first strategy is the timing strategy. According to this strategy, individuals use the necessary information about visible motion to estimate the duration of motion after occlusion and count down [30,56], and this strategy is only effective when the target is moving at a constant speed. The second strategy is called tracking strategy. This strategy emphasizes tracking by the individual through the use of visual or covert attention, and the individual continues to track the moving target occlusion target as accurately as possible when the moving target is not visible [57,58]. Previous studies have shown that both strategies are involved in estimating the motion duration of an occluded target [56,59]. This is inconsistent with our findings, which found that for fast-moving and slow-moving targets, saccades occurred significantly earlier for high-contrast targets than for low- contrast targets. For medium-speed targets, on the other hand, the tendency for earlier saccades to occur when the target was high-contrast did not reach statistical significance. This finding suggests that in estimating the duration of motion of a stealthy target, the saccade landed at the moving target destination before the arrival of the target, then the subjects maintained their gaze toward the target destination and counted down the motion duration [15,60]. Timing strategies play a role in this process. For example, the results of Lyon et al.’s experiments showed that if the experimental paradigm allowed for a simple timing strategy, subjects would use this strategy instead of attempting to track the target during the masking period, and when asked how they accomplished the task, subjects claimed to be tracking the location of the masked target until the end point, and that this timing mechanism was unconscious [61].

CONCLUSION

Our present study compared the onset times of anticipatory saccades of moving targets with different contrast levels and verified that anticipatory saccade may be not triggered by smooth pursuit attenuation errors accumulation. Based on the lack of significant difference in the accuracy of motion duration estimation between different contrast levels, we concluded that the smooth pursuit after occlusion may have a higher accuracy than the anticipatory saccade. The present study is of great significance in enriching the theory of motion extrapolation, and provides new ideas for the application of eye movement technology in the career selection of motion extrapolation ability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z., T.XX.; methodology, F.Z., T.X.; software, M.H., J.L.; validation, Y.L., S.Z.; formal analysis, Y.T., H.C.; investigation, F.Z., T.XX., H.C.; resources, F.Z.; data curation, F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, F.Z., T.XX.; writing—review and editing, J.L., S.Z., Y.T.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, T.X.; project administration, M.H., T.XX.; funding acquisition, F.Z., T.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Technical Plan of Military Logistics Scientific Research Project, Grant No. CKJWS221L001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Xijing Hospital (KY20224106-1).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the datasets involve unfinished research projects. If necessary, requests to access the datasets should contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the individuals who participated in the study. We also thank all the administrative staff and teachers in the university who help us with the recruitment.

REFERENCES

- De Valois RL, De Valois KK. Vernier acuity with stationary moving Gabors. Vision Res. 1991; 31: 1619-1626.

- Schmolesky MT, Wang Y, Hanes DP, Thompson KG, Leutgeb S, Schall JD, et al. Signal timing across the macaque visual system. J Neurophysiol. 1998; 79: 3272-3278.

- van Heusden E, Rolfs M, Cavanagh P, Hogendoorn H. Motion Extrapolation for Eye Movements Predicts Perceived Motion-Induced Position Shifts. J Neurosci. 2018; 38: 8243-8250.

- Yook J, Lee L, Vossel S, Weidner R, Hogendoorn H. Motion extrapolation in the flash-lag effect depends on perceived, rather than physical speed. Vision Res. 2022; 193: 107978.

- Nijhawan, Romi. Motion extrapolation in catching. Nature. 1994; 370: 256-257.

- Smeets JB, Brenner E, Lussanet M. Visuomotor delays when hitting running spiders. In Advances in perception-action coupling, Paris: EDK.1998; 36-40.

- Borghuis BG, Leonardo A. The Role of Motion Extrapolation in Amphibian Prey Capture. J Neurosci. 2015; 35: 15430-15441.

- Hogendoorn H. Motion extrapolation in visual processing: Lessons from 25 years of flashlag debate. The J Neurosci. 2020; 40: 5698-5705.

- Nijhawan R, Wu S. Compensating time delays with neural predictions: are predictions sensory or motor?. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2009; 367: 1063-1078.

- Luca B, Clara C. Contribution of Visuospatial and Motion-Tracking to Invisible Motion. Frontiers in Psychol. 2016; 7: 1369.

- Johnson P, Davies S, Hogendoorn H. Motion extrapolation in the High- Phi illusion: Analogous but dissociable effects on perceived position and perceived motion. J Vis. 2020; 20: 8.

- Mischiati M, Lin HT, Herold P, Imler E, Olberg R, Leonardo A. Internal models direct dragonfly interception steering. Nature. 2015; 517: 333-338.

- Hogendoorn H, Burkitt AN. Predictive coding of visual object position ahead of moving objects revealed by time-resolved EEG decoding. Neuroimage. 2018; 171: 55-61.

- Guan LC. A method for prediction the trajectory of table tennis in multirotation state based on binocular vision. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022; 2022: 8274202.

- Makin AD, Poliakoff E. Do common systems control eye movements and motion extrapolation? Q J EXP PSYCHOL. 2011; 64: 1327-1343.

- Battaglini L, Ghiani A. Motion behind occluder: Amodal perception and visual motion extrapolation. Visual Cognition. 2021; 1: 1-25.

- Rizzolatti G, Riggio, Sheliga BM. Space and selective attention. In C. Umila` & M. Moscovitch (Eds.), Attention and performance: XV. Conscious and nonconscious information processing Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2012; 231-265.

- Makin AD, Poliakoff E, Ackerley R, El-Deredy W. Covert tracking: a combined ERP and fixational eye movement study. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e384797.

- Bennett SJ, Benguigui N. Is acceleration used for ocular pursuit and spatial estimation during prediction motion? PLoS One. 2013; 8: e63382.

- Barborica A, Ferrera VP. Estimating invisible target speed from neuronal activity in monkey frontal eye field. Nature Neurosci. 2003; 6: 66-74.

- Ilg UJ, Thier P. Visual tracking neurons in primate area MST are activated by smooth-pursuit eye movements of an “imaginary” target. J Neurophysiol. 2003; 90: 1489-1502.

- Kaas A, Weigelt S, Roebroeck A, Kohler A, Muckli L. Imagery of a moving object: the role of occipital cortex and human MT/ V5+. Neuroimage. 2010; 49: 794-804.

- Kimura Y, Enatsu R, Yokoyama R, Suzuki H, Sasagawa A, Hirano T, et al. Eye Movement Network Originating from Frontal Eye Field: Electric Cortical Stimulation and Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2021; 61: 219-227.

- Cameron IG, Riddle JM, D’Esposito M. Dissociable Roles of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex and Frontal Eye Fields during Saccadic Eye Movements. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015; 9: 613.

- Kurkin S, Akao T, Shichinohe N, Fukushima J, Fukushima K. Neuronal activity in medial superior temporal area (MST) during memory- based smooth pursuit eye movements in monkeys. Exp Brain Res. 2011; 214: 293-301.

- Manning TS, Britten KH. Retinal Stabilization Reveals Limited Influence of Extraretinal Signals on Heading Tuning in the Medial Superior Temporal Area. J Neurosci. 2019; 39: 8064-8078.

- De Sá Teixeira NA, Bosco G, Delle Monache S, Lacquaniti F. The role of cortical areas hMT/V5+ and TPJ on the magnitude of representational momentum and representational gravity: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Exp Brain Res. 2019; 237: 3375-3390.

- Tresilian JR. Perceptual and cognitive processes in time-to-contact estimation: analysis of prediction-motion and relative judgment tasks. Percept Psychophys. 1995; 57: 231-245.

- Zheng R, Maraj BKV. The effect of concurrent hand movement on estimated time to contact in a prediction motion task. Exp Brain Res. 2018; 236: 1953-1962.

- Benguigui N, Bennett SJ. Ocular pursuit and the estimation of time-to- contact with accelerating objects in prediction motion are controlled independently based on first-order estimates. Exp Brain Res. 2010; 202: 327-339.

- Bennett SJ, Benguigui N. Is acceleration used for ocular pursuit and spatial estimation during prediction motion?. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e63382.

- Collins CJ, Barnes GR. The occluded onset pursuit paradigm: prolonging anticipatory smooth pursuit in the absence of visual feedback. Exp Brain Res. 2006; 175: 11-20.

- Bosco G, Monache SD, Gravano S, Indovina I, Maffei V, Zago M, et al. Filling gaps in visual motion for target capture. Front Integr Neurosci. 2015; 9: 13.

- Chen T, Ding J, Yue GH, Liu H, Li J, Jiang C. Global-local consistency benefits memory-guided tracking of a moving target. Brain Behav. 2022; 12: e2444.

- Bennett SJ, Baures R, Hecht H, Benguigui N. Eye movements influence estimation of time-to-contact in prediction motion. Exp Brain Res. 2010; 206: 399-407.

- Madelain L, Krauzlis RJ. Effects of learning on smooth pursuit during transient disappearance of a visual target. J Neurophysiol. 2003; 90: 972-982.

- Miyamoto T, Miura K, Kizuka T, Ono S. Properties of smooth pursuit adaptation induced by theta motion. Physiol Behav. 2021; 229: 113245.

- Schröder R, Kasparbauer AM, Meyhöfer I, Steffens M, Trautner P, Ettinger U. Functional connectivity during smooth pursuit eye movements. J Neurophysiol. 2020; 124: 1839-1856.

- Ke SR, Lam J, Pai DK, Spering M. Directional asymmetries in human smooth pursuit eye movements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 4409-4421.

- Mrotek LA, Soechting JF. Predicting curvilinear target motion through an occlusion. Exp Brain Res. 2007; 178: 99-114.

- Collins CJ, Barnes GR. The occluded onset pursuit paradigm: prolonging anticipatory smooth pursuit in the absence of visual feedback. Exp Brain Res. 2006; 175: 11-20.

- Pfeuffer CU, Kiesel A, Huestegge L. A look into the future: Spontaneous anticipatory saccades reflect processes of anticipatory action control. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2016; 145: 1530-1547.

- Orban de Xivry JJ, Bennett SJ, Lefèvre P, Barnes GR. Evidence for synergy between saccades and smooth pursuit during transient target disappearance. J Neurophysiol. 2006; 95: 418-427.

- Park WJ, Schauder KB, Kwon OS, Bennetto L, Tadin D. Atypical visual motion prediction abilities in autism spectrum disorder. Clin Psychol Sci. 2021; 9: 944-960.

- Diaz G, Cooper J, Rothkopf C, Hayhoe M. Saccades to future ball location reveal memory-based prediction in a virtual-reality interception task. J Vis. 2013; 13: 20.

- Bennett SJ, Barnes GR. Timing the anticipatory recovery in smooth ocular pursuit during the transient disappearance of a visual target. Exp Brain Res. 2005; 163: 198-203

- de’Sperati C, Thornton IM. Motion prediction at low contrast. Vision Res. 2019; 154: 85-96.

- Hecht H, Brendel E, Wessels M, Bernhard C. Estimating time-to- contact when vision is impaired. Sci Rep. 2021; 11: 21213.

- Ni R, Kang JJ, Andersen GJ. Age-related declines in car following performance under simulated fog conditions. Accid Anal Prev. 2010; 42: 818-826.

- Alexis D.J. Makin,Ellen Poliakoff. Do common systems control eye movements and motion extrapolation? The Quarterly J Experimental Psychol. 2011; 64: 1327-1343.

- Wang H, Zhao J, Wang H, Hu C, Peng J, Yue S, et al. Attention and Prediction-Guided Motion Detection for Low-Contrast Small Moving Targets. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2023; 53: 6340-6352.

- Delicato LS, Derrington AM. Coherent motion perception fails at low contrast. Vision Res. 2005; 45 (17): 2310-2320.

- Bennett SJ, Barnes GR. Timing the anticipatory recovery in smooth ocular pursuit during the transient disappearance of a visual target. Exp Brain Res. 2005; 163: 198-203.

- Kerzel D, Jordan JS, Müsseler J. The role of perception in the mislocalization of the final position of a moving target. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2001; 27: 829-840.

- Horner CA, Schroeder JE, Mitroff SR, Cain MS. The effect of extended target concealment on motion extrapolation. J Vision. 2019; 19: 12.

- DeLucia PR, Liddell GW. Cognitive motion extrapolation and cognitive clocking in prediction motion task. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1998; 24: 901-914.

- Battaglini L, Casco C. Contribution of Visuospatial and Motion- Tracking to Invisible Motion. Front Psychol. 2016; 7:1369.

- Makin AD, Chauhan T. Memory-guided tracking through physical space and feature space. J Vis. 2014; 14: 10.

- Miyamoto T, Numasawa K, Hirata Y, Katoh A, Miura K, Ono S. Effects of smooth pursuit and second-order stimuli on visual motion prediction. Physiol Rep. 2021; 9: e14833.

- Miyamoto T, Numasawa K, Hirata Y, Katoh A, Miura K, Ono S. Effects of smooth pursuit and second-order stimuli on visual motion prediction. Physiol Rep. 2021; 9: e14833.

- Don R Lyon, Wayne L Waag. Time course of visual extrapolation accuracy. Acta Psychologica. 1995; 89: 239-260.