Aethoxysclerol Injections in the Treatment of Non-Insertional Achilles Tendinopathy: A Review

- 1. Department of Orthopaedics, St James’s Hospital, Ireland

ABSTRACT

Background: Achilles tendinopathy is a common, painful condition which can be difficult to treat. There are multiple non-operative and operative treatment options, with variable efficacy. Injection of aethoxysclerol is a relatively new treatment which has been used in recent years. The purpose of this literature review is to discuss the treatment in detail, and review the evidence for its efficacy.

Methods: We investigated all published randomised clinical trials and retroscpective studies pertaining to injection of aethoxysclerol for achilles tendinopathy.

Results: Overall, the evidence to date is conflicting. A number of studies have shown improved patient satisfaction following injection of aethoxysclerol. However, others conclude that there is no overall improvement.

Conclusion: Injection of aethoxysclerol for achilles tendinopathy is safe and well-tolerated, with good patient satisfaction. To date, it cannot be concluded whether the outcomes are indeed better than placebo treatment. As this treatment is still a relatively new method for treating this condition, there is scope for further studies to better ascertain its efficacy.

KEYWORDS

Achilles tendinopathy, Sclerosing agents, Aethoxysclerol/ polidocanol.

CITATION

Fhoghlu CN (2022) Aethoxysclerol Injections in the Treatment of Non-Insertional Achilles Tendinopathy: A Review. Ann Sports Med Res 9(2): 1191.

INTRODUCTION

Achilles tendinopathy is a painful condition affecting the achilles tendon, which may be acute or chronic. Patients complain of pain and swelling, as well as reduced performance abilities, often affecting normal activities of daily living. The condition is not very well understood. It is thought to be associated with overuse or excessive repetitive loading on the tendon [1]. Therefore it is commonly seen in athletes, and particularly runners. Other risk factors include increasing age, genetic predisposition, obesity and mechanical imbalance [2].

Achilles tendinopathy is generally categorised as insertional or non-insertional (mid-portion tendinopathy). Insertional tendinopathy is localised to the insertion point of the tendon on the posterior calaneus, while non-insertional tendinopathy occurs in the main body of the tendon. Histological studies of affected tendons reveal a predominantly non-inflamatory degenerative process with a disordered arrangement of inflammatory fibres and increased vascularity. Inflammation or tendinitis is not common [3].

In the normal achilles tendon, there is a region of relative hypovascularity 2 to 6 cm proximal to the insertion point. This correlates with the region where non-insertional tendinopathy occurs. It is hypothesised that this relatively impaired blood flow may impair healing ability [4]. While blood flow around the tendon increases during exercise, increased flow in this region may be lower than in the more distal tendon [5]. Furthermore, it has been shown in imaging studies that diseased tendons show areas of abnormal new vascularisation in the ventral mesotenal vessels in this zone. Targeting these areas of neovascularisation is the idea behind treatment with aethoxysclerol, the treatment of interest in this review.

Overview of currently available treatment options

Management of achilles tendinopathy can be difficult to treat, and as such there have been numerous treatment modalities attempted. These can be broadly divided into operative and nonoperative methods. Operative methods include percutaneous longitudinal tenotomies, ventral stripping of the tendon, and open excision of the diseased tissue. As these methods are invasive, they are generally reserved for cases that do not respond to conservative measures, approximately one-third of cases.

Simple non-operative interventions can be effective. Traditional methods include orthotics, stretching, heel lifts, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. A number of alternative interventions have been developed for cases which to not respond to these measures, with variable outcomes. These include corticosteroid injections, eccentric exercises, aprotinin injections, topical gylceryl trinatrate and extracoporeal shock wave therapy [6].

Use of peritendinous sclerosing injections (aethoxysclerol) is a futher, relatively new technique, which will be described in further detail.

Aethoxysclerol/ Polidocanol

Polidocanol was developed in 1931. It is a fatty alcohol, an ether derived from Lauryl alcohol. Originally it was used as a component in toiletries such as shamoo, hair conditioner, face creams and body lotions, and continues to be used in the manufacture of these products. In medicine it was first used as a local anaesthetic [7].

Polidocanol first began to be used for its sclerosing effect in the treatment of varicose veins. It has been shown to be safe, effective, and well tolerated. Reported side effects are uncommon; DVT, migraine, cutaneous necrosis, and in extremely rare cases, stroke [8,9]. Polidocanol exerts its sclerosing effect mainly by acting on the intima layer of the vascular wall. The mechanism of achion for this is through protein theft denaturation, whereby the polidocanol molecules form a lipid bilayer, causing disruption of the cell surface membrane, triggering pathways that lead to endothelial cell death [10]. Ultimately this leads to fibrosis of the vessel.

In 2002, Alfredson and Ohberg introduced aethoxysclerol injection as a new treatment for chronic achilles tendinopathy. As previously mentioned, their idea was based on the theory of neovascularisation in tendinopathy, with the aim of controlling this by sclerosing the aberrant vessels. Initial results were promising [11], and they have gone on to further develop this treatment with a number of published studies evaluating its efficacy.

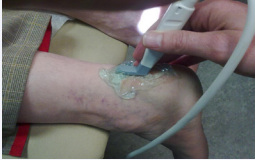

The injection is given using ultrasound (US) and colour doppler (CD) guidance, to identify the new vessels and target these with aethoxysclerol (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Position of the Ultrasound probe in relation to the tendon.

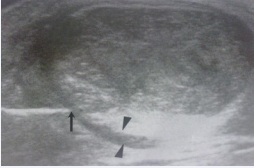

The needle is inserted medially (to avoid the sural nerve), and immediately deep to the tendon at the site of maximum hypervascularity (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The needle is inserted medially (arrow) and under direct ultrasound guidance placed immediately deep to tendon (arrowheads – epitendinous space).

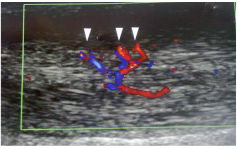

The area of neovascularisation is easily visible, and decreased vascularity is usually seen immediately, although the clinical response is usually delayed by several weeks Figure 3.

Figure 3: Area of maximum hyper vascularity (arrowheads).

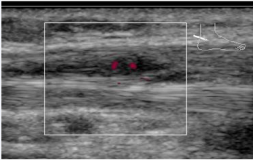

Figure 4.

Figure 4: Immediate reduction in vascularity seen following injection.

Evidence for the effectiveness of aethoxysclerol in achilles tendinopathy

The first randomised controlled trial investigating aethoxysclerol in achilles tendinopathy was published by Alfredson and Ohberg in 2005. This study compared injection of aethoxysclerol (polidocanol 5mg/ml) with injection of lidocaine 5mg/ml and adrenaline 5μg/ml [12]. There were 10 patients in each group. In both groups, initial treatment consisted of a maximum of two injections, and improvement was assessed by reported pain during and after tendon loading before and after treatment. This was assessed on a visual analogue scale for pain (VAS). Patients were also asked to report on overall satisfaction, either satisfied or not satisfied.

In the first treatment group (aethoxysclerol), following initial evaluation, there was a significant decrease in the mean reported pain during and after tendon loading. Mean VAS reduced from 77±7 before injection to 41±10 after (p<0.005). Furthermore, five patients reported satisfaction. Of the non-satisfied patients, all were offered further injections of aethoxysclerol (max two), and all were satisfied following this additional treatment.

In the second treatment group (lidocaine & adrenaline), the mean VAS did not reduce significantly after initial injections. No patient was satisfied with results. All non-satisfied patients were then offered aethoxysclerol treatment, and following this treatment (again, max two injections), there was a significant decrease in the mean VAS, 64±6 to 16±4 (p<0.005). Nine out of ten patients were satisfied with the results.

Interestingly, in this study, the changes to tendon neovascularisation were also assessed before and after treatment. Before treatment, all patients had documented neovascularisation on ultrasonography (US) and colour doppler (CD). In all cases where patients were satisfied with results, there was no remaining neo-vascularisation seen on repeat US and CD, whereas when patients were not satisfied, either following initial or final treatment, repeat US and CD showed remaining areas of neo-vascularisation.

Another randomised controlled trial comparing aethoxysclerol to lidocaine injection was recently published in 2017 [13]. In this study, higher doses of the injected agent were given, aethoxysclerol 10mg/ml in the first treatment group, and lidocaine 10mg/ml in the second treatment group. In the first group, the injection was repeated immediately if there was no coagulation of the vessels seen following initial injection. Both groups received a maximum of two treatments, the second being given only if US still showed areas of neovascularisation. There were 23 patients in the first treatment group (aethoxysclerol), and 21 in the second treatment group (lidocaine). Improvement in this study was determined by reported pain during walking, measeured on a VAS at 3 month follow-up. Two other scoring systems were used as secondary outcome measures, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS) and Victorian Institute of Sports Assessment-Achilles questionnaire (VISA-A).

At intial evaluation three months post treatment, there was a decrease in pain during walking, as measured by VAS, in the first treatment group (aexthoxysclerol), which was statistically significant (3.1 to 2.1). At six months, there was a very slight but non-significant further decrease in VAS (2.0). In the second treatment group (lidocaine), there was a non-significant decrease in VAS at three months (4.2 to 3.7). At six months, there was a further decrease which reached statistical significance (2.9). Notably, no significant differences were seen between the two treatment groups overall. At three and six month follow-up, the mean difference between the two groups was non-significant; 1.6 at three months, and 0.8 at 6 months. Therefore, while it can be seen that the actual reported VAS was lower in the aexthoxysclerol group, the findings did not reach statistical significance.

FAOS showed improvements in both groups, with a significant difference between the groups in favour of the aethoxysclerol group at three months, but no significant difference at six months. Similarly, the VISA-A score improved in both groups following treatment, but again there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Clementson et al. conducted a retrospective review of patients who underwent aethoxysclerol injections for achilles tendinopathy, reviewing a total of 25 patients over a 12 month period [14]. In this study, the dose of aethoxysclerol was 10mg/ ml. The treatment was repeated to a maximum of six times as necessary, with a four to six week gap between treatments. As in previous studies, neovascularisation around the tendon was confirmed on US and CD in all patients prior to treatment.

Overall, this study showed good results. Nine patients had no further symptoms of tendinopathy at follow-up. 10 showed improvement, such that they could return to their normal activity level. Two patients reported improvement, but could not return to their previous baseline activity level. Four of the 25 patients had no change in symptoms following treatment.

Another retrospective review was carried out in 2010, by van Sterkenburg et al [15]. There were 48 patients in this study, with 36 patients responding to follow-up questionnaires. Follow-up was at 6 weeks post treatment, and again sometime between 2.7 and 5.1 years. At 6 week follow-up, symptomatic patients were offered repeated injections, and the treatment was repeated to a maximum of five sessions. Again, treatment was offered only to patients with US & CD confirmed neovascularisation. Results at 6 weeks were measured in terms of self-reported pain level. Results at the second follow-up were measured by the same selfreported pain level, as well as VAS and VISA-A scores.

Results at 6 weeks showed that 44% of patients had pain relief, 42% reported no change in pain, while 14% had an increase in pain. At the time of midterm follow-up, 53% of patients had gone on to avail of alternative treatments, including surgical interventions. Of those patients who did not have any additional treatments, 69% had reported no complaints at 6 weeks followup.

It is worth stating that Alfredson et al., have published further studies on their technique, additional to the randomised controlled trial outlined above. Most notably, in 2006, they published a follow-up study showing 90% patient satisfaction at two years post-treatment [16]. In 2007, they conducted a study comparing aethoxysclerol injections with US & CD guided surgery (releasing the tendon from the ventral tissues). In this study six out of nine patients reported satisfaction 6 months after injection, while 10 out of 10 patients reported satisfaction 6 months after surgery [17].

Side Effects

In the studies outlined above, there were no reported adverse events in most patients. The treatment was well-tolerated in the vast majority of cases. There was one reported case of sural nerve paraesthesia and numbness.

In our unit, we have had one case of achilles rupture, which has not been previously reported. This was in a 78 year old lady who underwent two aethoxysclerol injections of 5mg/ml with a four week interval. Of note, her MRI prior to injection confirmed chronic tendinopathy, and also showed some cystic degeneration, and possible partial tearing [18]. We can only surmise that this cystic degeneration may have predisposed her to be at higher risk for rupture following injection.

DISCUSSION

The introduction of aethoxysclerol injections has been an exciting intervention in the management of achilles tendinopathy. Fundamentally, it is minimally invasive and well-tolerated, with few reported side effects. These characteristics make it a very acceptable treatment option.

Currently, the evidence for the efficacy of aethoxysclerol in achilles tendinopathy is conflicting. Alfredson et al., have consistently demonstrated good outcomes for their technique. However, it would seem that this has not been largely reproducible in other units. In particular, the randomised controlled trial by Ebbenson et al., has shed some doubt on the previously reported success of aethoxysclerol injections. Why there is such a discrepancy is not clear. Perhaps there may be an element of unintentional bias given that the outcomes are largely subjective, as they are based on patient self-reported responses. It is also true that all the studies referenced above contain relatively small patient numbers. A large systematic review of RCTs for tendinopathy injections, in 2017, concluded that aethoxysclerol, aprotinin, and platelet-rich plasma injections were no more effective than placebo for achilles tendinopathy [19]. As with this review of the literature, this systematic review was based on a small number of studies, and in fact included only one RCT specific to aethoxysclerol in achilles tendinopathy, namely the 2005 Alfredson et al. Paper, as this was the only published randomised controlled trial in this area at the time of their study. A 2015 Cochrane review on all injectable therapies for achilles tendinopathy (including aethoxysclerol), concluded that there is not sufficient evidence in the literature to draw conclusions on the use of any of these treatments [20].

In terms of addressing neovascularisation, aethoxysclerol is shown to be effective in reducing the number of pathological vessels. Alfredson et al., found that in patients who were asymptomatic following treatment, CD showed reduced neovascularisation versus those who remained symptomatic. Ebbenson et al also surmised that aethoxysclerol achieved a sclerosing effect, as the treatment was only repeated when neovascularisation remained on follow up US/CD, and fewer injections were required in the aethoxysclerol treatment arm of their study. However, whether the reduction in neovessels following injection correlated with symptomatic relief was not assessed. Van Stekenburg et al., found a moderate correlation between the amount of neovessels seen on US/CD and the pain level reported by the patient (r 5 0.48, P 5 .001).

Another potential confounder could be injection technique, which would be difficult to evaluate. The injection technique as described in the studies would appear to follow a fairly uniform method, whereby the sclerosant is injected under US and CD guidance at the ventral region of the tendon, targeting the areas of neovascularisation. In three of the four studies, the approach was from the medial side of the tendon to avoid damage to the sural nerve. In the one study where they approached from either side, depending on the area of most neovascularisation, there was one reported case of sural nerve paraesthesia, although the paper does not state whether in this case the injection was from the medial or lateral side.

With regards dosage, these studies used between 5mg/ml and 10mg/ml. A recent study in 2010 showed that there was no significant difference in terms of patient satisfaction, number of injections required or volume required when these two doses were compared [21]. Therefore we can surmise that dose would not have been a confounding factor in comparing these studies.

The use of aethoxysclerol in the management of achilles tendinopathy is still a relatively new technique, and naturally therefore, it is an area that requires further research. Certainly, it is evident from this review, that there is scope for further clinical studies to assess efficacy. Given that the side effect profile is low, it would be justifiable and valuable to conduct larger scale studies, to give a better indication as to the true effectiveness of this treatment. Overall, it can be concluded that it is safe and welltolerated, with good patient satisfaction. However, whether the outcomes are indeed better than placebo treatments is a question that we cannot sufficiently answer with the current evidence in the literature.