Optimizing Nitrogen-Zinc Fertilization Enhances Maize Productivity and Soil Nutrients in Semiarid Calcareous Soils

- 1. Key Laboratory of Mountain Surface Processes and Ecological Regulation, Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, China

- 2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, PR China

- 3. Department of Soil and Environmental Science, The University of Agriculture Peshawar, Pakistan

- 4. College of Ecology and Environment, Hainan University Haikou, China

Abstract

Deficiencies of nitrogen (N) and zinc (Zn) significantly limit maize productivity in alkaline calcareous soils of arid and semi-arid regions, despite the well-established importance of balanced macro- and micronutrient management for optimal crop yields. To address this problem, we tested three N levels (100, 150, 200 kg ha-¹) in different combinations with three Zn levels (0, 10, 15 kg ha-¹), including a control (no fertilization), in a field trial on maize at the Swabi Agricultural Research Station, Pakistan. The growth and yield attributes, plant/soil nutrients, and soil properties were assessed under different N-Zn combinations. The optimal combination of N-Zn (N150 +Zn15 ) significantly enhanced cob weight (+127%), 1000-grain weight (+11%), and grain yield (+168%), while elevating plant N (+273%) and Zn (+202%) concentrations, compared to control. The significant increases in soil N (1.76 g kg-¹), Zn (1.56 mg kg-¹), and organic matter (OM; 9.3 g kg-¹) under the same fertilization regime further confirm its efficacy in improving soil health. Additionally, redundancy analysis linked soil OM, Zn, and plant N to yield gains, while random forest regression (R² = 0.93) identified plant N (%IncMSE = 18.98) and soil N (%IncMSE = 14.57) as the top two grain yield productivity predictors. These results demonstrate that the combined application of N150 +Zn15 is an optimal fertilization strategy for balancing yield and soil health in calcareous soils. Future research should focus on long-term field trials across diverse climates and soil types to validate these f indings and develop site-specific fertilizer recommendations for sustainable maize production in similar agroecosystems.

Keywords

• Nitrogen Fertilization

• Maize Productivity

• Nutrient Synergy

• Sustainable Crop Production

• Zinc

Citation

Iqbal J, Ali W, Wahid A, Yao Z (2025) Optimizing Nitrogen-Zinc Fertilization Enhances Maize Productivity and Soil Nutrients in Semiarid Calcareous Soils. JSM Invitro Fertil 5(1): 1030.

INTRODUCTION

Maize (Zea mays L.) ranks among the world’s most crucial cereal crops, serving multiple purposes from food security to industrial applications [1]. As global population growth drives increasing demand for maize production, optimizing crop yields becomes imperative, particularly in regions with nutrient-deficient soils. Among essential nutrients, zinc (Zn) and nitrogen (N) are frequently limiting factors for maize productivity yet their optimal management remains challenging [2,3]. Zn facilitates vital processes including enzyme activation, membrane stability, and photosynthetic efficiency, while N is fundamental for nucleotide formation, protein synthesis, and chlorophyll production, making both nutrients critical for plant growth and development. Maize cultivation in arid and semiarid regions typically occurs in alkaline calcareous soils with minimal organic matter (OM), creating specific nutrient management challenges [4]. In these conditions, high calcium carbonate content and elevated pH significantly reduce Zn bioavailability through mechanisms including precipitation and adsorption to soil particles. Simultaneously, N management is complicated by significant losses through ammonia volatilization, denitrification, and leaching, further exacerbating nutrient deficiencies [5]. Past research has demonstrated complex crop responses to Zn and N applications across different agricultural systems. N influences numerous crop eco physiological processes, with both deficiency and excess significantly impacting maize development [2-6]. Excess N application can reduce nitrogen use efficiency and contribute to groundwater contamination through nitrate leaching [7]. Similarly, while Zn fertilization has shown significant improvements in maize grain production in zinc-deficient soils [8-10], inadequate Zn can reduce pollen viability and result in poor kernel counts [11]. In contrast, some studies reported that Zn fertilizer application to rain fed calcareous soil did not increase maize biomass or grain yields [12]. These contrasting findings highlight the need to identify optimal combinations of N and Zn inputs that maximize yield while minimizing environmental impacts, particularly in challenging soil conditions. Agricultural lands in the present study region are predominantly characterized by calcareous and alkaline soils with low organic matter content, resulting in suboptimal maize production compared to global standards [13]. This study addresses this challenge by systematically evaluating how synergistic N-Zn fertilization can optimize maize yield while mitigating soil constraints in these vulnerable agroecosystems. We aim to: (1) quantify the effects of N and Zn co-application on maize growth and yield attributes; (2) identify soil-plant nutrient dynamics driving productivity gains; and (3) determine environmentally sustainable N-Zn application rates that balance agronomic efficacy with soil health. We hypothesize that combined N-Zn fertilization at optimal rates will enhance maize yield through improved nutrient uptake, metabolic efficiency, and reduced fixation of both nutrients in calcareous soils. The findings provide actionable insights for developing region-specific fertilization strategies in similar agroecological zones, addressing the critical global challenge of enhancing food security while maintaining environmental sustainability in vulnerable agricultural systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental site description and research design

A single-season field trial was conducted from May to September 2015 at the Swabi Agricultural Research Station (34°1′2″N, 71°28′5″E), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The site features a subtropical semi-arid climate (mean annual temperature: 30°C; precipitation: 360 mm) and lies on recent alluvial sediments with dominant soils classified as Fluventic Ustochrepts (USDA) / Eutric Fluvisols (FAO WRB), previously under seasonal vegetable cultivation. The experiment employed a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with three replications. The size of each experimental plot was 3 × 4 m (12 m²). Prior to sowing, four composite soil samples were collected from the topsoil (0–20 cm) to assess initial physicochemical properties (Table 1).

Table 1: Basic physicochemical properties of pre-experimental soil.

|

Property |

Unit |

Value |

|

Sand |

% |

25.2 |

|

Clay |

% |

63.7 |

|

Silt |

% |

11.1 |

|

Textural Class |

--------- |

Silty Loam |

|

pH |

--------- |

7.72 |

|

Organic matter |

% |

0.23 |

|

CaCO3 |

% |

13.6 |

|

Zn |

mg kg-1 |

0.39 |

|

N |

% |

0.09 |

The maize hybrid “Pioneer 3025” was sown at 30 kg ha?¹ on flat beds with 75 cm row spacing and 25 cm plant spacing. The experiment consisted of ten treatments: a control (no fertilization) and nine treatments combining three N levels (100, 150, 200 kg ha?¹ as urea) with three Zn levels (0, 10, 15 kg ha?¹ as ZnSO4 ), as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Description of the different treatments used in the study.

|

Treatment |

Fertilizer |

Abbreviation |

|

T1 |

Control (no fertilizer) |

Control |

|

T2 |

100 kg/ha nitrogen + 0 kg/ha zinc |

N100 + Zn0 |

|

T3 |

100 kg/ha nitrogen + 10 kg/ha zinc |

N100 + Zn10 |

|

T4 |

100 kg/ha nitrogen + 15 kg/ha zinc |

N100 + Zn15 |

|

T5 |

150 kg/ha nitrogen + 0 kg/ha zinc |

N150 + Zn0 |

|

T6 |

150 kg/ha nitrogen + 10 kg/ha zinc |

N150 + Zn10 |

|

T7 |

150 kg/ha nitrogen + 15 kg/ha zinc |

N150 + Zn15 |

|

T8 |

200 kg/ha nitrogen + 0 kg/ha zinc |

N200 + Zn0 |

|

T9 |

200 kg/ha nitrogen + 10 kg/ha zinc |

N200 + Zn10 |

|

T10 |

200 kg/ha nitrogen + 15 kg/ha zinc |

N200 + Zn15 |

All plots received uniform basal applications of phosphorus (90 kg ha?¹ as single superphosphate, SSP) and potassium (60 kg ha?¹ as sulfate of potash, SOP). Standard agronomic practices (tillage, pest/weed control) were maintained uniformly across plots. Irrigation was supplied via canal water at 50–60 mm weekly, aligned with crop requirements.

Plant growth and yield assessment

At crop maturity (early September 2015), ten plants were randomly selected from the middle two rows of each plot to minimize edge effects. Plant height was measured from the first nodal mark (base) to the base of the tassel (topmost forked leaf) using a meter rule, with mean values calculated per plot. The number of plants per plot was determined by manual counts of all plants within each treated plot. For yield components, ten additional plants were harvested from the central rows. Cobs were manually harvested from plants, counted, and oven-dried at 65°C (48–72 h) until constant weight was achieved. Grain yield (kg ha?¹), cob weight (kg ha?¹), and 1000-grain weight (g) were quantified from manually threshed and dried grains.

Plant tissue and soil nutrient analysis

At maturity, four ear leaves (nearest to the primary cob) were collected per plot for N and Zn analysis. Leaves were oven-dried (65°C, 48–72 h), ground to a fine powder (<0.5 mm sieve), and stored in airtight containers. Additionally, post-harvest, one composite soil sample from each plot (0 20 cm depth) was collected using a stainless-steel auger. Samples were air-dried (5–7 days), sieved (<2 mm), and analyzed for pH, electrical conductivity (EC), soil OM, N and Zn concentrations determinations at the University of Agriculture, Peshawar. The pH of the soil was measured using an HI 9017 microprocessor pH meter in a soil and distilled-water (1:2.5 m/v) suspension once equilibrated for about an hour. To determine soil OM, Walkley and Black method was used [14]. Briefly, 1g air-dried samples were treated with 20 mL concentrated H?SO? and 10 mL of 0.167 N K?Cr?O?, and then left for about 30 minutes to proceed the reaction. For excess dichromate titration, 0.5 N FeSO? was used before measuring OM content. For EC analysis, 10 g soil was mixed with 25ml deionized water (1:2.5 m/v) to make suspension which was equilibrated for 30 minutes before measuring EC with a pre-calibrated EC meter [15]. N contents in both soil and plant were measured by Kjeldahl digestion method [16]. Briefly, 0.5g of plant and 1g of soil’s finely-ground samples were digested with concentrated H?SO? before distillation to capture NH3 in a boric acid solution. Standard HCL was used to titrate NH3 , and then N contents in both soil and plant samples were measured based on the volume of HCL required for neutralization. Additionally, Zn concentrations in both soil and plant samples were determined via atomic absorption spectrophotometry method [17]. Briefly, 0.5g of finely grounded soil and plant samples were first digested with a mixture of HNO? and HClO4 . The solutions were filtered, diluted, and then analyzed for Zn concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Prior to analysis, data normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk (p > 0.05) and Levene’s tests (p > 0.05), respectively. When assumptions were met, significant differences among treatments were evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post hoc test (p < 0.05) in OriginPro 2024 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). Pearson correlation and redundancy analysis (RDA) were performed in OriginPro 2024 on Z-score standardized data to assess variable relationships and multivariate drivers of yield. To quantify variable importance, random forest regression (1000 permutations) was implemented via the rfPermute package in R (v4.3.1; R Core Team, 2023), with permutation-based significance testing for %IncMSE values [18].

RESULTS

Growth and yield attributes under different fertilization

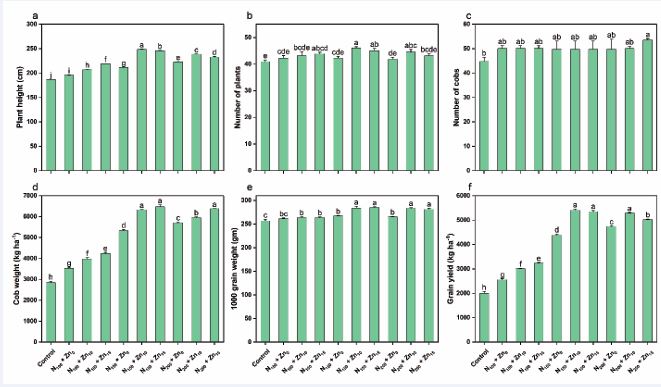

All fertilization treatments significantly influenced growth and yield parameters of maize crop. The N150 + Zn10 treatment produced the tallest plants (248.1 cm), a 33% increase over the control (186.6 cm; Figure 1a), and the highest number of plants (46.1; Figure 1b). Cob numbers peaked under N200 + Zn15 (53), while the control yielded the lowest (44; Figure 1c). Cob weight reached its maximum (6467 kg ha?¹) under N150 + Zn15 , with no significant difference observed between N150 + Zn10 , and N200 + Zn15 (Fig. 1d). Similarly, the highest 1000-grain weight (285.3 g) was recorded in N150 +Zn15 , statistically comparable to N150 + Zn10 , N200 + Zn10 , and N200 + Zn15 (Figure 1e). Optimal grain yield (5406 kg ha?¹) was achieved with N150 + Zn10 , showing no significant difference from N200 + Zn10 and N150 + Zn15 , while the control yielded only 1994 kg ha?¹ (Figure 1f).

Figure 1 Plant height, number of plants, number of cobs, cob weight, 1000-grain weight and grain yield under different treatments. The lowercase letters positioned on top of bars shows significant differences among treatments at the level of p < 0.05, while the error bars indicate standard error (n=3).

Plant and soil nutrients under different fertilization

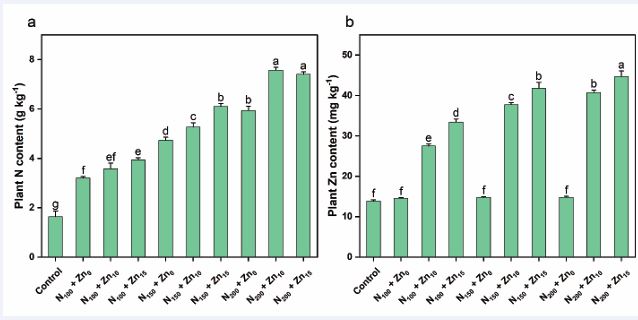

Plant N and Zn concentrations varied significantly across fertilization treatments (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Nitrogen (N) and zinc (Zn) concentrations in plant under different treatments. The lowercase letter on top of bars denotes significant differences between the treatments (p < 0.05), while error bars represent standard error (n=3).

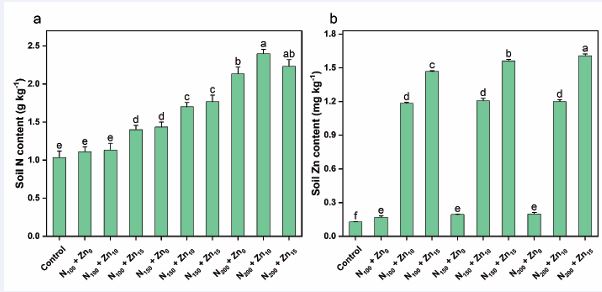

The highest N concentration (7.56 g kg?¹) was obtained in the N200 + Zn10 treatment, statistically similar to N200 + Zn15 , while the control yielded the lowest (Figure 2a). Plant Zn peaked at 44.7 mg kg?¹ under N200 + Zn15 , contrasting sharply with the lowest values observed in treatments without Zn fertilization (Figure 2b). Moreover, total soil N and Zn content differed significantly across fertilization treatments (Figure 3). The highest soil N (2.4 g kg?¹) was recorded under N200 + Zn10, statistically similar to N200 + Zn15 , while the control exhibited the lowest value (1.03 g kg?¹; Figure 3a). Soil Zn concentrations peaked at 1.61 mg kg?¹ under N200 + Zn15 , contrasting with the minimum value (0.13 mg kg?¹) in the control. Treatments without Zn fertilization consistently exhibited the lowest soil Zn levels compared to Zn-amended treatments (Figure 3b).

Figure 3 Soil nitrogen (N) and zinc (Zn) concentrations under different treatments. The lowercase letters on top of bars indicates significant differences among the treatments (p < 0.05), while the error bars denote standard errors (n = 3).

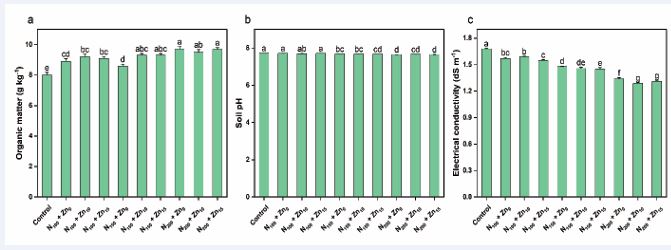

Post-harvest soil properties

Post-harvest soil properties varied significantly across fertilization treatments. OM increased markedly, with the highest concentration (9.74 g kg?¹) observed under N200 + Zn15 , statistically comparable to N200 + Zn10 and N200 + Zn0 , compared to the lowest OM (8.01 g kg?¹) recorded under control (Figure 4a). Soil pH also varied across treatments, peaking at 7.72 in the control and declining to 7.65 under N200 + Zn15 (Figure 4b). EC also differed significantly, with the lowest EC (1.29 dS m?¹) in N200 + Zn10 , showing no statistical difference from N200 + Zn15 , compared to the highest EC (1.68 dS m?¹) in the control (Figure 4c).

Figure 4 Organic matter, soil pH and electrical conductivity under different treatments. The lowercase letters on top of bars indicates significant differences among the treatments (p < 0.05), while the error bars denote standard errors (n = 3).

Drivers of Yield Attributes:

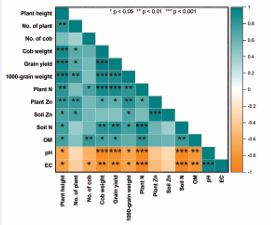

Nutrient Dynamics and Soil Interactions Growth and yield attributes exhibited strong positive correlations with soil and plant nutrient concentrations (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Correlogram showing associations among growth and yield parameters (plant height, number of plants, number of cobs, cob weight, grain yield, and 1000-grain weight), plant and soil nutrients (plant N, plant Zn, soil N and soil Zn), and post-harvest soil properties (organic matter; OM, pH, and electrical conductivity; EC). Positive correlations are displayed in dark cyan, while negative correlations are shown in orange, with color intensity scaled according to the magnitude of the correlation coefficients

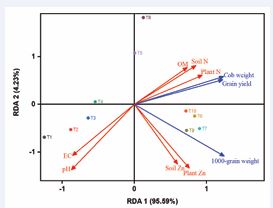

Conversely, EC and pH displayed negative correlations with these parameters under all fertilization regimes. Redundancy analysis (RDA) corroborated these relationships, with soil OM, soil Zn, and plant N strongly associated with cob weight and grain yield under high N + Zn fertilization (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Redundancy analysis (RDA) depicting the influences of pH, electrical conductivity (EC), organic matter (OM), soil and plant N concentrations, and soil and Plant Zn concentrations (red arrows; explanatory variables) on the yield attributes of maize (blue arrows; response variables) under different treatments. The length of each arrow indicates the strength of the variable’s contribution to the ordination axes; i.e. longer arrows represent stronger influences. The angles between arrows reflect correlations: small angles indicate a strong positive association, angles near 90° suggest little to no correlation, and angles approaching 180° indicate a negative relationship.

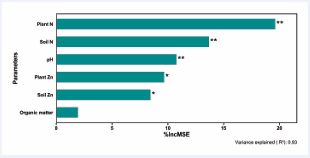

Lower N fertilization rates increased soil pH and EC. The first two RDA axes collectively explained 99.8% of the variance (Axis 1: 95.6%; Axis 2: 4.2%). Additionally, random forest regression (R² = 0.93) identified plant N (%IncMSE = 18.98, p = 0.002), soil N (%IncMSE = 14.57, p = 0.002), and pH (%IncMSE = 11.51, p = 0.006) as the strongest predictors of grain yield. Plant Zn and Soil Zn showed moderate effects (p < 0.05), while OM had no significant influence (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Variable importance from Random Forest regression analysis showing the relative influence of soil and plant nutrients, organic matter (OM), and soil pH on grain yield. Significance levels based on %IncMSE permutation importance are denoted by asterisks positioned to the right of bars (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Growth and yield attributes under different fertilization

The synergistic application of N and Zn significantly enhanced maize growth and yield by improving soil-plant nutrient availability. Plant height and the number of plants, key determinants of yield, increased markedly under N-Zn fertilization, likely due to Zn’s role in auxin-mediated cell elongation [19]. and N’s critical function in vegetative biomass accumulation [20]. Optimal Zn levels mitigated growth inhibition caused by Zn deficiency or toxicity, while N ensured robust photosynthetic activity and carbohydrate breakdown to reproductive organs [10]. These interactions amplified cob weight and 1000-grain weight, consistent with Zn’s role in phloem-mobile carbohydrate synthesis [21]. and N’s contribution to starch formation [8]. Notably, the substantial increase of grain yield emphasized the vital role of N in yield optimization [22], and Zn’s global efficacy in closing yield gaps [23]. Our findings align with studies linking Zn-N synergies to kernel development and cob sink capacity [24,25]. demonstrating that calibrated fertilization directly addresses physiological constraints in calcareous soils.

Plant and soil nutrients under different fertilization The N150 +Zn15 fertilization regime elevated plant N and Zn concentrations, reflecting improved nutrient bioavailability in calcareous soils. Enhanced plant N uptake, a critical yield predictor [3]. likely arose from N’s mobility in soil solution, even under alkaline conditions [26]. Similarly, ZnSO4 application countered calcareous soil constraints (e.g., Zn²? fixation via CaCO? adsorption) by increasing soluble Zn²? and chelated Zn availability [27,28]. The notable increases in the soil Zn levels under high Zn application is suggesting that N-induced rhizosphere acidification (via NH4 ? nitrification) enhanced Zn solubility [12]. This aligns with studies showing N-Zn co-application improves Zn Phyto availability in alkaline soils [10-30]. Furthermore, microbial activity surged under higher fertilization rates, accelerating OM mineralization and nutrient cycling [31]. This created a positive feedback loop: enriched soil N/Zn pools sustained plant uptake, while root exudates and residue return further supported microbial biomass and OM accrual.

Post-harvest soil properties Fertilization altered key soil health indicators, with higher amounts of N and Zn applications reducing pH and EC while increasing soil OM. The pH decline stemmed from H? release during NH4 ? nitrification [32], a process amplified by higher N fertilization [33]. Conversely, the significant increase in soil OM accumulation likely originated from elevated crop residue inputs and microbial decomposition of root exudates [34]. Organic acids from residue breakdown further moderated pH and stimulated microbial activity, enhancing nutrient mineralization. Notably, Zn application had no substantial effects on pH and EC [35], stressing N’s role as the primary driver of soil pH and EC dynamics. However, Zn’s indirect contribution to soil OM via biomass production highlights its integrative role in soil fertility. These dynamics underscore the necessity of balanced N-Zn fertilization: excessive N elevates acidification risks, while optimal Zn sustains yield-driven organic matter accrual. Our findings demonstrate that combined N and Zn fertilization at optimal rates boosts maize yield and enhances soil health. However, spatiotemporal variability in soil health indices [36,37], highlights the need for long-term and/or multi-region trials to validate the sustainability of these fertilization regimes.

CONCLUSIONS

Our results revealed that the optimal N and Zn fertilization regime (N150 + Zn15 ) maximized maize yield (+168% vs. control), and soil nutrient retention in calcareous semi-arid soils. This finding was further validated by multivariate analyses, with RDA showing soil OM, Zn, and plant N explaining 99.8% of yield variance, while random forest modeling identified plant N (%IncMSE = 18.98) and soil N (%IncMSE = 14.57) as the strongest yield predictors (R² = 0.93). The N150 + Zn15 treatment achieved optimal balance between resource input and yield output, preventing excess fertilization while maintaining productivity. We therefore recommend 15 kg Zn ha?¹ + 150 kg N ha?¹ for maize in similar agroecological zones. Future research is suggested to clarify N-Zn synergistic mechanisms under variable climate conditions and soil types to develop site-specific, economically viable fertilization strategies for sustainable maize production in alkaline environments.

STATEMENTS AND DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgement

We are highly thankful to the Swabi Agricultural Research Centre, KPK, Pakistan for using their resources during this entire study and also to The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan for their support and allowing to use lab facilities throughout this study.

Availability of data and material

The data is available from corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Chekole FC, Mohammed Ahmed A. Future climate implication on maize (Zea mays) productivity with adaptive options at Harbu district, Ethiopia. J Agric Food. 2023; 11: 100480.

- Mueller SM, Vyn TJ. Physiological constraints to realizing maize grain yield recovery with silking-stage nitrogen fertilizer applications. Field Crops Res. 2018; 228: 102-109.

- Guo J, Fan J, Xiang Y, Zhang F, Yan S, Zhang X, et al. Maize leaf functional responses to blending urea and slow-release nitrogen fertilizer under various drip irrigation regimes. Agric Water Manag. 2022; 262: 107396.

- Xing F, Fu X, Wang N, Xi J, Huang Y, Zhou W, et al. Physiological changes and expression characteristics of ZIP family genes under zinc deficiency in navel orange (Citrus sinensis). J Integr Agric. 2016; 15: 803-811.

- Saboor A, Ali MA, Hussain Shabir, El Enshasy HA, Hussain Sajjad, Ahmed N, et al. Zinc nutrition and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis effects on maize (Zea mays L.) growth and productivity. Saudi J Biol Sci. 28: 6339-6351.

- Ma Q, Wang M, Zheng G, Yao Y, Tao R, Zhu M, et al. Twice-split application of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer met the nitrogen demand of winter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2021; 267: 108163.

- Shen Y, Sui P, Huang J, Wang D, Whalen JK, Chen Y. Global warming potential from maize and maize-soybean as affected by nitrogen fertilizer and cropping practices in the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2018; 225: 117-127.

- Potarzycki J, Grzebisz W. Effect of zinc foliar application on grain yield of maize and its yielding component. Plant Soil Environ. 2009; 55: 519-527.

- Zhang YQ, Pang LL, Yan P, Liu DY, Zhang W, Yost R, et al. Zinc fertilizer placement affects zinc content in maize plant. Plant Soil. 2013; 372: 81-92.

- Liu DY, Zhang W, Yan P, Chen XP, Zhang FS, Zou CQ. Soil application of zinc fertilizer could achieve high yield and high grain zinc concentration in maize. Plant Soil. 2017; 411: 47-55.

- Liu DY, Zhang W, Liu YM, Chen XP, Zou CQ. Soil Application of Zinc Fertilizer Increases Maize Yield by Enhancing the Kernel Number and Kernel Weight of Inferior Grains. Front Plant Sci. 2020; 11: 188.

- Wang J, Mao H, Zhao H, Huang D, Wang Z. Different increases in maize and wheat grain zinc concentrations caused by soil and foliar applications of zinc in Loess Plateau, China. Field Crops Res. 2012; 135: 89-96.

- Shahab Q, Afzal M, Hussain B, Abbas N, Hussain S, Zehra Q, et al. Effect of different methods of zinc application on maize (Zea mays L.). 2016.

- Walkley A, Black IA. An examination of the degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934; 37: 29.

- Rhoades JD. Salinity: Electrical Conductivity and Total Dissolved Solids. In: Methods Soil Anal. 1996; 417-435.

- Bremner JM. Nitrogen-Total. In: Methods Soil Anal John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1996; 1085-1121.

- Wright RJ, Stuczynski T. Atomic Absorption and Flame Emission Spectrometry. In: Methods Soil Anal. 1996; 65-90.

- Archer E. rfPermute: Estimate Permutation p-Values for Random Forest Importance Metrics. R package. 2022.

- Zhang L, Yan M, Li H, Ren Y, Siddique KH, Chen Y, et al. Effects of zinc fertilizer on maize yield and water-use efficiency under different soil water conditions. Field Crops Res. 2020; 248: 107718.

- Singh J, Partap R, Singh A, Kumar N, Krity. Effect of Nitrogen and Zinc on Growth and Yield of Maize (Zea mays L.). 2021; 12.

- Rengel Z. Genotypic Differences in Micronutrient Use Efficiency in Crops. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2001; 32: 1163-1186.

- Biswas DK, Ma BL. Effect of nitrogen rate and fertilizer nitrogen source on physiology, yield, grain quality, and nitrogen use efficiency in corn. Can J Plant Sci. 2016; 96: 392-403.

- Hossain MA, Jahiruddin M, Islam MR, Mian MH. The requirement of zinc for improvement of crop yield and mineral nutrition in the maize-mungbean-rice system. Plant Soil. 2008; 306: 13-22.

- Imran S, Arif M, Khan A. Effect of Nitrogen Levels and Plant Population on Yield and Yield Components of Maize. Adv Crop Sci Technol. 2015; 3: 170.

- Dampare F, Danso I, Ofosu-Budu KG. IMPACT OF ZINC AND NITROGEN FERTILIZER ON THE GROWTH AND YIELD OF MAIZE IN THE SEMI-DECIDUOUS FOREST ZONE OF GHANA. J Ghana Sci Assoc. 2020; 19: 24-29.

- Mondal S, Kumar R, Mishra JS, Dass A, Kumar S, Vijay KV, et al. Grain nitrogen content and productivity of rice and maize under variable doses of fertilizer nitrogen. Heliyon. 2023; 9: e17321.

- Cakmak I. Enrichment of cereal grains with zinc: Agronomic or genetic biofortification? Plant Soil. 2008; 302: 1-17.

- Mutambu D, Kihara J, Mucheru-Muna M, Bolo P, Kinyua M. Maize grain yield and grain zinc concentration response to zinc fertilization: A meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023; 9: e16040.

- Tariq M, Khan MA, Perveen S. Response of Maize to Applied Soil Zinc. Asian J Plant Sci. 2002; 1: 476-477.

- Shafea L, Saffari M. Effects of zinc (ZnSO4) and nitrogen on chemical composition of maize grain. Int J AgriScience. 2011; 1: 323-328.

- Widdig M, Heintz-Buschart A, Schleuss P-M, Guhr A, Borer ET, Seabloom EW, et al. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus addition on microbial community composition and element cycling in a grassland soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2020; 151: 108041.

- Wang J, Tu X, Zhang H, Cui J, Ni K, Chen J, et al. Effects of ammonium- based nitrogen addition on soil nitrification and nitrogen gas emissions depend on fertilizer-induced changes in pH in a tea plantation soil. Sci Total Environ. 2020; 747: 141340.

- Guo JH, Liu XJ, Zhang Y, Shen JL, Han WX, Zhang WF, et al. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science. 2010; 327: 1008-1010.

- Dawar K, Ali W, Bibi H, Mian IA, Ahmad MA, Hussain MB, et al. Effect of Different Levels of Zinc and Compost on Yield and Yield Components of Wheat. Agronomy. 2022; 12: 1562.

- Kumar S, Verma G, Dhaliwal S. Zinc Phasing and Fertilization Effects on Soil Properties and Some Agromorphological Parameters in Maize–Wheat Cropping System. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2022; 53: 453-462.

- Zhou J, Tang S, Pan W, Xu M, Liu X, Ni L, et al. Long-term application of controlled-release fertilizer enhances rice production and soil quality under non-flooded plastic film mulching cultivation conditions. Agric Ecosyst Environ.2023; 358: 108720.

- Li G, Zhao B, Dong S, Zhang J, Liu P, Lu W. Controlled-release urea combining with optimal irrigation improved grain yield, nitrogen uptake, and growth of maize. Agric Water Manag. 2020; 227: 105834.