Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Fracture Healing: A Systematic Review of Prospective Clinical Trials

- 1. Department of Surgery, The University of Melbourne, Australia

- 2. Australian Institute for Musculoskeletal Science (AIMSS), The University of Melbourne and Western Health, Australia

- 3. Biomechanics and Spine Research Group, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

- 4. Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Australia

- 5. Western Clinical School, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Abstract

Background: The relationship of vitamin D status with regard to its deficiency and supplementation in the setting of fracture healing has not been well established. This review aims to evaluate the efficacy of vitamin D on clinical fracture healing

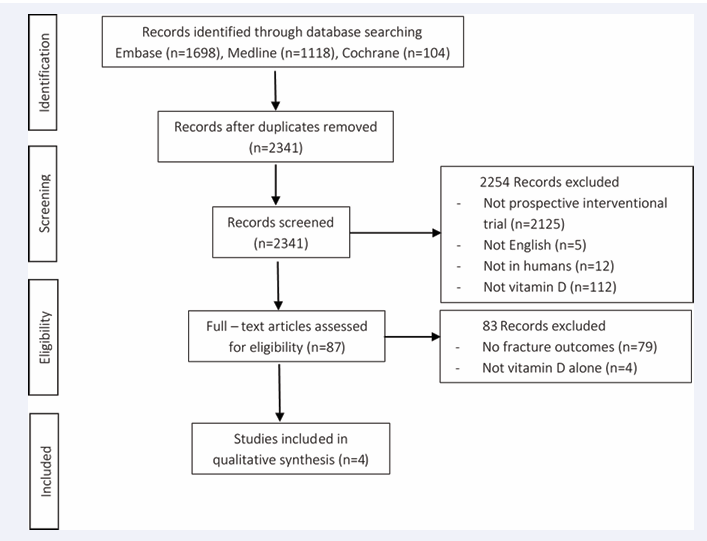

Methods: A systematic review of English articles using EMBASE, MEDLINE and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register was performed. Search terms included vitamin D, cholecalciferol, colecalciferol, hydroxycholecalciferol, calcifediol, calcitriol, dihydroxycholecalciferol, ergocalciferol, dihydrotachysterol, viosterol, 1,25- hydroxyvitamin D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 24,25-dihyroxyvitamin D, 25 hydroxyvitamin D, lunacalcipol, vitamin D3 and fracture healing or repair. Only prospective, original trials investigating vitamin D deficiency or its supplementation on fracture related outcomes in humans were included.

Results: Overall rates of delayed union in the setting of vitamin D deficiency are low. Vitamin D supplementation appears to have no effect on eventual fracture union in an adult fracture population when assessed by clinical examination and plain radiographs.

Conclusions: Prospective, interventional studies of vitamin D supplementation on fracture healing are yet to demonstrate an effect on fracture healing outcome measures.

Keywords

Fracture healing; Fracture repair; Vitamin D; Systematic review.

CITATION

Bullen ME, Pivonka P, Rodda CP (2022) Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Fracture Healing: A Systematic Review of Prospective Clinical Trials. JSM Bone and Joint Dis 3(1): 1015.

INTRODUCTION

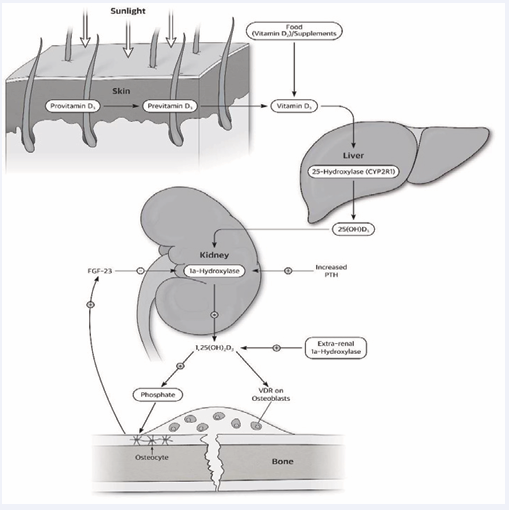

The role of vitamin D in fracture healing remains unclear. Vitamin D refers to a group of lipid soluble secosteroids, predominantly formed from irradiation of 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin in humans. The latter is metabolised to the storage form of vitamin D, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol (25OHD) in the liver, consequently 25OHD is an indicator of vitamin D stores, and is the biomarker used to determine vitamin D sufficiency from serum assays [1]. Oral supplementation, given either as a daily or periodic bolus is hydroxylated to 25OHD and stored in the liver. The active metabolite of vitamin D, 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D), is produced by both renal (endocrine function) and extra-renal (paracrine function) 1 alpha hydroxylation (Figure 1) and its primary endocrine action is to promote enterocyte differentiation and the intestinal absorption of calcium [2].

Figure 1: Role of 1, 25 vitamin D in cellular response to fracture.

Renal synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D is catalysed by the enzyme 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which is tightly regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH, the key hormone for calcium regulation) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23, the key hormone for phosphate regulation). 1-alpha-hydroxylase is also present in many extra-renal tissues and cells, including muscle and macrophages [3], however its extra-renal activity is directly related to 25OHD levels in contrast to the tightly regulated renal. Bone consists of an inorganic or mineral phase, and an organic extra-cellular matrix comprised primarily of type I collagen. The mineral phase provides resistance to compression, and the extra- cellular matrix resistance to tension. The role of 25OHD in promoting mineralization is well recognized in fracture prevention, as maximum compressive stresses reached during everyday activities such as walking are higher than maximum tensile stresses. Similarly, the strength of a healing fracture is related to the mineral content per unit of volume of callus bridging the two fragments [4].

The action of vitamin D on bone is associated with the vitamin D receptor (VDR) found in osteoblasts, osteocytes and chondrocytes [5]. Based on animal studies of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) and human studies of individuals with VDR mutations, the effects of vitamin D deficiency on unfractured bone are considered to be largely indirect, and are caused by a negative calcium balance as a result of decreased intestinal absorption [6,7]. There is no reduction in calcium absorption until there is insufficient 25OHD substrate (less than 25nmol/L) [8] for conversion to 1,25(OH)2D, with 25OHD levels above this resulting in an adaptive elevation in 1,25(OH)2D to maintain the intestinal absorption of calcium, coupled with PTH induced increased bone turnover and progressive cortical bone loss [9], resulting in rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults.

Increased fracture risk is clinically determined by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) bone mineral density (BMD) and is associated with a lower DEXA BMD. Reduced DEXA BMD and by imp-lication increased fracture risk has been reported to be associated with vitamin D deficiency in adults, although this remains controversial in children, unless they have evidence of rickets associated with severe vitamin D deficiency [10-12]. This is likely to be the result of linear growth attenuation with vitamin D deficiency in children in the first instance, reducing the amount of mineralisation required for growing bone. There is however conflicting evidence regarding the effect of vitamin D status on fracture healing. Fracture healing is a complex physiological process typically initiated in response to disruption of the cortical shell of long bones. It is essentially a form of tissue regeneration [13] and unlike other injured body tissues, results in complete healing without scarring. This process involves the differentiation of several tissues that are directly influenced by the mechanical and metabolic environment, with the primary outcome the mechanical restoration of fractured bone. Endochondral ossification occurs in the majority of fractures as part of secondary bone healing, and is a sequential process initiated by chondrogenesis resulting in soft-callus formation, which subsequently undergoes hypertrophy and mineralization. Calcium is transported into the extracellular matrix where it precipitates with phosphate to form hydroxyapatite crystals under the regulation of osteoblastic derived bone specific alkaline phosphatase to form initial mineral deposits, which are subsequently incorporated into woven bone [14].

The indirect effects of 1,25(OH)2D on fracture healing are mediated through the endocrine control of intestinal calcium absorption. The direct (local paracrine) effect of vitamin 1,25(OH)2 D at the fracture site [15] has been shown to stimulate fracture site mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts [16]. 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D also binds to vitamin D receptors (VDR) on osteoblasts at the site of the fracture callus [17], enhancing osteoblast differentiation and mineralization [18,19]. This occurs as a result of 1,25 (OH)2 D stimulation of production of mature matrix vesicles which contain alkaline phosphatase (ALP), the major enzyme involved in osteoblast mediated mineralization of osteoid (ie. collagenous bone matrix) [20].

In addition to positive in vitro effects of 1,25 (OH)2 D on fracture healing, in vivo vitamin D supplementation has also been shown to improve the mechanical strength of healing fractures in animal models of vitamin D deficiency [20,21], however other authors have shown that supplementing vitamin D sufficient rats with vitamin D does not improve radiological or histological healing of femoral fractures [22]. Inconclusive experimental animal studies are mirrored in clinical studies, and there remains a paucity of high quality prospective studies concerning the role of vitamin D in fracture healing. Two review articles have previously been published, including both animal and human studies [23,24]. At the time of their publication, there were no human trials investigating vitamin D alone. The aim of this review is to assess prospective human trials on the role of vitamin D in fracture healing.

METHODS

A systematic review was undertaken in accordance with the PRISMA statement [25]. Literature Search MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials were searched for the period from January 1974 to August 2021. Keywords and MESH terms for ‘vitamin D’ and ‘fracture healing’ were combined with filters designed to identify clinical trials. The search was limited to original research and English language publications.

Selection criteria

To be included, studies had to meet pre-specified selection criteria as follows:

1. Prospective, interventional clinical trials in humans.

2. Investigate the effect of vitamin D deficiency and / or supplementation alone.

3. Report outcome variables related to fracture healing.

Animal studies, in vitro studies, and conference abstracts were excluded. Studies that supplemented vitamin D in combination with another intervention or medication were also excluded.

Study selection

The titles and abstracts of papers were screened by author MB, and papers that did not meet all the inclusion criteria were excluded. If the abstract did not include sufficient information the full paper was obtained and evaluated. The remaining studies were evaluated as full text papers.

Data items

The primary outcome sought was assessment of fracture healing. Also collected were country of origin, study design, study population, number of subjects, 25OHD level considered to be deficient, type of vitamin D assay used and the study intervention.

Assessment of trial quality

All included papers were appraised for methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials [26]. The limited number of trials meeting inclusion criteria precluded the performance of a meta- analysis.

RESULTS

The search identified 2,920 references as a result of the database searches (Figure 2). Duplicate references were removed, leaving 2341 references for screening of titles and abstracts. We then excluded 2337 articles describing trials that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The final 4 articles met the inclusion criteria. Vitamin D deficiency was reported to be as high as 89% of adult patients presenting with long bone fractures when defined as a vitamin D level < 75nmol/L [27]. This was significantly higher than a study with a similar patient population that reported a 40% deficiency rate when considering patients with fractures of the upper or lower extremities. Of these, 11% (n=67) of patients were classified as having severe deficiency, with vitamin D levels < 25nmol/L.

Figure 2: Flow chart for identification of selected trials.

Two randomised controlled trials were found in humans. Haines et al. [27] randomised 100 patients with vitamin D levels < 75nmol/L to a single oral dose vitamin D (100,000 IU) or placebo within 2 weeks of long bone fracture. This included both operative and non-operative patients, and 3 fracture types (humeral, femoral and tibial). The primary outcome was fracture non-union. Due to lower than expected numbers of non-union, recruitment was ceased early at less than half the number needed from the a priori power calculation. No difference in union number was found at 12 months between the two groups in the cohort recruited. Heyer et al. [27] performed a randomised controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in women older than 55 years who presented with acute, non-operatively managed distal radius fractures. Participants had serum 25OHD levels measured, but were not stratified based on the results. A control group (n = 10) received no supplementation or placebo, and two intervention groups received bolus doses of either 30,000 IU (n = 11) or 75,000 IU (n = 11) oral vitamin D3 liquid at week 1-2 and again at week 6-8. BMD and microarchitectural parameters were assessed with high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT).

| Table 1: Design and characteristics of the included trials. | ||||||||

| Country | Study Design | Population | Subject Number | 25OHD Defi ciency Level | 250 OHD D Assay | Intervention | Outcome | Follow-Up |

| Netherlands | Prospec tive Co- hort | Adults with fracture of Up per and Lower Extremity | 617 | <50nmol/ L(<20ng/ml) | Roche Diag nostics Electro Chemo Lu- minescence Immuno Assay (ECLIA, modular E170) | Deficient group (n=249) supple- mented 1200IU daily for four months | No difference in radiographic union. Higher incidence of clinical delayed union in persistently deficient group 9.7 % vs 1.7 % (p=0.001) | 16 weeks |

| USA | Ran- domised Control- led Trail | Adults with long bone fracture | 113 | <75nmol/ L(<30ng/ml) | NA | Deficient group (n=100) randomized to single dose 100,000 IU oral vitamin D or placebo | No difference in clinical or radiological union | 12 months |

| Iran | Prospec- tive Co- hort | Elderly Inter- trocantaric femoral frac tures | 100 | Below normal laboratory range | NA | Normal vitamin D levels (n=50) vs vitamin D deficient (n=50). All supplimented 50,000 IU vitamin D bolus | Improvement in clinical union at 4 and 8 weeks in deficient group. No difference clinical union 12 weeks. No difference radiological union | 12 months |

| Netherlands | Ran- domised Control- led Trail | Women > 50 years old | 32 | Groups not allocated based on 25OHD levels | Chemo lumi- niscence Im- munometric assay-DSiSYS Instrument (immunodiag- nostic system, PLC) | Control group (n=11), low dose group (700 IU 6-weekly; n=10),high dose (1800 IU 6-weekly; n=11) | No differences between control and low dose group. High dose group had de creased trabecular number and lower compression stiffness | 12 months |

Trabecular density and total density increased in all groups at the six week follow-up, then decreased at the twelve week follow-up. No differences were found between the control group and the low-dose supplementation group when assessing the fractured wrist for BMD and other bone parameters. When comparing the control group to the high-dose supplementation group, decreased trabecular number and increased trabecular separation were seen, as well as decreased compression stiffness. There were no differences in serum markers of bone resorption (CTX) or formation (PINP) between the control and intervention groups at twelve weeks. However there was an increase in the marker for bone resorption in the high-dose supplementation group compared to the control group at the 3-6 week follow-up. Another recent, non-randomised trial in elderly patients with neck of femur fracture recruited 50 patients with ‘normal’ vitamin D levels, and 50 patients with ‘low’ vitamin D levels, although these levels were not defined. All participants received 50,000 IU vitamin D, with the deficient group subsequently receiving another 50,000 IU bolus every 12 weeks post-operatively. No difference in radiological fracture healing was shown within 8 weeks of follow-up. However a clinical improvement in fracture healing at this time point in the vitamin D deficient group was observed [28].

| Table 2: Risk of bias assessment. | |||||||

| Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants / personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias | |

| Gorter 2017 | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Haines 2017 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Behrouzi 2018 | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear |

| Heyer 2021 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

A similar study design was employed by Gorter et al. [29] in 2017. They recruited 617 patients with a fracture of their upper or lower limb, and supplemented those with vitamin D deficiency (40 %) with 1200 IU vitamin D daily for four months. A clinical delayed union was only described in six patients. Significantly more clinical delayed unions at four months were observed in the group who remained deficient following supplementation (9.7 %) versus those with vitamin D sufficiency post supplementation (1.7 %) and those with sufficient vitamin D levels on presentation (0.3 %) p<0.001. They found no significant difference in radiological union at 16 weeks between groups in those that were still being followed up.

DISCUSSION

Vitamin D status has long been of interest in fracture healing, with a number of recent studies evaluating the effect of supplementation on fracture healing in vitamin D deficient populations. Significant variation in vitamin D thresholds used to define deficiency was seen across the studies, with one included study not listing any values for deficiency [28]. Comparison between these studies is therefore difficult without raw data. This mirrors clinical practice, with contention even within the same geographic areas. The level generally accepted to represent deficiency is vitamin D < 50nmol/L [30], however an international consensus on vitamin D thresholds would facilitate research in the area, by enabling valid comparisons of published clinical trials. There are also many different vitamin D assays used across studies, which produce different results, and the assay manufacturer details are often not reported [31]. Measurement of both 25OHD and 1,25 (OH)2 D in clinical settings most commonly utilises automated immunoassays, due to ease of use and cost. However these are recognised to have reduced accuracy and specificity [31]. The “gold standard” for vitamin D assays utilise liquid chromatography tandem mass spectroscopy (LC-MSMS) systems. Standard reference materials have been developed, although with limited application [31]. Improvements in accuracy and comparability of results are essential to not only build reliable evidence on the topic, but to enable better treatment decisions. Dietary calcium intake is also inconsistently considered, particularly in human studies.

The randomised controlled trial by Haines et al. [27] calculated on a priori sample size of 420 patients per group. However only 50 patients per group were recruited after the low non-union rate resulted in early cessation of the study. Two cases of non-union following long-bone fractures were found in both the control and supplementation groups. As such although no difference in non union rate was reported, this may not represent a true result, due to the small numbers of study participants. This study also used relatively blunt outcome measures of union, namely plain radiographs and clinical assessment. Thus the study was not able to provide conclusions regarding time to union or callus strength, which may have clinical relevance.

Heyer et al. [27] performed a randomised controlled trial using HR-pQCT to assess fracture healing, a modality previously shown to be viable for assessing fracture healing [32-34]. This study showed an unexpected detrimental effect of high-dose 25OHD supplementation on trabecular number and trabecular separation, as well as decreased compression stiffness compared to the control group. This may be partially explained by the significantly lower total BMD in the high-dose group at baseline compared with control, which may cause more bone to be assessed as outside the threshold set for mineralised tissue. This was adjusted for in statistical analysis, although potentially indicates inadequate sample size. There was also a difference in severity of fracture between groups, with only one patient in the control group requiring reduction, compared with five in each intervention group. The study population evaluated in this trial may be considered vitamin D sufficient, with the average serum 25OHD 60nmol/L, although 33% of the overall cohort was less than 50nmol/L. This relatively normal 25OHD level may reduce the effect of vitamin D3 supplementation; however 90% of participants in the high-dose group were less than 75nmol/L, and 60% within the low-dose group.

The distal radius poses a number of difficulties for densitometric imaging. Osteoporotic fractures of the distal radius typically comprise an element of axial compression, with resultant shortening of fragments. This may counter-intuitively increase BMD measurements at the fracture site. It also makes identifying and thus analysing fracture callus alone difficult. The method used by Heyer et al. scanned an 18mm region in the same location for each participant. This region was averaged for quantitative analysis, and likely included regions of unfractured bone. The reported decrease in BMD in this region over the study period may therefore be attributable in part to disuse osteopaenia, rather than being solely related to fracture healing. The impact of this would be dependent on the individual fracture pattern.

Gorter et al. [29] also reported low non-union rates. This prospective cohort study compared the differences in union between those that remained vitamin D deficient post supplementation, and those that were sufficient post supplementation. As all participant received supplementation, serum vitamin D levels were compared rather than the effect of supplementation itself. This study also reflects the imperfect biochemical success of supplementation, with 21.3% of participants remaining deficient. They found more delayed unions in the vitamin D deficient group that remained deficient post supplementation, although there were only 6 non-unions out of the 249 participants found to be vitamin D deficient. Delayed union was determined from retrospective review of medical records, and was only registered when written as such, without standardised examination or recording procedures. Another weakness of the study was that the four month follow up period was only for those still being seen at the clinic, which only represented 13% of the original cohort, and included patients who may have still been followed up for reasons other than delayed union. They concluded there was no significant difference in radiological union at 16 weeks between groups in those that were still being followed up.

A number of studies outside the inclusion criteria of our literature search help to guide understanding of the role of vitamin D. Studies that combined vitamin D supplementation with another intervention were excluded from this review because of the inability to attribute the effect of a combined intervention to any single component, particularly with regard to calcium supplementation. Despite this, there were two relevant clinical trials which warranted additional review. Doetsch et al. [35] examined the effect of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on proximal humerus fracture healing in osteopaenic or osteoporotic females. The majority of participants were vitamin D deficient, with the mean 25-OH vitamin D level in the active group 39±16nmol/L, and 40±21nmol/L in the placebo group, although participants with vitamin D levels greater than 50nmol/L were included in both groups. DEXA scanning of the fracture site showed a significant increase in fracture site BMD in the active group.

The disadvantage with this method is the inability to differentiate fracture callus density and intact cortical bone density changes. The second trial by Kolb et al. [36] within the time frame of this review also used a combination of calcium and vitamin D supplementation, in the setting of distal radius fractures in post-menopausal women. This was essentially a vitamin D deficient population, with 83.5% of participants being deficient (as defined below). All patients were managed with a combination of percutaneous K-wires and external fixation, and the entire cohort was supplemented with calcium and vitamin D for 6 weeks post-operatively. No difference was seen in the fracture callus area at 6 weeks between patients with vitamin D levels less than 50nmol/L, those 50 to 75nmol/L or greater than 75nmol/L on presentation [36]. All patients had surgical intervention consisting of K-wire and external fixation, and received the combined supplementation.

Peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) was used to assess fracture site BMD at six weeks, and found no association between vitamin D levels and fracture BMD. Longitudinal pQCT assessments were not possible because of the presence of metalware at the two and four week follow up points, with metalware removed before the six week scan [36]. An inherent weakness of studies requiring daily supplementation, rather than using a single bolus dose, is the risk of decreased patient adherence with supplementation. Measurement of compliance in studies using daily supplementation is difficult, with supervised administration being costly and impractical.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Despite the established interest in the role of vitamin D in fracture healing, the heterogeneity of study design and inconsistent results to date do not currently support vitamin D supplementation to optimise fracture healing. Overall, there is a lack of high quality trials investigating the effect of vitamin D on fracture healing, with conflicting evidence obtained from human studies. In order to make studies comparable, standardised vitamin D assays are required for the diagnosis of defiency and the evaluation of treatment. Standardised, accurate outcome measures of fracture healing are also needed, and volumetric imaging modalities warrant further investigation to this end.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Evelyn Hutcheon, Western Health librarian, for assistance with the literature search. We acknowledge Emily Galea for the creation of Figure 1.