Peripheral Neural Regulation of Pregnancy Corpus Luteum

- 1. Laboratorio de Biología de la Reproducción (LABIR), Laboratorio de Biología de la Reproducción (LABIR), Argentina

Abstract

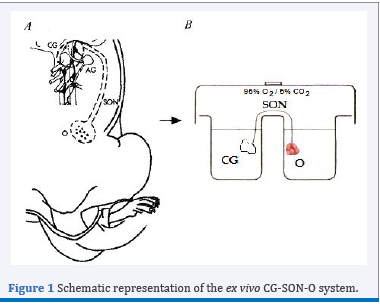

The corpus luteum (CL) is an ovarian endocrine gland with limited functional life. The importance of this structure lies in the fact that its main product, progesterone, is essential for the maintenance of pregnancy. As result, mammals have developed a complex series of regulatory mechanisms to support its synthesis and secretion at appropriate levels through gestation. Peripheral innervation represents an additional regulatory mechanism to the classical endocrine. This has been studied through the use of ex vivo coeliac ganglion-superior ovarian nerve-ovary integrated system (CG-SON-O), which was incubated in buffer solution until 240 min, with the CG and the ovary located in different compartments and linked by the SON. This review focuses on the stimulus of different neural and hormonal agents on the CL of pregnancy through the CGSON-O system in the rat.

Keywords

• Corpus luteum

• Luteal regression

• Coeliac ganglion

• Pregnancy

CITATION

Vallcaneras S, Casais M (2017) Peripheral Neural Regulation of Pregnancy Corpus Luteum. JSM Invitro Fertil 2(3): 1021.

ABBREVIATIONS

CL: Corpus Luteum; CG-SON-O: Coeliac Ganglion-Superior Ovarian Nerve-Ovary; NA: Noradrenaline; A2 : Androstenedione; E2 : Oestradiol; 3β-HSD: 3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase; 20α-HSD: 20α-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase; NO: Nitric Oxide; PGF2α: Prostaglandin F2α

INTRODUCTION

The corpus luteum (CL) is the ovarian structure whose full functionality is essential during the 22 days of pregnancy in the rat, unlike human that is only in the first trimester. Its function is the secretion of progesterone, fundamental hormone for the successful implantation and maintenance of pregnancy. At the end of its useful life, this ephemeral tissue suffers a process of functional and structural regression until its complete disappearance from the ovary. Although this critical process for reproductive function has been extensively studied, many of the regulatory mechanisms involved are poorly understood.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the ex vivo CG-SON-O system.

The neural signals represent additional control of ovarian function in addition to classical endocrine regulation [1]. One of the neural pathways that arrives at the ovary is the Superior Ovarian Nerve (SON), mainly constituted by adrenergic fibres, most of which originate in the coeliac ganglion GC [2]. To study the peripheral neural influence on the ovarian physiology, our laboratory has standardized an integrated ex vivo system known as CG-SON-O [3]. This system is a functional entity which viability has been supported by histological studies at the end of its incubation and it has an own autonomic tone, which allows the use of antagonist without the simultaneous addition of the agonists. This scheme has a singular value for the study of a dynamic gland with complex regulatory mechanisms such as the CL, since it allows preservation of innervations and paracrine and autocrine regulations without the humoral effect. To clarify, a schematic representation of the ex vivo CG-SON-O system may be observed in Figure 1.

The present review summarizes of available evidence of the impact of neural and hormonal agents on the CL of pregnancy through the CG-SON-O system in the rat, focusing on luteal regression.

Action of neural agents on the CL of pregnancy through the CG-SON-O system in the rat

The CG is part of the sympathetic prevertebral chain and it possesses mechanisms that regulate the flow of signals between the gonads and the central nervous system. This ganglion receives fibres of adrenergic nature which come from the medulla and others preaortic ganglia [4,5]. The symphatetic ganglionic neurons have α and β adrenergic receptors [6]. The presence of such receptors was demonstrated physiologically in adult rat during the oestrus cycle and pregnancy [3,7]. Precisely, it was found that in the second half of pregnancy, the addition of noradrenaline (NA) to the ganglionic incubation medium, using the CG-NOS-O system, stimulates the ovarian progesterone release on day 15 and 19. Such effect begins to fall on day 20 and is null at day 21. These data indicate that the steroidogenic response to neural action gradually decreases with the establishment of physiological luteal regression at the end of gestation. The simultaneous addition of LH to the incubation medium ovarian decreases the effect of NA, which reveals an antagonism between the neurotransmitter and the hormone. On the other hand, the presence of isoproterenol, β-adrenergic agonist in culture of isolated luteal cells, obtained from rats at day 15 of gestation, does not modify the release of progesterone [7]. Conversely, a recent study shows that both NA and isoproterenol increased progesterone production through activating β adrenergic receptors in murine cells from luteinized ovaries [8]. It is possible that the different origin of luteal cells may be responsible of disagreement in these results. Taking together the results in our study indicate that the integrity of the system, in which the ovarian and neural structures are preserved, is essential for the ovarian response to neural stimulation. Casais et al. [9], also analyzed the influence of the ganglionic noradrenergic stimulation on the ovarian release of androstenedione (A2 ), hormone with known luteotrophic effect in rat [10-12], and if consequently causes a modification in the antisteroidogenic effect of LH at the end of pregnancy. The study concludes that such stimulus in ganglion reinforces the inhibitory effect induced by LH on ovarian A2 release and that this mechanism of action, in turn, is associated with changes in the release of catecholamines in the ovary. It is possible that in an attempt to favor physiological luteal regression at the end of pregnancy in the rat, the signal coming from the CG may be a fine modulator together LH to limit the production of A2 .

In the sympathetic ganglia, acetylcholine is considered to be the classic preganglion neurotransmitter [13,14] and it possesses nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors in the ganglionic neurons called principal neurons as well as muscarinic receptors in other neuronal populations [15,16]. The stimulation of such receptors causes modifications in the steroids release in cyclic rats [17-19] and prepubertal rats [20].

Regarding the action of cholinergic agents during the pregnancy, stimulus of the CG with acetylcholine on day 15 of gestation decreases the release of ovarian progesterone and A2 . While on days 19, 20 and 21 of pregnancy, although the same effect remains on the release of androgen, no changes on the progesterone release were observed, indicating that the steroidogenic response to neural action gradually decreases with the establishment of physiological luteal regression. Thus, the ganglionic cholinergic action, mainly in relation to the release of A2 , would act favoring the luteal regression necessary for the delivery to occur [21].

Together, these data suggest that the peripheral neural system may act as a modulator of a dynamic structure as is the CL of pregnancy and in conditions that require a mechanism of fine-tuning such as the luteal regression.

Action of hormonal agents on the CL of pregnancy through the CG-SON-O system in the rat

Several studies support the effect of hormonal agents on the peripheral nervous system [22-25]. The sympathetic ganglia have fenestrated capillaries [26]. In addition, different hormone receptors have been demonstrated in ganglionic neurons [23,27- 30]. Thus, hormones or others bioactives substances may arrive to the ganglionic neurons and regulate the flow of signals through microvasculature.

A2 is the principal circulating androgen in the rat and possesses, in the ovary, a well-known luteotrophic action, which occurs by either its intraluteal conversion to estradiol or also by a direct effect [10,30,31].

Casais et al. [9], observed that in the CG-SON-O system extracted from animals on days 19 and 21 of pregnancy, with previous s.c. administration (48 h) of 10 mg A2 /0.2 ml oil vehicle, the levels of progesterone increased significantly in the ovarian compartment. These results support the idea that, in vivo, the humoral environment is highly influential on the functioning of the CG, thus affecting the ovary by a neural pathway. When the direct ganglionic effect of A2 was analysed in the CG-SON-O system, the results were highly surprising. The levels of progesterone in the ovarian compartment obtained by the application of A2 to the CG in relation to the controls were significantly higher. Thus, A2 can reverse the functional regression of the late pregnancy CL when administered systemically or when added directly to the ganglion compartment via SON.

Then, the mechanisms by which A2 exerts luteotrophic effect from CG were further studied by Vallcaneras et al. [28]. The A2 addition in CG increased 3β-HSD and decreased 20α-HSD activities in ovary, enzymes involved in progesterone synthesis and metabolism, respectively [32,33] and it increased ovarian nitric oxide (NO) release, neurotransmitter found in sympathetic ganglia with influence on ovary physiology [34-36]. We further demonstrated by immunohistochemistry cytoplasmatic androgen receptor immunoreactivity in neural somas in the CG and it was provided evidence for the luteotrophic action of A2 via a neural pathway that may be mediated by these receptors with the use of flutamide, an androgen receptor antagonist [37,31].

On day 4 postpartum, the CL of pregnancy is at advanced regression with reduced capacity to synthesize progesterone and high rate of apoptotic cell death [38]. In addition, expression of regulatory factors involved in cell survival and death such as Bcl-2, Bax and the Fas-FasL system have been reported in the CL regression [39-41]. A2 added in CG from rats on day 4 postpartum without lactation increased A2 and E2 release, while at the same time induced a decline in the expression of proapoptotic FasL. These luteotrophic effects caused by the presence of A2 in CG are associated with increased levels of NA and decreased levels of NO in the ovarian compartment. This suggests that the regressing CL of pregnancy present in postpartum ovary maintain certain responsiveness to stimuli of A2 from CG [42].

Other key hormone in regulating reproductive processes is E2 . During mid-pregnancy, E2 is required for luteal survival, while at the end of pregnancy, E2 levels increase in the ovarian vein and in the general circulation [43,44]. It has been proposed that such increase is responsible for increased expression of prostaglandin F2α receptor, luteolityc factor that induce 20α-HSD in association with CL functional regression [45]. Thus, E2 added directly to the ovarian incubation medium decreased progesterone release as well as 3β-HSD expression and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax. While, E2 added to CG of CG-SON-O system also decreased progesterone ovarian release but without modification in luteal expression of progesterone metabolizing enzymes, Bcl-2 and Bax [46]. Anesetti et al. [23], demonstrated the presence of estrogen receptors in CG neurons of prepubertal rats, suggesting that the CG is likely a target of E2 . These results would demonstrate that the indirect luteotrophic action of A2 via the SON is an effect of the androgen per se, not mediated through its previous conversion into E2 . E2 either directly in ovary or indirectly from CG has an antiesteroidogenic effect at the end of pregnancy in the rat and this effect is more pronounced when E2 is directly added in ovary.

There are numerous studies that demonstrate the local survival effect of progesterone on the CL, stimulating its own secretion and protecting the CL from cellular death [33,47]. In addition, progesterone is able to perform luteotrophic effect through neural pathway. Ghersa et al. [29], demonstrated the presence of progesterone receptors in CG neurons and they observed that the progesterone addition in CG of CG-SON-O system increased the ovarian progesterone release and the 3β-HSD activity, whereas decreased the expression and activity of 20α-HSD. In addition, a decrease in the number of apoptotic nuclei and a decrease of the expression of FasL were observed. Progesterone may access the ganglionic neurons, bind to the specific receptors and induce release of neurotransmitters via the SON, which would modulate ovarian function.

It is known that prolactin, besides the known trophic effect on the CL, also has a luteolytic effect depending upon the nature of the CL and of the hormonal environment to which they are exposed. Just before parturition, there is a large secretion of prolactin from the pituitary needed to stimulate lactogenesis and to develop maternal behaviour required immediately after parturition [48- 50]. It has been postulated that circulating prolactin at the end of gestation has a role in the regression of the CL of pregnancy from CG through SON [51]. At the moment, according to the literature available, the presence of receptors for prolactin at the level of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system has not been confirmed. However, there is evidence suggesting that prolactin might act on sympathetic ganglions to affect different aspects of their metabolism [52]. The prolactin addition in CG of CG-SON-O system triggered an inhibitory effect on progesterone ovarian release with an increase in the progesterone catabolising capacity marked by the increase in 20α-HSD expression. We also found that prolactin from CG increased ovarian PGF2α release. These results are in agreement with the fact that in rodents a decline in progesterone levels is essential for luteal regression to occur and this is mediated by 20α-HSD, which is increased by PGF2α at the end of pregnancy [53]. Ganglionic prolactin also increased the levels of NO in the ovarian medium and it diminished the luteal expression of Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic factor) and Bcl-2:Bax ratio, which tilts the balance towards a pro-apoptotic environment [54]. These findings indicate that prolactin may gain access to the CG impacting indirectly on ovarian physiology and inducing the release of PGF2α and NO, which may favour luteal regression at the end of rat pregnancy.

Then, the prolactin effect from CG on the functionality of the ovaries was analyzed on day 4 postpartum in two different endocrine environments: lactating vs. non-lactating animals [55]. Prolactin added in the CG of non-lactating rats increased ovarian progesterone release, which however did not reach the basal levels observed in lactating rats. In addition, prolactin from CG decreased the ratio of Bcl-2:Bax and increased release of ovarian PGF2α, NO and E2 . On the other hand, the ovarian gland in lactating rats is developed in an environment characterized by high levels of prolactin and may be unable to respond to further input of prolactin from the CG mediated via the SON. Goyeneche and Telleria [56] propose that prolactin has different effects on pregnancy CL depending upon the prevailing steroid concentrations. These authors observed in non-lactating postpartum rats receiving subcutaneous E2 that prolactin stimulated luteal apoptosis in the presence of high levels of progesterone. By contrast, during lactation prolactin in presence of high serum levels of progesterone prevents apoptosis in CL and in this physiological situation the E2 levels are low. Thus, our results indicate that prolactin added to the CG via the SON may favor the regression of luteal tissue in non-lactating animals. On the other hand, it is highly possible that in lactating rats the direct prolactin effect prevails over the prolactin effect from CG on the ovaries. Thus, the indirect prolactin effect through peripheral neural pathway may be operational in times of transition when the CL needs to be either abruptly interrupted or rescued from apoptosis

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In conclusion, the evidence from this review indicates that neural or endocrine signals may impact the CL of pregnancy through peripheral nervous system modulating its function. Therefore, these mechanisms may become important in disorders related to inadequate progesterone secretion by the CL that have been implicated as etiologic factors for recurrent pregnancy loss such as luteal phase deficiency, hyperprolactinemia, polycystic ovarian syndrome and psychoemotional stress.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all those who have contributed in the works summarized in the present review.

REFERENCES

12. Telleria CM. Can luteal regression be reversed? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2006; 4: 53.

37. Kemppainen JA, Lane MV, Sar M, Wilson EM. Androgen receptor phosphorylation, turnover, nuclear transport, and transcriptional activation. Specificity for steroids and antihormones. J Biol Chem. 1992; 267: 968-974.