The Climate Challenge to Indigenous Mbororo Communities in the Mbum Plateau, North West Region, Cameroon

- 1. Department of Geography, Faculty of Social and Management Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon

- 2. Department of Geography and Planning, Faculty of Arts, the University of Bamenda, Bamenda, Cameroon

Abstract

The study examines the impact of climate change on the Mbororo people’s way of life in the Mbum Plateau of Cameroon. Both primary and secondary data were utilized in the research. The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) was employed to evaluate the vulnerability of the rangeland ecology to climate variations, utilizing rainfall and temperature data from 1981 to 2022. Primary data sources included field surveys and interviews with 200 households, complemented by secondary sources from published and unpublished materials. The qualitative presentation involved content analysis, integrating different opinions and perceptions of the informants with the presentation of results. The quantitative analysis involved the graphic presentation of climatic data and a tabular presentation of dwindling pasture resources. The findings indicated that rainfall has become more unreliable in the Mbum Plateau, while temperatures are rising, posing a significant challenge to the Mbororo pastoralists as the rangeland ecological resources for their cattle are decreasing. To adapt to the diminishing cattle numbers, the Mbororos have taken up farming, hawking, and schooling as new means of livelihood. The study recommends sustainable pastoral activities by encouraging the introduction of drought-resistant cattle species, as well as bracharia and guatemala grass to supplement natural pasture. It also suggests that MINEPIA should regularly control herd size to maintain ecological balance and that transhumance tracts and areas should be demarcated to avoid frequent farmer-grazier conflicts and cattle theft.

Keywords

- Adaptation

- Challenges

- Climate Variability

- Mbororo

- Sustainable Development

CITATION

Awudu N, Tume SJP, Ngwa FG, Nkuh YR (2024) The Climate Challenge to Indigenous Mbororo Communities in the Mbum Plateau, North West Region, Cameroon. JSM Environ Sci Ecol 12(1): 1092.

INTRODUCTION

Global population growth is slightly over 8 billion. Most of these populations live in Africa and Asia, pushing the ecological carrying capacity to its limit and to an extent far beyond human production and consumption patterns. Despite this ever-growing population, development endeavours seem to have been tilted more toward solving the effects caused by this ever-growing population rather than handling the causes. It has been predicted that ? of the world’s population will be living in cities by 2050 and 90% of the urban population will be in Africa and Asia. African Policy Circle (2020), in addressing the challenges of urbanization in Africa and providing policy discussions noticed that most efforts today by national and international development initiatives in rural development have put more measures to improve livelihoods, create jobs and to an extent, reduce rural exodus which to them seems to have been jeopardizing the already rural livelihoods [1]. The efforts of these development initiators in rural areas have resulted in the expansion and intensification of agricultural production (crops and livestock) which supply food to the growing urban dwellers. With these great strides towards development, the initiators seem to have driven the efforts towards the wrong direction and ignored the real needs of the local population including the Mbororo communities of the Mbum Plateau. Population growth in most parts of West and Central Africa is associated with rising demands for vegetables, food crops, and animal products, and providing job opportunities to the local people is becoming a great challenge in recent times. In Mbum Plateau where cattle rearing remains an important livelihood of the indigenous Mbororo, competition over dwindling rangeland resources between them and the local crop farmers is, increasing land conflicts because the aerial coverage of grass for cattle has greatly dwindled. This is seriously threatening the livelihoods of the Mbororo communities at a time when the climate keeps on fluctuating besides dwindling water points [2- 4] and rangeland [5-7]. The Mbororo who used to be pastoral nomads have today become sedentary cattle breeders. With this challenge in their living styles, they have been confronted by the Local Wimbum people who see them more like “strangers”. The fluctuating climate has brought about the emergence and re- emergence of livestock diseases in the plateau. The increasing land conflicts in the Mbum Plateau between the Wimbum and Mbororo communities have greatly threatened them [8-11]. If these issues have to be resolved, the authorities charged with managing climate, rangeland and surface water resources need to develop a more sustainable option.

The Mbum Plateau has noticed an alteration in its environmental components affecting the Indigenous Mbororo. Livestock rearing which remains the main sustenance of the Mbororo is today facing many challenges. The rangeland where the Mbororo people practice their activities has witnessed changes in vegetation, water availability, climatic fluctuation, and an increasing population that cultivates it for crop production. Over the years, the Mbororo have changed the ways they use to operate. This change seems to have coincided not only with the changes in cattle reduction but also with some significant socio- economic transformations in their lifestyle. To modernize, some have constructed modern houses; others are into crop farming, while some have migrated to towns to take alternative economic activities. Those into crop activities are facing the eminent problem of land tenure with no direct access to the land. The growing numbers of Mbororo without cattle over the years in the Mbum Plateau in the midst of reducing rangeland as a result of sedentarisation on their side and construction of permanent settlements where only temporal structures are permitted poses many problems. The change of Mbororo livelihoods from pastoralism to sedentary seems to have caused many land use conflicts in the Mbum Plateau. Population growth is expected to be accompanied by economic and social policies that circumvent problems such as shortages in social amenities. Between 1987 and 2022, the Mbum Plateau witnessed population growth from 105,547 to 112,241 (Nkambe and Ndu Councils, 2022). Today there are increased climatic fluctuations, land use conflicts, permanent settlements in range land and increasing crime, dwindling water points, pastureland, health facilities and poor road network, especially in the Mbororo communities of Mbawgong, Binka, Ntamru, Ntumbaw, Ntiso, Mangu and Mbajeng. This study, therefore, set out to assess the spatial Indigenous Mbororo challenges and sustainable development options in the Mbum Plateau improving the quality of their lives. These identified lacunae need to be addressed, if forward-looking plans could be introduced to coordinate multiple sectors within the Mbororo communities, in the face of climatic fluctuation, increasing population, and land use conflicts in the range of land beside the changing lifestyles observed in Mbororo communities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

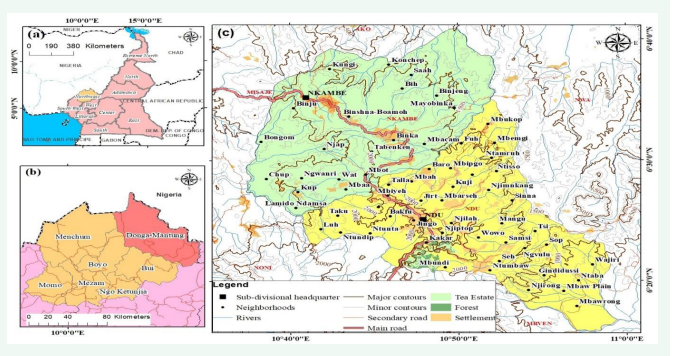

The Nkambe Plateau lies between Longitudes 10°50´48´´ east of the Greenwich Meridian and Latitudes 6°20´02´´-6o41´25´´ north of the Equator, and Longitudes 10o23´03´´ and 11o55´48´´ east of the Greenwich Meridian. It constitutes the area covered by the Nkambe Central (which doubles as the Divisional headquarters for Donga-Mantung) and Ndu Sub-Divisions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Location of the Mbum Plateau. Source: Adapted from the Shuffle Topography Mission.

Nkambe Plateau shares common borders to the West with the Misaje Sub-Division, to the North Ako Sub-Division, to the North- East Nwa Sub-Division, and the South, South-East/South-West Bui Division. The principal tribal group in the Nkambe Plateau is the Mbum, whose ancestors are believed to have hailed from Tikari in Adamawa, Cameroon. Their local dialect is Limbum. Nkambe Plateau is made up of 41 communities, with a population of 120,781 inhabitants covering a total surface area of 2112.4 km2 (CVUC, 2024), and has a population density of 57.2 persons/ km2. Most inhabitants in the Nkambe Plateau are peasants with land as the lone source of livelihood.

The Mbum Plateau have two distinctive ecological subzones and consequently two climatic features. It has a real tropical climate of Sudan Cameroon type, which has given rise to a cloud type of forest cover. The plateau is colder than the surrounding plains. The rainy season is eight months, longer than the dry season (four months) and runs from mid-March to mid-November. The maximum rainfall is in July, August and September, with an annual maximum attaining 2,332.8mm, and a minimum of 1,685.8mm (Cameroon Tea Estate-CTE, Ndu Plantation Weather Station, 2015). Unlike previously when rainfall begins in mid-March, the trends from 1995 up to date have shown that rainfall progressively starts close to the first half of January. The extent of the dry season varies because of the existence of the North East Trade Winds. The extent of the rainy season varies by the existence of the South West Monsoon, which carries moist air from the Atlantic Ocean into the hinterland. The rainy season generally begins in mid-March and ends in mid- November with rainfall amounts varying between 1,300mm to 1,900mm per annum. The mean annual range of temperature in Ndu hardly exceeds 5oC. Annually, rainfall ranges from 1,300 mm to 3,000 mm and a mean of 2,000 mm. Ndu has the Cameroonian type of climate characterized by topographically induced rainfall. In the dry season, the Mbum Plateau experiences cold mornings and hot afternoons while the rainy seasons are generally warm. The relative humidity in the dry season is less than 40% while in the rainy season, relative humidity ranges from 80-95% especially from June to September. Livestock rearing is done on the hills where there is abundant pasture in the wet season and intermittent streams and springs flow. During the dry season, most of the pasture dries up while intermittent and ephemeral streams disappear forcing livestock farmers to move down valleys where some crops are trampled upon by cattle causing farmer-grazier conflicts. Mbum Plateau has four vegetation types; grassland, savanna with trees and shrubs, forest and wooded savanna. The dominant grass species hyparrhenia and sporobus that is good for grazing. There is a reduction in grass as one moves from valleys to slopes and hills. The grassland of Mbakop, Ntamru, Mbangong, Maka, Mayo Binka and Binshu could be considered plagioclimax. In the 19th Century or so, cattle rearing was concentrated on hill slopes for fear of pasture scarcity and tsetse fly downslopes. Of recent, owing to the depletion of grazing land many cattle graze on the valleys creating farmer-grazier conflicts.

Research Design

An explanatory research design was used where it specifies the nature and direction of the relationships between the studied variables. It also uses probability sampling since the researchers generalized the results from the sample to the entire population. The pre-designed EpiData Version 3.1 database, which has an in-built consistency and validation checks, helped in minimizing entry errors during data entry. Exploratory statistics continued with further consistency, data range and validation check in SPSS VERSION 21.0 whereby outliers were sorted out using Box plots and invalid codes using frequency analysis. Boxplot is efficient in sorting out outliers because it demarcates them on a graph and at the same time indicates their exact position in the database such that they can easily be traced and verified. This approach to exploring data was particularly important for the variable dealing with household size, which was a scale (continuous variable). The verification of questionable entries was equally facilitated by the fact that all copies of the data collection instrument were given codes which codes were also entered into the database and could help refer the instrument for eventual crosschecking. The sample flow chart consists of explaining the variation in the sample from the expected sample size to the sample validated for analysis after exploratory statistics.

Research Strategy

The study used mixed methods qualitative and quantitative approaches. The use of the mixed methods approach helped to offset the weaknesses of either the quantitative or qualitative research. The study also adopted the survey research strategy to collect data on spatial challenges and planning implications in the Mbororo communities of the Mbum Plateau. The principal research instruments used for this survey were questionnaires and interviews, in which each of the respondents answered the same set of questions. A case study research strategy was used to generate a comprehensive understanding of a complicated matter of interest in the natural context. The survey research strategy was used to collect information on challenges and planning options. Through the simple random and snowball sampling techniques, 200 questionnaires were administered to the different household heads. Structured interview guides were administered through the stratified techniques. Primary data sources for the study were equally obtained through observations. Secondary data for the study were obtained through the review of published and unpublished articles, offline and online libraries, magazines, and databases and the reviewing of daily records of some private health centres.

Data Analysis

Data collected during the field survey were analyzed through two statistical techniques. The qualitative data obtained was analyzed through content analysis whereas themes and codes were given to the different opinions and perceptions of the informants and their frequencies and percentages were determined from there. Qualitative information that could not be analyzed was used as recommendation measures in the study. Inferential statistical techniques were equally used during the analysis. Here, mean and variance were mostly used. The results of the analysis were visualized on graphs and tables. The limitations of the study were that, since Mbum Plateau is prone to the ongoing political crisis, it was very difficult for the researchers to survey the entire area. In this case, Ardos, the various sub-chiefs were chosen. The independent variable for this study is climate. The elements of climate considered are rainfall and temperature. Each variable was analyzed in detail for its contribution to climate variability. Mean annual, inter-annual, measures of standard deviations, and specifically, Coefficient of Variation (CV) for rainfall reliability are analyzed systematically. Decadal variations of all climatic elements for this study and specifically, percentage changes in rainfall and temperature. All decadal variations were treated as anomalies to establish trends, illustrated in graphs (time series analysis), fitted with R2 and linear equations (coefficient of determination to show the percentage change of each climatic element). Both qualitative and quantitative techniques were, thus, employed in data analysis. Several climatic elements (rainfall, temperature) influence the climate of the Mbum Plateau. The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) is used as the main indicator of climate variability. The SPI tool was developed primarily for defining and monitoring drought (Table 1).

Table 1: Drought probability of recurrence.

|

SPI Value |

Category |

Probability (%) |

Freq. in 100 years |

Severity of event |

|

> 2.00 |

Extreme wet |

2.3 |

100 |

1 in 1 year |

|

1.5 to 1.99 |

Severely wet |

4.4 |

70 |

1 in 1.1 years |

|

1.00 to 1.49 |

Moderately wet |

9.2 |

50 |

1 in 1.3 years |

|

0 to 0.99 |

Mildly Wet |

34.1 |

45 |

1 in 1.5 years |

|

-0.1 to -0.99 |

Mild dryness |

34.1 |

33 |

1 in 3 years |

|

-1.00 to -1.49 |

Moderate dryness |

9.2 |

10 |

1 in 10 years |

|

-1.50 to -1.99 |

Severe dryness |

4.4 |

5 |

1 in 20 years |

|

< -2 |

Extreme dryness |

2.3 |

2.5 |

1 in 50 years |

Source: World Meteorological Organization (2012).

It allows an analyst to determine the rarity of a drought at a given time scale (temporal resolution) of interest for any rainfall station with historical data. It can also be used to determine periods of anomalously wet events. Conceptually, SPI is the number of standard deviations by which the precipitation values recorded for a location would differ from the mean over certain periods. In statistical terms, the SPI is equivalent to the Z-score.

Z - score = x - m........................................ (McKee et al., 1993)

Where: Z-score expresses the x score’s distance from the mean (µ) in standard deviation (δ) units.

SPI was also employed to assess the vulnerability of the livestock system to climate variation. Consistency and relationships between these climatic elements were analyzed systematically. All inter-annual and seasonal variations were treated as anomalies to establish trends, illustrated in graphs, fitted with R2 and linear equations to show variations in each climatic element. From these analyses, tables were generated to summarize climatic characteristics. The drought vulnerability for this study is assessed by reconstructing historical occurrence on an 8-month time scale, beginning in March (onset of first rains) and ending in October (end of wet season). This time scale is the wet season, where water is relatively more available and cattle production venture is rained. Detailed scenarios were presented, where the frequency of droughts was assessed annually. Typical dry season months (November, December, January, and February) were not used in assessing SPI for this study because these are normal drought season months. This drought season is one where cattle and water resources, as well as other components of the natural and human environments, are most vulnerable to weather conditions due to water scarcity. Anomalies were calculated for all climatic elements analyzed for this study.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Temperature Fluctuations

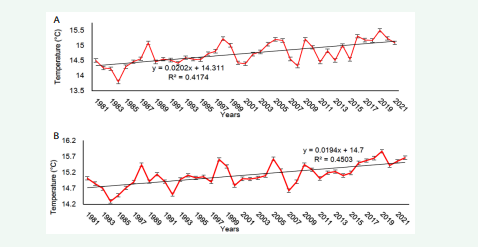

Temperature and rainfall of the Mbum Plateau have been fluctuating seasonal, monthly, and annually. The fluctuation has affected human life negatively as well as crops and animals grown on the plateau. The nature of dwindling vegetation and streams on the plateau has some links to this climatic variability and change. Minimum temperatures have been increasing and range from 14.5-15.5oC (Figure 2a,2b).

Figure 2 A: Trend in minimum temperatures of Nkambe. B: Trend in minimum temperatures of Ndu

These results show minimum temperature fluctuation in Nkambe and Ndu from 1990 to 2022 and from 1981 to 2022 respectively. The minimum temperature trend in the plateau is increasing as noticed in frequent agro-hydrological droughts affecting crops and livestock negatively. This has also affected animal and human health. Mean temperature anomalies are peculiar in 1983, 1997/1998 and 2013. The 1983 events were because of the drought that prevailed all over West Africa, while the abnormally high temperatures of 1997/1998 were caused by El Nino. The 2013 episode was caused by drought. The mean annual temperature has been increasing in Ndu (Figure 3a,3b).

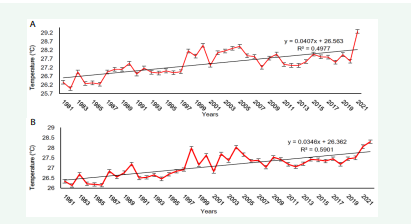

Figure 3 A: Trend in maximum temperatures of Nkambe. B: Trend in maximum temperatures of Ndu.

The maximum annual temperature trend for Ndu and Nkambe has been increasing, with a slightly increasing trend. The anomaly was noticed in 2005 as a result of the prolonged dry season that was characterized by soaring temperatures (Figure 4a,4b). The increase is more for Nkambe than Ndu as observed from the linear line.

Figure 4 A: Trend in maximum temperatures of Nkambe. B: Trend in maximum temperatures of Ndu.

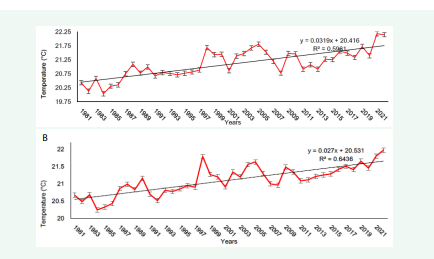

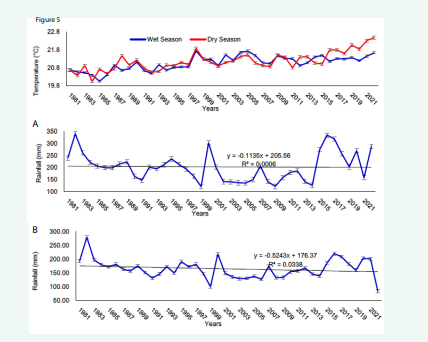

Results revealed that the mean monthly temperature trends of Nkambe and Ndu fluctuated at an increasing rate as noticed from the linear line. The abnormal temperature has a zigzag shape meaning recently it increases from January to March falls to July month and there off in December. The temperature affects cattle production through heat stress and the occurrence of diseases. High temperature leads to humidity that affects animal health. The lowest mean is observed in April and May and the highest in January, February and December. In the same vein, seasonal temperatures have been fluctuating with the same effects on cattle production and human health (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Seasonal Temperature Pattern (1981-2022). A: Annual rainfall trend of Ndu (1981-2021). B: Annual rainfall trend of Nkambe (1981-2021).

Seasonal temperature trends (wet and dry) of Mbum fluctuate at an increasing rate for the wet season and at a decreasing rate dry season as noticed from the linear line. The abnormal temperature recently is increasing from January to March and falls to July month and there off in December. The abnormal temperature affects livestock production through heat stress and the occurrence of diseases. High temperature leads to humidity that affects animal health. The lowest mean is observed in April and May and the highest in January, February and December.

Rainfall Trends in Mbum Plateau

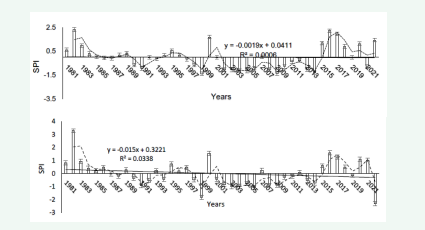

The rainfall trend in the Mbum Plateau reveals variations like in other locations across the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon and the tropics. The inter-annual variation for Ndu and Nkambe depicts a slight decrease (Figure 5a,5b). Similarly, the inter-annual pattern of the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) reveals the same pattern as inter-annual rainfall (Figure 6a,6b).

Figure 6 A: Inter-annual SPI trend for Ndu (1981-2021). B: Inter-annual SPI trend for Nkambe (1981-2021)

SPI is a critical indicator of changing climatic conditions, especially extreme weather conditions (Table 2). Persistent dry SPI episodes show that rainfall is declining, given that tropical livelihood activities are mostly rained.

Table 2: Summary of SPI episodes in the Mbum Plateau.

Table 2: Summary of SPI episodes in the Mbum Plateau.

|

SPI Value |

SPI Class |

Years |

No of episodes |

% |

|

Ndu |

||||

|

> 2.00 |

Extreme wet |

1982, 2016 |

2 |

4.76 |

|

1.5 to 1.99 |

Severely wet |

2000 |

1 |

2.38 |

|

1.00 to 1.49 |

Moderately wet |

2015, 2017, 2020, 2022 |

4 |

9.52 |

|

0 to 0.99 |

Mildly wet |

1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1988, 1989, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2007, 2018 |

11 |

26.19 |

|

-0.1 to -0.99 |

Mild dryness |

1986, 1987, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2019, 2021 |

16 |

38.10 |

|

-1.00 to -1.49 |

Moderate dryness |

1999, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2013, 2014 |

8 |

19.05 |

|

Total |

|

42 |

100 |

|

|

Nkambe |

||||

|

> 2.00 |

Extreme wet |

1982 |

1 |

2.38 |

|

1.5 to 1.99 |

Severely wet |

2000 |

1 |

2.38 |

|

1.00 to 1.49 |

Moderately wet |

2003, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2021 |

5 |

11.90 |

|

0 to 0.99 |

Mildly wet |

1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1989, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2007, 2012, 2015, 2018 |

14 |

33.33 |

|

-0.1 to -0.99 |

Mild dryness |

1987, 1988, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1994, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2019 |

18 |

42.86 |

|

-1.00 to -1.49 |

Moderate dryness |

1999, 2006 |

2 |

4.76 |

|

< -2 |

Extreme dryness |

2022 |

1 |

2.38 |

|

Total |

|

42 |

100 |

|

Extreme wet conditions were prevalent in Ndu in 1982 and 2016, as well as in 1982 in Nkambe. At the same time, severely wet conditions occurred at both locations in 2000. In Ndu, moderately wet rainfall episodes were recorded in 2015, 2017, 2020, and 2022 in Ndu, and in 2003, 2016, 2017, 2020, and 2021 in Nkambe. Moderately wet rainfall events were recorded in 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1988, 1989, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2007, 2018 in Ndu and 2003, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2021 in Nkambe. Mildly wet incidents in Ndu occurred in 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1988, 1989, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2007, 2018, and in 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1989, 1993, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2007, 2012, 2015, and 2018 in Nkambe.

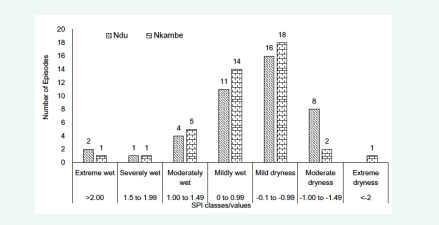

Looking at dry episodes, the distribution is as follows: mild dryness (Ndu: 1986, 1987, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1993, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2019, 2021; Nkambe: 1987, 1988, 1990, 1991, 1992, 1994, 1998, 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2019); moderate dryness (Ndu: 1999, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2013, 2014; Nkambe:1999, 2006) and the only episode of extreme dryness was recorded in Nkambe in 2022. These results revealed that seven of the eight SPI classes have been recorded in the Mbum Plateau (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Summary of SPI episodes for Ndu and Nkambe.

Between 1981 and 2022, the various SPI episodes were as follows: extreme wet (3) (Ndu: 2, Nkambe: 1); severely wet (2) (Ndu: 1, Nkambe: 1); moderately wet (9) (Ndu: 4, Nkambe: 5); mildly wet (25) (Ndu: 11, Nkambe: 14); mild dryness (34) (Nsu16: Nkambe: 18); moderate dryness (10) (Ndu: 8; Nkambe: 2) and the only extreme dryness (1). These results show that rainfall in the Mbum Plateau is declining, with 24 dry episodes in Ndu (57.14%) and 21 (50%) in Nkambe. This gives a total of 45 dry episodes (53.57%) in the entire plateau.

A closer look at the decadal climatic analysis in the Mbum Plateau, rainfall and temperatures have been oscillating remarkably, with a tendency of rising temperatures and declining rainfall (Table 3).

Table 3: Summary of rainfall and temperature characteristics of the Mbum Plateau.

|

Decades |

Mean RF (mm) |

Mean Temp (?C) |

RF SD |

RF CV (%) |

Mean SPI |

SPI class |

RF Reliability |

RF Trend |

Temp. Trend |

|

Ndu |

|||||||||

|

1981-1990 |

227.02 |

20.68 |

47.75 |

21.03 |

0.4 |

Mildly wet |

Unreliable |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

1991-2000 |

198.76 |

20.98 |

50.23 |

25.27 |

-0.07 |

Mild dryness |

Unreliable |

Increase |

Increase |

|

2001-2011 |

155.77 |

21.26 |

27.94 |

17.94 |

-0.8 |

Mild dryness |

Reliable |

Decrease |

Stable |

|

2012-2022 |

233.71 |

21.47 |

72.91 |

31.33 |

0.5 |

Mildly wet |

Unreliable |

Increase |

Increase |

|

Average |

203.82 |

21.10 |

49.71 |

23.89 |

0.01 |

Mildly wet |

Unreliable |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Nkambe |

|||||||||

|

1981-1990 |

185.4 |

20.54 |

36.23 |

19.54 |

0.59 |

Mildly wet |

Reliable |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

1991-2000 |

161.45 |

21.00 |

33.24 |

20.59 |

-0.11 |

Mild dryness |

Unreliable |

Increase |

Increase |

|

2001-2011 |

141.18 |

21.32 |

14.81 |

10.42 |

-0.66 |

Mild dryness |

Reliable |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

2012-2022 |

172.85 |

21.49 |

39.44 |

22.82 |

0.22 |

Mildly wet |

Unreliable |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Average |

165.22 |

21.09 |

30.93 |

18.34 |

0.01 |

Mildly wet |

Unreliable |

Decrease |

Increase |

RF SD: Rainfall Standard Deviation; RF CV: Rainfall Coefficient of Variation; SPI: Standardized Precipitation Index.

From 1981-2022, the climatic characteristics were as follows: 1980-1990 (Ndu: mean rainfall-227.02 mm, mean temperature-20.68oC, CV-21.02% (unreliable), with a mean SPI of 0.4 (mildly wet), giving a decreasing rainfall and an increasing temperature trend; Nkambe: mean rainfall-185.4 mm, mean temperature 20.54oC, CV-19.59% (reliable), mean SPI of 0.59 (mildly wet), resulting to a decreasing rainfall trend and rising temperatures. During the 1991-2000 decade, the characteristics were: (Ndu: mean rainfall-198.76 mm, mean temperature 20.98oC, CV-25.27% (unreliable), giving rise to an increasing rainfall trend and increasing temperature; Nkambe: mean rainfall-161.45 mm, mean temperature-10oC, CV-20.59% (unreliable), resulting to increasing rainfall and temperature during this decade. Rainfall and temperature characteristics during the 2001-2011 period were as follows: (Ndu: mean rainfall-155.77 mm, mean temperature-21.26oC, CV-17.94% (reliable), giving a decreasing rainfall trend and a stable temperature; Nkambe: mean rainfall-141.18 mm mean temperature-21.32oC, CV-10.42% (reliable), with an increasing rainfall trend and a decreasing temperature trend. The last decade (2012-2022) had the following characteristics: (Ndu: mean rainfall 233.71 mm, mean temperature-21.47oC, CV- 31.33% (unreliable), with an increasing rainfall and temperature trends; Nkambe: mean rainfall-172.85mm, mean temperature- 21.49oC, CV-22.82% (unreliable), with a decreasing rainfall and increasing temperature trend.

These oscillating temperature and rainfall trends are a climate challenge to the indigenous Mbororo communities of the Mbum Plateau as their livelihood activities are rained [5,7,14]. Noted that the pastoral community in the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon faces a range of challenges related to climate and the environment, particularly in the highland rangeland ecology. These challenges compound existing issues such as insecure pastoral tenure, land grabbing, degradation, poor land use planning, and dwindling rangeland resources. Indigenous knowledge has identified several related effects, including pasture scarcity; weed invasion, poor range products, cattle mortality, degradation, land use conflicts, and dwindling water resources. In response, pastoral communities have been working with development agencies to develop greater resilience in the face of these challenges, including measures such as cultivating improved pastures and fodder crops, developing water schemes, and adjusting the grazing calendar. However, there is a need for the transfer of technical and financial resources to mitigate risks and build capacities, ultimately reducing the vulnerability of pastoral communities for a sustainable future.

Dwindling Vegetation and Cattle Production

According to the Divisional Delegate of MINEPIA Donga- Mantung, about 65% of the Mbum Plateau rangeland has been destroyed by bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) which affects cattle production reducing grazing size. This plant is allopathic and has substances excreted from the plant and leached into the soil. Bracken fern causes a medical problem known as enzootic hematuria in animals. This results in the appearance of blood in the urine of cattle. Fresh bracken ferns are more toxic than dry ones. Since it grows well in the wet season, it is often very tempting to cattle which in most cases are eaten by cattle as pasture. Today, the percentage areal coverage of vegetation types in the Mbum Plateau is as follows: asporobolo africanas 35%, Pennisetu clandestine 15%, Hyparrhenia spp 15%, bracken fern 20% and weed 15%. The relatively high percentage area coverage of bracken fern is because it can multiply fast and occupy vast expanses of land. In the course of its growth, it shades the underground palatable vegetation from sunlight, reducing metabolic activities and denying cattle the right to feed on pasture. The different activities now carried out on rangeland have made it greatly dwindle over the years. Satellite images revealed that in 1980, tea occupied 14.74%, settlement 5.29%, and farm and grazing land 79.69%. In 2022, tea covers 0.47%, settlement 7.51%, and farm and grassland 82.55%.

Water Scarcity and its Effects on Pastoral Activities

Water scarcity impedes pastoral activities. Field survey revealed that only very few Mbororo have access to pipe-borne water in the Mbum Plateau. The majority travel over half a kilometer to access water that is untreated and served for drinking as most are from the source with cattle. Because cattle greatly consume water more than humans do, the demand for it among the Mbororo exceeds that of the local Wimbum People. Field observation revealed that some 20-30 years ago, water was about three times more than that existing today in the Mbum Plateau. The planting of Eucalyptus especially of water has greatly caused water points to dwindle. Reduced trends of evapotranspiration have also helped in reducing stream discharge. The herders today depend on very few water points for their cattle and in the dry season, situations are often worse. The deplorable conditions cause animals to lose weight and are easily attacked by diseases. In the dry season, there is high turbidity in springs and streams especially in Ntumbaw, Binka, Binshu, Nkwitang, Kungi and Mbarseh as animals drink and mess on the water body. This situation increases ingested germs and diseases like rider pests, tuberculosis, hemorrhagic septicemias, and diarrhoea prevalence among animals. An increase in areal coverage by eucalyptus has negatively affected water discharge and availability. These findings are consistent with that of [1,3,9] showing that the human pressure on the water source is negatively impacting on water supply on the Plateau. Field observation that trees increase rainfall (65%), moderate temperature and increase atmospheric humidity (86%), increase stream discharge (76%) and content soil from erosion (65%). It should be understood that eucalyptus consumes at least 30 liters of water a day, thus replacing natural vegetation with this species like in Mbum Plateau has caused server water crises in some neighbourhoods (Table 4).

Table 4: Annual water supply in natural forested and eucalyptus catchments of the Mbum Plateau.

|

Catchment area |

1980 |

2024 |

Ecological status |

Estimated annual water yield (m3) |

Nature of water flow |

|

Njap |

1 |

1 |

Forested |

148.6 |

Gravity flow |

|

Binshu |

1 |

0 |

100% deforested |

247.9 |

Pumped |

|

Binka |

1 |

1 |

Forested |

189.7 |

Gravity flow |

|

Mbot |

1 |

0 |

100% forested |

66.8 |

Irregular |

|

Bikop |

1 |

0 |

100% forested |

83.3 |

Irregular |

|

Wat |

1 |

1 |

100% forested |

87.7 |

Gravity flow |

|

Mbaa |

1 |

1 |

100% forested |

299.9 |

Gravity flow |

|

Chup |

1 |

1 |

100% forested |

29.2 |

Gravity flow |

|

Boyon |

1 |

0 |

100% forested |

89.3 |

Gravity flow |

|

Mayo-Binka |

1 |

1 |

100% forested |

103 |

Gravity flow |

|

Mbukop-Taku |

1 |

1 |

100% forested |

23.1 |

Seasonal |

|

Ntundip |

1 |

1 |

100% forested |

99.9 |

Irregular |

|

Njitop |

3 |

0 |

100% forested |

167 |

Gravity flow |

|

Ndu |

1 |

0 |

100% forested |

199.8 |

Irregular |

|

Wowo |

1 |

1 |

Forested |

97.2 |

Seasonal |

|

Mbarseh |

4 |

1 |

100% forested |

82.1 |

Gravity flow |

|

Mbawgong |

3 |

1 |

100% forested |

53.6 |

Seasonal |

|

Nkwitang |

3 |

1 |

100% forested |

67.3 |

Gravity flow |

|

Mangu |

5 |

2 |

Planted eucalyptus |

56.5 |

Gravity flow |

|

Kaka |

3 |

0 |

100% forested |

20.1 |

Irregular |

|

Ntumbaw |

2 |

0 |

100% forested |

19.2 |

Irregular |

|

Mbafung |

1 |

0 |

100% forested |

301 |

Regular |

|

Tukop |

2 |

0 |

100% forested |

22.2 |

Irregular |

|

Njipku |

2 |

2 |

Planted eucalyptus |

23 |

Seasonal |

|

Lus |

5 |

0 |

100% forested |

23 |

Seasonal |

|

Nkambe |

3 |

0 |

100% forested |

25 |

Irregular |

Source: complemented by fieldwork (2024).

The initial pasture cover of the area some years ago was Guinea and Sudan Savanna and recently it has mostly been colonized by bracken fern. This is a clear indication that the climate is changing and this has contributed to significant changes in the pastureland. Years with high rainfall as is the case between 1980 to 1999 in Ndu, nutritive pasture for cattle was highly favorable. But with the decreasing trends of rainfall since 2000, bracken fern is pre- dominating the area. As climatic elements changed over time, the initial ecological equilibrium conditions, which were formerly favoring the growth and multiplication of cattle pasture, changed equally over the years. This finding corroborates that of [2,11] studying the effect of the montane forest of Ndu and the water crisis in Nkambe Highland respectively. Agriculture activity has a great impact on land use changes (45%), planting of eucalyptus 26% and cattle grazing 20%. This finding is similar to that of [3 ,9,11] who all indicated environmental destruction especially eucalyptus planning in the Nkambe plateau has an increased water crisis. Today, market gardeners have exposed more wetlands for more evapotranspiration. This is very common in villages of Mangu, Njipnkang, and Ngarum that cultivate huckleberry in the dry season.

Animal pasture within certain areas of the Mbum Plateau has changed from its initial form and wild shrubs now colonize it. This finding is proven by the fact that, out of the 200 cattle graziers who were randomly selected, over 64% of herders believed that pasture availability for cattle has reduced in supply lately. This is opposed to 36% of the herders who hold that pasture available for cattle is significant and unlimited and therefore can effectively sustain the carrying capacity of grazing animals. As rainfall decreases, the quality of pasture is negatively affected as this was observed by graziers in 2010/2011, 20017/2018, 2019, and 2020. Formerly, the Mbororo women were highly involved in the selling of milk but today milk production has greatly reduced from about 5litters per cattle in the 1970s to 1190s and today ranging between 1.5 to 2litters per cattle. From 80 households sampled on the field, an average of 4-6 children were schooled some 20- 30 years ago per community but today, each Mbororo family has about 4-5 children in school. The main source of capital to fund the family comes from cattle farms thus, a reduction in cattle. With this situation, some Ardos like Bakari of Ntisaw started leasing grazing land to the local Wimbum People mounting tension with the local chiefs. Ardo Mbuye of Mbawngong had to surrender his power to his son Bonjaye in 2011 simply because he had no cattle, which is the right to power. The leasing of grazing land in Mangu, Mbawngong, Binka, Nkwitang, and Ntisaw by some Mbororo is mounting tension between them and the local Wimbum. Because of trying to resolve the mounting tension, Fon Nformi (Fon of Ndu) started distributing part of grazing land in Nkwitang, Ntisaw, and Mbawngong, which has fueled the difference between Mbororo and Wimbum communities.

The impacts of climate variability in the cattle production sector of the Mbum Plateau include the decrease in production, emerging food insecurity, floods, the prevalence of pests and diseases, rising temperatures, dry spells after the first rains, soil erosion and leaching, the drying up of water bodies, the reduction in the volume of streams and farmer-grazier conflicts. The impact of climate vulnerability has been expressed in the recurrent dry spells after the first rains, with a perception score of 63.2%, while 3.7% the no perception and 21.1% did not know perception. Farmer-grazier conflicts too have been impacted by climate vulnerability with a perception of 63.4%, 28.4% of no perception and 8.2 % do not know perception. The drying up of streams and springs had the lowest perception of 44.4% with 20.1% no perception and 35.5% not knowing perception. This then gives a deeper meaning to understanding the impact of climate variability in the Mbum Plateau. Looking therefore at the trends concerning impacts of climate variability, dry spells, reduction in water, and farmer-grazier conflicts had the highest perceptions as compared to the drying up of streams, rising temperature, food insecurity, and floods.

The poor and dilapidated structures in the cattle-breeding sector significantly contribute to a drop in cattle numbers as revealed by 55% of Mbororo interviewed on the field. Farmer graziers conflicts are the continuous struggle for the use of the same piece of land between two sets of people: graziers and crop cultivators and among graziers themselves. In this situation, they are always trespassing by one of the groups in each other’s preferred zone of activities. These conflicts are rampant in Mbum Plateau as most graziers are today leaving for transhumance before the stipulated time when most second cycled crops (cocoyam, beans, cassava and sweet yams) are only completely removed from the farms by the 30th of December. We equally observed that farmer-glazier conflicts are not confined to transhumance zones in the Mbum Plateau but have been extended to their night paddock zones in the highlands where 76% of the graziers do not have fences for their cattle to sleep. As such, during the night periods, many cattle stray into crop farms destroying crops.

The farmer-grazier conflicts are very common in Binka, Mbawngong, Ntiso, Mangu, and Ntumbaw. Transhumance rapidly spreads contagious diseases and endangers cattle. An early departure on transhumance sometimes means that the animals miss out on the vaccination. These herds endanger others that are vaccinated. The cattle moved into areas infested with ticks, tsetse flies associated with trypanosomiasis and swamps infested with arthropod vectors of arboviruses. The most common diseases in transhumance areas of Mbaw and Dumbo include foot and mouth, bovine pleuropneumonia, trypanosomiasis, Anthrax and blackleg, and Black quarter. Herders on their side are attacked by brucellosis and tuberculosis. The recurrent conflicts have resulted in some Mbororo herders migrating permanently out of the region to Foumban, Sabongari, Tibati, Foumbot, and Nigeria. Currently, it has been observed that the time for cattle herders to move with their herds to the lowlands has not changed significantly. Instead, the return movement to the highlands has changed over time. This is so because the late onsets of rains delay pasture rejuvenation in highland areas thus forcing graziers to stay longer in the lowlands unlike before. Formally, the month of March usually marked the movement of cattle to the highlands. Nowadays, this movement has shifted more to May (due to the shifting patterns of rainfall, which is the main source of input to pasture). The prolonged stay in the lowlands has resulted in farmers-graziers conflict as both calendars of activities of farmers and grazers coincide with each other. This goes to justify what [15] mentioned earlier. This is so because as of May, most of the crops have grown to a certain level of maturity. As such, their freshness attracts cattle because grass that was formally grazed on is no longer available to sustain their numbers.

The most common disease in the area is foot and mouth disease locally called “Pial and Mborow” respectively. Cattle affected by these diseases are seen lying on the ground for long hours. This is due to their inability to trek or stand for long and graze on the natural pasture. Babesiosis, a disease that emerged a few years back, could be linked to Climate variability. It causes animals to urinate blood. Its spread is so rapid that over 40% of cattle have contracted it. This disease is said to have emerged due to the late onset of rains in the Mbum Plateau. Another climate variable-related disease is ectoparasite (ticks), flies and flees. The prevalence rate of climate-related diseases is higher among the Mbororo breed that graze on common pastureland (Table 5).

Table 5: Seasonal patterns of cattle diseases and vaccines.

|

Wet season |

Vaccine |

Dry season |

Vaccine |

|

Endo parasite effect caused by ringworm & tapeworm |

Levamizole & ivomectin |

Rinderpest |

Bovipestova |

|

Ecto-parasite effects caused by heavy tick infestation & ringworm |

Cypermethrin spray |

Trypasonomiasis |

Trypanocide or trypanmedium |

|

Foot & mouth disease |

Vaccine not available |

Tuberculosis |

Locally treated |

|

Mastitis & babesisiasis (tick fever) |

|

Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia |

Pastoral |

|

Lumpy skin disease |

Nodolovax |

Haemorrahagicsepticaemia |

Nodolovax |

|

|

|

Black quarter |

Pelyvax |

Source: Divisional Delegation for Livestock, Fisheries & Animal Husbandry, Donga-Mantung Division 2023.

Mbororo has a holistic view of cattle and they search for the cause of a disease both naturally and the sick cow are monitored through taste, reaction to touch, and smells. In this process, supernatural methods such as consultation of gods are also made use. This has not been very conducive to the constant climatic variability noticed on the Mbum Plateau.

The Changing Social and Economic Structure of the Mbororo Community

Since the entry of the Mbororo into the Mbum Plateau, their lifestyles have been changing. They have moved from temporal housing structures to permanent houses, from nomads to sedentary and crop farmers.

The Traditional Lifestyle and Labour Distribution of the Mbororo

The traditional lifestyle of the Mbororo is unique and interesting, for their daily and seasonal movement is determined by their animal needs such as food, water, air, and animal protection. Most of these needs were available at various times and in different places in quantities adequate to ensure the survival of the herds and of the households that depended on them. Mbororo man and his wife had very few possessions and maintained a small family. This made it very easy for them to move from place to place and whenever they settled, round huts were constructed with a few sticks and straw which is readily available in the savanna. They look down on agriculture and prefer to buy whatever they need from the local Wimbum people. The Mbororo who were recognized by the UN in 2004 as indigenous people in Cameroon claimed their origin in the country although they had no permanent settlement to sustain their herding activities. Men’s responsibilities are numerous as the management of the herd falls on them. But children in their capacity as apprentices also contributed to the labour force. Men ensured the corporate existence of the family and provided for the house. They protected the animals from carnivores and raiding tribes. They cater for the animals to distance pasture lands, make weapons like guns, knives, swords, herding sticks, bows and arrows, find grazing sites, build camps and fences, and perform soil and water tests. Girls and women wove mats, spun cotton into thread, made household decorations, and collected herbs and vegetation. They buy food from the market, milk the cows, churn the milk, make the butter, sell milk and butter, and do craft work such as decorating calabashes. The women and girls also grow vegetables and raise poultry and non-ruminant stock. They cleaned the compound, looked after the disabled animals, fetched water, collected firewood, collected wild food, helped in making temporary shelters, and bore and nurtured the children. Sometimes the women prepared dakere (a mixture of corn fufu, milk and sugar) for sale. They also fried some chewable like makara, maser and pancakes for sale. This lifestyle has changed as most of them no longer have cattle and resorted to different occupations, leasing and selling rangeland, and schooling besides the creation of water points. Mbororo Ardos who are without cattle today such as Bakari of Ntisaw, Mbuye of Mbawngong and other notables have even left the plateau elsewhere.

With the changing lifestyles of the Mbororo, transhumance has been intensified. Coupled with the changing climate, the scarcity of drinking water up slopes of Wat, Binshu, Binka, Nkambe, Mbawngong, Ntisaw, Nkwintang, Mangu and Ntubaw besides reducing the quality and quantity of pasture has increased more pressure on Mbororo communities. In the course of transhumance cattle up slopes descent to Mbaw Plain, Misaje, and Dumbo. This process has inherent problems. Mbororo often loses stocks due to the prevalence of animal diseases accompanied by poor access to veterinary attention and their high dependence on ethno-veterinary medicine with doubtful outcomes. Foot-to- mouth diseases, black quarter, lice, and ticks are very common on transhumance tracks. Transhumance is another source of tension between the Wimbum and the Mbororo communities. In the course of this process, cattle pass through farms destroying crops and initiating farmer-grazier conflicts. Some cattle fall in cliffs and large gullies. The environmental causes of farmer- grazier conflicts vary from rugged relief (20%), soil exhaustion and scarcity of land due to the absence of boundaries between grazing and crop farming lands (40%), leasing of pastoral land 10% and settlement on rangeland 10%. Since land is often small for graziers and crop farmers, there is bound to be clashes with both parties accusing each other of encroaching on the land meant for them. The introduction of hollow frontiers to the farmers and graziers has instead increased conflict between them in Dumbo, Misaje and Mbaw plain, especially in the dry season when they are scrambling for it to carry out their activities. The farmer-grazier conflicts existed but were not as pronounced as nowadays. Interviews conducted with the Mbororo communities revealed that 75% were constantly moving because they did not want to stay under the shameful situation of the area, they once role with cattle, 64% were for increasing herder-herder conflicts being on the increase, 20% were neutral and 16% said farmer- graziers conflicts were on the rise [16]. This situation is common in Mbawngong, Ntumbaw, Ntamru, Binka, Wat, and Ntisaw. At first, Ardo’s position was reserved only for the Mbororo who had the highest number of cattle in the community but nowadays, some natives have been given the position posing conflicts between Mbororo herders. Many are taking different professions while others have left the plateau for other favorable grounds.

From milking cattle, Mbororo women were engaged in dakere production (mixture of corn fufu, milk and sugar) for sale. With the reduction in cattle and grassland, the women have emancipated themselves from secluded life and now into restaurants and even farming. They now plant crops like corn, beans and cassava. This is because most of them are unable to meet the cost of food in the local markets besides the fact they do not have enough cattle to sell like before. Many men and women are moving into towns and cities to gain employment as night watchmen (28%), hawkers (30%), drivers (40% and security guards (23%). Some after receiving their salaries entered the second clothes business alongside their night watch duties; others have opened stores in Bamenda, Bafoussam, Douala, and Kumbo. Some are involved in traditional herbs businesses moving and selling traditional medicine.

In the same light, some after mismanagement of their cattle started stealing cattle and attacking businesspersons and women along major highways. This is common between Kom roads and Lus Road in the Nwa Sub-Division, and Ntumbaw and Mbaw Road in the Ndu Sub-Division. They sometimes lot passengers, collect money and other properties. The statistics from Nkambe Central Prison revealed that the number of Mbororo inmates keeps increasing from 19 in 2014 to 47 in 2023. This is more linked to the fact that their cattle have greatly dwindled. From the household interview, 80% revealed that some 20 years ago, they had either two children or one in school but today they have an average of 6-8 children in school. Statistics obtained from the Divisional Delegate of Primary Education for Dunga-Mantung Division, 789 Mbororo children are found in schools in Mbum Plateau [17-20]. The problem of water scarcity has been looked into by the Municipal Council of Nkambe in collaboration with the Mbororo Cultural and Development Association (MBOSCUDA), the Mbororo communities under Ardo Sally, Ndemsa and Usmanu where pipe-borne water has been constructed. The main problem now is maintenance as most of them lived secluded lifestyles, finding it difficult to carry out community work.

LIMITATIONS TO THE CHANGING SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC LIFESTYLE IN THE MBORORO COMMUNITIES

The Mbororo faced a lot of problems like predicting climatic variability, disease prevalence, reducing drinking water points for cattle, increase in food prices, constant encroachment of population into rangeland and modernization of their archaic culture. Out of the 200 sampled Mbororo, 80% revealed wrong climatic prediction, 8% talked of archaic lifestyles, 15% had a high cost and 45% insisted on all the problems. Although some of the Mbororo have adapted to climatic fluctuation through changes in the pastoral calendar, breeding of new hybrid cattle species, predicting drought or extreme dry season and poverty remains a great task. The problem is more because only a few weather stations exist on the plateau that do not spread climatic information to the citizens. Findings revealed that, in the past, the species of cattle reared in the Mbum Plateau were all local breeds. These breeds included the red Fulani, Gudali, and white Fulani, which are not resistant to pests and diseases and produce only one to two litres of milk a day. They equally lose a lot of weight hence low meat content during the dry season. The Houston breed imported from the USA (with white and black strips) is purposely for the fact that it produces a lot of milk. Contrary to the local breed, which produces 1-2 litres of milk a day, the Houston breed produces 5 to 17 litres daily. With the importation of this species, the problem of inadequate milk could be partially solved, but given the fact that it is very expensive and most cattle graziers cannot afford it, the problem remains. The Mbororo have not been able to adequately adapt to the present situation due to their inability to resist the current situation of low rainfall and high temperatures with a consequent reduction in pasture land. As a result of these problems, graziers in the rangelands of Mbororo communities have resorted to improved cattle breeds. The construction of animal dips which is conducive to treating the ectoparasite of cattle is expensive for the Mbororo, the new adaptation has remained in their minds as a result of hardship. Adaptation to some Mbororo remains difficult as they attribute it to the anger of the ‘gods.’ Many refused resistant hybrid from the government and cattle treatment provided by the government preferring their local ones.

CONCLUSION

Cattle breeding remains the main livelihood of many Mbororo, which supplements and enriches their diet. It provides animal waste such as manure, beef and milk. The Mbororo of the Mbum Plateau engages in this activity with virtually no economic resources due to free rangeland their native methods of treating cattle diseases. The Mbororo without cattle today on the plateau has greatly reduced as a result of climatic fluctuation, dwindling rangeland and water points as well as their changing lifestyles toward modernization which is strange within their communities. Drought has been very common in a situation where the Mbororo hardly supplement their cattle with grass or water points. This predisposes the Mbororo communities to climatic hazards that directly impact their economic and social lives. While strongly recommending that an understanding of climate and socioeconomic lifestyle changes of Mbororo should be motivated with sustainable life skills, human health and food security by improving cattle breeding should also be looked into by the Government. Pest and disease contentment measures must be properly enforced in the Mbum Plateau. Climatic data should be analyzed and information from it spread to the local communities to minimize negative impact on the communities. There is a need for the collection, processing, and dissemination of weather information that considers a more specific area rather than generalization based on the zones. This can be done by establishing automated weather stations in the Mbum Plateau. Skills development training for the poor Mbororo to prepare them for diversification, particularly during periods of low agricultural output is also important. Similarly, targeted policy interventions should be investigated to promote agro-based industries to create employment opportunities for the Mbororo communities as a way of encouragement and morale booster for herdsmen. Adequate and quality health education should be mounted in the various bush settlements to improve on health condition of the Mbororo. Campaigns on detecting environmental changes and health effects from drugs and reports should be reported to MINEPIA authorities for investigation. Through this, many unfriendly drugs may be withdrawn from the market. Grazing certificates should be issued to legal graziers and they should be adequately sensitized to demarcate grazing from farmland using bark wire, not bamboo that cattle can easily break through. More dialogue platforms should be created by the local council, which promotes the amicable settlement of farmers and graziers to minimize farmer-graziers conflicts. MINEPIA should encourage pastoral extension and sociology that can change the Mbororo behavior through education and information dissemination on the plateau. Regulations should be implemented to manage transhumance to reduce the risk of losing animals during the process. This will further reduce farmer-grazier conflicts that are frequent on the plateau. The planting of eucalyptus should be restricted and encourage planting of natural vegetation in watersheds.

REFERENCES

- Ngwani A, Balgah SN, Kimengsi JN. Urban planning challenges and prospects in Nkambe town, Northwest Region of Cameroon. Journal of Geography, Environment and Earth International. 2020; 24: 83-95.

- Nfor JT, Umaru B, Achankeng ET, Tsalefac M. Land and water resources management in Nkambe Highlands of Cameroon. Challenges and perspectives. Joint proceedings of the 27th Soil Science Society of East Africa and the 6th African Soil Science Society 20-25th October 2013; Nakuru, Kenya.

- Niba MLF, Kinyui CN, Mbu BK. Drainage basin anthropization and implication on water availability in the Mbum Plateau of Cameroon. International Journal of National Resource Ecology and Management. 2022; 7: 121-131.

- Tume SJP, Kongnso ME, Nyukighan MB, Dindze NE, Njodzeka GN. Stakeholders in Climate Change Communication in the Northwest Region of Cameroon.

- Mairomi HW, Tume SJP. Standardized Precipitation Index Valuation of Seasonal Transitions and Adaptation of Pastoralist to Climate Variability in Rangelands of the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon. Journal of Ecology and Natural Resources. 2021; 5: 1-20.

- Tume SJP. Rainfall Characteristics of the Bamenda Highlands and Coastal Lowlands of Cameroon: Examples from Ndu and Douala. 2023.

- Fogwe ZN, Kimengsi JN, Sunjo TE, Kometa SS, Nkwemoh CA. Celebrating Ten Years of Restless Rest in Landmark Research and Human Resource Development: Festschrift for Professor Emeritus Cornelius Mbifung Lambi: Development and Environmental Dynamics. The University of Bamenda Printing Press. 2023; 170-180.

- Tume SJP. Rainfall Reliability in the Bamenda Highlands and Coastal Lowlands of Cameroon: Insights from Ndu and Douala (1957-2016). Environment & Ecosystem Science (EES). 2024; 8: 26-35.

- Amawa SG, Kimengsi JN, Tata ES, Awambeng AE. The Implications of Climate Variability on Market Gardening in Santa Sub-Division, Northwest Region of Cameroon. Environment and Natural Resources Research. 2015; 5: 14-23.

- Ngwani A, Nformi R, Funwi GN, Yinkfu RN. Spatial planning challenges and implications on the development of Nkambe and Ndu secondary towns in the North West Region of Cameroon. International Journal of Current Research in Multidisciplinary (IJCRM). 2023; 8: 1-14.

- Nganjo NR, Wanie CM, Mbanga LA. The Effects of Deforestation of Tropical Montane Forest on Drinking Water Supply in Ndu Sub- Division, North West Region of Cameroon. Journal of Sustainable Resource Management. 2016; 4: 1-11.

- Tume SJP, Zetem CC, Nulah SM, Ateh EN, Mbuh BK, Nyuyfoni SR, et al. Climate Change and Food Security in the Bamenda Highlands of Cameroon. 2020; 107-124.

- Squires VR, Mahesh K, Gaur MK. Food Security and Land Use Change under Conditions of Climate Variability: A Multidimensional Perspective. Springer Cham. 2020.

- Tume SJP, Fogwe ZN. Standardised Precipitation Index Valuation of Crop Production Responses to Climate Variability on the Bui Plateau, Northwest Region of Cameroon. Journal of Arts and Humanities. 2018; 1: 21-38.

- Lambi CM. Revisiting the Environmental Trilogy: Man, Environment and Resources. 2001.

- In Lambi CM. Environmental Issues: Problems and Prospects. Unique Printers, Bamenda. 2001; 105-117.

- Addressing the challenges of urbanization in Africa. A summary of the 2019 Africa Policy Circle discussions. African Policy Circle.

- Balgah RA, Kimengsi JN, Wirbam BMJ, Forti KA. Farmers Knowledge and Perceptions to Climate Variability in Northwest Cameroon. World Journal of Social Science Research. 2016; 3: 261-273.

- World Meteorological Organization, (2012). Standardized Precipitation Index User Guide. WMO (1090), Geneva, 50.

- Tume SJP, Tanyanyiwa VI. Climate Change Perception and Changing Agents in Africa & South Asia. Vernon Press, Wilmington. 2018; 97- 116.