Child Sexual Abuse in Nigeria: A Systematic Review

- 1. Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Sheffield, England

- 2. Department of Nursing and Gender-Based Violence, University of Sheffield, England

- 3. Department of Child, Family Health and Wellbeing, University of Sheffield, England

Abstract

Child sexual abuse is a major social and public health issue which creates short- and long lasting impacts on victims, families, and society. While global researchers have considered the topic of CSA since the 19th century, the Nigerian context has been largely ignored. Yet, without sufficient evidence and understanding, making changes to practices and policies becomes almost impossible.

This article presents the findings of a systematic review of the 31 available empirical articles related to CSA in Nigeria. Using key search terms along Boolean operators and truncation, the PubMed, Psyc INFO, CINAHL, ASSIA, PILOTS, and African Journals Online (AJOL) and Google Scholar were searched. A total of 31 empirical studies including 20 quantitative, nine qualitative and two mixed methods studies were included.

This section presents the discourse on child sexual abuse and delves into various aspects such as its prevalence, manifestation patterns, root causes, and consequential impact on victims and societal domains. Additionally, the gaps in the existing literature are identified and explored to identify areas for improvement in victim services, societal awareness, and healthcare practices. Children’s vulnerability to sexual abuse was heightened by socio-cultural norms which also acted as barriers to the child disclosing the abuse. Evidence suggests that survivors of child sexual abuse often receive inadequate care, indicating a pressing need for improvements in this area. Implications for research and conclusion from this review were discussed.

Keywords

• Child sexual abuse

• Nigeria

• Health Care Practitioners

• Children

• Victims

• Prevalence

• Parent perception on CSA and Barriers to disclosure

CITATION

Ifayomi M, Ali P, Ellis K (2023) Child Sexual Abuse in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. JSM Sexual Med 7(4): 1119.

INTRODUCTION

Child sexual abuse (CSA) occurs when a child is involved in sexual activity without understanding or being able to give informed consent, or when the activity violates laws or social norms [1,2]. CSA can be physical or non-physical, penetrative, non-penetrative, and has serious long-term effects on victims. According to WHO, one in four children globally experiences some form of sexual abuse. The prevalence of CSA in Nigeria is largely unknown and estimates range from 2.1 to 77.7% [3,4]. More than 31.4% of girls’ first sexual experience in Nigeria was reported to be rape or forced sex (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Funds, 2015). The actual magnitude of CSA remains unknown, with disparities in published statistics across the world [4,5] as it is highly underreported and underestimated.

The causes of CSA are multifaceted, comprising individual, contextual, and environmental factors that increase a child’s vulnerability [6]. Young children, for example, can be particularly vulnerable to CSA due to their higher level of dependency,

inability to protect themselves, and difficulty articulating their experiences or seeking help [7,8]. In addition, they are sometimes unable to see sexual exploitation when disguised as love, protection or friendship [6,9]. In addition, children with a learning or physical disability, children being looked after away from home and children with interrupted care histories [10,11] are more at risk of experiencing CSA.

CSA entails short-term and lifelong sequel for the individual, family and society, especially if left unrecognised or untreated [12,13]. CSA has become a serious challenge in all societies, increasing victims’ risk of developing a wide range of physical and mental problems. The consequences are numerous and pervasive, and they may affect the physical, psychological, emotional, social, moral, educational and economic wellbeing of victims [12,14]. Victims of CSA can experience both physical (genital trauma, unplanned pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases), psychological (depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, self-blame, distrust, and anger), emotional (fear and

anxiety), and behavioural difficulties (mistrust of others and missing from home) [15,16,17] Such experiences can also leave victims traumatised by unsavoury memories, which can truncate psychosocial development and impede educational careers [13,14].

The true burden of CSA in Nigeria remains unknown and difficult to determine as most available data are collected through social media and cases presented at hospitals. The research team intends to delve deeper into the perspectives and methods employed by healthcare professionals in their line of work. The culture of silence around CSA have masked the extent of CSA. In addition, limited research has been conducted to aggregate the existing evidence around CSA in Nigeria. The few existing peer- reviewed articles from Nigeria are from clinical cases, and do not account for the many cases that never reach a clinic. This leaves out evidence that may be present among children in and out of school, and adolescents from both secondary and tertiary institutions. Therefore, it is important to systematically appraise the few empirical studies available in Nigeria to aggregate the available evidence and understand the nature and extent of CSA in Nigeria. More specifically, the research team was interested in exploring the context in which the HCPs supporting sexually abused children in Nigeria operate.

The aim of this review is to aggregate and critically appraise the quality of the available evidence to identify what was known about CSA in Nigeria and highlight gaps in the existing literature, and develop a theoretical framework to underpin and design subsequent studies. Our specific aim was to systematically review the existing body of knowledge on CSA in Nigeria; the prevalence and pattern of CSA, its causes, determinants, impacts, and Healthcare Professional understanding and working practices.

METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

A systematic review approach was used to conduct exhaustive searches to identify and review all available peer reviewed literature on CSA in Nigeria. Studies were considered eligible for review if they were (i) empirical in nature, (ii) explored any topics on CSA in Nigeria, and (iii) published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals and (iv) in English language (which is the official language in Nigeria) and (v) published between 1st January 1999, and May 2022. Literature from this period was included as the period signifies significant milestone such as awareness and research on CSA and professional attention to victims of CSA in Nigeria. Table 1 show inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 1: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

|

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Focused on CSA prevalence, pattern and impacts |

Studies that did not focus on CSA |

|

Focused on society perception of CSA |

Studies conducted before 1st Jan 1999 |

|

Focused on healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes, or awareness of CSA |

Literature reviews including either narratives or systematic or meta- analysis reviews and commentaries |

|

Focused on the present CSA intervention in Nigeria, issues and challenges facing HCPs |

Ph.D. thesis |

|

Only studies published in the English Language |

Not published in English |

|

Between the years 1st January 1999 to May 2022 |

Studies conducted before 1st January 1999 |

|

Published in peer reviewed journal |

|

Note. A description of inclusion and exclusion criteria

Data Sources

For a comprehensive literature review, the following six databases were systematically searched: PubMed, PSYCINFO, CINAHL, ASSIA, PILOTS and African Journals Online (AJOL), as well as Google Scholar was also used in order not to miss out any studies not indexed. Also, the reference list of all articles included were keenly searched to identify other relevant empirical

studies. Boolean operators (AND and OR) and truncation (*) was used, alongside some of these keywords: ‘Child sexual abuse and pattern’, ‘Prevalence and child sexual abuse’ ‘Child sexual abuse and causes’ ‘Child abuse AND Nigeria’, ‘healthcare professionals AND child sexual abuse’, ‘Nigeria AND girls AND abuse’, ‘Nigeria AND sexual child abuse OR sexual exploitation’, ‘Doctors OR Nurse AND child sexual abuse OR child molestation’, ‘Nigeria AND issues and challenges AND healthcare providers’, ‘Barriers AND detecting Child abuse in Nigeria’.

Study Selection, Quality Appraisal, and Data Extraction

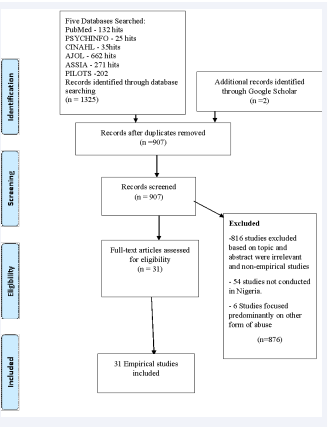

Following a comprehensive search, a total of 1325 studies were identified. Following exclusion of 418 duplicates, 876 irrelevant studies (did not meet the inclusion criteria, were not empirical, were not conducted in Nigeria, or do not focus on CSA) were excluded. Review of the titles and abstracts resulted in the selection of 31 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The full text was retrieved for all 31 articles and an independent reviewer read these articles and all peer checked to determine suitability for inclusion. Only 31 empirical studies that met the inclusion criteria were included. Figure 1 shows

Figure 1: PRISMA Flowchart of Study Selection. Note. A process of selecting and reasons for excluding articles for this review

the PRISMA flowchart from identification of studies to the inclusion process.

A data extraction form was used to excerpt relevant information, the author names, year of study, aims of the study, design, settings, methodology, sample size, the study’s results and limitations of the studies. Similar concepts were clustered together to present findings. Each study that met the inclusion criteria was quality assessed using the critical appraisal skill programme (CASP) checklists, including the qualitative checklist (for qualitative studies), cohort study checklist (for quantitative studies and case-control study checklist). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) Version 2011 was employed for quality evaluation of mixed methods studies. Study results were also analysed to summarise prevalence of various forms of CSA, patterns of CSA, causes and determinants/predictors, consequence and impact on victims, family and society, society’s awareness and attitude towards CSA and victims and HCPs’ perceptions and practices and available services and identifying issues and challenges. Similar concepts were clustered togetherto present findings.

RESULTS

Description of studies setting, population, design and methodology

Table 2

Table 2: Summary of the Included Study

|

ID |

Authors & years |

Design & Method of data collection |

Setting and Geopolitical zone |

Participants |

Results & Conclusion |

Limitation |

|

1. |

Obisesan, Adeyemo & Onifade (1999) |

Quantitative Cross-sectional study Questionnaire Multi-stage sampling |

7 Local Government Areas (LGAs) Oyo State South West Nigeria |

4000 (2000 men and 2000 women) Occupation: Not mentioned Age: Adult |

Prevalence: 2.1%, 5% had sex between ages 6 and 10. Contributing factors: living in boarding houses. Boys are more sexually abused than girls (2.4%) Conclusion: There is a great need for more studies on child sexual abuse in Nigeria |

Memory recall and response bias Limited reliability and validity |

|

2. |

Ogunyemi (2000) |

Mixed method Interview, Focused group Questionnaire Random sampling techniques |

Ijebu Ode Community Ogun state, South West Nigeria |

958 participants Occupation: Market leaders, Religion leaders, School Principal, Occupational leaders Aged: Adult |

Prevalence – Girls-38%; Boys-28% Leading cause of sexual initiation: Rape/date rape, and child prostitution were frown at but gender-role stereotyping still exists. Reason for first sexual experience among respondents: date rape, boyfriend/girlfriend relationships, and pornography. Conclusion: Gender stereotypes and social stigma affect CSA disclosure. Secrecy around sex creates barriers to disclosure for girls. Empowering girls to share their experiences is important. |

Response and recall bias. |

|

3. |

Ajuwon, et al. (2001) |

Quantitative

Questionnaire Random Sampling technique |

Ibadan South-West Nigeria |

1,025 Occupation: Adolescent students and Apprentices Age: 15 to 19 years |

Prevalence- 68% to 70% Students: 68% of female and 42% of male Apprentices: 70% of females and 40% had experienced at least one coercive behavior. Over 50% of girls have collected money or gifts for sex. Perpetrator: Boyfriends and adults male. Four common types of sexual coercion experienced: unwanted hand holding/unwanted sexual touch, verbal threat, unwanted kiss and breast touch. |

Limited reliability |

|

4. |

Audu, Geidam, & Jarma (2008) |

Quantitative Questionnaire Simple random sampling |

Maiduguri Nigeria NorthEast |

316 girls Occupation: Sales girls Age: 8 to 19 |

Prevalence: 77.7% Perpetrators: Customers. Girls under 12 years not in formal education, working more than 8 hours/day or having two jobs are at higher risk of sexual assault. |

Limited reliability |

|

5. |

Bankole, Denloye, & Adeyemi, (2008) |

Quantitative Questionnaire Random Sampling |

University College Hospital, Ibadan Southwest. |

175 participants Occupation: Dentists Age: Adult |

39.4% of the dentists suspected child abuse in one or more of their young patients however, only 6.9% had actually reported. The possible effects on the child, uncertainty about the diagnosis and fear of litigation |

Small SampleLimited generalisation |

|

6. |

Ikechebelu et al. (2008) |

Quantitative Descriptive survey Questionnaire Convenient Sample |

Two urban settlements Anambra State South East |

186 girls Occupation: Street hawkers Age: 7 to 16 |

Prevalence: 7 in 10 female (69.9%) 17.2% had actual penetration. 75% did not disclose, 25% disclosed to family members and friends and only one case was reported to police. |

Small sample Limited generalisation |

|

7 |

Oteh, Ogbuke, & Iheriohanma(2009) |

Qualitative Interview Purposive sampling |

Ezza community Ebonyi state. South East |

60 participants Fifty children (50) and ten (10) parents |

Majority of the parent claimed they subjected their children to abuse because of economic burden. Result: Exploitation prevents child education (35%), reduces their future capacity (40%), and reduces their economic contribution (20%). |

Limited generalisation |

|

8. |

Aderinto, (2010) |

Qualitative Focus Group Discussions Interviews Convenient sampling |

Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria |

Adolescents girls Age: 18 to 20 years Communities and religious leaders Age: Adults |

Causes: Child labour is a common cause of CSA. Disclosure: Victims often confide in friends and family, rarely reporting abuse to the police. In some cases, perpetrators marry or disappear. Suggestion: Government should outlaw early marriages, children dropping out of schools, street trading and child labour. |

Limited generality |

|

9. |

Abdulkadir et al. (2011) |

Quantitative Retrospective study of cases |

General Out-patient Department, General hospital Minna. North Central Nigeria. |

32 cases of penile penetration |

Most cases reported are children under 17, with 75% aged 6 to 15. Only two boys out of 32 cases were reported. Form of abuse reported: vaginal penile and anal penetration. Only 4 cases presented with 24 hours, 21 after 72 hours. Conclusion: Healthcare providers need to build their capacity to manage child sexual abuse and its long-term consequences |

Non-in-depth response |

|

10. |

Ige & Fawole, (2011) |

Quantitative Questionnaire |

Idikan Ibadan Southwest Nigeria |

387 parents Occupation: Petty Traders And Artisans Age: Adult |

All have good knowledge of CSA. >90% discuss with children stranger danger. 47% felt their children could not be abused, and over a quarter (27.1%) often left their children unsupervised. Common approaches to identifying CSA: genital or anal injury checks, and signs of abnormal sexual interest in their children. |

Non-in-depth response |

|

11 |

Adeleke et al (2012) |

Quantitative study Retrospective study descriptive statistics and Chi squire test. |

State hospital, Asubiaro, Osogbo, Nigeria South West |

Hospital records of victims |

Most of the victims were under 18 years old and single. Around 81% of those under 18 were abused during the day. A majority (79.6%) knew their assailant. About 40% of the victims presented within 24 hours of sexual abuse, but none had postexposure prophylaxis. Conclusion: Sexual assault among women is an important health problem in this environment. There is need for hospital-based management protocol |

Non-in-depth response |

|

12. |

Ige & Fawole, (2012) |

Quantitative Retrospective cross sectional study. (June 2008-May 2009) |

University College Hospital Ibadan Southwest Nigeria |

Age: 3 to 17 years |

Cases were reported between one hour and 30 days. About three-quarters of patients in this study had investigations for STI. Only 34% received antibiotics, with few getting counseling or contraceptives. Conclusion: CSA victims' healthcare needs in Nigeria are underserved. |

Non-in-depth response |

|

13. |

Olatunya et al. (2013) |

Quantitative Retrospective, descriptive study |

Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital South West |

28 cases of CSA Occupation: Not mentioned Age: 4 to 17 years |

Perpetrator: Adult male. Management: 60.7% were screened for hepatitis B and C and HIV. None was given prophylaxis against viral hepatitis B and C. The police were involved in 60.7% of cases, but there was no prosecution. |

Clinical and small sample. |

|

14. |

Aborisade & Vaughan (2014) |

Qualitative study Interview Convenient Sampling |

Tai Solarin University of Education South West |

27 Participants 23 rape victims and 4 key informants |

Prevalence: Over 50% experienced stranger and gang rape. Only 3 out of 23 received family support. Over 60% of the 23 victims faced secondary victimisation from their close ones. Only 2 victims fully adjusted to the situation, while none of them sought legal action. Only one victim received comprehensive medical and psychological care Consequence: psychological problem (suicide attempts, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and emotional (fear and anxiety) and behavioral dif?culties. |

Response bias |

|

15 |

Akinlusi et al. (2014) |

Retrospective study

Epi-info 3.5 statistical software |

Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Ikeja, between January 2008 and December 2012. South West |

304 case notes reviewed |

Out of 304 sexual assault cases, 287 had sufficient information. The majority of victims were under 19, knew attackers, and assault happened in neighbors' homes. Over 60% presented after 24 hours, and threats/violence were common. Adolescents need protection skills, and survivors delay care. Conclusion: Early interventions and comprehensive care of survivors with standardised protocols are recommended. |

Non-in depth response |

|

16 |

Badejoko et al. (2014) |

Quantitative study Retrospective analysis- 5years (2007-2011) |

Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals, Ile-Ife South West |

Hospital records of 76 SA survivors managed |

Perpetrators were known by victims, attacks often happened in the attacker's home, and weapons were used in 29.6% of the cases. About 28.2% of survivors sustained injuries. Only 12.7% of victims came to follow-up visits. Conclusion: Personnel training, protocol development, provision of rape kits, free treatment, and public enlightenment on preventive strategies are recommended. |

Non-in depth response |

|

17. |

Chinawa et al. (2014) |

Quantitative, Questionnaire Systemic Sampling |

Private Secondary school setting Enugu Metropolis South East Nigeria |

372 Teenagers, 192 females and 180 males. |

Prevalence -10.2% 81.6% of which were females. 42.1% experienced unwanted sexual intercourse. 44.8 % were emotional, while 16.8 were physically abused. Conclusion To combat medical malpractice, we need to raise awareness and implement zero-tolerance laws. |

Limited reliability and validity |

|

18 |

?Ashimi, Amole, and Ugwa (2015) |

Prospective longitudinal study -2 years |

Gynecological Emergency Unit of a Tertiary Health Facility Northwest |

24 case notes of children under 16 |

Prevalence: 91.7% of case notes belong to children under 16. 45.8% (11/24) had no formal education. while 33.3% (8/24) hawked homemade drinks and snacks. Conclusion: The assailants were known in 83.3% (20/24) of the cases. The perpetrators are known; they were neighbours, customers and family members. |

Non-in depth response |

|

19. |

Elias et al (2015) |

Quantitative study Questionnaires Simple random sampling |

Three secondary school, Enugu and Ebonyi state

South east, Nigeria. |

506 Participants

Age: 10 to 24 years |

Prevalence: Overall prevalence and one time prevalent is 40% and 11.5% respectively and almost half had lost count of pattern. Females were more vulnerable, four times. It is also noted that 1 in 4 girls (25%) are sexually abused by the age of 18. Commonest form of abuse reported: Pornographic pictures, films, videotapes or magazine. Perpetrators exposing genitals and masturbating, and coerced into full sexual intercourse ; vaginal or anal penetration |

Limited Generalisation |

|

20 |

Manyike et al (2015) |

Quantitative Cross-sectional study Simple random Sampling |

Three secondary schools in Enugu and Ebonyi state.

South East Nigeria. |

506 adolescents Occupation: Secondary school students. Age: 10 to 24 years |

80 percent were educated by parents, majority by mother only (46.2%) and both parents (45.2%). 72.1% were not informed that family members and friends can sexually abuse them. 73.8% were not informed to report to adults if it happens to them. Conclusion: Adolescents educated by parents were 1.23 times less likely to be abused compared to non-educated adolescents. |

Non-in depth response |

|

21 |

Kunnuji & Esiet (2015) |

Quantitative

Questionnaire Convenient Sample |

Iwaya Community, Lagos State, South West Nigeria |

480 Adolescents girls Occupation: Out of school students |

Prevalent rate- 18% experienced coerced sex Statutory rape: 45% An association between age and experience of statutory rape |

Limited Generalisation |

|

22 |

Nwolisa et al. (2016) |

Case review

Retrospective analysis of medical records |

Mirabel Centre, Ikeja Lagos State South West

Nigeria |

153 cases of sexual assault

Age: under 18 victim

Occupation: Not mentioned |

148 out of 153 patients were victim of rape-96.7% There were 147 (99.3%) females and 1(0.7%) male.

Sixty-one (41.2%) knew their assailant(s) while 85(57.4%) did not know. While 101(68.2%) victims had achieved menarche, 47(31.8%) had not. In the rape of 67.6% of victims, no weapons were used while in 27% a weapon of some sort was used. |

Non-in depth response; Limited Generalisation |

|

23 |

Aborisade et al. (2017) |

Qualitative

Interview

Purposive sampling |

Ikoyi Prison Kirikiri Medium and Maximum Prisons

Ikoyi, Lagos state South West Nigeria |

29 perpetrator of child under 15 currently in prison

Occupation: Not mentioned

Age: Adult |

Majority of their victims are under 12 years old. Childhood sexual abusive experience is an indicator for abusive behaviour in adulthood. Excuses: (58.62%) stated “I did not know what I was doing” 13.79%- state of drunkenness 10.35 %- ignorance of the law of child age to give consent for sex. 3.45%- attributed it spiritual machinations. 19 offenders express remorse for their actions and acknowledge the harm caused to their victims. 8 offenders only feel remorse due to the impact of imprisonment on their families. 2 offenders claim innocence. |

Recall and response bias |

|

24 |

Nlewem & Amodu (2017) |

Quantitative study

Cross sectional study

Questionnaire |

Three secondary school

Aba zone, Abia State Nigeria, South Eastern Nigeria |

350 Student Female adolescent only Occupation: Students Age: 13 to 17years |

Prevalence 42.5% rate among age 13 to 15; 48.5% rate among 16–17year.

Female adolescents living with parent are two times less likely to be sexually abused, and female adolescents with separated or divorced parents are six times likely to be abused. |

Non- in depth narratives |

|

25 |

David et al. 2018 |

Quantitative Questionnaire Multistage sampling technique |

Mushin Community Lagos

South West Nigeria |

398 adolescents

Occupation: Not specified Age: 10–19 years |

The prevalence- 25.7% (Penetrative abuse- 7.5%, Forced sex- 46.2%) Type of sexual abuse: Kissing, touching private parts, flashing, showing pornographic magazine/films, took pictures of me naked, sexual intercourse Disclosure: 61% did not 34.4% disclosed Reason for Non-Disclosure: Social shame and guilt, and nothing would come of my telling. |

Reliability and validity problems |

|

26 |

Okeafor, Okeafor and Tobin-West (2018) |

Quantitative Case control study Systematic sampling |

University of Port- Harcourt Teaching Hospital in Rivers State, South-South |

304 (Case-152, Control – 152) Occupation: Non- specified Age: 18 to 60 |

Prevalence: 21.4% Exposure to CSA is associated with mental illness in adulthood (adjusted odds ratio = 3.11, 95% CI = [1.67, 5.82]). family functionality. |

Reliability and validity problems |

|

27. |

Olatosi et al. (2018) |

Quantitative Questionnaire Convenient Sampling |

Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos. Southwest |

179 respondents Occupation: Dentist Age: Adult |

Physical, sexual and emotional abuse and neglect were majorly identified as bruises behind the ears, 162 (90.5%); oral warts, 114 (63.7%); poor self-esteem, 158 (88.3%) and untreated rampant caries, 137 (76.5%), respectively. Only 12 (14.1%) of those who observed suspected cases reported to the social service |

Limited generability |

|

28. |

Oyekola & Agunbiade (2018) |

Mixed method Questionnaires Interview |

Ile-Ife and Modakeke Southwest Nigeria |

443 Adolescents Age: 9 to 20. 10 teachers |

Prevalence: 59.8% Management: Counselling, followed by inform parents or friends. Majority prefer to keep to self. Parents' negative involvement in their children's sexual issues suggests that child education, security, and strict punishments could help address the problem. |

Recall and response bias |

|

29 |

Sodipo et al. (2018) |

Case review |

Mirabel Centre, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital Lagos State Southwest |

2160 cases of rape

Three years case review |

Survivors: female 97.7%, Male: 2.3% Perpetrator: The majority of the perpetrators were known to the survivors with 10.3% being family members. Common form of abuse: Defilement (71.6%) Rape (20.3%). The majority of the referrals to the center were from the police (76.7%), while self-referrals made up 8% of referrals. |

Secondary data Reliability and validity problem |

|

30. |

Opekitan et al. (2019) |

Quantitative cross- sectional Questionnaire Purposive |

Twenty selected health facilities in Ogun state. Southwest Nigeria |

86 respondents

Occupation : Health workers |

A large percentage of health workers ( more than half) were unaware of any social infrastructure or hospital protocol for child abuse reporting. Many health workers lack awareness of social infrastructure or hospital protocol for reporting child abuse. Deliberate training is needed to help victims of child abuse. |

Small sample Limited Generalisation |

|

31 |

Uvere, and Ajuwon (2021) |

Quantitative Cross-sectional study Questionnaire Descriptive statistics, chi- square and logistic regression |

Selected market in Ibadan. SouthWest |

Female Adolescent hawker (FAHs) 410 participants |

69% of young female hawkers faced sexual abuse within 3 months prior to the study. Male customers, traders, and peers perpetrated most of the abuse. Shockingly, 67.5% of victims didn't seek help. To address this issue, interventions such as age-appropriate sexuality education and life-building skills should be targeted towards FAHs. Conclusion: Advocacy is also recommended for caregivers and market stakeholders. |

Recall and response bias |

summarises each of the 31 included studies. The majority of these studies were quantitative (n=20) and cross sectional. Only nine studies were qualitative [8,17,18] and two were mixed methods [19]. The majority of the studies were conducted in the Southwest (n=19), and only five were carried out in the Southeast. One was conducted in each remaining geographical zone except Northwest, where research on CSA was unavailable. A significant number of the studies were community- based (n=12). Nine studies were conducted in clinical settings, five in school settings, and only one study explored child sex offenders in prison [20]. Most of the studies collected data from children and adolescents, particularly girls. Very few explored the experiences of parents, community leaders, religious leaders, healthcare professionals, teachers and offenders, and none interviewed policy makers. Purposive and convenience sampling techniques were commonly used. Sample sizes ranged from 23 to 4000 participants [3,21].

Data collection: Data were collected using questionnaires(n=18). Most of these questionnaires were self-developed and considered the social lifestyle and factors that could predispose their participants to being sexually abused in childhood. Also, the age of onset was commonly elicited across the questionnaires, as was the relationship between the victims and the perpetrators. Some studies used only 6-item questionnaires while others used as many as 30 [22]. Other methods of data collection include in- depth qualitative interviews (n=5), and three studies used a mixed approach to data collection, which included questionnaires, in depth individual interviews and focus groups [19].

The prevalence and patterns of CSA

A wide variation in the prevalence of CSA in Nigeria was reported ranging between 2.1-77.7% [3,4] . Of the 31 included studies, 12 reported a higher prevalence of CSA in females [3]. Only one study, however, showed that more boys than girls experienced CSA as a child [3]. This discrepancy could be attributed to the difference in the number of females and male that participated, which was not clearly stated in this study. A variation in prevalence was observed depending on the group, for example, the prevalence of CSA was reported to be 70% among apprentices [22], 69.9% among girls selling goods on the street [23], 10% to 68% among teenagers attending secondary schools [24,25], and 35% in out-of-school children [26]. The most common age of first exposure was reported to be 12, and those under the age of 18 years were most likely to be victimised again within the next year [26].

Form of CSA reported

Common forms of CSA reported were unwanted kissing, hugging, inappropriate touch to breasts and genitals, verbal threats, abuse and rape [22,23,27]. In addition, teenagers were forced to look at pornographic pictures, films, videotapes or magazines, to watch perpetrators exposing genitals and masturbating, coerced into full sexual intercourse, or experienced rape and vaginal or anal penetration [16,25,28]. All the studies found that perpetrators were usually men, mostly known to the victims either as relatives, friends or neighbours. Only a few respondents were victims of stranger or gang rape. A few studies found that perpetrators used different forms of enticement such as money, gifts or food, alluring promises, shelter or accommodation to lure adolescents [22]. Common places reported for CSA by perpetrators known or related to the child were during times of being home alone with the child, watching TV with the child, or when they sent the child on an errand after gaining the parent’s trust. The most common places for unknown assailants to coerce the child into sexual activity were friend’s homes, familiar neighbourhoods, and during organised activities, such as parties [20]. One particular study, by [23], considered children respondents’ awareness of the risks associated with unprotected sex. 56.9% and 45.7% were unaware that such coercion could lead to unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, respectively. However, a significant percentage (31.5%) of girls that participated in this study claimed they bought self-prescribed medication at a pharmacy, after experiencing abuse. Most of the victims preferred to keep the experience to themselves, and few victims discussed their experience with friends and family members.

Causes of CSA in Nigeria

Twelve studies explored causes of CSA [18,29]. One study found that female adolescents living with their parents were less likely to be sexually abused than female adolescents with separated or divorced parents. Other factors that increased the chances of CSA included basic deprivation and living arrangements [26]. Several factors have been identified that increase the risk of child labour and exploitation practices, such as hawking and living separately from parents. Also, factors include being of a younger age range, specifically between 10 and 15 years old, consuming alcohol, having a disability, and experiencing labor and exploitation practices [18,24,29]. [23] however identified no significant relationships between the incidence of adolescent sexual abuse and socioeconomic class or age.

Additionally, research exploring teenagers’ perspectives has shown that the most common causes of CSA are poverty (52%), and cultural and religious practices (28%). Most children that participated in these studies in Nigeria suggested that their parents’ low socioeconomic status and inability to meet their financial needs subjected them to exploitative practices such as hawking, street begging, and seeking employment as house maids, which although appeared to solve their financial precarity, also indirectly exposed them to CSA [17] Beyond this, gender discrimination and the relative social invisibility of young females alongside prevailing societal norms that are supportive of sexual violence were identified as other causes of CSA in Nigeria [22,25,30]. The least-reported factors were physical appearance and lack of sex education. Two studies identified protective factors, such as the active involvement of parents and teachers in terms of early sexual education and raising awareness of CSA to girls [25].

Nigerianparents’ andvictims’ knowledge, perceptions and attitudes regarding CSA

Six studies explored participants’ knowledge, perceptions and attitudes, with emphasis on their sociocultural perspective and how this frames their standpoint regarding CSA. [29] Revealed that the majority (78.3%) of parent respondents had previous knowledge, as well as having heard about an incident involving their child or another child. Of these, merely 18.8% defined CSA as sexual intercourse with a child, either forcefully or consensually. Unfortunately, this study did not report how the remaining 80% of respondents defined CSA. The majority (84.2%) of the respondents agreed that CSA is common in their community; however, only (34.6%) agreed that CSA could have a serious health impact on victims. Only 2.1% of parents disclosed their children had experienced CSA and more than 90% of respondents claimed they discussed ‘stranger-danger’ with their children. Despite parental awareness, almost half of the respondents claimed their children could not be sexually abused; yet the authors subsequently note that over a quarter reported leaving their children unsupervised. The majority of respondents condemned CSA acts such as rape, date rape, gang rape, child prostitution, and incest; however, evidence of gender role stereotyping exists [19] and as a result, female gender rights are seen as an appendage to males, due to boy-child preferences in Nigeria. [29] Explored parents’ perspectives of practices that could contribute to CSA and found that respondents agreed they should sell their children to whoever can feed or properly educate them, especially in instances of extreme financial poverty. [18] Reported that victims of sexual abuse are frequently forced to marry their perpetrators, especially when the sexual abuse results in unplanned pregnancy. Sexually abused children who participated in this study claimed they did not disclose that they had been a victim of CSA to their parents. Instead 75% preferred to discuss their abuse with a friend. Others however found that some children still reported their experience of CSA with family members and friends. The number of parents who disclosed their child’s experience to the police, community leaders, or a healthcare professional was negligible. This may be due to the current trend in Nigeria, where victims are subjected to secondary victimisation by their parents, medical personnel, families, neighbours, and others [15,31]. The reviewed studies found that more efforts are required within the school system and at household and societal levels to curb, manage and reduce CSA. Victims must be referred for counselling and perpetrators must be severely punished [31]. These studies identified the strengths and gaps in parents’ knowledge, perceptions, and practices of CSA in Nigeria.

The impact of sexual abuse among adolescents in Nigeria

Among the 31 papers examined, only two studies predominantly focused on the immediate and long-term sequelae of abuse on adolescents, society, and the nation at large. These studies identified psychological consequences such as flashbacks, sleep disorders, guilt and self-blame feelings of powerlessness, distrust, and anger. Sixty-eight percent of young people explained that they were also victimised by their parents, medical personnel, families, friends, and neighbours. Participants claimed their experiences of CSA left them traumatised. Child respondents in this study affirmed that such traumatic experiences damaged their educational careers, reduced the country’s future workforce, and impaired their future contribution to economic development and thereby CSA created long standing negative impacts for their nation [17]. Consequently, it is evident that the effects of CSA have a far-reaching and devastating impact on the individuals and the nation as a whole.

Healthcare professionals’ knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes regarding CSA

Three studies focused on healthcare professionals and assessed their knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes about CSA. [30] Olatosi & colleagues assessed the knowledge of 175 Nigerian dentists on the clinical signs of CSA as being inadequate, and respondents reported a lack of a clear structure for referring victims to essential services. Despite being one of the specialists who attends to more children and is well placed to intervene, 46.5% of respondents do not evaluate suspected cases of abuse and neglect. When the dentists were asked how they responded to suspected cases of abuse, 65.4% reported a lack of knowledge about referral procedures and 57.5% were afraid of the consequences for the child. Findings from this study are consistent with research by [32], which assessed healthcare professionals’ level of awareness of the social and legal supports available for victims. Disturbingly, an overwhelming proportion of respondents in this study agreed they are unaware of the available social resources for victims. Additionally, the study shows that a majority of healthcare professionals lack adequate knowledge of referral procedures and were concerned about confidentiality issues, a predominant barrier to reporting suspicious cases of child abuse [30]. Despite theoretical knowledge, clinical inefficiency exists, which demonstrated knowledge gaps among healthcare professionals in recognising and responding to victims of sexual abuse, culminating in professional non-enquiry attitudes. On the other hand, research by [15] explored rape victims’ post-assault experiences and adjustment patterns, interviewed two medical doctors and two psychologists and collected experts’ opinions on the victimology of rape. Respondents from this study stated that victims’ reactions and recovery largely depend on a complex combination of individual characteristics (such as personality) and external factors (such as the victim’s social support network, victim-assailant relationship and severity of the assault). As, such factors have a great impact on a victim’s psychological functioning and adjustment process, it is important to focus on a victim’s individual experiences and their unique social contexts when assessing their reactions and recovery needs. This will ensure that victims are provided with appropriate and tailored support.

Identification and management of CSA cases in Nigeria

This review identifies studies that discuss the practice of identifying CSA victims in Nigeria. Research by explored teachers’ opinions and reported complexities surrounding the recognition of CSA. Symptoms that were noted were things like young people withdrawing from others, being sad or moody, displaying anxiety or seeming to be in pain and finding difficulty in carrying out daily activities. Studies suggest that primary prevention in contemporary Nigeria is based on parental supervision, child- parent communication about sexual activity and danger from strangers and familiar people, while secondary preventive practices include reporting to the police station and hospital for medical examination [29]. Unfortunately, authors reflect that discussions around sexual abuse seldom occur and parental supervision is neglected [29]. Also, this study revealed that although Nigerian parents can readily identify the immediate physical signs of CSA, they were often unable to recognise behavioural changes as potential indicators of CSA. Such unawareness about the range of symptoms associated with CSA may delay the needed response to protect the child from further abuse and seek treatment. In cases where abuse is identified, they are rarely reported as respondents believe disclosing such acts will only bring social stigma and more traumas for their child and family, rather than justice [19]. This is particularly challenging, as the parental response to CSA determines the child’s interactions with legal and health professionals, when seeking help following abuse. Of the 31 included studies, two focused on management of CSA [29]. Only 50% of victims from cases reviewed were subjected to routine High Vaginal Swabbing and retroviral screening, including for hepatitis B and C, and none received HIV and viral hepatitis post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), which is necessary to prevent them from being infected with the HIV virus. Out of the 60.7% cases reported to the police, none led to prosecution [29]. Antibiotics were only prescribed to 34% of the victims, with fewer prescriptions for analgesics, vitamins, counselling, and contraceptives; only three quarters of the victims were checked for sexually transmitted infections and a negligible number of victims were referred to post exposure prophylaxis, while none received the hepatitis B vaccine [29]. These studies reported that cases were reported between one hour and thirty days after occurrence of the abuse, generically managed, and not reported to the police. HCPs only come in contact with children when they are presented by the parent, guardian or teacher, and there are no structural systems in place to report abuse; most cases go unnoticed as there is no routine screening for child abuse among young girls in the Nigerian healthcare system. Previous studies have clearly identified that parents are less likely to report the sexual abuse of their child because of the social stigma and future consequences for the child; this suggests therefore that only a minority of CSA victims are referred for medical intervention.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to systematically aggregate empirical evidence and critically review the existing body of knowledge on CSA in Nigeria. Firstly, while general research on CSA has increased over the past two decades, studies focusing directly on CSA in Nigeria are still rare. This review highlights that limited research has been conducted on CSA in Nigeria. The majority of the reviewed studies were carried out using quantitative approaches, to explore the prevalence, experiences of CSA victims and HCPs [22,30]. Yet CSA experiences are complex and sensitive and using a quantitative approach can decontextualize the complexity of that experience. Some of the researchers that used clinical case studies seem not to be sensitive to the context, and the possible influences of this approach on the reliability and generalisation of these studies were not mentioned [29,8].

A majority of the studies predominantly focused on the prevalence and patterns of CSA. Only a few focused directly on the factors responsible and little effort had been made to examine the current clinical patterns of management. Only two focused on the knowledge and awareness of healthcare professionals (HCPs) and none focused on the challenges faced in identifying and responding to a victim of CSA. None of these studies directly explored young people’s and adults’ perceptions about children’s status in society and the association with CSA. Therefore, it is clear that more research needs to be done to fully understand the extent of CSA in Nigeria.

According to this review, there are disparities in published statistics across the country concerning CSA, and the actual magnitude of the dilemma remains unknown. For the development of prevention strategies and policy initiatives, it is crucial to have accurate data on the magnitude of CSA. Despite growing evidence of the size of the problem, current evidence comes largely from institutionalised settings, and only few used community-based samples. Another concern is the diverse and varied terminology employed and variation operation definition of the constructs of CSA used by researchers and research methodologies limit the extent to which comparisons can be made between studies [33]. The current review showed definitional ambiguities, the heterogeneous nature of victims and perpetrators, and the rapidly changing nature of sexual activities have masked the true scale of this crime. This review also found that discrepancies and wide variation in the prevalence of CSA in Nigeria could be attributed to the gender of participants, i.e. the number of males and females and the use of broad terminology rather than a specific definition of one of the named types of abuse. A definition of CSA in general, but most importantly, a distinction between types of sexual abuse, is obvious. Future research should develop a universal definition and language for CSA, as well as a clear distinction between types.

This review highlights that children are at a higher risk of experiencing sexual abuse due to socio-cultural norms and their parents’ low socioeconomic status. However, several studies from other countries have identified potential vulnerabilities and indicators that increase the risk of child sexual exploitation and concluded that these risks apply to all children, regardless of their gender, ethnicity, cultural background, or socioeconomic status [34,35]. This means that having a reductionist approach to theorising the predisposing factors to CSA may affect the development and implementation of practice and policies to safeguard children identify and respond to victims of CSA.

This review showed that CSA entails short-term and lifelong sequela for the individual, family and society, especially if left unrecognised or untreated [12,36]. Early trauma suffered by sexually abused children has been linked to multiple behavioural, psychiatric and mental problems, including substance abuse, anxiety and depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide attempts [36,16]. This field requires further research given the high prevalence of CSA in Nigeria and the severe effects it has on victims’ well-being, as well as the restrictive challenges professionals face in safeguarding them Ifayomi. The harmful and sociocultural practice, taboos and shared norms and values remains a major predictor for CSA in Nigeria and barriers to disclosing and seeking help. Despite the parental awareness, almost half of the respondents claimed their children could not be sexually abused also left their children unsupervised. Hence parents’ perspectives, practices, and attitude could also contribute to CSA.

Radical services and approaches are in place for the protection and social welfare of children and the prevention of CSA. This approach is contrary to the current situation in Nigeria, where the quality of medical and psychosocial care provided to survivors of CSA remains poorly studied and has proved to be substandard compared to the required care for victims. There is still a substantial gap between the medical services provided to victims of CSA and their healthcare needs [20,29] and HCPs expressed their frustration as their efforts remained unproductive. There is need for more research on CSA in Nigeria regarding the predisposing factor, available service for victims and family, and professional practice of supporting sexually abused children in Nigeria. Summaries of critical findings and implications are included in Table 3 and 4.

Table 3; Critical Findings

|

The risk and vulnerability factors that increase acts of sexual violence and abuse against children include basic deprivation, extended living arrangements, younger age (child aged 10 to 15 years), alcohol consumption, disability, child labour, and exploitation practices, such as hawking. Prevailing societal norms cause gender discrimination and social invisibility. Active involvement of parents in sexual education and orientation of girls on CSA are good protective factors. |

|

Parents can readily identify the immediate physical signs of CSA, but they are unable to recognise behavioural changes as indicators, such unawareness may delay the needed response to protect the child from further abuse and seek treatment |

|

Psychological consequences such as flashbacks, sleep disorders, a sense of guilt and self-blame, emotional numbness, the feeling of personal powerlessness, a sense of distrust, and anger. Victims were found to be left traumatised with unsavory memories which tend to truncate psychosocial development. Impacts of experiencing traumatic experiences damage their educational career, reduce the country’s future workforce, and impair their future contribution to economic development |

|

Professionals were not confident in addressing cases and limited knowledge on knowledge of referral procedures and identifying cases. |

|

There existing care for sexually abused children remains substandard, as there is a wide gap between the available structures of CSA management and the care the victims require. |

Note. A summary of critical findings from current systematic review

Table 4: Implications of the Review for Practice, Policy, and Research

|

Practice |

Low level of the society awareness on CSA, common practice and perception and available substandard healthcare suggest professional knowledge, perception of their roles and evaluation of care provided for sexually abused children is warranted |

|

Policy |

The enormous magnitude of the problem and existential dimensions of CSA related professional services demands that policymakers develop and implement all-encompassing child-oriented policies, and child and family-focused practices. |

|

There is a need for urgent and comprehensive context-based and culturally sensitive national guidelines for HCPs working with sexually abused children in Nigeria |

|

|

Research |

Most research conducted in Nigeria on CSA has been quantitative, CSA experiences are not only complex and sensitive, but subjective in nature, and using a quantitative approach decontextualises the complexity of that experience. There is a need to conduct rigorous studies that explore how Nigerian define CSA, and the personal meaning the victims of this crime attributed to it and to examine their attitudes toward CSA |

|

There is a need to conduct phenomenological qualitative studies to understand society’s perceptions, attitudes, and victims’ experience of CSA. Such empirical evidence can then be utilised to develop culturally specific, and context-oriented instrument quantitative studies |

|

|

There is an urgent need to explore those factors undermining professional practice of supporting sexually abused children and develop a context-based national guidelines. |

Strengths and Limitations

This review examines the prevalence of CSA in different samples, and highlights the magnitude of CSA in Nigeria and the types of CSA that are most commonly experienced in the Nigerian context. In addition, the study examined the factors influencing children’s vulnerability to sexual abuse in Nigeria. Empirical evidence reveals patterns of CSA and society’s perceptions and awareness of CSA and its devastating consequences for victims, their families, and wider society. Such evidence is necessary to develop a framework for context-oriented preventative programmes in Nigeria. Additionally, these results increase our understanding of available services and the gaps in literature for further research. It provides implications for public health policies and interventions and calls for the need to strengthen legal frameworks and to improve the system of reporting and responding to cases of CSA. Finally, it emphasizes the need for further research on CSA in Nigeria. The critical appraisal of these studies also helped to assess the quality and quantity of studies conducted in Nigeria on this topic. A broad perspective has been offered on empirical research in CSA in Nigeria because the review has not been limited to any one research design or methodology (meaning all design, either quantitative, qualitative and mixed method approach studies are included). The review is limited by the fact that we only included studies published between 1999 and 2022 in peer-reviewed journals and published in English. It is possible that some studies, which were published in non-indexed journals or non-published for some reasons such as dissertation or thesis, are not identified and included. In selecting the studies for inclusion in the review, we ensured only studies representing independent samples and only those that explored CSA were included, others that explored other forms of child abuse and exploitation were excluded, therefore, may impact the overallfindings and may present an underestimate of the prevalence of CSA. Also, this review was conducted to gather information about the Nigerian context, and so the data is specifically related to the West African context. Please take into account these limitations when considering the results of the review.

We considered the diverse characteristics of the studies included in this analysis, particularly the participant demographics, topics explored, and context. Studies explored a wide range of CSA areas, including prevalence and contributing factors, parents’ perceptions of CSA, management of CSA and support for CSA victims. The studies included in this review were conducted across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones, although most are published from a particular zone, the Southwest. Aggregating evidence from all zones and cultures across the country helped the researchers explore different perspectives and cultures, identify the uniqueness among people from diverse backgrounds, and understand how these factors influence their behaviours, attitudes and values. We believe this is critical for developing more effective and culturally sensitive interventions, policies, and services to meet the needs of different victims and their families. On the other hand, the lack of evidence on CSA from other geo-political zones has serious ethical consequences for our review findings and limits generalizability, especially for victims in rural areas.

Lastly, comparing the results from this systematic review with [37], a systematic review of 20 articles published between 2005 and 2016 on child sexual abuse in Nigeria helps to highlight the progress made in the field and areas that still warrant attention. In 2020, Okunola and colleagues made observation that most of the available studies were clinically reported cases of CSA, however this reviews shows that effort has been made by researchers to start conducting community based research, exploring the victims experience and society’s perspectives and practices around CSA, including perpetrator opinions and perceptions. However, many gaps in the research have not been examined. There is a need to exclusively examine the current services available to victims of CSA in Nigeria. Additionally, there remains a substantial lack of research that focuses on the challenges facing healthcare professionals in supporting CSA victims in Nigeria. By understanding this, a more context- oriented approach, procedure, and policy that caters for the needs of victims,

Implication for further study

Our review revealed that there are critical implications for further research in terms of research methodological approaches, aspects of the CSA subject explored, research samples and implications for practice. Most research conducted in Nigeria on CSA has been quantitative, there is a need to conduct rigorous studies that explore how Nigerians define CSA, and the personal meaning the victims of this crime attributed to it and to examine their attitudes toward CSA. There is a need to conduct qualitative studies to understand societal perceptions, attitudes, and victim experiences of CSA. Such empirical evidence could then be utilised to develop culturally specific and context-oriented quantitative studies. Similarly, no empirical work has been conducted to explore how healthcare professionals can help prevent CSA, raise awareness, and help victims emotionally and socially. Since disclosure is essential in initiating medical, psychosocial and legal intervention for children who have been sexually abused, there is a need to explore the disclosure process, as well as barriers and facilitators from the perspectives of victim family and professionals. Lastly, since the available healthcare services for sexually abused children in Nigeria are still developing and therefore sometimes ineffective compared to the comprehensive care required by these victims, there is need to explore the way healthcare professionals perceive and understand their roles and the associated issues and challenges undermining their effort from their own point of view is necessary.

CONCLUSION

Despite receiving increasing attention, CSA remains a severely and extremely detrimental epidemic. The magnitude of CSA in Nigeria remains unknown, with disparities in published statistics across the country. The socio-cultural norms, including traditional practices and the low socioeconomic level of parents, increased the child’s vulnerability to sexual abuse and prevented them from disclosing the abuse. The quality of medical and psychosocial care provided to survivors of CSA remains poorly studied and has proven to be substandard compared to the required healthcare for victims. Even though the detrimental impact of CSA on victims is getting more attention around theworld, professionals in Nigeria struggle to develop effective practices, services, and policies. Therefore, it is recommended to define CSA legally, develop a consensual conceptual framework, and increase awareness of CSA. The process of reporting and responding to children who have been sexually abused in Nigeria must also be improved.

REFERENCES

1.Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. World Health Organisation Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation Press. 2006.

2.The economic burden of violence against children. Analysis of Selected Health and Education Outcomes Nigeria Study. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Funds. 2015.

3.Obisesan A, Adeyemo R, Onifade K. Childhood sexuality and child sexual abuse in southwest Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999; 19: 624- 626.

4. Audu B, Geidam A, Jarma H. Child labor and sexual assault among girls in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009; 104: 64-67.

5. Pereda N, Guilera G, Forns M, Gómez-Benito J. The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009; 29: 328-338.

6. Smallbone S, Marshall W L, Wortley R. Preventing child sexual abuse: Evidence, policy and practice. Oregan, USA: Willan Publishing. 2013.

7.Martinello E. Applying the ecological systems theory to better understand and prevent child sexual abuse. Sexuality and Culture. 2020; 24: 326-344.

8.Sodipo OO, Adedokun A, Adejumo AO, Oibamoyo O. The pattern and characteristics of sexual assault perpetrators and survivors managed at a sexual assault referral centre in Lagos. Afr J Primary Health Care Fam Med. 2018; 10: e1- e5.

9. Melrose M. Twenty-First Century Party People: Young People and Sexual Exploitation in the New Millennium. Child Abuse Review. 2013; 22: 155–168.

10. Coy M. ‘Moved around like bags of rubbish nobody wants’: How multiple placement moves can make young women vulnerable to sexual exploitation. Child Abuse Review. 2009; 18: 254–266.

11. Ellis. K. Blame and Culpability in Children’s Narratives of Child Sexual Abuse. Child Abuse Rev. 2019; 28: 405–417.

12. Hornor G. Child sexual abuse: Consequences and implications. J Pediatr Health Care. 2010; 24: 358-364.

13. Warrington C with Beckett H, Ackerley E, Walker M, Allnock D. Making Noise: Children’s Voices for Positive Change after Sexual Abuse. University of Bedfordshire. 2017.

14. Sigurdardottir S, Halldorsdottir S, Bender SS. Consequences of childhood sexual abuse for health and well-being: Gender similarities and differences. Scand J Public Health. 2014; 42: 278-286

15. Aborisade RA, Vaughan FE. The victimology of rape in Nigeria: Examining victims’ post-assault experience and adjustment patterns. African Journal for the Psychological Studies of Social Issues. 2014; 17: 140-155.

16. Okeafor CU, Okeafor IN, Tobin-West CI. Relationship Between Sexual Abuse in Childhood and the Occurrence of Mental Illness in Adulthood: A Matched Case–Control Study in Nigeria. Sexual Abuse. 2016; 30: 438-453.

17. Oteh CO, Ogbuke MU, Iheriohanma EBJ. Child abuse as a setback on nation building: a study of Ezza community in Ebonyi state, Nigeria.International Journal of Development and Management Review. 2009; 4: 86-95.

18. Aderinto AA. Sexual abuse of the girl-child in urban Nigeria and implications for the transmission of HIV/AIDS. Gender and Behaviour. 2010; 8: 2735-2761.

19. Ogunyemi B. Knowledge and perception of child sexual abuse in urban Nigeria: Some evidence from a community-based project. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2000; 4: 44-52.

20. Aborisade RA, Adeleke OA, Shontan AR. Accounts, excuses and apologies of juvenile sexual offenders in selected prisons in Lagos, Nigeria. AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities. 2018; 7: 85-97.

21. Ashimi AO, Amole TG, Ugwa EA. Reported sexual violence among women and children seen at the gynaecological emergency unit of a rural tertiary health facility, northwest Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015; 5: 26-29.

22. Ajuwon A, Olley BO, Akin-Jimoh I, Akintola O. Experience of sexual coercion among adolescents in Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2001; 5: 120-131.

23. Ikechebelu JI, Udigwe GO, Ezechukwu CC, Ndinechi AG, Joe– Ikechebelu NN. Sexual abuse among juvenile female street hawkers in Anambra State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008; 12: 111-119.

24. Envuladu EA, Umaru RJ, Banwat ME, Lar LA, Lassa S, Zoakah AI. Sexual abuse among female secondary school students in Jos, North central Nigeria. Journal of Medicine in the Tropics. 2013; 15: 9-12.

25. Manyike PC, Chinawa JM, Aniwada E, Udechukwu NP, Eke CB, Chinawa TA. Impact of parental sex education on child sexual abuse among adolescents. Nigerian journal of paediatrics. 2015; 42: 325- 328.

26. Kunnuji MO, Esiet A. Prevalence and correlates of sexual abuse among female out-of-school adolescents in Iwaya Community, Lagos State, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2015; 19: 82-90.

27. Abdulkadir I. Musa HH, Umar LW, Musa S, Jimoh WA, Aliyu Na’uzo M.Child Sexual Abuse in Minna, Niger State Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal. 2011; 52: 79–82.

28. David N, Ezechi O, Wapmuk A, Gbajabiamila T, Ohihoin A, Herbertson E, Odeyemi K. Child sexual abuse and disclosure in South Western Nigeria: a community based study. Afr Health Sci. 2018; 18: 199-208.

29. Fawole OI, Ajuwon AJ, Osungbade KO, Faweya OC. Prevalence and nature of violence among young female hawkers in motor-parks in south-western Nigeria. Health Education. 2002; 102: 230-238.

30. Olatosi OO, Ogordi PU, Oredugba FA, Sote EO. Experience and knowledge of child abuse and neglect: A survey among a group of resident doctors in Niger . Niger Postgrad Med J. 2018; 25: 225-233.

31. Ebuenyi ID, Chikezie UE, Dariah GO. Implications of silence in the face of child sexual abuse: observations from Yenagoa, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2018; 22: 83-87.

32. Opekitan AT, Bolanle F, Olawale O, Olufunke A. Awareness of social infrastructures for victims of child abuse among primary health Workers in Ogun State, Nigeria. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2019; 40: 23-28.

33. Mitchell K, Moynihan M, Pitcher C, Francis A, English A, Saewyc E. Rethinking research on sexual exploitation of boys: Methodological challenges and recommendations to optimize future knowledge generation. Child Abuse Negl. 2017; 66: 142-151.

34. Davies EA, Jones AC. Risk factors in child sexual abuse. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013; 20: 146-150.

35. Wodarski JS, Johnson SR. Contributing factors to child sexual abuse. Evidence-Informed Assessment and Practice in Child Welfare. 2015; 53-65.

36. Mullers E, Dowling M. Mental health consequences of child sexual abuse. Br J Nur. 2008; 17: 1428-1430.

37. Okunlola OB, Gesinde AM, Nwabueze AC, Okojide A. Review of Child and Adolescent Sexual Abuse in Nigeria: Implications for 21st Century Counsellors. Covenant Int J Psychol. 2020; 5.