Effect of Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor use on Time to HIV Viral Suppression before Delivery

- 1. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical University of South Carolina, USA

- 2. Department of Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, USA

Abstract

Background: We sought to determine if pregnant persons with HIV prescribed integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI) antiretrovirals (ARVs) achieve viral suppression faster than persons taking non-INSTI regimens and to

Methods: This is a retrospective cohort study of pregnant persons with HIV who delivered a live infant during the study period (1/1/2009 to 12/31/2020). Persons’ ART was classified as including INSTI or non-INSTI. We compared the proportion of persons with viral suppression at delivery by group and individual INSTI ARVs using χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests. A log-rank test was used to compare time to viral suppression on ARVs.

Results: During the study period, 168 persons delivered a live infant. Most persons were diagnosed with HIV before pregnancy and had taken ARVs before conception (76%), but less than half had an undetectable viral load at the first antenatal visit (45%). During pregnancy, 46% of persons were prescribed INSTI and 54% non-INSTI ARVs. Most persons had an undetectable HIV RNA viral load at delivery (75% INSTI and 72% non-INSTI, p=0.7). The time to viral suppression was similar between groups (LRT p=0.43). Viral suppression at delivery was similar between INSTI ARVs: raltegravir (53%), elvitegravir (88%), dolutegravir (73%), and bictegravir (88%) (p=0.13).

Conclusion: Despite recommendations to prescribe INSTI in pregnancy for rapid viral suppression, we did not find a significant difference in time to viral suppression when pregnant persons were taking non-INSTI ARVs. We did not find that one INSTI ARV was superior for viral suppression.

Keywords

Human immunodeficiency virus, integrase strand transfer inhibitors, Pregnancy, Viral suppression, Perinatal

ABBREVIATIONS

INSTI: integrase strand transfer inhibitors; ARVs: antiretrovirals; ART: antiretroviral therapy; RAL: raltegravir; EVG: elvitegravir; DTG: dolutegravir; BIC: bictegravir; CAB: cabotegravir; NRTI: nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; STR: single tablet regimen; ABC: abacavir; 3TC: lamivudine; COBI: cobicistat; EMR: electronic medical record; ANV: antenatal visit; GA: gestational age; IQR: interquartile range.

Citation

Nissim OA, Spitznagel MC, Kirk SE, Tarleton JL, Lazenby GB, (2022) Effect of Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor use on Time to HIV Viral Suppression before Delivery. Clin Res HIV/AIDS 8(1): 1052.

INTRODUCTION

Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTI) are a class of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) for the treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Compared to other antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), INSTI use results in a more rapid reduction in HIV RNA viral load (copies/mL) [1], and is associated with a higher barrier to development of drug resistance [2,3]. HIV RNA viral load is a significant predictor of the risk for perinatal HIV transmission to HIV-exposed infants during pregnancy. Maintaining viral load suppression on ART throughout pregnancy is crucial for maternal health and decreases the risk of perinatal transmission to 1-2% [4]. As of 2015, the Department of Health and Human Services HIV Perinatal Treatment guidelines have recommended INSTI use during pregnancy [5].

The first INSTI, raltegravir (RAL) was approved by the FDA in 2007. Since that time, new INSTI ARVs have been approved for HIV treatment: elvitegravir (EVG 2012), dolutegravir (DTG 2013), bictegravir (BIC 2018), and cabotegravir (CAB 2021). Due to a higher barrier of resistance compared to RAL and EVG, DTG and BIC are preferred ARVs for the treatments of adults with newly diagnosed HIV [2]. With the exception of RAL, INSTI are available in combination pills that can be administered once daily to improve treatment adherence [6]. Current guidelines recommend either RAL or DTG in combination with 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) as preferred INSTI-based regimens for pregnant persons newly diagnosed with HIV [5]. However, there is only one single-tablet-regimen (STR) option with this combination (DTG/ABC/3TC), but genetic testing is necessary to rule out anaphylaxis prior to use of abacavir. As STR have been shown to improve treatment adherence and decrease hospitalization rates [7], establishing safety of new STR including INSTI ARVs is paramount in order to recommend their use during pregnancy [8].

Despite being highly effective and preferred ART for HIV treatment, data regarding safe use of INSTI in pregnancy is limited [9]. Zash et al demonstrated that viral suppression during pregnancy was similar when comparing DTG-based and efavirenz-based (EFV) regimens [10]. From this same Botswanan cohort, the authors reported that DTG use in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of neural tube defects [11]. Following this publication, many reproductive age persons were not prescribed DTG for treatment of their HIV. Subsequent data from the for-mentioned Tsepamo study reported a smaller than previously estimated risk of neural tube defect associated with preconception DTG use (0.19%) in comparison to a non- DTG regimen (0.11%) [12]. DHHS recommendations have been updated to include DTG as a preferred regimen during conception and all trimesters [5]. A more recent trial comparing two DTGbased regimens and EFV-based ART reported pregnant persons prescribed DTG-based regimens reached viral suppression (< 50 copies/mL) earlier and were more likely to be virologically suppressed at time of delivery [1].

EVG is not a preferred ARV for use in pregnancy. Pharmokinetic studies have indicated that EVG/COBI metabolism during pregnancy may result in inadequate drug levels in the 3rd trimester resulting in a theoretical increase in maternal HIV viral load and subsequent risk of perinatal HIV transmission [13]. For persons who desire to continue EVG/COBI during pregnancy, frequent viral load monitoring is recommended [5]. Two prior multi-center studies of RAL and EVG use in pregnancy have demonstrated successful maternal virologic suppression (HIV RNA viral load < 40 copies/mL) [14, 15]. Further clinical

studies are needed to determine if EVG/COBI effectively results in virologic suppression in late pregnancy. Safety data are too limited to recommend initiation or continuation of bictegravir during pregnancy [16].

When evaluating a cohort of persons with HIV-1 in our academic medical center, we identified a substantial number were prescribed non-INSTI regimens or non-preferred INSTI ART during pregnancy. Our objective was to evaluate the difference in time to viral suppression during pregnancy between persons prescribed INSTI and non-INSTI ART. We also sought to determine if there are differences in viral suppression between INSTI regimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

This is a retrospective cohort study of pregnant persons with HIV who delivered a live infant at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) during the study period (January 1, 2009 to December 31, 2020) (IRB Pro00108838). Potential subjects were identified from a clinical database of all pregnant persons with HIV receiving antenatal care at our urban, academic medical center antenatal clinic. Persons who did not receive antenatal care or deliver at our center were excluded.

The electronic medical records (EMR) of each eligible subject were reviewed by a single investigator (M.S.) to abstract study variables. Variables abstracted from the EMR were grouped as maternal descriptive, antenatal, and HIV-specific care. Descriptive variables were: maternal age in years at time of delivery; selfreported race recorded as white, black, or other; and self-reported ethnicity recorded as Hispanic or non-Hispanic. Antenatal variables were: date of first antenatal visit (ANV), gestational age (GA) at first ANV, number of ANVs before delivery, date of delivery, GA at delivery, and type of delivery (vaginal or cesarean). HIVspecific variables were: year of HIV diagnosis, ARVs prescribed before the first ANV (if applicable), ARVs prescribed during antenatal care and delivery, dates(s) ARVs were prescribed, GA when ART was prescribed, HIV RNA viral load(s) (copies/mL), date(s) of viral load collection(s), CD4 cell count (cells/mm3), and dates of CD4 cell count collection(s).

In our hospital system, RNA quantification is calculated using Abbott RealTime HIV-1 assay m2000© (Abbott park, IL). HIV-1 RNA viral load is reported in our EMR as “undetectable” which is below the level of detection, < 40 copies/mL (which detects low levels of virus above “undetectable”), or as an absolute number > 40 copies/mL. “Undetectable” viral loads were assigned a value of zero in the data collection tool. Some data abstracted from the EMR were used to calculate additional study variables. Using the dates of the initial antenatal visit and delivery, we calculated the number of days persons were in antenatal care. For persons who entered care with a detectable viral load (≥ 40 copies/mL), we calculated the time to viral suppression (< 40 copies/mL) by subtracting the date of entry into care from the first date at which viral suppression was noted. Once viral suppression was achieved, we also noted any increase in viral load (≥ 40 copies/ mL) described as a “viral blip” after previous suppression and the date which this occurred.

Statistical analysis

Persons were grouped by ART regimen: INSTI or non-INSTI. Persons taking INSTI ART were further categorized by drug: RAL, EVG, DTG, and BIC. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were used for bivariate comparisons between groups such as the percentage of persons with viral suppression at delivery. A survival analysis (log-rank test) was used to demonstrate differences in time (days) to accomplish viral suppression between study groups. A Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine normality of continuous variables. A Freidman test (a non-parametric test to compare repeated measures which are not normally distributed) was used to compare difference in repeated viral load values between study groups. Wilcoxon Rank Sums and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine the differences between the medians of

continuous variables, i.e. maternal age at delivery and gestational age at delivery. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS® 9.4 (Cary, NC). Missing data were indicated by the corresponding denominator.

Sample size

Our study period (accrual time) was 8 years (2,920 days). The follow up period of antenatal care was approximately 30 weeks (210 days). We assumed that persons prescribed non-INSTI ART would achieve viral suppression in approximately 60 days (median), and persons prescribed INSTIs would achieve viral suppression in 30 days. In order to find this presumed difference in survival times, we would need 33 subjects in each group in order to reject the null hypothesis that the groups’ survival curves are equal with a probability (power) of 0.8. The Type I error probability associated with this test of this null hypothesis is 0.05.

RESULTS

During the study period, 190 persons with HIV were registered in our clinical database. Of these, 168 persons had live births at our hospital and 167 persons were prescribed ART during pregnancy, 77 INSTI and 90 non-INSTI. Persons on INSTI (77) ART were subcategorized by drug with detailed ART data available for 76 persons: RAL (13), EVG (33), DTG (22), and BIC (8). The median maternal age at delivery was 26 years [interquartile range (IQR) 23-30]. Median maternal age was 26 years for both persons prescribed INSTI (IQR 23-29) and non- INSTI (IQR 23-31). Similar percentages of persons from both groups self-reported their race as Black (INSTI 77% and non- INSTI 75%) and ethnicity as non-Hispanic (INSTI 91% and non-INSTI 93%).

| INSTI N, 77 (%) |

Non-INSTI N, 90 (%) |

|

| GA at initial antenatal visit* | 12 (IQR 7-17) | 13 (IQR 10-20) |

| Initial HIV RNA viral load (copies/mL) | 457 (IQR 0- 8,438) | 114 (IQR 0- 5,274) |

| Initial CD4 cell count (mm3) | 427 (IQR 289-539) | 503 (IQR 313-693) |

| Change in ART regimen during pregnancy | 15/67 (22 %) | 15/70 (21 %) |

| GA when ART regimen change occurred | 19 (IQR 14-24) | 17 (IQR 11-26) |

| HIV RNA viral load blip following suppression | 13/74 (18 %) | 9/85 (11 %) |

| Days enrolled in antenatal care before delivery | 162 (IQR 98-194) | 162 (IQR 107-188) |

| Viral suppression before delivery | 58 (75 %) | 65 (72 %) |

| CD4 cell count (mm3) before delivery | 435 (IQR 317-562) | 509 (IQR 341-677) |

| GA at delivery | 38 (IQR 37-39) | 38 (IQR 37-39) |

| Cesarean delivery | 38 (49 %) | 36 (40 %) |

Seventy-seven percent of persons were diagnosed with HIV and previously prescribed ART before pregnancy (128/167); the percentage of persons in each study group with a previous diagnosis and ART exposure was also 77% (p=0.9). Fewer than half of persons (n= 75, 45%) had an initial undetectable initial viral load (< 40 copies/mL). The percentage of persons with an initial undetectable viral load was similar in the INSTI and non-INSTI ART groups (43% vs 46%, p=0.4). Twenty percent of persons changed their ART during pregnancy (n=30); the percentage of persons with a change in ART was similar between

INSTI and non-INSTI ART groups (22% vs 21%, p=0.9). The median gestational ages at which ART changes occurred were similar between groups (INSTI 19 weeks and non-INSTI 17 weeks, p=0.7) (Table 1).

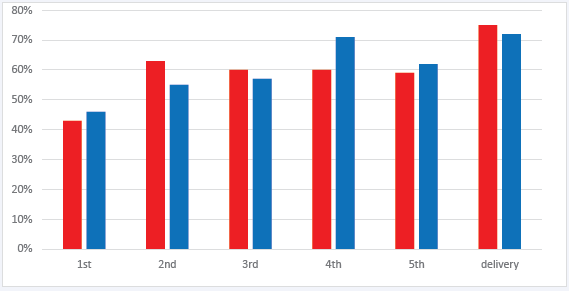

Figure 1: Percentage of pregnant persons with an undetectable HIV RNA viral load during antenatal care in order of collection and according to antiviral regimen.

Legend: Red bar= INSTI ART, blue bar= non-INSTI ART. Y-axis, percentage of persons with undetectable viral load. X-axis, viral load evaluation in order of collection during pregnancy.

The frequency of viral load collection during antenatal care ranged from 1 to 9 measurements before delivery; less than 20% of persons in either group had more than 6 viral load measurements before delivery. The percentage of persons with viral suppression at each subsequent evaluation of viral load were similar between INSTI and non-INSTI groups (Figure 1). χ2 analyses comparing the percentage of persons with viral suppression in the INSTI and non-INSTI groups at each time point of viral load evaluation during pregnancy did not detect a significant difference between groups at any point (1st VL p= 0.7, 2nd VL p=0.3, 3rd VL p=0.7, 4th VL p=0.3, 5th VL p=0.8, and VL before delivery p=0.7).

| Raltegravir N, 13 (%) |

Elvitegravir N, 33 (%) |

Dolutegravir N, 22 (%) |

Bictegravir N, 8 (%) |

|

| Initial HIV RNA viral load (copies/mL) | 87 (IQR 0- 21,278) |

111 (IQR 0- 7,328) |

2762 (IQR 0- 13, 485) |

0 (IQR 0- 9,148) |

| Viral blip following suppression | 2/12 (17 %) | 6 (18 %) | 4/21 (19 %) | 1/7 (14 %) |

| Viral suppression at delivery | 7 (54 %) | 28 (85 %) | 16 (73 %) | 7 (88 %) |

Abbreviations:

INSTI: integrase strand transfer inhibitor;

GA: Gestational age was expressed in weeks; ART: antiretroviral therapy;

IQR: interquartile range. A viral load blip was defined as an observed increase in HIV RNA viral load ≥ 40 copies/mL following viral suppression. Continuous variables are reported as medians with corresponding IQR and compared using Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests. Bivariate variables are reported as the absolute number observed with corresponding percentage and compared using χ2 analyses. * denotes p < 0.05.

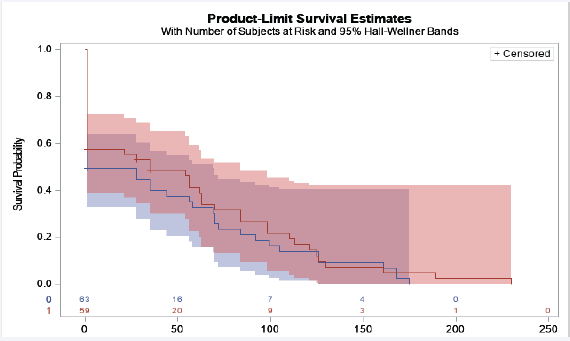

Most persons with HIV had undetectable viral load at delivery (123/167, 73%); 75% INSTI and 72% non-INSTI (p= 0.7). The percentage of persons with viral suppression at delivery was not significantly different between INSTI ARVs: RAL (53%), EVG (88%), DTG (73%), and BIC (88%) (p=0.13) (Table 2). The median time (days) to viral suppression was similar between groups (INSTI 77 days and non-INSTI 71 days, p=0.8). The survival analysis did not show a significant difference between time to viral suppression (LRT p=0.4) (Figure 2). The Friedman test to compare repeated measures of viral load over time did not demonstrate a significant difference in the median viral load values between groups (p=0.4). A similar percentage of persons in each group experienced a blip in viral load following an undetectable HIV RNA in pregnancy (INSTI 18% and non-INSTI 11%, p=0.2). The percentage of persons experiencing a blip was similar between INSTI drugs (RAL 17%, EVG 18%, DTG 19%, and BIC 14%, p=0.99) (Table 2).

Figure 2: Time in days before viral suppression was achieved after ART initiation and before delivery

Legend: Red line= INSTI ART, blue line= non-INSTI ART. Y-axis, probability of viral suppression. X-axis, time in days to achieve viral suppression. Participants were censored once viral load < 40 copies/mL. The time in days to viral suppression was similar between INSTI and non-INSTI groups, Log-rank test p= 0.43.

Less than half (41%) of persons had a cesarean delivery; and the percentages of persons undergoing cesarean delivery were similar between groups (p=0.2). Of note, one HIV-exposed infant was diagnosed with perinatal HIV infection. The mother was prescribed RAL, but she had a detectable viral load at the time of delivery. The most likely explanation for this was ART non-adherence resulting in inadequate viral suppression before delivery.

DISCUSSION

While INSTI use has been associated with rapid HIV viral suppression, we did not observe a significant difference in time to viral suppression in pregnant persons taking INSTI and non-INSTI ART. The percentage of pregnant persons prescribed ART experiencing a blip in viral load following an undetectable HIV RNA during pregnancy was similar between groups. Notably, a larger sample size in each group may have determined a significant difference in viral load blips potentially favoring improved sustained viral suppression in the non-INSTI group. Our findings suggest that providers may prescribe either INSTI or non-INSTI regimens without concern for differential rates of viral suppression before delivery.

Maintaining viral suppression is key to prevention of perinatal HIV transmission [4]. When prescribing ARVs in pregnancy, providers should discuss potential drug interactions in order to reduce the risk of viral rebound. For example, when DTG is taken with metal cation-containing medications (i.e. calcium or iron) on an empty stomach, serum plasma concentration of DTG is lower compared to when taken with food [17]. Both calcium and iron are found in prenatal vitamins, and patients should be counseled to take DTG with food if taking ART and prenatal vitamins at the same time. When prescribing ART to pregnant persons, providers should also consider drug safety, tolerability, and efficacy. Additional factors that influence ART selection include pill size, ability to crush, and drug-drug interactions. We found that approximately twenty percent of persons in both study groups had an ART regimen change during pregnancy. Change in ART could potentially increase the risk of viral blips or rebound during pregnancy. Change in ART during pregnancy may also be in reaction to failure to achieve viral suppression or in reaction to viral rebound. We are not able to describe the clinical reasoning for ART change during pregnancy, but we did observe that most persons achieved viral suppression before delivery regardless of ART regimen.

Raltegravir and dolutegravir are preferred ARVs for pregnant persons [5]. RAL requires twice daily dosing which may impact patient drug adherence. When comparing individual INSTIs, we did not observe a significant difference in viral suppression at delivery or viral blips following undetectable viral load. Our sample size was adequate for the primary outcome but was inadequate to compare viral suppression between individual INSTI ARVs. A significant percentage of persons in the INSTI treatment group were prescribed EVG/COBI (45%). Previous pharmokinetic studies suggest that EVG/COBI metabolism during pregnancy may result in inadequate drug levels in the 3rd trimester [3]. Pregnant persons in our cohort who were prescribed EVG/ COBI had excellent viral suppression before delivery (85%) compared to other INSTI regimens with no evidence of an increased risk of viral load blips. For select patients, increased adherence associated with STR use may outweigh the theoretical risk of decreased levels of EVG/COBI in later trimesters. Compared to other INSTI ARVs, a higher percentage of persons prescribed BIC had an undetectable viral load at delivery (88%). Our sample size is too small to make a strong recommendation

for BIC use during pregnancy, but our observation of adequate viral suppression compared to DTG is promising. CAB is a newly FDA approved INSTI available in combination with rilpivirine as a Iong-acting injectable or an oral tablet [18]. Injectable ART may be appropriate for well-controlled adults with HIV [19], but no persons in this study were using CAB and its safety and efficacy in pregnancy is unknown [16]. Future studies of INSTI use during pregnancy for prevention of perinatal HIV infection should consider inclusion of BIC and CAB regimens.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings should reassure providers that most pregnant persons with HIV prescribed ART can achieve viral suppression before delivery. Perinatal HIV transmission was rare in our cohort (0.6%), and the single case observed most likely occurred due to HIV viremia in the setting of inadequate ART treatment adherence. We did not find evidence to suggest INSTI use during pregnancy results in faster viral suppression than non-INSTI ART. Although our sample size is small and despite theoretical concerns from pharmokinetic studies, we observed that similar percentages of persons achieved viral suppression when prescribed EVG and

BIC when compared to RAL and DTG. Future studies should be inclusive of all INSTI regimens use among pregnant persons in order to inform provider ART prescribing practices.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

This manuscript is the work of the listed authors. This observational study was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina IRB Pro #00102343. Individual consent was not required due to the use of de-identified respective data. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests to report.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the pregnant individuals living with HIV who have entrusted us with their care.