Contributions of the Northern Traditional Leaders to the 2017 or 2018 Measles Vaccination Campaign in the Northern States of Nigeria

- 1. National Primary Health Care Development Agency, Abuja, Nigeria

- 2. African Field Epidemiology Network, Nigeria

- 3. World Health Organization, Country Office, Abuja, Nigeria

- 4. Technical Assistance Consultant, Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, Switzerland

- 5. Nigeria Governors Forum, Abuja, Nigeria

- 6. UNICEF Nigeria Country Office, Nigeria

Abstract

Introduction: Traditional Leaders are known to be relevant stakeholders as they demonstrate remarkable authority through which political and religious leaders reach out to the members of a given community. Traditional Leaders resolve disputes and enforce government directives on their subjects, leading to peace and stability with enhanced community involvement at addressing community needs. We reviewed the 2017/2018 MVC (Measles Vaccination Campaign) data to demonstrates the impact of the Northern Traditional Leaders’ support to the campaign in the northern states of Nigeria Methods: We reviewed all documents linked to the Northern Traditional Leaders Committee (NTLC) activities, during the 2017/2018 measles vaccination exercise in the northern part of Nigeria. The documents information included notes of the meetings held with the Leaders, collation of the signed engagement, documentation that involved their physical presence either at the flag-off, during the evening review meetings and in resolving conflicts in their respective communities as well as direct involvement in the campaign supervision. Results: All the 20 states of the North participated in advocacy and sensitisation meetings at their various states, but only four (20%) followed up with their states to release counterpart funds. The NTL chaired 15 (75%) of all the 20 Northern states, 2017/2018 MVC flag-off ceremonies that were conducted at the states. Overall, the northern States recorded an average vaccination coverage of 88.2% during the 2017/2018 MVC. Twelve (60%) of the northern states recorded vaccination coverages of ≥90%. Conclusion: The impact of Traditional Leaders involvement in the 2017/2018 MVC is evident by the remarkable difference in the number of children reached with the vaccine in the northern states of Nigeria. For the first time in measles vaccination campaigns in Nigeria, a special presentation was made to the Northern Traditional Leaders with special task for their support during the campaign. Their influence at each level of decision making and in the patriarchal society of northern Nigeria provides a trusted platform for directly engaging them on important issues, including primary health care services in the country.

Keywords

Advocacy; Sensitization; Traditional leaders; Caregivers

Citation

Kariya S, Oteri AJ, Taiwo L, Bawa S, Asolo J, et al. (2022) Contributions of the Northern Traditional Leaders to the 2017/2018 Measles Vaccination Campaign in the Northern States of Nigeria. Ann Vaccines Immunization 6(1): 1020

INTRODUCTION

The role of Traditional Leaders in modern Africa is either “traditionalists” or “modernists.” Traditionalists regard Africa’s traditional chiefs and elders as the true representatives of their people, accessible, respected, and legitimate, and therefore still essential to politics on the continent [1]. Traditional Leaders are essential stakeholders that demonstrate remarkable authority through which political and religious leaders reach out to the members of a given community [2,3]. Traditional Leaders have a portfolio based on a hierarchy with the most senior leaders being influential at the state level, while others exercise authority at Local Government, District, ward or community levels [4]. The use of Traditional Leaders to resolve disputes and enforce government directives on their subjects has proven to be a powerful method for peace and stability with enhanced community involvement in addressing community needs [5]. On the other hand, modernist are leaders known for embracing new ideas, styles, and social trends. For them, traditional values were chains that restricted both individual freedom and the pursuit of happiness. They view traditional authority “as a gerontocratic, chauvinistic, authoritarian and increasingly irrelevant form of rule that is antithetical to democracy” [6] Traditional Leaders are community leaders in Nigeria; they include Emirs, Chiefs, District, Village and Ward Heads who serve as the gatekeepers to every community who enjoy a high-level of voluntary reverence from their subjects [1,5,7]. Traditional Leaders wield so much influence within their business community where they play significant roles in ensuring the overall wellbeing of their community members [5,8]. By way of definition, Emir is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of highranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or ceremonial authority. The title has a long history of use in the Arab World, East Africa, West Africa, Afghanistan, and the Indian subcontinent. In the modern era, when used as a formal monarchical title, it is roughly synonymous with “prince“, applicable both to a son of a hereditary monarch, and to a reigning monarch of a sovereign principality, namely an emirate. In most of the northern states in Nigeria, the title of Emir is used to qualify the paramount traditional ruler however some of the northern states also adopt the title in their native languages such as “Shehu of Borno, Gbong Gwom Jos, Tor Tiv of Benue, Attah of Igala, Etsu of Nupe, Lamido of Adamawa, Aku Uka of Taraba” amongst notable paramount traditional rulers in northern Nigeria [9]. The Chiefs administer traditional leadership to a defined tribe and culture within a chiefdom, in a state and usually recognized in the southern part of Nigeria as paramount traditional leaders. The Nigerian Chieftaincy consist of everything from the country’s monarchs to its titled family elders, the chieftaincy as a whole is one of the oldest continuously existing institutions in Nigeria while the district, village and ward leaders administer traditional leadership at the district, village and ward levels in Nigeria [10]. Supplemental immunisation activities (SIAs) are conducted to boost suboptimal routine immunisation (RI) coverage and a set post campaign coverage survey result is fixed to attain herd immunity. For measles vaccination campaign, 95% coverage is advocated to attain a reasonable herd immunity to break the chain of disease transmission [11]. Learning from the polio SIAs experience, the National Measles Technical Coordinating Committee (NMTCC) solicited for the support of the Northern Traditional Leaders’ Committee (NTLC) on Primary Health Care Service Delivery considering their positive influence and unitary structure in the country [2,12]. The NTLC was inaugurated on 15th June 2009 to deliberate on the Polio Eradication Initiative (PEI) and Primary Health Care (PHC) situation in Northern Nigeria. The NTLC had played critical roles in increasing vaccine acceptance for polio through robust social mobilisation activities and they have been critical to reaching all eligible children with the polio vaccine, especially in northern Nigeria [13]. To facilitate their activities and make maximum impact, they have established committees at the national, state, Local Government Areas (LGAs), wards and settlements. These committees are involved in advocacy, vaccination microplanning, vaccination team selection, supervision of vaccination activities, resolution of vaccine hesitancy and promotion of community demand for vaccination services [14]. Leveraging on the role of the Northern Traditional Leaders Committee on the PEI, NMTCC committed the NTLC to supporting the mobilisation of their respective community members to ensure all eligible children targeted for the 2017/2018 measles vaccination campaign (MVC) were vaccinated. The collaboration of the government with the Traditional Leaders over the years has proven to be a useful entry point to strengthen Primary Health Care (PHC) services in Nigeria [5,15,16]. This paper describes the role and the impact of the Northern Traditional Leaders’ support to the 2017/2018 MVC conducted in the 19 northern states and the Federal Capital Territory.

METHODS

Setting This is a descriptive study of the role of the NTLC during the 2017/2018 MVC in 19 northern states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria. Procedures To enhance the quality of the 2017/2018 MVC and ensure the achievement of the programme target of 95% vaccination coverage, the National Measles Technical Coordinating Committee (NMTCC) was set up by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA). The NMTCC is a team made up of government and partner representatives with the secretariat at the NPHCDA and responsible for the planning and implementing measles vaccination campaigns in Nigeria [17]. The NMTCC engaged the NTLC and solicited for their support and spelt out expected roles they need to play in order to ensure that every eligible child in their jurisdiction targeted for vaccination during the 2017/2018 MVC is reached and vaccinated. The NMTCC structure is replicated in the states as the State Measles Technical Coordinating Committee (SMTCC), headed by either the Commissioner for Health or the Executive Secretary of State Primary Health Care Boards – (SPHCDB). The SMTCC carried out follow up advocacy with the respective Chairmen of the State council of Traditional Leaders. Specific roles and responsibilities of Northern Traditional Leaders during 2017/2018 MVC The underlisted roles were outlined for the NTLC during the engagement between NMTCC and the NTLC prior to the commencement of the 2017/2018 MVC: i. Sensitised members of their communities about the measles vaccination campaign. ii. Encouraged caregivers to bring their children for vaccination through community engagement meetings. iii. Sensitised caregivers on the importance of the measles vaccination through exhortation at gatherings or in mosques and churches. iv. Ensured their ward/village/district heads supported the campaign by identifying house to house community mobilisers who tracked, and line listed all eligible children and provided detailed feedback beforethe implementation of the vaccination exercise. v. Mobilised traditional and religious leaders in the wards/ settlements toparticipate in the microplanning processes and other preparatory activities before implementation. vi. Supervised the vaccination process and ensured orderliness during the vaccination process. vii. Assist with advocacy to the state Governors to release their state counterpart funds which was necessary for activities not funded by Gavi such as logistics for extra teams, additional mop up days needed for good coverage and quality of the MVC. Review of NTLC Activities during 2017/2018 MVC We conducted a desk review of all the information linked from the NTLC meetings up to the implementation of the measles vaccination exercise during the 2017/18MVC in the northern part of Nigeria. This information included meetings held with the Leaders, collation of the signed engagement, documentation that involved their physical presence either at the flag-off, during the evening review meetings and in resolving conflicts, or vaccine hesitancy (i.e., non-compliance with vaccination) in their respective communities. During the 2017/2018 MVC national, state and local government and ward level teams received a lot of support from the NTLC.The following examples describe the contribution of NTLC to the 2017/2018 MVC. Advocacy/Sensitisation meetings with Traditional Leaders at various levels Before the 2017/2018 MVC campaign, several meetings were held with the Traditional Leaders at the national, state, LGA and ward levels to solicit their support and cooperation towards a successful MVC. Advocacy and sensitisation to the Traditional Leaders were done to intimate them on the planned activities and their roles towards a successful measles campaign. Advocacy visits were made to Emirs and Chiefs (NTLC) to solicit their support in creating community awareness and mobilisation. States and LGAs held sensitisation meetings for Traditional Leaders alongside media and Religious Leaders before the campaign preparatory activities such as micro planning and training of vaccination teams.This process was initiated when the chairman NMTCC paid a high-level advocacy visit to the NTLC in July 2017. This was replicated at the sub national levels. ii. Flag-offs conducted by Traditional Leaders in the northern States: Traditional Leaders mobilised and participated actively in the 2017/2018 MVC flag-off in all the northern States. Flag-off activity is a formal declaration of the start of implementation of the campaign where key stakeholders such as traditional, political and religious leaders as well as Partner Agencies declare their commitment for the campaign. It is at the flagoff that Traditional leaders express their support, give community ownership commitment for the campaign and witness the actual vaccination of eligible children. iii. Mobilisation of communities/clients, supervision of vaccination process and resolution of noncompliance by Traditional Leaders during the campaign: Documented report by ward and LGA level immunisation task force showed that during the 2017/2018 MVC traditional and religious leaders engaged in community mobilisation and convinced caregivers to take eligible children to vaccination posts. They provided an excellent interface between the vaccination teams and their communities and played essential roles in creating awareness in and changing wrong perceptions of caregivers towards measles vaccination. They actively participated in the selection of house to house mobilisers who line listed children within their catchment areas and also ensured that all the linelisted eligible children were vaccinated during the campaign. The house to house mobilisers give feedback to the Traditional leaders since they were selected or nominated by them.

DATA SOURCES

We reviewed data from the end process monitoring checklist of the 2017/2018 MVC, the 2015/2016 and the 2017/2018 post-campaign coverage survey data; this was analysed using Microsoft Excel. We also reviewed minutes of NTLC meetings at the national level; reports of sensitisation and dialogue meetings held with traditional leaders in the States, LGAs and ward levels.

RESULTS

The NMTCC engaged NTLC at the national level in July 2017. All the 20 states of the North participated in advocacy and sensitisation meetings at their various states, only 4 (20%) followed up with their states to release counterpart funds (Table 1).

| Table 1: Advocacy and Sensitization Meetings with NTLC. | |

| Activities | Outcome |

| National level NTLC workshop | National NTLC sensitised on 2017/2018 MVC July 2017 |

| Advocacy/Sensitization of NTLC at State, LGA & Ward levels | 20 States, August 2017 |

| Involvement in the release of State Counterpart fund | Sokoto, Jigawa, Plateau & Katsina |

The northern Traditional Leaders chaired 75% of all 2017/2018 MVC flag-off ceremonies that were conducted at the state, LGA and wards levels in 20 northern states. Of the 20 states, three (15%) states had a flag-off at the state and LGA levels only, 13 (65%) had flag-off ceremonies at all levels, while four (20%) did not have flag-off supported by the Traditional Leaders (Table 2).

| Table 2: 2017/2018 MVC Flag-offs conducted by traditional leaders in the northern States | |||

| Activities | States | No. | % |

| Flag-off ceremonies at all levels | FCT (Abuja), Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Nasarawa, Niger, Plateau, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara | 13 | 65 |

| Flag-off at the state and LGA levels only | Borno, Kogi and Taraba | 3 | 15 |

| Did not have flag-off supported by the Traditional leaders based on no report | Adamawa, Bauchi, Benue and Kwara | 4 | 20 |

| Total | 20 | 100 | |

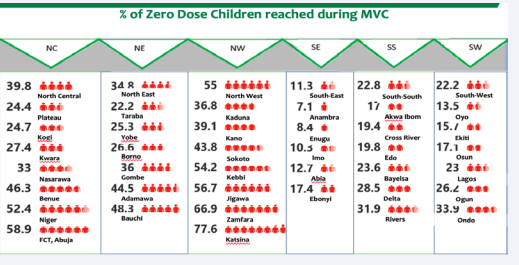

Twelve (60%) of the northern states recorded vaccination coverages of 90% and above, with FCT scoring 98.3% in the post campaign coverage survey. In terms of zero dose children reached during the 2017/2018 MVC, the Northern states had more compared to their southern counterparts as shown by the post campaign coverage survey report with states in the North West zone having the highest and South East states the lowest Figure 2 [18].

Figure 2: Percentage of zero dose children reached during the 2017/2018 MVC from the PCCS

Overall, the northern states recorded an average vaccination coverage of 88.2% during the 2017/2018 MVC (Table 3).

| Table 3: State specific End Process Data (Admin coverage) by Sources of Information during 2017/2018 MVC, Nigeria. | ||||||||||||||

| States | Total number of Sources of Information | Tradiional* Instittions | Radio | TV | Religious Leader | Neighbor, Friend | Celebrity | Film/Theatre show | SMS | Health Worker | Other sources | Not aware of campaign | Admin. Coverage | |

| Adamawa | 4,319 | 84.5 | 3.9 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 104.2 | |

| Bauchi | 5,279 | 83.4 | 7.1 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 108.6 | |

| Benue | 9,742 | 61.3 | 6.4 | 1.0 | 21.1 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 114.0 | |

| Borno | 8,254 | 70.9 | 9.2 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 96.6 | |

| FCT, Abuja | 2,970 | 49.4 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21.3 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 113.3 | |

| Gombe | 2,640 | 62.3 | 11.9 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 13.4 | 0.2 | 107.5 | |

| Jigawa | 11,233 | 89.4 | 2.2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 100.9 | |

| Kaduna | 20,193 | 61.3 | 13.8 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 6.3 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 104.9 | |

| Kano | 13,782 | 69.8 | 18.4 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 4.7 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 102.5 | |

| Katsina | 24,297 | 75.8 | 9.6 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 107.2 | |

| Kebbi | 4,578 | 82.0 | 7.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 0.2 | 113.0 | |

| Kogi | 12,078 | 51.7 | 11.6 | 3.2 | 7.1 | 5.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 18.8 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 126.4 | |

| Kwara | 5,567 | 58.6 | 6.6 | 1.4 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 15.1 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 104.2 | |

| Nasarawa | 4,799 | 78.0 | 3.5 | 0.2 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 6.6 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 109.8 | |

| Niger | 8,974 | 74.6 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 10.3 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 129.4 | |

| Plateau | 6,600 | 65.7 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 14.8 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 102.5 | |

| Sokoto | 8,497 | 82.3 | 8.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 104.0 | |

| Taraba | 6,105 | 73.9 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 10.9 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 107.2 | |

| Yobe | 6,075 | 83.7 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 101.4 | |

| Zamfara | 5,035 | 71.7 | 18.8 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 110.6 | |

| Total | 171,017 | 68.6 | 8.6 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 6.8 | 2.3 | 0.8 | 106.8 | |

| *Made up of Traditional Leaders, Town criers and Community dialogue | ||||||||||||||

| Table 3b: Zonal End Process Data (Admin coverage) by Sources of Information during 2017/2018 MVC, Nigeria | ||||||||||||

| Zones | Total number of Sources of Information | Tradiional* Instittions | Radio | TV | Religious Leader | Neighbor, Friend | Celebrity | Film/Theatre show | SMS | Health Worker | Other sources | Not aware of campaign |

| NC | 50,730 | 62.5 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 9.8 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 11.8 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| NE | 32,672 | 77.0 | 5.7 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| NW | 87,615 | 74.0 | 11.3 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 0.6 |

| SE | 36,476 | 46.2 | 9.7 | 1.7 | 13.1 | 7.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 19.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| SS | 50,398 | 39.3 | 13.2 | 4.6 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 20.8 | 4.2 | 0.8 |

| SW | 43,236 | 39.6 | 17.7 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 19.5 | 3.9 | 1.0 |

| Total | 301,127 | 58.3 | 10.9 | 2.8 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 12.6 | 2.7 | 0.9 |

| *Made up of Traditional Leaders, Town criers and Community dialogue | ||||||||||||

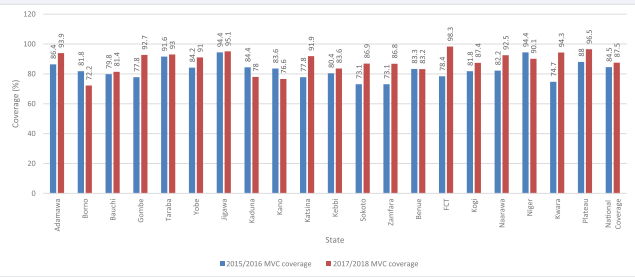

Fifteen (75%) of the 20 northern states had a higher vaccination coverage during the 2017/2018 MVC when compared with 2015/2016 MVC post campaign coverage survey [19]. Five states of Borno,Niger, Kaduna, Benue and Kano had higher coverages in 2015/2016 MVC than in 2017/2018 MVC. Benue recorded near equal coverages of 83.3% and 83.2% in 2015/2016 MVC and 2017/2018 MVC, respectively (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Our review showed that Traditional Leaders were effective in community engagement, awareness and demand creation for (Figure 1).

Figure 1: State comparison between 2015/2016 MVC and 2017/2018 Measles Vaccination Campaign

effective SIA performance as evidenced by the increased number of target children reached during the 2017/2018 MVC as well as the number of zero dose children reached during the campaign which in literary terms explains the ability of the campaign to have an impact on the coverage. This finding is similar to the report from the polio program, as shown in studies conducted by Nwaze et al., in their evaluation of the engagement of traditional and religious leaders in Nigeria. Majority of the respondents spoke of their positive involvement in the polio program and advocated for the systematic engagement of the Traditional and religious leaders in vaccination programs. Similarly, Oyo-Ita et al., sees the traditional and religious leades as untapped resources in the community to boost routine immunisation in their study on engaging communities in decision-making and action through traditional and religious leaders on vaccination coverage in Cross River State, Nigeria [20-23]. Benefits from the proactive nature of these traditional leaders fight against Polio in northern Nigeria cannot be downplayed and promising for engagement in the effort to reduce maternal and child mortality rates, which currently rank higher in the north when compared to the south likely due to the higher number of immunization incompleteness in the north [24]. Due to their active role and ability to speak directly to even the hardest-toreach, the 2017/2018 MVC leveraged on the polio structure to engage Traditional Leaders as the first point of entry into the communities [5]. The Emirs, Chiefs, District, Village and Ward Heads, exercise considerable influence in their communities. They are heads of the traditional system, hence arbitrate and supervise development programs in their areas of jurisdiction. Our review established that Traditional Leaders contributed significantly to the success of the 2017/2018 MVC by soliciting community support and cooperation for implementing the program. This is similar to findings by Koanane in South Africa in 2018, who found that Traditional leaders play a significant role in governance and Bakamana 2021 that sees them as complements to contemporary governance [25,26]. Walsh et al., also reported that the Traditional Leaders played a pivotal role in MNCH service utilization by mobilizing the communities during MNCH campaigns and activities [3]. We found that the Traditional Leaders’ contribution to awareness during the 2017/2018 MVC was extremely significant as end process monitoring data showed that 58.8% (Town criers, community dialogues conducted by the community traditional leaders and direct Traditional leaders) of all sources of information to caregivers was through the traditional institution.This finding further corroborates the findings in separate studies by Walsh et al. in Malawi, 2018 and Evelyn et al., in southern Ghana, 2014 who confirmed that Traditional Leaders play a significant role at involving communities in government interventions at the ward levels [3,27].The traditional institution supported the campaign by conducting supervision of vaccination teams, debunked antiimmunisation rumours, resolved non-compliance and identified missed children within their communities with the feedback from community mobilisers.The presence and leadership of Traditional Leaders in supervision and evening review meetings enhanced the ability to resolve issues quickly. Some of the Traditional Leaders hosted the evening review meetings, thus showing ownership of the campaign. This is consistent with the suggestions of Davidson M. in 2012, asking for a strong involvement of community and the traditional leaders in Nigeria being the catalyst for change in the country’s polio eradication efforts. This they responded by their involvement in microplanning processes which improved the identification of vulnerable children, thereby reducing the chances of missing children during the campaigns [28]. Our review revealed that there was an increase in the performance of the northern states during 2017/2018 MVC compared to the previous campaign. The target set for each state was 95% coverage, and although only three (15%) of the states reached the specified vaccination coverage target, the majority of the states had vaccination coverage of ≥90% with an average of 88.2%. This increase could be attributed to better training that improved healthcare worker’s knowledge and also efforts of the Traditional Leaders. These findings corroborate the findings in separate studies by Taiwo et al. (2017), and Birukila et al.(2016) in Kaduna state Nigeria who found that vaccine uptake and coverage is due to the health care worker’s knowledge and impact of mobilisation by traditional leaders [29,30].We found that 15 (75%) of the northern states recorded better coverages in 2017/2018 MVC than their respective coverages in 2015/2016 MVC. Of the five states that had a better coverage in 2015/2016 MVC, three states; Borno, Kaduna and Benue states had serious insecurity issues during the 2017/2018 campaign which resulted in reported interruption of vaccination activities during the campaign. This could be attributed to the poor performance as a similar result was reported in an assessment conducted on the risk of polio vaccination in Borno state, and the 2018 Nigeria Polio Emergency Plan by the NPHCDA emphasised the challenges of vaccination in security-compromised areas [31]. Generally, the 2017/2018 national measles vaccination was adjudged as one of the best measles vaccination campaign in recent time due to the huge number of zero doses reached and better coverage compared to the previous ones [20]. There were lots of innovations introduced in the planning and actual implementation of the campaign and engagement of the Northern Traditional Leaders was one of such innovations in the northern states due to the availability of an organised structure – The Northern Traditional Leaders Committee –, which the National Measles Technical Coordinating Committee latched on. Their contributions with other innovations can be seen to have contributed to the modest improvement in the outcome of the 2017/2018 measles vaccinaton campaign. Our study was limited by the fact that several activities of the NTLC and other religious leaders were not documented as there was no systematic mechanism for data collection which would have fully estimated the impact of the NTLC activities during the 2017/2018 measles vaccination campaign. Secondly, factors like adequate planning, political involvement, quality training of healthcare workers and intensified supportive supervision of vaccination process and not only the support of the NTLC could have been the reason behind the improved performance during the 2017/2018 MVC.

CONCLUSION

The impact of Traditional Leaders is evident at each level of decision making and in the patriarchal society of northern Nigeria; this provides a trusted and influential platform for directly engaging them on important issues such as the measles vaccination campaign and other primary health care services in the country. These commitments serve to act as recommendations for the future on how traditional leaders can drive change in Nigeria.

There will be a need to have the traditional institutions in the Southern part of Nigeria to develop a similar platform that will support primary health care service delivery. It is also necessary to have harmonised data tools that are adopted by all stakeholders to be used by traditional leaders for SIAs as well as routine immunisation services. These harmonised tools will give a robust interpretation of the traditional leaders’ activities in supporting data for action at the primary health care level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We wish to acknowledge the immense support of the Northern Traditional Leaders Committee for Primary Health Care, the states measles technical coordinating committee, the National Polio Emergency Operation center (EOC) especially the Incident manager – Dr Usman Adamu who always ensured that the NMTCC was included in the NTLC’s meeting agenda.We also acknowledge Dr Peter Nsubuga of Global Public Health Solutions for the support in building the teams’ capacity in writing.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

SK, AJO, and LT conceived the study idea and contributed to the study design and literature search. SK, AJO, BD, SB, JA, AEJB, and NO contributed to data collection, preparation of figures and tables, and performed the analysis. All authors contributed to interpretation and writing.

RESEARCH DATA FOR THIS ARTICLE

Some of the data sets used in this paper are publicly available via the sources referenced in the manuscript. Other data was generated as part of the activities supporting the measles elimination strategy and SIA.

FUNDING

This research was part of the documentation of the best practices from the 2017/2018 Measles vaccination campaign and did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not for profit sectors.

REFERENCES

6. Logan C. Traditional Leaders in Modern Africa: Can Democracy and The Chief Co-Exist?. 2008.

9. Walyben; Traditional Rulers and Local Government in Nigeria. 2022.

13.World Bank Help from Northern Traditional Leaders Catalyses Polio Decline in Nigeria (online). 2010.

18.National Bureau of Statistics, National Primary Health Care Development Agency 2018 Post Measles Campaign Coverage Survey Main Survey Report Abuja Nigeria.

19.National Primary Health Care Development Agency & Partners 2016 Measles Vaccination coverage survey - Final technical report Abuja Nigeria.

28.Davidson M. Global Issues in Vaccine Hesitancy Impacts of vaccine refusal on the global efforts to eradicate polio: The case of Nigeria Can Int Immun Initiat. 2012.