Correlation between Migraine and Cardiovascular Disease: State of Art

- 1. Interdepartimental Centre for Research in Molecular Medicine (CIRMC), University of Pavia, Italy

- 2. Department of Cardiology, IstitutiClinici di Pavia e Vigevano University Hospital, Italy

- 3. IRCCS San Donato Hospital, San Donato Milanese, Italy

Abstract

Migraine, and specifically migraine with aura (MA), has been associated with increased risk of major cardiovascular disease (CVD). Numerous studies have indicated that patients with migraine have an increased risk of vascular disease. The association between migraine and ischemic stroke was the earliest to be recognize but migraine has been associated also with myocardial infarction, hemorrhagic stroke, retinal vasculopathy, incidental brain lesions and with peripheral artery disease.

To better define the biological link between migraine and vascular events, several mechanisms have been proposed, but the precise mechanisms are currently unknown.

In this review, we briefly summarize the evidence supporting a clinical association between migraine and the most common cardiovascular disease, exploring hypothesis that may explain the association and dealing with gender differences and pharmacological treatment issues.

Understanding the mechanism of cardiovascular disease in migraineurs may be useful in determining effective strategies for cardiovascular prevention and, for acute preventing treatment of migraine. The link of cardiovascular disease and peripheral artery disease with migraine may be present, but it is difficult to separate out from common vascular risk factors often present at the same time such as smoking, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. The presence of coronary artery disease or peripheral vascular disease limits the use of certain acute and preventive migraine treatments. Any migraine treatment that decreases the width of a blood vessel cannot be used in those who have or might have cardiovascular disease.

Future targeted research is warranted to identify preventive strategies to reduce the risk of future cardiovascular disease among patients with migraine. These results further add to the evidence that migraine should be considered an important risk marker for cardiovascular disease, at least in women.

Keywords

- Cardiovascular disease

- Migraine

- Stroke

- Coronary artery disease

- Silent myocardial ischemia

Citation

Bozzini S, Falcone C (2017) Correlation between Migraine and Cardiovascular Disease: State of Art. JSM Pain Manag 2(1): 1007

ABBREVIATIONS

CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; IS: Ischemic Stroke; MA: Migraine with Aura; SMI: Silent Myocardial Ischemia; MTHFR: Methylenetetra Hydrofolate Reductase; VWF: Von Willebrandfactor; ACE-DD: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Gene Deletion Polymorphism; MI: Myocardial Infarction

INTRODUCTION

Migraine, and specifically migraine with aura (MA), has been associated with increased risk of major cardiovascular disease (CVD) [1].

Migraine is the most common neurological disorder and major cause of disability in the western world, it causes substantial impairment in daily activity and productivity. An aura ispresent in up to 30% of migraineurs, usually during the hour preceding the headache [2].

The underlying pathophysiology of migraines is not fully understood. Findings have suggested that deregulation of the sympathetic nervous system and alterations in the craniovascular circuitry may be involved [3]. In support of vascular etiology, it was demonstrated that migraines also have been linked with vasomotor disorders like Raynauds and Prinzmetal’s angina [4- 7] and to the possibility of an association between migraine headaches and cardiovascular events, like angina, myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.

In multiple population-based studies was shown that patients with migraine are more likely to have chest pain symptoms [8- 10]. Among which one large study in Australian patients showed a relationship between migraine and cardiovascular events and noted that subjects with migraine were twice as likely to have a self-reported history of myocardial infarction [11].

To better define the biological link between migraine and vascular events, several mechanisms have been proposed, but the precise mechanisms are currently unknown. Migraine has been associated with an unfavourable cardiovascular risk profile [12] and migraine frequency and severity have been associated with increased body mass index [13]. It has recently been shown that in women with indications for coronary angiography, those with migraine had less severe coronary artery disease (CAD) than those without migraine [14]. It is possible that patients with migraine have more vascular symptoms and events due to the migraine-specific vascular dysfunction compared with individuals with the same degree of atherosclerosis [7,15], and also that a synergistic effect exists between the vascular and endothelial dysfunction of migraine and factors that increase the risk of thrombotic vascular events.

Since migraine is associated with cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and with their risk factors. This should be taken into account in order to properly identify individuals at particularly high risk, as well as in order to plan treatment that targets not only migraine, but the complications potentially associated with migraine.

In this review, we briefly summarize the evidence supporting a clinical association between migraine and the principal cardiovascular diseases, exploring hypothesis that may explain the association and dealing with gender differences and pharmacological treatment issues.

Peripheral arterial disease

Numerous studies have indicated that patients with migraine have an increased risk of vascular disease and the earliest to be recognized was the association between migraine and ischemic stroke [16-18]. However, migraine has been associated also with myocardial infarction, hemorrhagic stroke, retinal vasculopathy, incidental brain lesions, and with peripheral artery disease [19- 22].

In the mechanisms predisposing individuals to atherosclerosis and vascular diseases play an important role the endothelial and arterial dysfunction [23]. Several studies support an alteration of arterial function among subjects with migraine but findings on the endothelial function are less clear. The endothelial dysfunction causes a reduction in endothelium-dependent vasodilation and the induction of a specific state of endothelial activation. It was demonstrating that endothelial dysfunction was characterized by a proinflammatory state which promotes atherogenesis, pathological inflammatory processes, and vascular disease and, for these reasons represents an early step in the development of atherosclerosis [24].

Regarding arterial function, the mechanisms underlying the association with migraine may involve both structural and functional changes in the arterial wall. The possible hypotheses include alterations in vessel wall structure in migraineurs as supported by the presence of impaired serum elastase activity [25], higher sympathetic tone [26, 27], use of drugs such as triptans and ergot derivatives, or it may represent a primary alteration linked to the presence of migraine itself [28].

Genetically determined conditions that include among their clinical manifestation attacks of migraine as cerebrovascular events supported the suggestion that a common alteration may cause both migraine and CVD. One of this condition is CASADIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy), that was caused by mutation in Notch 3 gene(on chromosome 19). Animal models that express human mutation in Notch3 have abnormal myogenic responses and significantly larger brain infarcts after middle cerebral artery occlusion, compared with subjects without these mutations [29].

Stroke

Migraine has traditionally been viewed as a benign, chronic episodic condition. However, accumulating evidence suggests that migraine can be associated with increased risk for stroke and white matter lesions [30-34]. Migraine overall and MA, but not migraine without aura, have been associated with an increased risk of ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke.

These two conditions have some clinical contrasts. For example, unlike migraine, stroke is an acute and often catastrophic cerebrovascular event. In addition, stroke is the leading cause of acquired physical disability in adults, and the second leading cause of mortality worldwide [35], in contrast to the perceived benign nature of migraine.

Abundant observational data from different population-based studies have firmly established a link between migraine and ischemic stroke (IS) [34,35]. The most recent meta-analysis [34] of 13 case-control and eight cohort studies showed a link between migraine and ischemic stroke with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.04 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.72–2.43).

A feature of this relationship between migraine and stroke is is bidirectionality [36]. Headache is associated with IS in 17– 34% of patients [37] and bears its own classification in the 2013 IHS classification. It is described as a new headache developing simultaneously with or in close temporal relationship to signs or other evidence of IS associated with neuroimaging confirmation of ischemic infarction. A number of neuro imaging studies over the past decade revealed a higher prevalence of subclinical brain abnormalities in migraineurs, including infarcts and white matter hyperintensities, suggesting acute or chronic ischemic disease [38].

Headache is present at onset in 43–60% of cases, is persistent in 25–30%, and starts after in 14–27% of ischemic events. Headache associated with IS is more frequently observed in migraineurs [39], where it may sometimes mimic a migraine attack, although the studies reporting headache as a symptom of stroke are not recent and do not take into account the HIS classification for a definite diagnosis of the headache type.

A multicentric Italian study [35] on IS patients was carried out to evaluate whether the vascular risk profile variation had a predictive value on the migraine subtype. In this study the migraine risk increased as the number of cardiovascular risk factors decreased and the number of thrombophilic variants increased, or in the presence of right-to-left shunt (RLS) (OR = 2.41; 95% CI 1.37–3.45). Therefore, there seems to be an inverse relationship between migraine and vascular risk factors in stroke at a young age.

As discussed above, the association between migraine and ischemic stroke was the earliest to be recognized but migraine has been associated also with hemorrhagic stroke. A recent meta-analysis reported an overall pooled adjusted risk estimate (RR) of hemorrhagic stroke of 1.48 (95% CI 1.16-1.88), which was slightly higher in subjects with MA (RR 1.62, 95% CI 0.87-3.03) [40]. In this study the relative risk estimated are similar regarding the association of intracerebral hemorrhage with migraine, although of a smaller magnitude, and particularly regarding MA in women.

Ischemic heart disease

Several studies demonstrated that there may be an association between migraine and systemic cardiovascular event risk (e.g. myocardial ischemia and infarction, cardiovascular mortality, peripheral vascular disease).

Contrasting data are present: previous population studies have supported the relationship between migraine and coronary heart disease, but an increased risk of cardiac events in patients with migraine was not confirmed by some meta-analysis.On the contrary a recent meta-analysis by Sacco S et al., (2015) indicate an increased risk of myocardial infarction and of angina in migraineurs compared to non migraineurs.

The Women’s Health Study [42] demonstrated an association between MA and both CVD and stroke in 27,519 female patients with an 11.9 year follow-up, stratified by the Framingham risk score for coronary heart disease. Female migraineurs with a low-Framingham score had an OR of 3.88 (95% CI 1.87–8.08) for ischemic stroke and 1.29 for myocardial infarction (95% CI 0.40– 4.21). Conversely, females with MA in the high-risk group had an OR of 1.0 (CI 95% 0.24–4.14) for stroke, and 3.34 (95% CI 1.50– 7.46) for myocardial infarction. Instead, women with migraine without aura did not have any increased risk of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke.

Furthermore, as part of the Physician’s Health Study, men with any migraine (with or without aura) were reported to have at increased risk for major cardiovascular disease, a finding supported by a 42% increased risk of myocardial infarction [43].

However, the meta-analysis by Schurks et al. [44], confirmed the increased ischemic stroke risk in migraine but there was neither statistically significant difference for the association between any migraine and myocardial infarction, nor for the association between migraine and death due to cardiovascular events.

Lastly, a population-based study found that migraine is associated with myocardial infarction, stroke and claudication, also after adjustments for gender, age, disability, treatment, and vascular risk factors [45].

Although an earlier meta-analysis of eight studies did not show an increased risk of myocardial infarction among migraineurs(OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.95–13.2) [44], a more recent large case-control study suggested a higher risk (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.7–2.76) [45]. Most recently, a population-based prospective study showed an increased risk of ischemic heart disease in participants between the ages of 18 and 45 [46]. Likewise, a large prospective cohort with a median follow-up of 26 years suggested increased cardiac mortality among migraineurs with aura [47]; however, the association was not significant in a meta-analysis [24].

The precise mechanisms by which migraine may lead to cardiovascular events remains unclear. Migraine has been associated with a more unfavourable cardiovascular risk profile [12], with increasing levels of prothrombotic or vasoactive factors [48-51], as well as the C677T polymorphism in the methylenetetra hydrofolate reductase gene that has also been associated with increased homocysteine levels [52].

Although it has been shown that migraine is associated with increased levels of total cholesterol and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) [12], a comprehensive evaluation of the association between biomarkers of CVD and migraine is lacking.

In 2007, Kurth T et al. [43], evaluate the association between traditional and novel biomarkers for CVD e migraine in the Women’s health Study (WHS). They found an association with total cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, Apo B100 and CRP but the magnitude of association, however, was only modest. Instead, they don’t find a pattern suggesting any association between migraine frequency and elevated biomarker levels.

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, patients with headache had about twice the odds to have a history of angina than controls and in particular the MA group had the highest risk score.

Another fascinating field of research regarding the correlation between headache and ischemic heart disease includes the silent myocardial ischemia (SMI), defined as an objective documentation of myocardial ischemia in the absence of angina or anginal equivalents [53].

The presence or absence of anginal symptoms may be partly explained by individual differences in the pain threshold [54-56]. In addition, chemical factors released in response to ischemia which stimulate cardiac afferent pain fibers may be responsible for cardiac pain; various chemical agents have been implicated as a stimulus for angina pectoris during ischemia [57]. However, the mechanism underlying SMI is not well understood, and many theories have been advanced.

A recent work on a large CAD population by Falcone C et al., (2013) [10] suggests that the presence of primary headache could be a useful marker to identify subjects with susceptibility to pain and that its absence could be correlated with SMI. Data deriving by this study suggest that symptomatic patients with primary headache were more prone to pain. In patients with CAD, the correlation between the absence of symptoms during exercise-induced myocardial ischemia and a history negative for headache seems to confirm a generalized hyposensitivity to pain.

Several factors have been related to the absence of symptoms during myocardial ischemia, but the precise mechanisms responsible for the lack of pain have not yet been fully elucidated [54-56].

Granot et al. [57] demonstrated that the absence of pain in acute MI was associated with attenuated pain perception in response to various stimuli, and enhanced pain scores were reported in the MI patients with pain compared to those without pain. On the other hand, the onset of headache is widely attributed to a state of hypersensitivity to pain [58].

Therefore, the presence of headache in patients with known CAD decreases the probability of their having SMI, whereas the absence of headache recommends a close monitoring for those patients with risk factors for CAD, because in these patients, the risk of developing SMI might be increased.

Gender differences

The prevalence of migraine is lower in men than in women, and women report a longer attack duration, increased risk of headache recurrence, greater disability, and a longer period of time required to recover [59]. As previously described, migraine has been identified as a risk factor for vascular disorders. This happens predominantly in women, but because of the scarcity of studies in this field, the comparative risk in men has yet to be established.

Indeed, most of the studies in this field were performed in women. In 2006 Ahmed B et al. [14], suggested that among women undergoing coronary angiography for suspected myocardial ischemia, those with a history of migraine have less severe coronary artery disease on angiography and lower coronary artery severity scores compared with women who did not report migraine headaches. This difference remained significant after adjustment for age and other significant cardiac risk factors.

Subsequently, a study conducted in a large prospective cohort of healthy middle-aged men showed that migraine was associated with increased risk of subsequent major CVD, which was driven by increased risk of MI [45]. In particular, men who reported migraine had multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) of 1.24 (1.06-1.46; P =0.008) for major CVD, 1.12 (0.84-1.50; P =0.43) for ischemic stroke, 1.42 (1.15-1.77; P<0.001) for myocardial infarction, 1.05 (0.89- 1.24; P =0.54) for coronary revascularization, 1.15 (0.99- 1.33; P =0.068) for angina, and 1.07 (0.80-1.43; P =0.65) for ischemic cardiovascular death, compared with men without migraine.

More recently, a prospective cohort study in women with more than 20 years of follow-up confirm a consistent link between migraine and cardiovascular disease events, including cardiovascular mortality [60].

The major factor in determining the sex differences in migraine risk and characteristics seems to be the female sex hormones, but there is also evidence to support underlying genetic variance. Although migraine is often recognised in women, it is much less diagnosed in men, resulting in suboptimal management and less participation of men in clinical trials.

Possible mechanism linking ischemia to migraine

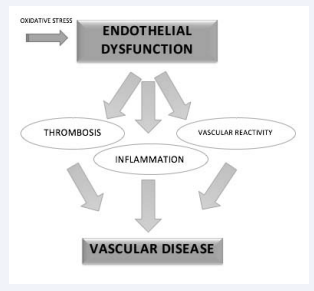

One of the main mechanisms that might explain the relationship of migraine to vascular factor and ischemic heart disease is endothelial dysfunction, characterized by reduction in bio availablility of vasodilator, increase in endothelial-derived contracting factors, and consequent impairment of the reactivity of the vasculature, including the microvasculature [61]. It also comprises endothelial activation, with a procoagulatory, proinflammatory and proliferative state, which predisposes to atherogenesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Possible mechanism of ischemia in migraine.

In this context, endothelial dysfunction is associated with an increased rate of cerebro- and cardiovascular ischemic events [61]. One of the most important biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction is VWF (von Willebrand factor). Previous studies demonstrated that the VWF antigen and its activity were significantly higher in subjects with migraine that non-migraine controls [62,63]. Other studies in patient with migraine without aura, have been demonstrated that VWF soluble intercellular adhesion molecule levels were also significantly higher than healthy control subjects [64].

In addition, migraine is associated with reductions in the number and function of endothelial progenitor cells, serving as a marker for dysfunctional endothelium [46]. Increases in platelet function [66-68] and thrombin markers [48] have been associated to migraine. However, the contribution of hypercoagulability to migraine-related ischemic disease is uncertain. A group of prothrombotic circulating serum immunoglobulins (aCL) are associated with silent white matter lesions in migraineurs [69], and with stroke [70], but no evidence of correlation to migraine are present [69].

In the pathogenesis of migraine inflammation seems to have an important role [71] and several studies demonstrating the association of migraine with inflammatory markers [72]. Clinical investigation of markers of oxidative stress in a migraine population during, after and between migraine attacks has yielded support for the association [73].

One of the genetic factors that may increase susceptibility to oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction and, possibly, stroke include the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene deletion polymorphism (ACE-DD), and the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) C677-TT polymorphism. MTHFR T/T genotype in increasing migraine susceptibility, with the greatest effect in those with aura [350]. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) is a key enzyme in the metabolism of homocysteine in which the most common mutation, C677T, has been implicated as a genetic stroke risk factor [74] and the TT genotype is associated with an increased risk of MA, independent of other cardiovascular risk factors [12].

The relationship of ACE-DD genotype to ischemic stroke and cardiovascular disease is controversial [75-78], but it has been independently linked to lacunar infarction [79] in the absence of carotid atheroma [80], and to leaukoariosis [81]. The ACE-DD polymorphism has been associated with migraine, both with [82] and without aura [83]. In particular, ACE-DD was associated with increased frequency of attacks in migraine without aura population [83].

Treatment

Understanding the mechanism of stroke in migraineurs may be useful in determining effective strategies for stroke prevention and, for acute preventing treatment of migraine.

Subjects with migraine, like other individuals, should avoid cigarettes smoking and manage cardiovascular risk factor, such us hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus, and should be cautioned to avoid the use of vasocostrictive drugs, including triptans. In fact, although triptans are generally considered safe for use in migraine, caution is warranted in those with multiple vascular risk factors. The presence of known vascular disease is a contraindication to triptan use.

Migraine preventive strategies become very important in individuals with vascular disease and migraine, as acute treatment options are limited.

As regard women with migraine, they should avoid oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives, particularly in presence of MA and vascular risk factors, if they are over the age of 35, or have a personal of family history of thrombosis [84].

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The link between CVD and migraine may be present, but it is difficult to separate out from other risk factors often present at the same time such as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and other common vascular risks. Results derived from previous studies add to the evidence that migraine should be considered an important risk marker for cardiovascular disease, at least in women. Future targeted research is warranted to identify preventive strategies to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease among patients with migraine.

The presence of coronary or peripheral vascular disease limits the use of certain acute and preventive migraine treatments. Understanding the mechanism of CVD in migraineurs may be useful in determining effective strategies for CVD prevention and, for acute preventing treatment of migraine. All medicines that cause artery narrowing should be avoided in the presence of cardiovascular or peripheral vascular disease, but there remain multiple effective treatments to reduce migraine pain and frequency.

Future targeted research is warranted to identify preventive strategies to reduce the risk of future cardiovascular disease among patients with migraine. In addition, future studies should focus on defining migraineurs at especially higher risk and it is important to assess how migraine treatment modifies the risk. The importance of cardioprotective medications in the context of migraine treatment should be assessed. Finally, clinicians should have heightened vigilance for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in migraineurs, such as obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

REFERENCES

2. Silberstein SD. Migraine. Lancet. 2004; 363: 381-391.

36. Bousser MG, Welch KM. Relation between migraine and stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2005; 4: 533-542.

37. Katsarava Z, Weimar C. Migraine and stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2010; 299: 42-44.

53. Gutterman DD: Silent myocardial ischemia. Circ J. 2009; 73: 785-797.