Hyperhomocysteinemia for Alzheimer

- 1. Department of Internal Medicine and Geriatry, Second University of Naples, Italy

Abstract

Background: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common display ofneurodegeneration. It is a multifactorial disease both at early- and late-onset. A number of studies have found that H-Hcycan be significantly correlated with increased risk of AD in the late onset form only.

Methods and Results: Several evidences shown that H-Hcy may promote AD by more than one mechanism including impair lipoprotein E genotype, involved in lipid transport and neuronal repair and synaptogenesis. But, endothelial dysfunction; neurotoxicity; apoptosis; Ca++dysregulation; neuronal DNA damage and homocysteic acid (N-methyl-D-aspartate agonist) production are also responsible of AD. Some of these have a causal connection with AD. Others act a simple marker of different conditions, such as DNA hypometilation consequent to H-Hcy. Both these mechanisms can induce AD, acting such as risk factor or marker at the same time

Conclusions: Conclusively, H-Hcy can act such as risk factor, marker, or both for AD pathogenesis by unknown mechanisms.

Keywords

• Homocysteine

• Alzheimer’s disease

• Risk factor

• Marker

CITATION

Cacciapuoti F (2016) Hyperhomocysteinemia for Alzheimer’s Disease: Risk Factor, Biomarker or Both? JSM Alzheimer’s Dis Related Dementia 3(1): 1021.

ABBREVIATIONS

AD: Alzheimer’s Disease; H-Hcy: Hyper-homocysteinemia; Hcy: Homocysrteine; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; HDL: High Density Lipoproteins; m ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; SAH: S-AdenosylHomocysteine

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the world’s most common neurodegerative disorder that continuously rises with increased lifespan. Globally, more than 26 million people have been diagnosed with AD and are projected to exceed 100 million by year 2050. Two clinical forms of AD are described: an early onset AD (rare) occurring between the ages 30-60 years that is gene-dependent. A late-onset AD (more frequent) evident over 65 to 80 years of age. A number of factors have been proposed that might account the beginning of late-onset AD. Among these: vascular derangements, advanced age, gender, renal dysfunction, behavioral problems, baseline cognitive status, lifestyle, etc. there are. Increased concentrations of homocysteine (H-Hcy) levelshave also been frequently linked with AD pathogenesis but, the relationship between AD and Hcy appears to be complicated by the aging [1-3].

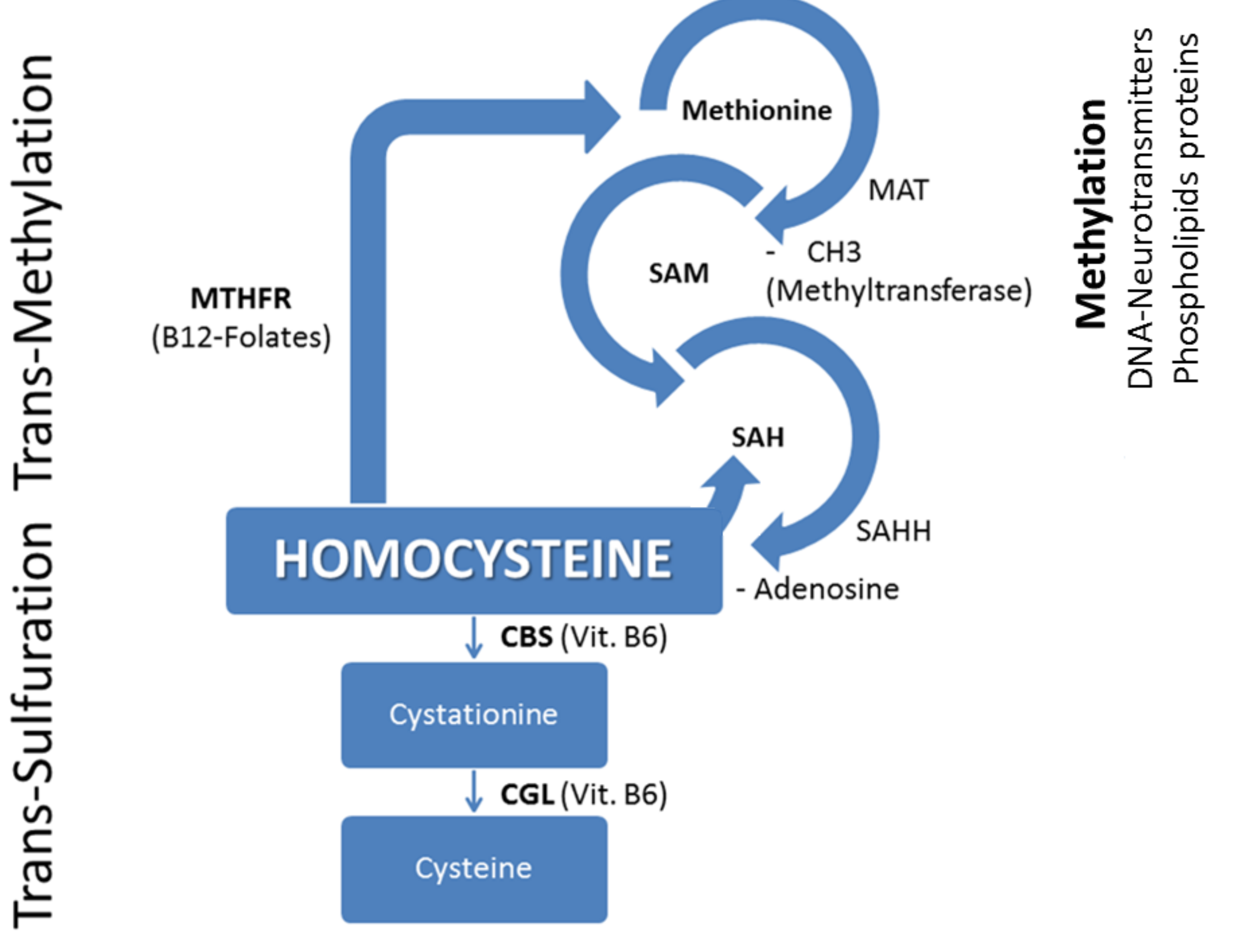

Hcy is a sulfur-containing produced from dietary methionine. When methionine levels are low, Hcy is remethylated into methionine: a process that requires vitamin B12 and folic acid as cofactors. When methionine levels are high, Hcy condensates to serine to form cystathionine, and subsequently, cysteine (through the trans-sulfuration pathway). Normally, about 50% of Hcy is remethylated, the remained Hcy is trans-sulfurated through a biochemical process requiring vitamin B6 as cofactor. This pathway yields cysteine, used to make glutathione, a powerful antioxidant that protects cellular components against oxidative damage (Figure 1).

In this report, we discuss if H-Hcy has been associated with an increased risk of developing AD or is a simple marker reflecting an underlying process responsible for both H-Hcy and the AD development.A disease risk factors can be defined as measurable biological characteristics of an individual that precede a welldefined outcome and are directly in the biological causal pathology. In contrast, biomarkers are biological indicators for processes involved in developing a disease.

Concerning this topic there is some contradictory evidence, and it remains controversial whether H-Hcy is an AD risk factor or merely biomarker. Some cohort studies suggested a direct relationship between elevated Hcy concentrations and risk for AD [1,4,5]. But, other authors did not find a cause-effect relationship between H-Hcy and AD [6]. A direct connection between H-Hcy and AD pathogenesis has been reported in the Rotterdam Scan Study [7], in the Banbury B12 Study [8] and in the Northen Manhattan Study [9] but, the Washington Heigts- In wood Columbia Ageing Project (WHICAP) reported no direct relation[6]

Figure 1 Remethylation and Trans-sulfuration of homocystein Abbreviations: MTHFR: Methylen-Tetra-Hydro-Folate-Reductase; MAT: Methyonine-Adenosyl-Transferase; SAM: S-Adenosyl-Methyonine; SAH: S-Adenosyl-Homocysteine; SAHH: SAH-Hydrolase; CBS: Cystationine-Beta-Synthase; CGL: Cystationine-Gamma-Lyase

An increased Hcy concentration can act as risk factor for AD through several mechanisms: Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype is one of the major lipid acceptors, able to remove cholesterol from cells and generate HDL particles involved in neuronal repair and synaptogenesis after injury [10].In normal conditions, APOE4 isoform exhibits higher levels of Aβ peptide, senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. So, APOE4 isoform seems to be a major risk factor for AD. On the contrary, APOE3 isoform has a protective effect. H-Hcy impairs APOE3 function, reducing APOE3-mediated HDL generation, whereas it does not affect APOE4 function. Therefore, an increased Hcy concentration seems to favour AD pathogenesis. An experimental study performed in knock-out mice confirmed that Hcy interferes with APOE3, impairing its ability to generate HDL [11]. Recently Elias and al. confirmed that cognitive decline and impaired cerebral performance directly depend on increased Hcy serum levels [12]. A positive relationship among H-Hcy, APOE and cognitive decline in older adults was also hypothesized by Bruce et al., [13]. Another study found that H-Hcy impairs the integrity of blood-brain barrier (BBB), leading to cell damage and cognitive decline until AD [14]. It is known that Hcy is excitotoxic to cortical neurons in cell culture, suggesting a causal role for the amino acid in the cholinergic deficit, typical of AD [15]. In addition, some derivative products of Hcy such as homocysteic acid, analog to glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), can act as agonist on the NMDA receptor. That induces an excitatory neurons’ damage, including cognitive impairment and AD [16,17]. In confirmation of the excitotoxic theory, a protective effect of methylcobalamin, a vitamin B12 analog, against glutamate cytotoxicity was also described [18].To further testify the neuro-degenerative effects typical of AD induced by H-Hcy, Kim et al., and Rajagopolan et al., demonstrated that elevated Hcy levels can cause hippocampal or cortical atrophy and white matter changes [19,20]. Some studies also provide evidence that H-Hcy directly could affect beta-amyloidand tau metabolism [21]. Finally, injection of Hcy into rat brain increases Aβ levels and tau phosphorylation [22,23]. Other mechanisms have been proposed to explain the connection between H-Hcy and AD, such as impaired DNA repair mechanism leading to apoptosis and other types of damages [24,25]. Schilling and Eder found that Hcy and other thiols are able to produce a variety of ROS strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease, through the Aβ stimulation by unknown mechanism [26]. Further, Tchantochou et al., demonstrated that Hcy acts by reducing the activity of some antioxidants, as gluthatione, probably by increasing gluthatione-S-transferase activity [27]. Hcy can also augment the toxicity of Aβ by exacerbating their pro-oxidant activity [28]. But, H-Hcy can also act as marker for the disease. Particularly, the prevalence of S-Adenosyl-Homocysteine(SAH) in the Methionine cycle, causes the hypomethylation of some substrates because it acts as inhibitor of methyltransferases [29]. In detail, DNA hypomethylation arrests the cells’ cycle at G1/S transition via Cyclin gene, inhibiting endothelial cells growth. This process, in turn, can be responsible for endothelial dysfunction and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, subsequently evolving to early atherosclerosis [29]. So, macroand micro-angiopathy, endothelial dysfunction, impaired nitric oxide activity and increased oxidative stress can be cause of vascular dementia and AD [30].

According to these observations, a question there is: does H-Hcy itself damage blood vessels and neurons, or it is a marker for deficiency or depletion of other interconnected compounds (SAH), or both? [31,32]. The answer to this question rises from therapeutic interventions performed with vitamins of B group. Hyperhomocysteinemic patients treated with these nutraceuticals differently reply. On the basis of their behaviour we report that, when H-Hcy acts such as a direct cause(risk factor) of AD, folates and B vitamins supplementation decreases both Hcy levels and the risk of AD [33,34]. On the contrary, if DNA hypomethylation prevails so that it is only an indicator (marker) of increased AD risk, despite folic acid and B6-12 vitamins supplementation reduces the elevated Hcy plasma levels; it does not significantly influence AD [35-37]. H-Hcy may also act as a risk factor and a marker for AD at the same time. In these cases, folates and vitamin B12 supplementation also lowers Hcy levels and prevents or delays cognitive impairment and AD [38].

CONCLUSIVE REMARKS

Some conditions dependent of H-Hcy, as DNA hypomethylation, seem to be a powerful marker than a causal factor of cognitive decline and AD. In that case, folate and vitamin B6-12 supplementation appears to be useless because it not reduce the incidence of these diseases, although lowers H-Hcy levels. But, increased Hcy levels can act as a direct cause (risk factor) of cognitive impairment and AD. When that happens, vitamin B6-12 and folic acid supplementation acts both reducing H-Hcy concentration and AD risk. Finally H-Hcy inducing AD, can behave oneself both as risk factor and marker simultaneously. In this occurrence, folate and vitamin B6-12 supplementation also reduce both Hcy serum concentration and AD risk. The different reply to B vitamins treatment we allow to hypothesize that H-Hcy may act as risk factor, marker, or both by unknown mechanisms. These conclusions are only partially in agreement with Zhuo et al., affirming that H-Hcy can be risk factor, marker or neither for AD [39]. Nevertheless, other studies with a larger sample size need to confirm or refute the conclusions reported.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no potential conflict of interest with respect to the review and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Seshadri S, Beiser A, Selhub J, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, D'Agostino RB, et al. Plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346: 476-483.

- Farkas M, Keskitalo S, Smith DE, Bain N, Semmler A, Ineichen B, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia in Alzheimer's disease: the hen and the egg? J Alzheimers Dis. 2013; 33: 1097-1104.

- Van Dam F, Van Gool WA. Hyperhomocysteinemia and Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009; 48: 425-430.

- Ueland PM, Refsum H, Beresford SA, Vollset SE. The controversy over homocysteine and cardiovascular risk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000; 72: 324-332.

- Ravaglia G, Forti P, Maioli F, Martelli M, Servadei L, Brunetti N, et al. Homocysteine and folate as risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 82: 636-643.

- Luchsinger JA, Tang MX, Shea S, Miller J, Green R, Mayeux R. Plasma homocysteine levels and risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004; 62: 1972-1976.

- Prins ND, Den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Jolles J, Clarke R, et al. Rotterdam Scan Study. Homocysteine and cognitive function in the elderly: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Neurology. 2002; 59: 1375-1380.

- Hin H, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Atoyebi W, Emmens K, Birks J, et al. Clinical relevance of low serum vitamin B12 concentrations in older people: the Banbury B12 study. Age Ageing. 2006; 35: 416-422.

- Wright CB, Lee HS, Paik MC, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Sacco RL. Total homocysteine and cognition in a tri-ethnic cohort: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology. 2004; 63: 254-260.

- Poirier J, Davignon J, Bouthillier D, Kogan S, Bertrand P, Gauthier S. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1993; 342: 697-699.

- Minagawa H, Watanabe A, Akatsu H, Adachi K, Ohtsuka C, Terayama Y, et al. Homocysteine, another risk factor for Alzheimer disease, impairs apolipoprotein E3 function. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285: 38382-38388.

- Elias MF, Robbins MA, Budge MM, Elias PK, Dore GA, Brennan SL, et al. Homocysteine and cognitive performance: modification by the ApoE genotype. Neurosci Lett. 2008; 430: 64-69.

- Bunce D, Kivipelto M, Wahlin A. Apolipoprotein E, B vitamins, and cognitive function in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005; 60: P41-48.

- Ujiie M, Dickstein DL, Carlow DA, Jefferies WA. Blood-brain barrier permeability precedes senile plaque formation in an Alzheimer disease model. Microcirculation. 2003; 10: 463-470.

- Ho PI, Ortiz D, Rogers E, Shea TB. Multiple aspects of homocysteine neurotoxicity: glutamate excitotoxicity, kinase hyperactivation and DNA damage. J Neurosci Res. 2002; 70: 694-702.

- Boldyrev AA, Johnson P. Homocysteine and its derivatives as possible modulators of neuronal and non-neuronal cell glutamate receptors in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007; 11: 219-228.

- McCaddon A, Kelly CL. Alzheimer's disease: a 'cobalaminergic' hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 1992; 37: 161-165.

- Akaike A, Tamura Y, Sato Y, Yokota T. Protective effects of a vitamin B12 analog, methylcobalamin, against glutamate cytotoxicity in cultured cortical neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993; 241: 1-6.

- Kim SR, Choi SH, Ha CK, Park SG, Pyun HW, Yoon DH. Plasma Total Homocysteine Levels are not Associated with Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy, but with White Matter Changes in Alzheimer's Disease. J Clin Neurol. 2009; 5: 85-90.

- Rajagopolan P, Hua X, Toga AW, Jack CR, Weiner MW, Thompson PM. The Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Neuro Report 2011; 22: 391-395.

- Luo Y, Zhou X, Yang X, Wang J. Homocysteine induces tau hyperphosphorylation in rats. Neuroreport. 2007; 18: 2005-2008.

- Zhang CE, Wei W, Liu YH, Peng JH, Tian Q, Liu GP, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia increases beta-amyloid by enhancing expression of gamma-secretase and phosphorylation of amyloid precursor protein in rat brain. Am J Pathol. 2009; 174: 1481-1491.

- Zhuo JM, Praticò D. Acceleration of brain amyloidosis in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model by a folate, vitamin B6 and B12-deficient diet. Exp Gerontol. 2010; 45: 195-201.

- Kruman II, Culmsee C, Chan SL, Kruman Y, Guo Z, Penix L, et al. Homocysteine elicits a DNA damage response in neurons that promotes apoptosis and hypersensitivity to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000; 20: 6920-6926.

- Kruman II, Kumaravel TS, Lohani A, Pedersen WA, Cutler RG, Kruman Y, et al. Folic acid deficiency and homocysteine impair DNA repair in hippocampal neurons and sensitize them to amyloid toxicity in experimental models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2002; 22: 1752-1762.

- Schilling T, Eder C. Amyloid-β-induced reactive oxygen species production and priming are differentially regulated by ion channels in microglia. J Cell Physiol. 2011; 226: 3295-3302.

- Tchantchou F, Graves M, Falcone D, Shea TB. S-adenosylmethionine mediates glutathione efficacy by increasing gluthatione S-transferase activity: implications for S-adenosyl methionine as a neuroprotective dietary supplement. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008; 14: 323-328.

- Ho PI, Collins SC, Dhitavat S, Ortiz D, Ashline D, Rogers E, et al. Homocysteine potentiates beta-amyloid neurotoxicity: role of oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2001; 78: 249-253.

- Jamaluddin MD, Chen I, Yang F, Jiang X, Jan M, Liu X, et al. Homocysteine inhibits endothelial cell growth via DNA hypomethylation of the cyclin A gene. Blood. 2007; 110: 3648-3655.

- Welch GN, Loscalzo J. Homocysteine and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338: 1042-1050.

- Seshadri S. Elevated plasma homocysteine levels: risk factor or risk marker for the development of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzh Dis. 2006; 9: 393-398.

- Miller AL. The methionine-homocysteine cycle and its effects on cognitive diseases. Altern Med Rev. 2003; 8: 7-19.

- Holford P. The prevention of memory loss and progression to Alzheimer’s disease with B vitamins, Antioxidants and essential fatty acids: a review of evidence. JOM. 2011; 26: 53-58.

- Smith AD, Smith SM, de Jager CA, Whitbread P, Johnston C, Agacinski G, et al. Homocysteine-lowering by B vitamins slows the rate of accelerated brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2010; 5: e12244.

- ArioÄŸul S, Cankurtaran M, DaÄŸli N, Khalil M, Yavuz B. Vitamin B12, folate, homocysteine and dementia: are they really related? Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005; 40: 139-146.

- Jung AY, Smulders Y, Verhoef P, Kok FJ, Blom H, Kok RM, et al. No effect of folic acid supplementation on global DNA methylation in men and women with moderately elevated homocysteine. PLoS One. 2011; 6: e24976.

- van der Zwaluw NL, Dhonukshe-Rutten RA, van Wijngaarden JP, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, van de Rest O, In 't Veld PH1, Enneman AW1. Results of 2-year vitamin B treatment on cognitive performance: secondary data from an RCT. Neurology. 2014; 83: 2158-2166.

- Cacciapuoti F. Lowering homocysteine levels with folic acid and B-vitamins do not reduce early atherosclerosis, but could interfere with cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013; 36: 258-262.

- Zhuo JM, Wang H, Praticò D. Is hyperhomocysteinemia an Alzheimer's disease (AD) risk factor, an AD marker, or neither? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011; 32: 562-571.