Transformative Care for Fibromyalgia and Chronic Pain: Integrating Self-Care Training with Treatment through the Prevention Program to Prevent Chronic Pain, Addiction, and Disability

- 1. Pain Specialist, Minnesota Head and Neck Pain Clinic Professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota, USA

- 2. Medical Director. The Frida Center for Fibromyalgia, USA

Abstract

Chronic pain from fibromyalgia and other pain conditions is the big elephant in the room of health care. It is the top reason to seek care, the 1 cause of disability and addiction, and the primary driver of healthcare utilization, costing more than cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. More than half of the persons seeking care for pain conditions at 1 month still have pain 5 years later despite treatment often due to lack of training patients in reducing the many patient centered risk factors that lead to delayed recovery, chronic pain and in some cases, addiction. This points to the need for is a new model of care– transformative care– which integrates patient self-management training of patients with treatments to help prevent the impact of FBM chronic pain and addiction while helping the health care system recover from it’s devastating escalation in chronic pain and addiction. This paper describes the concepts and practical strategies associated with implementing transformative care using an on-line prevention program (PP) with health coaching (preventionprogram.com). PP integrates risk assessment, self-management training, and telehealth coaching with change in clinical paradigms by the health professional to be more patient-centered.

Keywords

• Transformative Care

• Fibromyalgia

• Chronic pain

• Self-care Training

• Prevention Program

Citation

Fricton J, Liptan G (2025) Transformative Care for Fibromyalgia and Chronic Pain: Integrating Self-Care Training with Treatment through the Prevention Program to Prevent Chronic Pain, Addiction, and Disability. JSM Pain Manag 3(1): 1008.

INTRODUCTION

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic pain condition characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties, affecting approximately 2-8% of the global population, with a higher prevalence in women than in men. Emerging research underscores its significant impact on quality of life, mental health, and productivity. Individuals with fibromyalgia often experience co-morbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances, leading to increased healthcare costs and decreased work performance [1-10]. Furthermore, the complexity of fibromyalgia symptoms poses challenges for diagnosis and treatment, emphasizing the need for a multidimensional approach to management. Symptoms of fibromyalgia are more prevalent in patients with chronic fatigue estimated at least 20% [6]. Due to this lack of objective findings and diagnostic criteria of these disorders, they are often overlooked as a common cause of persistent pain [9,10]. A systematic review by Papatheodorou et al. (2020), examined prevalence rates in various countries, noting that varying methodologies and cultural perceptions of pain often influence reported prevalence with ratios ranging from 7:1 to 9:1 compared to men [11].Longitudinal studies have illustrated the persistent nature of fibromyalgia, revealing that over half of individuals who seek care within the initial months of symptom onset continue to experience significant pain five years later, despite various treatment interventions. For instance, a study by Üstün et al. (2019), found that over 50% of patients reported ongoing pain and functional impairment after five years of management [4]. Furthermore, research indicates that up to 20% of these patients may progress to develop long-term disability due to the chronicity of the condition and its associated symptoms, emphasizing the need for effective early interventions to mitigate long-term outcomes [5,6]. These findings underscore the challenges of treating fibromyalgia and highlight the necessity for continued research into comprehensive management strategies for affected individuals. This delayed recovery is primarily due to the lack of addressing patient-centered risk factors such as poor ergonomics, repetitive strain, inactivity, prolonged sitting, stress, sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, abuse, and many others that increase peripheral and central pain sensitization and lead to chronic pain [4-11]. If usual care fails, clinicians and patients often escalate care to passive higher-risk interventions such as opioids, polypharmacy, surgery, or extensive treatment resulting that may not work well [4-8]. Clinical trials investigating the management of fibromyalgia have consistently demonstrated that passive interventions, such as medication and passive physical therapies, are often no more effective-and sometimes less effective—than active, patient-centered approaches that emphasize self-management strategies [10-15]. A multinational study by Bennett et al. (2017), explored the impact of self-management education for FM across different countries [12]. Research by Zautra et al. (2016), demonstrated that structured self-care educational interventions improved overall health status and reduced FM symptoms [13]. The authors evaluated a community based self-management program that included education about pain management techniques, exercise, and stress reduction, finding enhancements in emotional well-being and pain-related functioning.The authors emphasized that self-care strategies enable patients to take responsibility for managing their health. The study revealed that many patients lacking proper education experienced increased symptom severity and poorer health outcomes. Research indicates that techniques such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), therapeutic exercise, and mindfulness-based stress reduction lead to greater improvements in pain management and overall quality of life by empowering patients to take an active role in their care [11,12]. For example, a systematic review by McBeth et al. (2020), found that active self-care interventions significantly improved physical function and reduced pain levels compared to passive treatments, highlighting the importance of equipping patients with tools to manage their condition effectively [18]. A qualitative study conducted in Israel by Erich et al. (2020), highlighted the importance of patient-centric educational models. This study showcased patients’ perspectives on existing educational resources and revealed a demand for more tailored approaches addressing individual learning styles and needs [14]. Recent trends emphasize the use of digital platforms for self-care education. A controlled trial conducted in Canada by Kziha et al. (2022), examined an online self-management program tailored for fibromyalgia patients, demonstrating significant improvements in participants’ pain and fatigue levels, as well as greater adherence to self-care practices [15]. These findings suggest that a shift towards more engaging, self-directed management strategies may offer better long-term outcomes for those living with fibromyalgia. The incorporation of self-care patient education in the management of fibromyalgia is gaining momentum internationally. While the prevalence of FM highlights the need for effective self-management strategies, studies consistently indicate that comprehensive education programs can empower patients, improve symptom management, and enhance quality of life. Continued research and resource allocation are essential to ensure the widespread availability and efficacy of these educational initiatives across diverse populations.There is need to define a new model of care– transformative care– for fibromyalgia which integrates robust self-management training with health and wellness coaching combined with the best and safest evidence-based treatments [21]. This paper describes the characteristics of FM and the concepts and practical strategies associated with transformative care as implemented through the Prevention Program (PP) (www.preventionprogram.com).

Defining Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic pain syndrome characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, soft tissue tenderness, stiffness, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive difficulties, often referred to as fibro-fog [22-30]. Characteristics of FM that occur in more than 75% of FM people have these symptoms. A variety of associated symptoms occur in less than 25% of FM people and include: irritable bowel, headaches, psychological distress, Raynaud’s phenomena, swelling, paresthesias, and functional disabilities [23,24]. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, which include a history of widespread pain lasting more than three months and the presence of symptom severity scores reflecting fatigue, sleep problems, and cognitive difficulties [22]. In 2016, the ACR updated its criteria to focus on the combination of widespread pain index (WPI) and symptom severity score (SSS), requiring a WPI score of 7 or greater and an SSS score of 5 or greater, or a WPI score between 3-6 and an SSS score of 9 or greater. These criteria assist healthcare providers in making a FM also is characterized by widespread tenderness on palpation at defined locations on the neck, trunk, and extremities. Symptoms of FM can prevalent in the general population ranging from 3.7% to 5 [24-27]. Fibromyalgia is a common systemic rheumatic pain syndrome that consists of widespread pain and tenderness on palpation at definable classic locations on the neck, trunk, and extremities (Table 1).

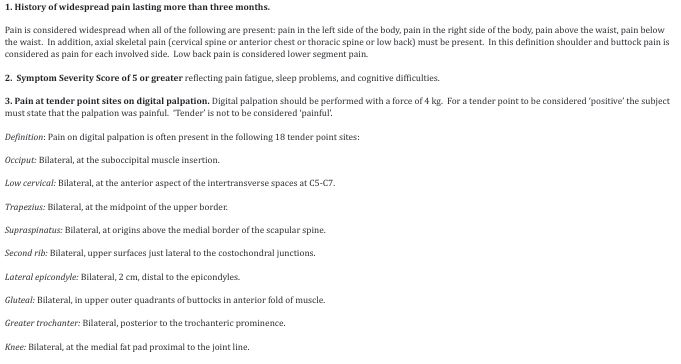

Table 1: Clinical characteristics of Fibromyalgia as defined by the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria. For classification purposes, patients will be said to have fibromyalgia if both criteria of widespread pain and symptom severity are satisfied. Widespread pain must have been present for at least 3 months.

age of onset is artificially high. Therefore, FBM should be suspected in any person presenting with widespread pain since the consequences of prolonged, undiagnosed pain can be considerable.Myofascial pain (MFP) often accompanies fibromyalgia and is characterized by localized muscle pain and tenderness, often associated with identified trigger points in taut bands of muscle [23-25]. Clinically, patients experience aching pain that may radiate to other areas, exacerbated by specific movements or palpation of trigger points. While fibromyalgia is widespread soft tissue pain, myofascial Pain (MFP) is more regional pain such as head, neck, shoulder and back pain. MFP is prevalent in FM people but is often overlooked as a common cause of persistent regional pain in most people with this condition. The clinical characteristics of MFP include localized tenderness in taut bands called trigger points (TrP) with pain in a zone of reference, occasional associated symptoms and the presence of contributing factors (Table 2).

Table 2: Characteristics and scientific efficacy of each component of self-management training.

|

Intervention |

Scientific Basis |

Implementation |

|

Self-management |

Systematic reviews of chronic pain self-management [16-40] |

Training to reduce risk factors and strengthen protective factors |

|

Healthy habits |

Systematic reviews of cognitive-behavioral therapy[16-22] |

Daily habits of exercise, posture, diet, sleep, safety and injury prevention, and others |

|

Daily pauses |

Systematic reviews of mindfulness-based stress reduction[23-26] |

Mindfulness to check in daily on body, lifestyle, thoughts, emotions, purpose, social harmony, and environment |

|

Calming practice |

Systematic reviews of meditation, relaxation, and guided imagery[27-29] |

Relaxation training to relax body and mind and gain insight, understanding, motivation, and compliance |

|

Tele-health coaching |

Systematic reviews of health coaching and social support[32-34] |

Support from health coach, friends and family, reminders, and alerts |

|

Online delivery platform |

Systematic reviews of computer-based and Internet interventions[35-55] |

Computer and smart phone apps that are accessible, personalized, engaging interactive, confidential, and secure |

A TrP is defined as localized deep tenderness in a taut band of skeletal muscle that is responsible for the pain in the zone of reference, and if treated, will resolve the resultant pain.

Mechanisms of Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is characterized by a complex interplay of peripheral, central, and other mechanisms that contribute to its hallmark symptoms of widespread pain, fatigue and fibro-fog [32-34]. Peripheral mechanisms involve altered nociceptive processing, where peripheral nerves may become sensitized due to inflammation or injury, leading to heightened pain perception [33]. Central mechanisms play a significant role, as neuro-imaging studies have shown abnormalities in brain structures responsible for pain modulation, including increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula, suggesting a central sensitization phenomenon where the nervous system amplifies pain signals [20]. Additionally, dysregulation in neurotransmitters such as serotonin and norepinephrine may impact pain perception and contribute to accompanying symptoms like anxiety and depression [19]. Other factors, including genetic predispositions, hormonal imbalances, and environmental stressors, further complicate the clinical picture, highlighting the multifactorial nature of fibromyalgia and underscoring the need for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to management [32].

- Central Sensitization and Biasing mechanisms: Multiple peripheral and central factors may inhibit or facilitate central input through modulatory influence of the brain stem. This may explain the diverse factors that can either exacerbate or alleviate the pain such as stress, repetitive strain, poor posture, relaxation, medications, temperature change, massage, local anesthetic injections, and electrical stimulation.

- Repetitive strain hypotheses: Repetitive strain from tensing muscle habits contribute to localized progressive increases in oxidative metabolism and depleted energy supply (decrease in the levels of ATP, ADP and phosphoryl creatine and abnormal tissue oxygenation). The result is changes in the muscle nociception, particularly with type I muscle fiber types associated with static muscle tone and posture. Tenderness and pain in the muscle are mediated by type III and IV muscle nociceptors which may be activated by locally released noxious substances such as potassium, histamine, kinins, or prostaglandins, causing tenderness. Neurophysiological hypothesis: Tonic muscular hyperactivity may be a normal protective adaptation to pain instead of its cause. Phasic modulation of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons supplied by high-threshold sensory afferents may be involved.

- Peripheral Sensitization: Convergence of multiple afferent inputs from the muscle and other visceral and somatic structures in the lamina I or V of the dorsal horn on the way to the cortex can result in perception of local and referred pain.

Evidence-Based Treatments

Due to the multifaceted nature of fibromyalgia, treatment often requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary transformative care approach that incorporates pharmacological, non-pharmacological therapies and self-management training. Evidence-based treatment strategies for fibromyalgia include;

- Antidepressants. Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) that has been shown to reduce pain and improve functional outcomes in fibromyalgia patients. A meta-analysis found significant improvements in pain relief and overall function when compared to placebo [31]. Milnacipran (Savella) is another SNRI specifically approved for fibromyalgia and has shown efficacy in pain reduction and enhancing quality of life [32].

- Anticonvulsants. Pregabalin (Lyrica) is often used for neuropathic pain and has shown significant efficacy in reducing pain and improving physical functioning in fibromyalgia patients [37]. Studies have shown that Gabapentin may also provide pain relief in fibromyalgia patients [35].

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen and Nonsteroidal Anti Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): While not typically effective on their own for fibromyalgia pain, these medications can be used as adjuncts for symptom management [36].

- Physical Therapy and Chiropractic Treatment. Tailored physical therapy programs emphasizing stretching, strengthening, and aerobic exercises can lead to reductions in pain and improvements in physical function [40,41].

- Acupuncture. Some studies suggest acupuncture may help relieve pain and improve quality of life for individuals with fibromyalgia, though results can vary [39].

Education in Self-Management for Fibromyalgia

Passive treatments alone may not improve fibromyalgia long-term. Thus, transformative care integrates treatments with robust personalized self-management training and support to engage and empower patients [35-41]. Common evidence-based self-care educational interventions include;

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). CBT has been shown to be effective in managing fibromyalgia symptoms, particularly in reducing pain and disability. A systematic review highlighted its benefits in improving pain tolerance and coping strategies [39].

- Exercise. Regular physical activity has been consistently shown to improve pain, function, and quality of life in fibromyalgia patients. A meta analysis concluded that both aerobic exercise and resistance training could provide significant benefits [42].

- Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques. Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) and other relaxation techniques have demonstrated improvements in pain perception and mental health outcomes in fibromyalgia patients [43].

- Yoga. Evidence indicates that yoga can alleviate fibromyalgia symptoms, improve sleep, and enhance mental well-being [41].

- Health Education programs for Fibromyalgia. For example, an excellent program called “Amigos de Fibro” (Fibro Friends) and other resources are available at services [45,46].

Transformative Care: Integrating Training with Treatment

When transformative care with robust patient centered self-management strategies is added to evidence based treatments for FM and MFP pain conditions as part of routine care, chronic pain, disability, addiction, and it’s consequences can be prevented. Furthermore, transformative care can improve long-term outcomes dramatically while also reducing the patient’s dependency on the health care system. Transformative care can help transform both the patient’s life as well as improve the health care system. For this reason, health care leaders including the Institute of Medicine, the National Pain Strategy, and the Institute for Clinical System Integration have recommended integrating self-management strategies that engage, educate and empower people routinely in clinical practice to prevent chronic pain and addiction [7,8]. However, there are many barriers for health professionals to implement transformative care. The lack of reimbursement, time burden, and inadequate training skills coupled with the lack of care coordination, fragmented care, poor communication, and conflicting treatments each interfere with patient-centered transformative approaches in clinical practice. The Prevention Program (PP) (preventionprogram. com) was developed with funding from the National Institutes of Health to improve the implementation of self-management as part of routine care [43-45]. The PP personalized activated care and training designed to overcome some of these barriers and support health care providers in improving long-term outcomes of those with pain disorders. It is based on the Chronic Care Model (CCM) has documented evidence of its efficacy for chronic conditions in more than 100 healthcare organizations [47-59]. PP provides health care professionals with a simple solution to integrate multiple evidence-based self-management training and health coaching with their treatments using an on-line platform (Table 2). Systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials of self-management with mindfulness-based stress reduction, CBT, exercise, lifestyle changes show significant improvement with chronic pain [60-74]. In addition, reviews of social support and health coaching show that they can improve functional recovery from chronic pain [75-87], in addition, web based solution have shown significant efficacy due to its engagement of patients [88-100]. By integrating all of these strategies within PP, it can better engage, empower, and educate patients in learning the skills of long-term self-management for chronic pain.

More than Patient Education

Prevention programs are more than patient educational tools but rather a well defined therapeutic program with a goal of helping people understand the big picture of chronic pain, and how risk factors and protective factors in each realm of our lives can be changed with self-management strategies to relieve and prevent their chronic MFP and FM. PP includes online tools for risk assessment, therapeutic CBT training, and relationship-based health coaching that are easily integrated into a person’s daily life and personalized to their individual characteristics. The PP program also leverages the benefits of a support team including a social network for family, health care providers, and a health coach to enhance engagement in self-care and long-term success. The PP also tracks patient understanding, adherence, health care, and outcomes with a dashboard to demonstrate to the participant and healthcare provider change over time and send alerts when problems exist. Furthermore, since the PP program is designed to be responsive to both smart phones and computers, it can be implemented anywhere, at any time, to easily integrate into a person’s life. It is also secure, confidential, transferable, and scalable to be a cost effective addition to a benefit package for employers, health plans, health systems, and health professionals.

Risk Assessment

The on-line program includes a series of brief psychometrically derived assessments to evaluate pain location, severity and health care use; self-management engagement; readiness to change; and risk assessments in the seven realms of a person’s life including the mind, body, emotions, spirit, lifestyle, social relationships, and physical environment [50-53]. PP assesses the causes for chronic pain and delayed recovery and not only the symptoms. The assessment identifies protective factors in each of those realms that a patient can build on including exercise, posture, balanced lifestyles, good sleep, healthy nutrition, safety practices, mindfulness, meditation, and many more (Table 3).

Table 3: The on-line self-management prevention program includes training tools to help understand pain and how each of the 7 realms of our lives can help us relieve and prevent chronic pain.

|

8 Training Tools |

Protective Factors |

Risk Factors |

|

1. Understanding pain and its self- management |

Understand the big picture of pain, protective factors, treatments, self-management |

The conditions, the risk factors, and the cycles that cause pain to persist |

|

2. Body is our physical structures and their function |

Stretching, strengthening, fitness, conditioning, balanced relaxed posture and reducing strain |

Tight weak muscles and joints, poor conditioning, tense unbalanced postures, repetitive strain |

|

3. Lifestyle is our daily behaviors |

Pain-free diet, restful sleep, steady active pacing, and limiting substance use |

Poor diet, poor sleep, sedentary or hurrying/rushed, and substance misuse |

|

4. Mind is our thoughts & attitudes |

Optimism, self-efficacy, realistic expectations, coping, resilience, |

Pessimism, low self-efficacy, unrealistic expectations, passive coping, low resilience |

|

5. Emotions are our feelings |

Joy, happiness, calm, courage, gratitude, forgiveness, empathy, self-acceptance |

Depression, sadness, anxiety, fear, anger, frustration, guilt, shame |

|

6. Spirit is our purpose & energy |

Purpose, energy, self-compassion, hopes, dreams, grit and determination |

Stress, burnout, cynicism, doubt, feeling helpless and hopeless |

|

7. Social life is our relationships |

Love, belonging, social support, work well-being, releasing social stress |

Isolation, loneliness, low social support, work stress, conflict, abuse, social stressors |

|

8. Environment is the world we interact with |

Safe living, safe driving, clean, infection-free, pollution-free, and risk-free health care |

Risky unsafe living, risky driving, unclean, infection-prone, pollution, toxicity, unsafe risky health care |

Personalized Self-Care Education

Based on the assessments, personalized experiential lessons are presented to train participants in reducing risk factors for delayed recovery and promoting protective factors that encourage healing. The program consists of eight on-line modules or tools designed to be completed during 3 to 6 months of support. Each module includes several less than ten minute interactive lessons to review. They begin with understanding the big picture of the condition, how it can be improved by the balance between risk and protective factors in each realm. Then, each subsequent training tool focuses on the seven realms including the mind, body, emotions, spirit, lifestyle, social life, and environment and what changes can be made to improve the pain. The program includes guides for quick review, action plans for each realm, and worksheets to understand what to do. The action plan for each lesson includes 3 components: Healthy HABITS, daily PAUSEs, and CALMING practice. Overcoming barriers to change is also addressed to help completing these action plans.

- Healthy HABITs means taking dedicated time each day to work on enhancing protective factors in order to decrease risk factors. This includes healthy habits of exercise, sleep, diet, healthy substance use, maintain activity level, optimism, positive emotions and others.

- Taking PAUSEs promotes mindfulness by taking a brief time-out to check-in and notice how you are doing right now in a non-judgmental way. This is essential to living a life in the present and being mindful of protective factors to enhance health and well-being.

- CALMING practice promotes meditation by spending a few minutes each day doing a brief relaxation technique allows many benefits. These include meditation to calm the mind, relaxing the muscles and nerves, contemplation about your life, and reflection on how you will move forward.

Health and Wellness Coaching(HWC)

HWCs are trained and certified health professionals who develop a coaching relationship with patient to assist client’s in identifying their own goals and priorities, review assessments, and provide guidance to patients in establishing healing plans, and facilitating their knowledge, understanding, and skills necessary for successful self-management of chronic conditions [79 87]. Trained and nationally board certified health and wellness coaches can be provided either through the PP program or through a health plan, since many health plans are now employing health coaches. The process incorporates the needs, goals and life experiences of the patient to guide them in successful care for their condition. Many health coaches work with patients by phone or secure video-conferencing using telemedicine portals or in-person. The coach will assist the patient through the process of care by actively working towards better health by evoking awareness and values, increasing recognition of strengths, creating a route to accountability, offering encouragement, and providing education and resources. Primary responsibilities include; 1) assist in setting goals to achieve in basic self-management for their condition, 2) enhance understanding and engagement with self assessment and self-management to identify and reduce risk and boost protective factors associated with their condition, 3) encourage patients in following up with health care provider to achieve quality patient-centered care and successful outcomes, 4) explain how to navigate on-line programs, education materials, and daily logs to document triggers, risk factors, protective factors and barriers to success, 5) answer appropriate questions that many patients still have about their problem and how it will be addressed with transformative care plan, or connect patient with a higher level of provider for that information when necessary.

Shifting Paradigms

The Institute of Medicine’s 2011 monograph emphasizes the need to transform our current passive model of doctor-centered care into one that is patient centered.1 The document states, Health care provider organizations should take the lead in developing educational approaches for people with pain and their families that promote and enable self-management. The clinical application of transformative care involves not only identifying and reducing risk factors and improving protective factors, it involves shifting both the patient’s and health professional’s clinical paradigms so that patients understand their important role in care. Since patients often expect to have a passive role in care, these new paradigms need to be conveyed to the patient as part of the evaluation (Table 4).

Table 4: Successful self-management requires a shift in clinical paradigms implicit in person-centered care.

|

New paradigm |

Description and presenting concept |

|

Understand the whole person |

You need to identify all conditions, risk factors, and protective factors in the 7 realms of your life to shift the balance from illness to health. Are you willing to do self-assessments? |

|

Each person is complex |

Multiple conditions and interrelated contributing factors may initiate, result from, increase risk, or decrease risk of illness. Are you willing to address each? |

|

Self-responsibility is key to recovery |

You have more influence on the problem than any treatment provided. Will you take ownership and control of the condition? |

|

Self-care |

You will need to make daily changes in order to improve your condition. Are you willing to take the time to do this? |

|

Education and training |

You need to learn how to make the lifestyle changes that will improve the condition long-term. Are you willing to learn it? |

|

Long-term change |

Change occurs gradually over time and it may take months to have a large impact. Are you patient and persistence to see success? |

|

Personal motivation |

It takes a commitment to a daily action plan to have success. Are you motivated to do so? |

|

Social support |

You may need help from a health coach, family, and friends to make these lifestyle changes. Are you open to receiving help? |

|

Change process |

Change and improvement will occur in small steps incrementally over time. Will you notice the gradual change? |

|

Fluctuation of progress |

Expect ups and downs during the recovery process. Are your resilient enough to overcome the ups and downs? |

Embracing patient-centered health care paradigms such as self-responsibility, education, personal motivation, self-efficacy, social support, strong provider-patient relationships, and long-term change will shift the balance of care from one of a passive, dependent patient to an empowered, engaged, and educated patient [50-53]. Ultimately, this paradigm shift will not only improve the quality of care, enhance pain and functional outcomes, but also significantly reduce health care costs.

Engaging, Educating, and Empowering the Patient

The key to the success of any self-management training program, particularly if it is on-line is the ability to engage the participant in making needed changes to improve their pain. The PP program maximizes engagement;

- Accessible by any devices. On-line training needs to be delivered through a responsive website that can be accessed by smart phone, tablet, or computer.

- A Pact between Health Professionals and Patients. A pact between the provider and patient to implement transformative care. The provider will follow-up the patient and use the dashboard to track and reinforce progress.

- Supported by Tele-Health Coach (THC). THCs are well-trained and certified health professionals who can support success of a participant’s self-management training The coach helps the participant understand their goals, risk factors, protective factors, barriers, and individual skills and talents to help them through the program.

- Support by Family and Friends. Having friend or family team member who can support participants and encourage them along their journey. Each participant can sign up any teammate at the beginning or at any time using the team link of the dashboard.

- Understanding the whole person. In contrast to the limited scope or fragmentation of many pain training and treatment programs, the program is intended to help people evaluate risk and protective factors in all realms of their life including the body, mind, lifestyle, emotions, spirit, social life, and environment.

- Engaging characters. Several animated characters are designed to assist the participant in learning. Professor Payne is a distinguished professor and pain specialist who presents the lectures but also tells stories of the many patients he has helped over the years. Action Annie is a perky plain-speaking trainer whose main job is to help the participant implement their action plan within their lifestyle. Calming Kate is an experienced health professional who teaches calming practice using techniques from both mindfulness-based stress reduction and indirect hypnosis for pain control. She uses a calm voice, enlightening dialogue, and guided imagery. Barrier Bob is a no-nonsense barrier buster who helps participants identify and change barriers that may be confronted on the way to changing a person’s health and life.

- Interactive content. To engage the patient in learning, there are various interactive playful components includes bursting the benefit bubbles, breaking barrier bricks, interesting stories of people, and acronyms of phrases to help patients remember the concepts.

- Simple Action Plan. An action plan that is generated for each module includes 3 components: Healthy HABITS, daily PAUSEs, and CALMING practice. Overcoming barriers are discussing to help completing the action plans.

- Dashboard. A dashboard based on the pain assessments is provided to track participant engagement in the program, pain, functional status, action plan status, and risk factor assessment.

- Mobile Phone App. Phone apps that are connected to the dashboard can also be implemented to track steps, blood pressure, pulse, weight, sleep, stress, and other biometrics.

- Reminders. The program sends out reminders to the participant to reinforce success and encourage completion of the program.

- Worksheets. The program also has many resources that provide written documentation for each lesson including an action plan summary, a daily log, and worksheets for each lesson.

Implementing Routine Care Self-Management

To implement self-management, the health professional needs to ask their patient; I am happy to provide treatment for your condition, but it is more successful long-term if we also train you to reduce the causes of the pain. Are you interested? In the current study of the PP program, when health professionals ask this question, nearly all patients consent to participate in the on-line training program and more importantly, begin making the needed personal lifestyle changes to improve their pain condition long-term. Health plans are poised to reimburse risk assessment, therapeutic training, and health coaching as part of transformative care. The reimbursement of the PP pain program as a service is a key to its success for both health care providers and health plans. Without transparent costs for implementing the program, it will be considered under-valued resulting in lower patient and health provider engagement. When the participant sees value of the program and makes a decision to participate based on this value, engagement and success is improved. Thus, the PP program services are integrated into the care plan instead of being offered as a stand-alone service offered by health plans and employers.

The Health Care Provider as an Agent of Transformative Change

As part of all health care, the health care provider needs to recognize that he/she is part of the patient’s system of health and/or illness. Treatment in some cases, such as dependency of medications, addiction to surgery, secondary gain from seeking care, and rebound pain from drugs, can be part of the patient’s cycle of problems. If clinicians understand their integral role in cycle between health and illness, they can be part of the solution and help initiate change. To do this, clinicians need to enter the experiential world of the patient and alter it. Clinicians need to help reconstruct a person’s world into one of wellness and not illness and help them access their own resources to make personal change. They need to facilitate patients in achieving the deepest most permanent order of change- a third order change the alters their epistemological understanding of health and well-being– and allow them to see their world completely differently.

SIGNIFICANCE

The focus on preventing chronic pain and its impact can have a significant impact on society, professionals in the field, and healthcare costs if it is implemented in routine healthcare for chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia is a common condition causing chronic pain and are a common for seeking care, causing limited function and disability, and one of the highest driver of health care costs, costing more than cancer, heart disease, and diabetes combined, not to mention incalculable personal impact. There were also several areas of focus for health professionals regarding implementing transformative care.Implementing a transformative model of health care that integrates robust self-management training with evidence-based pain treatments through a team approach to care. A transformative care model that includes self management training with evidence-based treatments can improve the outcomes of early fibromyalgia management while reducing the patient’s dependency on the health care system and health care costs. Understanding the whole person with chronic pain by understanding their risk and protective factors. The unaddressed risk factors may be reasons that a biomedical treatment may fail. Thus, a shift in patient-centered clinical paradigms implicit in the clinician-patient relationship will be the key to success.The Prevention Program (PP) (preventionprogram. com) is one such program that can assist in implementing transformative care.50-53 it includes online tools for risk assessment, therapeutic CBT training to reduce risk factors and enhance protective factors, and telephonic health coaching that are easily employed by health professionals, integrated into a person’s daily life, and personalized to their individual characteristics. The PP program also leverages the benefits of a support team including a social network for family, health care providers, and a telehealth coach to enhance motivation, understanding, compliance and success.The PP was developed with funding from National Institutes of Health with three goals including: a) Expanding research and development on preventing chronic pain with the development of the Pain Prevention Research Network as well as developing strategies and tools that health professionals can use to improve their prevention and early management of chronic pain conditions. b) Expanding education of both patients and health professionals on how to prevent chronic pain using a transformative care model is available at www.coursera. org/learn/chronic-pain and c) Advocacy to increase awareness and provide tools to health professionals, health plans, businesses, government agencies, and communities to improve their efforts in preventing chronic pain. By accomplishing these 3 goals, we will address the Institute for Health Care Improvement’s triple aim as it applies to pain conditions to improve the patient’s experience of care, enhance the health of the patient, and controlling the cost of health care.

REFERENCES

- Bae SC. Prevalence and Incidence of Fibromyalgia: A systematic re- view. J Pain Res. 2021; 14: 2237-2246.

- Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: A clinical review. JAMA. 2014; 311: 1547-1555.

- Institute of Medicine (US) committee on advancing pain research, care, and education. Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

- Üstün BT. Fibromyalgia in the World Health Organization’s ICD-11: A Global Perspective. Pain. 2019; 160: 1364-1371.

- Bennett RM. The Long-term Prognosis of Fibromyalgia: A LongitudinalStudy. Pain Med. 2018; 19: 730-735.

- Gureje O. The Global Burden of Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review.Pain. 2018; 159: 200-209

- National Pain Strategy

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guidelines for ChronicPain.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL, et al. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016; 46: 319-329.

- Walitt B, Fitzcharles MA, Shir Y. Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Update. The J Rheumatol. 2015; 42: 697-706.

- Papatheodorou A. Global patterns of chronic pain prevalence in thegeneral population: A systematic review. Pain. 2020; 161: 1059-1069.

- Bennett RM. The effectiveness of self-management education in fibromyalgia: A multinational, multi-center study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2017; 18: 1-12.

- Zautra AJ. Resilience in pain management: A brief overview of therole of self-care education. Pain. 2016; 157: 1693-1705.

- Erich EM. Patient perspectives on educational programs for fibromyalgia: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Res. 2020; 20, 1-10.

- Kziha J. The impact of an online self-management intervention on fibromyalgia symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rheumatol. 2022; 41: 1471-1480.

- Bennett RM. Patient-Centered Approaches in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia: Outcome Comparisons. Pain Med. 2019; 20: 300-310.

- Coyle D. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review. Complementary Therap Med. 2019; 47: 102199.

- McBeth J. Active Versus Passive Interventions for Fibromyalgia: ASystematic Review. The Clin J Pain. 2020; 36: 674-682.

- Bair MJ. The Role of Psychological Factors in Fibromyalgia: A Clinical Review. Pain Med. 2018; 19: 816-822.

- Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014; 311: 1547-1555.

- Fricton J Clavel A, Weisberg M. Transformative Care for Chronic Pain. Pain Week J. 2016; 44-57.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010; 62: 600-610.

- Arnold LM, Stanford SB, Welge JA, Crofford LJ, Hudson JI. Measures of fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Sleep Scale, and Short Form-36 (SF- 36). Arthritis Care Res. 2006; 57: S85-S98.

- Arnold LM, Crofford LJ, Mease PJ, Burgess SM, Palmer SC, Abetz L, et al. Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Educ Couns. 2008; 73: 114-120.

- Glass JM. Cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: New trends and future directions. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006; 8: 425-429.

- Moldofsky H. The significance, assessment, and management of nonrestorative sleep in fibromyalgia syndrome. CNS Spectr. 2008; 13: 22-26.

- Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia and related conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90: 680-692.

- Travell JG, Simons DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Volume 1: Upper Half of Body. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 1998

- International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of Chronic Pain. In Pain: Clinical Updates. 2011; 19.

- Schmid AB. Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Systematic review of non-invasive treatment. Physical Ther Rev. 2019; 24: 90-98.

- Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Ware AE, Swindle RW. The impact of fibromyalgia on quality of life. J Genetic Disorders Genetic Rep. 2016; 5.

- Mcyc P. The Role of Genetics and Neurobiological Mechanisms in Fibromyalgia: Implications for Treatment. Front Mol Biosci. 2020; 7: 113-130.

- Schmidt WJ. Peripheral and Central Mechanisms of Pain in Fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2018; 37: 2161-2169.

- Yunus MB. Central sensitivity syndromes: A new paradigm and group nosology for fibromyalgia and overlapping conditions, and the related issue of disease versus illness. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37: 339-352.

- Kelley JM, Kraft JA, Eriksen J. Gabapentin for the treatment of neuropathic pain in the fibromyalgia population.” Pain Physician. 2020; 23: E109-E114.

- Lynn J, Goldstein MK, Vasilenko P. The effectiveness of analgesics in fibromyalgia treatment. Am J Managed Care. 2019; 25: e308-e316.

- Woolf CJ, Kwan H, Carr D. B. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia: An evidence-based review. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2021; 51: 746-754.

- Zhang Q, Zhou L, Zhang S. Milnacipran and fibromyalgia: An analysis of evidence. Pain Physician. 2018; 21: 473-482.

- Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, et al. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Pain. 2018; 19: 455-474.

- Macfarlane GJ, Beasley M, Jones GT. Role of physical activity in themanagement of fibromyalgia. Rheumatology. 2020; 59: 554-558.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta- analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2013; 29: 450-460.

- Häuser W, Fitzcharles MA, Schatman ME. Round Table on Fibromyalgia I: The clinical significance of exercise in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2016; 17: 923-930.

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017; 51: 199-213.

- Thieme K, Martini C, Margraf J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for fibromyalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical J Pain. 2016; 32: 1183-1194.

- Antunes MD, Schmitt ACB, Pasqual Marques A. Amigos de Fibro (Fibro Friends): Validation of an e-book to promote health in fibromyalgia. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2023; 24: e41.

- Fibromyalgia resources.

- Fricton J, Anderson K, Clavel A, Fricton R, Hathaway K, Kang W, et al. Preventing Chronic Pain: A human systems approach-results from a massive open online course. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015; 4: 23-32.

- Fricton J. The need for preventing chronic pain: The “big elephant in the room” of healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015; 4: 6-7.

- Fricton, JR, Gupta A, Weisberg MB, Clavel A. Can we Prevent Chronic Pain? Practical Pain Management. 2015; 15

- Fricton J, Lawson K, Gerwin R. Pain Prevention Program: Background and outcomes to prevent chronic pain, addiction and disability with transformative care. Adv Prev Med Health Care. 2024; 7: 1061.

- Fricton J, Lawson K, Torkelson C, Monsein M. Implementation of Prevention Programs in Routine Healthcare. Open Scientific J Health Care Med. 2025.

- Fricton J, Lawson K, Gerwin R, Shueb S. Preventing Chronic Pain: Solutions to a Public Health Crisis. IgMin Res. 2025; 3: 038-051.

- Glasgow RE, Funnell MM, Bonomi AE, Davis C, Beckham V, Wagner EH. Self-management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Ann Behav Med. 2002; 24: 80-87.

- Battersby M, Von Korff M, Schaefer J, Davis C, Ludman E, Greene SM, et al. Twelve evidence-based principles for implementing self- management support in primary care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010; 36: 561-570.

- Glasgow RE, Davis CL, Funnell MM, Beck A. Implementing practical interventions to support chronic illness self-management. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003; 29: 563-574.

- Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, Keeler EB. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2005; 11: 478-488.

- Gee PM, Greenwood DA, Paterniti DA, Ward D, Miller LM. The eHealth Enhanced Chronic Care Model: A theory derivation approach. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17: e86.

- Gammon D, Berntsen GK, Koricho AT, Sygna K, Ruland C. The chronic care model and technological research and innovation: A scoping review at the crossroads. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17: e25.

- Hamine S, Gerth-Guyette E, Faulx D, Green BB, Ginsburg AS. Impact of mHealth chronic disease management on treatment adherence and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17: e52.

- Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta- analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999; 80: 1-13.

- Harris P, Loveman E, Clegg A, Easton S, Berry N. Systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of headaches and migraines in adults. Br J Pain. 2015; 9: 213-224.

- Gordon R, Bloxham S. A systematic review of the effects of exercise and physical activity on non-specific chronic low back pain. Healthcare. 2016; 4: 22.

- Tang NK, Lereya ST, Boulton H, Miller MA, Wolke D, Cappuccio FP. Nonpharmacological treatments of insomnia for long-term painful conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient- reported outcomes in randomized controlled trials. Sleep. 2015; 38: 1751-1764.

- Marley J, Tully MA, Porter-Armstrong A, Bunting B, O’Hanlon J, McDonough SM. A systematic review of interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain--protocol. Syst Rev. 2014; 3: 106.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta- analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2013; 29: 450-460.

- Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: Strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142: 776-785.

- Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review of the evidence. J Altern Complement Med. 2011; 17: 83-93.

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, et al. Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017; 51: 199-213.

- Rosenzweig S, Greeson JM, Reibel DK, Green JS, Jasser SA, BeasleyD. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J Psychosom Res. 2010; 68: 29-36.

- Garmon B, Philbrick J, Becker D, Schorling J, Padrick M, Goodman M, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain: A systematic review. J Pain Management. 2014; 7: 23-36.

- Galante J, Galante I, Bekkers MJ, Gallacher J. Effect of kindness-based meditation on health and well-being: A systematic review and meta- analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014; 82: 1101-1114.

- Kwekkeboom KL, Gretarsdottir E. Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006; 38: 269-277.

- Bailey KM, Carleton RN, Vlaeyen JW, Asmundson GJ. Treatments addressing pain-related fear and anxiety in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A preliminary review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2010; 39: 46-63.

- Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KMG, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance- based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2011; 152: 533-542.

- Campbell P, Wynne-Jones G, Dunn KM. The influence of informal social support on risk and prognosis in spinal pain: A systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2011; 15: 444.e1-14.

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, Smeets RJ, Ostelo RW, Guzman J, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015; 350: h444.

- Holden J, Davidson M, O’Halloran PD. Health coaching for low back pain: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract. 2014; 68: 950-962.

- Garg S, Garg D, Turin TC, Chowdhury MF. Web-Based Interventions for Chronic Back Pain: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2016; 18: e139.

- Bennett HD, Coleman EA, Parry C, Bodenheimer T, Chen EH. Health coaching for patients with chronic illness. Fam Pract Manag. 2010; 17: 24-29.

- Foster G, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self- management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; 4: CD005108.

- Gensichen J, von Korff M, Peitz M, Muth C, Beyer M, Güthlin C, et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: A cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151: 369-378.

- Vale MJ, Jelinek MV, Best JD, Dart AM, Grigg LE, Hare DL, et al. Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH): A multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163: 2775-2783.

- Gary TL, Bone LR, Hill MN, Levine DM, McGuire M, Saudek C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of nurse case manager and community health worker interventions on risk factors for diabetes- related complications in urban African Americans. Prev Med. 2003; 37: 23-32.

- Holden J, Davidson M, O’Halloran PD. Health coaching for low back pain: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract. 2014; 68: 950-962.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006; 166: 1822-1828.

- Foster G, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self- management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; 4: CD005108.

- Gensichen J, von Korff M, Peitz M, Muth C, Beyer M, Güthlin C, et al. Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices: A cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 151: 369-378.

- Macea DD, Gajos K, Daglia Calil YA, Fregni F. The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2010; 11: 917-929.

- Bender JL, Radhakrishnan A, Diorio C, Englesakis M, Jadad AR. Can pain be managed through the Internet? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain. 2011; 152: 1740-1750.

- Gratzer D, Khalid-Khan F. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of psychiatric illness. CMAJ. 2016; 188: 263- 272.

- Eaton LH, Doorenbos AZ, Schmitz KL, Carpenter KM, McGregor BA. Establishing treatment fidelity in a web-based behavioral intervention study. Nurs Res. 2011; 60: 430-435.

- Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Slaughter R, McGhee EM. The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004; 6: e40.

- Paul CL, Carey ML, Sanson-Fisher RW, Houlcroft LE, Turon HE. The impact of web-based approaches on psychosocial health in chronic physical and mental health conditions. Health Educ Res. 2013; 28: 450-471.

- Lau PW, Lau EY, Wong del P, Ransdell L. A systematic review of information and communication technology-based interventions for promoting physical activity behavior change in children and adolescents. J Med Internet Res. 2011; 13: e48.

- Macea DD, Gajos K, Daglia Calil YA, Fregni F. The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2010; 11: 917-929.

- Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. J Public Health Dent. 2011; 71: S20-33.

- Fry JP, Neff RA. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2009; 11: e16.

- Turner JA, Holtzman S, Mancl L. Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2007; 127: 276-286.

- Fricton JR, Nelson A, Monsein M. IMPATH: Microcomputer assessment of behavioral and psychosocial factors in craniomandibular disorders. Cranio. 1987; 5: 372-381.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) Triple Aim. 2016.