Psychoanalytical psychotherapy of trauma from an object-relational perspective

- 1. Clinical Psychologist, VU Medical Center, Netherlands

Abstract

This article provides an overview of psychoanalytic thought on trauma from a relational perspective. I will first attempt to provide a historical overview. Then I will discuss clinical practice. All contemporary psychoanalytic practitioners know something about trauma, and each probably has a preference for a particular angle. So the limitation of this account is that it is my perspective, based on my experience. It is therefore inevitably incomplete.

Keywords

• Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy; Trauma; Psychoanalytic practitioners.

Citation

Draijer N (2025) Psychoanalytical psychotherapy of trauma from an object-relational perspective. Ann Psychiatry Ment Health 13(3): 1208.

INTRODUCTION

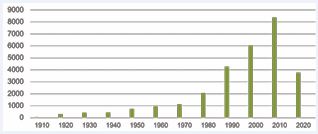

This article provides an overview of psychoanalytic thought on trauma from a relational perspective. I will first attempt to provide a historical overview. Then I will discuss clinical practice. All contemporary psychoanalytic practitioners know something about trauma, and each probably has a preference for a particular angle. So the limitation of this account is that it is my perspective, based on my experience. It is therefore inevitably incomplete. Secondly, this story is not about simple PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), because trauma is more than PTSD. It is not about neurobiology, not about stress hormones, the HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), the brain. And not about research. It is mainly about trauma that affects the personality structure, because that is where a relational psychoanalytic treatment is indicated. In order to get an overview over time, I asked myself: How much has been written about trauma by analysts? To answer that question, I used the PEP -Web Psychoanalytic Library to map the number of psychoanalytic publications with the concept of ‘trauma’ per decade (1900-present) (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of psychoanalytic publications with the concept of ‘trauma’ (PEP) per decade (1900 - present)

and the fourth from 1980 with the arrival of the women’s movement and the attention for sexual violence. From that moment onwards, the general interest in traumatization has also increased strongly: PTSD was included in the DSM for the first time in 1980, at that time III. I previously (2006) wrote a similar overview of publications on ‘sexual trauma’ and then noted that after the initial attention for this at the end of the nineteenth century, it actually went quiet for a long time and that attention for it was even actively withheld from psychoanalytic literature, until the women’s movement put an end to this. But the general conclusion is: trauma is a common thread throughout the history of psychoanalysis. And we are going to follow that thread. We will see that in this development of thinking about trauma two lines run through each other: 1) to what extent is there attention for trauma as a reality from outside (exogenous) or as a subjective experience, as a fantasy from within (endogenous)? And 2) does the perspective concern a one-person psychology with a therapist who knows versus a two-person psychology with a patient and therapist who are connected and respond to each other?

WHERE DO WE COME FROM?

During the second half of the 19th century, the Salpetrière in Paris was a center for research into nervous system disorders under the direction of the French neurologist Charcot. They investigated the ‘unconscious’ and ‘hysteria’ as a psychological disorder, using hypnosis. The illustration in which Charcot treats a lady, ‘Blanche’, in front of a whole room of (male) students, who is clearly in a different state of consciousness, is well-known. At that time, some 135 years ago, a collective concept of ‘Hysteria’ was used, including disorders that we would now call PTSD, Dissociative Disorders, Borderline Personality Disorder, histrionic or somatoform disorders. Pierre Janet – director of the Salpetrière from 1889 – had a great interest in the unconscious. He described - among other things in his dissertation 2’l’Automatisme Psychologique’ (1889) - how people place traumatic experiences outside their consciousness and called this ‘dissociation’. He also assumed a biological factor in this process. He took patients who reported incest seriously and used hypnosis in the treatment of dissociated memories. (see eg 34Van der Hart & Van der Kolk, 1989). He was the first psychologist to develop a systematic exposure treatment for post traumatic pathology.

FREUD AND THE SEXUAL TRAUMA: THREE PHASES

Also Sigmund Freud studied with Charcot and he too was fascinated by the unconscious. In his thinking about sexual trauma, three phases can be distinguished: the trauma-affect model [1], the seduction theory [2], and psychoanalysis: the drive or conflict model [3,4].Freud had been in contact with the physician Joseph Breuer since 1882 about the treatment of hysteria and started working with him. It has been suggested that the famous ‘talking cure’ of ‘Anna O’, in which the patient is allowed to tell whatever comes to mind, influenced the development of psychoanalysis. In 5’On the psychical mechanism of hysterical phenomena’ Freud & Breuer (1893) [1], write: “ Hysterics suffer mainly from reminiscences ” (p.58). And that “. each individual hysterical symptom immediately and permanently disappeared when we had succeeded in bringing clearly to light the memory of the event by which it was provoked and in arousing its accompanying affect, and when the patient had described that event in the greatest possible detail and had put the affect into words. Recollection without affect almost invariably produces no result. ” (p.57). We would say today: they describe exposure psychotherapy for PTSD.

Freud uses here – following Janet – a description of trauma as emotionally overwhelming. The sensory stimuli from outside exceed the stimulus threshold and the psyche becomes overwhelmed, is the (psychological) assumption. Hysterical patients then suffer from the consequences of emotionally overwhelming experiences in the past. We call that the trauma-affect model. For our practice today, this model remains valid. But it is a clear case of one-person psychology, a complaint-oriented, exposure treatment and the doctor knows.In ‘On the Etiology of Hysteria’ Freud [2], describes his discovery that only sexual traumas in early childhood are actually important for the development of neuroses. That is phase 2, the ‘ Seduction Theory ‘. He writes: “I maintain, then, that every case of hysteria rests on one or more episodes of premature sexual experience, which belong to early childhood and which, despite the decades which have elapsed since then, can be produced by means of analytic work. I regard this as an important revelation, as the discovery of a caput Nili – the source of the Nile – in the field of neuropathology …” [2].

Shortly after, phase 3 follows in his thinking: the beginning of psychoanalysis, the drive or conflict theory. Freud writes in his letters to Fliess (1897) that he no longer believes his hysterics [3]. He no longer believes his own theory of neurosis. He has disappointing results. He states that as a clinician you cannot distinguish between truth and imagination, to which much affect is linked. He also no longer believes that the experiences would occur as often as he first thought. They cannot therefore be at the root of all neuroses.

It was not until seven years after this discovery that he came out with this new theory in ‘Three Treatises on the Theory of Sexuality’ (1905a). The realization that sexual impulses are normally already active in very young children and do not require any external stimulation is the basis for Freud’s sexual theory (7letter 75, to Fliess, November 14, 1897; Freud, 1905a: 53). He based this step on his self-analysis. This step marked the beginning of psychoanalysis, because it placed priority in attention on the inner world, the psychic reality, on the fantasy world of the child as an etiological factor in neurotic development. Priority lies with the subjective inner world (fantasy) and with the exploration of childhood sexuality. He assumes,among other things, that seductive fantasies ward off memories of guilt-laden childhood masturbation.Although Freud also mentions in his later work that sexual abuse does indeed occur as a burdensome traumatic experience, the priority of the instinctual life, the inner conflicts about this, the fantasy, the subjectivity, form the core of his psychoanalysis. Where this leads I want to illustrate by means of the case of Dora.

The case of ‘Dora’ [4]

Although he does wonder in the text whether the two incidents of forced sexual advances reported by Dora can be called ‘traumatic’, and although he claims that he considers his ‘trauma theory not incorrect, but incomplete’, it is clear that he prioritises sexuality, sexual desires, above all else. Although Dora was sexually harassed by an adult, a family friend, Mr K., when she was 14, and Freud also knows that both Dora’s father and Mr K. are mendacious and put their own interests first. After all, her father is having an affair with Mr K’s wife. But Freud is so convinced of his own perspective - namely that repressed desires are making her hysterically ill - that he seems blind to her understandable resistance and aversion. He describes a situation in which Mr K. arranges for Dora to be alone with him when she is 14. He closes the shutters so that no one can see them and suddenly presses her against him and kisses her on the mouth. Dora reacts with intense disgust, which we could well understand today - “# MeToo” - tears herself away and runs away, but Freud says: “That was surely the situation to arouse a clear sensation of sexual excitement in a fourteen year-old, untouched girl.” (p.50) And he calls her behavior ‘completely hysterical’ (p.50). There are still analysts who assume only the primacy of the drive theory and the emphasis on sexuality. This view is vigorously defended, not only by Freud, but also by his followers. Apparently, in a paradigm shift, the previous theoretical model (a trauma-affect model) feels incompatible with the new one (the drive theory) [5]. I once called this ‘either-or’ thinking: one places reality (of the abuse) against desire and fantasy and places primacy with the drives, especially the sexual desires and their conflicts. These are seen as innate data, they come from within.I would say that it is of course not either-or, but both and. Incidentally, Freud again paid attention to traumatization following WWI, again in the form of an overstimulation model, either from within or from without [6]. He had therefore not distanced himself completely from a model that does justice to the traumatizing reality; only in the case of sexual traumatization this was more difficult.

Sandor Ferenczi

Sandor Ferenczi (1873-1933) thought fundamentally differently about this. He was a follower and good friend of Freud. He had studied medicine in Vienna and worked as a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in Budapest from 1897. He was a hospital doctor in a psychiatric clinic there and had – and this is an important fact – a much more serious patient population than Freud, who served more the neurotic upper class [7]. As a result, he saw a lot of affective neglect, abuse and maltreatment and therefore also more complex trauma and dissociative disorders. He advocated a more active treatment with these patients, with attention to reciprocity and what we would now call ‘intersubjectivity’ within the therapeutic relationship. Ferenczi wrote, among other things, the famous, but maligned by Freud, article “The Confusion of Tongues Between Adults and the Child [...]” in which he analyzes what children who are abused go through mentally. He says, among other things: “The children feel physically and morally helpless, their personality is still too insufficiently consolidated for them to be able to protest even if only in thought. The overwhelming power and authority of the adults renders them silent: often they are deprived of their senses. Yet that very fear, when it reaches its zenith, forces them automatically to surrender to the will of the aggressor, to anticipate each of his wishes and to submit to them, forgetting themselves entirely, to identify totally with the aggressor” [8]. So he describes here both dissociation (which we already knew from Janet and from Freud & Breuer), as well as ‘ splitting ‘, namely in the form of ‘identification with the aggressor’. The child ‘forgets himself’ and ‘identifies with the perspective of the perpetrator’: resulting in self-hatred and guilt for experiences for which it was not responsible. So: trauma leads to splitting!

As an example of this identification with the perspective of the aggressor, a short quote from Gerard Durlacher (1928-1996). From the age of 14 in 1942, he stayed in Westerbork, Theresienstadt and Auschwitz successively.He was 17 years old when he was the only one of his Jewish family to return from the concentration camp to the Netherlands. He wrote the beautiful book ‘Stripes at the Sky’ (1985) about this. This is an excerpt from a documentary about him by Cherry Duyns (a program in De Balie in 2021). In it, Durlacher says in response to Duyns’ question whether he felt ashamed in front of his children: “ I think so. I think so.” Duyns: “ Shame because you have been so humiliated?” “I think so. ……Look, of course the Germans succeeded. At that moment they turned us into vermin. They always propagated: the Jews are vermin. They turned us into vermin. And at a certain point you believe yourself that you are vermin. And that is not a pleasant thought. I think we came home with a serious inferiority complex. Maybe even worse than an inferiority complex. In fact, you were nothing at all anymore.”

In fact, you were nothing at all anymore: The sense of self, the identity, is fundamentally affected by chronic traumatization.Why is Ferenczi still important for us today, when it comes to our contemporary psychoanalytic treatment of (complex) trauma? Ferenczi did not only bring external reality into the analysis. He also drew attention to the fact that in early traumatization within dependent relationships, more happens than just emotional overwhelming: as mentioned, the identity, the sense of self, is affected, splitting occurs, and a child identifies with the perpetrator.In this way, a child is mentally cast out of paradise. It can no longer rely on its own intuition, feelings and impulses, but adapts to the perspective of the perpetrator, of the person on whom it is dependent. As a result, the connection with its own feelings – and its own interests, its own will, its own desires – is disrupted. This leads to a wide range of later complaints (depression, self-hatred, insecurity, a borderline organization of the personality, self-harm, etc.). In other words: the structure of the personality is affected. The self-esteem is destroyed, there is a lot of shame, the child feels wrong [9,10], as if it is not worth being loved. It loses trust in its fellow human beings and in itself. It takes the blame and responsibility for what happened upon itself and detaches itself from its own overwhelming feelings of loneliness, fear, pain and rage. In this way, it retains the illusion of the good, loving parent, but becomes bad itself. I have therefore called the preliminary study of the Dutch national survey into sexual abuse ‘The World Upside- Down’ [11,12].We see this mental violation later, for example, in Winnicott‘s [13] ‘ false self’ - the child who adapts to the needs of the parents - and in Alice Miller’s ‘The Drama of the Gifted Child’ (1979). You see it in children who are emotionally abandoned or who are exploited by narcissistically preoccupied parents to meet the needs of that parent [14]. It is a profound change in the internal psychological structure and a very persistent one. Patients reject the damaged side of themselves with force (they experience it as egodystonic, as ‘not-me’). For example, a patient with DID said, when I pointed out to her that she was carrying a little girl inside her who was crying: “I don’t want anything to do with that child!”

And a man says about the abuse at a young age by an uncle: “I’m just an idiot for letting that happen! Just an idiot.”

In fact, the beginning of object-relational thinking (the internal representations of self and other, the conflict) lies with Ferenczi. In this he anticipated the contemporary two-person psychology, in which the pathology unfolds between patient and therapist. He called attention to the relevance of countertransference as a source of information, therefore advocated a personal psychotherapy for psychotherapists (‘Know thyself’) and was at the cradle of a two-person, interactive and relational psychology within psychoanalysis. Above all, he understood the inner world of the abused child, banished from paradise forever, so well [15].

Ferenczi thus made a great contribution to our field, but did not receive recognition for it during his lifetime, because his viewpoint that a burdensome reality (exogenous) plays a role and is formative for the inner psychic structure, was for many analysts, including Freud himself, for a long time incompatible with a drive and fantasy perspective. His recognition was certainly sixty years in coming. Freud even attempted to dissuade Ferenczi from presenting The Confusion … in public at the 1932 Wiesbaden Psychoanalytic Conference. It took 17 years for an English translation (1949) to appear.

The British ‘Independents’: Fairbairn, Winnicott and Bowlby

Fairbairn, Winnicott and Bowlby are – following Ferenczi – all three object relational thinkers. They acknowledge the role of reality in the mental development of children (not merely instinct-driven). They give trauma a place in that development. They also influenced the development in the United States of self psychology and the current interpersonal, relational and intersubjective approaches in psychoanalysis (Jessica Benjamin for example). They work in the relationship. It is striking that all three of them worked with children. I will discuss themvery briefly.

First of all, W. Ronald D. Fairbairn (1889 – 1964); he is considered the founder of the object relations theory. He strongly rejected Freud’s drive theory and stated: it is not about drives (from within) as the primary source of motivation (pleasure seeking), but about the desire to maintain the bond with the objects and to seek safety there (object seeking). Relational, therefore. Fairbairn had an eye for trauma (as an exogenous influence). He marks the transition from a one-person psychology (or pathology) to a two-person psychology.Then Donald W. Winnicott (1896 – 1971) who said: “There is no such thing as a baby. ….One sees a ‘nursing couple’.” (1940; see 1952 and 1960). The development of a child’s personality, of its inner world, is relational and goes back to the interaction between mother and child. “The capacity for a one-body relationship follows that of a two-body relationship, through the introjection of the object. ” (1952) “ Traumatization (…) creates an internal situation of profound helplessness, and an experience of being abandoned by all good and helping persons and internal objects.” In other words: trauma is relational. And with traumatization you feel completely alone.John Bowlby (1907 – 1990) formulated the attachment theory. He pointed out the importance of bonds and loss experiences for the development of psychopathology and juvenile delinquency. “All humans develop an internal working model of the self and an internal working model of others .”And these ‘internal working models’ - mental representations of self and other - are unconscious and are based on early experiences with parents and caregivers [16]. Later (1970) his co-worker Mary Ainsworth will develop ‘ The Strange Situation Experiment’ to distinguish the different attachment styles in children between the ages of 9 and 30 months: that is how early attachment styles are transferred, so that is how early a relational reality plays a role in personality development. Bowlby, who has now been so influential in retrospect, was also looked down upon by the psychoanalytic community.

Klein, Kernberg and others

Melanie Klein (who was analyzed by Ferenczi) and later in her wake Otto Kernberg, take a slightly different position in this list. They are also object-relational thinkers, but they place the emphasis primarily (and solely) on the inner world. Trauma is only mentioned in passing. They find the aggression household important and consider aggression to be innate. Neither of them has an explicit interest in traumatic exogenous factors, but they focus on the unconscious fantasy life, on transference and countertransference. All threats ultimately come from within. The explicitly relational concept of ‘projective identification’, in which the therapist affectively ‘picks up’ what the patient is forcing upon him/her, is attributed to Melanie Klein .Kernberg has been explicitly criticized for paying relatively little attention to trauma. And he has since revised his perspective. For example, he recently wrote: “Severely negative internalized object relations relating to traumatic and intolerable aggressive and sexual experiences remain dynamically split off from positive representations. Thus, they (…) prevent the eventual integration of positive and negative experiences into a whole. This permanent split related to the dominance of aggression is reflected in the borderline personality organization.” (2023, p.7, underlining ND).

Nelleke Nicolai [17] writes: “The perpetrator is on the inside.” And about the split-off aggressive parts: “The internalized perpetrators is the precipitation of experiences with another (parent) that is experienced as strange and not one’s own.” That is correct, they are experienced as ego-dystonic, as not-I, and Fonagy [18], would possibly call them ‘alien selves ‘ : inherent to abuse and maltreatment is after all being incorrectly mirrored by the significant other (perpetrator).

In 1985, child psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Daniel Stern described in ‘The interpersonal world of the Infant ‘ how the developing baby, in interaction with the main caregivers, goes through different stages in the development of his sense of self or identity. His work, related to the attachment perspective, shows that the security of the child’s inner world and his affect regulation are formed depending on the reliability of the social and reciprocal (!) interactions with his parents or caregivers. Depending on these developmental stages, traumatic experiences have a different impact.

The realization that reality plays an important role is also penetrating into psychoanalysis. For example, the French psychoanalyst André Green (1983/1997) wrote a wonderful article about the impact on the inner world of a child when the mother suddenly disappears as a nurturing function when she has first been occupied for a long time with the care of a sibling and then becomes depressed and no longer responsive. He called it ‘The dead mother’, referring to the mother who is suddenly no longer there in an affective sense in reality and in the reflection of this in the inner world of the child.In summary, we see the following overview of theoretical developments:

|

From + 1930 Ferenczi (identification with the aggressor, split) |

|

From + 1950 Fairbairn object relations theory (it concerns the bond with the object) |

|

From + 1960: Winnicott (there are also just plain nasty parents) |

|

From 1950: Klein and later (1970) Kernberg: object relations; primacy of the inner world, aggression management important, innate |

|

From + 1980 Bowlby: the traumatic reality (loss experiences) plays a role (attachment theory) |

|

From 1985 Stern: The interpersonal world of the Infant: it matters when trauma happens. |

|

From + 1980 / 1990 Green: reality plays a role, also in the analysis. |

|

From + 1990 attachment theory, Fonagy: (in)secure attachment is socially transmitted in the first childhood years |

Where does this overview take us ? First of all, it brings us the and-and perspective. The recurring dilemma is: does the primacy in psychoanalytic psychotherapy lie with the inner world, fantasy, and/or with the traumatizing (overwhelming) reality? To me, the primacy lies with both, but more with the inner world, because ‘reality’ is also subjective and relational. After all, every experience enters an inner world that has already been formed. That is why an attachment perspective adds so much: patients often appear to be (in)securely attached when traumatization occurs, and insecure attachment in itself appears to increase the risk of PTSD [19]. Moreover, traumatization contributes to the insecurity of attachment (the introduction of the bad object that must be repressed/ dissociated). And finally, the population is relevant: Freud was talking about neurotics, while Ferenczi and those who followed his line mainly talked about patients with a borderline organization of the personality.In any case, with this overview we have arrived at a relational way of treating: the trauma story is played out within the treatment relationship. What meant huge, insurmountable paradigm shifts in the time of Ferenczi, Fairbairn and Bowlby no longer means that. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy from an intersubjective object-relational perspective starts from an inner conflict between the tendency to seek rapprochement on the one hand and to maintain distance / aggression on the other, and combines this with a recognition of a traumatizing reality and an attachment perspective. In any case, these are all psychoanalytic relational approaches that can be used in the treatment of complexly traumatized patients. What does that look like?

The shadow of the object

In ‘The Shadow of the Object. Psychoanalysis of the Unthought Known’ (1987), Christopher Bollas describes how the countertransference in the relationship with an analysand makes clear what must have happened in the relationship between the analysand as a baby and his mother. In the chapter ‘ The liar’ he describes how in this analysis of a notorious liar the analysand repeatedly leaves the analyst in despair, by telling stories about his adventures that turn out not to be true in the second instance. Bollas shows that the liar actively repeats what he had to passively endure as a small child, namely the daily abandonment by his unreliable mother who did important things in the world, but left the care of her small baby to various others every day. The repetition of traumatic experiences thus takes place in the transference, where the therapist takes the position of the damaged child and the patient takes the position of the perpetrator of the past, the neglectful, abandoning parent, who leaves the analyst in bewilderment and loneliness.This is another, unconscious manifestation of a ‘trauma story’. What we see is that the place of the past - of the trauma story - in a relational psychoanalytic treatment, lies in the present. In the transference and countertransference. In the now. For example, a severely traumatized woman whom I had been treating twice a week for at least three years using TFP (Transference Focused Psychotherapy) suddenly said very anxiously at one point: “What are you going to do to me?” She saw me as one of the perpetrators who had repeatedly abused and mistreated her.

Many contemporary, symptom-oriented trauma treatments are based on a conscious trauma story, which can be told and to which ‘exposure’ can take place. Or rather the other way around: ‘exposure’ trauma therapy assumes that there is a conscious story that can be told.In psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic psychotherapy we assume that what lives in the unconscious strives for expression. The inner conflict, the ‘trauma story’, is always looking for a way to be overcome and that is how the enactment comes about, through that repetition. Psychoanalytic psychotherapy makes use of this mechanism by taking the ‘enactments’ seriously and considering them as ‘points of entry’. This means that we try to decipher the unconscious, the non-’mentalized’ trauma story together with the patient. We do this, among other things, by identifying the countertransference and in particular our feelings - however strange or unreal. What comes our way in contact with the patient? What is that feeling? And how do we give that back to the patient?Long ago, I had a woman in psychoanalytic psychotherapy, twice a week, who had come with anxiety and panic complaints and had a borderline organization of the personality in psychodynamic terms. She had a very burdened history with abandonment by both parents at a very young age: first her father left and then her mother left her with acquaintances. As the psychotherapy progressed, she showed that she had one boyfriend after another. I adapted myself each time, remembered their names and peculiarities, but gradually noticed a feeling as if I always had to follow her, but never really got to her, because then she had again another boyfriend. When I shared this observation with her, she first thought I meant it moralistically, as if I was against different boyfriends. But I explained that it was something between her and me, that I had the impression that I always had to follow her and adapt to a new situation. Then she was shocked and said: “That’s exactly what my mother used to do! An endless line of boyfriends, who of course were always more important than me.”

The transference, the definition of object relations, comes to us through the countertransference, first of all through our feeling, and has to be deciphered in order to be understood, so that it can become conscious.

I had a man in psychoanalytic psychotherapy, an intellectual, and I experienced the conversations with him during the first three sessions as particularly entertaining and interesting. So at first I thought during the session: “Wow, how nice, how fascinating.” But then I got the feeling: “This is really very entertaining, what’s wrong with this?” And during the third or fourth session I gave him this back. I said – at that moment not yet understanding what it meant: “I noticed something in our contact: You are very entertaining.” Then he burst into tears and shouted: “The story of my life!” As a child of a parent with a concentration camp past, he had felt that he had to be entertaining in order to keep up the mood in his family of origin and to keep the oppression of the war memories out of his consciousness.The route by which unmentalized traumatic material comes to us, and sometimes that of the generation above, is through this ‘psychoanalytic listening and feeling’ to what reveals itself in the transference via our countertransference - by means of projective identification. The trauma story is not simply ‘told’, we pick it up via our sensitively tuned relational senses, our ‘ belly talk ‘ (as Yeomans would call this unconscious form of communication, personal communication). We try to give it back to our patients in digestible form, so that they can become aware of what they are telling us. So that they can begin to feel it and give it meaning.

Transference and countertransference in traumatized patients: a relational model

Psychoanalytic authors who have really given a boost to the systematic analysis of transference and

countertransference in victims of sexual abuse are Davies & Frawley [20]. They start from a relational treatment model. They describe that the therapist is constantly drawn into re-enactments, which are not so much ‘clinical errors’, but are the essence of the material to be analyzed.

In this, it is the task of the therapist to allow this to happen on the one hand, to be affectedly ‘messed with’, you might say, while at the same time being able to detach themselves from it in order to observe these re-enactments with some distance, to identify what is going on, then to contain this and finally to ‘return’ this observation to the patient in a digestible form. Therapeutic ‘neutrality’ lies in this relational model of thinking in the ability of the therapist to keep these reenactments fluid and ever changing [20].Davies & Frawley list a number of typical constellations in which practitioners of patients with histories of abuse find themselves.

|

Eight sexual abuse 'transference-countertransference positions' (Davies & Frawley, 1994) |

|

|

Unseen neglected child |

Parent who sees nothing and is not involved |

|

Helpless, powerless, raging victim |

Sadistic perpetrator |

|

Privileged, 'special' child |

Idealized, all-powerful savior |

|

Seduced child |

Seducer |

They refer to a whole series of analysts (Winnicott, Khan, Gill, Mitchell, Greenberg, Hofman and Bromberg) who all emphasize that the therapist not only observes but also participates in the relational world of the patient, actively involving him or her in the reenactment of the early relational paradigms. It is therefore a relational, interactive treatment.

Davies & Frawley endorse Fairbairns’ (1943) view that it is the intensity of attachment to ‘bad’ abusive objects that is so persistent. As a consequence, negative transference rears its head again and again, with the therapist being seen as untrustworthy, or uncomprehending, or even abusive, (deliberately) damaging.This ‘relational model’ of treatment can be called a two-person perspective, in which the therapist and the patient find themselves in ever-changing transference and countertransference constellations that need to be analyzed and understood together. It requires the therapist to constantly move between being drawn into a re-enactment and detachment from it, and to observe and then discuss what is happening between him or her and the patient. This assumes “that therapists can tolerate both proximity and are well separated, so that they can observe both the patient’s emotional life and their own at the same time. They must be able and willing to detach themselves from the patient’s coercive affective grip and to reflect on what is happening between them and the patient. To do this, they must be willing to use their own emotional life. “(Van Mosel & Draijer, 2016).The therapeutic relationship forms – according to Davies & Frawley [20] – both the foreground and the background against which the treatment takes place. As a background, the relationship is the consistent ‘ holding environment’ (Winnicott, 1960a), in which the patient gradually learns to trust. A ‘good enough’ space (Winnicott 1960b) [21], that becomes safe enough for the patient to eventually integrate the long-split-off self and other representations that had become fragmented by the traumatic experiences. As a foreground, it is the ‘arena’ in which maltreatment, abuse, neglect are revived, and where patient and therapist work through the often chaotic transference and countertransference relationships together.

As the (therapeutic) relationship deepens, more and more painful memories emerge, not as a ‘story’, but as unorganized, unsymbolized, or if you prefer, unmentalized, experiences, which confuse and frighten the patient, sometimes so much so that they want to stop the therapy.Carina is a woman with a complex dissociative identity disorder who I have had in TFP for 7 years now. Her mother prostituted her when she was little, she was given to strange men, locked up, starved and exposed to bizarre rituals.In a recent session she acted as if she were gasping for air. I let what was happening to her in front of me sink in, so confusing and strange. It was as if she was being strangled. I kept trying to contact her and told her what I thought I saw: “You are very anxious. It feels as if you are being strangled. That must be awful. Can you hear me? Can you try to look around you? You are safe here and it is 2024.” She calmed down and was shocked and confused. “This is happening all the time at home now,” she said. The next day she wrote to me that she found it a miserable experience, but that she felt better now. And two weeks later she told me that these flashbacks have not happened anymore, since she realized during our conversation what it is that she is going through.In the model of Davies & Frawley we recognize the object-relational Transference Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) of Otto Kernberg and his colleagues (Yeomans, Caligor, Clarkin, Diamond) in which tradition I myself was trained. It concerns ‘ordinary’, good psychoanalytic psychotherapy, which is based on a relational, interactional, two-person psychology, focused on the patient with a borderline personality organization, i.e. with an inner world that is characterized by splitting. This therapy can be used very well with traumatized patients with borderline or narcissistic problems (research shows that there is a lot of early childhood trauma among them, [22,23]. The strength of this object-relational model lies, among other things, in addressing aggression, aggression that is highly present in patients who were abused or mistreated as children, but is hidden under a guise of victimhood, self-harm and projection onto others. There is a great similarity with the model of Davies & Frawley, but with emphasis on the conflict between seeking rapprochement, longing for closeness on the one hand, versus ‘autonomy’ and aggression on the other. This is experienced by the patients themselves as a confusing change in state: as a ‘push’ and ‘pull’ within relationships. But ultimately these ‘push and pulls’ must become integrated in the form of tolerating ambivalences. Kernberg himself, incidentally, easily uses ‘old’ terms such as ‘the drives’ - which seems funny, since Fairbairn distanced himself from them so forcefully. Nowadays, people are apparently quite capable of doing justice to both desire and reality.The painful feelings about the past are acknowledged, named and ‘contained’ in the transference and thus slowly but surely become bearable for the patient. Present and past are hardly distinguished in the experience in a transference treatment of borderline patients; sometimes they merge seamlessly into the conversation, as if there is no distinction at all [24].In some patients, the negative transference dominates for a long time. Narcissistic patients seem to prefer fighting. Real contact is not the intention. They experience that as ‘safer’, because they abhor the dependency that was so dangerous at the time.

Just this week a patient said to me - after we had spent an entire hour trying to understand why she sometimes prefers to see me as an enemy who should be kept at a distance - “Yes, but that proximity is dangerous, because in the past when they were nice to me, they always ended up hurting me afterwards.”

Others – especially patients with narcissistic problems – hold on to the idea that the therapist does not understand them or they behave as if the therapist is not there. They thus repeat a constellation with uncomprehending or absent objects.All this time, etiological explanations (“Could it be that you are so angry because your mother wronged you.”) are pointless, because they carry the risk of being merely intellectual, cognitive exercises, a ‘story’ from which affect remains outside. Only when more integration has been achieved by discussing the transference in the here and now of the therapeutic relationship and when the bond with the therapist can be good rather than hostile more often, does it make sense to look at the past when the patient ends up there in the session.

From ‘re-enactment’ to Integration

Recovery for an adult patient therefore means repeatedly getting caught up in these reenactments within the transference-countertransference. The therapist allows himself to be carried away and contains, reflects and names what is being played out. This enables the patient to recognize the long-term split-off parts (self-states) and feelings – rage, loneliness, sadness, powerlessness etc. – as his own and to integrate them.

Aisha is in her late twenties when she comes to me; she was born in an Islamic country far away from here and came here as a child with her parents. She has a beautiful, impressive exterior that she carefully maintains, but a dark, sad interior. In the outside world she is a completely different person than at home, where she often lies in bed with the curtains closed. She hates herself and finds herself ugly, stupid and repulsive. She hears voices and harms herself. She tells me fairly early in our TFP treatment that she has a core that I would never, ever be able to reach. She shields it behind an impenetrable armor. No one can reach it.During the psychotherapy, her story gradually emerges: She is one of many children and as a child she was not only abused by a family member, but also emotionally neglected, beaten and employed as a housekeeper by her mother and married off to a much older man,Now, six years later and with the end of the therapy in sight, she tells me spontaneously that she has noticed that she is now one and the same person, whether at home, at work or with her family. She can admit all her feelings and take them seriously and she realizes that another person is another, with his own wishes, thoughts and problems. In short, her different sides, which were initially strictly separated, have slowly but surely been integrated, her traumatic experiences as well and above all her deeply negative self-esteem has been resolved. She can take setbacks.

What we see here is the integration of identity. She now experiences herself as one and the same in every situation.

DISCUSSION

What do psychoanalytic psychotherapists do?

What are our general standard techniques in (relational) psychoanalytic psychotherapy: what exactly do we do? We start from a relational, intersubjective model of treatment.We are inspired by observations of interactions with very young children and their mothers/caregivers, babies (see for example the work of Beatrice Beebe, and The Boston Change Process Study Group with Daniel Stern, Karlen Lyons Ruth, and Ed Tronick). We therefore find ‘ attunement ‘ important: empathically following the patient and all sides of the conflict, so with (relative) neutrality and abstinence. We are well connected to our own inner world: what do we feel in the contact; what is coming our way? Is there perhaps a case of projective identification? We immerse ourselves in the ‘theatre’ of the intersubjective reality of the therapeutic relationship [25], and we realize that this therapeutic relationship is a co-construction of two, interacting, active participants “with the subjectivities of both patient and analyst contributing to the form and content of the dialogue that emerges between them.” [26].We analyze the transference using the countertransference; affect is the ‘royal road ‘ to naming the ‘dyad’. We use all the senses, that is: ‘psychoanalytic listening’ and ‘ implicit relational knowing’ [26].

Modifications needed in traumatized patients?

The crucial question is of course: are modifications of these standard techniques necessary in complex traumatized patients? After all, there is then a strong avoidance of traumatic material: traumatic memories are dissociated / repressed / split off and emerge only slowly: there is usually no full ‘story’ or narrative available [27], and patients are deeply ambivalent about talking about the traumatic core [28]. The emergence of traumatic memories is accompanied by arousal and intense anxiety. Traumatic memories can also be fragmented: physical symptoms or fragments of flashbacks, images that one cannot immediately place. Ferenczi [8], already wrote: our technique can become more supportive in the treatment of serious trauma. Jessica Benjamin [29-31], emphasizes the need for (re)cognition, among other things, to be able to bridge the deep loneliness that trauma brings about.In some cases – for example in severe dissociative disorders – a pre-therapy phase may be necessary to learn stabilizing, affect-regulating techniques, such as relaxation or sensory exercises, to increase the possibilities to tolerate intense affect and ‘ the window of tolerance’. For full exposure, one can possibly use specific techniques (EMDR, bodywork, artistic expression), but this of course influences the transference relationship, so this is a delicate matter. One can possibly use a co-therapist for the EMDR. I would like to point out that not all traumatic memories can always be integrated: sometimes what happened is too unbearable (such as in organized - sadistic - sexual abuse at a very young age).Despite these obstacles inherent in traumatization, relational psychoanalytic psychotherapy seems to me the most appropriate method for treating complex trauma, because in complex trauma the structure of the personality is profoundly affected.

CONCLUSION: THE COMMON THREAD

This overview has shown that trauma is a common thread running through psychoanalytic theory formation. We described a development (a struggle, actually) from either-or thinking – either trauma (from outside) and emotional overwhelm or desire (from within) – to and- and thinking: both trauma and desire for connection with the other, so both reality and fantasy. We noted the transition from a one-person psychology to a two-person, intersubjective perspective. And we saw that splitting plays a central role in the impact of trauma, and that the ‘pathology’, the unmentalized ‘trauma story’ reveals itself within the transference and countertransference in the treatment relationship.Psychoanalytic psychotherapy is therefore by definition exposure treatment; after all, we follow the affect – the royal road. The goal is the integration of the personality and of the split-off memories. The pronounced relational variant - transference-oriented psychotherapy (TFP) - is therefore very helpful in the treatment of patients with complex trauma and dissociative disorders. It brings into focus the aggression that is abundantly present in this population and causes problems. In my opinion, therapists should be trained in both directive, symptom-oriented ‘trauma treatment’ (exposure and stabilization), and in this psychoanalytic psychotherapy. My own preference is to start with psychoanalytic psychotherapy / TFP and only if really necessary, for example if the traumatic material seems inaccessible, one can consider introducing a separate exposure track (EMDR for example).To quote Judith Herman, author of Trauma & Recovery (1992): trauma is relational and psychodynamic psychotherapy is therefore the ‘treatment of choice ‘ for complex traumatization

REFERENCES

- Freud S, Breuer J. On the psychical mechanism of hysterical phenomena. In: Freud, S. & Breuer, J. (1896). Studies on hysteria. Penguin Books Ltd, New York. 1974; 53-69

- Freud S. On the etiology of hysteria (Zur Atiologie der Hysterie).Clinical Reflections 1. Meppel: Boom, Meppel. 1993; 9-45.

- Freud S. Three treatises on the theory of sexuality (Drei Abhandlungensour Sexualtheory). Clinical Reflections. 1905a; 1: 47-177.

- Freud S. Fragment of the analysis of a case of hysteria [‘Dora’](Bruchstuck one Hysteria Analysis), Case Histories 2, Dutch edition. Meppel:Boom (1980,1988). 1905b.

- Draijer N. Psychoanalysis and the sexual trauma; the problem of either-or thinking. In: JE Verheugt (ed.) ‘ Psychoanalysis today. Assen: Van Gorcum. 2006; 287-306.

- Freud S. Introduction to Psychoanalysis of the war neuroses. Works. 1919; 8: 61.

- Kinet M. A few penultimate words. In: Franckx C. & Hebbrecht M. (eds.). The childhood trauma. Lost between tenderness and passion. Antwerp: Gompels & Svacina. 2023.

- Ferenczi S. The clinical diary of Sándor Ferenczi. ed. Dupont J. 1932.

- Frankel J. Exploring Ferenczi’s concept of identification with the aggressor: Its role in trauma, everyday life, and the therapeutic relationship. Psychoanalytic Dialogues. 2022; 12: 101-140.

- Kohut H. The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press. 1971.

- Draijer. The world turned upside down. Sexual abuse of children in the family. Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment, Directorate for the Coordination of Emancipation Policy (1985). 1984.

- Draijer N. Sexual traumatization in childhood. Long-term consequences of sexual abuse of girls by relatives. Academic Dissertation. Amsterdam: SUA Publishers. 1990.

- Winnicott DW. Metapsychological and Clinical Aspects of Regression Within the Psycho-Analytical Set-Up. Int J Psychoanalysis. 1995; 36: 16-26.

- Frankel J. Exploring Ferenczi’s concept of identification with the aggressor: Its role in trauma, everyday life, and the therapeutic relationship. Psychoanalytic Dialogues. 2002; 12: 101-140.

- Draijer N. Psychoanalysis, (child) trauma and Ferenczi. (Book review). J Psychoanalysis & its Applications. 2023; 29: 238-240.

- Bowlby J. Attachment. New York: Basic Books. 1969.

- Nicolai N. The is perpetrator on the inside. In: Goudswaard, H. (ed) Forgive or retaliate. On victims of intimate violence. 2000; 81-100.

- Fonagy P. Attachment and Borderline Personality Disorder. J American Psychoanalytic Association. 2000; 48: 1129-1146.

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. The relationship between insecure attachment and posttraumatic stress: Early life versus adulthood traumas. Psychological Trauma. 2015; 7: 324-332.

- Davies JM, Frawley MG. Treating the adult survivor of sexual abuse: A psychoanalytic perspective. New York: Basic Books. 1994.

- Winnicott DW. The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship. Internal J Psychoanalysis. 1960; 585-595.

- Herman JL, Perry JC, van der Kolk BA. Childhood trauma in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1989; 146: 490-495.

- Leichsenring F, Fonagy P, Heim N, Kernberg OF, Leweke F, Luyten P, et al. Borderline personality disorder: a comprehensive review of diagnosis and clinical presentation, etiology, treatment, and current controversies. World Psychiatry. 2024; 23: 4-25

- Fonagy P, Target M, Gergely G. Attachment and borderline personality disorder. A theory and some evidence review. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000; 23: 103-122.

- Tuckett. Knowing What Psychoanalysts Do and Doing What Psychoanalysts Know. Bloomsbury: Globe Pequot Publishing Group Inc. 2024.

- Lyons-Ruth K. The Two-Person Unconscious: IntersubjectiveDialogue, Enactive Relational Representation, and the Emergence of New Forms of Relational Organization. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 1999; 19: 576-617.

- Laub D, Auerhahn NC. Knowing and not Knowing Massive Psychic Trauma: Forms of Traumatic Memory. Int J Psychoanal. 1993; 74: 287-302.

- Vliegen N. Psychic space in single sexual trauma. J Psychoanalysis. 3rd Year. 1997; 3: 150-160.

- Benjamin J. An outline of intersubjectivity: The development of Recognition. Psychoanalytic Psychology. 1990; 7: 33-46.

- Benjamin J. Beyond doer and done to: an intersubjective view on thirdness. Psychoanalytic Quartely. 2004; 73: 5-46.

- Benjamin J. Beyond do and done to. Recognition Theory, Intersubjectivity and the Third. New York: Routledge. 2018.

- Aron L, Harris A. ‘Sándor Ferenczi: Discovery and Rediscovery’ Psychoananalytic Perspectives. 2010; 5-42.

- Ogden TH. On Projective Identification. Int J Psychoanalysis. 1979;60: 357-373.

- Draijer N. On the entanglement of present and past in Transference Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) in borderline patients. In: (Eds. Schulkes & Dil, Hendriksen, Roelofsen) The role of the past in psychotherapy. Assen: From Gorcum.

- Argelander H. Der psychoanalytic Dialog. Psyche—Z Psychoanal 22 325-339.

- Bion WR. Chapter Twenty-Seven. Learning from Experience. New York, Routledge. 1962; 3: 89-94.

- Mitchell SA, Aron L. Relational Psychoanalysis. The Emergence of a Tradition. London: The Analytic press. 1999.

- Clarkin JF, Yeomans FE, Kernberg OF. ‘Treatment of patients with Borderline Personality organization and a History of Sexual Abuse.’ In: Clarkin, Yeomans & Kernberg, Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality. Focusing on Object Relations. America Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington. 2006; 324-327.