Cyclophosphamide-Associated Cardiotoxicity and Severe Cytokine Release Syndrome after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in A Child with Severe Aplastic Anemia: Case Report and Systematic Review

- 1. School of Medicine and Health Sciences, George Washington University, USA

Abstract

Background: The cyclophosphamide (Cy) based conditioning regimen is commonly used in allogeneic HSCT. Acute Cy-induced cardiotoxicity after HSCT was rare, it may progress to rapidly fatal congestive heart failure. Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) frequently complicates the immediate post-peripheral blood haploidentical Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HSCT), a small percentage of patients developed severe (grade 3-4) CRS, which was associated with a significantly higher transplant-related mortality and frequently required intensive care unit treatment.

Case presentation: We report a young child of severe aplastic anemia who received allogeneic HSCT. At days +3 after HSCT or 120 hours after the last dose of Cy, she experienced both post-transplant grade 4 CRS and Cy-associated fatal cardiotoxicity. She was admitted to the hematology intensive care unit (HCU) and treated with glucocorticoids and tocilizumab, but remained severe syndrome including fever, shock, multiple organ damage and insufficient tissue perfusion. She subsequently underwent continuous veno-venous hemofiltration combined with cytokine adsorption at day 3 of HCU, and her condition gradually improved.

Conclusion: Overall, this case highlights the critical importance of maintaining a high attention and careful evaluation of severe complications immediate post-HSCT, and timely intervention can potentially offer the survival opportunity.

Keywords

• Severe Aplastic Anemia

• Cytokine Release Syndrome

• Cyclophosphamide

• Cardiotoxicity

• Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Citation

Li H, Zhang D, Li D, Fu F, Lu D, et al. (2025) Cyclophosphamide-Associated Cardiotoxicity and Severe Cytokine Release Syndrome after Al logeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in A Child with Severe Aplastic Anemia: Case Report and Systematic Review. JSM Atheroscler 6(1): 1046.

ABBREVIATIONS

ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; BM: Bonemarrow; CRRT: Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy; CRS: Cytokine Release Syndrome; CVVH: Continuous veno venous Hemofiltration; HFNC: High-flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy; HCU: Hematological Intensive Care Unit; HSCT: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; MP: Methylprednisolone; MNC: Mononuclear Cells; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; PCT: Procalcitonin; SAA: Severe Aplastic Anemia; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; TBIL: Total Bilirubin; TCZ : Tocilizumab

INTRODUCTION

Severe aplastic anemia (SAA) is a serious blood disorder characterized by the immune system attacking the bone marrow, which results in a complete failure of blood cell synthesis. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative treatment for SAA. However, up to 30% of allogeneic HSCT recipients were still at high risk for life-threatening complications requiring intensive care unit treatment [1].

Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) refers to the syndrome of systemic inflammation, which includes fever, vascular leakage, hypotension, and multi-organ dysfunction, accompanied by high inflammatory markers and cytokine levels, IL-6 is considered the main protagonist. CRS frequently complicates the immediate post-peripheral blood haploidentical HSCT. Compared with mild (grade 1-2) CRS, patients with severe (grade 3-4) CRS had a significantly higher transplant related mortality, and a significant longer median time for neutrophil engraftment [2]. Glucocorticoid and anti-IL-6 receptor (tocilizumab) therapy was associated with alleviation of the CRS symptoms.

Cyclophosphamide (Cy) was an alkylating agent used to treat a wide range of diseases including hematological malignancies, solid tumors, and inflammatory disorders. However, the majority of CY-related cardiotoxicity cases were reported in patients received allogeneic HSCT [3,4]. The busulfan plus cyclophosphamide (BuCy) based conditioning regimen was commonly used in 53% of allogeneic HSCT [5]. Cy exhibits little cardiotoxicity at a standard doses, but substantial cardiotoxicity has been seen when given at high doses for HSCT. However, it rarely occurs in pediatric patients [6]. To our knowledge, only one case report documented standard doses Cy-related acute congestive heart failure in a 4-year-old HSCT patient [7].

Herein, we present a 11-year-old child with severe CRS and lethal acute Cy-associated cardiotoxicity after HSCT for SAA. We described the timing of appropriate use of glucocorticoids and tocilizumab as a effective therapeutic strategy for severe CRS; And we also discussed continuous veno-venous hemofiltration as a key maneuver for cardiogenic shock, especially when immunosuppressive therapy was ineffective for controlling the adverse effects of CRS.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 11-year-old girl, height: 150 cm, weight: 40 kg, with SAA presented on 14 July 2025 to our hospital for Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Haplo-HSCT) after one month of clinical cyclosporine and hematopoietic-stimulating therapy. Pre-transplant echocardiogram and electrocardiogram were normal. On 6 to 7 August 2025, she received 6.22 × 108 mononuclear cells (MNC)/kg bone marrow (BM) and 6.68 × 108 MNC/ kg peripheral blood (PB), and 1.43 × 106 CD34+ cellularity/ kg BM and 1.93 × 106 CD34+ cellularity/kg PB from her sister who was half matched donor. Additionally, she underwent Haplo-HSCT after conditioning with 2 doses of Bu (6.4 mg/kg total) on days -7 and days -6, Cy (50 mg/ kg daily, total 200 mg/kg) and antithymocyte globulin (2.5 mg/kg daily, total 10 mg/kg) on days -5 through days -2.

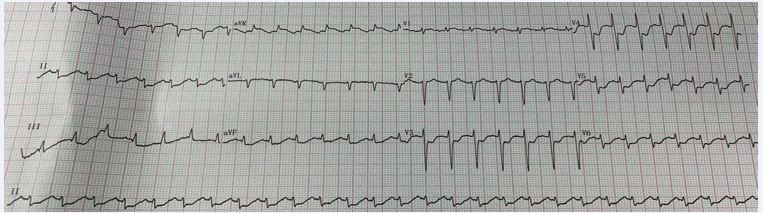

On days +3 or 120 hours after the last dose of Cy, the patient developed hypotensive shock, cold extremities and short of breath. Resuscitative fluid therapy and high dose of norepinephrine failed to alleviate these symptoms, and tachycardia, fever and syncope quickly followed. Syncope was considered to be brought on by reduced blood flow to the brain due to shock and fever. At 16:00 on August 10, the patient was admitted to Hematological intensive care unit (HCU) for aggressive vital support. The patient regained consciousness gradually. However, her condition deteriorated with unstable vital signs: listless, body temperature around 38.2?, electrocardiogram monitoring showed blood pressure 64/36 mmHg, heart rate 140 to 150 bpm, respiratory rate 30 to 35 bpm, and peripheral oxygen saturation (SPO2) 98% to 100%. The arterial blood gas analysis indicated tissue hypoperfusion deteriorated within a few hours from HCU admission: lactic acid increased from 2.5 to 9.1 mmol/L, BE decreased from -1.1 to -9.6 mmol/L, and the pH dropped to 7.33. The blood routine test revealed a reduction of complete blood cell count and neutrophil deficiency post-HSCT. Clinical laboratory tests indicated elevated Inflammatory markers: IL-6>5000 pg/ ml, procalcitonin (PCT) was 0.61 ng/ml; and multiorgan dysfunction: alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 91.8 U/L, total bilirubin (TBIL) was 122 umol/L, creatinine was 82 umol/L. The severity of the myocardial injury was noteworthy: cardiac troponin I (cTn-I) was 3489 pg/ mL, serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT proBNP) >35000pg/ml. ST-segment depression was found in leads II and V3-V6 on electrocardiography (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Electrocardiography.

Echocardiography revealed the Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 40%; Table 1

Table 1: Laboratory test results during the HCU period.

|

|

Aug. 10 |

Aug. 11 |

Aug. 12 |

Aug. 13 |

Aug. 14 |

Aug. 15 |

Aug. 16 |

Aug. 17 |

Aug. 18 |

Normal range |

|

Treatment |

MP 40mg |

MP 40mg |

MP 80mg TCZ 320mg CVVH+CA330 HFNC |

MP 80mg TCZ 320mg CVVH HFNC |

MP 80mg

CVVH HFNC |

MP 80mg

CVVH HFNC |

MP 70mg

CVVH HFNC |

MP 60mg

CVVH HFNC |

MP 50mg |

/ |

|

ALT |

91.8 |

239 |

940 |

806 |

836 |

752 |

669 |

590 |

376 |

11-66 (U/L) |

|

TBIL |

122 |

116 |

78 |

74.3 |

57.9 |

49.6 |

42 |

54.6 |

37.6 |

3-22 (umol/L) |

|

Creatinine |

82 |

73 |

123 |

135 |

106 |

114 |

91 |

86 |

89 |

<110 (umol/L) |

|

cTN-I |

3489 |

11709 |

13113 |

7113 |

5221 |

4318 |

4355 |

2915 |

2746 |

0-34.2 (pg/mL) |

|

NT-proBNP |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

>35000 |

0-300 (pg/mL) |

|

LVEF |

40 |

30 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

/ |

55 |

50-70 (%) |

|

IL-6 |

500 |

>5000 |

>5000 |

>5000 |

>5000 |

>5000 |

1544 |

549 |

97 |

0-7 (pg/mL) |

|

PCT |

0.61 |

2.23 |

6.54 |

6.12 |

4.37 |

2.4 |

3 |

1.7 |

1.36 |

0-0.3 (ng/mL) |

|

BT |

38.2 |

37.8 |

37.6 |

normal |

normal |

normal |

normal |

normal |

normal |

<37.0 (?) |

|

MAP |

45 |

67 |

88 |

92 |

74 |

74 |

77 |

75 |

70 |

>65 (mmHg) |

|

HR |

147 |

133 |

132 |

136 |

125 |

108 |

97 |

86 |

90 |

60-100 (bpm) |

|

Lactic acid |

2.5 |

9.4 |

12.2 |

5.2 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

3.7 |

1.8 |

<2 (mmol/L) |

|

Skin temperature of lower limbs |

Cold |

Cold |

Cold |

Cold |

Cold |

Warm |

Warm |

Warm |

Warm |

Warm |

|

SOFA |

8 |

9 |

11 |

10 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

7 |

5 |

0 (point) |

displays the findings. According to the diagnosis and grading system proposed by LEE for guiding treatment of CRS [8], a grade 4 CRS was identified, and methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg daily) was administered. Given neutropenic fever, imipenem, tigecycline, acyclovir and voriconazole were administrated for empirical anti-infection treatment. At 21:00, the MAP was under control above 65 mmHg after taking a combination of vasoactive medications (Norepinephrine and aramine). Nitroglycerin was given to alleviate myocardial injury. We plan to administer continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) once hemodynamic stability.

The following two days at HCU, the patient’s condition continue to worsen with liver injury (ALT 940 U/L), myocardial injury (cTn-I 13113 pg/mL), heart failure (LVEF 30%), renal injury (Creatinine 123 umol/L), and CRS manifestation such as fever, muscle pain all over the body, significant tenderness in the area of the liver, and IL-6>5000 pg/ml. Given this situation, tocilizumab (8mg/kg) were administered on day 2 and day 3 of HCU respectively, and methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg daily) was administered on day 3 of HCU. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) was administered due to pulmonary edema, dyspnea and decreased oxygenation index. On day 3 of HCU, CRRT combined with cytokine adsorption (CVVH+CA330) was initiated by evaluating her hemodynamic stability. In view of the elevated PCT (6.54 ng/ml) and liver damage, we withdraw voriconazole and tigecycline because of potential hepatotoxicity, replaced with ceftazidime avibactam, Linezolid tablets, Colistin E and micafungin.

Day 4 through day 9 in the HCU, with the infection being brought under control, the patient’s body temperature was normal, and the clinical indications improved steadily, and the LVEF recovered to nomal (55%). However, because of substantial myocardial damage, the NT-proBNP consistently remained over the detection limit (Table 1). Meanwhile, vasoactive medications decreased gradually, methylprednisolone declined quickly, and antimicrobial de-escalation. On the ninth day in HCU, the patient was transferred back to the general ward. Engraftment of neutrophils at day +15 and platelets at day +25.

DISCUSSION

We described a young child with severe aplastic anemia who received allogeneic HSCT. On days +3 post-transplant, she experienced a severe acute syndrome characterized by acute systemic inflammatory syndrome, refractory shock, multiple-organ damage, insufficient tissue perfusion and severe myocardial damage. From the perspective of the causes of shock, CRS-induced distributive shock and myocardial injury associated acute cardiogenic shock may both have played a role. Since the patient’s infection was not severe, septic shock or sepsis-induced CRS was initially ruled out. From the perspective of the causes of severe myocardial injure, cyclophosphamide-associated cardiotoxicity was the first consideration, followed by CRS. Additionally, myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury may also played a role. Throughout the first three days of HCU, even though aggressive vital support, glucocorticoid and tocilizumab were provided, the patient’s condition proceed to deteriorated, resulting in aggravation of multiple organ damage and myocardial injure. We encountered unusual treatment challenges. As a result, the timing of CRRT become essential for the recovery of organ function in cases of refractory shock and decreased tissue perfusion.

CRS syndrome frequently complicates the immediate post-HSCT. Nevertheless, there were few related studies. A single-center retrospective analysis [2], of 75 consecutive patients who received peripheral blood haplo-HCT using Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized T-cell replete. Sixty-five (75%) patients met the CRS criteria. Among them, 56 patients experienced mild (grade 1-2) CRS, and 9 (12%) patients suffered from severe (grade 3-4) CRS. Seven patients met severe CRS criteria prior to day +7. The most frequent symptoms among the 9 patients with severe CRS were respiratory failure (55.6%), hypotension (66.7%), and fever (100%). And a new cardiomyopathy was developed in one patient, the LVEF was 33% posttransplant, compared to 55% pre-transplant. Compared to mild CRS, the severe CRS cohort had a higher transplant related mortality (HR 4.59, 95% CI 1.43-14.67).

Fatal Cy-associated cardiotoxicity and acute congestive heart failure is rare in children, related reports has to our knowledge were mainly focus on adults. However, a case report [7], present histopathologie and ultrastructural examination of a 4-year-old child with fatal Cy (50mg/ kg, for 4 days) -induced cardiotoxicity after HSCT for ß-thalassemia. Results revealed extensive eoagulative necrosis of cardiomyocytes, endothelial damage, subendothelial and interstitial fibrin thrombi. Endothelial damage is the most likely pathogenesis resulting in thrombotic microangiopathy and ischémie tissue injury.

In a retrospective analysis [9], 4302 adults patients received Cy were screened, among them, 34 (0.8%) patients who received a median dose of Cy of 100 mg/kg Cy developed severe cardiac events, and were admitted to the intensive care unit 6.5 (4-12) days later. Severe CY cardiotoxicity occurred within 2 weeks following CY administration, and most of them (24 cases) had received CY in the setting of allogeneic HSCT. Eighteen (53%) patients ultimately developed cardiogenic shock, 20 (59%) patients experienced invasive mechanical ventilation,and 5 (14%) patients experienced renal replacement treatment. Sixteen patients died, among them, 12 (35%) patients died from refractory cardiogenic shock. The LVEF gradually improved in the majority of survivors, with a median time for complete recovery was 33 (12-62) days. The mainstay of treatment was supportive care, most survivors experienced an improvement or fully recovered in cardiac function within a month.

The aforementioned literatures were in line with our instance of significant myocardial injury mainly caused by Cy-associated cardiotoxicity. A median of 6.5 days for severe cardiac events indicated that close monitoring was necessary during the early post-CY administration period. Limited data existed regarding the recovery of Cy-associated cardiotoxicity [10,11], it was supposed to recover within a few days to several weeks, which matched our patient’s recovery period.

Shock and multiorgan damage associated with CRS were also significant mechanisms. The diagnostic criteria for a grade 4 CRS were based on consensus grading system for CRS [8], including continuously elevated IL-6, combination vasopressors, with grade 3-4 organ toxicity complied with the CTCA Ev4.0 standard (such as grade 3 tenderness in the area of the liver, and grade 4 heart failure, and life-threatening symptoms). Patients with grade 3-4 CRS must be closely monitored in intensive care unit with 1:1 nursing care, and should be treated with glucocorticoids and tocilizumab. Since the patient’s condition did not improve, we gave a second dose of tocilizumab and doubled the dosage of methylprednisolone (2 mg/kg daily). However, the patient’s inflammatory indicators stayed lack response to immunotherapy, it may related to ongoing production of IL-6, and severe infection activates the immune system. Therefore, it was important to promptly and effectively manage infections.

We started CRRT as soon as the patient’s hemodynamic stability with MAP above 65 mmHg after two days of HCU treatment. CRRT combined with cytokine adsorption speeded up patient recover, and successfully resolved the severe CRS crisis. First of all, contrary to immunosuppressive therapy which was ineffective for controlling the adverse effects of CRS, CRRT may ameliorated severe CRS, quickly clear cytokines and prevented the exacerbation of multiple organ dysfunction [12]. Secondly, it reduced the preload in acute heart failure, improved organ and pulmonary edema, and beneficial for controlling infections. Finally, correct metabolic acidosis continuously, and it enabled parenteral nutrition to be applied.

Our case report carried some limitations. First, there was no gold standard available for the diagnosis of Cy associated cardiotoxicity, and it was hard to quantified the contribution of CRS associated cardiotoxicity. Moreover, giving tocilizumab on the day of the fever may increase its effectiveness. Finally, importantly, cardiac function should be closely monitored in patients with severe CRS, as cardiac decompensation may not be readily evident without close observation. ICU admission should be strongly recommended in patients who develop cardiac symptoms immediately post-HSCT.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We value the integrity, precision, and hard effort put in by Dandan Li, Donyang Zhang, Jinyue Fu and Dongxue Lu in gathering the data. Haitao Li and Donyang Zhang analysed the data, Haitao Li wrote the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Haitao Li analysed the data, prepared the tables and figures, and wrote the manuscript. Haitao Li and Dongyang Zhang collected the data. All the authors reviewed the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the participant hospital (the number of ethic approval: The First Afliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University/ article/ethical review 2025, 234. Date: 2025/09). The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

the patient had signed an informed consent permitting the use of his clinical file information for research.

DATA AVAILABILITY

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

DECLARATIONS

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were performed according to the relevant guidelines and regulations.

REFERENCES

- Gournay V, Dumas G, Lavillegrand JR, Hariri G, Urbina T, Baudel JL, et al. Outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients admitted to the intensive care unit with a focus on haploidentical graft and sequential conditioning regimen: results of a retrospective study. Ann Hematol. 2021; 100: 2787-2797.

- Abboud R, Keller J, Slade M, DiPersio JF, Westervelt P, Rettig MP, et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016; 22: 1851-1860.

- Katayama M, Imai Y, Hashimoto H, Kurata M, Nagai K, Tamita K, et al. Fulminant fatal cardiotoxicity following cyclophosphamide therapy. J Cardiol. 2009; 54: 330-334.

- Mills BA, Roberts RW. Cyclophosphamide-induced cardiomyopathy: a report of two cases and review of the English literature. Cancer. 1979; 43: 2223-2226.

- Xu LP, Lu PH, Wu DP, Huang H, Jiang EL, Liu DH, et al. The proportions of peripheral blood for stem cell source continue to grow: a report from the Chinese Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry Group. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2024; 59: 1726-1734.

- Goldberg MA, Antin JH, Guinan EC, Rappeport JM. Cyclophosphamide cardiotoxicity: an analysis of dosing as a risk factor. Blood. 1986; 68: 1114-1118.

- Meserve EE, Lehmann LE, Perez-Atayde AR, Labelle JL. Cyclophosphamide-associated cardiotoxicity in a child after stem cell transplantation for β-thalassemia major: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2014; 17: 50-54.

- Lee DW, Gardner R, Porter DL, Louis CU, Ahmed N, Jensen M, et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood. 2014; 124:188-195.

- Vennier A, Canet E, Guardiolle V, Reizine F, Trochu JN, Le Tourneau T, et al . Clinical features and outcomes of patients admitted to the ICU for Cyclophosphamide-associated cardiac toxicity: a retrospective cohort. Support Care Cancer. 2023; 31: 474.

- Ishida S, Doki N, Shingai N, Yoshioka K, Kakihana K, Sakamaki H, et al . The clinical features of fatal cyclophosphamide-induced cardiotoxicity in a conditioning regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT). Ann Hematol. 2016; 95:1145- 150.

- Kamphuis JAM, Linschoten M, Cramer MJ, Gort EH, van Rhenen A, Asselbergs FW, et al. Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction of Nonanthracycline Chemotherapeutics: What Is the Evidence? JACC CardioOncol. 2019; 1: 280-290.

- Liu Y, Chen X, Wang D, Li H, Huang J, Zhang Z, et al . Hemofiltration Successfully Eliminates Severe Cytokine Release Syndrome Following CD19 CAR-T-Cell Therapy. J Immunother. 2018; 41: 406-410.