Pain in Advanced Breast Cancer in Uganda

- 1. Little Hospice Hoima, Hospice Africa Uganda

- 2. Hospice Africa Uganda, Kampala

- 3. Professor of Palliative Care, Makerere University and the Institute of Palliative Care, Hospice Africa Uganda

Abstract

Background: Breast cancer incidence in sub-Saharan Africa is on the rise. Often, owing to poor access to healthcare services, it presents late and tumours are often inoperable. This gives rise to a burden of pain associated with tumour growth that is rarely present in countries with more developed healthcare systems.

Purpose: To understand more fully the burden of pain associated with breast cancer: the causes and management.

Method: A retrospective analysis of patients enrolled under Hospice Africa Uganda, at Little Hospice Hoima. Using data from their files, pain scores, descriptions and management will be assessed. Patients will be divided into non-mastectomy and mastectomy groups so as to better understand the causes of pain.

Results: Sixty-seven files were analysed (66 female, 1 male), mean average age 52: of these, 47 never underwent mastectomy (Group A), 7 had mastectomy while under Little Hospice Hoima and 13 had mastectomy prior to enrolment. Those following mastectomy generally had a lower pain score than those associated with tumour growth. Both groups had a high burden of neuropathic pain, with those having undergone mastectomy tending to suffer more from neuropathy than those who had not. In general, those in Group B reported an improvement in pain severity following mastectomy. In Group C, 38% were taking opioid analgesia and 69% were taking an adjuvant (amitriptylline). In contrast, among those in Group A 60% were taking an opioid, while only 40% were taking adjuvant therapy. 40% of patients had tried herbal therapy before presenting to health services, contributing towards late presentation and advanced disease stage.

Conclusion: This analysis shows on a small-scale that the burden of neuropathic pain in breast cancer among both non-mastectomy and mastectomy patients is significant and should always be considered when prescribing analgesia. In line with WHO guidelines on types of cancer pain, those patients likely to be suffering from ‘nerve compression pain’ (i.e. those with significant tumour growth) were more likely to be on opioid analgesia than those with ‘nerve injury pain’ (i.e. post-mastectomy), who were more likely to be taking amitriptyline, either as an adjuvant drug or by itself. However, there is a significant amount of crossover between the two groups and each patient should be managed according to their specific pain descriptions and clinical assessment.

Citation

Hughes EC, Zirimenya L, Merriman A (2017) Pain in Advanced Breast Cancer in Uganda. JSM Pain Manag 2(1): 1006.

BACKGROUND

The incidence of breast cancer in economically developing countries such as Uganda is on the rise. Whilst cervical cancer remains the most common female cancer in Uganda, breast cancer is second, with an incidence increase rate of 3.7% [1]. Between 1961 and 1995 the incidence doubled from 11 per 100,000 to 22 per 100,000[2] and in 2010, the age-standardised incidence rate was 31.2 per 100,000 [1]. This is thought to be a result of changes in lifestyle (e.g. changes in reproductive patterns, increased obesity, physical inactivity), increased survival from other diseases and longer life expectancy and an increase in screening and diagnosis. However, there is still a great number of patients presenting late, with advanced disease. Some studies have shown that up to 87% of women with breast cancer in developing countries present with late disease [3]. A study in Ghana revealed over half of their subjects presented at Stages 3 or 4 [4].

It is widely agreed across breast cancer literature that presenting symptoms are often physical changes: a lump, skin changes, nipple tethering or discharge. Medscape [5] states that only 5% of patients with a malignant mass present with breast pain, and Cancer Research[6] advise on their website that breast pain is ‘not normally due to cancer’. In a study of 37 Hong Kong Chinese women, 36 of them presented with a lump and one with nipple discharge [7]. In the aforementioned study conducted in Ghana, 76% presented with a lump and none presented with breast pain [4]. On the other hand, a study conducted in Nigeria [8] found that ‘breast pain was a statistically significant presentation in patients with malignant breast disease’.

Pain was found to be one of the top ten most prevalent symptoms among patients on the Palliative Medicine Program of the Cleveland Clinic [9], and a systematic review [10] found that over 50% of patients with advanced cancer suffered from fatigue, pain, lack of energy, weakness and appetite loss. Despite WHO recommendations [11] on effective pain management in cancer patients, a study published in 2007 [12] demonstrated that 64% of patients categorized as having advanced, metastatic or terminal disease suffered from pain. Across all of the cancer patients included in the study, over one-third scored their pain as moderate or severe. In countries where healthcare services are accessible and screening programmes more widely established, cancer rarely presents for the first time as ‘advanced’. However in countries such as Uganda, presentation, diagnosis and treatment can all be delayed, giving rise to a greater number of patients with advanced and painful disease.

Moreover, a difference in causes of pain exists between patients who have undergone mastectomy (post-mastectomy pain or PMP) and those who have pain related to tumour growth. This will be discussed further later, but it is also important to highlight the distinction between nociceptive and neuropathic pain, as each warrants specific pharmacological management and will be explored in this study. Nociceptive pain is usually described as ‘throbbing’ or ‘aching’, while neuropathic pain is ‘pricking’, ‘burning’ or the sensation might be described as insects crawling or biting. Typically adjuvant therapy such as amitriptyline is used for the latter - through a number of pharmacological actions [13] including blocking noradrenaline and serotonin re-uptake, it has been shown to have an effect on central pain mechanisms. Tricyclic antidepressants have been shown to relieve pain in one in every 2-3 patients with peripheral neuropathic pain. While opioid analgesia[14] tends to be more effective in patients with nociceptive pain, it has been shown to have some benefit in relieving neuropathic pain as well, particularly peripherally. Consequently, pain management in breast cancer patients cannot be categorized absolutely: causes, effects and complex pharmacological interactions combine to give rise to a complicated and individual pain experience for each patient (Figure 1).

Figure 1 A patient with an advanced breast tumour.

OBJECTIVES

This study was undertaken to further understand the type and severity of pain in advanced breast cancer patients. Further, it enhances understanding of the causes of pain in a breast cancer patient: both post-mastectomy pain and pain as a direct result of the tumour will be explored. In this way, management of pain in breast cancer patients can be better executed.

METHOD

Little Hospice Hoima (LHH) is a branch of Hospice Africa Uganda (HAU) and provides palliative care services to 590 adults and children in the Albertine region of Uganda. The majority of patients enrolled have cancer and/or HIV.

A retrospective analysis of patient records was carried out. Seventy patients with breast cancer enrolled on the programme since 2010 were selected at random and their files analysed. Patients were divided into three groups: Group A never underwent mastectomy, Group B underwent mastectomy whilst on the programme and Group C had already undergone mastectomy on enrolment to the programme. Each file was then analysed according to mention of breast pain on admission, the severity of pain and the description. Type of analgesia prescribed was also recorded: either non-opioid only (step 1 on the WHO analgesic ladder) [11] opioids and/or an adjuvant (in this setting, the adjuvant was always amitriptyline). Group B were analysed specifically to see whether there was an improvement in pain severity and/or change in description of pain following mastectomy.

Other treatment protocols such as chemo- and radiotherapy were also recorded, as was the number of those who had undergone biopsy, and those who had used herbal treatment. Finally, patient outcomes were analysed.

Pain was scored using a scale 0-5, with 0 being equivalent to no pain and 5 being unbearable. Patients under HAU are asked to score their pain using either the ‘hand scale’ or a visual scale depicting jerry cans at various levels of ‘fullness’, with the empty can representing ‘no pain’ and the fullest representing the most pain [15].

RESULTS

Seventy patient files were analysed, with three files being excluded from the study. One of these patients had a lumpectomy that revealed fibroadenoma and another had mastectomy which subsequently revealed no cancerous cells. The third, on close analysis of the file, never had a biopsy and clinically did not appear to have a malignancy despite being referred as a cancer patient.

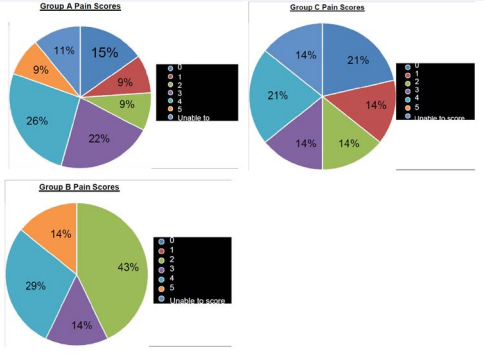

One patient was male and the age range was 16 -94, with an average age of 52 (Table 1) (Figure 2-4)

.Figure 2-4 Over 80% of both Groups A and B reported pain, with over half of both groups scoring their pain at 3-5 (considered as ‘moderate-severe’). Only 38% of Group C (those who have undergone mastectomy at the time of scoring) give a severity of 3 or 4, with none scoring their pain as 5

The words ‘burning’ and ‘pricking’ were used most commonly in both groups (Figure 5). This suggests a predominance of neuropathic rather than nociceptive pain. ‘Insect biting’ and ‘Insect crawling’ are also common ways to describe neuropathic pain. Taking this into account, the post-mastectomy patients described their pain as neuropathic more than twice as often as nociceptive. The ratio of nociceptive vs neuropathic pain described by the non-mastectomy group was 1:1.3, suggesting a more equal distribution between both types of pain in those with tumour-related symptoms.

Figure 2-4 Over 80% of both Groups A and B reported pain, with over half of both groups scoring their pain at 3-5 (considered as ‘moderate-severe’). Only 38% of Group C (those who have undergone mastectomy at the time of scoring) give a severity of 3 or 4, with none scoring their pain as 5.

(Table 2) shows the types of analgesia prescribed throughout the patients’ enrolment on the programme. None of the patients was receiving either opioids or an adjuvant prior to enrolling under Little Hospice Hoima. Only 8 patients out of 67 had pain that was managed with simple analgesia only. Over half required opioids, and nearly half required an adjuvant for neuropathic pain. The majority (69%) of patients who had undergone mastectomy prior to being enrolled were prescribed an adjuvant, whereas fewer than half were taking morphine. In those with purely tumour-related breast pain (Group A), 60% required opioid analgesia, and 40% were receiving amitriptyline.

The seven patients in Group B were analysed separately in order to assess whether there had been any change in their pain following mastectomy. There was no patient that reported consistently worse pain post-operatively. One patient reported pricking pain at 3/5 (previously had been ‘insect biting at 2/5) 3 months post-mastectomy but at 5 months was not taking any analgesia, with a pain score of 0/5. The other cases had similar positive pain outcomes.

(Table 3) shows the other treatment protocols that patients underwent. Barriers to receiving radio-and chemotherapy were most often lack of financial means, lack of carer to accompany the patient to Kampala and lack of radiotherapy services since the machine broke in April 2016. Many patients had been seeking help from traditional healers and herbal medicines prior to seeking attention from health services - often a contributing factor towards delayed presentation (Table 4).

Unfortunately, a large proportion of patients in the study were ‘lost to follow-up’, the majority of whom were in Group A. It makes it difficult therefore to interpret the rest of this data with regards to mortality rates. The patient that self-discharged preferred to continue with herbal medicines as she felt that they were providing some relief. 48% of the patients taking herbal medicine were documented as having died, with a further 37% lost to follow-up.

Finally, files were analysed for evidence of a biopsy having been carried out. Only 29 (43% of all patients) had reported having had a biopsy - this number includes all those patients from Groups B and C who had a mastectomy and it is presumed that the tissue was sent for histology. Out of all those that had a biopsy, only 13 had histology results documented in their files - the remaining 16 verbally reported that the results were ‘positive’ but were unaware of types or staging. Again, barriers to obtaining biopsies included financial constraints, as well as fear and poor health services. A number of patients remained in hospital for many weeks without undergoing biopsy. An example of this was a lady in her forties who presented with lumps extending from the tail of her breast into the axilla. She was kept on the ward for six weeks, without a biopsy being taken, before she absconded in frustration and died a few weeks later at home.

Table 1: The number of patients in each group and how many reported pain on initial clerking (NB: Groups A and B were ‘non-mastectomy’ at point of enrolment). The patients in Group C had undergone mastectomy from 1 week up to 20 years prior to enrolment.

| Group | No | Pain on enrolment (%) |

| A | 46 | 38 (83) |

| B | 7 | 6 (86) |

| C | 14 | 10 (71) |

Table 2: shows the types of analgesia prescribed throughout the patients’ enrolment on the programme. None of the patients was receiving either opioids or an adjuvant prior to enrolling under Little Hospice Hoima.

| Simple (%) | Opioid (%) | Adjuvant (%) | |

| A | 6 (13) | 28 (60) | 19 (40) |

| B | 1 (14) | 6 (86) | 4 (9) |

| C | 1(8) | 5 (38) | 9 (69) |

Table 3: shows the other treatment protocols that patients underwent. Barriers to receiving radio-and chemotherapy were most often lack of financial means, lack of carer to accompany the patient to Kampala and lack of radiotherapy services since the machine broke in April 2016. Many patients had been seeking help from traditional healers and herbal medicines prior to seeking attention from health services - often a contributing factor towards delayed presentation

| Radiotherapy | Chemotherapy | Herbal | |

| A | 1 | 3 | 20 |

| B | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| C | 7 | 11 | 3 |

Table 4: large proportion of patients in the study were ‘lost to follow-up’,.

| RIP | Lost to follow-up | Active | Dis-charge | Self-discharge | |

| A | 19 | 20 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| B | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

DISCUSSION

The results show a high incidence of breast pain in advanced cancer patients. Specifically, there is a predominance of neuropathic pain in both groups. Despite this, there is a much lower proportion of those with neuropathic pain secondary to tumour growth who are receiving adjuvant medication such as amitriptyline, compared to the patients suffering chronic post-mastectomy pain.

Chronic neuropathic pain is a recognised post-operative risk following mastectomy, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The breast tissue is supplied primarily by the 4th to 6th intercostal nerves, but also receives innervation from the long thoracic, thoracodorsal and intercostobrachial nerves. Jung et al. [16], describe four categories of chronic neuropathic pain syndromes following breast cancer surgery: phantom breast pain, intercostobrachial neuralgia, neuroma pain and other nerve injury pain. Damage to the intercostobrachial nerve during surgery is a known risk and can lead to what has commonly been described as ‘post-mastectomy pain syndrome’ (PMPS). This might give rise to pain at the axilla, medial upper arm and the anterior chest wall, although more often causes loss of sensation to these areas, rather than pain. Neuromas account for much of the ‘scar pain’ described by patients and occur when damage to peripheral nerves occurs and neuromas develop in scar tissue. It is therefore suitable that many of the post-mastectomy patients presenting with pain have been commenced on adjuvant medication such as amitriptyline.

Pain as a result of tumour growth is less widely discussed. An article in The Lancet from 1999 discusses the management of cancer pain and describes a number of tumour-related pain syndromes, both nociceptive and neuropathic in origin [17]. The WHO has released guidelines on the classification of neuropathic cancer pain and divides it into nerve compression pain (NCP), nerve injury pain (NIP) and sympathetic maintenance pain (SMP) [11]. It highlights the importance of differentiating between the burning sensation felt with NIP, which tends to be dermatomal in distribution, and the burning pain with SMP, which has an arterial distribution. The treatment for each differs, with SMP often benefitting from a sympathetic block with local anaesthetic. NIP responds best to an adjuvant. NCP may be treated successfully with opioid analgesia, but often only if a corticosteroid is added.

In general, pain had a higher prevalence and tended to be more severe in those patients who did not undergo mastectomy (i.e. tumour-related pain). This is further backed by evidence provided by those that underwent mastectomy whilst on the programme, who reported less pain post-operatively, and some were even able to come off analgesia altogether. This is an important observation, as it highlights the potential benefits of ‘palliative mastectomy’, although usually those who would not benefit from ‘curable mastectomy’ are often too unwell to be considered for surgery.

A significant proportion (40%) of the patients with advanced breast cancer had pursued herbal therapies prior to presenting to health services. This is a large contributory factor towards late presentation of cancer patients. The study also highlights the relative lack of availability of services in Uganda such as chemo- and radiotherapy. Many patients who had undergone mastectomy were unable to receive these therapies following surgery owing to financial constraints (Figure 6).

LIMITATIONS

Many patients were unfortunately lost to follow-up, as their contact phone numbers became unavailable. This had a detrimental effect when considering long-term outcome of patients. The lack of biopsy for over half of the patients being treated clinically as breast cancer also poses a challenge when analysing the data. Although three files were excluded on the basis of negative histology results and poor clinical probability, it is possible that there were other patients included who did not in fact have a malignancy - some of these might account for those ‘lost to follow-up’. Furthermore, there was a lack of data to confirm an improvement following treatment with a specific analgesic drug - although sometimes scores were recorded following commencement of analgesia, they still tended to vary between consultations and therefore became difficult to interpret accurately. However in general, every patient found at least some relief from the analgesia they were commenced on. Finally, both post-chemotherapy and radiotherapy pain are recognised phenomena. Again this study did not allow for accurate assessment of whether these accounted for the pain as many of the patients had undergone both modalities of treatment, as well as mastectomy, prior to presentation at Little Hospice Hoima.

CONCLUSION

In the developed world there is less need for education on how breast tumours themselves might cause pain, as patients tend to present earlier and receive timely management with intent to cure. Public advice regarding breast pain stresses that it is unlikely to be caused by a malignancy, and although it is rarely the first symptom to be noted, it is an important aspect of care for patients with advanced, inoperable and incurable disease in Uganda. More education and awareness of the causes and management of different types of pain experienced in breast cancer, both as a direct result of tumour growth and following mastectomy, is needed.

REFERENCES

5. Chalasani P. Breast Cancer Clinical Presentation. 2017.

6. Breast cancer. Cancer Research. UK.

11. Cancer Pain Relief: with a guide to opioid availability - 2nd Ed. World Health Organization 1996.

14. Smith HS. Opioids and Neuropathic Pain. Pain Physician. 2012; 15: ES93-ES110.

17. Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. The Lancet. 1999; 353: 1695-1700.