Correlation between Human Oocytes with Waxy or Indented Zona Pellucida and Environmental Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

- 1. Beijing Perfect Famliy Hospital, China

Abstract

Environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals (EEDCs) are widely present in people’s daily living environments. EEDCs can mimic endogenous hormones or competitively bind to their receptors, thereby exerting a series of biological functions and posing a serious threat to human reproductive health. Seeking the relationship between EEDCs and the abnormal zona pellucida (ZP) of the human oocyte and clinic treatment outcomes is of significant importance for shortening the time for women to prepare for pregnancy and maintaining human reproductive health. 19 cases of patients (case group) with oocytes exhibiting a waxy or indented ZP were retrospectively analyzed in our reproductive center. We found that patients in case group have significantly increased infertility duration and transfer cancellation rate, significantly reduced AMH level, E2 level on hCG day, average number of retrieved oocytes, oocyte maturation rate, fertilization rate and normal fertilization rate. Oocytes with waxy or indented ZP often experience all fertilization failure or low fertilization rates after conventional IVF fertilization, the fertilization problem can be resolved by ICSI fertilizaiton. There were no significant differences compared to the control group in clinical pregnancy rate (34.62% vs 47.06%), miscarriage rate (0 vs 4.71%) and live birth rate (34.62% vs 42.35%). 15 out of 19 patients had occupational exposure, such as the clothing/shoe sales or fabric dyeing industry, the makeup industry, the decoration industry, and the catering industry. Patients with oocytes exhibiting a waxy or indented ZP usually have a history of occupational exposure or long-term adverse environmental contact.

Keywords

• Environmental Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EEDCs)

• Oocyte

• Waxy or Indented Zona Pellucida

• Embryo

• Human

Citation

Zuo X, Luo Y, Du S, Xu H, Chen C, et al. (2025) Correlation between Human Oocytes with Waxy or Indented Zona Pellucida and Environmental Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals. JSM Sexual Med 9(4): 1164.

INTRODUCTION

The zona pellucida (ZP) is a three-dimensional mesh matrix that surrounds the mammalian oocyte [1]. The ZP is secreted and synthesized by the primary oocyte and its surrounding granulosa cells. It plays a crucial role in mediating sperm binding, inducing the acrosomal reaction, preventing polyspermy and protecting the embryo until implantation [2]. The human oocyte ZP consists of four glycoproteins: ZP1, ZP2, ZP3, and ZP4 [3]. These proteins are synthesised in the endoplasmic reticulum, and then transferred to the Golgi and delivered to the oocyte membrane by exocytosis [4]. The ZP1 protein is a major structural component of the ZP. Homozygous mutations in ZP1 can lead to oocytes lacking ZP, and such oocytes can still achieve healthy offspring through ICSI fertilization method [5]. The ZP2 protein is essential for sperm binding and penetration through the ZP [6]. Homozygous mutations in ZP2 result in thin and structurally disordered ZP in patients’ oocytes, leading to fertilization failure during routine IVF, with the blockage occurring at the sperm-ZP binding stage. However, ICSI can achieve normal fertilization and healthy live births [7]. Heterozygous missense mutations in ZP3 can cause recurrent failure to aspirate oocytes, as these mutations damage the assembly of ZP proteins, leading to oocyte degeneration [8].

Human oocyte morphological abnormalities include intracytoplasmic abnormalities, such as vacuoles, refractile bodies, darkened oocytes, central granulation of the oocyte, and aggregates of smooth endoplasmic reticulum clusters, and extracytoplasmic abnormalities including ZP abnormalities, enlarged or absent perivitelline space (PVS), abnormal first polar body (PB), irregularly shape, gaint oocyte and so on [9,10]. It is known that oocytes with waxy or indented ZP have no resistance when performing ICSI operations, with reduced cytoplasmic viscosity, and lower rates of oocyte retrieval and MII [11]. Patients with waxy or indented ZP cannot be clinically detected in advance. These oocyte ZPs have sparse cumulus cells surrounding them, and the connection between the ZP and the cumulus cells is not very tight, making them easy to detect during egg retrieval. During denudation, it is easy to remove the peripheral cumulus cells from the oocyte, and under an inverted microscope, ZP morphological abnormalities are easily observed [12]. Oocytes with waxy or indented ZP often experience all fertilization failure or low fertilization rates after conventional IVF, making it difficult for patients to obtain transferable embryos. However, ICSI can improve the fertilization rate of these oocytes, avoiding fertilization failure or low fertilization, thus achieving good pregnancy outcomes [13]. Clinically, factors such as patient BMI, reproductive endocrine hormone levels, age, and ovulation induction protocols have no direct correlation with waxy or indented ZP, because even with different ovulation induction protocols, patients can still experience waxy or indented ZP [12]. Patients with waxy or indented ZP typically do not have ZP-related gene mutations [14].

With the increase in global industrial activities, humans are exposed to a variety of chemical pollutants, collectively known as EEDCs [15]. Studies have shown that EEDCs can mimic endogenous hormones or competitively bind to their receptors, thereby exerting a range of biological functions. Due to their widespread exposure and endocrine-disrupting properties, they can adversely affect reproductive health [16]. However, there have been no reports on the impact of EEDCs on the human oocyte ZP to date. Exploring the connection between EEDCs and abnormalities in the human oocyte ZP and taking corresponding intervention measures are of significant importance for shortening the time for women to prepare for pregnancy and for reproductive health education work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Data Collection

From January 2013 to December 2023, a retrospective analysis was conducted on 19 patients who underwent IVF/ ICSI treatment at our reproductive center and presented with oocyte ZP appearing waxy or indented, along with their clinical treatment outcomes. By inquiring, reviewing medical records and conducting telephone follow-ups with patients to assess their occupational exposure and daily living environments, we sought to identify correlations between EEDCs and ZP abnormalities. The control group comprised 60 patients with normal ZP morphology at our reproductive center between 2018 and 2023. Ten cases were randomly selected annually, excluding patients who met any of the following criteria: age over 40 years, poor ovarian response, oocyte donation, thawed oocytes, chromosomal abnormalities, sperm donation, or sperm retrieval by surgical epididymal and testicular techniques.

Assessment of Ovarian Function

Ovarian reserve function was comprehensively assessed based on the patient’s age, ovarian volume, antral follicle count and basic endocrine level. Venous blood was extracted and serum hormones, including follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), oestradiol (E2), progesterone (P), luteinizing hormone (LH), and human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), were analysed in the morning of the second or third day of the menstrual cycle.

Ovulation Stimulation Control and Oocyte Retrieval

Personalized ovulation induction protocols were selected, including the long protocol, short protocol, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist protocol. When a type B ultrasonic instrument showed a follicular diameter of 18 mm in three oocytes, hCG (5,000–10,000 IU) was administered. Oocyte retrieval was performed by transvaginal ultrasound-guided puncture 36 h later.

Insemination and Embryo Culture

Under a stereomicroscope, the cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCS) in follicular fluid were identified and then collected. The COCS were washed with a series of culture media and then incubated in a 37?, 5%O2 and 6%CO2 incubator for 4-6 h and then underwent ICSI or IVF insemination based on each patient’s sperm quality. Semen samples were collected after a recommended abstinence period of 2-7 days via masturbation into a sterile container. Semen was processed using density gradient centrifugation or the swim-up technique. Fertilization was achieved through either IVF or ICSI. For IVF, oocytes were co-incubated with sperm at a concentration of 1×10?sperm/mL in a four-well dish at 4–6 hours post retrieval. Fertilization was assessed 6 hours later, with rescue ICSI performed on unfertilized oocytes. For ICSI, oocytes underwent denudation of cumulus cells using 80 IU hyaluronidase prior to microinjection. Fertilization success was confirmed by the presence of two pronuclear (2PN) and 2PBs 16–18 hours post-insemination. Embryos were cultured individually in 30 μL microdroplets G1.5 (Vitrolife, Sweden) in a 37.0?, 5%O2 , 6%CO2 COOK incubator. Embryo development was monitored and recorded on Day 3 and then transferred them to G2.5 culture medium for blastocyst culture. Blastocyst was evaluated on Day 5–6.

Embryo Transfer and Pregnancy Diagnosis

Embryo transfer was performed on the third or fifth day after oocyte retrieval for fresh embryo and on the third- or fifth-day endometrial transformation for thawing embryo. Optimal embryos (1–2) were selected for transfer based on morphological criteria. Biochemical pregnancy was defined as a serum β-hCG level ≥50 mIU/mL at 14 days after embryo transfer. Clinical pregnancy was confirmed by the visualization of a gestational sac by transvaginal ultrasound at 5 weeks of gestation.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical treatment was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 and MATLAB R2023b. Descriptive statistics were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous measures and percentages for enumeration data. For the measurement data, the t-test was adopted, while the chi-square test was used to enumeration data. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p-value was <0.05.

RESULTS

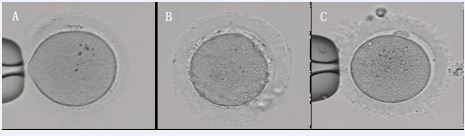

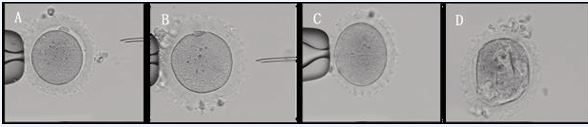

We retrospectively analyzed 19 cases of patients undergoing IVF/ICSI treatment at our center from January 2013 to December 2023, which the ZP of the oocytes appeared waxy (Figure 1A and B) or indented (Figure 1C) morphological changes, with a bright color. Some oocytes have a small or absent perivitelline space, and the first PB is small or flat (Figure 2A and 2B) or difficult to detect (Figure 2C and 2D).

Figure 1 Normal ZP and waxy or indented ZP. A. Normal ZP. B. Waxy ZP. C. Indented ZP. 200×

Figure 2 Waxy or indented ZP oocytes with varying degrees of alteration. A. Both PVS and PB are normal. B. Absent PVS, with small and flat PB. C. Absent PVS and PB. D. With multiple and big vacuolus. 200×

We found that the basic clinical characteristics of the case group, such as age, basal endocrine levels, ovarian reserve function,and the days and total Gn doses of ovarian stimulation, were not different from those of the control group (Table 1).

Table 1: Basic clinical information of patients.

|

Parameter |

Case Group |

Control Group |

P-value |

|

Total OPU cycles (n) |

32 |

60 |

- |

|

No. of patients (n) |

19 |

60 |

- |

|

Age (year, mean±sd) |

33.53±5.10 |

33.22±3.45 |

0.807 |

|

Duration of infertility (year, mean±sd) |

7.26±3.16 |

4.80±3.43 |

0.007 |

|

bFSH (IU/L, mean±sd) |

8.50±3.82 |

6.76±2.31 |

0.073 |

|

bLH (IU/L, mean±sd) |

3.74±2.78 |

4.56±2.24 |

0.198 |

|

bE2 (pg/ml, mean±sd) |

47.75±23.92 |

39.41±2.17 |

0.165 |

|

AMH (ng/ml, mean±sd) |

3.02±3.06 |

4.99±3.16 |

0.037 |

|

Days of ovarian stimulation (mean±sd) |

9.53±3.30 |

9.8167±1.48 |

0.645 |

|

Total Gn doses (IU/L, mean±sd) |

2590.63±1418.68 |

2583.56±783.24 |

0.975 |

|

E2 on HCG day (pg/ml, mean±sd) |

2425.12±1801.65 |

3436.92±1752.00 |

0.011 |

However, patients in case group have significantly increased infertility duration (7.26 vs 4.80) (p<0.01), significantly reduced the AMH level (3.02 vs 4.99) (p<0.05), significantly decreased the E2 level on hCG day (2425 vs 3436) (p<0.05), the average number of retrieved oocytes (8.56 vs 13.60) (p<0.01), the maturation rate of oocytes (63.64 vs 79.13) (p<0.01), the fertilization rate (58.39 vs 74.63) and normal fertilization rate (51.46 vs 61.89) (p<0.01), significantly increased transfer cancellation rate (25.0 vs 0) (p<0.01). In case group, 18 patients had primary infertility, and only one had secondary infertility, which lasted for 8 years. 11 patients (57.89%) had normal male semen, and 10 underwent IVF fertilization in their first cycle, 9 experienced complete fertilization failure or low fertilization rates, but normal fertilization was achieved after rescue-ICSI. Under an inverted microscope, it can be observed that sperm can bind to the ZP but cannot penetrate it to complete fertilization, which also explains the reason for the fertilization failure of conventional IVF of oocytes with waxy or indented ZP. 8 cycles of 6 patients had no transferable embryos due to nonfertilization, or abnormal fertilization, or obvious cytoplasmic abnormalities such as multiple vacuoles in the oocytes (Figure 2D). 16 patients who had transferable embryos underwent 26 embryo transfer cycles, with a clinical pregnancy rate of 34.62% (9/26), no miscarriages, and a live birth rate of 34.62% (9/26). 14 babies (7 males and 7 females) were born without any congenital malformations. There were no significant differences compared to the control group in a clinical pregnancy rate (47.06%), miscarriage rate (4.71%) and live birth rate (42.35%) (Table 2).

Table 2: The results of early development in the patients’ oocytes and clinical outcomes.

|

Parameter |

Case Group |

Control Group |

P-value |

|

Retrieved oocyte number (mean ± sd) |

8.56±6.32 |

13.60±5.89 |

0.000 |

|

Oocyte mature rate (%) |

63.64 119/187 |

79.13 292/369 |

0.000 |

|

Fertilization rate* (%) |

58.39 160/274 |

74.63 609/816 |

0.000 |

|

Normal fertilization (2PN) rate (%) |

51.46 141/274 |

61.89 505/816 |

0.002 |

|

Cleavage rate (%) |

95.63 153/160 |

97.54 594/609 |

0.306 |

|

D3 available embryo rate (%) |

79.87 123/154 |

84.51 502/594 |

0.166 |

|

D3 high-quality embryo rate (%) |

34.29 48/140 |

38.51 191/496 |

0.362 |

|

Blastocyst formation rate (%) |

62.32 43/69 |

64.93 224/345 |

0.679 |

|

Available blastocyst formation rate (%) |

76.74 33/43 |

79.02 177/224 |

0.739 |

|

Transfer cancellation rate (%) |

25.00 8/32 |

0 0/60 |

0.000 |

|

Clinical pregnancy rate (%) |

34.62 9/26 |

47.06 40/85 |

0.263 |

|

0 0/26 |

4.71 4/85 |

0.571 |

|

Live birth rate (%) |

34.62 (9/26) |

42.35 (36/85) |

0.226 |

*Fertilization rate (denominator is the number of oocytes retrieved).

Our results indicated that patients with waxy or indented ZP oocytes had significantly lower AMH levels, the average number of retrieved oocytes, the oocyte maturation rate, and the fertilization rate. However, if they had good underlying conditions and no other morphological abnormalities of the oocytes (such as multiple vacuoles in the oocytes, severe central granulation, etc.) or factors that directly affect pregnancy outcomes (such as advanced age), satisfactory pregnancy outcomes were achieved after ICSI fertilization.

To further explore the specific reasons for the waxy or indented changes in the ZP of oocytes, we inquired about the patients’ occupational history, their daily and work environments, and the duration of environmental exposure. We found that most women had a history of exposure to EEDCs. Follow-up revealed that among these 19 patients, 6 were involved in the sale or production of clothing and shoes, 2 in the textile dyeing industry, 2 in the cosmetics industry, 2 in the decoration industry, 3 in the catering industry, and 4 were unemployed. In the clothing, shoe sales, and textile dyeing industries, patients were frequently exposed to xylene, toluene, and other EEDCs. Patients in the cosmetics industry were likely mainly exposed to phthalates, parabens, triclosan, and VOCs. The decoration industry might be exposed to more formaldehyde, methane, and VOCs, etc. Patients in the catering industry were mainly affected by cooking fumes, which typically contain acrolein (Table 3).

Table 3: Major types of EEDCs related to reproduction, their half-lives, and main exposure environments.

|

EEDCs |

Half-lives |

Primary exposure environment |

|

Bisphenol A (BPA) |

≈ 6 hours |

Food contamination, such as from plastic bags, water bottles and baby bottles, aging of bottles and packaging, food and beverage cans, and microwave ceramics. |

|

VOCs (xylene, toluene, formaldehyde, ethylene, methanol, etc.) |

From several hours to 2 days |

Building materials, interior decoration materials, outdoor industrial gases, fabric dyeing, such as industrial waste gas, vehicle exhaust, paint, tobacco, and cooking fumes, etc. |

|

Phthalates |

≈3-18 hours |

Primarily used for packaging materials, such as food packaging, children's toys, personal care products, cosmetics, etc. |

|

Triclosan (TCS) |

≈10-14 |

Personal care products, industrial and household products, such as disinfectants, soaps, toothpaste, toys, medicines, and medical devices, etc. |

|

Parabens |

About 1-2 days |

Preservatives, widely used in cosmetics, personal care products, pharmaceuticals, and food. |

|

Organochlorine pollutants (OPs) |

Several years |

Pesticides, flame retardants, and various cleaning products, etc. |

|

Perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) |

Several years |

Artificial items, such as cleaning products, food containers, and pesticides, etc. |

|

Acrolein |

From several hours to 2 days |

Cooking fumes, rubber, plastics, spices, synthetic resins, vehicle exhaust, cigarette smoke, construction and decorative materials, etc. |

This suggests that EEDCs may change the intrafollicular environment of the female ovary, affecting ovarian function and the normal assembly of ZP-related proteins in oocytes, thereby presenting morphological changes in the ZP.

DISCUSSION

The interaction between oocytes and surrounding granulosa cells in follicles, as well as hormones and growth factors, is crucial for the development and maturation of oocytes [17]. The oocyte in primordial follicles does not have ZP, which first appears in primary follicles and is a glycoprotein secreted jointly by the primary oocyte and surrounding granular cells [3]. The protein fibers of the waxy or indented ZP are disordered, loosely structured, uniform without stratification, and lack microvilli, [13] indicating that there is an abnormality in the synthesis and assembly of ZP proteins. Some study [12] have found that 65.51% (38/58) of patients with waxy or indented ZP have pelvic inflammatory disease, and they hypothesize that the waxy or indented changes in ZP may be caused by inflammatory factors. Among the 19 patients with waxy or indented ZP at our center, 11 (57.89%) also had a history of pelvic inflammatory disease or salpingitis, but many women with pelvic inflammatory disease or salpingitis did not show changes in ZP morphology, suggesting that inflammation is not the direct cause of the waxy or indented ZP changes of oocytes.

EEDCs can interfere with the production, secretion, transport, metabolism, binding, and excretion of natural hormones in the body, potentially leading to precocious puberty, ovulation disorders, infertility, and other reproductive-related diseases [18]. EEDCs are extremely diverse, and currently known reproductive-related EEDCs include bisphenol A (BPA), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), triclosan, phthalates, parabens, perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) [19-21]. An increasing number of studies also suggest that exposure to EEDCs is associated with gynecological diseases, including endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), premature ovarian failure (POF), and others [22]. The development process of the oocyte occurs in the follicular fluid, which is composed of products transported from maternal blood through the blood-follicle barrier and products secreted by cumulus cells. The follicle is a very fragile microenvironment, and an increasing number of studies show that EEDCs can enter the female bloodstream through the respiratory system, digestive system, skin contact, hair follicle absorption, and other pathways, thereby altering the internal environment of the ovarian follicle [20,21,23]. Higher concentrations of EEDCs in the follicular microenvironment can reduce the average number of retrieved oocytes, the maturation rate of oocytes and the fertilization rate, indicating that the oocyte is in close contact with EEDCs in the follicular fluid, which may directly or indirectly affect the development process of the follicle or the oocyte, thereby reducing the quality of the oocyte [23,24].

How exactly does the change in the follicular environment affect the normal synthesis and assembly of ZP? We hypothesize that patients who have been exposed to EEDCs in daily life and work environments for a long time and in high doses, EEDCs may enter the bloodstream through skin contact, the respiratory system and diet affecting the microenvironment of ovarian primordial follicles, interfere with several signal pathways closely related to it, change the transcription and post translational modification processing of related proteins, and ultimately these changes affect the synthesis and assembly of ZP proteins. However, due to the wide variety of EEDCs, there may be a combined effect of several EEDCs, different lengths of time patients have been exposed to these EEDCs, different pathways of entry into the body, different concentrations of EEDCs entering the body, and the individual physical condition, health status, and lifestyle of female patients are also different, affected by these complex variables, it is difficult for researchers to control a single variable on humans and obtain convincing evidence. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the sample size or conduct multi-center studies, combine epidemiological investigations, establish detailed patient profiles with waxy or indented ZP, focus on several types of EEDCs, and further clarify the mechanism of action of EEDCs on oocytes through animal models. At the same time, it is necessary to increase the publicity of assisted reproductive science, improve the awareness and literacy of reproductive health among the reproductive-age population nationwide, maintain a healthy lifestyle, and stay as far away from EEDCs as possible, truly achieving preventive treatment and preventing problems before they occur.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to our colleagues at the Reproductive Center for their invaluable advice and support throughout the course of this scientific study.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The present study was initiated and conducted after the Committee of Ethics approval from Beijing Perfect Family Hospital (Beijing, China; Approval No. 2020-12-23).

REFERENCES

- Wassarman PM, Mortillo S. Structure of the mouse egg extracellular coat, the zona pellucida. Int Rev Cytol. 1991; 130: 85-110.

- Gupta SK, Bhandari B, Shrestha A, Biswal BK, Palaniappan C, Malhotra SS, et al. Mammalian zona pellucida glycoproteins: structure and function during fertilization. Cell Tissue Res. 2012; 349: 665-678.

- Stetson I, Avilés M, Moros C, García-Vázquez FA, Gimeno L, Torrecillas A, et al. Four glycoproteins are expressed in the cat zona pellucida. Theriogenology. 2015; 83: 1162-1173.

- Green DP. Three-dimensional structure of the zona pellucida. Rev Reprod. 1997; 2: 147-156.

- Huang HL, Lv C, Zhao YC, Li W, He XM, Li P, et al. Mutant ZP1 in familialinfertility. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370: 1220-1226.

- Maegawa M, Kamada M, Yamamoto S, Yamano S, Irahara M, Kido H, et al. Involvement of carbohydrate molecules on zona pellucida in human fertilization. J Reprod Immunol. 2002; 53: 79-89.

- Dai C, Hu L, Gong F, Tan Y, Cai S, Zhang S, et al. ZP2 pathogenic variants cause in vitro fertilization failure and female infertility. Genet Med. 2019; 21: 431-440.

- Chen T, Bian Y, Liu X, Zhao S, Wu K, Yan L, et al. A Recurrent Missense Mutation in ZP3 Causes Empty Follicle Syndrome and Female Infertility. Am J Hum Genet. 2017; 101: 459-465.

- Nikiforov D, Grøndahl ML, Hreinsson J, Andersen CY. Human Oocyte Morphology and Outcomes of Infertility Treatment: a Systematic Review. Reprod Sci. 2022; 29: 2768-2785.

- Yu EJ, Ahn H, Lee JM, Jee BC, Kim SH. Fertilization and embryo quality of mature oocytes with specific morphological abnormalities. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2015; 42: 156-162.

- Sousa M, Teixeira da Silva J, Silva J, Cunha M, Viana P, Oliveira E, et al. Embryological, clinical and ultrastructural study of human oocytes presenting indented zona pellucida. Zygote. 2015; 23: 145-157.

- Yang D, Yang H, Yang B, Wang K, Zhu Q, Wang J, et al. Embryological Characteristics of Human Oocytes With Agar-Like Zona Pellucida and Its Clinical Treatment Strategy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022; 13: 859361.

- Shi SL, Yao GD, Jin HX, Song WY, Zhang FL, Yang HY, et al. Correlation between morphological abnormalities in the human oocyte zona pellucida , fertilization failure and embryonic development. 2016.

- Margalit M, Paz G, Yavetz H, Yogev L, Amit A, Hevlin-Schwartz T, et al.Genetic and physiological study of morphologically abnormal human zona pellucida. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012; 165: 70-76.

- Younglai EV, Holloway AC, Foster WG. Environmental and occupational factors affecting fertility and IVF success. Hum Reprod Update. 2005; 11: 43-57.

- Ma Y, He X, Qi K, Wang T, Qi Y, Cui L, et al. Effects of environmental contaminants on fertility and reproductive health. J Environ Sci (China). 2019; 77: 210-217.

- Martinez CA, Rizos D, Rodriguez-Martinez H, Funahashi H. Oocyte- cumulus cells crosstalk: New comparative insights. Theriogenology. 2023; 205: 87-93.

- Patel S, Zhou C, Rattan S, Flaws JA. Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals on the Ovary. Biol Reprod. 2015; 93: 20.

- Agarwal N, Chattopadhyay R, Ghosh S, Bhoumik A, Goswami SK, Chakravarty B. Volatile organic compounds and good laboratory practices in the in vitro fertilization laboratory: the important parameters for successful outcome in extended culture. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017; 34: 999-1006.

- Dann AB, Hontela A. Triclosan: environmental exposure, toxicity and mechanisms of action. J Appl Toxicol. 2011; 31: 285-311.

- Machtinger R, Orvieto R. Bisphenol A, oocyte maturation, implantation, and IVF outcome: review of animal and human data. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014; 29: 404-410.

- Kim YR, Pacella RE, Harden FA, White N, Toms LL. A systematic review: Impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals exposure on fecundity as measured by time to pregnancy. Environ Res. 2019; 171: 119-133.

- Karwacka A, Zamkowska D, Radwan M, Jurewicz J. Exposure to modern, widespread environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals and their effect on the reproductive potential of women: an overview of current epidemiological evidence. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2019; 22: 2-25.

- Petro EM, Leroy JL, Covaci A, Fransen E, De Neubourg D, Dirtu AC, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in human follicular fluid impair in vitro oocyte developmental competence. Hum Reprod. 2012; 27: 1025-1033.