Rhabdomyolysis, Adverse Event Associated With the Concomitant Use of Pregabalin and Atorvastatin: A Case Report

- 1. Químico Farmacéutico, Unidad de Farmacia, Hospital El Pino, Chile

- 2. Médico Internista, Unidad de Paciente Crítico, Hospital El Pino, Chile

Abstract

Rhabdomyolysis is a complex condition caused by damage or injury at the muscle level, which can generate complications at the level of multiple organ systems. The clinical presentation of this entity is variable, but creatine kinase levels are the most sensitive test for diagnosis. Among the most important causes of rhabdomyolysis is the use of drugs, among which statins stand out and pregabalin has recently been described as one of the pharmacological causes. The evidence of this adverse event is scarce at international level, with 4 case reports of rhabdomyolysis associated with pregabalin, 2 of them presented in patients using statins. It should be considered that the evidence of this adverse event is null at the national level. We present the clinical case of a 73-year-old patient, a chronic statin user who presented myalgia associated with the recent incorporation of pregabalin to his pharmacological therapy.

KEYWORDS

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Pregabalin

- Statins

- Adverse reaction

CITATION

Gabriel Arias C, Susana Madrid M, José Valderrama C, Ignacio Aravena O (2025) Rhabdomyolysis, Adverse Event Associated With the Con- comitant Use of Pregabalin and Atorvastatin: A Case Report. JSM Clin Case Rep 13(1): 1256.

INTRODUCTION

Rhabdomyolysis is a complex condition caused by a severe muscular injury or damage. It involves the releasement of cellular components towards the bloodstream, such as myoglobin, creatine kinase (CK), aldolase, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), as well as electrolytes, which might produce possible complications in different systems [1,2]. Rhabdomyolysis varies from an asymptomatic pathology with elevated CK to a life- threatening condition, associated with elevation of extreme CK values [2].

Some complications associated with this condition may result in electrolyte imbalances, acute kidney injury (AKI), elevated transaminases, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Even though rhabdomyolysis is usually a product of direct traumatic injuries, this condition can be caused by medication, toxins, infections, muscle ischemia, metabolic disorders, prolonged efforts or rest, and induced hyperthermia states such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and malignant hyperthermias. The clinical presentation, including massive necrosis, is manifested as muscle weakness, myalgia, swelling, and commonly, pigmenturia without hematuria [2,3].

The clinical presentation differs, and more than 50% of the patients do not report pain or muscle weakness. The elevation of CK levels is the most sensible laboratory test to evaluate muscular injury that has the potential to cause rhabdomyolysis. CK values > 5000 IU/L may be correlated with kidney injury. It has been stablished that for considering identifying a patient presenting rhabdomyolysis, he must present a substantial increase in CK at least 11 times the upper limit [2].

Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors) are the most associated drugs with rhabdomyolysis when used alone or in combination with other drugs. Some drugs that cause this condition are statins, fibrates, barbiturates, cyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, among others [3].

Pregabalin has a similar structure to gamma- aminobutyric acid (GABA), with a similar structure to gabapentin. Pregabalin presents analgesic, anxiolytic and antiepileptic properties. Despite being similar to GABA, Pregabalin does not exhibit GABA-mimetic effects; However, it results in an increase in neuronal levels of GABA and generates a dose- dependent activity of glutamic acid decarboxylase [3,4,5].

Pregabalin is excreted unaltered in urine (90-98%) with clearance proportional to creatinine clearance in patients not receiving hemodialysis (HD), for this reason, dose adjustment is required in patients with renal dysfunction [3,5].

Among the main adverse effects associated with the use of pregabalin, central nervous system depression, dizziness and drowsiness stand out. Additionally, other adverse effects have been reported, such as angioedema, peripheral oedema, dry mouth, blurred vision, weight gain, difficulty concentrating and hypersensitivity, and very isolated cases of rhabdomyolysis [3].

Cases of rhabdomyolysis associated with the use of pregabalin in patients with neuropathic pain have been described in pre-marketing studies, in which 0.8% of patients were reported to present an increase of CK, in contrast to the 0.4% with placebo. In patients treated with pregabalin for the management of post-herpetic neuralgia, CK elevation was reported to be 0.6% versus 0% in the placebo group. When combining the studies, the pregabalin group had an increase of 3 times the value of the upper limit of CK [3]. Additionally, values of CK ≥ 1000 IU/L were reported in 0.7% of patients in the pregabalin group versus 0.3% in the pregabalin group placebo. This represents at least double the risk in patients with active treatments [3].

To date, only 4 reports associated with secondary rhabdomyolysis due to the use of pregabalin have been published, in two cases the concomitant use of pregabalin and statins is reported. Currently, there is no suggested mechanism that could explain the interactions between these medications, although it is believed that there may be an increase in the concentration of statins due to inhibition of the metabolic pathway associated with CYP 450 in its 3A4 isoform [3,5,6].

Additionally, besides those publications, there is a report on secondary rhabdomyolysis associated with pregabalin in Argentina in 2016. A relevant antecedent concerning this case is the presence of deterioration in renal function prior to the event, as a result, the accumulation of this drug would be a factor that contributes to generating this type of adverse reactions [6].

Unfortunately, in Chile there are no case reports associated with this event, therefore, the treatment and prognostic for this patient is not clearly established.

For this reason, in this paper we present a clinical case report of a patient who begins his treatment with pregabalin and develops rhabdomyolysis, requiring hospitalization in a Critical Patient Unit (CCU). Given that there are no national records of this adverse drug reaction (ADR), it is proposed to analyse this case to provide information regarding possible complications and treatment of secondary events associated with the use of pregabalin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reference Research

Bibliographical research was done considering national and international databases, such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Scielo, and Revista Chilena de Medicina Intensiva, selecting publications dated from 2000 to 2024. Keywords in Spanish and English language were applied, such as “pregabalina”; “pregabalin”; “estatina”; “statin”; “rabdomiólisis”; “rhabdomyolysis”;” miopatía”; “myopathy”, “reacción adversa a medicamentos” y” adverse drugs reaction”.

Description of the clinical case background

With the aim of describing meticulously the background of the clinical case report, data associated with these parameters were included (Annex N°1):

- Pharmacological profile: previously used drugs, dosage, pharmaceuticals forms, pharmaceutical drugs used during hospitalization.

- Clinical background: comorbidities, reason for admission, signs, symptoms, complementary images and laboratory tests.

- Temporal Correlation: Establish the start and end periods of pharmaceutical drugs associated with the pathology or comorbidity.

Causal Analysis

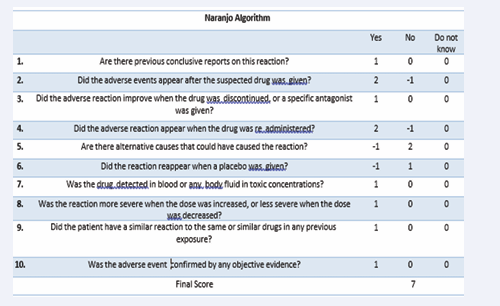

To determine the causality of the ADR, Naranjo algorithm (Annexe N°2) was employed, classifying it according to the following categories: definitive ADR, probable ADR, possible ADR or doubtful ADR [7].

RESULTS

The publication of the following clinical case is expected to establish an evidence-based regarding this low-incidence adverse event. In this case, the patient’s history will be presented, along with laboratory tests and clinical evolution.

The patient consists of a 73-year-old patient with history of high blood pressure (HBP), heart failure (HF), 5 previous infarctions with installation of 2 coronary stents and coronary revascularization in 2018. As an outpatient, he used losartan 50 mg every 12 hours orally (PO), carvedilol 6.25 mg every 12 hours PO, acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg every 24 hours PO, atorvastatin 80 mg every 24 hours PO since approximately 2018, furosemide 40 mg every 24 hours PO, and another unspecified diuretic.

Indirect Anamnesis

The patient had a previous hospitalization and was admitted to the Emergency Department due to a syncopal episode vs lipothymia, accompanied by vomiting, dyspnea, and a history of paresis in the right upper extremity (RUE) and right lower extremity (RLE). In this context, the patient was admitted under a diagnosis of Syncope with cardiogenic observation due to 1st degree atrioventricular block evidenced in the admission electrocardiogram. Table 1 displays the exams of this hospitalization.

Table 1: Laboratory Exams Indirect Anamnesis

|

Laboratory Test |

ED Admission |

IMCU Admission |

Medicine Admission |

HITH Admission |

|

Hemoglobin |

12.3 g/dL |

11.2 g/dL |

- |

10.3 g/dL |

|

TTUS |

25.7 pg/mL |

33 pg/mL |

- |

- |

|

DD |

23.52 mg/L |

- |

- |

- |

|

INR |

1.02 |

1.07 |

1.06 |

- |

|

TTPa |

21 seconds |

24 seconds |

- |

- |

|

CK-MB |

23 UI/L |

- |

- |

- |

|

CK-T |

90 UI/L |

- |

- |

- |

|

Crea |

1.53 mg/dL |

1.47 mg/dL |

1.38 mg/dL |

1.21 mg/dL |

Subsequently, it was decided to transfer the patient to the Intermediate Medical Treatment Unit (IMCU) where, due to compromised conscience, he was evaluated by Neurology and was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack (TIA) because of the duration of the patient’s clinical condition. An imaging study was performed that ruled out ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) involvement. Once clinical stability was achieved, it was decided to transfer the patient to Medicine where a complete urine proteinuria study was performed, requesting an immunological profile and images. In addition, neurology follow-up continued, and the patient was discharged with Enalapril,10 mg 1 tablet every 12 hours PO permanently; Atorvastatin 40 mg 2 tablets per day PO permanently; Clopidogrel 75 mg 1 tablet per day PO permanently; Acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg 1 tablet per day PO permanently; Levothyroxine 100 mcg ½ tablet a day PO, take in the morning on an empty stomach; and Paracetamol 500 mg 2 tablets every 8 hours PO for 10 days. Upon discharge, he was transferred to home hospitalization (HITH) to monitor plasma electrolytes, kidney function and anti-phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R) antibody. During hospitalization, the patient reported neck pain, hence the treating physician indicated the use of pregabalin 75 mg every 24 hours PO on the night starting on October 2, 2024.

Current Hospitalization

The patient, with the previously described medical history, presented hospitalization in October 2024 in the ED of Hospital El Pino for a transient ischemic attack (TIA), evaluated by neurology that indicated double antiplatelet aggregation. In addition, alteration in urine proteins was examined to identify a possible nephrotic syndrome. Tests were taken to rule out autoimmune diseases, resulting negative. The patient was discharged and entered outpatient follow-up by nephrology to study the causality of nephrotic syndrome.

The patient was admitted to the emergency department on 11/8/2024 due to a clinical picture of 3 days of evolution characterized by compromised general condition, myalgia, joint pain, neck pain and urinary retention. Admission tests revealed creatinine up to 7.5. A diagnosis of Oliguric AKI KDIGO III acute renal failure was made, with no response to medical management with rising nitrogen and refractory metabolic acidosis, hence he was transferred to CCU for evaluation of initiation of renal replacement therapy. A Computed Tomography (CT) Scan without contrast was performed (11/8/24) which displayed no lithiasis or hydronephrosis, only a bilateral hypodense renal lesion that could not be characterized without contrast. In laboratory tests taken on 11/12/24, CK-total was found to be 56947 IU/L, leading to the diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis as the cause of kidney failure. Prior to hospitalization, the patient was being studied for nephrotic syndrome, which was ruled out as being an autoimmune disease, hence the development of rhabdomyolysis is associated with pharmaceutical drugs. It is suspected that the concomitant use of atorvastatin and pregabalin triggered this condition. The patient was prescribed pregabalin on 10/2/24 and had been taking atorvastatin since 2018.

Due to the suspicion of ADR, on 12/11 nephrotoxics and suspected drugs were suspended, and 3 boluses of 500 mg of methylprednisolone were prescribed. On day 13/11 he was evaluated by a nephrologist, and CVVHDF (continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration + heparin) was decided, starting the same date, since there was no response to treatment with diuretics. During connection to the machine, there was an episode of hypotension, desaturation and hypothermia, compatible with septic discharge with suspected urinary tract infection, and ampicillin/sulbactam + amikacin was administrated. 48 hours of CVVHDF were completed but the system coagulated, hence it was disconnected from it.

Subsequently, expectant management was maintained (no replacement renal therapy was required), and diuresis was forced with positive results. The patient progressed with improvement in urinary output and with low nitrogen levels, resulting an impressive improvement in renal function, and with rhabdomyolysis in frank regression reaching CK values of 232 IU/L. For these reasons, expectant nephrological management was decided, without the need for any type of renal replacement therapy. The management of furosemide was maintained, requiring frequent loads as the patient evolved polyuria with low potassium values. On 11/23 it was decided to start hemodialysis only for goals that were not required (to maintain negative BH). The summary of the exams is available in Table 2.

Table 2: Laboratory Tests under Hospitalization

|

Laboratory test |

12/12 |

13/12 |

14/12 |

15/12 |

16/12 |

17/12 |

18/12 |

20/12 |

22/12 |

23/12 |

24/12 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) |

10.4 |

10.5 |

5.32 |

3.13 |

1.76 |

2.05 |

3.35 |

4.04 |

3.25 |

3.1 |

2.78 |

|

BUN (mg/dL |

140 |

151 |

90 |

57.9 |

27.2 |

29.8 |

57.9 |

89 |

94.1 |

91.6 |

84.6 |

|

Total CK (UI/L) |

56947 |

46733 |

35230 |

18939 |

8662 |

3332 |

1666 |

611 |

347 |

336 |

232 |

|

BT (mg/dL) |

0.57 |

0.47 |

0.68 |

0.62 |

0.66 |

0.75 |

0.59 |

0.46 |

- |

0.51 |

- |

|

BD (mg/dL) |

0.47 |

0.36 |

0.55 |

0.41 |

0.47 |

0.36 |

0.28 |

0.4 |

- |

0.41 |

- |

|

BI (mg/dL |

0.1 |

0.11 |

0.13 |

0.21 |

0.19 |

0.39 |

0.31 |

0.06 |

- |

0.1 |

- |

|

FA (UI/L |

575 |

614 |

586 |

495 |

457 |

444 |

393 |

427 |

- |

432 |

- |

|

GOT (UI/L) |

1772 |

1674 |

1337 |

1037 |

905 |

644 |

427 |

260 |

- |

173 |

- |

|

GPT (UI/L) |

559 |

561 |

607 |

510 |

491 |

415 |

339 |

293 |

- |

243 |

- |

|

GGT (UI/L |

916 |

925 |

911 |

799 |

798 |

890 |

824 |

909 |

- |

857 |

- |

|

INR |

1.12 |

1.17 |

1.11 |

1.16 |

1.12 |

1.02 |

1.04 |

1.1 |

- |

- |

1.02 |

|

TP (seconds) |

13.9 |

14.5 |

13.8 |

14.4 |

13.9 |

12.8 |

13 |

13.7 |

- |

- |

12.7 |

|

TTPa (seconds) |

26 |

27 |

26 |

34 |

33 |

23 |

23 |

- |

- |

- |

22 |

|

Haemoglobin (g/dL) |

10.6 |

10.6 |

10.7 |

10.1 |

9.9 |

9.0 |

8.9 |

8.0 |

7.3 |

7.3 |

7.5 |

|

Haematocrit (%) |

30.3 |

31 |

29 |

27.6 |

27.8 |

25.5 |

25.1 |

22.9 |

21.2 |

21.2 |

22.2 |

|

Leukocytes (x103 mm3) |

10.4 |

9.1 |

21.7 |

18.8 |

17.1 |

13.3 |

14.5 |

10.5 |

8.8 |

8.8 |

7.5 |

DISCUSSION

There are pre-marketing reports of CK elevation associated with pregabalin, although details are not provided. There are several reports of CK elevation in clinical trials associated with pregabalin, these cases being < 1% in patients using this medication [3,4].

In 2011, a study was published whose objective was to describe the medications with the greatest prevalence of rhabdomyolysis according to the database presented in Food and Drug Administration where pregabalin is presented as the 37th drug related to this condition [3].

Although there are few case reports of ADR associated with pregabalin and its relation with the production and/ or incidence of rhabdomyolysis, there are international investigations that have addressed this possibility, as described in an article by Gunathllake et al. [6]. The aforementioned publication presents the case of a 66-year- old patient treated with pregabalin at a dose of 75 mg every 12 hours PO for the management of trigeminal neuralgia, and atorvastatin at a dose of 40 mg every 24 hours for 5 years. The patient presents a picture of muscle weakness in the upper and lower extremities, with a clinical study without suggestion of neurological alterations, with oliguria and myoglobinuria, and CK values of 14050. IU/L.

Additionally, Kaufman and Choy [4] present acase report of a patient undergoing treatment with statin (simvastatin 20 mg daily recent start) plus pregabalin, previously used with a dose increase from 50 to 100 mg every 8 hours PO. The report presents a table of rhabdomyolysis with CK values that reached 14,191 IU/L, which did not decrease upon suspension of simvastatin as the first suspected drug and decreased after discontinuation of pregabalin with the following CK levels at 4605 IU/L.

Subsequently, in 2024, Wenjing Zhai et al. [5], presented 4 cases of study (2 of them were already introduced), two cases displayed rhabdomyolysis secondary to monotherapy with pregabalin, while the rest were in combination with statins.

Although case reports have been presented in relation to this adverse event, the mechanism by which it occurs is not well described, in some cases, possible interactions are proposed suggesting interference with the renal elimination of hydrophilic metabolites of statins (mentioned in the reference as simvastatin). Furthermore, statins are cytochrome-dependent drugs for their metabolism, evidenced in cases of statin-induced myopathy when there is concomitant use of medications that interfere with the Cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme. However, pregabalin has minimal hepatic metabolism and does not induce or inhibit the cytochrome system [5,6]. Some research suggests that pregabalin induces a sustained elevation in the concentration of cytosolic calcium and a reduction in the content of Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) at the myoplasmic level, which can lead to muscle toxicity. Hence, this mechanism needs to be investigated in the future [4].

To identify causality associated with pharmacological interaction Naranjo algorithm was employed for the ADR report. It presented a score of 7, giving a result of probable ADR, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Naranjo Algorithm

Therefore, the ADR report was made known to the Instituto de Salud Pública (Institute of Public Health).

CONCLUSIONS

Rhabdomyolysis secondary to medications is an entity that can generate several complications in patients. Therefore, it is important to identify this adverse reaction, especially when it is secondary to medications that do not present this event on a regular basis, such as pregabalin. Hence, Naranjo algorithm is used to evaluate the probability of occurrence of an adverse reaction according to the patient’s clinical status and gives a causal result. When the score is 9 or greater this means that the ADR is highly probable for the drug, 5-8 means that it is probable, 1-4 is possible, and zero is unlikely. When applying this scale to the exposed clinical case, a value of 7 resulted, resulting in a probable ADR to pregabalin.

REFERENCES

- Kodadek L, Carmichael SP, Seshadri A, Pathak A, Hoth J, Appelbaum R, et al. Rhabdomyolysis: An American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Critical Care Committee Clinical Consensus Document. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2022; 7: e000836.

- Torres PA, Helmstetter JA, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Rhabdomyolysis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. PubMed. 2015; 15: 58-69.

- Medellin MAS. Rabdomiólisis por pregabalina. Caso clínico y revisiónde la bibliografía. Revista Argentina de Terapia Intensiva. 2016; 33: 1.

- Kaufman MB, Choy M. Pregabalin and simvastatin: first report of a case of rhabdomyolysis. PubMed. 2012; 37: 579-595.

- Zhai W, Liu H, Li J, Xin H. Pregabalin-induced rhabdomyolysis: a case series and literature analysis. J Int Med Res. 2024; 52

- Gunathilake R, Boyce LE, Knight AT. Pregabalin-associated rhabdomyolysis. Med J Australia. 2013; 199: 624-625.

- Formación Sociedad Española de Farmacia Hospitalaria. (s. f.).