Beyond the Burn: How CBD Shapes the Post-Exercise Inflammatory Response

- 1. Associate Professor, Exercise Science, Western Kentucky University, USA

- 2. Clinical Assistant Professor, Marquette University, USA

- 3. PhD Student, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA

- 4. PhD Student, University of North Alabama, USA

Abstract

Resistance training (RT) induces skeletal muscle adaptations but is often accompanied by soreness and inflammation that may deter consistent participation. Cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychotropic cannabinoid with reported anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties, has gained popularity among athletes, yet limited evidence exists regarding its efficacy in exercise recovery. This study examined the effects of acute CBD supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation and muscle damage following a fatiguing RT protocol. Nine resistance-trained participants (7 males, 2 females) completed three randomized conditions: placebo, low-dose CBD (2 mg/kg), and high-dose CBD (10 mg/kg). Each trial consisted of eccentric back squats designed to induce delayed onset muscle soreness, with blood samples collected at baseline, 24, 48, and 72 hours post-exercise. Biomarkers analyzed included interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and myoglobin. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant effects of dosage or time for IL-6. For IL-10, there was a significant main effect of dosage and a dosage × time interaction, with lower concentrations observed in both CBD conditions compared to placebo. Myoglobin demonstrated a significant effect of time, but no effect of dosage or interaction. These findings suggest that CBD supplementation did not alter IL-6 or myoglobin responses but was associated with reduced IL-10 levels, potentially blunting the typical anti-inflammatory cascade following exercise. While CBD shows promise as a recovery aid in some contexts, its effects in healthy, resistance-trained individuals appear complex and context-dependent. Further research with larger, more diverse cohorts is warranted to clarify CBD’s role in exercise-induced inflammation and recovery.

Citation

Stone W, Tolusso D, Pacheco G, Barksdale M (2025) Beyond the Burn: How CBD Shapes the Post-Exercise Inflammatory Response. Ann Sports Med Res 12(1): 1235.

INTRODUCTION

Resistance training (RT), the intentional application of an external load to the body, is a proven strategy to enhance musculoskeletal strength, endurance, and power. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends that all individuals, including healthy and special populations, perform RT at least twice per week, emphasizing its role well beyond athletic performance [1]. Heavier training loads during RT deliver a potent anabolic stimulus, triggering prolonged muscle protein synthesis and fostering adaptations that support muscle hypertrophy, functional capacity, and long-term health. These benefits extend from competitive athletes seeking performance gains to older adults aiming to preserve independence and mobility. Notably, many of RT’s positive outcomes are linked to the controlled skeletal muscle damage it induces; this damage stimulates protein remodeling and repair. The magnitude of this remodeling process is closely tied to the extent of initial muscle disruption, underscoring the role of strategic mechanical loading in optimizing muscular adaptation. However, the muscle damage that sparks these adaptations is frequently accompanied by soreness and discomfort—factors that can deter individuals from applying the challenging loads essential for continued progress.

Cannabidiol (CBD) has been associated with analgesic effects as well as anti-inflammatory properties [2]. Unlike other cannabinoids found in the sativa plant, CBD has no psychotropic effects as it contains less than 0.3% THC. CBD has recently been approved to treat patients with epilepsy, symptoms of multiple sclerosis, and chronic pain. Although athletes self-report taking CBD to promote recovery and avoid muscular discomfort [3], very little information is available verifying the validity of these purported claims in humans. As such, the field is urging scientists to evaluate any potential beneficial effects of CBD on sport and RT related muscle soreness, including studies to establish an effective dose [4].

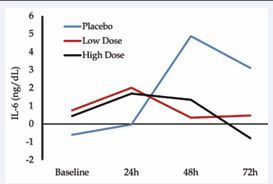

Our pilot study [5], evaluated RT and CBD in young adults (two male, two female). This randomized, double blind crossover design had participants completing the RT protocol under the administration of a placebo, low dose (2 ml/kg), and high dose (10 ml/kg) of CBD. Outcome variables included perceived pain, passive range of motion, performance (hand grip and bicep curl strength) and systemic inflammation (as measured by interleukin-6 (IL 6). Participants were subjected to six sets of ten eccentric squat repetitions, a protocol known to induce delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMs). Though no statistical significance was noted, we were encouraged by moderate to large effect sizes and CBD’s impact on inflammation (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Interleukin-6 response between placebo, low and high dose of CBD in pilot investigation [5].

Exercise is a relatively safe activity for most individuals, but it can be accompanied by uncomfortable side effects such as muscle soreness/fatigue, potentially causing avoidance behaviors [7]. Muscle soreness after exercise results from microtrauma to the muscular proteins, leading to inflammatory and immune reactions. This series of events is considered normal and important to the remodeling process, but individuals may take NSAIDs to counteract the discomfort. Consumption of NSAIDs post exercise, however, attenuates the protein remodeling necessary for muscular improvement [8]. Supplementing with CBD may serve as an alternative anti-inflammatory therapy that does not impair desired protein remodeling [2]. This may be of particular importance to athletes seeking a competitive edge as CBD is no longer a banned substance by the NCAA. Diminished soreness and increased recovery (by reducing inflammation) may allow individuals to train more frequently leading to greater overall volume of work (more positive adaptations).

Noting all of this, the purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the impact of CBD at two doses on the behavior of biomarkers of inflammation (IL-6 and IL-10) and muscle damage (myoglobin) after exhaustive RT. We hypothesized that CBD supplementation would positively impact biomarkers.

METHODS

Participants

An a priori power analysis using measures of effect from previous work [5] indicated a necessary sample size of nine individuals assuming a calculated f effect size of 0.5 (converted from np2 of 0.2) based on IL-6 response. Power was set to 80% and p < .05 as the benchmark for statistical significance in this three group (placebo, low, high), four measurement (baseline, 24, 48, 72hr) repeated measures, within-between interaction study design. Nine participants (M: 7 F: 2) were recruited, started and completed the investigation. To be included in the investigation, volunteers were required to have no recent history of cannabidiol or cannabis use (for at least two weeks preceding enrollment), be at least 18 years old and 110lbs. Participants could not be knowingly pregnant and were required to have a minimum exercise history of five years. Prior to data collection, participants signed an IRB approved informed consent. This study aligns with the ethical considerations outlined in Navalta et al., [6]. Participant demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Participant Descriptive Statistics

|

|

Total |

Males |

Females |

|

Age (yrs) |

20.5 + 1.9 |

21.3 + 1.8 |

19.0 + 1.0 |

|

Height (cms) |

172.2 + 10.2 |

178.3 + 6.5 |

160.5 + 5.1 |

|

Weight (kgs) |

71.5 + 13.4 |

78.7 + 10.0 |

59.1 + 7.0 |

|

Body Fat (%) |

14.7 + 6.9 |

9.6 + 4.0 |

23.1 + 2.4 |

|

Study Training Load (kgs) |

94.7 + 17.5 |

103.9 + 13.0 |

79.1 + 10.7 |

|

Average Low Dose (mg) |

142.4 + 29.1 |

161.0 + 19.3 |

118.3 + 14.0 |

|

Average High Dose (mg) |

712.0 + 145.3 |

805.0 + 96.2 |

591.1 + 69.6 |

Participants’ mass was determined using a calibrated scale and stature on a validated stadiometer. Body mass (in kgs) was used to prescribe load for resistance exercise and CBD prescription. Body composition was measured using three-site skinfold assessments, with locations for male participants at chest, abdomen, and thigh and females at triceps, suprailiac, and thigh.

Prior to exercise, two 4mL tubes of participants’ blood was collected by a phlebotomist. Processing of blood followed previously described methods [5]. In brief, samples were centrifuged for 12 minutes in their gel lithium heparin vacutainers. Plasma was separated from cells and stored at -80 degrees F until analysis. Analysis of blood samples were done in triplicate using immunometric assay for IL-6 (ELISA, High Sensitivity) IL-10 (High Sensitivity) and myoglobin following manufacturer guidelines (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts).

Supplementation followed the following scheme: 0 mg/ kg for placebo (or control), 2 mg/kg for low dose, and 10 mg/kg for high dose. CBD oil (Activ8) or placebo (soybean oil) was pipetted into vegan capsules designed to hold essential oils (XPRS Nutra, UT). Participants were given their supplementation according to their randomized assignment (randomizer.org) after blood draw and two hours before exercise. Participants consumed another dose no sooner than eight hours later.

The fatiguing protocol was designed to induce muscle soreness across a large portion of the body. Participants completed four sets of 60% body mass using eccentric focused back squats according to the following scheme:

- Set 1: Set to failure

- Set 2: Set to failure

- Set 3: Repeat number of reps from

- Set 2 Set 4: Repeat number of reps from Set 2

Failure was defined as the inability to (1) complete a repetition or (2) maintain the cadence prescribed for repetitions (four seconds eccentric, two seconds concentric) for two consecutive attempts.

Participants were given their second daily dose (to be taken no sooner than 8 hours) after completing the fatiguing protocol. They returned the next morning for another blood draw and to receive their daily doses. This process was repeated at hours 48 and 72. Participants completed a one-week washout between conditions.

Data Analysis

Separate 3x4 (dosage x time) repeated measures ANOVAs were employed to determine the effect of time and CBD dosage on biomarkers associated with inflammation following a fatiguing resistance protocol. Assumptions of sphericity were assessed using Mauchly’s test, with Greenhouse-Geisser corrections applied to the degrees of freedom when necessary. Normality of residuals was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests and visual inspection of QQ plots. If found to be violated, data were winsorized (within each dosage-time combination) and the assumption of normally distributed residuals was reassessed. When appropriate, post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni-corrected pairwise t-tests were performed for significant main effects. Statistical significance was set a priori at p ≤ 0.05. Effect sizes were reported as partial eta squared (ηp²). All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.4.2; R Core Team 2024) with the help of functions taken from the following packages: ez, emmeans, and car.

RESULTS

IL-6

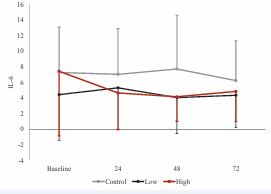

The ANOVA residuals were normally distributed both visually and according to the results of the Shapiro Wilk test (p = 0.41), meaning that winsorization of data was not necessary. However, Mauchly’s test indicated violations of sphericity for dosage, time, and the dosage X time interaction (p<0.05) and therefore, Greenhouse Geisser corrections were applied. The repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser corrections revealed no significant main effects of dosage, F1.27, 10.15 = 2.02, p = 0.186, ηp² = 0.04, time, F1.27, 10.18 = 0.58, p = 0.502, ηp² = 0.01, or dosage X time interaction, F2.25, 18.03 = 0.62, p = 0.569, ηp² = 0.02. (Figure 2).

Figure 2 IL-6 response across time and between conditions.

IL-10

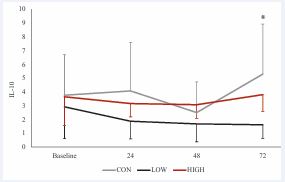

The ANOVA residuals showed slight deviations from normality (p = 0.013), with visual inspection of the QQ plots depicting residual outliers. Therefore, data were winsorized to address these violations and re-analyzed. Mauchly’s test indicated no violations of sphericity for dosage, time, or the dosage X time interaction (p > 0.05). Analysis of winsorized data revealed no significant effect for time F3, 24 = 1.83, p = 0.169, ηp² = 0.04. However, a significant main effect of dosage, F2, 16 = 10.46, p = 0.001, ηp² = 0.17, and a significant dosage X time interaction, F6, 48 = 3.14, p = 0.011, ηp² = 0.07. Post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction for the dosage main effect showed that IL-10 levels were significantly higher in the control condition compared to high dosage (p = 0.002) and low dosage conditions (p = 0.005), with no significant difference between high and low dosages (p = 1.00). (Figure 3).

Figure 3 IL-10 response across time and between conditions.

Myoglobin

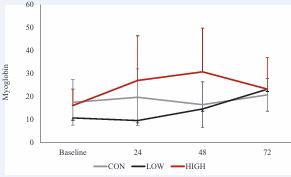

Results from the ANOVA demonstrated residuals were normally distributed (W = 0.98, p = 0.39), though visual inspection of residuals showed potential influential residuals. Given these potential violations of assumption of normality, data was winsorized and re-analyzed. Mauchly’s test indicated no violations of sphericity for dosage, time, or the dosage X time interaction (p > 0.05).

Analysis of winsorized data revealed a significant main effect of time, F3, 24 = 3.12, p = 0.045, ηp² = 0.06. However, no significant effect of dosage, F 2, 16 = 2.94, p = 0.082, ηp² = 0.11 or interaction of dosage X time were observed, F6, 48 = 1.83, p = 0.113, ηp² = 0.08. Post-hoc analyses revealed no significant differences between the control conditions and either the high low (p = 0.98) or high (p = 0.54) dosage conditions. Additionally, no differences were observed when comparing the high and low conditions (p = 0.08) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Myoglobin response across time and between conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the effects of two doses of CBD supplementation following a muscle-damaging back squat protocol, with inflammatory and recovery markers analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA. Results for myoglobin showed a significant main effect of time but no significant effects of dosage or the dosage × time interaction, and post hoc tests revealed no differences between conditions. In contrast, IL-10 analysis revealed a significant main effect of dosage and a significant dosage × time interaction, with post hoc tests indicating that IL 10 levels were significantly higher in the control condition compared to both CBD dosages, and no difference between the high and low CBD doses. For IL-6, no significant main effects or interactions were observed. Overall, while CBD supplementation did not influence myoglobin or IL-6 responses, both CBD doses were associated with lower IL 10 levels compared to the control condition.

Interleukin-6

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a complex cytokine that plays a dual role in the post-exercise response, functioning both as a pro-inflammatory mediator and as a myokine released from contracting skeletal muscle [9,10]. While not traditionally viewed as a primary biomarker of muscle damage, IL-6 is a rapid responder to metabolic stress [11], particularly glycogen depletion as could have been experienced in the current investigation but is more prominently elevated following endurance-type exercise [12]. Its early release serves multiple purposes: it mobilizes energy substrates, enhances fat metabolism, and initiates an acute-phase response by promoting neutrophil activity [8]. Importantly, IL-6 also stimulates the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL 1ra and IL-10, contributing to a homeostatic “rebound” effect post-exercise [12]. Thus, IL-6 acts as both a signal of physiological strain and a modulator of recovery, making it a key marker in understanding the inflammatory and metabolic adaptations to exercise.

Recent research highlights CBD as a promising modulator of exercise-induced inflammation, with multiple studies suggesting it can support recovery through both subjective and physiological pathways. Aswad (2025) demonstrated that while CBD does not always significantly blunt IL-6 levels post-exercise, it consistently shifts the cytokine profile toward a more anti-inflammatory balance, including increased IL-10, especially in individuals with higher baseline inflammation [13]. Similarly, Sermet et al., reported that CBD supplementation reduced IL-6 and IL-1β, suggesting that CBD may provide anti-inflammatory relief [14]. Rojas-Valverde (2023) corroborated these findings in a broader review, noting that although the effects on IL-6 in human exercise trials were inconsistent, largely due to variability in dosing and formulation, CBD generally reduced markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, without impairing training adaptations [15].

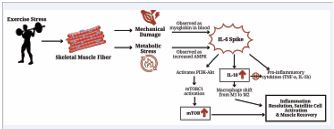

Mechanistically, the anti-inflammatory actions of CBD appear to result from a convergence of several pathways. Multiple research teams [13-15], report that CBD inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway, a central regulator of pro inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α. In addition, CBD exhibits antioxidant properties, reducing oxidative stress that would otherwise trigger cytokine release [14,15]. The compound also modulates immune activity via interactions with CB2 receptors on immune cells, TRPV1 channels, and adenosine receptors, contributing to both the suppression of pro-inflammatory signaling and promotion of anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10 and IL-1ra [13,14]. Collectively, these mechanisms contribute to reduced inflammation, enhanced immune regulation, and proposed improved recovery outcomes. While IL-6 responses to CBD remain inconsistent across human trials, likely due to variation in dosage and exercise protocols, the combined evidence suggests that CBD exerts multi-dimensional effects on inflammation with strong potential as a recovery aid for physically active individuals [15]. These mechanisms along with others are depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Visual representation of proposed mechanisms influencing biomarker response to damaging exercise.

Interleukin-10

IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, increased in circulation to dampen inflammation. It acts, in part, by inhibiting IL-1 and TNF-α production, thereby supporting recovery and immune regulation [16]. In the context of exercise, a transient rise in IL-10 (often occurring in parallel with IL-6) is thought to help prevent chronic inflammation following acute stress [17]. IL-6, produced by contracting skeletal muscle, may stimulate IL-10 release as part of an anti-inflammatory cascade that limits excessive immune activation and promotes tissue recovery [10]. This balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling is considered critical to avoid prolonged immune activation after strenuous exercise.

In the present study, CBD supplementation resulted in significantly lower circulating IL-10 concentrations compared to the control condition following a damaging back squat protocol. This contrasts with previous investigations in both animal and cell culture models, which have generally reported that CBD exerts anti inflammatory effects via increasing IL-10 expression alongside reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 [e.g., 18-20].

The discrepancy between our findings and prior CBD studies may relate to key differences in experimental design and physiological context. First, most studies reporting CBD-induced increases in IL-10 have used pre-clinical disease or injury models with high baseline inflammation, where an immunosuppressive effect of CBD may be more pronounced. In contrast, our participants were healthy and experienced transient, exercise-induced muscle damage, potentially eliciting a different regulatory pattern of cytokine production. Second, differences in CBD dose, delivery method, and timing relative to the inflammatory stimulus could alter immune modulation; pre-clinical models often use higher relative doses and more sustained administration compared to our acute supplementation protocol. Third, the exercise-specific immune environment may differ from pathological inflammation in terms of leukocyte infiltration, myokine signaling, and the magnitude of cytokine shifts, which could influence how CBD interacts with IL-10 regulatory pathways.

Taken together, while the literature suggests CBD can elevate IL-10 under certain conditions, our findings indicate that in the context of acute, exercise-induced inflammation in healthy individuals, CBD may blunt this anti-inflammatory cytokine response. This could represent a modulation of the IL-6 + IL-10 axis that, although potentially beneficial in chronic inflammation, may attenuate the typical recovery-oriented cytokine profile following strenuous exercise.

Myoglobin

In the present study, serum myoglobin concentrations increased in response to the damaging back squat protocol, consistent with previous literature identifying myoglobin as a sensitive biomarker of exercise-induced muscle damage [21]. However, no significant differences were observed between placebo, low-dose CBD, and high-dose CBD conditions across the recovery period. This finding contrasts with certain recent human trials reporting attenuated myoglobin responses following CBD supplementation, particularly after resistance exercise. For example, Isemann et al., found that an acute 60 mg dose of CBD reduced both myoglobin and dampened creatine kinase levels after high-volume resistance training, suggesting a possible protective effect on sarcolemma integrity [22]. Not all investigations, however, have demonstrated CBD-related reductions in myoglobin. A systematic review by Bezuglov et al., found that serum levels of myoglobin were typically higher in groups supplementing with CBD compared to placebo groups [23]. They argue that this could be due to participants feeling better during exercise and performing higher volumes during CBD supplementation.

Several factors may explain why our findings diverged from studies showing CBD-mediated reductions in myoglobin. CBD dosage, timing relative to exercise (pre exercise supplementation in the current study), and formulation (oil vs. capsule) vary widely across studies, and these parameters influence absorption kinetics and tissue availability [24]. Finally, our participants were healthy and resistance-trained, potentially displaying a blunted muscle damage biomarker response due to repeated-bout effects and enhanced membrane stability compared to untrained or clinical populations.

Overall, our results suggest that acute CBD supplementation at the doses tested does not meaningfully alter myoglobin kinetics during recovery from resistance exercise in trained individuals. This adds to a growing body of evidence that CBD’s effects on muscle damage markers are inconsistent across studies and may depend on exercise type, CBD formulation and dose, and participant training status.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 9) limits the statistical power and generalizability of the results, even though the study was adequately powered for medium-to-large effect sizes. Future research including larger, more diverse cohorts would strengthen confidence in the observed outcomes. Second, the participants were healthy, resistance trained young adults, which restricts the applicability of these findings to other populations such as older adults, sedentary individuals, or those with chronic health conditions. Third, while we employed a controlled dosing protocol, variability in CBD absorption and metabolism may have influenced the circulating concentrations and subsequent effects; future studies could benefit from pharmacokinetic monitoring or alternative delivery methods. Additionally, the study utilized a short-term supplementation design, and it remains unclear whether chronic CBD administration would elicit similar or divergent effects. Finally, the focus on specific biomarkers (IL-6, IL-10, and myoglobin) provided important insight into inflammation and muscle damage, but recovery is multifaceted, and inclusion of additional physiological, functional, and perceptual outcomes would offer a more comprehensive understanding of CBD’s role in exercise recovery.

CBD supplementation did not significantly alter myoglobin or IL-6 responses but was associated with lower IL-10 levels compared to control, suggesting a potential dampening of the anti-inflammatory cascade in healthy, resistance-trained participants. These findings highlight that CBD’s effects may differ between clinical/pathological inflammation and acute exercise-induced inflammation, and outcomes are highly dependent on context, dosing, and population studied.

REFERENCES

- American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- Atalay S, Jarocka-Karpowicz I, Skrzydlewska E. Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Cannabidiol. Antioxidants. 2020; 9: 21.

- Kasper AM, Sparks SA, Hooks M, Skeer M, Webb B, Nia H, et al. High Prevalence of Cannabidiol Use Within Male Professional Rugby Union and League Players: A Quest for Pain Relief and Enhanced Recovery. Int J Sport Nutr Exercise Metabolism. 2020; 30: 315-322.

- Close G, Gillham S, Kasper A. Cannabidiol (CBD) and the athlete: claims, evidence, prevalence and safety concerns. Gatorade Sports Science Institute. 2022.

- Stone WJ, Tolusso DV, Pancheco G, Brgoch S, Nguyen VT. A Pilot Study on Cannabidiol (CBD) and Eccentric Exercise: Impact on Inflammation, Performance, and Pain. Int J Exerc Sci. 2023; 16: 109- 117.

- Navalta JW, Stone WJ, Lyons TS. Ethical Issues Relating to Scientific Discovery in Exercise Science. Int J Exerc Sci. 2020; 12: 1-8.

- Claudio Nigg. Barriers to exercise behavior among older adults: afocus-group study. J Aging Phys Act. 2005; 13: 22-23.

- Trappe TA, White F, Lambert CP, Cesar D, Hellerstein M, Evans WJ. Effect of ibuprofen and acetaminophen on postexercise muscle protein synthesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002; 282: E551-E556

- Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Asp S, Schjerling P, Pedersen BK. Pro- and anti- inflammatory cytokine balance in strenuous exercise in humans. J Physiol. 1999; 515: 287-291.

- Calle MC, Fernandez ML. Effects of resistance training on cytokines. Nutrients. 2021; 13: 1902.

- Calle MC, Fernandez ML, McCormick R, Martins C. Effect of exercise under hot conditions on inflammatory markers, myoglobin and post- exercise hemodynamics. J Sports Sci Med. 2016; 15: 62-69.

- Katsuhiko Suzuki. Cytokine response to exercise and its modulation. Antioxidants. 2018; 7: 17.

- Aswad M, Pechkovsky A, Ghanayiem N, Hamza H, Louria-Hayon I. High CBD extract (CBD-X) modulates inflammation and immune cell activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2025; 16: 1599109.

- Sermet S, Li J, Bach A, Crawford RB, Kaminski NE. Cannabidiol selectively modulates interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-6 production in toll-like receptor activated human peripheral blood monocytes. Toxicology. 2021; 464: 153016.

- Rojas-Valverde D, Fallas-Campos A. Cannabidiol in sports: insights on how CBD could improve performance and recovery. Front Pharmacol. 2023; 14: 1210202.

- Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM. IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol. 2008; 180: 5771-5777.

- Steensberg A. IL-6 induces IL-1ra and IL-10 production in humans. J Physiol. 2003; 547: 633-639.

- Burstein S. Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: a review of their effectson inflammation. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015; 23: 1377-1385.

- Nichols JM, Kaplan BLF. Immune Responses Regulated by Cannabidiol.Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020; 5: 12-31.

- Vu?kovi? S, Srebro D, Vujovi? KS, Vu?eti? ?, Prostran M. Cannabinoidsand Pain: New Insights from Old Molecules. Front Pharmacol. 2018; 9: 1259.

- Peake JM, Suzuki K, Wilson G, Hordern M, Nosaka K, Mackinnon L, et al. Exercise-induced muscle damage, plasma cytokines, and markers of neutrophil activation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005; 37: 737-745.

- Isenmann E, Veit S, Starke L, Flenker U, Diel P. Effects of Cannabidiol Supplementation on Skeletal Muscle Regeneration after Intensive Resistance Training. Nutrients. 2021; 13: 3028.

- Bezuglov E, Achkasov E, Rudiakova E, Shurygin V, Malyakin G, Svistunov D, et al. The Effect of Cannabidiol on Performance and Post- Load Recovery among Healthy and Physically Active Individuals: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16: 2840.

- Millar SA, Stone NL, Yates AS, O’Sullivan SE. A Systematic Review on the Pharmacokinetics of Cannabidiol in Humans. Front Pharmacol. 2018; 9: 1365.