Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock- Human Interaction: A Critical Public Health Issue

- 1. Department of Microbiology, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka-1342, Bangladesh

- 2. Department of Applied Nutrition and Food Technology, Islamic University, Kushtia-7003, Bangladesh

ABSTRACT

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a serious concern to worldwide public health, as it compromises the effectiveness of antibiotics in treating diseases in animals that endanger their well-being and production. Antibiotic Resistance and Antimicrobial Usage (AMU) in animals that produce food are known to be associated with human diseases caused by antimicrobial resistant bacteria, while it is unclear how much of an impact this has. AMR arises due to the overuse and misuse of antibiotics in cattle, which is concerning. Since the widespread overuse and abuse of antibiotics in livestock essentially causes AMR, it is important to address this issue.

To track the effectiveness of initiatives meant to lower AMR in the livestock industry, comprehensive AMU and AMR data are essential. The usage and sales of antibiotics are not fully reported in a number of nations, and the majority of what we currently know about the worldwide AMU is derived from modeling projections. There is inconsistent data on the prevalence of antibiotic resistance, especially in low- and middle-income nations, but some high-income areas have quite reliable data. It needs to be mentioned that worldwide standardized AMR data can be obtained through the use of surveillance guidelines and methods.

The two most important strategies for lowering AMU are medication-free prevention and sensible antimicrobial use. A better knowledge of the human- livestock interface is required to develop evidence-based and practical One Health solutions that will eventually reduce the burden of AMR in humans.

KEYWORDS

- Antibiotics

- Antimicrobial Resistance

- AMU

- One Health Approach

CITATION

Al Asad M, Katha ZS (2024) Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock-Human Interaction: A Critical Public Health Issue. JSM Microbiology 10(1): 1062.

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a significant worldwide public health risk that is gaining increased attention [1]. Considering that the widespread application of antibiotics in livestock production leads to the evolution of drug resistance, research is being done on the class of antibiotics that are effective against bacteria [2-4]. The reason for their broad usage in livestock is because they are primarily used as feed additives and for a variety of preventive purposes as growth boosters. Human medicine rarely employs similar procedures. Numerous accounts exist on the transmission of animal-resistant germs to humans [5]. It is unclear to what degree this occurs or how much the livestock industry adds to human AMR overall. The relationship between animals and humans in AMR is especially concerning when it comes to antibiotic resistance [6].

This is due to the fact that both humans and animals have commensal and harmful bacteria, and both fields employ the same types of antibiotics. The effectiveness of antibiotics in treating bacterial illnesses in animals that endanger their health, welfare, and productivity is also compromised by antibiotic resistance [7]. It is time to end the widespread use of antibiotics in the livestock industry to boost growth and serve as a regular preventive measure to make up for subpar animal husbandry and biosecurity. Although this presents a challenge for veterinary services, with careful handling, it can have a positive impact on both human and animal health.

In this section, we provide a global overview of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and Antimicrobial Use (AMU). Second, we examine the general effects of antibiotic resistance on animal health and talk about the connection between humans and animals’ resistance. Lastly, with the purpose of examining the various participants in One Health, the study sought to assess the AMR issue from a One Health perspective.

ANTIMICROBIAL USE AND RESISTANCE IN LIVESTOCK

Use of Antibiotic in livestock sector

Antibiotics are vital veterinary drugs that are given parenterally, orally through feed, orally by drinking water, orally via feed to cure bacterial infections, prevent disease in a herd, and at sub-therapeutic dosages to promote development in livestock. The significance of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine is listed [8]. World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) guidelines for veterinary usage are given in the rare instances when the same antibiotic class is crucial to both human and animal sectors, such as fluroquinolones and third- and fourth generation cephalosporins [9]. High-income nations, mainly those in North America and Europe, have national surveillance systems that record prescriptions for antibiotics, which should ideally be categorized by species of animal, age, and disease indication [10]. Nevertheless, only 6% of Low- And Middle- Income Countries (LMICs) keep an eye on AMU in animals [11] because they lack the ability and funding to set up and maintain a national surveillance system. As a result, there is a widespread lack of information on the precise dosage of antibiotics are employed and their intended usage.

According to estimates, 73% of the world’s AMU is made up of livestock. A recent study that included sales data from 41 nations across all continents predicted that this percentage will rise by 11.5% between 2017 and 2030, mostly in Asia [12, 13]. The expansion of livestock production is the primary cause of this rise in the demand for animal protein, especially in LMICs where AMU is indiscriminately and poorly regulated to make up for subpar animal husbandry techniques [13-15].

Comparably, laws that expressly forbid the use of antibiotics as growth promoters exist in LMICs such Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, and Thailand [16]; However, enforcing these laws can be difficult, and no economic impact analyses have been done expressly for the context of LMIC livestock production that evaluate the effects of limiting the use of antimicrobial growth promoters or the financial benefits of alternatives to antibiotics like better animal husbandry [17,18].

Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock

To determine the worldwide burden of AMR, the World Health Organization’s global AMR surveillance system gathers AMR data from a subset of indicator microorganisms [11]. However, there is no such global system in animals. Every year in Europe, countries in specific food animal species and age ranges accumulate data on AMR in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from food animals and their products. The most recent research covering the years 2017–2018 identified several encouraging changes in food animals: a) Extended-spectrum beta lactamase/ AmpC-producing Escherichia coli was less common, b) the percentage of fully susceptible E. coli increased significantly c) colistin resistance was rare, and d) no carbapenemase-producing

E. coli was found in poultry [19]. Similar animal AMR monitoring programmes have been put in place in North America. However, only 10% of LMICs nations reported tracking AMR in animals [20]. Van Boekel, et al. [21] examined point prevalence surveys to give an overview of AMR levels in animals and animal food products in LMICs in four bacterial species: E. coli, Campylobacter spp., non-typhoidal Salmonella spp., and Staphylococcus aureus between 2000 and 2018. This was done in the absence of national or regional AMR data.

ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE’S EFFECTS ON ANIMAL HEALTH

AMR’s effects on animal health have received far less attention than its effects on human health. Like humans, animals suffering from AMR will experience infections that otherwise would not have happened, a higher rate of treatment failures, and a higher degree of illnesses [22]. Furthermore, the health and welfare of animals will suffer if treatment options are lost due to resistance developing or usage being restricted [4]. AMR may result in financial losses for owners of animals used to produce food and commodities in two ways: directly through increased mortality and indirectly through decreased growth and productivity, decreased feed conversion, and early culling of breeding and production animals. This could eventually lead to increased costs for final consumers of goods and animal-produced food [22,23].

Food and products of animal origin have been traded globally. Consequently, resistant bacteria chosen by antimicrobial usage in one nation can lead to issues in multiple other nations, as demonstrated by the growth of E. coli resistant to cephalosporins imported from England from grill parents via Sweden to Denmark, where it was found in the meat from broilers [24,25]. Effects from AMR are particularly likely to affect the output and trade of livestock and livestock products [26]. According to a 2017 World Bank report, the effects of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) are expected to reduce global livestock production by 3% to 8% annually by the year 2050. The high AMR-impact scenario for AMR’s effects on development and the economy predicts an 11% decline in livestock production by that year, with low- income countries expected to experience the largest decline [27].

Moreover, the effect of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) may be more pronounced in nations with higher rates of infectious disease burden, necessitating greater use of antibiotics. Because there is little biosecurity in place and animals and humans interact frequently in small- and medium-sized farming systems, Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) can spread from livestock to humans and between farms in Low- And Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) [28]. The detrimental effects of AMR in these nations have been made worse by weaker AMR surveillance systems and less regulation of antimicrobials, which are more likely to be of inferior quality, fabricated, or unregistered [16-28].

ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE’S EFFECTS AS SEEN FROM A ONE HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

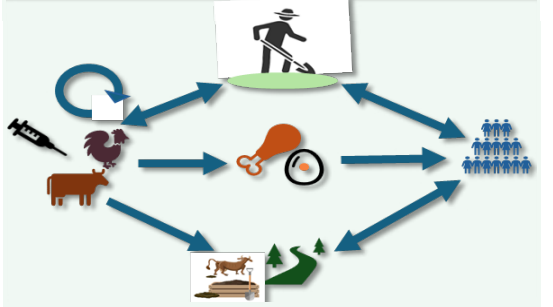

A collaborative effort across different disciplines to provide solutions for human, animal, and environmental health is known as the One Health approach [29]. There is strong scientific evidence that infections with resistant pathogens in companion and food-producing animals may have an impact on humans because of AMU [5-30]. Humans can acquire AMR from animals through contact, animal products contaminated with resistant organisms, or ingestion of undercooked food, depending on the species and production methods (Figure 1) [23-30]. In addition, unmetabolized antibiotics excreted by animals and the use of manure and urine from livestock production as fertilizers can both disperse antimicrobial resistant organisms from animal waste [31,32]. The extent of this zoonotic transmission is notably still unknown due to data gaps. Antimicrobial resistance is regarded as posing a serious threat to advancements in global health and development as well as the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include narrowing the inequality gap both within and between nations [33]. AMR is thought to be the cause of 25,000 human deaths in the European Union alone each year. If AMR levels rise further, numerous studies predict significant economic losses [27-34]. According to estimates, by 2050, the economic costs of AMR could account for 1.1% to 3.8% of GDP, cause 10 million deaths annually, and put a total of US$ 100 trillion in the economy at danger [27-36].

Figure 1 Antimicrobial resistance in livestock can spread to humans through the food chain, manure, the environment, and farmers who deal closely with the animals. It is unclear how important each of these several pathways is in comparison.

One Health Strategy to Address AMR

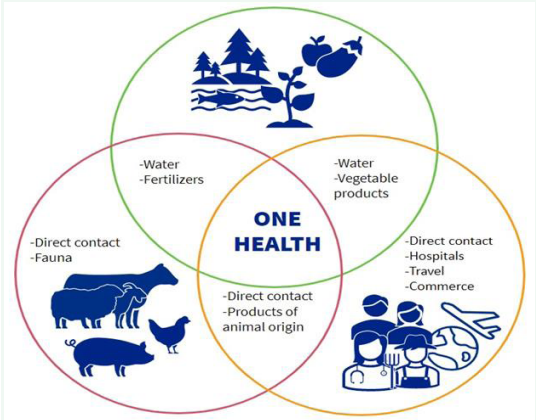

The One Health approach acknowledges the connections between the health of humans, animals, and the environment through a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach [37]. AMR represents an ecological challenge characterized by intricate interactions among diverse microbial populations, impacting the health of humans, animals, and the environment, as illustrated in (Figure 2) [38,39]. The rapid occurrence and dissemination of acquired AMR are attributed to the excessive use of antibiotics in human and food-producing industries, as well as environmental contamination with antibiotics. Addressing the resistance dilemma necessitates acknowledging this complexity and ecological interplay through a coordinated, multi-sectoral approach, such as the One Health framework. This framework is crucial for comprehending the ramifications of AMR and assessing the effectiveness of current and future interventions [39]. AMR is an intricate and multidimensional issue that impacts people, animals, and the environment. For this reason, it is imperative to tackle AMR using the One Health paradigm. Key components of the One Health strategy to address AMR are as follows [1,40].

Figure 2 One health surveillance for antimicrobial resistance.

Surveillance and Monitoring: Create integrated surveillance systems to keep an eye on how antimicrobials are used in agriculture, human health, and animals. Monitor the development and dissemination of pathogens that are resistant in both animal and human populations. Keep an eye out for antimicrobial residue contamination in the environment.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Establish interdisciplinary teams with doctors, veterinarians, environmental scientists, researchers, and legislators. Encourage cooperation to exchange knowledge and information between veterinary and human health institutions.

Education and Awareness: Initiate campaigns to educate the public and healthcare professionals about the responsible use of antibiotics. Including instructional initiatives in curriculum to raise students’ awareness of AMR from an early age.

ResponsibleAntimicrobialUse:Adheretorecommendations for the responsible use of antibiotics in healthcare environments, placing a priority on diagnosis before prescription. By means of rules and instruction, promote the prudent use of antibiotics in livestock farming, aquaculture, and agriculture.

Regulatory Measures: The distribution and sale of antimicrobials in veterinary and human medicine should be more strictly regulated. Prescription guidelines must be followed, and limits on the sale of antibiotics over the counter must be implemented.

Research and Innovation: Provide funds for the development of vaccines, alternative treatments, and novel antibiotics. To promote innovation, encourage cooperation between government organizations, academic institutions, and pharmaceutical companies.

Waste Management and Capacity Building: To avoid contaminating the environment, develop and implement appropriate pharmaceutical waste management protocols. To reduce the negative effects on the environment, track, and control how leftover or expired antibiotics are disposed of. At the same time, to improve their comprehension of AMR and the One Health approach, they offer training courses to environmental scientists, veterinarians, and healthcare professionals. Bolster the ability of laboratories to test for antibiotic susceptibility.

Early Detection and Provide Sustainable Practices: Provide quick ways to identify AMR in agricultural and clinical contexts. Create response plans so that, if resistance is found, prompt action can be taken. Encourage the creation and implementation of sustainable farming methods that lessen the need for antibiotics. Think about financial rewards for drug companies that responsibly develop antibiotics.

Global Cooperation: Form an international alliance to combat AMR with genuine action. For the fight against AMR to make meaningful progress, global action is required. Positioning AMR in the context of global politics and taking a One Health approach to its management is crucial to bringing about change [41].

PRIORITIES FOR TAKING ACTION IN PUBLIC HEALTH

Raising public awareness and offering education are crucial elements in tackling antimicrobial resistance AMR [42]. Healthcare professionals need to stay up-to-date with antimicrobial stewardship, as well as infection prevention and control practices [42]. In contrast, outpatient settings focus on patient education, diagnostic testing, and ensuring that antibiotics are used only when absolutely necessary for antibiotic stewardship. Table 1 provides details on different alternative strategies for tackling antimicrobial resistance. Table 1 outlines strategies that include improving the monitoring of antimicrobial use and resistance, encouraging the development of new antimicrobials, and enforcing stricter regulations on antimicrobial prescribing, dispensing, and usage. Other important actions involve fostering global cooperation, tackling the problem of substandard and counterfeit antimicrobials, promoting vaccination, and enhancing sanitation, hygiene, and biosecurity. Additionally, it is essential to explore alternatives to antimicrobials. Nevertheless, several challenges hinder the implementation of these strategies, such as limited awareness and understanding of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), insufficient human resources and capacity for AMR and Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS), inadequate funding for AMR and AMS initiatives, restricted laboratory capabilities for monitoring, issues with behavioral change, and ineffective leadership and multidisciplinary teams.

Table 1: Various alternative approaches for addressing global antimicrobial resistance [40].

|

Techniques |

Summary |

Benefits |

Challenges |

|

Antibiotic stewardship |

Using antibiotics rationally involves prescribing them only when necessary and ensuring the correct dosage is given. |

This approach preserves the effectiveness of antibiotics and helps reduce the development of resistance. |

Achieving this requires changes in behavior from both healthcare professionals and patients, and it is crucial to monitor compliance. |

|

Development of new antibiotics |

Investigating and developing new antibiotics that target previously unexplored bacterial mechanisms. |

This approach targets resistance to current drugs. |

Challenges include high costs, a lengthy development process, and the potential for cross-resistance. |

|

Combination Therapies |

Employing a combination of antibiotics with different mechanisms of action to treat infections. |

Combining antibiotics can enhance their effectiveness and reduce the likelihood of resistance. |

Challenges include complex dosing regimens, a higher risk of side effects, and the potential for antagonism between drugs. |

|

Phage Therapy |

Utilizing bacteriophages viruses that infect bacteria to target specific bacterial strains. |

This method offers a highly targeted approach and can be quickly adapted. |

Challenges include limited understanding of phage-bacteria interactions, regulatory hurdles, and variable effectiveness. |

|

Probiotics and Prebiotics |

Encouraging the growth of beneficial bacteria to outcompete harmful strains. |

This strategy supports a healthy microbiota and reduces available space for pathogens. |

Difficulties with colonization and persistence are among the challenges, as is the lack of understanding regarding which strains are best to utilize. |

|

Surveillance Systems |

Tracking and monitoring resistance patterns to guide treatment guidelines. |

It offers real-time data and helps guide treatment decisions. |

This approach can be resource-intensive and faces challenges in data sharing and harmonization. |

|

Environmental Regulations |

Minimizing antibiotic use in agriculture and industry to help limit the spread of resistance. |

This helps reduce the selection pressure for resistance. |

Enforcement of regulations, international cooperation, and economic ramifications are among the difficulties. |

|

One Health Approach |

Coordinating efforts across human, animal, and environmental health to address resistance. |

This approach tackles the complex sources of resistance spread. |

It requires interdisciplinary collaboration and faces challenges in communication and policy alignment. |

CONCLUSION

A “One Health” strategy that addresses human, animal, plant, and environmental health is crucial for the fight against AMR. This calls for quickening the pace of global development, developing innovative solutions to safeguard the future, working together to take more efficient action, investing in environmentally friendly solutions, and bolstering global accountability and governance. Animals and humans can both use the most antibiotic classes. When antimicrobials are only used as treatments, infrequently as prophylactics, and never as growth promoters, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) can be decreased. To ensure success, it will be necessary to monitor and manage the spread of resistant bacteria into the environment, as well as to enforce stringent and effective control over the kinds and quantities of antibiotics used in medical practices.

REFERENCES

- Sirwan Khalid Ahmed, Safin Hussein, Karzan Qurbani, Radhwan Hussein Ibrahim, Abdulmalik Fareeq, Kochr Ali Mahmood, et al. Antimicrobial resistance: impacts, challenges, and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health. 2024; 2: 100081.

- Organization WH, Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 2015.

- Samtiya M, Matthews KR, Dhewa T, Puniya AK. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Food Chain: Trends, Mechanisms, Pathways, and Possible Regulation Strategies. Foods. 2022; 11: 2966. doi: 10.3390/ foods11192966. PMID: 36230040; PMCID: PMC9614604. OIE, The OIE strategy on antimicrobial resistance and the prudent use of antimicrobials. 2016.

- Hoelzer K, Wong N, Thomas J, Talkington K, Jungman E, Coukell A. Antimicrobial drug use in food-producing animals and associated human health risks: what, and how strong, is the evidence? BMC Vet Res. 2017; 13: 211. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-1131-3. PMID: 28676125; PMCID: PMC5496648.

- Magnusson U, Moodley A, Osbjer K. Antimicrobial resistance at the livestock-human interface: implications for Veterinary Services. Rev Sci Tech. 2021; 40: 511-521. English. doi: 10.20506/rst.40.2.3241. PMID: 34542097.

- Bengtsson B, Wierup M. Antimicrobial resistance in Scandinavia after ban of antimicrobial growth promoters. Anim Biotechnol. 2006; 17: 147-56. doi: 10.1080/10495390600956920. PMID: 17127526.

- Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine. WHO. 2019.

- White A, Hughes JM. Critical Importance of a One Health Approach to Antimicrobial Resistance. Ecohealth. 2019; 16: 404-409. doi: 10.1007/s10393-019-01415-5. Epub 2019 Jun 28. PMID: 31250160.

- Sanders P, Vanderhaeghen W, Fertner M, Fuchs K, Obritzhauser W, Agunos A, et al. Monitoring of Farm-Level Antimicrobial Use to Guide Stewardship: Overview of Existing Systems and Analysis of Key Components and Processes. Front Vet Sci. 2020; 7: 540. doi: 10.3389/ fvets.2020.00540. PMID: 33195490; PMCID: PMC7475698.

- Global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (GLASS) report: early implementation 2020. WHO. 2020.

- Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, Robinson TP, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015; 112: 5649-5654. doi: 10.1073/ pnas.1503141112. Epub 2015 Mar 19. PMID: 25792457; PMCID: PMC4426470.

- Tiseo K, Huber L, Gilbert M, Robinson TP, Van Boeckel TP. Global Trends in Antimicrobial Use in Food Animals from 2017 to 2030. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020; 9: 918. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9120918. PMID: 33348801; PMCID: PMC7766021.

- Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, Pant S, Gandra S, Levin SA, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018; 115: E3463-E3470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717295115. Epub 2018 Mar 26. PMID: 29581252; PMCID: PMC5899442.

- Schar D, Sommanustweechai A, Laxminarayan R, Tangcharoensathien V. Surveillance of antimicrobial consumption in animal production sectors of low- and middle-income countries: Optimizing use and addressing antimicrobial resistance. PLoS Med. 2018; 15: e1002521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002521. PMID: 29494582; PMCID: PMC5832183.

- Goutard FL, Bordier M, Calba C, Erlacher-Vindel E, Góchez D, de Balogh K, et al. Antimicrobial policy interventions in food animal production in South East Asia. BMJ. 2017; 358: j3544. doi: 10.1136/ bmj. j3544. PMID: 28874351; PMCID: PMC5598294.

- Van Boeckel TP, Glennon EE, Chen D, Gilbert M, Robinson TP, Grenfell BT, et al. Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals. Science. 2017; 357: 1350-1352. doi: 10.1126/science. aao1495. Epub 2017 Sep 28. PMID: 28963240; PMCID: PMC6510296.

- Authority, E.F.S., E.C.f.D. Prevention, and Control, The European Union Summary Report on Antimicrobial Resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2017/2018. EFSA Journal, 2020. 18: e06007.

- Wi YM, Choi JY, Lee JY, Kang CI, Chung DR, Peck KR, et al. Emergence of colistin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST235 clone in South Korea. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017; 49: 767-769. doi: 10.1016/j. ijantimicag.2017.01.023. Epub 2017 Apr 6. PMID: 28392440.

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016; 16: 161-168. doi: 10.1016/ S1473-3099(15)00424-7. Epub 2015 Nov 19. PMID: 26603172.

- Agency EM. European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption. 2017.

- Bengtsson B, Greko C. Antibiotic resistance--consequences for animal health, welfare, and food production. Ups J Med Sci. 2014; 119: 96- 102. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.901445. Epub 2014 Mar 28. PMID: 24678738; PMCID: PMC4034566.

- Catry B, Van Duijkeren E, Pomba MC, Greko C, Moreno MA, Pyörälä S, et al. Reflection paper on MRSA in food-producing and companion animals: epidemiology and control options for human and animal health. Epidemiol Infect. 2010; 138: 626-644. doi: 10.1017/ S0950268810000014. Epub 2010 Feb 9. PMID: 20141646.

- Aarestrup FM. The livestock reservoir for antimicrobial resistance: a personal view on changing patterns of risks, effects of interventions and the way forward. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015; 370: 20140085. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0085. PMID: 25918442; PMCID: PMC4424434.

- van Duijkeren E, Catry B, Greko C, Moreno MA, Pomba MC, Pyörälä S, et al. Review on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011; 66: 2705-2714. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr367. Epub 2011 Sep 19. PMID: 21930571.

- Wall BA, Mateus ALP, Marshall L, Pfeiffer DU, Lubroth J, Ormel HJ, et al. Drivers, dynamics and epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in animal production. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016.

- Jonas Olga B, Irwin Alec, Berthe Franck, Cesar Jean, Le Gall Francois G, Marquez Patricio V, et al. Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future (Vol. 2): final report. HNP/Agriculture Global Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative. 2017.

- Elizabeth A Ashle, Arlene Chuay, David Dance, Nicholas P Day, Mehul Dhorda, Philippe Guerin, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in low and middle income countries: an analysis of surveillance networks Report 2017. 2020.

- Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance: 2014 Summary. World Health Organization. 2014.

- Tang KL, Caffrey NP, Nóbrega DB, Cork SC, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW, et al. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food- producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2017; 1: e316-e327. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30141-9. Erratum in: Lancet Planet Health. 2017 Dec;1(9): e359. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30157-2. PMID: 29387833; PMCID: PMC5785333.

- Rushton J. Anti-microbial Use in Animals: How to Assess the Trade-offs. Zoonoses Public Health. 2015; 62: 10-21. doi: 10.1111/ zph.12193. PMID: 25903492; PMCID: PMC4440385.

- Wu Z. Antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals in China. 2019.

- Organization WH. Fact sheets on sustainable development goals: health targets. Antimicrobial resistance, 2017.

- Cassini A, Högberg LD, Plachouras D, Quattrocchi A, Hoxha A, Simonsen GS, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life- years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019; 19: 56-66. doi: 10.1016/ S1473-3099(18)30605-4. Epub 2018 Nov 5. PMID: 30409683; PMCID: PMC6300481.

- O’Neill J. Review on antimicrobial resistance: tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. Government of the United Kingdom. 2016.

- Michele Cecchini, Julia Langer, Luke Slawomirski. Antimicrobial resistance in G7 countries and beyond: Economic issues, policies and options for action. 2015.

- Danasekaran R. One Health: A Holistic Approach to Tackling Global Health Issues. Indian J Community Med. 2024; 49: 260-263. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_521_23. Epub 2024 Mar 7. PMID: 38665439; PMCID: PMC11042131.

- Tang KWK, Millar BC, Moore JE. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Br J Biomed Sci. 2023; 80: 11387. doi: 10.3389/bjbs.2023.11387. PMID: 37448857; PMCID: PMC10336207.

- Ahmad N, Joji RM, Shahid M. Evolution and implementation of One Health to control the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes: A review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023; 12: 1065796. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1065796. PMID: 36726644; PMCID: PMC9884834.

- Mitchell J, Cooke P, Ahorlu C, Arjyal A, Baral S, Carter L, et al. Community engagement: The key to tackling Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) across a One Health context? Glob Public Health. 2022; 17: 2647-2664. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.2003839. Epub 2021 Dec 9. PMID: 34882505.

- O’Neill J, Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. 2016.

- Steward Mudenda, Billy Chabalenge, Victor Daka, Ruth Lindizyani Mfune, Kyembe Ignitius Salachi, Shafiq Mohamed, et al. Global strategies to combat antimicrobial resistance: a one health perspective. Pharmacology & Pharmacy. 2023; 14: 271-328.