Peritoneal Dialysis: A Home-Based Therapy Option with Improving Outcomes in Older As Well As Younger Patients

- 1. Department of Renal Medicine, Alfred Health, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

- 2. Department of Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the quality, effectiveness, and sustainability of peritoneal dialysis as a home-based dialysis care option in older patients as well as younger patients after initiation of a nurse led Home before Hospital model of care.

Methods: Because peritoneal dialysis is reputedly less effective for older patients, especially those with comorbidities, clinical data (demographics, peritoneal dialysis modality, complications, reasons for technique failure / discontinuation of peritoneal dialysis and other clinical and outcome measures) was collected over 8 years until December 2019 in a cohort of 317 patients (324 episodes of care) and compared between two age group categories (< 60 years (younger (n= 149)) and > 60 years (older (n=168)) both descriptively and analytically.

Results: Diabetes (as a diagnosis or a comorbid condition (n=134) was more common in the older group (p<.007) as was death (n=76) as an outcome (p<.001). Progression to transplantation (n=77) was more likely in the younger (p<.001) but the reasons for transfer to hemodialysis (n=59) was not different between the groups including peritonitis (n=16) or membrane failure (n=5). The technique failure rate when censored for death favored the older group (HR=0.74 (CI 95% (0.44 - 1.23)) but not significantly so (p=.246) and the death-censored technique survival rate in the older group exceeded 75% at 3 years.

Conclusion: Using a nurse-led model of care, an extremely high level of transition to a sustainable and successful home-based therapy (centered on peritoneal dialysis) can be achieved in older as well as younger patients.

Keywords

• Home-based therapy

• Elderly

• Peritoneal dialysis

• Model of care

Citation

Ellis J, Tregaskis P, Manefield K, Buena T, Ng Y, et al. (2020) Peritoneal Dialysis: A Home-Based Therapy Option with Improving Outcomes in Older As Well As Younger Patients. JSM Renal Med 3(1): 1014.

ABBREVIATIONS

PD: Peritoneal Dialysis; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; APD: Automated Peritoneal Dialysis; CAPD: Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis

INTRODUCTION

World-wide the population is aging. In Australasia for example, the population >=65 years of age is increasing rapidly and has doubled from 9.3% in 1950 to 17.5% in 2015 [1]. Paralleling the ageing population is an increasing prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) [2,3], which is very common amongst the elderly [4,5]. The Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle AusDiab population study [6] indicated that 1 in 3 of individuals >65 years of age have an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m² (Stage 3 CKD) [7] and in the United States 47% of individuals > 70 years of age have been estimated to have CKD [8]. Furthermore, in Western societies [1,9,10], more than half of the patients commencing dialysis are > 65 years of age, and of the prevalent Australasian dialysis population nearly 40% are aged over 65 [10].

Because static mortality rates [3], quality of life issues [11,12] deteriorating functional status [13], high hospitalisation rates and outcomes have been generally considered to be poor in the elderly (especially those with multiple comorbidities and frailty) questions have continued to be raised about the justification of expensive renal replacement for these patients especially when dialysis may actually worsen outcomes. [13,14] The financial burden of CKD (especially end-stage CKD) is also a major issue for health systems [15,16]. In the US; of the 100 billion dollars annual expenditure on CKD, 34 billion is spent on maintenance dialysis [17], where 90% of the current dialysis populations (~ 500,000 individuals) are receiving maintenance in-center hemodialysis. In patients choosing dialysis as an option, encouraging home based therapies, especially peritoneal dialysis [18] is one way of reducing costs and is certainly significantly cheaper than in center hemodialysis in most jurisdictions [19-22].

There is steadily accumulating evidence that clinical outcomes for patients treated with peritoneal dialysis are equivalent [23-27] or perhaps even better than for patients treated with conventional in-center hemodialysis [27,28]. Facilitating and supporting a home-based therapy, may certainly help patients ‘cope with the challenges’ of ESKD care [18] and such facilitation also acknowledges that a home-based care such as peritoneal dialysis is often the preferred dialysis option for many patients including the elderly [29-34].

Advantages of peritoneal dialysis (PD) as renal replacement therapy have been shown in younger patients [24,35] and include the provision of an excellent bridge to kidney transplantation [36,37]. The demonstration of benefits in older patients [38], is not so well or consistently established (especially in patients with frailty [39,40] or high co-morbidity burden [35] such as diabetes [41]) although the theoretical and reported advantages still appear numerous. [14,39,42-44]. Preservation of residual kidney function (a feature of peritoneal dialysis [34,45]) in patients commencing dialysis has been associated with improved early [46,47] patient survival and possibly longer term survival [48] although mechanistically the relationship between mortality and residual kidney function remains not well understood [49-52].

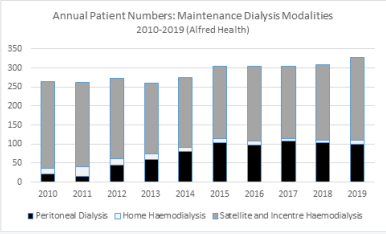

We previously (2012) implemented a re-design project specifically to facilitate home-based therapies with a major focus on peritoneal dialysis at our institution. The project “Home before Hospital” embraced a whole of system change with a focus on early nurse-led education both prior to and post initiation of therapy and ensuring that a home before hospital philosophy underpinned all approaches to dialysis care including nurse-led continuing support after commencement of the therapy. Nearly the entire uptake of home therapies (incident home therapy rate now >50% and prevalent home therapy increasing from 15 % to >35%) was in peritoneal dialysis (Figure 1)).

Figure 1 Numbers of end stage kidney disease patients at Alfred Health receiving maintenance dialysis (by modality) at end of each calendar year (2010-2019). Home before Hospital re-design project from 2012 associated with increase in home therapy patients: > 35% of patients between 2015 and 2019 were receiving a home-based therapy (peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis) predominantly peritoneal dialysis.

The present study therefore aims to not only evaluate the quality, effectiveness, and sustainability of peritoneal dialysis as a home-based dialysis care option but because peritoneal dialysis is reputedly less effective for older patients (35, 39-41), especially those with comorbidities and frailty, to review specifically outcomes in older patients compared to younger patients.

STUDY DESIGN, PATIENTS AND METHODS

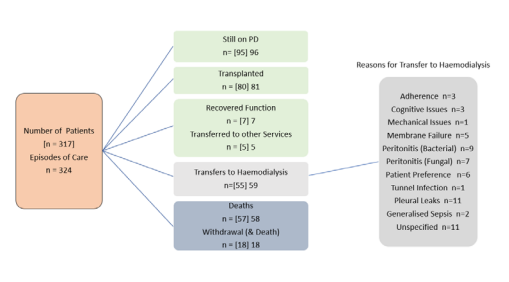

All patients commenced on maintenance peritoneal dialysis at Alfred Health from December 2011 after initiation of a Home before Hospital model of care have had key clinical data collected prospectively (demographics, peritoneal dialysis modality, complications, reasons for technique failure / discontinuation of peritoneal dialysis and other clinical and outcome measures). The cohort includes 317 patients (324 episodes of care) up until the end of 2019. The details of the patient cohort and progression of care on peritoneal dialysis are shown in Figure 2

Figure 2 Outline of Progression of Care for all peritoneal dialysis patients and episodes of care including summary of reasons for those transferring to hemodialysis.

and Table 1

|

Table 1: Peritoneal Dialysis Population Demographics. |

||

|

Parameter |

Characteristics |

|

|

Patient Cohort (n=317) |

Mean age (+/- SD) |

58.4 (+/- 15.5) years |

|

Gender [Male %] |

M: 206 F: 111 [65.1 %] |

|

|

Modality [APD %] |

APD: 290 CAPD :27 [91.5 %] |

|

|

Episodes of Care (n=324) |

Mean age (+/- SD) |

58.4 +/- 15.5 years |

|

Gender [Male %] |

M: 211 F: 113 [65.3 %] |

|

|

Modality [APD %] |

APD: 297 CAPD: 27 [91.7 %] |

|

|

APD: Automated Peritoneal Dialysis; CAPD: Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis |

||

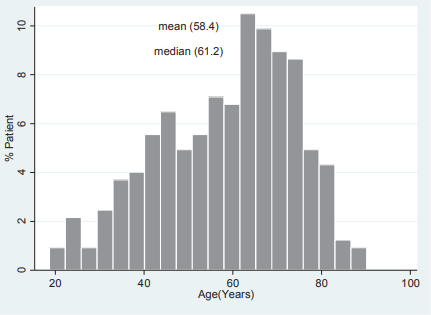

Based on the age distribution of the peritoneal dialysis population (Figure 3),

Figure 3 Summary of age of patients at commencement of peritoneal dialysis

for this study, the population has been sub divided into two Age Group categories (< 60 years (younger) and > 60 years (older)) for comparisons which were both descriptive and analytical and were performed with STATA 14 (Statistics/ Data Analysis), Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA. Intergroup comparisons for continuous variables were analysed with t-tests and Chi-2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of categorical variables. Patient and event characteristics were expressed as mean 1 SD or n (%) for categorical ones. Time to development of discontinuation of peritoneal dialysis (technique failure) and other survival analyses were evaluated using the Cox’s Proportional Hazards regression model. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

OUTCOMES AND RESULTS

Between December 2011 and December 2019, 324 episodes of care in 317 patients were carried out. Currently, 95 individuals remain on peritoneal dialysis, 80 patients (23.4%) have received a kidney transplant, 76 (22.7%) have died and 59 of 324 episodes of care (18.7%) ended with transfer to hemodialysis Figure 2 details the evolution of the episodes of care (and individual patients) considered in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1 along and descriptive and statistical summary of the whole population of the two Age Group sub-cohorts in Table 2.

Whilst most patients were using APD, those in the older age group were more likely to be treated with CAPD compared to the younger age group (p=.022). The proportions of patients with diabetes, either as a primary renal disease diagnosis or as a comorbidity was not surprisingly, higher in the older Age Group (p=.007). Similarly, the likelihood of transplantation was significantly greater in the younger Age group (P<.001) and the proportion of patients dying and or withdrawing from care over the observations period was greater in the older age Group (P<.001).

Of the patient episodes of care that translated to a transfer to hemodialysis, the reasons were broadly similar between the two Age Groups. The numbers of patients were small in nearly all reason categories. Perhaps most notably, peritonitis as a cause of a need to transfer to hemodialysis was similar as were peritoneal membrane failures.

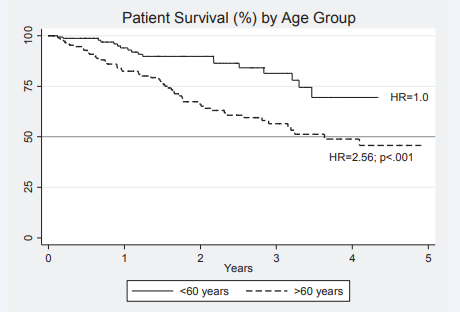

The patient survival and sustainability of the technique are summarised in a series of Kaplan Meier survival plots (Figures 4-6). Patient survival (Figure 4)

Figure 4 Kaplan Meier survival curves for patients on peritoneal dialysis with inferior outcomes for older patients. HR = Hazard Ratio 2.56 (p<.001) compared to younger patients.

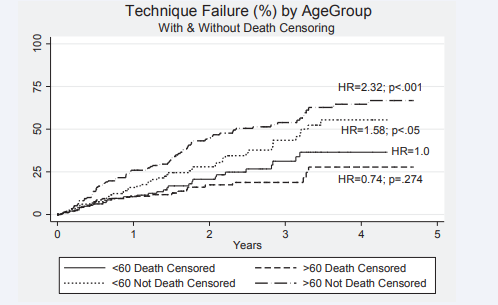

Figure 5 Kaplan Meier survival plots for technique failure on peritoneal dialysis (with and without death censoring) HR= 0.74; p=.274 for death censoring comparing older with younger patients. Outcomes for younger (HR=1.58; p<.05) and older patients. (HR=2.32; p<.001) compared to older patients death censored reaching significance.

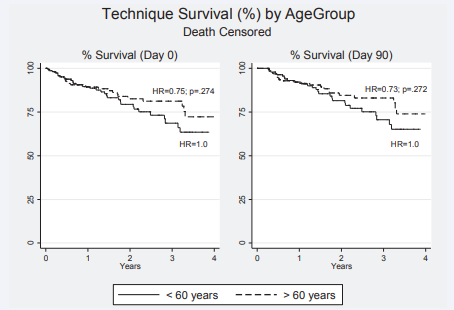

Figure 6 Kaplan Meier survival plots for technique survival on peritoneal dialysis (death censored only) form Day 0 and Day 90 after initiation of therapy- HR= 0.75; p=.274 and HR = 0.73 (p=.072) respectively comparing older with younger patients in both instances.

was inferior for older patients where the hazard ratio HR (hazard ratio (95% CI)) for death was 2.53 (1.56 - 4.30) compared to the younger age group. The 50 percent survival for older patients exceeded 3 years. Censoring the data for death has a major effect on technique failure (survival). Compared to patients < 60 years of age not death censored, the HR for technique failure were 0.74 (0.44 - 1.23) p=.246; 1.58 (1.01-2.48) p=.046 and 2.32 (1.54 -3.50; p75% at 3 years.

DISCUSSION

The reasons for choosing or not choosing a particular dialysis modality (or indeed any modality at all [53]) are very complex [30,54-61] and perhaps more complex in the elderly [62]. One of the influences particularly affecting modality choice in the elderly is the likely accumulated hospitalized time on in-center hemodialysis; nearly 50% in some estimates [63-66]. Despite a burgeoning population of elderly patients requiring dialysis care, relatively few patients are actually offered home-based therapy in the form of peritoneal dialysis [31,67,68] even though older patients can manage the therapy well and can achieve good clinical and patient-relevant outcomes [69] with many opting for more flexibility [70] and less disturbances in their daily lives [71].

The need to develop strategies that promote a psychosocial profile of self-efficacy [72] and self-esteem and therefore the required resilience and confidence [73] may be important for successful home-based dialysis, especially as adverse psychosocial issues are prominent as a cause of discontinuation in the early phases of treatment [74] with peritoneal dialysis. A sense of self-preference is also seminal to longer term survival on the therapy [75]. Early and repeated quality education [72, 76- 85], a characteristic of our Home before Hospital initiative may have the effect of encouraging the uptake of a PD home-based therapy, [86,87] as does the insight of clinicians to enable patients to make a choice [42,83, 88,89]. In addition, multidisciplinary education affects outcomes (mortality and use of central venous catheters, peritonitis, hospitalizations) favorably [87, 90,91] and may also provide cost savings [92]. From our experience over eight years, having a system-wide approach to care with early education and supporting patients in decision making may have been important in improving rates of successful home-based care across all age groups.

Important quality measures on peritoneal dialysis include peritonitis rates. Although the data is not shown State-wide key performance measures of peritonitis rates have indicated our institutional performance [93] consistently < 0.25 episodes/ patient/year. What is shown in the current study is a low rate of conversion from peritoneal dialysis to hemodialysis where ‘peritonitis’ is the nominated reason. Importantly there were no differences in rates between older and younger patients as identified in other studies [69,94]. The quality and effectiveness of the peritoneal home-based therapy was also measured by sustainability of the therapy (technique survival (failure)), where interestingly when censored for death, the technique survival was excellent in older patients although not significantly better than in younger patients.

The number of episodes of care where patients ceased dialysis included 78 of 213 (36.6%) related directly to renal transplantation (Table 2).

Table 2: Comparative Demographics by Age Group.

| Age Group | |||||

| All Episodes of Care (n=324) | < 60 years (n=152) | > 60 years (n=172) | p value (60) | ||

| Age | Mean [SD] | 58.4 +/- 15.5 | 44.8 +/- 10.2 | 70.5 +/- 7.0 | |

| Median [Range] | 61.3 (18.7 - 90.2) | 46.9 (18.7 - 59.9) | 69.2 (60.2 - 90.2) | ||

| Gender | Male | 211 | 96 | 115 | p =.485 |

| Female | 113 | 56 | 57 | ||

| Comorbidity | Diabetes | 134 | 51 | 83 | |

| No Diabetes | 190 | 101 | 89 | p = .007 | |

| Modality | CAPD | 27 | 7 | 20 | p = .022 |

| APD | 297 | 145 | 152 | ||

| Transplanted | 78 | 55 | 23 | P <.001 | |

| Deaths | Deceased | 58 | 15 | 43 | P <.001 |

| Withdrawal (& Death) | 18 | 3 | 15 | ||

| Total | 76 | 18 | 58 | ||

| Transfer to Another Service | 5 | 2 | 3 | p = .789 | |

| Recovered Renal Function | 6 | 5 | 1 | p = .063 | |

| Transfer to Haemodialysis (Reason | Pleural Leak | 11 | 5 | 6 | |

| Unspecified | 11 | 6 | 5 | ||

| Adherence | 3 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Cognition Issues | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Mechanical Issues | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Membrane Failure | 5 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Patient Preference | 6 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Peritonitis (Bacterial) | 9 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Peritonitis (Fungal) | 7 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Sepsis/Diverticulosis | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tunnel/Exit Site Infection | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Total | 59 | 31 | 28 | ||

| p =.193 | |||||

This is a highly desirable outcome and exceeds the national comparative figures tabulated annually in the ANZDATA registry which vary from 23.5% and 27.5% (2013-2017) [95] and averaged over the 13 years to 2012 at 14.5% [96]. Even the rate of proceeding to transplantation in older patients; 23 patients (>60 years of age) of 109 events (22.1%) is quite commend worthy. Transplantation of patients <60 years of age (54 patients of 104 cessation events (49.5%)) is an excellent rate and has important financial implications if transition to transplantation via hemodialysis is no be avoided although in five instances, peritoneal dialysis was supplemented by once/week hemodialysis in a hybrid therapy until transplantation occurred [97]. Also, although the data is inconclusive, and the importance of individualising patient advice has been emphasised [98], some transplant outcomes (short and long-term) after peritoneal dialysis appear to be superior to hemodialysis [36,99-104].

Our study suffers from the limitations of being a single center cohort study. In addition, the model of care and experience might not necessarily be translatable to other jurisdictions. Nonetheless the number of episodes of peritoneal dialysis care is considerable and the outcomes observed are in most areas as good if not superior to other datasets such as recorded in ANZDATA [43,95].

CONCLUSION

At this stage we would be of the view that our model is providing a high level of successful transition to a home-based therapy (centered on peritoneal dialysis) across all age groups. Peritoneal dialysis as in the younger age group, also provides a bridge to transplantation and is a sustainable and successful therapy for older patients if they so choose. Additional qualitative research [105-107] might be needed to confirm the patient’s perception of the experience is consistent with these more traditional outcome measures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript is dedicated to the life and selfless work of our esteemed nursing colleague Jacqueline Ellis who sadly died in 2018.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the substantial contributions of the entire renal team (nursing medical allied health and pharmacists) at Alfred Health for their contribution to the care of the patients in this study. All authors contributed to the collection and organization of the data for this study. RW, SW and PT were involved in data evaluation and analysis.