Factors Associated with HIV Testing History and HIV Seropositivity in a Large National Sample of Transgender Adults

- 1. School of Social Work, California State University–Long Beach, USA

ABSTRACT

Purpose: This paper looks at rates of HIV testing and HIV seropositivity among transgender adults. It also explores the factors associated with greater odds of having been tested for HIV and greater odds of testing positive for HIV, and investigates the presence of syndemic effects.

Methods: Data from the 2015 U.S. National Transgender Survey were used to examine the “triple whammy” relationship in a sample of 27,715 transgender Americans aged 18 or older. Odds ratios and multivariate logistic regression were used to examine the data.

Results: 51.5% of the respondents had ever been tested for HIV, and only 24% of those individuals (12.4% of the sample) had been tested during the previous year. The HIV seropositivity rate was 1.3%. Older age, higher educational attainment, and reaching various transition milestones were among the strongest predictors of lifetime HIV testing. Risk factors for being HIV-positive included gender identity (female), race (African American), age (middle-aged), and educational attainment (lower).

Conclusions: Rates of HIV testing are low among transgender adults, and among those tested, the likelihood of being HIV-positive is much greater than in the population-at-large. Certain subpopulations of transgender individuals are much more likely than others to report never having been tested for HIV and/or to say that they had tested positive for HIV. Substantial evidence was found for the presence of syndemic-type effects influencing both the likelihood of having been tested for HIV and the odds of testing HIV-positive.

KEYWORDS

- Transgender

- HIV testing

- HIV seropositivity

- Syndemic effects

CITATION

Klein H, Washington TA (2024) Factors Associated with HIV Testing History and HIV Seropositivity in a Large National Sample of Transgender Adults. Ann Psychiatry Ment Health 12(2): 1195.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, new HIV infections have reduced in number during the past several years, down from averaging 38,000–42,000 new cases per year throughout most of the 2000s to 34,000–40,000 new cases per year throughout the 2010s to approximately 28,000 new cases per year as of the 2020s (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], [1]. To help curtail the spread of HIV, researchers have teamed up with U.S. government officials to develop and periodically update a document known as the National HIV/AIDS Strategy–a compendium of recommendations of the various things that America needs to do in order to reduce the number of new HIV infections [2]. The ultimate goal of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy is to bring the number of new infections to zero. To help reach this goal, a cornerstone of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy is the promotion of HIV testing, so that as many people as possible are aware of their current HIV serostatus. This is, in fact, Goal

1.2 in the current edition of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy [2]. Additionally, recognizing that transgender persons have, for years, been experiencing much-higher-than-average rates of HIV seropositivity, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy specifically stipulates a need for HIV-related stigma reduction resources to be devoted to the transgender community (Goal 3.1.4) [2]. Moreover, the National HIV/AIDS Strategy recommends that the United States “develop new and . . . effective, evidence-based or evidence-informed interventions that address intersecting factors of HIV, homelessness or housing instability, mental health and violence, substance use, and gender especially among . . . transgender women . . .” (Goal 3.4.6) [2]. One of its specific target goals is the improvement of HIV viral suppression rates from the most-recent rate of 80.5% up to a 95% viral suppression rate (Indicator 6F) [2].

These are important, lofty, and laudable goals, particularly in light of research findings regarding HIV testing and HIV infection rates among transgender persons in general and among transgender women in particular. First, most studies have shown that HIV testing rates among transgender persons are very low. Pitasi and colleagues [3], found that lifetime HIV testing rates are low for transgender women (35.6%) and transgender men (31.6%) alike, with fewer than one-third of these individuals having been HIV tested during the preceding year (10.0% and 10.2%, respectively). Based on a study of 300 transgender adults in the United States, Rood and colleagues [4], found that 27.0% had never been tested for HIV and an additional 30.7% of the

study participants had been tested previously but not during the preceding year. In an earlier report, Pitasi et al. [3], reported that past-year HIV testing rates were particularly low among transgender women, with a prevalence rate of no more than 10%. Data published by the CDC offer a more optimistic snapshot, though, showing that 96% of transgender women report having been tested for HIV at least once during their lives and 82% report having been tested for HIV during the previous year [5]. It should be noted, however, that the findings from this study are an outlier in the published literature at this point in time.

Second, among transgender persons who have been tested for HIV, seropositivity rates have been shown to be quite high, especially among transgender women. Recent research from the CDC [6], found that 42% of the transgender women in their survey of seven American cities were HIV-infected. Baral and colleagues [7], reported that HIV infection rates among transgender women were much higher than in the population-at- large, perhaps as much as thirty-four times greater than they are among other adults aged 15-49. Hollander [8], observed that HIV seropositivity rates were five times greater among transgender women than they were among transgender men. In a study of 1,877 transgender women located in 23 cities in the United States, Pitasi and colleagues [9], reported a study-wide seropositivity rate of 4.6%. They also noted that African Americans in their sample were more than three times as likely as their Caucasian counterparts to test positive for HIV. This is consistent with Clark et al.’s [10], finding that, among transgender women, more than 80% of all new HIV diagnoses were among women of African American or LatinX descent. It is also consistent with the CDC’s [6], finding that, among transgender women, 17% of Caucasians, 35% of Latinas, and 62% of African Americans were HIV-positive.

Third, use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medication to prevent the spread of HIV is low among transgender women (with very limited information available about its use among transgender men). Based on a study of 55 African American transgender women, Eaton and colleagues [11], reported that 5.6% of their study participants were current users of PrEP, which represented 13.0% of those persons who had even heard of PrEP at the time of study participation. According to the CDC [6], 31.9% of transgender women in their seven-city study reported any past-year use of PrEP, with rates being lower among Caucasians (22.6%) than they were among African Americans (30.6%) and Latinas (36.9%).

Fourth, involvement in risky sexual behaviors is prevalent among transgender women (again, with little having been reported about transgender men). Hollander [8], attributed the higher- than-average rates of HIV seropositivity among transgender women to greater involvement in sex-trading activities, having sex with HIV-positive partners, and having sex with anonymous partners, all of which were anywhere from two to five times more common among transgender persons than among all other groups. CDC [6], data showed that 59.6% of the HIV-negative transgender women and 48.6% of the HIV-positive transgender women in their study reported engaging in condomless anal sex during the previous year.

By and large, the few studies summarized above are what is known about HIV testing among transgender persons. Practically nothing has been written about the reasons why transgender persons do not get tested for HIV, and little has been published regarding the factors associated with greater versus lesser rates of HIV testing in this population. In the present study, which is based on data from a large national sample of American transgender adults, the authors examine the factors associated with HIV testing and HIV seropositivity. This investigation focuses on the following research questions: (1) How prevalent is HIV testing among transgender adults? (2) What factors differentiate persons who have been tested for HIV from those who have never been tested for HIV? (3) Among transgender persons who have been tested for HIV, how prevalent is being HIV-positive? (4) What factors are associated with HIV seropositivity among transgender adults? Question #2 and Question #4, in particular, have important ramifications for prevention and intervention initiatives targeting HIV risk among transgender individuals.

METHODS

Data and Procedures

The data for the present research came from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS2015) [12]. Data were collected during the summer of 2015, from a total sample of 27,715 transgender persons residing anywhere in the United States or one of its territories, or who were living overseas while serving actively in the U.S. military. At the time it was undertaken, it was the largest study of its kind ever having been undertaken to understand transgender persons’ lives. Access to the survey was centralized via a single online portal/website, and all persons completed the survey online. It could be completed via any type of web-enabled device (e.g., computer, tablet, smart phone, etc.) and was available both in English and Spanish language versions.

The questionnaire collected information pertaining to a wide variety of types of harassment, discrimination, and violence that transgender persons may have experienced in a wide variety of settings, such as work, school, public restrooms, public places, governmental offices, while serving in the military, among others. The USTS2015 questionnaire contained some information pertaining to substance use and mental health functioning. It also captured information about various aspects of the transitioning process, including social aspects of transitioning (e.g, divulging information about one’s transgender identity to partners, friends, family members, coworkers, etc.), taking hormone treatments, and various surgical procedures that might be undergone to facilitate gender identity integration. Detailed demographic-type data about each respondent were also collected.

Participants were offered the opportunity to win either a $500 participation grand prize (n=1) or a $250 participation prize (n=2), chosen by random at the end of the data collection period. More than one-third (35.2%) of the eligible persons opted not to enter in the prize drawing. If they did not enter the raffle or were not one of the three prize winners chosen at random, then participation entailed receiving no other rewards/incentives/

remunerations. Extremely detailed information about the study, its content, its initial development, and its implementation may be found in James et al. (2016). The original USTS2015 study received institutional review board approval from the University of California–Los Angeles prior to implementation. The present research for the secondary analysis of the USTS2015 data received institutional review board approval from California State University–Long Beach.

Measures Used

The principal variables of interest in the present research pertained to HIV testing. Lifetime testing history was assessed via a single yes/no question asking respondents whether or not they had ever been tested for HIV. Persons who had been tested at least once before were asked the month and year of their most recent HIV test. Additionally, people who had been tested for HIV at least once before were asked about the outcome of their most recent HIV test. For the purposes of the present study, responses to the latter were dichotomized into persons who had tested positive for HIV and those who had not. In the present paper, other responses (e.g., did not return for my test results, test results were inconclusive) were excluded from that part of the analysis.

A variety of measures were examined in the bivariate analyses investigating the factors associated with having versus never having been tested for HIV. These measures included: age (two measures: one continuous measure and one dichotomous measure [constructed based on post hoc analysis of the age- and-HIV-testing-history data] comparing persons who were aged 40-59 to those who were younger or older), gender identity (dichotomous), binary versus nonbinary identity (dichotomous), educational attainment (dichotomous, at least a college education versus less education), race (two dichotomous measures: Caucasians versus persons of color, African Americans versus all others), relationship status (dichotomous, married or “involved” with someone versus not married/“involved”), overall health (self-assessed, ordinal), lives near or below the poverty line (dichotomous, yes/no), employment status (dichotomous, unemployed versus not unemployed), has health/medical insurance (yes/no), overall level of psychological distress (a six- item continuous scale measure derived from the Kessler-6 Scale [13], Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91), and number of different types of anti-transgender discrimination, harassment, and violence the person experienced (a twenty-item continuous scale measure, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76). Additionally, substance abuse/misuse during the previous month was also included as an independent variable in these analyses. This was constructed from four separate items asking about past month (1) binge drinking, (2) illegal drug use, (3) use of prescription or over-the-counter medications other than as prescribed, and (4) marijuana or hashish use for nonmedical purposes. The use of any of these four substances constituted “substance abuse/misuse” for the purposes of the present study. Finally, in other published works [14,15], the present authors determined that reaching or not reaching various transition milestones has been related to most major outcome measures and, on that basis, several transition milestones measures were included in the present analysis as well. Transition milestones refer to specific events or occurrences in transgender persons’ transitioning experiences that demarcate their lives in a “before

X happened” versus “after X happened” kind of way. These transition milestones represent different stages of progress in transgender persons’ journey toward fully accepting their gender identity and incorporating that identity more fully into their everyday lives. Each milestone, once reached or achieved, is one additional step toward living authentically and completely as a member of the gender with which the person identifies most closely. In the present study, eleven such measures–all scored dichotomously as “milestone reached” or “milestone not reached”–were included as covariates in the multivariate analysis: (1) disclosed being transgender to any family members, (2) disclosed being transgender to all family members, (3) disclosed being transgender to any friends, (4) disclosed being transgender to all friends (5) disclosed being transgender to any coworkers/classmates, (6) disclosed being transgender to all coworkers/classmates, (7) changed name and/or gender on any legal documents, (8) changed name and/or gender on all legal documents, (9) began taking gender-affirming hormones, (10) had any gender-conforming surgical procedures, and (11) had all gender-conforming surgical procedures available to persons of his/her gender.

Statistical Analysis

Due to the large sample size used in this study, throughout this paper, results are reported as being statistically significant whenever p<.01 instead of the more-commonly-used p<.05. For the first part of the analysis, examining what factors are associated with lifetime HIV testing history, odds ratios (OR) were computed with 95% confidence intervals (CI95) being reported.

For the multivariate analysis, multivariate logistic regression was used as the analytical strategy. Items found to be related (p<.01) or marginally related (p>.10>.01) to HIV testing in the bivariate analyses were entered into a multivariate equation, to determine which ones remained significant when the impact of the others was taken into account. Both a forward-selection and a backward-removal approach were used, to make sure that the results did not differ. Standardized coefficients (i.e., β values) for each covariate in the model are presented in Table 1 so that effects sizes may be compared from item to item.

Table 1: Multivariate Factors Predicting HIV Testing.

|

independent variable |

OR |

CI95 |

β |

p<|x| |

|

age |

1.04 |

1.03–1.04 |

0.25 |

.0001 |

|

race = African American |

2.56 |

2.10–3.12 |

0.09 |

.0001 |

|

educational attainment = college graduate or more |

1.77 |

1.66–1.89 |

0.15 |

.0001 |

|

relationship status = married or “involved” |

1.16 |

1.07–1.27 |

0.03 |

.0007 |

|

self-identifies as nonbinary |

1.27 |

1.18–1.37 |

0.06 |

.0001 |

|

transition milestone #2 (has told all family members that he/she is transgender) |

1.15 |

1.06–1.26 |

0.03 |

.0016 |

|

transition milestone #6 (has told all people at work or school that he/she is transgender) |

1.22 |

1.13–1.31 |

0.05 |

.0001 |

|

transition milestone #7 (has changed name and/or gender on any legal documents) |

1.22 |

1.13–1.32 |

0.05 |

.0001 |

|

transition milestone #9 (has begun taking gender-affirming hormones) |

1.50 |

1.38–1.64 |

0.11 |

.0001 |

|

transition milestone #10 (has had at least one gender-conforming surgical procedure) |

1.30 |

1.19–1.41 |

0.07 |

.0001 |

|

any substance abuse during past 30 days |

1.96 |

1.84–2.09 |

0.18 |

.0001 |

|

number of types of anti-transgender harassment, discrimination, and/or violence experienced |

1.13 |

1.12–1.14 |

0.23 |

.0001 |

|

overall level of psychological distress |

0.97 |

0.96–0.98 |

0.10 |

.0001 |

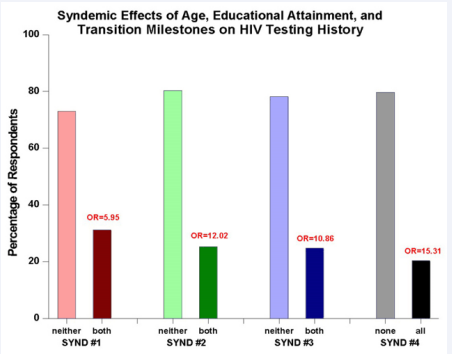

To ascertain whether or not there is evidence of syndemic effects in operation, three of the items contributing the most consequentially to the multivariate equation were combined into three separate dichotomous measures. These were: age (coded as persons aged 18-29 versus those who were older, based on post hoc analysis of the continuous age measure), educational attainment (at least a college graduate versus less education), and transition milestones (reached all five milestones versus reached none of the five transition milestones; persons who had reached any but not all of the milestones were excluded from this part of the analysis). Subsequently, these three measures were examined first in paired comparisons and then in a three-way comparison. Paired comparison #1 (shown in the graphic as Synd #1), examined the conjoint effects of age and educational attainment. Paired comparison #2 (Synd #2), examined the conjoint effects of age and transition milestones. Paired comparison #3 (Synd #3), examined the educational attainment and transition milestones. The three-way comparison (Synd #4) examined the combined effects of age and educational attainment and transition milestones. For each of these syndemic impact variables, dichotomous measures were constructed so as to indicate persons who had experienced both/all of the risk factors and persons who had experienced neither/none of the risk factors (Once again, persons experiencing one or some but not all of the risk factors for any particular comparison were eliminated from analysis).

RESULTS

Prevalence

Slightly more than one-half (51.5%), of the study participants reported having been tested for HIV at least once during their lifetimes. By far the most common reason for not being tested for HIV was adhering to the belief that it was unlikely that the person had ever been exposed to HIV (88.0%), followed by “no particular reason” (5.2%) and “doctor or health care provider never mentioned it” (2.0%). Of those who had ever been tested for HIV, 24.0% had been tested at some point during the year prior to interview. The remainder (76.0%) reported that their last HIV tests had been more than one full year prior to interview, with nearly one-quarter of these people (24.1%) not having been tested for HIV in more than five years. The HIV seropositivity rate among ever-tested persons was 1.3%.

Factors Associated with HIV Testing

Bivariate Analysis – The odds of having been tested for HIV at least once in one’s life were greater among persons who were: transgender women (OR = 1.57, CI95 = 1.50–1.65, p<.0001), older (OR = 1.05, CI95 = 1.05–1.05, p<.0001)–particularly those who were older than age 30 (OR = 4.12, CI95 = 3.91–4.34, p<.0001), African American (OR = 2.14, CI95 = 1.84–2.49, p<.0001), at least college graduates (OR = 2.67, CI95 = 2.54–2.81, p<.0001), married or “involved” with someone (OR = 2.05, CI95 = 1.92–2.19, p<.0001), binary in their gender identity (OR = 1.60, CI95 = 1.52– 1.68, p<.0001), not unemployed (OR = 1.32, CI95 = 1.25–1.39, p<.0001), not living near or below the poverty line (OR = 1.48, CI95 = 1.41–1.56, p<.0001), covered by medical/health insurance (OR = 1.12, CI95 = 1.04–1.20, p=.0025), substance misusers (OR= 1.96, CI95 = 1.87–2.06, p<.0001), and those who were victims of a greater number of different types of anti-transgender discrimination, harassment, and/or violence (OR = 1.14, CI95 = 1.13–1.15, p<.0001).

Additionally, reaching each of the various transition milestones was also associated with an increased likelihood of HIV testing: #1 (told any family members that one is transgender) (OR = 2.09, CI95 = 1.97–2.22, p<.0001), #2 (told all family members that one is transgender) (OR = 2.74, CI95 = 2.57–2.91, p<.0001), #3 (told any friends that one is transgender) (OR = 2.19, CI95 = 1.91– 2.50, p<.0001), #4 (told all friends that one is transgender) (OR = 1.46, CI95 = 1.39–1.54, p<.0001), #5 (told any coworkers and/or classmates that one is transgender) (OR = 1.78, CI95 = 1.68–1.88, p<.0001), #6 (told all coworkers and/or classmates that one is transgender) (OR = 2.40, CI95 = 2.27–2.54, p<.0001), #7 (changed name and/or gender on any legal documents) (OR = 2.89, CI95 = 2.75–3.04, p<.0001), #8 (changed name and gender on all legal documents) (OR = 3.04, CI95 = 2.73–3.38, p<.0001), #9 (began taking gender-affirming hormones) (OR = 3.51, CI95 = 3.33–3.68, p<.0001), #10 (had any gender-conforming surgical procedure) (OR = 3.52, CI95 = 3.34–3.73, p<.0001), and #11 (had all gender- conforming surgical procedures available to someone of his/her gender) (OR = 2.60, CI95 = 1.73–3.90, p<.0001).

Multivariate Analysis – Table 1 presents the results of the multivariate analysis, with nonsignificant contributors removed from the equation. It shows that thirteen items contributed uniquely and significantly to the model differentiating persons who had been HIV tested at least once in their lives from those who had not. These were: age (β = 0.25, p<.0001), race (β = 0.09, p<.0001), educational attainment (β = 0.15, p<.0001), relationship status (β = 0.03, p=.0007), self-identification as nonbinary (β = 0.06, p<.0001), substance abuse/misuse during the previous month (β = 0.18, p<.0001), the number of different types of anti-transgender discrimination, harassment, and/or violence experienced (β = 0.23, p<.0001), and level of psychological distress (β = 0.10, p<.0001). Additionally, the transition milestones played a significant role in respondents’ likelihood of being HIV tested, too, with five of them remaining in the final multivariate equation: having told all family members that one is transgender (β = 0.03, p=.0016), having told all of one’s schoolmates and/or coworkers that one is transgender (β = 0.05, p<.0001), changing one’s name and/or gender on any legal documents (β = 0.05, p<.0001), has begun taking gender- affirming hormones (β = 0.11, p<.0001), and has undergone at least one gender-conforming surgical procedure (β = 0.07, p<.0001). Together, these items explain approximately 28.8% of the variance.

Evidence of syndemic effects – When the effects of age, educational attainment, and transition milestones were examined in various combinations to assess their impact on HIV testing history, sizable syndemics effect were observed. Age + education: People who were aged 30 or older and who had at least completed college were nearly six times as likely as their peers who were under the age of 30 and who had less than a college degree to report having been tested for HIV at least once in their lives (OR = 5.95, CI95 = 5.56–6.37, p<.0001) (see Synd #1 in Figure 1).

Figure 1 Syndemic Effects of Age, Educational Attainment, and Transition Milestones on HIV Testing History.

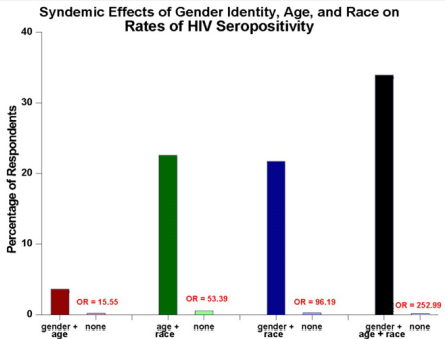

Figure 2 Syndemic Effects of Gender Identity, Age, and Race on Rates of HIV Seropositivity.

Age + transition milestones: Younger people who had not reached all five of the milestones were twelve times more likely than their older counterparts who had reached all of those transition milestones to report never having been tested for HIV during their lives (OR = 12.02, CI95 = 10.63–13.61, p<.0001). Education + transition milestones: The conjoint effects of lower levels of educational attainment and not reaching all of the transition milestones (Synd #3) led to a nearly-eleven times greater risk of having never been tested for HIV (OR = 10.86, CI95 = 9.46–12.44, p<.0001). Age + education + transition milestones: There was a fifteen-fold increase in the odds of HIV testing among older adults with at least a college education who had reached all of the transition milestones when compared to their less- well-educated, younger counterparts who had not reached those milestones (Synd #4) (OR = 15.31, CI95 = 13.09–17.92, p<.0001).

Factors Associated with Testing HIV-Positive

Bivariate analysis – Greater odds of being HIV seropositive were associated with: being a transgender female (OR = 6.77, CI95 = 4.43–10.35, p<.0001), being middle-aged (i.e., between ages of 40 and 59) (OR = 3.43, CI95 = 2.55–4.61, p<.0001), being African American (OR = 11.74, CI95 = 8.40–16.37, p<.0001), having less than a college education (OR = 3.00, CI95 = 2.13–4.23, p<.0001), not being married or “involved” with someone (OR = 1.86, CI95 = 1.22–2.85, p=.0035), having a binary gender identity (OR = 3.39, CI95 = 2.08–5.53, p<.0001), being unemployed (OR = 2.29, CI95 = 1.69–3.11, p<.0001), living near or below the poverty line (OR = 1.69, CI95 = 1.24–2.30, p=.0007), and being a substance misuser (OR = 1.42, CI95 = 1.06–1.92, p=.0196).

Additionally, reaching most of the various transition milestones was also associated with an increased likelihood of having tested positive for HIV. This was true for transition milestones: #1 (told any family members that one is transgender) (OR = 1.77, CI95 = 1.04–3.02, p=.0323–a marginal intergroup difference), #2 (told all family members that one is transgender) (OR = 2.25, CI95 = 1.67–3.04, p<.0001), #4 (told all friends that one is transgender) (OR = 2.13, CI95 = 1.58–2.88, p<.0001), #6 (told all coworkers and/or classmates that one is transgender) (OR = 2.00, CI95 = 1.40–2.87, p<.0001), #7 (changed one’s name and/or gender on any legal documents) (OR = 1.43, CI95 = 1.05– 1.93, p=.0214–a marginal intergroup difference), #9 (began taking gender-affirming hormones) (OR = 1.73, CI95 = 1.23– 2.42, p=.0013), and #10 (had any gender-conforming surgical procedures) (OR = 1.55, CI95 = 1.15–2.10, p=.0038).

Multivariate Analysis – Table 2 presents the findings for the multivariate analysis predicting the likelihood of being HIV- positive. Seven measures contributed uniquely and significantly to the equation: (1) being a transgender female (β = 0.48, p<.0001), (2) being middle-aged (β = 0.29, p<.0001), (3) being African American (β = 0.28, p<.0001), (4) having completed less than a bachelor’s degree educationally (β = 0.22, p<.0001),(5) not being married or “involved” with someone (β = 0.14, p=.0065), (6) being unemployed (β = 0.14, p=.0002), and (7) being a substance misuser (β = 0.14, p=0018). Together, these items explained 20.9% of the total variance.

Evidence of Syndemic Effects – When the effects of race, age, and gender identity were combined in various combinations to assess their impact on HIV seropositivity, very sizable syndemic effects were observed. Gender identity + Age: Transgender women who are middle-aged were much more likely to be HIV-positive than their male-identified counterparts who were younger or older than middle-aged (OR = 15.55, CI95 = 8.94–27.03, p<.0001). Age + Race: African Americans who were middle-aged were much more likely to be HIV-positive than their younger/older counterparts who were nonblack (OR = 53.39, CI95= 30.77–92.59, p<.0001). Gender identity + Race: Transgender women who are African American were much more likely to be HIV-positive than their counterparts who neither self-identified as a woman nor as an African American (OR = 96.19, CI95 = 55.87–166.67, p<.0001). Gender Identity + Age + Race: Middle- aged African American transgender women were vastly more likely than their counterparts who were other-than-middle-aged, nonblack, and transgender men to be HIV-positive (OR = 252.99, CI95 = 114.94–555.56, p<.0001).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, lifetime HIV testing rates were low (51.5%) and the percentage of respondents who had been tested for HIV during the preceding year was only 24.0% among persons who had ever been tested for HIV (that is, approximately 1 person in 8 study-wide). These figures fly in the face of the recommendations included in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, which has set as its goal that all persons with potential exposure to HIV be tested at least once each year [2]. HIV testing is considered to be one the primary means of curtailing the HIV epidemic in the United States. The low rates of lifetime HIV testing in the transgender population, coupled with the even- lower rates of recent testing, are of great concern because, without regular testing for HIV, there is an ongoing elevated chance of transgender persons becoming HIV-infected by and/or of transmitting HIV to their partners.

The present study also revealed that certain subpopulations of transgender individuals were at particularly great risk for never having been tested for HIV. Prominent among these were younger adults (particularly those under the age of 30), people who had less than a college education, people who belonged to a racial group other than African American, and those who had not reached the various transition milestones examined in conjunction with this research. The present study’s finding that younger adults are less likely than those who are older to report ever having been tested for HIV mirrors that reported by Patel and colleagues [16], based on their analysis of data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Also consistent with previous research is the present study’s finding that African Americans were more likely than all other racial groups to report having been tested for HIV at least once in their lives [17]. What these findings indicate, however, is that public health initiatives aimed at increasing HIV testing rates among transgender persons likely would benefit by targeting specific subgroups of transgender persons with targeted intervention messages.

This is particularly true when one considers the evidence derived by the present research with regard to the syndemic- type interaction effects observed among key predictors of HIV testing within the broader population of transgender adults. For example, when the conjoint effects of being 30 years of age or older and having at least a college degree were examined, the likelihood of having been tested for HIV increased almost six- fold. As another example, when the combined effects of age and reaching all of the transition milestones were considered, the odds of having been tested for HIV increased more than twelve- fold. If educational attainment is added to the mix, then the chances of having been tested for HIV increased even more, by greater than a factor of fifteen when compared to persons who were less-well-educated, younger, and who had not reached all of the transition milestones examined. Clearly, while HIV testing rates are low among transgender persons in general, certain subpopulations of transgender persons are at very great risk for never having been tested for HIV. This poses a great challenge to efforts designed to reduce the spread of HIV throughout the transgender community. Targeted outreach is warranted, and future research is needed to identify other specific subgroups within the broader population of transgender persons who are at greater-than-average need for campaigns designed to promote HIV testing. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [18], has written about this need, as has the National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center [19]. The present study’s findings buttress their recommendations.

The present research also yielded some interesting and important findings with regard to HIV seropositivity. Among respondents who had ever been tested for HIV, the seropositivity rate was 1.3%. Current estimates from the U.S. population-at- large suggest that 1,068,193 American adults were living with HIV as of 2021, at a time when the U.S. adult population reportedly consisted of approximately 258,350,000 persons [1,20].This equates to a population-wide HIV seropositivity rate of 0.4%. Thus, respondents in the present study had an HIV seropositivity rate that was roughly three times greater than that for the population-at-large. With a sizable proportion of the participants in the present study having never been tested for HIV, it is likely that the 1.3% prevalence figure is an underestimation of the true HIV seroprevalence among transgender adults. The best recent estimates available about the undercounting of existing- but-not-yet-diagnosed cases of HIV suggest that, if people living

with HIV but who are currently unaware of their HIV serostatus were included, there would be an additional 10-15% added to the officially diagnosed case counts [5]. Prior research suggested that the undercounting rate could be as high as 17.8% [21], and the current National HIV/AIDS Strategy reports the figure to be potentially as high as 40% [2]. Thus, it is likely that transgender persons are anywhere from four to six times more likely than adults in the population-at-large to be HIV-positive. Clearly, transgender individuals comprise a group at higher-than-average risk for contracting and potentially spreading HIV, and thus are a group in need of greater HIV education and intervention efforts.

Moreover, the present study’s findings indicate that certain subpopulations of transgender persons appear to be in particularly great need of targeted intervention. Most notably, this includes transgender women (who were more than six times more likely to be HIV-positive than their transgender male counterparts), African Americans (who were more than eleven times more likely to be HIV-infected than members of all other races), and middle-aged persons (who were more than three times as likely to be HIV-positive than their younger or older counterparts). Individuals possessing more than one of these characteristics were at an even greater risk of being HIV-infected, and persons possessing all three of these characteristics were at a very significantly elevated risk of testing positive for HIV. Merely providing HIV education and intervention initiatives targeting transgender persons may not prove to be sufficient, in light of the much, much higher rates of HIV observed in subpopulations within the broader transgender community (e.g., middle-aged African Americans or African Americans whose gender identity is female). These findings highlight the importance of crafting HIV information messages and HIV intervention programs with group-specific subpopulation-focused messages.

To date, only a few studies have reported on educational awareness initiatives or HIV intervention programs targeting specific subpopulations of transgender persons [22-25], and most of those that have been done have focused on the nexus of gender identity and race (i.e., typically, African American transgender women). Considerably more work needs to be done in this area–a point that was made previously by Neuman et al. [26], in their article focusing on HIV prevention initiatives targeting transgender individuals, and by Reback, Clark, and Fletcher [27], in their work targeting transgender women with multiple co-occurring health conditions. Martinez and colleagues’ [28], Philadelphia-based Transhealth Information Project is a rare exception in the scholarly literature, discussing the exact kind of transgender-focused HIV intervention initiative that the present authors consider to be lacking from the extant body of published studies. Another notable exception has been the work of Takahashi and colleagues [29], based on their syndemic-focused intervention project, Seeking Safety, aimed at helping transgender women of color but also examining key outcomes such as substance use and mental health. Also worthy of note is the New York City-based Healing Our Women project, which focused on HIV risk and HIV protective factors among HIV- positive transgender women of color [30].

In conclusion, this study has shown that HIV testing rates among transgender adults are low. In fact, testing rates are low enough that they are inadequate to prevent HIV from spreading throughout the transgender community and to the sex partners of transgender persons. Certain subgroups of transgender persons–particularly those who are younger, not well-educated, and a member of a racial group other than African American, among other salient characteristics–are at particularly great risk for not having been tested for HIV. Among persons who have been tested for HIV, seropositivity rates are at least three times greater among transgender individuals than they are in the adult population-at-large, and perhaps as much as six times greater when currently-infected persons who are unaware of their HIV serostatus are taken into account. Again, certain characteristics were found to be related to elevated odds of being HIV-positive, most notably being a transgender woman, a person who is middle-aged, and being African American. For HIV testing history and HIV serostatus alike, this research found strong evidence of powerful syndemic-type effects in operation, and they had a profound impact upon the odds that specific subgroups of transgender persons have been tested for HIV and/or infected with HIV.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2021. 2023.

- White House. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States, 2022-2025. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 2021.

- Pitasi MA, Oraka E, Clark H, Town M, DiNenno EA. HIV testing among transgender women and men–27 states and Guam, 2014-2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017; 66: 883-887.

- Rood BA, Kochaver JJ, McConnell EA, Ott MQ, Pantalone DW. Minority stressors associated with sexual risk behaviors and HIV testing in a U.S. sample of transgender individuals. AIDS Behav. 2018; 22: 3111- 3116.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data–United States and 6 dependent areas, 2019. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Rep. 2021; 26

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection, risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among transgender women– National HIV behavioral surveillance. 7 U.S. cities, 2019-2020. 2021.

- Baral SF, Poteat T, Stromdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet: Infectious Diseases. 2013; 13: 214-222.

- Hollander D. HIV testing patterns suggest need for services specifically geared to transgender individuals. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2015; 47: 277.

- Pitasi MA, Clark HA, Chavez PR, DiNenno EA, Delaney KP. HIV testing and linkage to care among transgender women who have sex with men: 23 U.S. cities. AIDS Behav. 2020; 24; 2442-2450.

- Clark H, Babu AS, Wiewel EW, Opoku J, Crepaz N. Diagnosed HIV infection in transgender adults and adolescents: Results from the National HIV Surveillance System, 2009-2014. AIDS Behav. 2017; 21:2774-2783.

- Eaton LA, Matthews DD, Driffin DD, Bukowski L, Wilson PA, Stall RD, et al. A multi-US city assessment of awareness and uptake of pre- exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among Black men and transgender women who have sex with men. Prev Sci. 2017; 18: 505-516.

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016.

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002; 32: 959-976.

- Klein H, Washington TA. Transition milestones and psychological distress in transgender adults. Urban Social Work. 2023; 7: 69-87.

- Klein H, Washington TA. Transition milestones, psychological distress, and suicidal ideation among transgender adults: A structural equation analysis. OMEGA. 2023.

- Patel D, Johnson CH, Krueger A, Maciak B, Belcher L, Harris N, et al. Trends in HIV testing among adults, aged 18-64 years, 2011-2017. AIDS Behav. 2020; 24: 532-539.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Adults who report ever receiving an HIV test by race/ethnicity. 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevention and care for transgender people. 2022.

- National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center. Delivering HIV prevention and care to transgender people. 2018.

- Statista. Resident population of the United States by sex and age as of July 1, 2021. 2023.

- Hall HI, An Q, Tang T, Song R, Chen M, Green T, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infection – United States, 2008- 2012. Monthly Morb Mortal Rep. 2015; 64: 657-662.

- Chandler CJ, Creasy SL, Adams BJ, Eaton LA, Whitfield DL.Characterizing biomedical HIV prevention awareness and use among black transgender women in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2021; 25:2929-2940.

- Maiorana A, Sevelius J, Keatley J, Rebchook G. She is like a sister to me’: Gender-affirming services and relationships are key to the implementation of HIV care engagement interventions with transgender women of color. AIDS Behav. 2021; 25: 72-83.

- Nemoto T, Iwamoto M, Suico S, Stanislaus V, Piroth K. Sociocultural contexts of access to HIV primary care and participant experience with an intervention project: African American transgender women living with HIV in Alameda County, California. AIDS Behav. 2021; 25: 84-95.

- Operario D, Gamarel KE, Iwamoto M, Suzuki S, Suico S, Darbes L, et al. Couples-focused prevention program to reduce HIV risk among transgender women and their primary male partners: Feasibility and promise of the Couples HIV Intervention Program. AIDS Behav. 2017; 21: 2452-2463.

- Neumann MS, Finlayson TJ, Pitts NL, Keatley J. Comprehensive HIV prevention for transgender persons. Am J Public Health. 2017; 107: 207-212.

- Reback CJ, Clark K, Fletcher JB. TransAction: A homegrown, theory- based, HIV risk reduction intervention for transgender women experiencing multiple health disparities. Sex Res Social Policy. 2019; 16: 408-418.

- Martinez O, Lopez N, Woodward T, Rodriguez-Madeira S, Icard L. Transhealth Information Project: A peer-led HIV prevention intervention to promote HIV protection for individuals of transgender experience. Health Soc Work. 2019; 44: 104-112.

- Takahashi LM, Tobin K, Li FY, Proff A, Candelario J. Healing transgender women of color in Los Angeles: A transgender-centric delivery of Seeking Safety. Int J Transgend Health. 2005; 23: 232-242.

- Collier KL, Colarossi LG, Hazel DS, Watson K, Wyatt GE. Healing Our Women for transgender women: Adaptation, acceptability, and pilot testing. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015; 27: 418-431.