Determining the Relative Weights of Health Care Compared to Other Quality of Life Components Using Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC)

- 1. Agribusiness, Applied Economics and Agriscience Education, North Carolina A&T State University, USA

Abstract

Background: Public health interventions aim to enhance overall Quality of Life (QOL) by improving access to health care services, promoting preventive health behaviors, and reducing health inequalities within communities. QOL is a multidimensional construct shaped by several factors, including the availability and effectiveness of health care services, food security, spiritual well-being, and community assets. Among these, health care has a particularly significant role, not only by reducing morbidity and mortality but also by influencing other determinants of well-being. However, the relative contribution of health care to QOL compared to other key dimensions has not been adequately quantified in previous studies.

Objective: This study aims to determine the relative weight of health care services in comparison to other major components affecting QOL and to provide evidence- based insights that may support public health policy design and resource allocation strategies.

Methods: Data were collected through a structured telephone survey conducted in 2023. Four main QOL dimensions were evaluated: Health Care, Food Security, Spiritual Well-being, and Community Assets. The Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC) method was applied to measure the relative importance of each dimension based on participants’ perceptions.

Results: The analysis revealed that Food Security carried the highest relative weight (30.32%), closely followed by Health Care (29.03%), while Spiritual Well- being contributed 26.57%, and Community Assets accounted for the smallest proportion (14.08%). These findings indicate that while food security remains slightly more influential in determining QOL, access to health care is nearly equally critical.

Conclusions: This study highlights the central role of health care services in improving quality of life within communities. Policies that focus on expanding access to primary care, strengthening preventive health programs, and reducing disparities in health services are likely to generate substantial improvements in overall well-being. The findings also emphasize the need for integrated public health strategies that combine efforts to secure adequate nutrition, improve health systems, and enhance social and spiritual well-being.

Keywords

• Public Health

• Health Care Services

• Quality of Life

• Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison

• Health Policy

Citation

Thomas TW, Cankurt M (2025) Determining the Relative Weights of Health Care Compared to Other Quality of Life Components Using Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC). Ann Public Health Res 12(2): 1140.

INTRODUCTION

Quality of Life (QOL) is a broad and multidimensional concept, encompassing not only health but also food security, spiritual well-being, and access to community assets. Over the years, researchers have emphasized that improvements in QOL cannot be attributed to a single factor; rather, it is the interplay among these dimensions that shapes the lived experiences of individuals and communities [1-3]. Still, one pressing question continues to guide both scholarship and policy: To what extent does health—particularly access to health care—contribute to quality of life compared to other factors? Health is often considered the foundation of well-being. Without good health and access to care, other aspects of life—such as education, employment, or community engagement—are difficult to sustain. Preventive health systems and equitable care reduce morbidity, extend longevity, and allow individuals to participate more fully in social and economic life. For instance, studies have shown that communities with reliable health systems experience not only lower mortality but also better food security outcomes, higher productivity, and stronger resilience to shocks [2]. In this sense, health operates as both a direct and an indirect driver of overall QOL. Quality of Life (QOL) is defined as a multidimensional concept encompassing physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains [4-7]. In the domain of health research, the measurement of Quality of Life (QOL) is frequently associated with Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), emphasizing factors such as morbidity, functional status, and access to healthcare services [8,9]. However, broader social science perspectives also include economic security, social connectedness, and community participation [10-12]. A common limitation of these approaches is that they rely on additive indices or standardized tools where domains are either equally weighted or weighted based on normative assumptions by researchers [13,14]. While these frameworks do facilitate comparisons across different population groups, they frequently obscure the subjective importance individuals ascribe to different areas of life. A paucity of studies has endeavored to directly capture people’s priorities regarding dimensions of quality of life. These studies have typically used discrete choice or best-worst scaling methods [15,16]. However, these approaches are rarely observed in US contexts, where structural inequalities have the potential to influence the significance of sectors such as healthcare or food security, and where services are often deficient. This discrepancy underscores the necessity for empirical methodologies, such as fuzzy pair wise comparison, which can elucidate how communities evaluate quality of life domains in practice.To capture this complexity, our study focused on four critical QOL dimensions: health care, food security, spiritual well-being, and community assets. These components were selected because they consistently emerge in both theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence from ethnographic studies researchers conducted as central to human well-being. Adequate access to health care is a cornerstone of QOL, improving not only physical health but also reducing inequalities across populations [2]. Food security is a basic biological and social determinant, influencing both physical health and community resilience [1]. Spiritual well-being, while less tangible, has been demonstrated to enhance psychological stability and life satisfaction, particularly in populations facing hardship [3]. Finally, community assets—such as local resources, civic networks, and social infrastructure—provide pathways for participation and belonging, which in turn strengthen overall life satisfaction [4]. These dimensions also align with our prior research in underserved communities in Guilford County, North Carolina, where residents repeatedly highlighted these areas when describing their lived experiences of QOL [17]. This study addresses the discrepancy which can arise from using discrete choice and best-worst scaling methods discussed above. It does this by applying the Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC) method to determine the comparative importance of health care relative to food security, spiritual well-being, and community assets. Unlike traditional measures that rely only on objectivehealth indicators, this approach captures subjective evaluations directly from community members. By doing so, it provides insights into how people themselves rank these dimensions, offering evidence that can inform both policy design and the allocation of public resources. The aim of this study is to identify the relative weight of health care services in shaping QOL, as perceived by individuals, and to evaluate whether health care is considered more important than other major dimensions. H1: According to individuals’ perceptions, the relative weight of health care in determining Quality of Life is higher than that of other components. By integrating subjective perceptions with quantitative analysis, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of QOL determinants. It provides policymakers, community planners, and public health professionals with evidence on how health care is valued in relation to other critical domains of life, ultimately supporting the development of targeted and more effective strategies to enhance well-being.

METHODOLOGY

Research Design

In defining a structural QOL model, the initial model that comes to mind is that utilized by the WHO. According to this model, QOL is comprised of six components: physical health, psychological health, level of independence, social relationships, environment, and spiritual well-being [18,19]. In other seminal studies, dimensions such as spiritual wellbeing, food security and community assets have been added to these variables [20-22]. According to our research design, we first conducted in-depth interviews to identify the components of the community’s quality of life model. The components we obtained were consistent with previous literature. Given that the community of focus in our study is predominantly composed of individuals from relatively low-education and low-income communities within Guilford County, North Carolina, United States, we have endeavored to maintain the structural model in a manner that is as simple and straightforward as possible.In considering the data gathered from participants and the existing literature, this study incorporates six key factors as influencing the Quality of Life. These variables are postulated to impact the quality of life, as illustrated in Figure 1. Our hypothesis is that each of these variables (health care, spiritual well-being, food security, and community assets) has an impact on quality of life (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Structural Model of QOL.

Data Collection

The study was conducted in Guilford County, North Carolina, in 2023. Data were collected from a sample of 280 individuals, determined according to standard sampling procedures for a 95% confidence interval and a 6% margin of error from the underserved community. Participants included in the study were purchased from a sampling company based on the sampling parameters researchers provided. A structured telephone survey was developed to collect quantitative data. The questionnaire incorporated the identified factors using a Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC) format, which was administered through the Qualtrics online platform. The survey was constructed to capture individuals’ perceptions of Quality of Life (QOL) determinant. See figure 1. Each participant was asked to make pairwise comparisons between these dimensions, indicating not only which was more important to them, but also the intensity of that preference. Although the task was simple in design, it often required multiple attempts to ensure clarity and accurate responses. Survey responses were recorded in a secure online database. The dataset was reviewed for quality control. Incomplete or logically inconsistent responses, such as contradictory selections, were removed to maintain the integrity and reliability of the analysis [22,23]. Ultimately, 208 valid responses were included in the final analysis. Removing inconsistent questionnaires from the dataset is a crucial step to improve the quality of the survey data and ensure the reliability of the results [24]. Inconsistencies may result from contradictions, denials or illogical responses. Eliminating such data contributes to a more solid foundation for analysis. A prior study conducted at the University of North Carolina emphasized that removing inconsistent or misleading data from an analysis can increase the reliability of the results [25,26]. We subjected our data to this refinement process [27]. By removing these data, the sample size decreased to 217. So,the margin of error in the representativeness of the sample compared to the population increased slightly but was still within acceptable limits.

Analytical Approach

The Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC) method was used to determine the relative weight of each QOL component. This method extends classical pairwise comparison by incorporating fuzzy set theory, which accounts for the uncertainty and imprecision inherent in human judgment [24]. Respondents’ choices were transformed into fuzzy numbers, which allowed preferences to be expressed on a continuum rather than as strict dichotomies.Fuzzy theory began with a paper on ?fuzzy sets by Lotfi A. Zadeh. Fuzzy set theory is an extension of crisp set theory, allowing for graded or partial membership rather than only full inclusion or exclusion. Fuzzy sets are sets with boundaries that are not precise. Thus, fuzzy sets describe ranges of vague and soft boundaries by degree of membership [28,29]. The membership in a fuzzy set is a matter of degree [30]. A fuzzy set is characterized by a membership function, which assigns an arbitrary real value between zero and one for each element of the universe of discourse [31]. FPC was first used by Van Kooten, Schoney and Hayward to study farmers’ goal hierarchies for use in multiple objective decision making [32]. The first step in FPC approach used in this study is data collection using a unit line segment as illustrated in Figure 2 [33].

Figure 2 Fuzzy method for making pair-wise comparison between advertisement methods D and T.

We use the Van Kooten et al. study as an illustrative example. In the study, two advertisement methods, D (field demonstration) and T (factory trips), are located at opposite ends of the unit line. Farmers were asked to place a mark on the line to indicate the degree of their preferred advertisement method. A measure of the degree of preference for advertisement method D over T, rDT , is obtained by measuring the distance from the farmer‘s mark to the D endpoint. The total distance from D to T equals 1. If rDT 0.5, then advertisement method D is preferred to T. rDT =1 or rDT =0 indicates absolute preference for advertisement method D over T. For example, if rDT =1, then advertisement method D is absolutely preferred to T [34,35].In our study, we employed four QOL components. The number of pair-wise comparisons, λ, can be calculated as follows: λ = n∗(n −1) / 2 where n = the number of QOL components. Thus, an individual made 6 pair-wise comparisons in a personal interview.

In the second step of FPC, for each paired comparison (i,j), rij (i≠j) is obtained. rij ‘s values are collected directly from community members. Also, rij (i≠j) is a measure of the degree by which the community member prefers QOL component i to component j and rji =1- rij represents the degree by which j is preferred to i. Following Van Kooten et al., the individual’s fuzzy preference matrix R with elements can be constructed as follows:

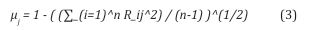

Finally, a measure of preference, μ, can be calculated for each QOL component by using the individual’s preference matrix R. The intensity of each preference is measured separately by the following equation:

μj has a range in the closed interval [0,1]. The larger value of μj indicates a greater intensity of preference for a QOL component j. As a result, the individual’s preferences are ranked from most to least preferable by evaluating the μ values.

To analyze component preference ratings derived from FPC, nonparametric statistical tests are employed [36]. The Friedman test is used to determine whether the QOL components are equally important within a block, which represents an individual’s rankings of QOL components according to his/her preferences. Since four components are presented to individuals, each row includes four values indicating the degree of preference for the QOL components. The null hypothesis states that there is no difference in preferences for the QOL components among individuals; alternatively, at least one component is preferred over the others. Another nonparametric test, Kendall‘s W, can be viewed as a normalization of the Friedman test. Kendall‘s W measures the level of agreement among more than two sets of rankings [37]. It ranges from 0 (no agreement) to 1 (complete agreement).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section presents the findings from the FPC analysis of the four quality-of-life components: health care,food security, spiritual well-being, and community assets. Following the cleaning of survey data, 217 valid responses were analyzed to estimate the relative weights assigned to each component. Results are reported in two stages: first, the descriptive characteristics of the sample, and second, the comparative importance of the domains derived from FPC weights. Statistical tests, including the Friedman procedure, were employed to assess the significance of observed differences. Table 1 shows the number and percentage distribution of by these variables according to their subgroups. The findings obtained from the sample in Table 1 are compared and interpreted with respect to Guilford County, NC state data and US averages.

Table 1: The values of demographic variables by subgroups.

|

Variables |

Categories |

Count |

% |

|

Gender |

Female |

124 |

57.14 |

|

Male |

84 |

38.70 |

|

|

PNR or missing* |

9 |

4.14 |

|

|

Age |

Young Adults (18-24) |

5 |

2.30 |

|

Adults (25-54) |

114 |

52.53 |

|

|

Early Seniors (55-64) |

44 |

20.28 |

|

|

Seniors (65+) |

43 |

19.82 |

|

|

PNR or missing* |

11 |

5.07 |

|

|

Race |

American Indian or Alaska Native |

3 |

1.40 |

|

Black or African American |

88 |

40.60 |

|

|

White |

115 |

53.00 |

|

|

PNR or missing |

11 |

5.10 |

|

|

Education |

Master’s degree or higher |

59 |

27.20 |

|

Bachelor’s degree |

76 |

35.00 |

|

|

Associate’s degree |

25 |

11.50 |

|

|

Some college but did not complete degree |

26 |

12.00 |

|

|

High school graduate or GED completed |

9 |

4.10 |

|

|

Some high school |

1 |

0.50 |

|

|

Prefer not to respond |

13 |

6.00 |

|

|

PNR or missing |

8 |

3.70 |

|

|

Relationship |

Married and living with spouse |

102 |

47.00 |

|

Married and not living with spouse |

17 |

7.80 |

|

|

Not in a committed relationship (i.e., single) |

46 |

21.20 |

|

|

Not married but in a committed relationship |

11 |

5.10 |

|

|

Not sure |

3 |

1.40 |

|

|

PNR or missing |

28 |

12.90 |

|

|

Employment |

Working full time, 35 hrs/wk or more |

133 |

61.30 |

|

Working part-time, less than 35 hrs./wk |

7 |

3.20 |

|

|

Retired |

53 |

24.40 |

|

|

A full-time stay-at-home parent |

8 |

3.70 |

|

|

Unemployed |

6 |

2.80 |

|

|

Disabled, not able to work |

1 |

0.50 |

|

|

PNR or missing |

9 |

4.10 |

* Prefer not to respond or missing value; ** Includes self-employed.

Gender: The sample has a higher proportion of Female respondents (59.62%) compared to Male respondents (40.39%). Guilford County and the U.S. exhibit a slightly more balanced gender distribution, with females accounting for approximately 52% of the population [38,39].

Age: The sample is predominantly made up of adults (52.53%), followed by Early Seniors (20.28%) and Seniors (19.82%), with a lower proportion of Young Adults (2.30%). In contrast, Guilford County has approximately 9% of the population between the ages of 18-24 and 16% who are 65 years of age or older [38,39]. Nationally, the US population has a higher proportion of young adults at 21% and a smaller elderly population at 16% [38]. The under-representation of young adults is considered to be limited and may fail to fully reflect the perspectives of this community.

Race: The racial composition is primarily White (53.00%) and Black or African American (40.60%), with smaller representations of American Indian or Alaska Native (1.40%). Guilford County’s racial demographics indicate 56% White and 35% Black or African American [39], aligning closely with the sample. Nationally, the proportions are 60% White and 13.6% Black [38]. The elevated representation of Black participants aligns more closely with Guilford County than national averages, highlighting the region’s unique demographic composition.

Education: Participants with a Bachelor’s degree (35.00%) and Master’s degree or higher (27.20%) are prominent in the sample, collectively surpassing 60% of respondents. Comparatively, in Guilford County, approximately 30% of residents hold a Bachelor’s degree and 14% hold graduate or professional degrees [40]. Nationally, these rates are 21% and 13%, respectively [38]. The sample reflects a higher education level than both regional and national averages, suggesting a potentially more specialized or affluent respondent pool.

Relationship Status: Nearly half of the participants are married and living with their spouse (47.00%), while 21.20% are single. Guilford County reports a marriage rate of 43%, with 37% of adult’s single [38]. Nationally, the marriage rate is 48%, with a similar proportion of singles [41]. It is observed that the calculated relationship values in the sample are close to the NC and national values.

Employment: The majority of respondents work full time (61.30%), while 24.40% are retired. Guilford County’s labor force participation rate is 63%, closely reflecting the employment trend of this sample [40]. Nationally, the labor force participation rate is 62.6% [42]. It can be seen that the data obtained from the samples are close to the county, state and national values. This study applied the Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison method to evaluate how individuals perceive the relative importance of health care in relation to other determinants of QOL. The Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC) analysis provided weighted scores for each QOL dimension (Table 2).

Table 2: Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison Analysis Results.

|

Alternative Names |

Relative Importance % |

Mean |

St.Dev. |

Median |

Max |

Min |

|

Health Care |

29.03 |

0.534 |

0.150 |

0.500 |

0.900 |

0.210 |

|

Food Security |

30.32 |

0.557 |

0.170 |

0.576 |

0.900 |

0.100 |

|

Spiritual Wellbeing |

26.57 |

0.488 |

0.214 |

0.500 |

0.900 |

0.100 |

|

Community Assets |

14.08 |

0.259 |

0.141 |

0.210 |

0.900 |

0.100 |

Results indicated that Food Security (30.32%) carried the highest relative importance, followed closely by Health Care (29.03%). Spiritual Well-Being was ranked third (26.57%), while Community Assets had the lowest relative importance (14.08%).

Friedman test confirmed significant differences among the four QOL components (Chi Square222.12, p< 0.01), rejecting the null hypothesis that all dimensions were equally weighted. This suggests that participants consistently perceived the four dimensions as having distinct contributions to their overall quality of life.

The Findings Highlight Three Main Points:

Health care ranked as the second most important dimension, nearly equal to food security. This supports our hypothesis (H1) that health care would be perceived as highly influential in determining QOL. The weight of health care (29.03%) underscores its central role not only in reducing morbidity and mortality, but also in shaping other areas of well-being. These findings align with recent literature showing that access to equitable health care is directly tied to improved life satisfaction and social stability [2-35]. Interestingly, food security (30.32%) was perceived as marginally more important than health care. This reflects the immediacy of food needs in daily life: individuals often perceive food availability and affordability as more urgent than access to medical services. Recent studies confirm that food insecurity significantly undermines perceived well-being, particularly in underserved and low-income populations [1]. The close proximity between food security and health care weights suggests these two domains are deeply interdependent. Spiritual well-being emerged as the third most

important domain, with a relative weight close to food security and health care. This finding suggests that beyond material and clinical factors, residents place strong value on meaning, resilience, and inner resources in sustaining quality of life. Prior studies confirm that spirituality often buffers against stress and health challenges in disadvantaged settings [43,44]. Thus, spiritual well-being should not be considered peripheral but rather an integral dimension alongside basic needs such as food and health care.

In contrast, community assets received the lowest relative weight. This pattern may reflect limited access to shared facilities and neighborhood resources in underserved areas, where immediate concerns such as food and health dominate decision-making. Previous research shows that when basic needs are insecure, individuals tend to undervalue broader community amenities [45,46]. Moreover, studies in food desert and low-income urban areas find that residents often perceive community infrastructure as underdeveloped or inequitably distributed, reducing its perceived relevance to daily well-being [47,48]. Consequently, the low weighting for community assets in this study may signal both structural deficits and a prioritization hierarchy shaped by necessity.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND PRACTICE

The findings indicate that food security, healthcare, and spiritual well-being collectively form triple pillars of QOL foundation in communities with lower income and limited educational opportunities. For residents in such settings, daily survival and resilience are contingent not only on meeting nutritional and medical needs but also on sustaining psychological and spiritual resources that provide meaning and hope amidst structural constraints. This interdependence suggests that policy interventions should go beyond fragmented sectoral approaches and instead design programs that address material scarcity while also nurturing spiritual/psychological well-being.

Within this triad, health care emerges as a particularly strategic lever. In contexts where resources are limited, inadequate preventive care and fragmented access often create a cycle where untreated conditions exacerbate financial strain and food insecurity. The strategic strengthening of local health systems through the implementation of affordable clinics, community-based health workers, and culturally sensitive services can generate a range of spillover benefits. These benefits include the reduction of household economic vulnerability, the enhancement of nutritional stability, and the facilitation of increased participation in community life.For populations with limited access to formal education, health programs that integrate treatment with education (e.g., nutrition counseling, chronic disease prevention workshops) could prove to be particularly effective. These programs simultaneously build capacity and address immediate needs. In this sense, healthcare is about more than just treating illness; it also provides a foundation for addressing the challenges that often leave many underserved communities vulnerable.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

While the FPC method captures perceptions with greater nuance than binary ranking, the study is limited to one geographic region (Guilford County, NC). Future studies should extend the analysis across different regions and populations, and combine FPC with longitudinal data to explore how perceptions shift over time. Additionally, integrating FPC with methods like Best–Worst Scaling or fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making may enrich understanding of QOL determinants.

CONCLUSION

This study examined the relative importance of four Quality of Life (QOL) dimensions (health care, food security, spiritual well-being, and community assets) using the Fuzzy Pairwise Comparison (FPC) method. The results demonstrated that food security (30.32%) and health care (29.03%) were perceived as the most critical components of QOL, followed by spiritual well-being (26.57%) and community assets (14.08%). Statistical tests confirmed that these differences were significant, highlighting the distinct role each dimension plays in shaping individual perceptions of well-being. The findings of this study suggest that food security, health care, and spiritual well-being together form the triple pillars of QOL foundation in underserved communities. Policies that address only one or two of these areas risk leaving critical gaps unfilled, as residents’ daily survival and resilience depend on the interaction of all three. For example, adequate nutrition supports physical health and reduces the incidence of chronic disease, while spiritual well-being fosters psychological resilience that allows individuals to navigate adversity. Designing integrated interventions that deliberately target these interconnections will likely yield the greatest improvements in well-being. Within this triad, health care emerges as a particularly strategic lever. In underserved contexts, inadequate preventive care and fragmented access often create a cycle where untreated conditions exacerbate financial strain and food insecurity. Strengthening local health systems (through affordable clinics, community-based health workers, and culturally sensitive services) can therefore generate spillover benefits: reducing household economic vulnerability, enhancing nutritional stability, and enabling greater participation in community life. For populations with limited formal education, accessible health programs that combine treatment with education (e.g., nutrition counseling, chronic disease prevention workshops) are especially powerful, as they simultaneously build capacity and address immediate needs. In this sense, health care does more than treat illness; it anchors a pathway out of the vulnerability that defines many underserved communities. At the same time, the low weight assigned to community assets should not be dismissed. While residents prioritize immediate needs such as food and health, the lack of value placed on community resources may reflect structural deficits in public infrastructure and social capital. Strengthening these assets—through investment in safe public spaces, accessible social programs, and civic networks—can create conditions where health and food security are more effectively sustained over the long term. Importantly, improving community assets also enhances collective efficacy, which has been shown to buffer against neighborhood-level inequalities.Taken together, these insights call for transdisciplinary systems oriented multi-sectoral, equity-oriented strategies that treat health care, food security, and spiritual well-being as interdependent priorities, while simultaneously investing in the community asset fabric that supports them. Such an approach not only addresses the immediate vulnerabilities of underserved populations but also lays the groundwork for sustainable improvements in quality of life.

REFERENCES

- Suasnabar JMH, Hanmer J, DeWalt DA, McLouth LE, Ford CG, Pustejovsky JE, et al. Exploring the Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life and Broader Instruments: A Dimensionality Analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2024; 345: 116003.

- Hanmer J, DeWalt DA, Berkowitz SA. Association between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life: A Nationally Representative Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2021; 36: 1638-1647.

- McLouth LE, Ford CG, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, Sherman AC, Trevino K, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Effects of Psychosocial Interventions on Spiritual Well-Being in Adults with Cancer. Psychooncol. 2021; 30: 147-158.

- Munford LA, Wilding A, Bower P, Sutton M. Effects of Participating in Community Assets on Quality of Life and Costs of Care: Longitudinal Cohort Study of Older People in England. BMJ Open. 2020; 10: e033186.

- Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998; 28: 551-558.

- Felce D, Perry J. Quality of life: Its definition and measurement. Res inDev Disabil. 1995; 16: 51-74.

- Schalock RL. The concept of quality of life: What we know and do not know. J of Intellect Disabil Res. 2004; 48: 203-216.

- Patrick DL, Erickson P. Health status and health policy: Quality of life in health care evaluation and resource allocation. Oxford University Press. 1993.

- Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality oflife. Ann of Intern Med. 1993; 118: 622-629.

- Cummins RA. Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. J of Intellect Disabil Res. 2005; 49: 699-706.

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, et al. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indic Res. 2010; 97: 143-156.

- Veenhoven R. The four qualities of life: Ordering concepts and measures of the good life. J of Happiness Studies. 2000; 1: 1-39.

- Alkire S, Foster J. Counting and multidimensional povertymeasurement. Journal of Public Economics. 2011; 95: 476-487.

- Hagerty MR, Cummins RA, Ferriss AL, Land K, Michalos AC, Peterson M, et al. Quality of life indexes for national policy: Review and agenda for research. Social Indicators Res. 2001; 55: 1-96.

- Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Marley AAJ. Best–worst scaling: Theory, methods and applications. Cambridge University Press. 2015.

- Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best–worst scaling: What it can do for health care research and how to do it. J of Health Economics. 2008; 26: 171-189.

- Thomas TW, Cankurt M. Evaluating the Role of Food Security in the Context of Quality of Life in Underserved Communities: The ISAC Approach. Nutrients. 2025; 17: 2521.

- WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995; 41: 1403-1409.

- Development of TheWorld Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998; 28: 551-558.

- Forgeard MJC, Jayawickreme E, Kern M, Seligman MEP. Doing the right thing: Measuring wellbeing for public policy. Int J Wellbeing. 2011; 1: 79-106.

- Bhandari S, Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Thorgerson A, Dawson AZ, Egede LE. Dose response relationship between food insecurity and quality of life in United States adults: 2016–2017. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2023; 21: 21.

- Lohr S. Sampling: Design and Analysis; Nelson Education: New York.2019.

- Rubin DB, Little RJA. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken. 2002.

- Cankurt M. A Study on the Determination of Farmers’ Demand for Tractor Satisfaction of Tractor Use and Purchasing Attitudes Towards Tractor: The Case of Ayd?n. 2009.

- Thompson B. The future of test validity. Educ Res. 2009; 38: 545-556.

- Thomas TW, Cankurt M. A multi-method Analysis of Food DesertResidents’ Lived Experience with Food. Med Res Arch. 2024; 12.

- Cankurt M, Miran B, Seyrek K, Sahin A, Everest B. Agricultural Reportof T22 Region, South Marmara Development Agency, Turkey. 2013.

- Saatchi R. Fuzzy Logic Concepts, Developments and Implementation. Information. 2024; 15: 656.

- Zhou L. Rules and Algorithms for Objective Construction of FuzzySets. 2024; 1.

- Trillas E, de Soto AR. On a New View of a Fuzzy Set. Trans Fuzzy SetsSyst. 2023; 2.

- Dutta B, García-Zamora D, Figueira JR, Martínez L. Building Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Membership Function: A Deck of Cards based Co- constructive Approach. 2025.

- Van Kooten GC, Schoney RA, Hayward KA. An alternative approach to the evaluation of goal hierarchies among farmers. Western J of Agricultural Economics. 1986; 11: 40-49.

- Liang D, Xu Z, Jamaldeen A. Fuzzy decision-making: Methods andapplications. Information Sciences. 2020; 512: 564-588.

- Chao X, Kou G. A group decision-making approach integrating preference analysis with fuzzy sets. Applied Soft Computing. 2021; 113: 107919.

- Xu Z, Liao H. A survey of preference modeling and decision analysis under fuzzy environments. Fuzzy Optimization and Decision Making. 2022; 21: 129-158.

- Górecki T, ?uczak M. On using nonparametric tests for multiple comparisons in ranking problems. Statistical Papers. 2021; 62: 2939-2963.

- Legendre P. A temporal beta-diversity index to identify sites that have changed in exceptional ways in space–time surveys. Ecology and Evolution. 2019; 9: 3500-3514.

- US Census Bureau. Demographic Characteristics in the United States. 2022.

- NC Office of State Budget and Management. North CarolinaDemographic. 2022.

- Data USA, North Carolina, Guilford County Statistics Data. 2022.

- Pew Research Center. National Statistics. 2022.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment Situation Summary. 2022.

- Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinicalimplications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012; 2012: 278730.

- Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Ory MG, et al. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging. 2003; 25: 327-365.

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review.1943; 50: 370-396.

- Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J of UrbanHealth. 2003; 80: 536-555.

- Powell LM, Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, Harper D. Availability of physical activity–related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: A national study. Am J of Public Health. 2007; 96: 1676-1680.

- Sampson RJ. Great American city: Chicago and the enduringneighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press. 2012.