Changes in the Lactobacillus Species after Treatment of Bacterial Vaginosis with a Nifuratel-Nystatin Combination: A Pilot Study

- 1. Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive medicine, Private Educational

- 2. Institution of supplementary Education, Inozemtsev Academy of Medical Education, RussiaNanodiagnostics LLC, Russia

- 3. Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark

Abstract

Background: We evaluate the composition of vaginal lactobacilli in women with bacterial vaginosis (BV) before and after treatment with a nifuratel- nystatin complex.

Methods: This multicenter prospective observational study included 40 women with abnormal vaginal discharge and a confirmed diagnosis of BV based up on Amsel criteria who received treatment with vaginal capsules containing 500 mg Nifuratel and 200,000 IU nystatin. Quantitative assessment, with typing of Lactobacillus species using real-time PCR and vaginal pH were evaluated before and after treatment. The control group consisted of 25 women without vaginal discharge.

Results: All women had a lactobacillus index (LI) which indicated the proportion of lactobacilli in the total bacterial mass, ranging from 0.01% to 100%, and had a significant diversity in lactobacillus species in both groups. The controls predominantly showed L. crispatus (56.0%), most samples contained two or three species of Lactobacillus and 80% of them had a high LI (>70%). Women with BV demonstrated dominance by L. iners (62.5%) and 32.5% of samples had a low LI (<30%). After the treatment, no women complained of vaginal discharge, and the LI gradually increased. Within 4-6 weeks, detection rates of L. iners, L. crispatus, L. jensenii and L. gasseri reached characteristics comparable to the control group. The vaginal pH was not an indicator of the cure of BV but correlated with the changes of composition of Lactobacilli.

Conclusions: The nifuratel-nystatin complex demonstrated high efficacy in the treatment of BV and has contributed to the restoration of the eubiotic vaginal species of lactobacillus.

Keywords

• Bacterial Vaginosis

• Lactobacillus

• Nifuratel-Nystatin Complex

• Amsel Criteria

• Vaginal pH

• Vaginal Discharge

Citation

Pustotina OA, Demkin VV, Lamont RF (2026) Changes in the Lactobacillus Species after Treatment of Bacterial Vaginosis with a Nifuratel Nystatin Combination: A Pilot Study. JSM Sexual Med 10(1): 1173.

INTRODUCTION

Lactobacillus spp. are the predominant bacteria in the vaginal microbiota of most premenopausal women [1]. Lactobacilli produce lactic acid, provide numerical dominance, prevent pathogen adherence, regulate pH, modulate local immunity and release bacteriocins, which protect the vaginal environment and prevent infectious diseases. Loss of lactic acid-producing lactobacilli causes proliferation of facultative and strict anaerobes and leads to vaginal dysbiosis [2-6]. Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) is the commonest cause of vaginal dysbiosis, vaginal discharge and vaginal infectious morbidity in high income countries. BV has also been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections [7-10]. BV can be diagnosed at the point of care clinically [11], and using the Amsel criteria [12].

In most women with vaginal eubiosis, one of four species of the genus lactobacillus is numerically dominant in the vagina: L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, or L. jensenii [13,14], which corresponds to ravels community state types (CSTs) I, II, III and V [13]. However, not all Lactobacillus species provide vaginal eubiosis. Historically, dominance by L. crispatus, L. jensenii and L. gasseri has been associated with vaginal eubiosis, while an abundance of L. iners with a high diversity of other potentially pathogenic organisms is associated with vaginal dysbiosis and BV [6-17].

BV can be treated with antibiotics [18], and treatment target outcomes include the alleviation of symptoms. The available treatments are effective in the short-term with BV cure rates, of ~80% but recurrence is common in ~50% of women 6-months after treatment [19]. Some antimicrobial drugs may be toxic to lactobacilli and can inhibit their growth, worsening the imbalance in the vaginal microbiota and disrupting restoration of vaginal eubiosis [20-22].

Recently, vaginal capsules containing 500 mg nifuratel and 200,000 IU nystatin with a wide spectrum of activity against micro-organisms responsible for vulvovaginal infections, have been used beneficially to treat women with vaginal discharge, including BV [23-25]. An in vitro study demonstrated high antimicrobial activity of nifuratel against BV-associated pathogens without affecting lactobacilli [26]. The aim of our study was to investigate the prevalence of four dominant species of vaginal lactobacillus (L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, and L. jensenii) among women with BV before and after treatment with the nifuratel-nystatin complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This multicenter prospective observational controlled pilot study was conducted at four public clinics in Moscow between march 15, 2023, and september 28, 2024, in accordance with the World Medical Association Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethic Committee of Private Educational Institution of Supplementary Education “Inozemtsev Academy of Medical Education” (protocol ? 1-2024, 12.07.2024). The study included premenopausal, non-pregnant, non-lactating women. Women with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), abnormal papanicaloa smear test, menopause-related urogenital disorders, severe somatic/gynecological diseases or factors that might prevent study participation were excluded. In addition, the use of systemic or topical antimicrobial drugs, glucocorticoids, or probiotics within the month before enrollment were excluded.

The BV group comprised 40 women aged 18-45 years with symptoms of an abnormal vaginal discharge and an established diagnosis of BV using Amsel criteria. This requires the presence of at least 3 out of 4 criteria: a thin homogenous adherent vaginal discharge, a vaginal pH >4.5, a positive amine test and the presence of clue cells on wet mount microscopy. The control group consisted of 25 women who did not have abnormal vaginal discharge and had a negative Amsel test.

Study protocol

After signing an informed, voluntary consent for study participation, all women were interviewed with respect to their medical history and underwent a standard physical examination including a pelvic examination with speculum for sample collection. Swabs of vaginal fluid were collected for pH evaluation and PCR analysis using polyurethane foam swabs. Women in the BV group were given vaginal capsules containing 500 mg nifuratel and 200,000 IU nystatin (Makmiror® Complex Polichem S.r.l., Italy), to be inserted nightly for 8 days. The control group received no treatment. The study protocol included four in-person visits for the BV group, comprising visit 1 (Screening), visit 2 (days 1-3 post-treatment), visit 3 (days 7-14 post treatment), and visit 4 (weeks 4-6 post-treatment). The control group had only one visit which was the screening visit 1. Swabs of vaginal secretions were taken from the posterior fornix at visits 1, 2, 3, and 4. The pH of the vaginal secretions was measured using Colpo-Test narrow range pH indicator Strips (Biosensor AN LLC, Russia), by visually comparing the colors of the test strip with those of the reference color scale.

DNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the Lactobacillus

DNA extraction and PCR analysis of the vaginal swabs were performed at Nanodiagnostics LLC laboratory (Moscow). Vaginal swabs were collected in “Direct PCR” transport medium for scientific application (Nanodiagnostics LLC), ensuring DNA preservation for at least 30 days at +4°c. DNA extraction from clinical material followed this protocol: an equal volume of “Direct PCR” lysis buffer for scientific application (Nanodiagnostics LLC), was added to the biomaterial volume in the transport medium. One unit of proteinase K was added to the mixture, vortexed, and incubated at 55°c for 15 minutes, then at 95°c for another 15 minutes. After incubation, the mixture was vortexed, centrifuged for 2 minutes at 12,500 rpm, and 5μl aliquots were used in PCR reactions.

Total bacterial mass (TBM) and the total load of lactobacilli (Lactobacillus spp.) were determined by multiplex quantitative real-time PCR using the “Lactoindex V rplK” kit (Nanodiagnostics, Russia). The kit includes primers targeting a conserved region of the 16S rRNA gene for TBM assessment and specific primers and a probe for detection of the rplK gene of vaginal lactobacilli, as previously described [27].

The relative abundance of lactobacilli was expressed as the lactobacillus index (LI), calculated as the ratio of the lactobacilli quantity to the TBM using the formula:

LI (%) = 100 × 2^(k - δCq)

Where:

- δCq = Cq_lacto - Cq_total (provided that δCq > k)

- Cq_lacto is the quantification cycle for lactobacilli (rplK gene)

- Cq_total is the quantification cycle for TBM (16s rRNA gene)

- K = 2.5 is an empirical correction factor accounting for the difference in copy numbers of the rplK and 16s rRNA genes and the differences in their amplification efficiency.

Species-specific identification of lactobacilli (L. crispatus, L. iners, L. jensenii, L. gasseri) was performed by real-time PCR using the “Lactospectrum 4_rplK” kit (Nanodiagnostics, Russia), based on the principles outlined in [28].

PCR was performed in 30 μl volumes using a Biorad CFX 96 amplifier. Amplification program: 95°C for 5 minutes, then 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C, 25 seconds at 60°C, 10 seconds at 72°C.

Assessment of efficacy of BV treatment

Women with BV were considered cured if they had no abnormal vaginal discharge at visits 2 and 3. The recurrence rate of BV was assessed at visit 4 by the presence of an abnormal vaginal discharge and vaginal pH >4.5. Safety parameters were evaluated in all women who received at least one drug dose.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used parametric and non-parametric methods with Microsoft excel 2016 and Statistica 13.3. Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and normal probability plots. Levene’s test evaluated variance homogeneity. Student’s t-test was used for normal distributions, the Wilcoxon test was used for non-normal distributions. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Quantitative indicators between groups were compared using student’s t-test for normal distributions or the Mann Whitney test otherwise. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normal distributions or median and interquartile range Me (Q?; Q?) for other distributions.

RESULTS

A total of 65 patients were enrolled in the study. The 40 women in the BV group had an abnormal vaginal discharge and an established diagnosis of BV and the 25 women in the control group were free of any abnormal vaginal discharge and had a negative Amsel test. The demographic characteristics of women are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, BMI, marital status, parity and smoking habits between the groups.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of patients.

|

Demographic characteristics |

BV group (n=40) |

Control group (n=25) |

|

Age (mean; SD) |

29.7 (8.24) |

30.2 (6.38) |

|

BMI (mean; SD) |

25.7 (2.15) |

24.4 (3.58) |

|

Marital status, n (%) |

|

|

|

Never married |

9 (22.5) |

4 (16.0) |

|

Married |

29 (72.5) |

19 (76.0) |

|

Divorced |

2 (5.0) |

2 (8.0) |

|

Parity, n (%) |

|

|

|

0 |

7 (17.5) |

4 (16.0) |

|

1 |

17 (42.5) |

10 (40.0) |

|

2 |

8 (20.0) |

6 (24.0) |

|

3 |

8 (20.0) |

5 (20.0) |

|

Smoking, n (%) |

9 (22.5) |

7 (25.0) |

P >0.05

Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison of categorical variables and of BV and control groups

BMI – Body mass index BV = Bacterial vaginosis SD= Standard Deviation

TREATMENT EFFICACY

Table 2: Vaginal pH level before and after BV treatment.

|

Vaginal ?? |

BV group |

Control group(n=25) |

|||

|

Visit 1 (n=40) |

Visit 2 (n=21) |

Visit 3 (n=19) |

Visit 4 (n=40) |

||

|

Min; Max |

4,7; 6,5 |

4,5; 6 |

4; 6 |

4; 5 |

4; 5,5 |

|

Mean (SD) |

5,19 (0,42) |

4,98 (0,52) |

4,89 (0,55) |

4,61 (0,28) |

4,41 (0,39) |

|

? 1 |

|

>0,05 |

>0,05 |

0,038 |

0,006 |

|

? 2 |

<0,001 |

0,0241 |

0,046 |

>0,05 |

|

p1 - compared to Visit 1

p2 - compared to control group BV= Bacterial vaginosis

Follow-up examinations at visits 2 and 3 in the BV group showed no evidence of abnormal vaginal discharge. No BV recurrence was detected at 4-6 weeks (visit 4).

Safety Assessment

The treatment was well tolerated by the women in the study group. No adverse events occurred during the treatment or the follow-up period. Specifically, no adverse events were recorded in the BV group treated with Makmiror® Complex vaginal capsules.

Vaginal pH

Normal vaginal pH was considered to be 3.8-4.5. However, in our study, some women in the control group had pH levels of 5-5.5, highlighting the low sensitivity/ specificity of pH alone for vaginal microbiome assessment. Conversely, all women in the BV group had pH >4.5 (Table 2). In the BV group, at visits 2 and 3, despite the absence of vaginal discharge, a normal pH was detected in only 20% of women and only decreased significantly by visit 4, at which stage, the level was comparable with the control group.

Detection rates of Lactobacillus species before and after BV treatment

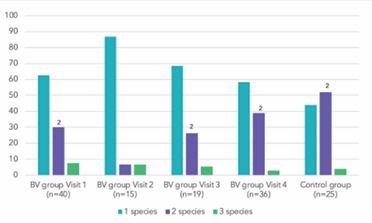

The Lactobacillus characteristics at each visit in the BV and control group, including stratification by LI are shown in Table 3. Of the 40 women in the BV group at baseline, 15 of attended visit 2, 19 at visit 3, and 36 at visit 4. A total of 135 vaginal samples were analyzed (110 in the BV group and 25 in the control group). All four Lactobacillus species were identified in both groups. In 61.5% of these samples one of these species was detected, in 33.3% two and in 5.2% three (Table 4, Figure 1).

Figure 1 Lactobacillus species number in samples before and after BV treatment (%). 2 ?<0,05 compared to Visit 2 BV = Bacterial vaginosis

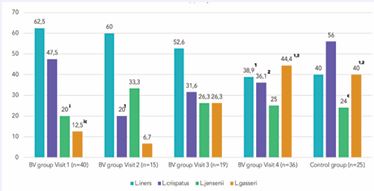

At the baseline visit in the BV group, L. iners dominated (detected in 62.5% of samples), followed by L. crispatus (47.5%), L. jensenii (20%), and L. gasseri (12.5%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Detection rates of Lactobacillus species before and after BV treatment (%) 1p<0,05 compared to Visit 1 2 ?<0,05 compared to Visit 2 ip<0,001 compared to L .iners c?<0,05 compared to L. crispatus BV=Bacterial vaginosis

In the control group, L. crispatus (56.0%) was more common than L. iners (40.0%). The detection rate of L. jensenii was similar to that of the BV group, while the detection rate of L. Gasseri was significantly higher (p<0.05). Most of the samples from women in the BV group (62.5%) contained only one species of Lactobacillus, while the control group samples contained 2 or 3 species (56.0%). Immediately post-BV treatment (visit 2) 86.7% of samples contained only one Lactobacillus species. L. iners still dominated with a 2-fold reduction of L. crispatus (p<0.05) and a slight increase in L. jensenii detection. At subsequent visits 3 and 4, a significant reduction in L. iners detection (p<0.05) occurred contemporaneously with L. crispatus recovery and increased L. gasseri detection (p<0.05). The ratio of L. iners detection compared to other species (L. crispatus, L. jensenii and L. gasseri) began to decrease from 3:1 at visit 2 to 1.87:1 at visit 3 and reached a comparable level to the control group (1.1:1 and 1:1 respectively) at visit 4. Overall, at visit 4, 4-6 weeks post-therapy, the prevalence of Lactobacillus species in samples became almost identical to that of women in the control group.

Table 3: Lactobacillus characteristics in BV and control group, including stratification by LI (n (%)).

|

Lactobacillus species |

BV group |

Control group (n=25) |

|||

|

Visit 1 (n=40) |

Visit 2 (n=15) |

Visit 3 (n=19) |

Visit 4 (n=36) |

||

|

LI <30% |

13 (32.5) |

3 (20.0) |

5 (26.3) |

3 (8.3)1 |

5 (20.0) |

|

1 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

10 (25.0) 9 (22.5) 1 (2.5)i - - |

3 (20.0) 2 (13.3) - 1 (6.7) - |

4 (21.1) 2 (10.5) 2 (10.5) - - |

3 (8.3)1 1 (2.8)1 1 (2.8) - 1 (2.8) |

4 (16.0) - 2 (8.0) - 2 (8.0) |

|

2 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

3 (7.5) 2 (5.0) 2 (5.0) 1 (2.5) 1 (2.5) |

- - - - - |

1 (5.3) 1 (5.3) - 1 (5.3) - |

- - - - - |

1 (4.0) 1 (4.0) - - 1 (4.0) |

|

3 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

|

LI 30 - 70% |

3 (7.5) |

2 (13.3) |

2 (10.5) |

1 (2.8) |

- |

|

1 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

3 (7.5) 2 (5.0) 1 (2.5) - - |

2 (13.3) - 1 (6.7) 1 (6.7) - |

- - - - - |

1 (2.8) 1 (2.8) |

- - - - - |

|

2 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

2 (10.5) 2 (10.5) 1 (5.3) 1 (5.3) - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

|

3 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

|

LI >70% |

24 (60.0) |

10 (66.7) |

12 (63.2) |

32 (88.9)1 |

20 (80.0) |

|

1 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

12 (30.0) 3 (7.5) 7 (17.5) 1 (2.5) 1 (2.5) |

8 (53.3) 6 (40.0)1 1 (6.7)i 1 (6.7)i - |

9 (47.4) 2 (10.5) 3 (15.8) 1 (5.3) 3 (15.8) |

17 (47.2) 4 (11.1) 5 (13.9) - 8 (22.2)1 |

7 (28.0) 2 (8.0)2 4 (16.0) - 1 (4.0)4 |

|

2 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

9 (22.5) 6 (15.0) 7 (17.5) 3 (7.5) 2 (5.0) |

1 (6.7) - 1 (6.7) 1 (6.7) - |

2 (10.5) 2 (10.5) - 1 (5.3) 1 (5.3) |

14 (38.9) 7 (19.4) 7 (19.4) 8 (22.2) 6 (16.7) |

12 (48.0)12 6 (24.0) 7 (28.0) 6 (24.0) 5 (20.0) |

|

3 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

3 (7.5) 3 (7.5) 2 (5.0) 3 (7.5) 1 (2.5) |

1 (6.7) 1 (6.7) - 1 (6.7) 1 (6.7) |

1 (5.3) 1 (5.3) - 1 (5.3) 1 (5.3) |

1 (2.8) 1 (2.8) - 1 (2.8) 1 (2.8) |

1 (4.0) 1 (4.0) 1 (4.0) - 1 (4.0) |

1?<0,05 compared to Visit 1 2?<0,05 compared to Visit 2 4?<0,05 compared to Visit 4 i?<0,05 compared to L. iners LI=Lactobacillus index BV=Bacterial vaginosis.

Table 4: Detection rates of Lactobacillus species in samples with 1, 2 and 3 species before and after BV treatment.

|

Lactobacillus species |

BV group |

Control group n=25 |

||||||||

|

Visit 1 (n=40) |

Visit 2 (n=15) |

Visit 3 (n=19) |

Visit 4 (n=36) |

|||||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

1 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

25 14 9 1 1 |

62,52 35,0 22,5 2,5iic 2,5iic |

13 8 2 3 - |

86,7 53,3 13,3i 20,0 - |

13 4 5 1 3 |

68,4 21,1 26,3 5,3 15,8 |

21 6 6 - 9 |

58,32 16,62 16,6 - 25,01 |

11 2 6 - 3 |

44,02 8,012 24,0 - 12,0 |

|

2 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

12 8 9 4 3 |

30,02 20,0 22,5 10,0 7,5 |

1 - 1 1 - |

6,7 - 6,7 6,7 - |

5 5 1 3 1 |

26,3 26,3 5,31 15,8 5,3 |

14 7 7 8 6 |

38,91 19,4 19,4 22,2 16,6 |

13 7 7 6 6 |

52,02 28,0 28,0 24,0 24,0 |

|

3 species: L. iners L. crispatus L. jensenii L. gasseri |

3 3 2 3 1 |

7,5 7,5 5,0 7,5 2,5 |

1 1 - 1 1 |

6,7 6,7 - 6,7 6,7 |

1 1 - 1 1 |

5,3 5,3 - 5,3 5,3 |

1 1 - 1 1 |

2,8 2,8 - 2,8 2,8 |

1 1 1 - 1 |

4,0 4,0 4,0 - 4,0 |

1p<0,05 compared to Visit 1

2p<0,05 compared to Visit 2

ip<0,05 iip<0,001 compared to L. iners c?<0,05 compared to L. crispatus BV=Bacterial vaginosis

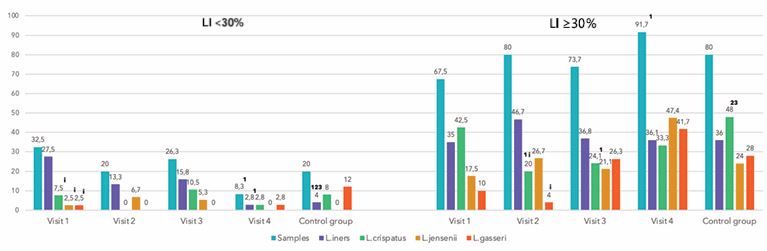

The LI, which indicates the proportion of lactobacilli in the TBM, ranged widely from 0.01% to 100%. While a LI of 100% did not mean absence of other bacteria, it indicated that their quantity compared to lactobacilli did not exceed 1%. Most samples (72.6%) revealed a high LI (>70%), 5.9%, a moderately reduced LI (30-70%) and 21.5% a low LI (<30%). Samples with high and moderately reduced LI contained predominantly L. iners and L. crispatus (47.2 and 46.2% respectively) (Table 5).

Table 5: Detection rates of Lactobacillus species in samples with LI below and above 30%.

|

Lactobacillus species |

LI <30% (n=29) |

LI ≥30% (n=106) |

? |

|

L. iners, n (%) L. crispatus, n (%) L. jensenii, n (%) L. gasseri, n (%) |

18 (62.1) 8 (27.6)i 3 (10.4)ii 5 (17.2)ii |

50 (47.2) 49 (46.2) 30 (28.3)ic 32 (30.2)ic |

0.148 0.055 0.014 0.120 |

ip<0,05 compared to L. iners iip<0,001 compared to L. iners cp<0,05 compared to L. crispatus LI=Lactobacillus Index

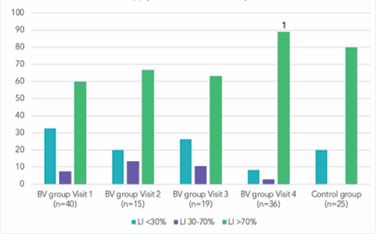

L. jensenii and L. gasseri were detected less commonly (28.3 and 30.2% respectively) (p<0.05). In samples with low LI (<30%), detection rates of L. iners significantly exceed those of other species (p<0.05) (Figure 3). A high LI was detected in 80% of samples from the control group and 60% in the pre-treatment BV group (Figure 4). Both groups also had samples with a LI of 70% (p<0.05).

Figure 3 Lactobacillus characteristics before and after BV treatment in LI < and ≥ 30% (%)

1?<0,05 compared to Visit 1

2?<0,05 compared to Visit 2

3?<0,05 compared to Visit 3

i?<0,05 compared to L.

iners BV=Bacterial vaginosis

LI=Lactobacillus index.

Figure 4 Lactobacillus Index (LI) before and after BV treatment (%)

1 ?<0,05 compared to Visit 1

LI=Lactobacillus index

BV=Bacterial vaginosis.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, our pilot study is the first to demonstrated changes in the prevalence of four dominant species of vaginal lactobacillus (L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. iners, and L. jensenii) among women receiving treatment for BV using nifuratel-nystatin vaginal capsules. In addition, the cure and recurrence rates of BV, and pH correlation with lactobacillus were evaluated over 4-6 weeks post-therapy. BV cure (absence of vaginal discharge) and no disease recurrence were observed in all women. The treatments were well tolerated by women and no adverse events occurred during the treatment or follow up period. This finding corroborates other studies on the efficacy and safety of the nystatin-nifuratel combination in the treatment of BV [23-25], and provides us with a great opportunity to assess changes in the prevalence of lactobacillus species in the vagina after treatment among all women enrolled in the study.

In women with BV the vaginal pH always exceeded 4.5, and in 12.0% of women in the control group it was also increased. The absence of vaginal discharge after BV treatment was not always accompanied by a return of the vaginal pH to <4.5. pH reduction to levels comparable to those of the control group occurred only at 4-6 weeks post treatment and correlated with changes in li.

Quantitative assessment and typing of Lactobacillus spp using real-time PCR of 135 vaginal samples (25 from controls, 110 from the BV group) found lactobacilli in quantities ranging from 0.01% to 100% of the TBM. During the identification process, at least one of four Lactobacillus species (L. iners, L. crispatus, L. jensenii, or L. gasseri) were identified in each sample. The control group predominantly showed L. crispatus (56.0%), while other species had a prevalence of 24.0-40.0%, and most samples (56.0%) contained two or three Lactobacillus species. Women with BV showed Lactobacillus species with L. iners dominant (62.5%) and less frequently L. crispatus (47.5%). L. jensenii and L. gasseri detection was significantly lower than in controls (p<0.05).

These results confirm the special role of L. crispatus and L. iners as key species of Lactobacillus in the vaginal microbiome [3-15]. However, while the trends were clear, the difference between individuals was high. The findings also failed to reveal a strict correlation between the relative abundance of lactobacilli in the TBM, as well as vaginal pH, in women with a clinical manifestation of BV such as discharge. Analysis of the relative abundance of lactobacilli in the TBM, revealed a high LI (>70%) in most samples in both groups (60.0% pre-BV treatment, 80.0% controls). Both groups also contained samples with extremely low LI (<30%), including near-zero levels. This indicates that a lack of lactobacilli does not always lead to BV, and that while vaginal dysbiosis is usually symptomatic, this is not always the case [2-29]. Conversely, this could support the view, that a normal vaginal microbiome is characterized by the presence of a beneficial microbiota producing lactic acid, predominantly but not exclusively from the genus Lactobacillus [11-15]. Nevertheless, the study of post-BV treatment showed a gradual increase in the lactobacilli proportion of TBM from 60 to 88.9% (p<0.05). Consequently, at post BV treatment follow up, the level of LI exceeded the control group. This being the case, it confirms that lactobacilli are key members of the vaginal microbiome, providing vaginal eubiosis for the host.

Significant post-BV treatment changes were noted in the detection rates of individual spp of Lactobacillus. In the first days after nifuratel-nistatin combination therapy, lactobacillus species diversity significantly reduced, and 9 out of 10 vaginal samples contained only one species, where L. iners prevalence was 61.5%. However, by visit 3, L. iners detection already decreased while L. crispatus and L. gasseri recovered. At visit 4, detection rates of L. iners, L. jensenii and L. gasseri were like those of the control group, and the prevalence of L. crispatus continued to increase. In contrast to L. crispatus, which was less abundant in BV, the presence or absence of L. iners did not differentiate between BV and the control groups. This supports the suggestion that L. iners may be better adapted to the conditions associated with BV [15]. In addition, the increase in the relative abundance of L. Iners immediately after BV-treatment may be the result of its having a better capacity to tolerate antimicrobial drugs, and adapt to environmental fluctuation such as changes in pH, sexual intercourse, endocrine changes, mucus concentration, menstrual bleeding, and infection [17]. It is likely that the increase in the proportion of L. iners in TBM was due to a reduction in BV-associated bacteria post antibiotics rather than by the growth of an abundance of lactobacilli. We also noted an increase in the frequency of L. jensenii and L. gasseri detection in post-BV treatment samples. These species are more common in cases of moderate or asymptomatic dysbiosis [1-30], which suggests that they play a transitory role and possibly characterize a transitional state between dysbiosis and eubiosis.

In summary, our results demonstrated significant diversity in the Lactobacillus spp prevalence in both the control and BV group of women. We found no direct correlation between the relative abundance of total and/ or individual species of Lactobacillus in samples from women symptomatic or asymptomatic of abnormal vaginal discharge, despite observable trends with respect to L. crispatus and L. iners, Lactobacillus spp diversity and the proportion of a high or low LI. Nevertheless, we have observed certain changes in the lactobacillus spp community after BV-treatment with vaginal capsules, containing nifuratel and nystatin: i) the relative abundance of lactobacillus spp in TBM increased immediately after treatment and continued for 4-6 weeks post-treatment; ii) L. iners and L. jensenii seem to be tolerant of topical application of nifuratel-nystatin complex, whereas the growth of L. crispatus and L. gasseri was temporarily suppressed during BV treatment; iii) 1-2 weeks post treatment, the ratio of L. iners to the prevalence of other Lactobacillus species (L. crispatus, L. jensenii and L. gasseri) began to decrease, and after 4-6 weeks, the lactobacillus spp prevalence reached characteristics comparable to the control group and iv) the vaginal pH was not an indicator of BV cure but correlated with changes in the lactobacillus species abundance.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

The limitations of our study are that BV was diagnosed using Amsel criteria, and the control group was chosen only by the absence of abnormal vaginal discharge and negative Amsel tests. Nugent scoring of vaginal gram stains could have improved the assessment of the vaginal microflora, which might have detected a greater correlation with changes in the lactobacillus species abundance. The vaginal samples were not investigated by PCR analysis for the non lactobacillus community, which led to certain limitations in the assessment of the vaginal microbiome before and after BV treatment. In addition, the follow-up period was limited to 4-6 weeks, which prevented conclusions about the long-term effects of treatment on vaginal lactobacillus species.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability of vaginal capsules containing nifuratel-nystatin combination for the treatment of BV. The vaginal pH was not a reliable indicator of BV cure but correlated with changes in the abundance of Lactobacillus species. In the first days after nifuratel-nystatin therapy, the species diversity of Lactobacillus temporarily decreased, and the pH remained at the pre-treatment level, but the relative abundance of Lactobacilli in TBM began to increase. After 4-6 weeks, quantitative and qualitative indicators of the prevalence of lactobacillus species, as well as vaginal pH, reached characteristics comparable to the control group. However, a significant variety in Lactobacillus spp abundance observed in women with or without of abnormal vaginal discharge indicates that a Lactobacillus abundant vaginal microbiota does not always protect against the development of BV. Laboratory dysbiosis, manifested by a lack of lactobacilli, also does not strongly correlate with clinical BV and may be asymptomatic. In the case of BV, accompanied by a decrease in the proportion of Lactobacilli, this condition may persist for several days after the treatment, but over time (4-6 weeks), the dominance of Lactobacilli can be restored to eubiosis on its own, without additional therapeutic treatment, including probiotics.

Based on our findings, the next step in the investigation of the vaginal microbiome is to examine the lactobacillus and non-lactobacillus community following treatment with BV using different drugs, and to contrast the restoration to eubiosis with and without the use of probiotics. This novel study with more in-depth methodology will provide us with a deeper insight into the impact of different treatment modalities on the vaginal microbiota and the prevention of recurrent BV.

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethic Committee of Private Educational Institution of supplementary education “Inozemtsev Academy of Medical Education” (protocol ? 1-2024, 12.07.2024). Written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Consent for the publication

All the patients had given a written informed voluntary consent to participate in the study and publish their data.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy reasons but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study was supported by the “expertology” scientific-educational project. The authors report no other funding for study development, conduct, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation, review, or approval.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: o.a.p., v.v.d.; original draft preparation: o.a.p., v.v.d., r.f.l.; all authors were involved in the review, revision and editing of the manuscript and have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Mancabelli L, Tarracchini C, Milani C, Lugli GA, Fontana F, Turroni F, et al. Vaginotypes of the human vaginal microbiome. Environ Microbiol. 2021; 23: 1780-1792.

- Verstraelen H, Vieira-Baptista P, De Seta F, Ventolini G, Lonnee- Hoffmann R, Lev-Sagie A. The Vaginal Microbiome: I. Research Development, Lexicon, Defining “Normal” and the Dynamics Throughout Women’s Lives. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2022; 26: 73-78.

- Kwon MS, Lee HK. Host and Microbiome Interplay Shapes the VaginalMicroenvironment. Front Immunol. 2022; 13: 919728.

- Chen X, Lu Y, Chen T, Li R. The female vaginal microbiome in Health and Bacterial Vaginosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021; 11: 631972.

- Kovachev S. Defence factors of vaginal lactobacilli. Crit Rev Microbiol.2018; 44: 31-39.

- Lamont RF, Sobel JD, Akins RA, Hassan SS, Chaiworapongsa T, Kusanovic JP, et al. The vaginal microbiome: new information about genital tract flora using molecular based techniques. BJOG. 2011; 118: 533-549.

- Kahwati LC, Clark R, Berkman N, Urrutia R, Patel SV, Zeng J, et al. Screening for Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnant Adolescents and Women to Prevent Preterm Delivery: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020; 323: 1293-1309.

- McKinnon LR, Achilles SL, Bradshaw CS, Burgener A, Crucitti T,

Fredricks DN, et al. The Evolving Facets of Bacterial Vaginosis: Implications for HIV Transmission. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2019; 35: 219-228.

- Hillier SL, Marrazzo J, Holmes KK. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Mardh PA, et al., eds. Sexually transmitted diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2008: 737-768.

- Khedkar R, Pajai S. Bacterial Vaginosis: A Comprehensive Narrative on the Etiology, Clinical Features, and Management Approach. Cureus. 2022; 14: e31314.

- Bornstein J, Bradshaw C, Plummer E, Aidé S, Borella F, Edwards L, et al. In: Bacterial vaginosis: Edited by Vieira-Baptista P, Stockdale CK, Sobel J. International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of vaginitis. Lisbon: Admedic. 2023: 61-95.

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, HolmesKK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983; 74: 14-22.

- Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108: 4680-4687.

- Demkin VV, Koshechkin SI. Lactoflora species diversity in the vaginal microbiome of Russian women. Molecular Genetics, Microbiology and Virology. 2024; 42: 25-31.

- Lamont RF, van den Munckhof EH, Luef BM, Vinter CA, Jørgensen JS. Recent advances in cultivation-independent molecular-based techniques for the characterization of vaginal eubiosis and dysbiosis. Fac Rev. 2020; 9: 21.

- Han Y, Liu Z, Chen T. Role of Vaginal Microbiota Dysbiosis in Gynecological Diseases and the Potential Interventions. Front Microbiol. 2021; 12: 643422.

- Petrova MI, Reid G, Vaneechoutte M, Lebeer S. Lactobacillus iners:Friend or Foe? Trends Microbiol. 2017; 25: 182-191.

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021; 70: 1-187.

- Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009; 22:82-86.

- Neut C, Verrie?re F, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Topical Treatment of Infectious Vaginitis: Effects of Antibiotic, Antifungal and Antiseptic Drugs on the Growth of Normal Vaginal Lactobacillus Strains. Open J Obstetr Gynecol. 2015; 5: 173-180.

- Aroutcheva A, Simoes JA, Shott S, Faro S. The inhibitory effect of clindamycin on Lactobacillus in vitro. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 9: 239-244.

- Simoes JA, Aroutcheva AA, Shott S, Faro S. Effect of metronidazole on the growth of vaginal lactobacilli in vitro. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 9: 41-45.

- De La Hoz FJE. Efficacy and safety of the combination nifuratel- nystatin and clindamycin-clotrimazole, in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Reprod Med Sex Health. 2021; 3: 01-10.

- De La Hoz FJE. Efficacy And Safety of Nifuratel-Nystatin in The Treatment of Mixed Vaginitis, in Pregnant Women From Quindío, 2013-2017. Randomized Clinical Trial. Pregn Womens Health Care Int J. 2022; 2: 1-7.

- Apolikhina A, Guschin AE, Efendieva ZN, Tyulenev YuA. Opportunities for antimicrobial therapy of diseases accompanied by pathological discharge from the genital tract: results of the multicenterobservational Prospectus program. Obstetr Gynecol. 2021; 12: 167-176

- Togni G, Battini V, Bulgheroni A, Mailland F, Caserini M, MendlingW. In vitro activity of nifuratel on vaginal bacteria: could it be a good candidate for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011; 55: 2490-2492.

- Demkin VV, Koshechkin SI, Slesarev A. A novel real-time PCR assay for highly specific detection and quantification of vaginal lactobacilli. Mol Cell Probes. 2017; 32: 33-39.

- Demkin VV, Koshechkin SI. Characterization of vaginal Lactobacillus species by rplK -based multiplex qPCR in Russian women. Anaerobe. 2017; 47: 1-7.

- Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, MacPherson CA, Carey JC, Heine RP, Wapner RJ, et al. National Institute for Child Health and Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network. Time course of the regression of asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy with and without treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004; 190: 363-370.

- Zornikov DL, Tumbinskaya LV, Voroshilina ES. The relationship of individual species of lactobacilli with the total proportion of lactoflora in the vaginal microbiocenosis and groups of opportunistic microorganisms associated with vaginal dysbiosis. Bulletin of the Ural Medical Academic Science. 2015; 4: 99-105.