From ER to ICU: Early Fixation after TBI under a Neuron‑Derived sEV/miR‑21 Inflammation Axis-Case Report and Translational Synthesis

- 1. Center for General Education, Chung Yuan Christian University, Republic of China

- 2. Department of Trauma, Yi?Her Hospital, Choninn Medical Group, Republic of China

Abstract

Background: Early definitive fixation improves pulmonary outcomes and mobilization in polytrauma. In traumatic brain injury (TBI), timing remains contested due to risks of secondary brain insults. Translational data suggest that parenchymal TBI releases neuron?derived small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) enriched with miR?21?5p and triggers systemic inflammatory/neuropeptidergic responses, potentially accelerating callus formation while increasing neurogenic heterotopic ossification (NHO) risk.

Case: A 58?year?old man sustained severe TBI (Glasgow Coma Scale 6) with a Pipkin IV femoral head fracture (ISS 22). Neurocritical care lowered intracranial pressure medically; no decompressive craniotomy was performed. After physiological stabilization, the hip injury underwent open reduction and internal fixation via an anterolateral (Watson–Jones) approach. The case is framed across the emergency department–intensive care unit (ER–ICU) continuum with a physiology?gated algorithm.

Discussion: Evidence supports early definitive fixation once resuscitation targets are met. A neuron?derived sEV/miR?21–inflammation axis provides a mechanistic rationale for expedited osteogenesis after TBI, while underscoring proactive NHO surveillance/prophylaxis.

Conclusion: A physiology?gated strategy reconciles neuroprotection with early fixation after TBI; the present case illustrates feasibility without craniotomy, consistent with vesicle? and cytokine?mediated systemic effects.

Keywords

• Traumatic brain injury

• Small extracellular vesicles

• miR?21?5p

• Early fixation

• Femoral head fracture

• Heterotopic ossification

• Emergency medicine

• Critical care

INTRODUCTION

Early definitive fixation (EDF) of major fractures reduces pulmonary complications and resource use in polytrauma. Timing is debated in the presence of severe TBI. Contemporary practice favors physiology-gated EDF once hemodynamic, respiratory, and neurophysiologic goals are achieved. In parallel, neuro-orthopaedic biology suggests that TBI accelerates osteogenesis via vesicle-borne microRNAs and systemic inflammatory signals. This report integrates a severe-TBI case with a translational framework supporting EDF after resuscitation.

CASE PRESENTATION

We treated severe TBI using contemporary physiology gates: an intervention band around intracranial pressure (ICP <22?mmHg) with a pragmatic 20-25?mmHg range for high-risk maneuvers, a CPP target of 60–70?mmHg individualized by cerebrovascular autoregulation, and SpO? ≥94% with normocapnia. Where available, brain oxygen monitoring guided therapy toward PbtO? ≥15?mmHg, which reduces the burden of brain hypoxia compared with ICP-only management [11,12]. For respiratory readiness to proceed to early definitive fixation, we maintained a PaO?/FiO? ≥300, consistent with remaining outside the ARDS range defined by the Berlin criteria [5]. Metabolic resuscitation continued until lactate trended <2?mmol/ L-more stringent than classic Early Appropriate Care thresholds (lactate <4?mmol/L, pH?≥?7.25, base excess ≥?−5.5) to ensure oxygen delivery/consumption balance before surgery [4,11].

ER–ICU Resuscitation Targets and Monitoring

Vasopressors were used after adequate volume resuscitation to secure CPP. Both norepinephrine and phenylephrine increase MAP/CPP, yet their effects on microcirculation and brain tissue oxygenation (PbtO?) are heterogeneous. A systematic review highlights limited outcomes-level evidence to prefer one agent universally, reinforcing a monitoring-guided approach [13]. Accordingly, we titrated the minimal effective vasoactive dose to reach CPP goals while coupling decisions to multimodal monitoring (ICP/CPP ± PbtO?) rather than treating CPP in isolation [11,12].

Discussion-Vasopressors and Brain Oxygenation

Given early hypercoagulability after head injury, we used an imaging-plus-hemostasis dual threshold to initiate prophylaxis once serial head CTs were stable and coagulopathy acceptable. Trauma and neurocritical-care guidance support starting LMWH/UFH within 24–72?h in appropriately selected TBI patients [11,14,15]. In a 4,951-patient multicenter cohort, each day of delay was associated with an 8% increase in VTE odds, and initiating >72?h after injury carried an ≈4-fold higher VTE risk compared with earlier start, without an increase in mortality [16,17]. Operationally, these data argue against deferral beyond the early window when imaging is stable (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

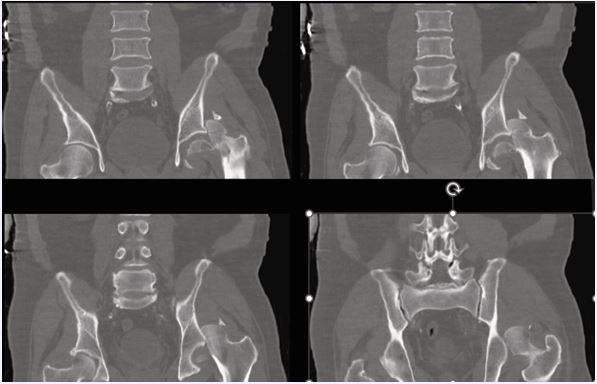

Figure 1 Pre-operative pelvic CT (coronal reconstructions) Coronal CT demonstrating a femoral head fracture with associated acetabular rim fragment consistent with Pipkin IV.

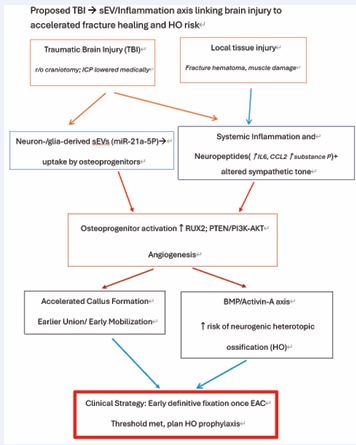

Figure 2 Proposed TBI→sEV/miR-21–inflammation axis Schematic showing neuron-/glia-derived sEV (miR-21-5p) and inflammatory/neuropeptidergic signals converging on osteoprogenitors, accelerating callus while increasing neurogenic HO risk; applicable even without craniotomy

Discussion-Timing of Pharmacologic VTE Prophylaxis

Traumatic brain injury rapidly establishes an osteo-permissive milieu via neuron/glia-derived small extracellular vesicles enriched with osteogenic microRNAs such as miR-21-5p, alongside a systemic surge in IL-6/ CCL2 and neuropeptidergic signaling (e.g., Substance?P), which together promote endochondral ossification and may accelerate callus while increasing neurogenic HO risk [6,7,9]. Because prophylactic radiotherapy is most effective within 24?h pre-op or ≤72?h post-op, and NSAIDs carry fixation-specific risks (e.g., posterior-wall nonunion), we recommend formal HO risk-stratification by postoperative days 3–5 and early scheduling of prophylaxis for high-risk hips/approaches [18,19,21] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Pre-operative hip CT (sagittal reconstructions) Sagittal reconstructions highlighting intra-articular fragments and femoral head involvement.

Discussion-Early HO Surveillance and Prophylaxis

Timing practices vary internationally: the Western Trauma Association promotes early initiation when neuroimaging is stable, the Neurocritical Care Society supports chemoprophylaxis 24–48?h after a stable scan (and resumption ~24?h after neurosurgical procedures if stable), and ACS-TQIP 2024 emphasizes a 24–72?h window with repeated reassessment [11,14,15]. We adapt to age by accepting CPP toward 60–65?mmHg in frail or vasculopathic patients (escalating only if PbtO? or autoregulation data warrant) and to injury severity by starting LMWH as soon as the first stable repeat CT allows while using immediate mechanical prophylaxis during any mandated delay. In the present case, intracranial hypertension was controlled medically without craniotomy; because the vesicle/ inflammatory responses arise from parenchymal injury per se, the mechanistic rationale for timely fixation and early HO vigilance applies directly (Figure 4).

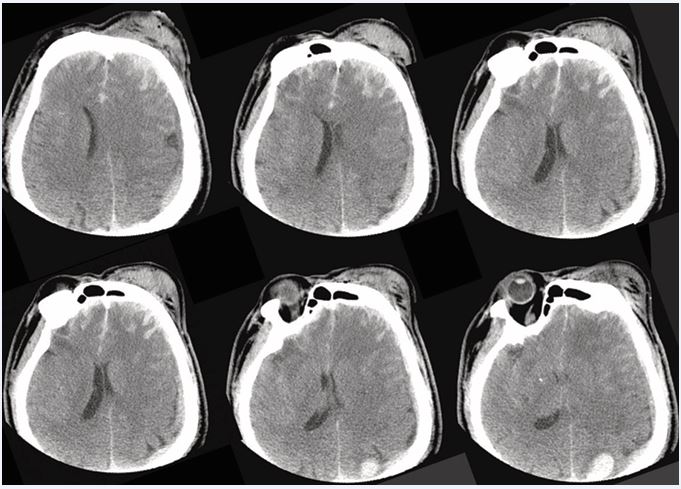

Figure 4 Admission head CT (axial slices) Representative axial images demonstrating parenchymal injury and edema in the acute phase of TBI.

Practice Variability and Individualized Thresholds

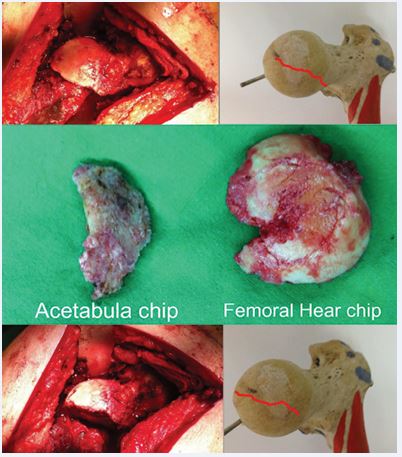

A 58-year-old man was transported after a high-energy motor-vehicle collision. On arrival, Glasgow Coma Scale was 6 (E1V1M4). Imaging showed severe TBI and a femoral head fracture with acetabular involvement (Pipkin IV); ISS 22. Airway control, neuroprotective ventilation, hemodynamic stabilization, and temperature management were instituted. Intracranial hypertension was controlled medically with hyperosmolar therapy and sedation; no craniotomy was performed. Once physiology met early-appropriate-care targets, open reduction and internal fixation was performed via an anterolateral (Watson–Jones) approach, followed by coordinated VTE prophylaxis and pulmonary hygiene, and surveillance for HO and femoral head viability (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Intra-operative views and retrieved fragments Watson–Jones exposure with removal of acetabular rim and femoral head fragments; bone model outlines the fracture line orientation.

Translational Bridge: Neuron-derived sEV/miR-21 and Inflammatory Axes

Parenchymal TBI releases neuron-/glia-derived sEVs that traffic to osteoprogenitors and deliver osteogenic miRNAs, with miR-21-5p repeatedly implicated as a pro-osteogenic cargo. TBI also elicits systemic elevations in IL-6 and CCL2 and neuropeptidergic signaling (Substance P), supporting PI3K–AKT and BMP pathways. These converging signals can enlarge and mineralize callus yet increase neurogenic HO risk. Crucially, these effects arise without the need for craniotomy and therefore apply to the present case (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Radiographs and early rehabilitation Pre-operative and post-operative anteroposterior pelvis radiographs without noticed avascular necrosis at left femoral head with early mobilization photographs at follow-up.

Timing and ER–ICU algorithm

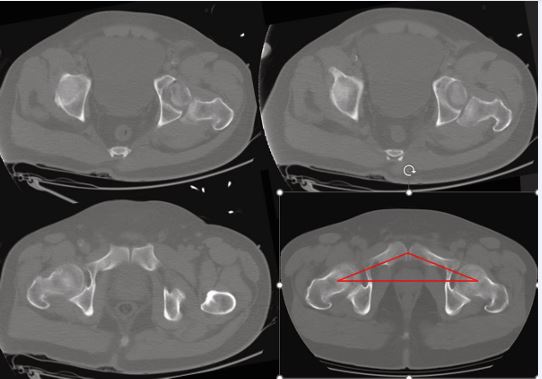

Proceed to EDF within ~24–36 h when oxygenation is adequate on lung-protective ventilation, vasopressor needs are stable or decreasing, acidosis/coagulopathy are corrected, and intracranial pressures are acceptable. Otherwise favor damage-control fixation with staged conversion. Because TBI biology may accelerate callus consolidation, timely anatomic reduction and fixation are advantageous once criteria are met; plan HO prophylaxis and neurosurgically aligned VTE prevention in parallel (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Axial pelvic CT for pre-operative planning Axial reconstructions across the hip joint; bottom-right panel includes a red overlay illustrating the acetabular roof contour/orientation used for planning.

CONCLUSIONS

EDF can be executed safely after TBI under a physiology-gated protocol. The sEV/miR-21 and inflammatory axes provide a biologic rationale for EDF while emphasizing proactive HO risk management.

REFERENCES

- Bone LB, Johnson KD, Weigelt J, Scheinberg R. Early versus delayed stabilization of femoral fractures: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989; 71: 336-340.

- Jaicks RR, Cohn SM, Moller BA. Early fracture fixation may be deleterious after head injury. J Trauma. 1997; 42: 1-5.

- Scalea TM, Scott JD, Brumback RJ, Burgess AR, Mitchell KA, Kufera JA, et al. Early fracture fixation may be ‘just fine’ after head injury: no difference in CNS outcomes. J Trauma. 1999; 46: 839-846.

- Vallier HA, Moore TA, Como JJ, Wagner KG, Smith CE, Wang XF, et al. Complications are reduced with an early appropriate care protocol for patients with femoral and pelvic fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2015; 10: 155.

- Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012; 307: 2526-2533.

- Xia W, Xie J, Cai Z. Damaged brain accelerates bone healing by releasing small extracellular vesicles that target osteoprogenitors. Nat Commun. 2021; 12 :6043.

- Lin Z, Xiong Y, Sun Y, Zeng R, Xue H, Hu Y, et al. Circulating miRNA-21–enriched extracellular vesicles promote bone remodeling in traumatic brain injury patients. Exp Mol Med. 2023; 55: 587-596.

- Haffner-Luntzer M, Fischer V, Ignatius A. Altered early immune response after fracture and traumatic brain injury. Front Immunol. 2023; 14: 1074207.

- Wong KR, Trudel G, Marchand-Leroux C. Neurological heterotopic ossification: novel mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Bone Res. 2020; 8: 33.

- Zheng J, CENTER-TBI Investigators. Early vs late fixation of extremity fractures among adults with traumatic brain injury. JAMA Netw Open. 2024; 7: e241556.

- American College of Surgeons. Best Practices Guidelines: Traumatic Brain Injury. 2024.

- Okonkwo DO, Shutter LA, Moore C. Brain tissue oxygen monitoring and management in severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized trial (BOOST-II). Neurosurgery. 2017; 81: 509-520.

- Lloyd-Donald P, Spencer W, Cheng J, Romero L, Jithoo R, Udy A, et al. In adult patients with severe TBI, does norepinephrine-augmented CPP improve outcomes? A systematic review. Injury. 2020; 51: 2129- 2134.

- Ley EJ, Brown CVR, Moore EE, Sava JA, Peck K, Ceisla DJ, et al. Updated guidelines to reduce venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions Algorithm. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020; 89: 971-981.

- Nyquist P, Bautista C, Jichici D, Burns J, Chhangani S, DeFilippis M, et al. Prophylaxis of venous thrombosis in neurocritical care patients: a guideline from the Neurocritical Care Society. Neurocrit Care. 2016; 24: 47-60.

- Byrne JP, Mason SA, Gomez D. Association of VTE prophylaxis timing with outcomes after urgent neurosurgical intervention for TBI. JAMA Surg. 2022.

- Al-Dorzi HM, Al-Harbi SA, Tamim HM. Timing of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and outcomes in moderate-to-severe TBI. Ann Thorac Med. 2022; 17: 120-127.

- Mourad WF, Packianathan S, Shourbaji RA. Prolonged delay between trauma and prophylactic radiation increases HO risk. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012; 82: e339–e344.

- Moore KD, Goss K, Anglen JO. Indomethacin versus single-doseradiation for HO prophylaxis after acetabular fracture surgery: randomized prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998; 80: 259- 263.

- Blokhuis TJ, Frölke JP. Is radiation superior to indomethacin to prevent HO in acetabular fractures? A systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009; 467: 526-530.