Moral Distress by A Thousand Cuts: A Mixed Methods Study on Nurses in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic

- 1. College of Nursing, University of Utah, East Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

- 2. Resiliency Center, University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA

Abstract

Background: Manifestations of Moral Distress (MD) in nurses encompass psychological feelings of frustration, guilt, and inner conflict. Especially following the pandemic, addressing moral distress is crucial for ethical decision-making and nurse well-being.

Methods: A sequential explanatory mixed-method research design was utilized, combining quantitative data collected via an online survey from July to August 2023 and qualitative data from interviews in September 2023. Eligibility criteria included registered nurses in Utah, aged 18 and older, with no restrictions on gender or race. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS© version 28, and qualitative data were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis. The integration of both datasets was achieved through a critical mixed-methods process to ensure a cohesive examination of experiences.

Results: A total of 191 participants completed the online survey, with an average age of 38 years, predominantly female (83.2%), and mostly identifying as White (88.9%). Nurses in acute settings did not report higher levels of MD compared to those in non-acute settings, and the overall regression model did not significantly predict MD. Team dynamics significantly moderated the relationship between resilience and MD, with higher resilience associated with lower MD in settings with lower team dynamics. Despite the significant interaction, the final regression model explained only a modest portion of the variability in MD, indicating other factors also influence MD in meaningful ways.

Discussion: Moral distress significantly influences team dynamics, leading to strained communication and decreased collaboration. Positive team dynamics can mitigate moral distress and enhance patient care. Resilience acts as a protective factor against moral distress, necessitating a supportive work environment. In this study, nurses described burnout, perceived deficiencies in nursing education, disconnect with management, and systemic challenges.

Conclusion: Moral distress is pervasive in healthcare, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses face complex challenges requiring support and enhanced education. Positive team dynamics, resilience, and coping mechanisms are vital for nurse well-being and patient care. Recognizing moral distress and fostering post-traumatic growth is integral to nurse empowerment and compassionate care delivery.

Keywords

- Moral Distress

- Burnout

- Team Dynamics

- Resilience

- Post-Traumatic Growth

Citation

Ansari N, Warner E, Swanson LT, Epps JV, Wilson R, et al. (2024) Moral Distress by A Thousand Cuts: A Mixed Methods Study on Nurses in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JSM Health Educ Prim Health Care 6(1): 1050.

BACKGROUND

Being a nurse in today’s healthcare system can be challenging, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic which turned healthcare on its head and magnified a host of issues faced by nurses and other healthcare workers. Although a nurse’s goal is to provide dignifying care and foster optimal patient outcomes, they are often forced to navigate a system that is complex and flawed. The American Nurses Association’s Code of Ethics [1] “establishes the ethical standard for the profession” and is often used by nurses as a guide to work through challenging situations in the workplace. When a nurse’s moral foundation clashes with circumstances that are not in line with ethical practices, they may experience moral distress. Moral distress is defined as negative emotions that occur when a nurse cannot carry out a moral- based decision secondary to competing interests and obstacles [2]. Moral Distress (MD) can manifest physically (e.g., heart palpitations) as well as psychologically (e.g., depression, low self- esteem, feelings of incompetence, and relationship difficulties) [3]. Sources of MD include poor staffing, interprofessional conflict, and inappropriate treatment decisions [3]. Consequences of moral distress include compassion fatigue, medical errors, and a high level of nurse turnover [3].

The emotional trauma resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has made nurses more aware of MD and its cumulative effects. Sources of MD specific to the pandemic included lack of personal protective equipment, causing increased anxiety about contracting the virus themselves and/or passing it on to family members; inability to provide the standard of care secondary to operating in crisis mode; inadequate staffing due to the overwhelming number of critically-ill patients; restrictive visitor policies; conflicts between team members secondary to lack of proficiency in caring for critical patients and arguments over treatment decisions; and feeling helpless in being unable to help patients die with dignity [4]. Providing equal care to a group of patients (i.e., engaging in the ethical principle of justice) was nearly impossible in the early stages of the pandemic, when hospitals were overrun with very sick patients and limited resources had to be allocated to certain patient groups [4]. Healthcare professionals were exposed to a great deal of MD during the pandemic, and with the potential for future pandemics, it is crucial to support healthcare workers when they face morally distressing situations; otherwise, there is a risk of accumulating MD which eventually will drive nurses away from the bedside profession.

The concept of MD has come under greater scrutiny since the pandemic, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding and potential interventions and remedies. Previous research has examined contributing factors, such as the effects of resilience and coping strategies on levels of MD, and the relationship between MD and team dynamics [4]. However, there remains a significant gap in understanding how these factors interact across different experience levels and patient care settings in the nursing field. The current study aims to fill this gap by providing a comprehensive examination of MD through the analysis of moderating factors, including years of nursing experience, patient care setting, resiliency, and team dynamics. Specifically, the current study will examine the role of resilience and team dynamics in nurses’ experience of MD across experience levels and patient care settings. The Moral Distress Theory framework [2]. Which classifies MD as a construct that requires intervention at multiple levels (i.e., individual, organizational, and healthcare system as a whole), will guide the study.

METHODS

A sequential explanatory mixed method research design was utilized - a methodology that provides a broader overview of MD that cannot be explored with quantitative or qualitative data alone [5]. Following IRB approval, quantitative data was collected from July 2023 to August 2023 via an online survey; qualitative data was collected via interview in September 2023. Eligibility criteria included: current licensure as a registered nurse in the state of Utah (either employed or unemployed), registered nurses who retired within the past five years, age of 18 and older, nurses in any patient care setting, and no restrictions on gender or race. Participants were recruited via Utah’s Division of Occupational and Professional Licensing (DOPL) database. Surveys were completed via REDCap® and interviews were conducted via Vidyo© -- both of which are HIPAA-compliant software. Final recruitment of interviewees was determined through purposive sampling to ensure a variety of patient care settings and experience levels. Incentive was provided for the surveys (i.e., raffle for an Apple iPad©) and interviews (i.e., $30 gift card).

Sample Demographics

A total of 5,000 emails were sent to potential participants and 216 nurses participated in the online survey. Demographic information is presented in (Table 1).

Table 1: Demographic characteristics and questionnaires by acute and non-acute settings.

|

Variable |

Total |

Acute |

Non-Acute |

p |

|

|

N = 216 |

N = 125 |

N = 91 |

|

|

Age: Count, Mean (SD), Median, Min-Max |

200, 38.3 (10.4), 37, 20-70 |

119, 37.1 (9.7), 36, 22-67 |

81, 40.2 (11.2), 38, 20-70 |

0.034*† |

|

Missing: Count (%) |

16 (7.4) |

6 (4.8) |

10 (11.0) |

|

|

Gender |

||||

|

Male |

36 (16.7) |

21 (16.8) |

15 (16.5) |

0.992‡ |

|

Female |

178 (82.4) |

104 (83.2) |

74 (81.3) |

|

|

Missing |

2 (0.9) |

0 (0) |

2 (2.2) |

|

|

Race |

||||

|

White |

192 (88.9) |

110 (88.0) |

82 (90.1) |

0.472§ |

|

Asian |

3 (1.4) |

2 (1.6) |

1 (1.1) |

|

|

Black or African American |

2 (.9) |

1 (.8) |

1 (1.1) |

|

|

Multiple races |

7 (3.2) |

3 (2.4) |

4 (4.4) |

|

|

Other |

3 (1.4) |

3 (2.4) |

0 (0) |

|

|

Missing or prefer not to answer |

9 (4.2) |

6 (4.8) |

3 (3.3) |

|

|

Ethnicity |

||||

|

Hispanic |

12 (5.6) |

5 (4.2) |

7 (8.2) |

0.227‡ |

|

Non-Hispanic |

192 (88.9) |

114 (91.2) |

78 (85.7) |

|

|

Missing or prefer not to answer |

12 (5.6) |

6 (4.8) |

6 (6.6) |

|

|

Degree |

||||

|

Vocational |

11 (5.1) |

5 (4.0) |

6 (6.6) |

0.509‡ |

|

Associate |

79 (36.6) |

42 (33.6) |

37 (40.7) |

|

|

Bachelor’s |

109 (50.5) |

67 (53.6) |

42 (46.2) |

|

|

Master’s |

17 (7.9) |

11 (8.8) |

6 (6.6) |

|

|

Years of Experience |

||||

|

0-5 years |

73 (33.8) |

47 (12.8) |

26 (28.6) |

0.166‡ |

|

6-10 years |

44 (20.4) |

26 (24.8) |

18 (19.8) |

0.854‡ |

|

11+ years |

99 (45.8) |

52 (41.6) |

47 (51.6) |

0.143‡ |

|

Employment Status |

||||

|

Not full time |

54 (25) |

27 (21.6) |

27 (29.7) |

0.176‡ |

|

Full time |

162 (75.0) |

98 (78.4) |

64 (70.3) |

|

|

Age, mean (SD), Median, Min-Max |

38 (10.433), 37, 20-70 |

37.05 (9.680), 38, 20-70 |

40.22 (11.247), 36, 22-67 |

0.034*† |

|

MMD-HP, Mean (SD), Min-Max |

104.29 (63.33), 2-302 |

107.14 (65.91), 2-302 |

100 (59.71), 8-257 |

0.439† |

|

T-TAQ, Mean (SD), Min-Max |

121.06 (8.21), 99-148 |

121.6 (8.08), 103-148 |

120.31 (8.37), 99-139 |

0.259† |

|

CD RISC-10 Mean (SD), Min-Max |

30.62 (4.93), 15-40 |

30.70 (5.16), 15-40 |

30.52 (4.63), 21-40 |

0.792† |

*Statistically significant at p < .05

Note: † = t-test, ‡ = Chi-square test, § = Fisher’s exact test, MMD-HP = Measure of Moral Distress for Health Care Professionals; T-TAQ = Team, STEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire; CD-RISC-10 = Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale.

Data Collection

Initial quantitative data collection occurred through email, with potential participants receiving a consent letter and link to the survey (completed through REDCap® software). The survey included three measures: the Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals scale (MMD-HP), 21 the Connor- Davidson Resilience 10-Item Scale (CD-RISC-10) [6], and the Team STEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (T-TAQ) [7]. All the surveys were carried out based on the STROBE method that includes three types of studies namely, cohort-based, cross- sectional studies. The overall survey took 15 minutes to cover the three aspects and all the questions included in the survey have been listed below.

Qualitative data was then collected through semi-structured interviews. For selection purposes, every interviewee was set an invitation letter at the end of the survey. Further, the sampling was carried out only for the individuals who agreed to the invitation. Twenty-eight participants were purposively sampled to represent a diverse cohort of nurses, who varied in age, education, years of clinical experience, and specialization. The interview questions were prepared based on multiple discussions with experts in the area of field and grief counselors. The interview sessions lasted between 45 to 80 minutes and were steered by a set of open-ended questions that were crafted to elicit comprehensive and detailed accounts of the nurses’ experiences, challenges, and professional perspectives. With consent, all interviews were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed. During the transcription process, rigorous measures were adopted to remove any identifying information and to ensure participant confidentiality

QUANTITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

All analyses were conducted using SPSS© version 28. Moderation analysis utilized the PROCESS package developed by Hayes et al [8]. Due to every survey response being required, there were no missing data for the validated questionnaires. There were however a few missing values in some of the demographic variables. Because the percentages of the missing values out of all observations were very low, even when aggregated for all the variables of interest, the corresponding observations where at least of one of the variables had a missing value were dropped from the analysis that included those variables. For significance testing alpha was set to 0.05. There were 91 non-acute and 125 acute participants. Due to the assumption of homogeneity of variances being violated, as assessed by Levene’s test for equality of variances (p <. 05), we conducted a Welch t-test to determine differences in Moral Distress (MD) between acute and non-acute settings. An inspection of a boxplot determined there were no outliers in the data, and a Shapiro-Wilk’s test ruled out that overall MD scores as well as those for acute and non- acute were normally distributed (p < .001, p < .001, and p = .003, respectively) [9].

We conducted a multiple regression analysis to explore the moderating effect of work experience on the impact of acute settings on MD. The analysis included age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, and level of nursing education as covariates. Observations were independent as assessed by a Durbin-Watson statistic of 2.101 [10]. The errors were homoscedastic, as assessed by visual inspection of a plot of studentized residuals versus unstandardized predicted values. There was no evidence of multicollinearity among the independent variables, as assessed by tolerance values significantly greater than 0.1, or VIF values significantly less than 5. There were no leverage values greater than 0.2 and no values for Cook’s distance above 1. The assumption of normality of residuals was not met, as assessed by a Q-Q Plot [11]. As part of the moderation analysis in PROCESS, we looked at overall significance, variance explained (R2), and pick-a-point method to find out for which points moderation was important [8]. Keeping the covariates unchanged, we then conducted a multiple regression analysis to explore the moderating effects of work experience and acute setting on the impact of resilience on MD.

We conducted a hierarchical multiple regression to examine the moderating effect of resilience on the impact of acuity settings on MD. At the first level, we included the acute setting, work experience and the covariates specified above as the independent variables. The first level was nested in a model that additionally included resilience and team dynamics as independent variables. The second model was nested in yet another level that additional included the interaction between resilience and team dynamics.

QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

We employed Braun and Clarke’s [12] thematic analysis to qualitatively analyze the data from the nurses’ interviews. The research team first engaged in multiple readings of the transcripts, familiarizing themselves with the data to gain a thorough and holistic understanding of its content. Researchers then systematically identified and coded significant features of the data using inductive and deductive coding techniques [13]. In cycle 1 of coding, we coded inductively for the survey questions; in cycle 2, we arranged the codes in a deductive manner. This approach ensured that themes were derived from the data while also being grounded in existing theoretical frameworks. As the analysis progressed, the codes were grouped, and themes began to emerge. The process was recursive, involving repeated visits to the dataset, coded extracts, and the emerging themes, ensuring that the themes were valid and comprehensive. Once solidified, each theme was defined and named. The final step involved selecting pertinent extracts from the dataset, narratively weaving them together to vividly depict and contextualize the themes. The research team maintained the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants throughout the research process.

The integration of quantitative data was achieved through a critical mixed methods process known as “connecting.” This strategy enhanced the rigor of the study by establishing a link between the quantitative and qualitative datasets. It involved intentionally selecting the same individuals who responded to the survey for subsequent interviews, thus ensuring a cohesive examination of experiences across both quantitative and qualitative domains [14]. In this study, connecting was implemented to inform purposive sampling of participants to identify and interview participants of various experience levels who work across a variety of patient care settings. The quantitative findings served as a guiding structure for the subsequent qualitative analysis. In other words, the insights and patterns discovered from the quantitative data shaped how we approached the qualitative analysis, influencing what themes or narratives we looked for and how we interpreted the qualitative responses. This iterative process enhanced the depth and breadth of our understanding of the research question.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

A total of 191 participants completed the online survey. The average age of the participants was 38 years, ranging from 20 to 70 years. The sample was predominantly female (83.2%). Gender distribution showed no statistical variance between the Acute and Non-Acute groups (p = .992). Most participants identified as White (88.9%), and no significant differences in racial composition were observed between the two groups (p = .597). The majority of participants were non-Hispanic (94.1%), and ethnic distribution did not significantly differ between the groups (p = .227). Educationally, participants held diverse degrees, with no significant distinctions between the groups (p = .509). In terms of professional experience, two data sets have been included, one having experience of 0-2 years and the other from 2-5 years and both have been combined to yield the statistical results. Another category includes nurses having experience of more than 11 years grouped as 11+. Employment status revealed that 75.0% of participants were employed full-time, with no significant differences noted between the Acute and Non-Acute groups (p = .176). This comprehensive characterization sets the stage for exploring potential relationships between these demographic factors within the study’s framework. See (Table 2,3) for complete demographic characteristics.

Table 2: Testing the Association of Acuity and Moral Distress and if Work Moderates this Association.

|

|

95% CI |

|||||

|

|

B |

SE |

t |

p |

Low |

Upper |

|

constant |

106.77 |

28.3 |

3.77 |

< .001 |

50.93 |

162.6 |

|

Acute |

-16.35 |

15.74 |

-1.04 |

0.3 |

-47.4 |

14.71 |

|

Work experience 5-10 years |

4.93 |

20.64 |

-0.24 |

0.81 |

-45.65 |

35.79 |

|

Work experience 11+ years |

10.5 |

18.37 |

0.57 |

0.57 |

-25.75 |

46.75 |

|

Acute* Work experience 5-10 years |

31.76 |

25.35 |

1.25 |

0.21 |

-18.26 |

81.78 |

|

Acute* Work experience 11+ years |

29.2 |

20.33 |

1.44 |

0.15 |

-10.92 |

69.32 |

|

Age |

0.94 |

0.55 |

1.73 |

0.09 |

-2.02 |

0.13 |

|

Male |

9.67 |

12.48 |

-0.77 |

0.44 |

-34.3 |

14.97 |

|

Hispanic |

1.48 |

18.33 |

0.08 |

0.94 |

-34.69 |

37.65 |

|

Employment Status |

9.05 |

10.29 |

0.88 |

0.38 |

-11.25 |

29.36 |

|

Degree |

6.04 |

5.23 |

1.16 |

0.25 |

-4.27 |

16.36 |

|

R2 |

|

0.24 |

|

|

|

|

|

Adj R2 |

|

0.06 |

|

|

|

|

|

p < .05 |

|

|||||

Table 3: Testing the Association of Resilience and Moral Distress and if Work and Acuity Moderates this Association.

|

|

95% CI |

|||||

|

|

B |

SE |

t |

p |

Low |

Upper |

|

constant |

135.68 |

71.63 |

1.89 |

0.06 |

5.64 |

277.00 |

|

Resilience |

-1.36 |

2.15 |

-0.63 |

0.53 |

-5.6 |

2.88 |

|

Work experience 5-10 years |

-42.55 |

75.83 |

-0.56 |

0.58 |

-192.16 |

107.06 |

|

Work experience 11+ years |

12.36 |

65.76 |

0.19 |

0.85 |

-117.39 |

142.1 |

|

Acute |

5.74 |

59.34 |

0.1 |

0.92 |

-111.34 |

122.81 |

|

Resilience* Work experience 5-10 years |

2.07 |

2.44 |

0.85 |

0.4 |

-2.74 |

6.87 |

|

Resilience* Work experience 11+ years |

0.68 |

2.13 |

0.32 |

0.75 |

-3.51 |

4.88 |

|

Resilience* Acute |

-0.04 |

1.92 |

-0.02 |

0.98 |

-3.83 |

3.74 |

|

Age |

-1.05 |

0.56 |

-1.88 |

0.06 |

-2.15 |

0.05 |

|

Male |

-5.78 |

12.51 |

-0.46 |

0.65 |

-30.46 |

18.91 |

|

Hispanic |

-1.13 |

14.45 |

-0.08 |

0.94 |

-29.64 |

27.39 |

|

Employment Status |

-3.54 |

7.97 |

-0.44 |

0.66 |

-19.26 |

12.18 |

|

Degree |

8.28 |

5.34 |

1.55 |

0.12 |

-2.25 |

18.81 |

|

R2 |

|

0.07 |

|

|

|

|

|

Adj R2 |

|

0.006 |

|

|

|

|

|

p < .05 |

|

|||||

Patient Care Setting, Experience Level, and Moral Distress

Nurses practicing in acute settings did not report higher levels of MD (M = 100.37, SD = 59.72) compared to those in non-acute settings (M = 107.1, SD = 65.9), t (203.98) = -.787, p

= .432. Moral distress can arise when nurses face situations in which their ethical convictions are at odds with the realities of healthcare practice. “I feel like there’s moral distress in most areas of nursing,” noted one nurse (#1646, age 39, pediatric ICU, 11+ years). In defining the nature of this distress, another nurse (#487, age 22, pediatric and adult LTAC, less than 2 years) states, “It’s not burnout, it’s moral distress,” drawing a line between the emotional impact of workload and the deeper ethical conflicts experienced. These reflections highlight the moral and emotional challenges faced by nurses.

The overall multiple regression model, including main effects and the interaction term, was not statistically significant in predicting MD, F (10, 179) = 1.1268, p > .05, R² = .3445.

Specifically, acuity and work experience did not significantly predict MD (Work 5-10 X Acute: F (1, 179) = 1.2529, p = .2119;

Work 11+ X Acute: F (1, 179) = 1.4363, p = .1527), indicating that work experience did not significantly moderate the relationship between the acute setting and MD. The realm of patient care presents nurses with a spectrum of challenges, ranging from ethical dilemmas and advocacy for patient needs, to the emotional intricacies of dealing with patients and their families. Nurses often encounter MD when their ability to advocate effectively for their patients is hindered by systemic barriers and lack of support.

“I think a lot of moral distress comes when I feel that I’m advocating for my patient and I am not able to get the support that I need…from the rest of the team,” shared one nurse (#2436, age 29, burn trauma ICU, 2-5 years), highlighting these strains.

Moreover, the interactions with patients and their families add another layer of complexity, ranging from supportive to confrontational, further impacting nurses’ emotional well-being. A nurse (#1140, age 64, adult ICU, 11+ years) highlighted the repercussions of these challenges, stating, “…what’s been going on for a long time is the abuse that happens verbally and physically from patients to nurses and techs. I mean, it’ll make you cry, some of the stories you hear where nurses and techs getting punched, and broken teeth, broken ribs…a year-and-a-half ago…where a patient kicked a nurse in the stomach. She was pregnant. She lost her baby. And you’re expected – too bad. That goes with the job, you’ll be back at 6:00 in the morning for your next shift, you know? That’s unacceptable.”

Nurses often encounter a complex blend of ethical dilemmas and inner conflicts. They strive to maintain ethical and professional integrity while facing challenging situations. For instance, one nurse (#2626, age 47, outpatient primary care, 11+ years) stated, “If I’m scheduled, I’m there, I don’t call in sick,” illustrating the significance of responsibility in their role. Yet, they often face ethically complex situations, such as seeing “99-year- old grandma from a nursing home is a full code everything” (#1646, age 39, pediatric ICU, 11+ years) while grappling with the thoughts, “What the hell do you think we’re doing, then?” (#1646, age 39, pediatric ICU, 11+ years) when witnessing discrepancies in family wishes versus patient outcomes. Additionally, nurses often grapple with internal conflicts between personal beliefs and professional obligations.

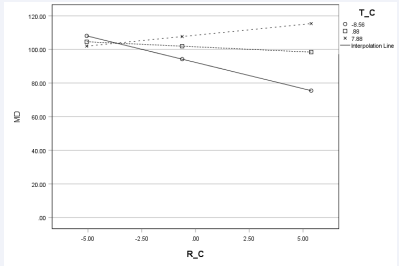

Team Dynamics and Work Environment

Model 3 demonstrates a significant interaction between CD-RISC-10 and T-TAQ scores was statistically significant, F (11, 178) = 5.53, p = .019. Scores on anxiety (T-TAQ) scale (M = 121.06, SD = 8.21) and resilience (CD-RISC-10) scale (M = 30.62, SD = 4.93) did not differ significantly between acute and non-acute settings. This suggests that team dynamics moderate the association between a nurse’s level of resilience and their experience of MD. The pick-a-point approach using the Johnson- Neyman [15] technique at 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles found that higher resilience was associated with significantly lower MD (b = -3.15, p = .029) at lowest levels of team dynamics (T-TAQ = -8.5600). This suggests that individuals with lower resilience may experience a significant decrease in MD as their resilience increases. However, this significant relationship did not hold when perceptions of team dynamics were average (T-TAQ = 0.88, p = .503) or higher (T-TAQ = 7.88, p = .28).

There was no statistically significant interaction between work and team dynamics or work and resilience. As such, Model 3 was selected as the most parsimonious model. Despite the significant interaction, it is important to note that the final regression model explained only a modest portion of the variability in MD (adjusted R2 = .088 with the interaction contributing 0.028). This suggests that, although resilience and team dynamics are important, there are other key factors that influence MD in meaningful ways.

Nurses consistently express concerns regarding a disconnect between ground-level staff and management, particularly those in higher administrative roles. This disconnect occurs not only in physical absence or limited interaction, but also in a perceived lack of understanding, support, and advocacy. Nurses report feeling overlooked and undervalued, and that their concerns are often unrecognized or inadequately addressed. As one nurse (#4306, age 24, inpatient med-surg float pool, 2-5 years) stated, “It’s sickening sometimes how management will toy with their employees.” Issues such as staffing shortages and pay disparities compound these frustrations. Another nurse (#401, age 24, outpatient oncology, less than 2 years) described the frustration, saying, “Okay, if we’re all experiencing these issues then why aren’t we doing anything about it?”

Nurses frequently reported issues related to staffing. These problems range from high turnover rates (i.e., which are often attributed to organizational constraints), to the MD caused by insufficient staffing, particularly in specialized areas. Such conditions lead to an overextended workforce, with potential negative outcomes for patient care quality and the well-being of the healthcare workers. Nurses commonly report feeling overburdened by excessive workloads, which challenge their ability to maintain a healthy work-life balance. As a nurse (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) stated, “This is not an 8:00 to 5:00 job. This is a work until it’s done job.” The deficit in staffing not only affects job satisfaction but also poses safety concerns for the staff.

The dynamics of team interactions within healthcare settings can significantly impact the workplace atmosphere and the quality of patient care. This theme focuses on the negative aspects of team dynamics, such as gossip and confrontations. These issues often lead to disharmony within teams, affecting individual relationships and overall team functionality. As expressed by a nurse (#487, age 22, pediatric and adult LTAC, less than 2 years), “I definitely think there’s a few nurses on the unit that don’t pull their load,” drawing attention to the challenges of unequal contributions.

Another nurse (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) asserted a stance against disruptive behavior, saying, “I don’t tolerate gossip. It’s my No. 1 rule.” These sentiments illustrate the challenges in achieving harmonious team dynamics. Instances of disagreements escalating to Human Resources involvement and mistrust due to unfair evaluations are also noted, demonstrating the complexity of interpersonal relationships in healthcare. In contrast, the positive aspects of team dynamics in healthcare, such as effective collaboration and support among colleagues, contributes to patient care and workplace satisfaction. Nurses discussed situations where team members work cohesively and engage in open communication and mutual support. A nurse (#3162, age 29, adult med-surg floor, 6-10 years) described their situation, “I feel like there’s a lot of positive collaboration where I work. There’s a very overwhelming sense of, we’re in this together.” These dynamics are crucial for creating a supportive work atmosphere and can directly influence patient outcomes positively.

Nurses emphasize the need for practical and emotional support and the importance of camaraderie and effective communication among colleagues. Having a network of support allows for a foundation of mutual understanding and assistance. For example, a nurse (#1018, age 34, labor and delivery, 6-10 years) shared, “But yeah, it does in those instances when people have said things to me about how much I work or things like that, it makes me feel less part of the team and less likely to want to continue working there or things like that,” underlining the impact of positive team dynamics on individual well-being. Additionally, one nurse (#1646, age 39, pediatric ICU, 11+ years) said “how much can you expect your staff to continue to be resilient if the system is broken?”- pointing to the critical balance between individual fortitude and the need for systemic support.

Healthcare environments often involve complex interpersonal dynamics, shaped by varying power dynamics, roles, and experience levels. Nurses, from novices to veterans, must navigate this landscape. For instance, a nurse (#371, age 53, inpatient wound care, less than 2 years) expressed, “A lot of the RNs kind of look down on the LPNs,” highlighting a hierarchy within nursing ranks. At the same time, however, there is a collective mutual respect and understanding among the nurses. As noted by one nurse (#4611, age 26, outpatient procedures, 2-5 years), “But we do keep trying to break that barrier down and we have lots of physicians that do a good job of treating you as an equal, basically as the team.” The landscape of communication in healthcare sways between effective clarity and challenging ambiguity. On one hand, systems like nursing informatics represent advanced communication tools. In contrast, issues like miscommunication due to dominant personalities and gaps in established protocols also persist. For instance, a nurse (#4262, age 26, adult emergency department, 2-5 years) highlights the importance of constructive feedback, “If I see that you’re on your phone... I want you to improve.”

In contrast, another nurse points out practical issues, such as the infrequent implementation of theoretically proposed debriefs, stating, “So, they’re supposed to do a debrief, obviously. But I’ve never actually heard of anyone doing one” (#484, age 27, labor and delivery, less than 2 years). These accounts show the varied nature of communication experiences in healthcare, ranging from efficient and structured, to unpredictable and inconsistent. The concept of empowerment in the workplace extends beyond a mere buzzword. It is a critical element in modern organizational dynamics. For nurses, empowerment means entrusting employees with autonomy and recognizing their contributions, and fostering an environment where they can excel. This approach boosts confidence and instills a sense of belonging among staff. A team leader’s comment (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) encapsulates this: “I don’t even know what they do every day. I empower them.” Leadership played a key role, balancing empowerment with the necessity of guidance (Table 4,5).

Table 4: Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting MMD_HP (N = 190).

|

|

Model 1 |

|

|

Model 2 |

|

|

Model 3 |

|

|

|

Variables |

B |

SE B |

β |

B |

SE B |

β |

B |

SE B |

β |

|

(Constant) |

94.103 |

27.129 |

|

96.432 |

27.204 |

|

102.34 |

26.983 |

|

|

Age |

-0.976 |

0.545 |

-0.174 |

-0.907 |

0.547 |

-0.162 |

-0.862 |

0.541 |

-0.154 |

|

Acute |

3.838 |

9.087 |

0.032 |

3.194 |

9.096 |

0.026 |

3.718 |

8.986 |

0.031 |

|

Male |

-7.042 |

12.373 |

-0.044 |

-3.685 |

12.596 |

-0.023 |

-2.865 |

12.444 |

-0.018 |

|

Hispanic |

2.707 |

18.279 |

0.011 |

4.35 |

18.281 |

0.018 |

3.712 |

18.056 |

0.015 |

|

Full Time |

7.128 |

10.227 |

0.052 |

5.285 |

10.292 |

0.039 |

0.417 |

10.373 |

0.003 |

|

Bachelor’s or more |

6.34 |

5.226 |

0.09 |

5.198 |

5.269 |

0.074 |

4.579 |

5.21 |

0.065 |

|

Work experience 5-10 years |

15.813 |

12.883 |

0.108 |

17.363 |

12.908 |

0.118 |

12.263 |

12.931 |

0.084 |

|

Work experience 11+ years |

29.289 |

13.156 |

.245* |

29.115 |

13.15 |

.244* |

23.057 |

13.239 |

0.193 |

|

Resilience |

|

|

|

-0.529 |

0.913 |

-0.044 |

-0.842 |

0.911 |

-0.07 |

|

Team Dynamics |

|

|

|

0.887 |

0.566 |

0.12 |

0.973 |

0.56 |

0.132 |

|

Resilience*Team |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.269 |

0.114 |

.178* |

|

R2 |

|

0.045 |

|

|

0.06 |

|

|

0.088 |

|

|

Adj R2 |

|

0.004 |

|

|

0.007 |

|

|

0.032 |

|

|

*p <.05. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5: Codebook.

|

Themes |

Definition |

Exemplar Quote |

|

Burnout in Nursing |

Nurses experience burnout characterized by exhaustion due to systemic issues, affecting care and well-being. |

When they were cutting staff, and I was expected to do more than any one person could do. I was doing four and five jobs at a time. (#1445, age 37, adult emergency department, 11+ years) |

|

Moral Distress and Ethical Challenges in Nursing |

Nurses face moral distress when their ethical values conflict with their professional environment, leading to emotional turmoil. |

That felt distressing. I came home. I was very upset at how hard that situation had been. (#542, age 43, adult med-surg, less than 2 years) |

|

Gaps in Nursing Education and Real-World Preparedness |

There is a gap between nursing education and the actual demands of healthcare work, causing stress and a sense of unpreparedness among nurses. |

I believe so many school systems are poorly equipped to teach real- world subjects. (#1140, age 64, adult ICU, 11+ years) |

|

The Imperative of Ongoing Professional Development and Support in Nursing |

Continuous learning and mentorship are essential for nurses to remain effective and confident in the ever-changing healthcare landscape. |

But yeah, I think that would be a good thing to – because I feel like the things that I’ve learned I’ve just learned on the job and watching people... (#1458, age 38, adult ICU, 6-10 years) |

|

The Multifaceted Challenges of COVID-19 on Nursing |

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted nursing, introducing physical strain, emotional stress, burnout, and the challenge of operating in a politicized healthcare context. |

So, I haven't had a ton of them, but especially during COVID I noticed I was consistently put in situations where I wasn't comfortable just due to the needs of the hospital. (#1018, age 34, labor and delivery, 6-10 years) |

|

Management Disconnect & Systemic Challenges |

The perceived gap between ground-level nursing staff and higher administrative roles, characterized by feelings of being overlooked, undervalued, and unsupported. |

These are the things when I see resources being pulled that is difficult for me. (#542, age 43, adult med-surg, less than 2 years) |

|

Staffing Strains & Workplace Realities |

The impact of insufficient staffing on patient care quality, burnout, and work-life balance for healthcare workers. |

We have a huge turnover rate because of that… I feel like it does not make sense. (#462, age 22, adult med-surg, less than 2 years) |

|

Professional Interactions & Team Discord (Negative Side) |

The impact of disharmony and unprofessionalism on team unity and patient care within healthcare environments. |

She’s making comments to me, but she’s making really terrible comments to this other coworker. (#48, age 42, outpatient palliative care, 11+ years) |

|

Team Dynamics, Collaboration, and Support in Healthcare (Positive Side) |

The positive effects of teamwork, cooperation, and support on patient care and healthcare professional satisfaction. |

... I really like working outpatient, I feel like we're on a team and… we each have our own roles that are defined, but…because we are a team, we're so willing to help each other out. (#401, age 24, outpatient oncology, less than 2 years) |

|

Support Systems and Interpersonal Relationships in Healthcare |

The role of emotional and practical support in bolstering nurse resilience and ensuring a sense of validation and connection in healthcare settings. |

But yeah, it does in those instances when people have said things to me about how much I work or things like that, it makes me feel less part of the team and less likely to want to continue working there or things like that. (#1018, age 34, labor and delivery, 6-10 years) |

|

Navigating the Complex Landscape of Patient Care: Advocacy, Ethics, and Emotional Dynamics |

The complexities of patient care involving ethical decisions, emotional involvement, advocacy efforts, and the push for systemic reform. |

I think a lot of moral distress comes when I feel that I’m advocating for my patient, and I am not able to get the support that I need…from the rest of the team. (#2436, age 29, burn trauma ICU, 2-5 years) |

|

Desensitization and Its Impacts on Patient Care |

The consequences of workplace pressures like bullying and peer pressure in healthcare, and their impact on professional well-being and patient care. |

I think we all do, to some degree. Otherwise, we can’t stay in the profession. (#2626, age 47, outpatient primary care, 11+ years) |

|

Addressing Bullying and its Aftermath in Healthcare |

The dynamics of bullying in healthcare settings and the ensuing impact on individuals and team relations. |

Another thing that has affected me in the past... is bullying. (#2626, age 47, outpatient primary care, 11+ years) |

|

Journey of Resilience: From Challenges to Growth in Healthcare |

The growth and adaptation of nurses within the challenging landscape of healthcare. |

I feel like I’m a much stronger person than I was three years ago. (#4262, age 26, adult emergency department, 2-5 years) |

|

©Coping Mechanisms and Self- Care in Healthcare |

The diverse strategies nurses employ to manage the demands and stressors of healthcare work. |

Dissociate. Compartmentalize, that’s maybe a better word. (#698, age 39, home health and hospice, 2-5 years) |

|

Ethical Integrity and Inner Conflict in Nursing |

The ethical challenges and internal conflicts nurses face while maintaining professional standards. |

So, yeah. Something like that where you don’t feel empowered to pump the brakes and delve into the ethical questions. It’s very challenging. (#698, age 39, home health and hospice, 2-5 years) |

|

Navigating Work-Life Harmony in Healthcare |

Investigating how healthcare professionals, especially nurses, manage the balance between their professional duties and personal life. |

...it is okay to maybe sometimes do things for myself or not feel like I have to just bust myself to be valued. (#401, age 24, outpatient oncology, less than 2 years) |

|

Bridging the Hierarchical Divide: Interpersonal Dynamics in Healthcare |

The dynamics of power, roles, and experience within healthcare and the quest for mutual respect. |

I think the biggest problem is still between nurses and physicians. It’s something that will probably always be there. (#4611, age 26, outpatient procedures, 2-5 years) |

|

Nurturing Autonomy: The Journey of Empowerment in the Workplace |

The critical importance of empowerment, autonomy, and leadership in the modern workplace. |

We have leadership that do empower us to make those decisions. (#1631, age 38, educator, 11+ years) |

|

Communication: Between Clarity and Chaos |

The spectrum of communication in healthcare, from effective exchanges to the challenges posed by system gaps and dominance. |

Our manager doesn't really – doesn't communicate very well... (#4969, age 27, outpatient urgent care, 2-5 years) |

|

Advocacy: From the Wards to the Halls of Change |

The vital role of advocacy in nursing, dedicated to upholding patient welfare and professional interests |

And my ultimate thesis with respect to healthcare workers is that if you’re advocating for healthcare workers, you’re advocating for patients. It’s synonymous. (#698, age 39, home health and hospice, 2-5 years) |

Resilience and Coping

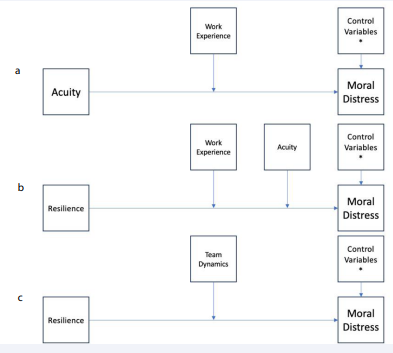

Although the overall model, which aimed at determining whether resilience predicts MD and testing whether Team Dynamics was a moderator, did not significantly predict MD, F(11, 178) = 1.71, p = .114, explaining 8.71% of the variance in MD (R² = .0871), the interaction term between resilience and teamwork was significant, B = .27, SE = .11, t = 2.35, p = .02. This suggests that the effect of resilience on MD is moderated by teamwork, such that lower levels of teamwork amplify the influence of resilience on reducing MD. Conditional effects analysis at the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles of teamwork revealed that the effect of resilience on MD was significantly negative at the 16th percentile of team dynamics (B = -3.12, SE = 1.43, p = .03), non-significant at the median (B = -.59, SE = .89, p = .51), and positive but non- significant at the 84th percentile (B = 1.2840, SE = 1.18, p = .28). These findings indicate that higher resilience is significantly associated with lower MD when team dynamics are low. See (Figure 1) for statistical model.

Figure 1: Conceptual frameworks for analysis predicting moral distress in nurses with various inclusion of various moderators.

- Work experience is the moderating variable and acuity is the independent variable.

- Work experience and acuity as moderating variables and resilience as the independent variable.

Team dynamics as moderating variables and resilience as the independent variable.

The healthcare environment presents nurses with challenges that profoundly impact their emotional and professional lives. Resilience in this context involves not only recovery but also significant growth. Nurses frequently find themselves in situations where they must balance distressing patient care scenarios with complex workplace dynamics. This process fosters a journey of resilience that is characterized by personal and professional development. Nurses report gaining more self-awareness and confidence, learning to set boundaries and prioritize mental health. One nurse (#1140, age 64, adult ICU, 11+ years) summarized, “They’ve [resilience and coping strategies] become more solid... it’s made me more wise and caring to have to go through all this.”

Nurses face a range of emotional, moral, and situational challenges inherent to their high-stress work environment. “I vent a lot to people,” one nurse (#487, age 22, pediatric and adult long-term acute care, less than 2 years) explained, highlighting the need for emotional release in such a demanding setting. To manage these challenges, nurses employ various coping mechanisms. Some find solace in nature, one nurse (#698, age 39, home health and hospice, 2-5 years) described: “Being in nature is the antithesis of the antagonistic stimulus I faced at the hospital.” Humor and open dialogue with peers were also common strategies. Hobbies, professional support networks, and time for self-reflection were vital tools that nurses used to build resilience, prevent burnout, and support their personal development.

Nurses face the ongoing challenge of balancing work obligations with personal life. This balance involves internal conflicts and societal pressures. A nurse (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) described this struggle as, “It’s actually I feel like I’m at war with myself”, highlighting the internal tug-of-war they experience. Systemic pressures and organizational demands further complicate this balance. The same nurse (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) noted, “We’re still doing these things. But the reason is - I truly believe the reason is: if we are going to set an expectation that we can have a work/life balance boundary, then we have to rethink staffing.” Despite these challenges, there is an emphasis on the importance of self-care and setting personal boundaries.

Nursing Education and Curriculum

There is a discrepancy between the curriculum in nursing education and the practical realities encountered in healthcare settings on a daily basis. Reports from nurses indicate a sense of being underprepared for the complexities of clinical practice. As one nurse (#1018, age 34, labor and delivery, 6-10 years) disclosed, “So, it was just hard knowing that I wasn’t actually qualified to do those things, yet here I was put in this situation,” highlighting the gap between educational preparation and the realities of the job’s demands. This sentiment was echoed by another nurse (#1445, age 37, adult emergency department, 11+ years) who observed a lack of resources in practice compared to what was taught: “And so, I knew what the patient was supposed to have. And then, you go into the actual field and you don’t have any of the resources.” These findings suggest that although a nursing education establishes a foundation, there is a significant gap that leaves nurses feeling as though they are not fully equipped to handle the demands of their patients and the healthcare environment (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Resilience and Team Dynamics interaction predicting Moral Distress. Note: Graph of interaction between resilience (centered) scores and team dynamics (centered) predicting Moral Distress (MD). Resilience is most strongly associated with lower MD when team dynamics is low, but this association weakens as team dynamics increases. The three points on the graph represent the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles with the pick-a-point Johnson-Neyman approach

The analysis indicates a critical need for ongoing professional development in nursing. Continuous learning and training are essential for nurses to adapt to the evolving healthcare landscape. This is not only about enhancing current competencies, but also about fostering confidence and resilience in their roles. One nurse (#1458, age 38, adult ICU, 6-10 years) suggested that nursing schools and new nurse programs could benefit from integrating more direct, hands-on experiences, “… I think that would be a great thing to make sure nursing schools are doing or new nurse programs are doing.” The value of continuous education is further validated by another nurse (#3074, age 34, educator full time and NICU part time, 6-10 years) who cited the positive impact of additional certification: “So, it’s a certified healthcare simulation educator certification. And that one focuses a lot on psychological safety in learning environments and what do you do to create that in learning environments. And it really focuses on how… you identify…external stressors, how those impact our perspectives on situations. And I think that’s what taught me more about the moral distress.” These insights point to the importance of not just foundational education but also the application of continued professional development and the availability of support systems within the workplace.

Consequences of the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a profound impact on nursing that resulted in a number of physical and psychological challenges. The implementation of strict protective measures resulted in physical strain, discomfort, and fatigue. The situation also escalated emotional and psychological distress among healthcare workers. As one nurse (#1445, age 37, adult emergency department, 11+ years) stated, “I think the most distressing part of the pandemic for me was watching how politicized the pandemic got.” Another nurse (#1140, age 64, adult ICU, 11+ years) detailed both emotional and verbal abuse during the pandemic, “…healthcare facilities, not standing by their nurses and techs, frontline workers…There was abusive - mainly verbally abusive - patients and families during COVID demanding these strange treatments and calling us horrible things for trying to save their lives.” This demonstrates the complex array of stressors that healthcare workers faced, including the management of patient anxiety, heightened stress levels, and a rapid increase in burnout rates. The pandemic disrupted the conventional pace of professional fatigue and precipitated a sharp rise in its incidence. Nurses also contended with the emotional challenges posed by patient isolation and restrictive visitor policies.

Repeated exposure to traumatic or challenging situations in healthcare lead to desensitization among some nurses. Desensitization may reduce their emotional responses to situations that are otherwise distressing. This phenomenon can be seen as a protective mechanism or a potential barrier to empathetic patient care. “I think we all do, to some degree. Otherwise, we can’t stay in the profession,” a nurse (#2626, age 47, outpatient primary care, 11+ years) reflected, indicating the prevalence of this coping strategy. At the same time, however, this desensitization raises concerns about maintaining compassionate care. Despite this emotional coping, the underlying commitment to patient welfare remains, as another nurse (#371, age 53, inpatient wound care, less than 2 years) highlighted: “I still cry when something is going wrong. I still care and I want to help people.”

Bullying and Burnout

Nurses report a spectrum of experiences with bullying, ranging from subtle peer pressures to more overt cases. These incidents often lead to increased stress, negative dynamics at the workplace, and sometimes, the need for formal reporting or disciplinary actions. The effects of bullying extend beyond the individuals involved and may impact the overall work environment, quality of care, and mental well-being of healthcare staff. As one nurse (#2626, age 47, outpatient primary care, 11+ years) shared, “Another thing that has affected me in the past... is bullying.” Another nurse (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) reflects resilience despite these challenges: “I have observed it. I have not been the victim, but I don’t have a victim mentality, so maybe I have, and I just don’t recognize it.”

Burnout among nurses is characterized by significant emotional and physical exhaustion [16]. “They’ve gotten a lot worse. It’s more of those unhealthy coping mechanisms because you work your three shifts, and you come home, and you’re exhausted,” one nurse (#4306, age 24, inpatient med-surg float pool, 2-5 years) remarked, indicating the personal toll of long work hours. Another nurse (#3283, age 42, inpatient transplant floor, 11+ years) pointed to systemic issues and noted the widespread recognition of burnout: “Even though everyone’s burnout scores are through the roof, hopefully they at least say, ‘I had a good manager that spoke up for me, even if we didn’t get anything done.’” Together, these accounts underscore the prevalence of burnout and its impact on nurses’ well-being and patient care.

The role of advocacy in nursing is crucial, often balancing patient care and personal well-being. Nurses frequently emphasize the importance of advocacy, as one nurse (#4306, age 24, inpatient med-surg float pool, 2-5 years) reflects on the potential of their actions to benefit others: “I’m hoping that this can be a tool used for other nurses.” Yet, the challenge of advocating for oneself is frequently overshadowed by the focus on patient care. The importance of experience in empowering nurses to voice concerns is evident. Advocacy extends beyond individual efforts to encompass the broader healthcare context. As one nurse (#698, age 39, home health and hospice, 2-5 years) remarks, “If you’re advocating for healthcare workers, you’re advocating for patients.”

DISCUSSION

Manifestations of MD in nurses can vary, encompassing psychological feelings of frustration, guilt, and inner conflict. [17]. In the current study, nurses conveyed their experiences of burnout, noting a perceived deficiency in their nursing education, grappling with a disconnect between themselves and management, and contending with persistent systemic challenges. They articulated the origins and repercussions of desensitization, shedding light on the intricate nature of patient care and its accompanying emotional complexities. Recognizing and addressing MD is crucial for fostering a supportive work environment that prioritizes ethical decision-making while preserving the well-being of nurses [18].

Moral distress can significantly influence team dynamics within a healthcare setting, as it can give rise to complex interpersonal challenges among staff. 23 The reverse is also true as team dynamics can affect the level of MD experienced by nurses, either positively (i.e., through collaborative and respectful interactions) or negatively (i.e., through bullying) [19]. Studies by Rushto, et al [20]. Highlighted that supportive team environments and effective communication strategies could significantly reduce moral distress. They found that teams practicing open dialogue and shared decision-making were better equipped to handle ethical dilemmas, leading to reduced levels of moral distress. When healthcare professionals experience MD, it can lead to strained communication, decreased collaboration, and in turn, less effective patient care. The divergence of individual values and ethical perspectives within a team may result in tension, which can make it difficult to establish a unified approach to patient care. This is consistent with Epstein and Hamric [21]. Who found that moral distress among nurses often resulted in poor communication and reduced willingness to engage in teamwork. Effective teamwork requires open dialogue and shared decision- making, but MD can create barriers to these essential components. As noted by Epstein and Hamric [21]. Unresolved moral distress can lead to burnout, which further impacts communication and collaboration among teams. Therefore, addressing and managing MD within the team context is crucial for fostering a collaborative environment where healthcare professionals can collectively navigate ethical dilemmas, ensuring optimal patient care and preserving the well-being of the entire healthcare team [22-28].

Although MD can also impact nurses’ resilience; the nurses’ responses indicated that resilience may also act as a protective factor. Resilience, the ability to bounce back from challenges and adversity, becomes particularly crucial when nurses are faced with the emotional strain of MD. Cultivating resilience can serve as a protective force against the negative effects of MD. As some of the nurses noted, although resilience techniques and gestures like pizza parties can provide temporary relief, the core solution lies in addressing the underlying systemic issues. These results are consistent with Mealer, et al. [29] who found that nurses experiencing high levels of moral distress reported lower resilience levels, highlighting the adverse effects of MD on psychological well-being. However, they also noted that resilient nurses were better equipped to cope with MD, and that resilience acts as a protective factor. Similarly, Rushton, et al. [30] emphasized the importance of resilience in mitigating the negative effects of moral distress, such that nurses with higher resilience levels were more likely to find meaning in their work and were better able to manage ethical dilemmas, supporting the idea that resilience serves as a protective buffer. Together, these results suggest that a resilient mindset empowers healthcare providers to maintain a sense of purpose, navigate moral complexities with greater efficacy, and sustain their commitment to ethical patient care.

As demonstrated in this study, team dynamics moderate the association between a nurse’s level of resilience and their experience of MD. This is consistent with Hart, et al. [31] who found that cohesive team environments positively influenced nurses’ resilience and reduced the impact of MD. Specifically, team support and collaborative practices were shown to buffer the effects of moral distress, similar to the findings of the current study. Therefore, organizations need to prioritize creating a supportive work environment and fostering positive team dynamics. A workplace that fosters support and provides essential resources allows nurses to confront challenges with a sense of security, promoting a resilient mindset. Positive team dynamics play a pivotal role by encouraging collaboration and mutual support among colleagues, creating a shared resilience that eases the emotional burden of MD. More specifically, nurses suggested that higher adequate compensation would not only enhance the nurses’ hard work and ability to deliver quality care but would also address financial stressors and enhance their overall well-being and fortify their emotional resilience. This is consistent with Aiken, et al. [32] who found that competitive compensation was linked to higher job satisfaction and lower burnout rates among nurses; adequate financial rewards were shown to contribute to nurses’ overall well-being and ability to cope with job-related stress, aligning with the current study’s findings. Additionally, many nurses expressed that adequate staffing levels are crucial in preventing burnout and fatigue and enabling nurses to manage their workload effectively and deliver quality care. By prioritizing these systemic factors, healthcare organizations not only alleviate MD but also establish a foundation for sustained resilience, empowering nurses to navigate the demands of their profession with strength and professional fulfillment.

Results demonstrated no significant difference in MD between nurses practicing in acute settings and non-acute settings. Nurses in both acute and non-acute settings may encounter MD triggers - they just may manifest differently in each setting. In acute settings, such as emergency departments or critical care units, MD often arises from time-sensitive decisions, resource constraints, and increased stress and tension. Nurses may grapple with ethical dilemmas related to the allocation of life-saving treatments and the pressure to make quick decisions in high-stakes situations. As noted in McAndrew et al. [33] nurses in acute settings frequently experience MD due to the urgency of clinical decisions, resource limitations, and the emotional burden of critical care. The urgency inherent in acute care settings necessitates seamless teamwork and effective communication; however, the pressure to make swift decisions can strain team dynamics, potentially exacerbating MD. Recognizing the critical role of teamwork in addressing MD is essential in acute settings, emphasizing the need for supportive team structures and clear communication to navigate the intricacies of patient care in acute settings as well as uphold the well-being of nurses and healthcare professionals.

In contrast, nurses working in non-acute settings, like long- term care or outpatient clinics, may experience MD stemming from persistent ethical concerns over issues such as end-of-life care and communication with patients and families. As noted in Ulrich, et al. [34] MD in non-acute settings may stem from prolonged exposure to patient suffering, end-of-life care decisions, and insufficient resources for ongoing patient needs. The interplay with team dynamics in non-acute settings may involve prolonged decision-making processes, requiring sustained collaboration; MD can lead to internal conflicts and hinder a cohesive approach. Ulrich, et al. [34] found that in non-acute settings, strategies such as regular team meetings, ethics discussions, and peer support groups were effective in reducing MD. Notably, the findings of this study demonstrated that better, well-rated, and higher dynamics, coupled with high resilience, are associated with decreased MD. Specifically, team dynamics play a crucial role in shaping the response to MD, as effective communication and shared decision-making are integral components of patient care. Establishing a supportive team environment that encourages open dialogue, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to patient care is essential in mitigating the impact of MD in non- acute settings. Understanding and addressing MD in acute and non-acute settings is vital for fostering resilient and effective teams, ensuring that nurses can navigate MD collaboratively while maintaining the quality of patient care.

A surprisingly large number of 191 participants were willing to conduct an interview. This is likely due to the recruitment email where the principal investigator identified as a nurse and scientist who has experienced MD and burnout. The willingness to participate clearly demonstrates that nurses want to tell their story and that being able to do so was an opportunity to process their journey and potentially heal. Traumatic events could have been reflected upon, participants may have not benefitted from the study, but they may have benefitted from sharing their story and benefitting the profession and health care in general by sharing. During the interviews, many interesting insights emerged, highlighting the multifaceted and complex nature of the nurse experience in today’s healthcare system. One nurse shared that they were able to maintain their resiliency and sensitivity and not succumb to burnout due to their profound faith in God. Interestingly, several nurses shared that they enjoyed listening to loud music after shifts, suggesting a unique, but shared, coping mechanism within the nurse profession. Another coping mechanism that emerged was defaulting to morbid humor.

Due to the nature of their work, nurses shared that, although they feel apathetic toward the larger healthcare organization, they feel strongly bonded to their coworkers through their shared trauma experience. Many nurses expressed that the nursing school curriculum needs to prioritize the emotional aspect of the profession and better prepare nurses for the emotional inevitabilities of the job. Once hailed as heroes during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses expressed a shift in societal perception. As the initial admiration waned, they are no longer viewed as heroes, and are left navigating a complex and evolving professional landscape. Though primarily a female sample, male nurses reported less bullying on the job, with one even identifying his gender as a form of privilege within the profession. Overall, the interviews illuminated a rich tapestry of coping mechanisms, challenges, and reflections, shedding light on the multifaceted world of nurses in today’s healthcare system.

The prospect of transforming MD into post-traumatic growth represents a compelling avenue for the evolution of healthcare professionals. Although MD can impose significant emotional strain, the resilience inherent in nurses may pave the way for personal and professional growth. By acknowledging and actively processing the moral challenges faced in healthcare settings, nurses can cultivate an awareness of their values and ethical principles. The experience of navigating MD may serve as a catalyst for increased empathy, improved coping mechanisms, and a deeper understanding of the complexities within the healthcare landscape. Fostering a culture that recognizes the potential for post-traumatic growth arising from MD is integral to empowering healthcare professionals to overcome the adversities they face, emerging stronger and more resilient in their commitment to ethical and compassionate care.

There is an urgent need to enhance the preparation of nurses to cope with the emotional and MD inherent in their profession. While nursing school and training programs equip nurses with essential technical skills, the emotional toll of healthcare work is often underestimated and under acknowledged. Nursing education should place greater emphasis on emotional intelligence, resilience-building, and coping strategies, ensuring that nurses are equipped not only with medical expertise but also the emotional fortitude to navigate complex ethical dilemmas. By acknowledging and addressing the emotional and moral dimensions of their work, we can better prepare nurses for the challenges they face, ultimately promoting their well-being, decreasing turnover, and sustaining the delivery of compassionate and effective patient care.

CONCLUSION

Moral distress is a significant issue in today’s healthcare system - an issue that has only been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The experiences of the brave nurses in this study illuminate the complex interplay of emotional, ethical, and professional challenges that nurses face daily. The recognition of MD as a pervasive aspect of the nursing profession underscores the critical need for support mechanisms and enhanced educational strategies. As nurses navigate intricate ethical and professional dilemmas, it is crucial to foster a culture that acknowledges, validates, and addresses the emotional toll of their work – both at an educational level and at a professional level. The study emphasizes the need for a supportive work environment and positive team dynamics, providing essential resources to empower nurses in facing challenges with security. Acknowledging systemic factors like adequate compensation and staffing levels is vital for alleviating MD, establishing a foundation for sustained resilience, and enabling nurses to deliver quality care effectively. The findings underscore that cultivating resilience within the nursing workforce not only benefits practitioners’ well-being but also directly contributes to the overall quality of patient care, emphasizing the integral role of a supportive culture in the success of the healthcare system.

REFERENCES

- Association AN. Code of ethics for nurses: With interpretive statements. 2015.

- Corley MC. Nurse moral distress: a proposed theory and research agenda. Nurs Ethics. 2002; 9: 636-650. doi: 10.1191/0969733002ne557oa. PMID: 12450000.

- Oh Y, Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: a quantitative literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2015; 22: 15-31. doi: 10.1177/0969733013502803. Epub 2013 Oct 3. PMID: 24091351.

- Riedel PL, Kreh A, Kulcar V, Lieber A, Juen B. A Scoping Review of Moral Stressors, Moral Distress and Moral Injury in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19: 1666. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031666. PMID: 35162689; PMCID: PMC8835282.

- Leslie Curry, Marcella Nunez-Smith. Mixed Methods in Health Sciences Research: A Practical Primer. SAGE Publications, Inc. 2014.

- Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10- item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007; 20: 1019-1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. PMID: 18157881.

- Keebler JR, Dietz AS, Lazzara EH, Benishek LE, Almeida SA, Toor PA, et al. Validation of a teamwork perceptions measure to increase patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014; 23: 718-726. doi: 10.1136/ bmjqs-2013-001942. Epub 2014 Mar 20. PMID: 24652512.

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 2012.

- Ross A, VL Willson. Independent Samples T-Test. Basic and Advanced Statistical Tests. 2017; 13-16.

- Andrew F Hayes. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. 2013.

- Berry WD. Understanding regression assumptions. Sage. 13edt. 2009.

- Braun V, V Clarke. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006; 3(2): 77-101.

- Bihu R. Qualitative Data Analysis: Novelty in Deductive and Inductive Coding. Advance. 2023.

- John W Creswell, Vicki L Piano Clark. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications. 273.

- Johnson PO, LC Fay. The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika. 1950; 15(4): 349-367.

- Mudallal RH, Othman WM, Al Hassan NF. Nurses’ Burnout: The Influence of Leader Empowering Behaviors, Work Conditions, and Demographic Traits. Inquiry. 2017; 54: 46958017724944. doi: 10.1177/0046958017724944. PMID: 28844166; PMCID: PMC5798741.

- Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35: 422-429. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254722.50608.2D. PMID: 17205001.

- Silverman HJ, Kheirbek RE, Moscou-Jackson G, Day J. Moral distress in nurses caring for patients with Covid-19. Nurs Ethics. 2021; 28: 1137-1164. doi: 10.1177/09697330211003217. Epub 2021 Apr 29. PMID: 33910406.

- Jennifer Hancock, Tobias Witter, Scott Comber, Patricia Daley, Kim Thompson, Stewart Candow, et al. Understanding burnout and moral distress to build resilience: a qualitative study of an interprofessional intensive care unit team. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie. 2020; 67: 1541-1548.

- Rushton CH, Caldwell M, Kurtz M. CE: Moral Distress: A Catalyst in Building Moral Resilience. Am J Nurs. 2016; 116: 40-49. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000484933.40476.5b. PMID: 27294668.

- Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics. 2009; 20: 330-342. PMID: 20120853.

- Squires A, Clark-Cutaia M, Henderson MD, Arneson G, Resnik P. “Should I stay or should I go?” Nurses’ perspectives about working during the Covid-19 pandemic’s first wave in the United States: A summative content analysis combined with topic modeling. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022; 131: 104256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104256. Epub 2022 Apr 20. PMID: 35544991; PMCID: PMC9020864.

- Sullivan CE, King AR, Holdiness J, Durrell J, Roberts KK, Spencer C, Roberts J, et al. Reducing Compassion Fatigue in Inpatient Pediatric Oncology Nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2019; 46: 338-347. doi: 10.1188/19.ONF.338-347. PMID: 31007264.

- Wei H, Aucoin J, Kuntapay GR, Justice A, Jones A, Zhang C, et al. The prevalence of nurse burnout and its association with telomere length pre and during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2022; 17: e0263603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263603. PMID: 35294438; PMCID: PMC8926201.

- Wendell Waters. A Quantitative Study of Relationships Between Compassion Fatigue and Burnout to Turnover Intention in Alabama Trauma Center Nurses. Liberty University. 2021,

- Chloe Olivia Rose Littzen. Young Adult Nurse Work-Related Well- Being, Contemporary Practice Worldview, Resilience, and Co-worker Support during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The University of Arizona: Ann Arbor. 2021; 160.

- Mauro LB. Exploring Moral Distress, Ethical Climate, and Psychological Empowerment among New Registered Nurses. Walden University: Ann Arbor. 2022; 221.

- Maytum JC, Heiman MB, Garwick AW. Compassion fatigue and burnout in nurses who work with children with chronic conditions and their families. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004; 18: 171-179. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2003.12.005. PMID: 15224041.

- Mealer M, Jones J, Newman J, McFann KK, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: results of a national survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012; 49: 292-299. doi: 10.1016/j. ijnurstu.2011.09.015. Epub 2011 Oct 5. PMID: 21974793; PMCID: PMC3276701.

- Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and Resilience Among Nurses Practicing in High-Intensity Settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015; 24: 412-420. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015291. PMID: 26330434.

- Hart PL, Brannan JD, De Chesnay M. Resilience in nurses: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2014; 22: 720-734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365- 2834.2012.01485.x. Epub 2012 Nov 2. PMID: 25208943.

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002; 288: 1987-1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. PMID: 12387650.

- McAndrew NS, Leske JS, Garcia A. Influence of moral distress on the professional practice environment during prognostic conflict in critical care. J Trauma Nurs. 2011; 18: 221-230. doi: 10.1097/ JTN.0b013e31823a4a12. PMID: 22157530.

- Ulrich CM, Taylor C, Soeken K, O’Donnell P, Farrar A, Danis M, et al . Everyday ethics: ethical issues and stress in nursing practice. J Adv Nurs. 2010; 66: 2510-2519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05425.x. Epub 2010 Aug 23. PMID: 20735502; PMCID: PMC3865804.