Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Cells and Platelet Rich Plasma to Repair Rotator Cuff Injuries in Rats

- 1. Department of Orthopaedics Surgery, Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Rotator cuff injury is a common disease that may lead to persistent pain and functional impairment. Despite the improvement in the surgical technique, rotator cuff repairs are subject to a high rate of retears. A fibrovascular scar tissue is formed instead of true regenerative tissue. The use of biologic therapies could improve the healing of the tendon-to-bone insertion. We hypothesized that the combined use of adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) could improve the biomechanical and histological properties of the repair.

Material and Methods: A controlled experimental study conducted on 48 Sprague-Dawley rats. The supraspinatus tendon was sectioned and repaired and was randomly allocated to two groups: application of PRP alone or PRP and ASCs. Biomechanical and histological analysis was performed at 3 days, 1, 2 and 4 weeks.

Results: There were no statistically significant differences in the biomechanical study. In the PRP group, load to failure at two weeks was 3.89 N ± 0.99 and in the ASCs group was 7.87 N ± 2.18 (p=0.05). Histological examination showed an increase in the presence of vessels at one and four weeks in the ASCs group (p=0.047). Collagen fibers were present in 25% of the repaired tissue in the ASCs group at one week and absent in the PRP group (p=0.047). Maximum differences in collagen concentration occurred at two weeks in favor of the ASCs group (p=0.059).

Conclusion: The use of ASCs does not improve the biomechanical properties of the repair. However, increased vascularity and collagen fibers type I were promising findings in the group treated with ASC.

CITATION

Vadillo P (2022) Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Cells and Platelet Rich Plasma to Repair Rotator Cuff Injuries in Rats. Ann Sports Med Res 9(1): 1188.

INTRODUCTION

The estimated incidence of acute full thickness cuff tear is reported at 2.5 per 10000 patients aged 40-75 years [1]. Despite the improvement of the surgical techniques and implants rotator cuff repair is known to have a high failure rate after surgical repair [2,3].

Animal studies have shown that the four-zone tendon-tobone insertion is not recreated after surgical repair [3]. Instead, a fibrovascular scar tissue with poorer mechanical properties has been identified in its place. Hypothetically, recreation of the insertion site is critical for the restoration of tendon function and the prevention of retears. Several biologic strategies have been used to enhance the repair of the enthesis: bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) [4], fibroblast growth factor [5], the combination of different growth factors [6], inhibition of metalloproteases [7] or platelet rich plasma [8].

Adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ASCs) have shown to improve muscle function and decrease fatty infiltration after cuff repair [9], but alone they might be limited in restoring a complex area like the rotator cuff enthesis [10,11]. The addition of PRP could add potential biologic stimulus in the form of growth factors while providing a matrix that acts as a scaffold for the ASC.

We hypothesize that the local application of ASCs and PRP in a murine model of rotator cuff repair would improve the mechanical properties and histological findings of the tendon-tobone insertion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

This was a controlled laboratory study. We used 48 SpragueDawley rats under the guidelines of the Institutional Ethical Committee for Animal Welfare. We conducted a biomechanical study (n=24) and a histological analysis (n=24). In each group, the rats were divided into two groups: the PRP group (n=12) and the PRP and ASCs group (n=12). We performed a unilateral detachment and repair of the supraspinatus tendon with an intraosseous suture. According to the group of treatment, we added to the repaired tendon, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) or PRP with adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ASCs).

ASCs harvest and culture

ASCs were obtained from abdominal fat tissue of two rats according to a previously described protocol [10,11]. Briefly, the lipoaspirate was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and digested at 37°C for 30 minutes with collagenase (Type I; Gibco, Invitrogen). Enzymatic activity was neutralised by the addition of 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and the mixture was centrifuged at 300 g for 10 minutes. The cell pellet was washed and suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) plus 10% FBS. The resulting cell suspension from a further centrifugation cycle was filtered through a 70 μm nylon mesh. Lastly, the material obtained was resuspended in DMEM with glucose and pyruvate, 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1% streptomycin 10 m/ml and penicillin 1 UI/ ml. This product was named Stromal Vascular Fraction (SVF). The cells were then plated in 100-mm tissue-culture dishes at 10 to 15×103 cells/ml and cultured at 37°C in a humid atmosphere with 5% carbon dioxide in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, BRL). The medium was changed to remove non-adherent cells 24 hours after seeding, and every 4 days thereafter. For subculturing, cells were detached with 0.05% (v/v) trypsin in PBS when 70-80% confluence had been reached. Characterization studies were carried out by flow cytometry; the expression of the surface markers CD90, CD29, CD45, and CD11b were analyzed to confirm the mesenchymal stem cell phenotype of the cultured cells [12], after which the cells were cryopreserved with FBS and 10% DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide). Before surgery, the ASCs were thawed, cultured during 7-10 days and counted before implantation. 2 million ASCs were implanted per specimen.

PRP preparation

The technique to obtain PRP was described by Anitua [13, 14]. Blood was collected from two Sprague-Dawley rats. The rats were anesthetized using inhalatory isofluorane. Approximately 2 ml of blood were obtained from tail puncture of each rat. The blood was citrated and then centrifuged at 450 g for 10 minutes. The plasma fraction located just above the sedimented red cells but not including the buffy coat was collected. The PRP was divided in 35 μl and frozen at -20 ºC. Before implantation, the PRP was thawed, and 2.1 μl of calcium chloride was added to neutralize citrate and form a clot.

Surgical procedure

The surgical technique has been described before [10,11]. Animals were anesthetized with isofluorane. The side of the surgery was randomized in all cases. An anterolateral incision was performed in the front leg of the rat, and the deltoid was detached to expose the rotator cuff. We sectioned the supraspinatus tendon at the greater tuberosity and was acutely reinserted using a modified Masson stitch with a non-absorbable 5/0 suture through a tunnel in the proximal humerus. Before tying the knot a clot of PRP or PRP and ASCs, according to the group, was placed between the tendon and the bone. We reattached the deltoid using non-absorbable sutures and closed the skined with 3/0 silk sutures. Tramadol (5-10 mg/kg) was used for postoperative analgesia.

Histological study and biomechanical testing

The animals were euthanized at 3 days, 1, 2 and 4 weeks after surgery. For the histological study, we obtained the glenohumeral joint including the deltoid, humerus, and scapula. The specimens were fixed in 4% formalin, decalcified with EDTA during two weeks and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4 μm of the specimens were cut in the coronal plane. The slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome. An independent, blinded pathologist examined the tendon-tobone area. The presence of edema, vessels, inflammatory cells, fibroblasts, collagen fibers, and fibrocartilage was recorded on a scale of 0-3, 0 meaning the absence of the assessed parameter. The preparations were studied twice separated by a month.

When a discord between both readings was present, a third assessment was performed.

To assess the enthesis repair we used the Watkins score modified by Ide et al., [15]. To describe histological changes at the tendon-to-bone insertion on rotator cuff reconstruction.

Sacrificed times for the biomechanical study were 3 days, 1, 2 and 4 weeks after surgery. We dissected the shoulders to isolate the supraspinatus tendon, the humerus, and the scapula. The humerus was embedded in cement in 1 ml syringes (Palacos®, Zimmer). The specimens were frozen at – 80 ºC and thawed at room temperature for testing.

The biomechanical study was performed with a linear encoder with a sensor for position and two load cells of 20 N and 200 N (ControlTest®, Servosis, Madrid, Spain). The scapula and humerus were positioned so the tendon was alignment in the direction of its pull. The specimen was preloaded to 0.1 N and loaded to failure at a speed of 14 μm/s. We registered the information with the aid of a universal software, PCD-2K, designated for Windows to obtain a tension-deformation curve. The following data were recorded: load to failure (N), elastic load (N), deformation (mm), stiffness (N/mm2 ) and absorbed energy (J).

Statistical analysis

U Mann Whitney tests were used for intragroup and intergroup comparisons for the biomechanical study. A linear regression model was used to analyze the histological parameters. A standard statistical software was used for calculations (SPSS® version 15.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

All tendons failed in the repair site at the insertion in the humerus.

Biomechanical testing

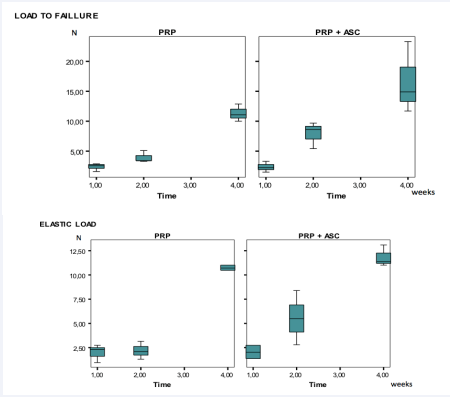

Load to failure and elastic load of the tendons increased with time in both groups.

Initially, both groups showed low resistance. At two weeks we observed differences between groups. In the PRP group, load to failure was 3.89 N ± 0.99 while in the ASC group it was 7.87 N ± 2.18 (p=0.05). At 4 weeks both groups became more homogeneous.

There were no statistical differences between the studied groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Specimens obtained by harvesting the scapula and humerus embedded in cement and prepared for the biomechnical study in a linear encoder machine.

Histological results

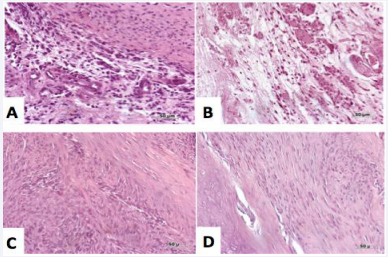

The tendon-to-bone insertion was not reproduced in any of the samples studied with or without cells. The repaired tendon formed initially a scarred, disorganized tissue, rich in cells, which turned to a more organized dense connective tissue at four weeks. Improved deposition of collagen-1 and fibrocartilage was observed in the ASC group at week 2, although this difference was not maintained at week 4.

Histological analysis

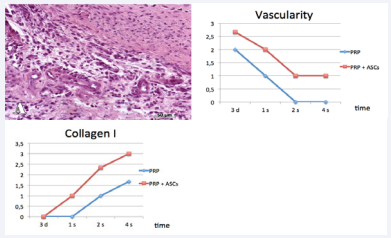

We observed an increased vascularity in the ASC group, being at one week two times more frequent in the ASC group (p=0.047). At four weeks, we identified sporadic vessels in the ASC group that were absent in the PRP group (p=0.047).

Figure 2: Biomechanical testing results. Three-day biomechanical testing was not included in the table.

Collagen concentration increased with time, being always more abundant in the ASC group. Collagen fibers were present in 25% of the repaired tissue in the ASC group at one week and absent in the PRP group (p=0.047). Maximum differences in collagen deposition were observed at two weeks, present in 25% of the preparations in the PRP group and 60% in the ASC group (p=0.059).

Using a linear regression model, we observed a stronger increase of collagen type I fibers in the ASC group over time when compared with the PRP group (0.799 vs. 0.503: p<0.001). Similarly, the fibrocartilage elevation was higher in the ASC group (0.786 vs. 0.097; p=0.119)

Watkins scale

The scores in the Watkins scale show an increase in tissue organization with time, peaking at week 2 (Table 1).

Table 1: Watkins scale results.

|

|

3 days |

1 week |

2 weeks |

4 weeks |

||||

|

Groups |

PRP |

ASC |

PRP |

ASC |

PRP |

ASC |

PRP |

ASC |

|

Score |

9 |

9.5 |

10 |

11 |

15.5 |

19.5 |

22 |

23 |

DISCUSSION

Failure of rotator cuff repairs is still very high despite the increase in the mechanical properties of modern suture techniques [16-18]. The absence of tissue regeneration of the tendon-to-bone insertion after rupture and surgical repair may be an influencing factor behind these results [2]. These facts have prompted an interest in developing different biologic therapies to augment rotator cuff healing [4-9,19-22].

Figure 3: Representative histological photographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained slides at 3 days (top row) and 4 weeks (bottom row). There is a modification from a disorganized tissue to a more organized dense connective tissue. (A) 3 days PRP; (B) 3 days PRP and ASCs; (C) 4 weeks PRP; (D) 4 weeks PRP and ASCs

The goal of biologic therapies is to improve the biologic environment around the repaired tendon to restore the histological structure of the native tendon-to-bone insertion and, hence, improve current biomechanical properties. Stem cellbased therapies are attractive because they provide a renewable source of pluripotent cells. They have been used extensively in experimental and clinical studies in several musculoskeletal diseases [9-11,19-24]. Our previous experience using ASCs in rotator cuff tears in rats [10,11]. have shown less inflammation and an increase in the elastic load. Similarly, Gulotta et al [20]. Showed no differences using bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the repair of the supraspinatus tendon. However, using MSCs transduced with scleraxis [21] increased the load to failure and the presence of fibrocartilage in the experimental group. Tissue-engineering strategies that use stem cells in combination with growth factors are under investigation. It may be possible that growth factors could improve the stem-cells environment by recruiting host cells, increasing vascularity or stimulating cell differentiation with modulation of the healing process.

Platelet-rich plasma is rich in growth factors and once clotted it can be used as a scaffold of the ASCs. In our study we used leucocyte-poor or pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) [25]to prevent inmune response reactions due to leucocytes and reduce scar formation.

The effect of PRP and MSCs has been proven in several in vitro studies, showing an increase in the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of MSCs using PRP as a cultured medium [26-29]. Chen et al [30]. Compared the use of phosphate-buffered saline, PRP, tendon stem cells and the combination of PRP and tendon stem cells in the repair of injured rat Achilles tendons and found higher levels of collagen I-mRNA in the PRP and tendon stem cells group. Uysal et al [31]. Compared the use of PRP and PRP + ASC in Achilles tendons of rabbits. At four weeks, the tensile strengths and collagen type I production was higher in the PRP + ASC group. Han et al demonstrated that the combination of MSCs and PRP promoted tendon-to-bone healing due to a stong angiogenesis, bone formation and tendon generation [32].

These data suggest that the combination of PRP and stem cells have synergic effects.

Figure 4: Evolution of the concentrations of vessels and collagen in the preparations

The objective of this study was to determine if the application of ASC and PRP in an animal model of acute rotator cuff repair would improve the histologic findings and the biomechanical characteristics of the repaired tendon.

Biomechanical data proved an increased load to failure in the group treated with ASC and PRP at two weeks (3.89 in the PRP group vs. 7.87 N in the PRP and ASCs group; p=0.05). Similarly, the elastic load at two weeks increased in the PRP + ASC group (2.16 N vs. 5.53; p=0.127). These differences decreased by week 4.

In the histological analysis, we observed an increased vascularity in the ASC group. Collagen concentration increased with time, being always more abundant in the ASC group. Collagen fibers were present already in 25% of the repaired tissue in the ASC group at one week and absent in the PRP group (p=0.047). Maximum differences occurred at two weeks, with the presence of collagen fibers in 25% of the preparations of the PRP group and 60% of the ASC group (p=0.059). Similarly, the results of the Watkins scale showed the most significant differences at two weeks, 11 in the PPR group and 15,5 in the combined group. At 3 days, one week and four weeks results were very similar between groups. Due to the biologic healing capabilities of the rat model that may lead to spontaneous healing we suggest two weeks as an appropriate timeline to study differences in both biomechanical and histological properties of a repaired rotator cuff in a murine model [33-34].

In our study, we did not find differences in the biomechanical properties of the tendon, but we observed histological advantages with the combined use of PRP and ASC [30]. The faster and more abundant presence of vascularity and collagen type I suggest a synergic effect between PRP and ASCs that may accelerate healing and is following similar findings in prior research [29].

The tendon-to-bone insertion was not reproduced in any of the samples studied with or without cells. The causes for this are likely multifactorial, and it is expected that several factors are necessary, in a timely and precise combination and concentration, to achieve optimal tendon healing and restoration of the enthesis. The simple application of growth factors will not predictably lead to the formation of a healthy tendon insertion site.

The present study has several limitations. First, we used an acute rat rotator cuff model that is different from the chronic degenerated tendon present in human rotator cuff tears. Although there are chronic models [34,35] this acute model has been widely used and accepted by the international community [3,5]. Because of the inability to immobilize the rat arm, the majority of the repaired tendons detach. The resulting gap fills in with scar tissue. Although an acute repair is performed, the tendon detachment and subsequent retraction mimic a chronic tear in humans [36]. We chose to analyze the animals at maximun 4 weeks. It is possible that we could have seen beneficial effects from the stem cells at later time points. We chose these early time points because previous authors had shown that tendons heal at 8-9 weeks [6,37]. In our study we have not included a formal control group (without ASCs and PRP). Our own prior experience [10,11]. Showed no advantage from the use of ASCs in rotator cuff in rats at different time points or with different carriers. However, the purpose of the present study was to determine if the addition of a biologic enhancer, as PRP to ASC, would stimulate the biologic response of ASCs alone in the restoration of the enthesis and create a more resistant tendon.

CONCLUSION

The use of ASC does not improve the biomechanical properties of the repair. However, histological analysis showed increased vascularity, and collagen fibers type I in the ASC group at two weeks suggesting a faster biological process. The complex interactions between stem cells and their biologic environment remains elusive and will need further investigation.