Comparative Review of Global Incarceration Systems: A Human Centered Perspective

- 1. Women’s Health Institute, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (RWJMS), USA

- 2. Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, USA

- 3. New Jersey Reentry Corporation, USA

Abstract

This article explores how various countries structure their incarceration systems, focusing on their balance between punishment and rehabilitation. Drawing on examples from Norway, the Netherlands, Japan, and Spain, it evaluates different models through the lens of human dignity, public safety, and reintegration. The paper also addresses the systemic challenges in the U.S. prison system and considers what lessons can be adapted globally. By comparing philosophies and practices, this article underscores the importance of designing justice systems that foster transformation of character rather than perpetuate cycles of incarceration.

Keywords

• Incarceration systems; Prison reform; Criminal justice; Rehabilitation; Recidivism; Human rights in prisons; Comparative justice systems; Correctional policy; Reintegration; Restorative justice; Community based sentencing; Penal systems; Prison conditions; Sentencing reform; Mass incarceration; U.S. prison system; Social reintegration; Alternatives to imprisonment; Correctional models; Global justice reform; TBS.

Citation

Shabbir MA, Bachmann G, McGreevey JE (2025) Comparative Review of Global Incarceration Systems: A Human-Centered Perspective. JSM Sexual Med 9(4): 1165.

INTRODUCTION

Crime is a universal reality, but how nations respond to it varies, reflecting not only policy diversity but also cultural identity, social justice, and political will [1,2]. Countries like Norway and the Netherlands have invested in human based incarceration systems that emphasize reintegration, education, and restorative justice [3]. Japan and the United States have focused on incarceration systems that emphasize discipline, deterrence, and control [4,5].

All incarceration systems do not achieve the same outcomes [6]. Some are successfully reducing crime, improving public safety, and allowing successful reentry into their communities [2-5]. Others drive recidivism cycles, amplify social injustice, and burden public finances [7]. To contrast them is important, as it informs societies as to which policies are possible and indicates scalable models with human rights and community welfare dividends [8]. Through the observation of international success and failure, policymakers can learn from failures and apply best practices to suit their own cultural and legal environments [8].

This paper examines these international contrasts, in order to explore what makes justice systems truly effective, their ability to transform lives, reduce recidivism, and strengthen communities. This review aims to inform future reform efforts, particularly in the U.S, where mass incarceration remains a deeply entrenched crisis and to discuss one program, under the auspices of the non-profit NJ Reentry Corporation, that is making great strides in reducing recidivism [8].

Understanding Incarceration

Incarceration is a complex issue that affects nearly every part of society [9]. While being imprisoned takes away a person’s liberty, the most basic human right, it also strips them of other rights [10]. People in prison deserve access to healthcare, fair treatment, protection from abuse, education, and the ability to maintain some level of dignity [11]. Whether or not those rights are honored depends on a country’s laws, resources, and values.

Prison management reflects that specific region’s cultural and societals values [1]. When a system emphasizes humane treatment, rehabilitation, and second chances, it tends to improve outcomes: lower recidivism,more successful reintegration, and less long-term burden on the system [12]. But when prison conditions are harsh, resources are limited, and punishment is the major goal, it often leads to more crime [7]. Most individuals come out of prison more isolated, less employable, and with fewer chances to build a new life [13] (Table 1).

Table 1: International Comparison of Reentry Programs, Recidivism Rates, and Key Features [14-18].

|

Country |

Reentry Program Example |

Recidivism Rate |

Key Features |

|

Norway |

Holistic Rehabilitation Model |

~20% |

Education, vocational training, mental health support |

|

Canada |

Circles of Support and Accountability |

Reduced by 70% (sexual offenses) |

Community-based support for high-risk offenders |

|

Australia |

Prison Education Programs |

9% reduction |

Educational opportunities during incarceration |

|

New Zealand |

Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court |

62% reduction |

Specialized courts focusing on rehabilitation |

|

United States |

Limited Reentry Support |

~68% |

High recidivism due to lack of structured programs |

Well-functioning prisons and jails serve everyone [19]. They reduce strain on public budgets by lowering reoffending rates [20]. They help build a workforce by giving people skills and training while they serve their time [21]. They contribute to safer communities by making sure people leave prison more stable and better supported than when they were at the start of their sentence [14].

It is critical to evaluate incarceration systems by looking at measurable outcomes: How often do people end up back in prison? Are they looking for jobs afterward? Is crime going down? Are families staying together? These questions help to decide whether a system is truly fulfilling its purpose, or just warehousing people [22].

Norway

Guided by a commitment to upholding human dignity and reducing recidivism, Norway’s justice system underwent a transformative shift in the 1990s, redefining imprisonment as a rehabilitative measure and implementing bold reforms: eliminating Ife sentences and capping maximum sentences at 21 years [23-29]. The idea was not to ignore justice but to shift the focus toward helping people reintegrate into the society as a productive member rather than return to crime, recidivism rates have dropped from around 70% to under 20% as of 2022, showing that when people are treated with dignity, they are more likely to rebuild their lives [23-27].

This approach, however, is costly [24]. Norway spends close to $93,000 per prisoner each year [23-26].The financial investment however has lower the crime rate, and created a more just and balanced society [25 29]. Two of its best-known facilities, Halden and Bastoy, exemply these results [23].

Halden Prison gives each inmate their own room with a restroom, a window to the outside, and a TV. There is a gym, a library, even a music studio. The aim is not luxury, it is normalization [28].

Bastoy Prison enhances these conditions. Located on an island, it has no fences. Prisoners farm the land, attend classes, and take part in community life [31]. They can have visits with their families and take part in drug rehab and violence prevention programs. There is a strong feeling of trust and autonomy, which builds a sense of responsibility and self-worth [30]. These reforms show that treating people like respected humans, can make a real difference [32].

The Netherlands

The Dutch approach to incarceration puts rehabilitation at the corner [36,37]. Instead of defaulting to jail time, the system often relies on community service, fines, and behavioral support for nonviolent offenses [32-37]. The goal is to avoid prison where possible and if incarceration is necessary, to prepare people for reentry when incarceration is necessary [38].

Prisons in the Netherlands are designed to look and feel like the outside world [31]. This helps inmates maintain their dignity and stay connected to their families and communities [31].

An innovative aspect of the Dutch penal system is the “walking convict” model, which allows certain low-risk offenders to serve their sentences with greater flexibility. Rather than immediate incarceration after sentencing, these individuals are permitted to return home while awaiting official instructions specifying the date and location of their imprisonment [39]. This scheduling flexibility enables offenders to align the start of their sentence with personal or professional obligations, such as choosing to serve during vacation periods to minimize the risk of losing job [39]. The facilities designated for these sentences are typically small scale, low security institutions that prioritize rehabilitation and social reintegration [33 39].

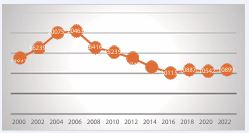

The country also invests in psychological rehabilitation [33]. Offenders with severe personality disorders can be detained in special forensic psychiatric institutions (TBS hospitals- meaning ‘at the disposal of the government’) after having served their prison sentence [35]. Since 1928, the Courts in The Netherlands have had the option to impose a combination verdict on offenders with severe mental disorders: a prison sentence and a penal hospital order – the ‘TBS’. The main aims of this penal hospital order are protection of society and treatment of the offender, in order to rehabilitate patients into the community [33 35]. As part of this supervised reintegration process, GPS tracking helps ensure safety while offering more freedom than full incarceration [40] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Netherlands Prison population [41].

There are concerns regarding the consequences of prison facility closures [42]. In recent years, the Netherlands has closed several prisons due to declining incarceration rates, which has led to the consolidation of remaining facilities into fewer, larger institutions [42,43]. This geographic concentration can create logistical and relational barriers for inmates and their families, particularly those living in rural areas [43]. Relocating offenders away from their home communities can weaken local reintegration networks, employment services, community-based treatment providers, and social support systems. These structural shifts risk undermining the rehabilitation and community reintegration objectives that the Dutch system seeks to advance [42]. The walking convict program also raises safety questions if not carefully managed [36]. Yet, the system is still a strong example of long-term thinking over short-term punishment.

Japan

Japan’s prison system is deeply influenced by its cultural emphasis on discipline, order, and personal responsibility [44]. The country has very low crime and incarceration rates and its correctional facilities run with tight structure and precision [44,45].

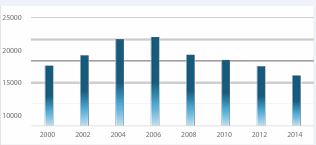

Rehabilitation here manifests by helping inmates learn topics from carpentry to leatherwork to computer programming. Inmates are ranked by behavior, and those who comply and improve earn privileges [46]. Some inmates can even leave for day work or family visits, offering a bridge between prison and society [46] (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Number of prisoners per 100000 people [51].

Critics of Japan’s model have raised concerns about the harshness of the environment. Inmates must follow strict rules governing even how they walk and dress. Social interaction is limited [48]. Unsentenced prisoners get one to two twenty to thirty minutes visits weekly; sentenced prisoners are entitled to only one fifteen-to-twenty minutes visit a month [47,48]. These visits are conducted in special rooms in the presence of a monitoring officer who takes notes of conversations, the visitor is separated by a partition and there is no provision for physical touch [48]. Solitary confinement is a common disciplinary measure, accounting for 85% of all disciplinary sanctions as of 2018 [49]. Reports from international organizations like The Amnesty International has raised concerns about cruel, degrading and inhumane treatment and its long lasting and debilitating effects on mental and physical health of prisoners [50]. While Japan’s low recidivism is metrically effective, the system’s human toll is harder to measure [46].

Spain

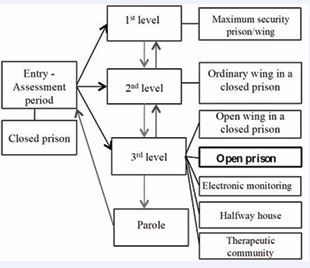

Spain’s model blends structure with compassion [53]. Prisoners are categorized into three levels based on the severity of their crimes, with different freedoms and responsibilities at each level [52]. Those closer to reentry have more interaction with the outside world and access to programs that prepare them for life after prison [52-54] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Classification of prisoners in Spanish prison system. [55].

One powerful incentive Spain offers is sentence reduction for prison labor, two days off their sentence for every day worked [14-54]. There is also the option of temporary leave for family or medical reasons [55]. For low-risk offenders, laws have been adopted which provide alternatives to incarceration and are divided into categories of suspension or or substitution. are common [54,55] (Table 2).

Table 2: Overview of Alternative Sentencing Measures in Spain According to the Penal Code and Royal Decree 840/2011 [56].

|

Measure |

Legal Reference |

Conditions & Details |

|

Suspension |

Penal Code Articles 80–87 + Royal Decree 840/2011 |

For sentences up to 2 years (first- time offenders) Available for inmates with incurable serious illness Up to 5 years if drug-dependent and enrolled in detox programs |

|

Substitution |

Penal Code Articles 88–89 + Royal Decree 840/2011 |

1.Fine: Up to 1-year sentence, 1 day prison = 2 fine units 2.Community Service: Up to 1 year, 1 day prison = 1 day work 3.Permanent Location (House Arrest): Up to 6 months, 1 day prison = 1 day home confinement 4.For Foreigners: Up to 6 years, expulsion and 5–10-year re-entry ban, after reaching third degree and serving ¾ of the sentence |

Spain’s Social Insertion Centers are an exemplary feature of the system. These facilities give inmates training and support before fully reentering society. Aranjuez Prison takes a family-first approach, offering special units where parents can live with their children and maintain family bonds [14].

Comparative Reflections

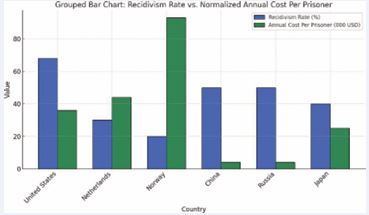

A comparative analysis of international incarceration systems reveals that countries emphasizing rehabilitation tend to achieve more sustainable public safety outcomes than those centered on punishment and control [1]. Norway invests approximately $93,000 per prisoner annually and maintains a recidivism rate of about 20% [14]. This investment is directed toward education, mental health services, and vocational training, which aims to prepare incarcerated individuals for successful reintegration into society [14]. While the cost is significant, the social benefits, including lower reincarceration rates and improved communal stability, suggest a favorable return on investment [14]. The United States presents a stark contrast. With lower per inmate expenditures, it experiences a recidivism rate of 68% within three years of release [25]. This rate is attributed to the system’s limited access to rehabilitative services, overcrowded facilities, and policies that prioritize incapacitation over reintegration [25]. Spain and the Netherlands have adopted community-based alternatives to incarceration, such as suspended sentences, community service, and electronic monitoring [33-56]. These measures aim to reduce prison overcrowding and maintain community ties [33-56]. Data from the Netherlands show a moderate recidivism rate of approximately 30% over five years, while Spain reports 30% over 4 years [33-56].

This relationship between spending, policy, and outcomes can be visualized through international comparisons of recidivism rates and prison costs [1,14,25,33,56] (Figure 4)

Figure 4 Cross country comparison of Recidivism rate and annual cost/prisoner [1-56].

This figure illustrates that higher investment in rehabilitation, as seen in Norway, correlates with lower reoffending rates, whereas incarceration systems with lower investment, like the United States, report higher recidivism rates.

Data on reimprisonment further validates these patterns.

Table 3: Reimprisonment Rates Across Countries [24].

|

Country |

1 Year |

2 Years |

3 Years |

4 Years |

5 Years |

|

Australia Austria |

45% |

|

47% |

|

|

|

Belgium |

|

|

62% |

|

|

|

Brazil |

|

|

43% |

|

|

|

Canada (Quebec) Iceland |

6% |

28% |

43% |

|

49% |

|

Ireland |

27% |

39% |

45% |

|

49% |

|

Israel |

34% |

|

38% |

|

41% |

|

Jamaica |

30% |

|

|

|

|

|

Japan |

9% |

|

|

|

|

|

Malta |

12% |

25% |

|

|

|

|

New Zealand |

32% |

|

43% |

|

|

|

Norway |

17% |

22% |

27% |

|

30% |

|

Philippines |

18% |

|

|

|

|

|

Scotland |

48% |

51% |

53% |

|

|

|

South Korea |

|

|

25% |

|

|

|

Spain (Catalonia) |

30% |

|

30% |

|

|

|

Switzerland |

26% |

|

|

|

|

|

Thailand |

35% |

|

|

|

|

|

United States (23 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

states) |

23% |

32% |

37% |

|

|

|

United States (21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

states) |

20% |

32% |

39% |

43% |

46% |

The Table 3 shows that countries like Norway, Japan, and Iceland maintain low recidivism rates over five years, while Belgium, Austria, and the United States record higher rates. Japan’s low recidivism rate, 9% over two years, appears effective; however, its highly restrictive environment, characterized by limited social interaction, solitary confinement, and monitored family visits, raises concerns about the long-term psychological impact on individuals leaving the system.

Recent research by Dahl and Mogstad (2020), published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, provides support for rehabilitative incarceration. Their study on Norway’s prison system demonstrates that incarceration coupled with rehabilitation reduces the likelihood of reoffending within five years by 27% and decreases the average number of subsequent criminal charges by 10%. These outcomes are not solely the result of incapacitation but reflect the impact of educational and vocational programs delivered during incarceration.

These cross-national comparisons and empirical findings suggest that rehabilitation-oriented incarceration systems offer more effective long-term solutions to crime reduction. The data also emphasizes the need for comprehensive reentry programs and community-based alternatives to imprisonment. While no single model is universally applicable, the success of countries like Norway provides scalable examples of how justice systems can reduce recidivism and promote social reintegration [14].

The New Jersey Reentry Corporation (NJRC), a non profit organization, is one template of an organization that is addressing the comprehensive needs of reentry individuals. The main purpose of NJRC is to provide all necessary services to those who are reentering their community after incarceration [57]. NJRC serves as an example of applying global best practices such as comprehensive reentry services and health interventions within the U.S. context [57]. This demonstrates the feasibility of scaling similar models nationwide [57]. NJRC provides a wide range of coordinated services, including employment training, addiction and mental health treatment, and legal and administrative assistance to help participants navigate government systems [57].

Additionally, NJRC fosters community engagement through support groups and outreach initiatives. These combined services create a supportive macroenvironment that serves as a practical platform for successful reentry [58]. NJRC reports a recidivism rate of 10%, compared to New Jersey’s statewide rate of 29.2% and the national average of nearly 68% within three years of release [59]. The organization’s recidivism rate of 19.7% further highlights its effectiveness in reducing repeat criminal behavior. NJRC has trained 3,367 program participants in financial literacy, computer fundamentals, and workplace readiness, while 1,737 participants have earned industry recognized skill credentials [59]. These integrated services illustrate how targeted, evidence-based reentry programs can successfully address the complex challenges faced by returning citizens, helping them reintegrate into society and reduce their likelihood of returning to prison [58,59].

Challenges and Considerations

Incarceration systems that prioritize rehabilitation encounter practical, financial, and political barriers that limit their broader adoption [25]. Expansive rehabilitative and reentry programs require substantial financial investment [25]. Although such strategies have demonstrated long- term benefits in reducing recidivism and supporting reentry, their cost presents challenges for countries with large prison populations [25]. In the United States, the cost of incarcerating one individual ranges from $33,000 to over $70,000 per year, with California reporting $133,000 per inmate annually. In contrast, rehabilitative programs average around $5,000 per participant, and expanding such programs could save billions of dollars [60]. However, most state budgets continue to favor incarceration over rehabilitation, limiting the potential for large scale reform. Brazil faces similar challenges where Association for the Protection and Assistance of the Convicted (APAC) model operates at nearly half the cost of state run prisons and shows lower recidivism rates. Its reliance on community involvement has restricted its nationwide scaling. Brazil’s broader prison system continues to suffer from overcrowding and a recidivism rate of around 70%, with limited resources directed toward rehabilitative initiatives [61].

Public and political resistance further complicate reform efforts. High profile crimes often drive public demand for harsher sentencing. This has been observed in the adoption of mandatory minimum sentences in the United Kingdom and “three strikes” laws in the United States, both of which were introduced in response to public pressure following violent crimes [62,63]. Despite limited long-term benefits, these policies gained political momentum, reflecting the influence of public perception over evidence-based reform [62] Cultural and political structures shape rehabilitation focused models. United States face the also challenge of policy fragmentation, with significant variation in criminal justice practices across states. This decentralization makes national level reform difficult to achieve [63]. Similarly, culturally specific models, such as Japan’s discipline focused system, may not align with societies that prioritize individual freedoms and rights. Even successful programs remain politically vulnerable to shifts in public opinion. In Sweden, efforts to implement less harsh sentencing faced significant backlash following increase in gang-related violence, including 55 fatal shootings in 2023. These incidents pushed the government to strengthen sentencing laws and expand law enforcement powers, showing how sudden increases in crime can shift policy back toward punitive measures [65].

It is essential to support those who have been incarcerated such that they have an optimal entry into their community, and that there is a decrease in recidivism, which also is a focus of the NJRC.

The U.S. Context: A system in crisis

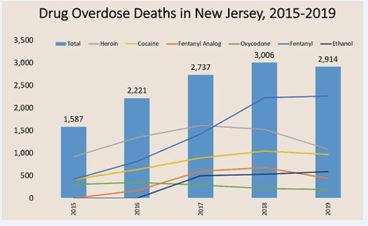

The American system faces unique and deeply entrenched challenges. With just 5% of the world’s population, the U.S. holds nearly a quarter of its prison population. Harsh sentencing laws, the war on drugs, and systemic racism have all played a role [6]. Too often, incarceration is tied to poverty, with people remaining incarcerated simply because they cannot afford bail [8] (Figure 5).

Figure 5 U.S. State and Federal Prison Population, 1925-2022 [7].

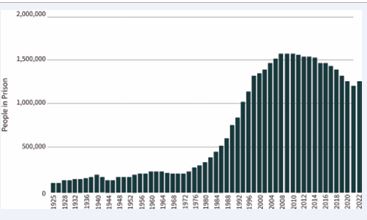

Once inside, incarcerated people lack support systems. Prisons are crowded, underfunded, and often focus more on control than correction [8]. Education and treatment programs are limited [8]. 7 out of 10 people end up back behind bars within three years (11) [68]. There are various reasons why so many individuals are incarcerated in the U.S. prison system including the inability to afford legal counsel, a wide array of state and federal laws, mandatory minimum sentences, and the impact of ethnic and social profiling [8-6]. One major factor is drug-related criminal activity. According to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons, 43.4% of prisoners in the U.S. are incarcerated for drug related offenses [66] (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Incarceration based on offences in USA [66].

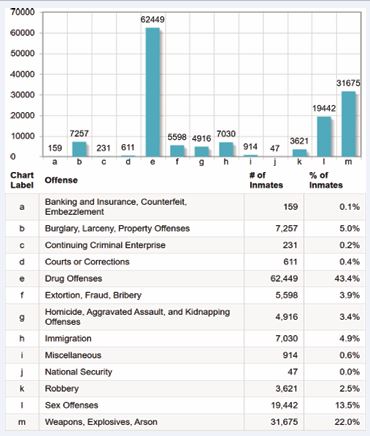

Inmates with drug-related offenses face unique challenges while incarcerated, during court proceedings, and upon reentry [69]. For example, in New Jersey, 65% of inmates have an active substance use disorder (SUD) [58,59]. They require specific treatment that follows medical guidelines for adherence and tapering (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Incidence and cause of drug related deaths in state of New Jersey 2015 2019[58].

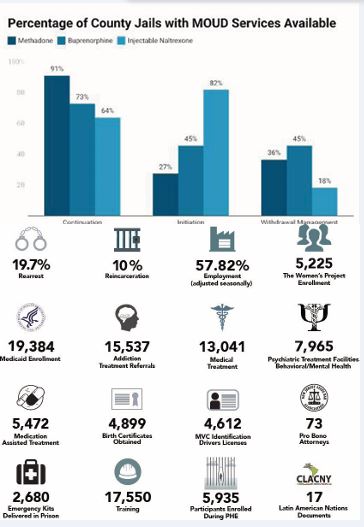

While Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) is available in state prisons, the New Jersey Department of Corrections’ current policies particularly the “taper to-abstinence” approach are not evidence-based [57]. It is recommended that MAT be provided without unnecessary tapering, as continuous treatment has been proven to reduce relapse rates and improve outcomes [11]. While some county jails offer MAT services, access is still inconsistent [11]. It is recommended that the same treatment be implemented uniformly across all facilities, regardless of gender, crime, or sentence duration, following established medical guidelines [58].

Another significant challenge faced by individuals in the U.S. is the lack of support upon reentry. They face barriers to securing housing, obtaining employment, and accessing basic services [70].

However, change is possible, as noted by the NJRC [57]. As of September 30th, 2024, NJRC has served 25,691 program participants, including 1043 veterans, and has secured jobs for 11,808 individuals [59]. NJRC has had an adjusted seasonal employment/training rate of 57.82%. 19,384 individuals have been enrolled in Medicaid. 15,537 participants have received addiction treatment, 13,041 have received medical treatment, and 7965 have received behavioral or mental health services through psychiatric treatment facilities. Additionally, 5472 individuals have accessed medication-assisted treatment, 4899 obtained birth certificates, and 4612 acquired MVC identification or driver’s licenses [59] (Figure 8).

Figure 8 NJ Reentry Corporation program data 2025[59].

hese impressive outcomes from NJRC demonstrate how comprehensive reentry programs can substantially improve the prospects for formerly incarcerated individuals and reduce recidivism. This aligns with international evidence showing that shorter sentences, better reentry support, mental health care, and a focus on rehabilitation can be effective, and investing in supporting individuals both during and after incarceration can break the cycle of mass incarceration. Policymakers must act by scaling evidence-based programs, ensuring equitable access to treatment, and prioritizing reentry support as essential components of criminal justice reform [20-66].

CONCLUSION

Incarceration should not be a mere tool to imprison someone from society but rather a guiding path toward reintegration, a framework where people are given the support and opportunities to grow, reflect, and ultimately return to their communities ready to contribute in meaningful ways. Systems that focus on rehabilitation, dignity, and second chances, such as the NJRC program, do not just help individuals, they strengthen societies.

Every country has its own challenges, histories, and values. But one aspect is universal: real progress does not come from harsher sentences or overcrowded cells; it comes from investing in people by offering education, mental health support, and pathways to reintegration. Justice reform is not about being lenient, it is about being effective, humane, and wise about the kind of society we want to live in.

Clearly, a justice system is not measured by how many people it punishes, but rather by how many it helps to heal and rebuild. For safer communities, then incarceration systems must reflect that belief in redemption, not just retribution.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study because this study involved the analysis of publicly available data.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

REFERENCES

- Schmalleger F, Atkin-Plunk C. Oxford Bibliographies. 2015.

- Tonry M. Punishment and Politics: Evidence and Emulation in the Making of English Crime Control Policy. Crime and Justice. 2013; 42: 217-270.

- Pratt J. Scandinavian Exceptionalism in an Era of Penal Excess. British J Criminol. 2008; 48: 119-137.

- Shinoda J. An Analysis of Penal Policy and Prison Conditions in Japan. University of South Florida Digital Commons. 2018.

- Silva J. Corrections in Japan. Research Gate. 2017.

- Nellis A. The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. The Sentencing Project; 2016.

- The Sentencing Project. Mass Incarceration Trends. 2024.

- Prison Policy Initiative. The Whole Pie 2024: Mass Incarceration in the United States. Prison Policy Initiative. 2024

- Beckett K, Goldberg AE. The Effects of Imprisonment. [Internet]. University of Washington; 2025.

- Penal Reform International. Humanity in Prison: Handbook on Good Prison Practice. 2013.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Handbook on Prisonerswith Special Needs. 2009.

- Subramanian R. How Some European Prisons Are Based on Dignity Instead of Dehumanization. Brennan Center for Justice. November 29, 2021.

- Prison Policy Initiative. Out of Prison & Out of Work: Unemployment among formerly incarcerated people. 2018.

- First Step Alliance. Rehabilitation Lessons from Norway’s Prison System. 2021.

- Wilson RJ, Picheca JE, Prinzo M. Circles of Support & Accountability: A canadian national replication of outcome findings. Sex Abuse. 2007; 19: 411-425.

- Australian Institute of Criminology. Study in Prison Reduces Recidivism and Welfare Dependence. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice. 2010; 514: 1-10.

- Thom K. Exploring Te Whare Whakapiki Wairua/The Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court Pilot: Theory, Practice and Known Outcomes. New Zealand Criminal Law Review. 2017; 25: 152-313.

- Council on Criminal Justice. Reducing Recidivism: How These 5Nonprofits Are Changing Lives. 2025.

- La Vigne N. Transforming Correctional Culture and Climate. National Institute of Justice. 2024.

- The Sentencing Project. Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2024.

- The Sentencing Project. Still Life: America’s Increasing Use of Life and Long-Term Sentences. 2021.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Performance measures for the criminal justice system. U.S. Department of Justice; 2002.

- First Step Alliance. What we can learn from norway’s prison system: Rehabilitation & Recidivism. 2022.

- Bhuller M, Dahl GB, Løken KV. Policies to Reintegrate Former Inmates into the Labor Force. University of California, San Diego; 2017.

- Dahl GB, Mogstad M. The Benefits of Rehabilitative Incarceration.NBER Reporter. 2020.

- Pervana S. Will Norway’s Prison System Work in the U.S.? Revisions& Reflections. 2019.

- Laroia S. Rehabilitative Justice: What the US Can Learn from the Norwegian Model. J Interdisciplinary Public Policy. 2021.

- Gentleman A. Inside Halden, the most humane prison in the world. The Guardian. 2012.

- Toedtman ST. Exploring the Exceptional Corrections Paradigm: An analytical case-study of the norwegian model of criminal justice. Master’s Thesis. University of Tromsø; 2024.

- Gray A. This Norwegian prison is the nicest in the world. World Economic Forum. 2017.

- Burge S. 14 Best Prisons in the World to Serve Time. International Security J. 2024.

- Subramanian R, Shames A. Sentencing and Prison Practices in Germany and the Netherlands: Implications for the United States. Vera Institute of Justice; 2013.

- Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. Criminaliteit en rechtshandhaving 2017: Ontwikkelingen en samenhangen. WODC; 2018.

- Dumortier E, Vervaet M. Learning from Holland: the TBS system. Int J Law Psychiatr. 2007; 30: 319-330.

- Office of Justice Programs. Criminal Justice System – Netherlands.National Criminal Justice Reference Service. 1980.

- Canada Correctional Service. Criminal Justice System – Netherlands. National Criminal Justice Reference Service. 1980.

- US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. Criminal JusticeSystem – Netherlands. 1980.

- Brand-Koolen MJM, editor. Studies on the Dutch Prison System. Ministry of Justice; 2014.

- Boone M, van der Kooij M, Rap S. Current Uses of Electronic Monitoring in the Netherlands. Utrecht University. 2016.

- World Prison Brief. Netherlands. 1970.

- Boone M, Pakes F, van Wingerden S. Explaining the collapse of the prison population in the Netherlands. University of Portsmouth. 2019.

- Van der Zee R. In the Netherlands, we’re closing our emptying prisons. What can other countries learn from how we did it? The Guardian. 2024.

- Sullivan J. An analysis of the Japanese Criminal Justice System. Denver J Int Law Policy. 2003; 31: 1-25.

- Saracho C. How Japan Uses Low Crime Rates To Justify Its Cruel Prison System. Worldcrunch. 2024.

- U.S. Embassy & Consulates in Japan. Information for U.S. Citizens Arrested in Japan. 2022.

- Sawanobori B. Human Rights in Japanese Prisons: Reconsidering Segregation as a Disciplinary Measure. Law & Social Inquiry. 2024.

- Human Rights Watch. Prison Conditions in Japan. Human Rights Watch. 1995.

- Metzner JL, Fellner J. Solitary confinement and mental illness in U.S. prisons: A challenge for medical ethics. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2010; 38: 104-108.

- Amnesty International. Japan: Abusive Punishments in Japanese Prisons. Amnesty International. 1998.

- The Global Economy.com. Japan: Imprisonment rate. 2017.

- EuroPris. Feature Article: A New Approach for Open Prisons in Spain (2023). 2023.

- Blay E. Rehabilitation in Spain: Between Legal Intentions and Institutional Limitations. In: Robinson G, McNeill F, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Rehabilitation in Criminal Justice. Springer; 2022: 541-558.

- Aranda Ocaña M. Alternatives to Prison in Europe: Spain. European Prison Observatory; 2015.

- Martí M. Prisoners in the community: the open prison model in Catalonia. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Kriminalvidenskab. 2019; 2: 211-231.

- Martí J, Larrauri E. Probation in Europe: Spain. Confederation of European Probation; 2018.

- Insider NJ. The New Jersey Reentry Corporation Joins Google Program to Offer Digital Skills Training for People Impacted by Incarceration. 2024.

- New Jersey Reentry Corporation. Annual Report 2024. 2024.

- New Jersey Reentry Corporation. NJRC Program Data Infographic 2025. 2025.

- CalMatters. California prisons: Why state spending tops $132,000 per inmate. 2024.

- Apolitical. In Brazil, an experimental prison gives inmates the keys to their cells. 2018.

- Prison Reform Trust. What if there was no Criminal Justice Act 2003? 2017.

- Zimring FE, Hawkins G, Kamin S. Punishment and Democracy: Three Strikes and You’re Out in California. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Feeley MM. Opening Keynote Address: How to Think About Criminal Court Reform. Boston University Law Rev. 2018; 98: 673-730.

- Feeley MM. Opening Keynote Address: How to Think About Criminal Court Reform. Boston University Law Review. 2018; 98: 673-730.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons. Inmate Offenses. 2025.

- Nellis A. The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. The Sentencing Project; 2016.

- Durose MR, Cooper AD, Snyder HN. Recidivism of prisoners released in 30 States in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2014.

- Marlowe DB. Drug Courts: The Good, the Bad, and the Misunderstood. In: Jeglic EL, Calkins C, eds. Handbook of Issues in Criminal Justice Reform in the United States. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022: 637-656.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the assistant secretary for planning and evaluation. Reentry and Housing Stability: Final Report. 2024.