Determinants of Sperm Quality: Impacts of Environment, Lifestyle, Nanoparticles, and the Therapeutic Role of Medicinal Plants

- 1. Department of Zoology, University of Rajasthan, India

Abstract

Male infertility is a growing global health concern, with declining sperm quality emerging as a major contributing factor. Sperm function and integrity are highly sensitive to a range of intrinsic and extrinsic influences. Environmental exposures such as heat, radiation, heavy metals, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals can impair spermatogenesis and sperm function. Lifestyle-related factors, including poor diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, and psychological stress, further exacerbate sperm damage through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, hormonal imbalance, and DNA fragmentation. Additionally, the increasing biomedical and industrial use of nanoparticles has raised concerns regarding their potential reproductive toxicity, as they can cross biological barriers and disrupt testicular physiology. In contrast, medicinal plants and their bioactive phytochemicals have shown promising protective effects in restoring sperm quality by mitigating oxidative stress, enhancing antioxidant defence, regulating hormonal activity, and improving spermatogenesis. This review synthesizes current evidence on how environmental and lifestyle factors, as well as nanoparticle exposure, compromise male reproductive health, while also highlighting the therapeutic potential of medicinal plants in preserving and enhancing sperm quality.

Keywords

Environmental exposure; Radiation; Nanoparticles; Spermatogenesis; Medicinal plants.

Citation

Mali PC, Yadav P, Bharti N, Kumari S, Saini M, et al. (2025) Determinants of Sperm Quality: Impacts of Environment, Lifestyle, Nanoparticles, and the Therapeutic Role of Medicinal Plants. JSM Sexual Med 9(5): 1172.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, 8–12% of couples experience infertility, with male causes accounting for 50% of instances. Additionally, an estimated 7% of males worldwide suffer from male infertility [1]. Semen quality evaluation is performed to assess male infertility and identify the factors affecting sperm function. Many analytical approaches have been created since the first works and up to the present. The morphology and physiology of the spermatozoan are studied in great detail by these assays, but they are still not very good at predicting male fertility [2]. Fertility is defined as the rate of reproduction and the capacity to produce new generations; nevertheless, during the past 200 years, it has been dropping internationally. The biological potential of the number of offspring that can be obtained during a lifetime is measured by fecundity, whereas the fertility rate shows how many offspring can be generated during a person’s lifespan [3]. The quality of male semen is essential for both healthy birth and healthy breeding, which are critical steps in raising the standard of reproductive health, population health, and race continuance. There are several indicators that make up the semen quality measure. Andrologists have always faced a difficult task in accurately assessing the quality of semen from initial semen analysis data reports, with reference values for semen indicators set by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4]. These days, males deal with a lot of stress and more exposure to their jobs regularly. Numerous factors, including air pollution, smoking, drinking, being overweight or obese, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), heavy metals, social stress, and some disorders, have been identified as potentially detrimental to the quality of male sperm. Additionally, the 90-day spermatogenesis period allowed for adequate exposure time for these variables [5].

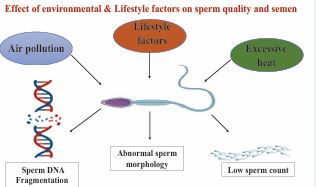

Figure 1 Environmental & Lifestyle factors which affects sperm quality.

The quality of human semen has declined for many years. Numerous studies have shown that this degeneration may be caused by exposure to air pollution or toxins, cell phone electromagnetic waves, obesity, drinking, smoking, psychological stress, hypertension, and diabetes. Given the vast number of impacted communities, outdoor air pollution has recently gained attention. The precise impact of air pollution on semen quality is still unknown [6] We also touch briefly on other issues like sleep deprivation, extreme cycle exercise, testicular heat stress, and electromagnetic radiation exposure from cell phone use. Reduced male fertility is known to be associated with cigarette smoking (Figure 1). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are mostly produced endogenously by leucocytospermia, which is linked to smoking. Furthermore, ROS levels in tobacco smoke are high enough to overpower the body’s natural antioxidant defenses. Smokers elevated seminal ROS levels subject spermatozoa to oxidative stress, which subsequently compromises sperm function and, ultimately, male fertility [7]. Obesity and metabolic syndrome-induced excessive fat deposition in the scrotal region will eventually impair spermatogenesis by causing proinflammatory conditions once adipocytes break down [8]. In addition to tobacco use, alcohol use has been shown to negatively impact the male reproductive system. Previous research has shown that drinking alcohol negatively impacts testicular function, which in turn damages the male reproductive system. According to one study, 42% of infertile males drink alcohol out of the entire population of infertile men. According to this study, one of the main causes of male infertility is alcohol [9]. According to several reports, human sperm are extremely sensitive to nutritional flux, regardless of whether alterations take place in sperm motility or in tiny RNA generated from sperm transfer RNA (tRNA). One element that is directly tied to us and has a significant influence on our lives is our diet. Consuming processed red meat and poultry, as well as artificially sweetened beverages, did not significantly correlate with semen quality markers, according to a study. Therefore, research on how dietary patterns affect semen quality is crucial, as is research on whether the food groups and nutrients found in a balanced diet can have a positive impact on semen quality [10]. Due to the complexity of diet as an exposure variable, the relationship between diet and illness risk must be examined using a variety of methodologies. Conventional analyses in nutritional epidemiology usually look at how a single or a small number of nutrients or foods relate to certain diseases [11]. Additionally, 72 asthenozoospermic patients and 169 normozoospermic controls from Iran were examined for correlations between the consumption of various food categories and the chance of developing various idiopathic asthenozoospermia infertility. Those with asthenozoospermia were found to eat fewer chicken, vegetables (such as oranges, tomatoes, and dark green vegetables), seafood, and skim milk than controls. But a significantly higher risk of rapid henozoospermia was linked to a higher intake of processed meats, dairy items, and sweets [12].

Factors affecting Sperm Quality

The evaluation of male fertility relies on sperm evaluation. Sperm evaluation techniques, such as flow cytometric analysis, computer-assisted sperm analysers (CASA), and traditional microscopy techniques, offer accurate information about the morphology and function of sperm. It is advised to use gene expression testing for quicker and field-level applications. Semen evaluation measures several sperm quality factors as measures of fertility. But semen evaluation has its shortcomings, and it calls for the development and implementation of rigorous quality control methods to interpret the results [1].

The reproductive efficacy of boars is often assessed through the analysis of semen quality. Sperm quality depends on both intrinsic (genetic) factors and extrinsic (environmental) factors. In relation to intrinsic, Crossbred boars often show better fertility as compared with purebred boars due to heterosis, and testis size at pre-pubertal age serves as an important indicator of reproductive potential, whereas abnormalities like cryptorchidism impair spermatogenesis. Environmental stressors such as high temperature, photoperiod, and semen collection frequency negatively affect fertility, while nutritional supplementation, social interaction, and standardized semen handling practices enhance artificial insemination outcomes. Pig breeders place a high value on tracking and evaluating the quality of boar semen because the main factor influencing an artificial insemination (AI) center’s profitability is the boar’s capacity to produce spermatozoa. [13]. The reported studies in human beings indicate that there are good and quite consistent findings that certain pesticides other than DBCP (e.g. DDT/Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene [DDE], ethylenedibromide, organophosphates) impair sperm count. PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) harm sperm motility. Mobile phones may have a negative influence on the semen quality by reducing predominantly motility but also the number of sperm, viability and morphology. The evidence on THMs (Trihalomethanes) is less consistent, with some studies showing adverse effects on semen quality, while others observe no significant association to THMs [14].

According to the review studies, the human X chromosome’s short arm contains the proAKAP4 (Akap4) gene at the Xp11.22 location. The proAKAP4 is a highly conserved molecule across species from reptiles such as lizards and crocodiles through all mammals and shares more than 70% of homology. The AKAP4 is widely recognised as the sperm-specific member of the extensive A-kinase anchor protein family. One important protein that is vital to sperm function is the proAKAP4 precursor. The capacity of ejaculated spermatozoa to fertilise, which is now being assessed by using the 4MID® kits, which measure proAKAP4 expression levels in ejaculate and/ or dosages. In order to inform the prediction of male fertility and prolificity in breeding operations, measuring the expression levels of proAKAP4 should yield relevant data. The 4MID® kits are an excellent illustration of how proteomics and biotechnology works together in veterinary practices [15]. According to a few studies, the rate of infertility among males with diabetes mellitus ranges from 35% to 51%, while the incidence of diabetes mellitus among infertile men varies from 0.7% to 1.4%. Couple fertility is negatively impacted by male diabetes mellitus, while men who are childless or infertile may be more susceptible to the disease. Despite contradictory results on various semen characteristics, two meta analyses support a negative effect of diabetes mellitus on sperm normal morphology and no effect on sperm total count. Based only on research including men with type 1 diabetes, meta-analyses show that the disease has a detrimental impact on sperm motility but has no effect on sperm total count. Other semen parameters show varying results. Males with type 1 diabetes had a lower prevalence of children than controls, especially those who had had the disease for a longer period of time. Pregnancy rates were lower for men undergoing assisted reproduction procedures whose male spouse had diabetes mellitus than for controls [16]. The current research explored the reproductive toxicity of lead acetate in adult male mice through exposure to different concentrations in drinking water for six weeks. Lead accumulation was measured in blood, testis, and epididymis, and histomorphological changes in reproductive tissues were analyzed. Sperm quality was determined by density, viability, motility, and morphology, whereas DNA integrity was tested using TUNEL, alkaline comet assay, and sperm chromatin structure assay. Even though no significant impact on the body weight was noticed, increased lead levels (0.5% and 1%) profoundly decreased the motility of the sperm and raised the number of morphologically deformed spermatozoa. In addition, exposure to lead acetate at 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1% significantly increased the frequency of sperm DNA fragmentation and chromatin damage. These results indicate that exposure to lead negatively impacts both physiological and molecular sperm parameters, potentially impairing male fertility [17].

Effects of nanoparticles on sperm quality

Human exposure to manufactured nanoparticles has increased as a result of the development of nanotechnologies during the past three decades. Numerous regulatory agencies have encouraged research on the effects of nanoparticles on human reproduction, especially male fertility, as a result of the concurrent rise in human exposure to nanoparticles and decline in sperm quality [18]. The testicular distribution and bio persistence of nanoparticles are expected to be contingent on multiple factors, including the employed animal model, the particles’ physicochemical characteristics (size, shape, surface chemistry, tendency to agglomeration), route, duration of exposure and the diluent used at the time of administration [19].

Sperm cells are especially vulnerable to reactive oxygen species (ROS) because they have low levels of enzymatic antioxidants and high levels of ROS and DNA fragmentation, which have been observed in the spermatozoa of infertile males. High levels of free radicals disrupt the normal physiological functioning of spermatozoa, and ROS appears to have a range of variable effects on spermatozoa depending on the extent of oxidative stress [20].

Nanoparticles are widely employed and have been applied in a variety of therapeutic and diagnostic applications, including medication delivery systems, medical devices, food containers, and cosmetics. Among all nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are most frequently employed in dental alloy materials, catheters, and implant surfaces to treat infections associated with wounds and burns. Despite their potential benefits to society, biological adverse effects of AgNPs should be carefully evaluated since AgNPs can enter the human gastrointestinal tract by several routes (air, water, food) [21]. studies indicated that they also discovered accumulated in the blood and all examined organs, including the brain, testes, liver, heart, kidneys, spleen, thymus, and lungs [22].

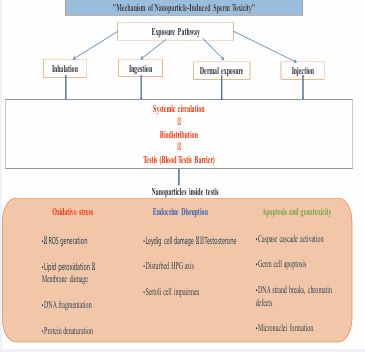

The induction of oxidative stress, or an imbalance between the production of ROS and their neutralization by antioxidants, is thought to be a major factor in NPs-induced injury both in vivo and in vitro. This imbalance is credited to either the presence of pro-oxidant functional groups on the reactive surfaces of the particles or to interactions between the nanoparticles and the cells. While ROS creation is a normal mechanism involved in many aspects of cellular signalling, excessive ROS formation by NPs has been shown to cause DNA damage, inflammation, protein denaturation, and lipid peroxidation, which have negative effects on cells [23] (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Mechanism of nanoparticle induced sperm toxicity.

As research advanced, it became clear that nanomaterials can cross the blood–brain and blood–testis barriers. These nanoparticles can accumulate in reproductive organs such as the testis, prostate, and epididymis via blood circulation or direct contact, leading to cytotoxic effects. In a previous study AgNPs has found to affect fertility and sperm function by reducing sperm production, increasing the number of abnormal spermatozoa, and causing germ cell damage in vivo [24]. AgNPs exposure significantly decreased the number of spermatogenic cells, including spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids and spermatozoa and also affected the acrosome reaction in sperm cells [25]. Research showed that Silica nanoparticles (SiNPs) can reduce serum testosterone levels, disrupt spermatogenesis, and damage testicular structure, leading to fewer and lower-quality sperm. The testes of exposed mice had a significantly higher ROS level, resulting in an oxidative redox imbalance. Compared to the control group, SiNP-exposed animals had a decrease in sperm count and motility. Mice treated with SiNPs had an increase in defective spermatozoa, with common anomalies including deformed heads, disconnected heads, twisted tails, and bent tails [26]. A study by Hasan [27], showed administration of CuO NPs dramatically increased the percentage of aberrant and dead sperm, depressed sperm concentration, and considerably decreased serum testosterone levels. The physiological traits of epididymal sperm and testicular function are negatively and permanently impacted by CuO NPs. Similarly, CuO NPs had a negative effect on sperm viability that varied with dose and time. The percentage of dead sperm rose in direct proportion to the dosage. A study found that oral administration of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) led to abnormal sperm count and motility in mice. ZnO NPs also reduced seminiferous tubule diameter, decreased the height of the seminiferous epithelium, and arrested germ cell development [28]. Daily oral administration of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) caused significant time dependent adverse effects, including as inflammation in testicular tissues, lipid peroxidation, decreased testis weight, and poor spermatogenesis. A 28-day oral administration caused sperm malformations, a sperm cell micronucleus rate, levels of markers linked to testicular cell damage, a further decrease in the number of germ cells and spherospermia, interstitial glands, and malalignment and vacuolization in spermatogenic cells. The effects on semen parameters were also recorded, demonstrating that normal sperm counts dropped in male mice’s testes and sperm quality after sperm quality [29].

According to a prior study, TiO2 NPs cause sperm DNA integrity to be lost and statistically significant increases in DNA fragmentation and strand breaks, which trigger apoptosis. In vitro, TiO2 NPs were genotoxic to human sperm cells, which had a major impact on the ability to reproduce [30].

Thus, the foregoing combined indicate that various forms of nanoparticles have dose- and time-dependent detrimental effects on sperm quality, with most of them involving pathways mediated by oxidative stress. The need to perform a comprehensive toxicological assessment before their extensive biomedical and modern industrial applications is expressed.

Sperm morphology

In addition to studying the morphology of normal and abnormal spermatozoa, the field of sperm morphology also looks into the possible link between infertility and sperm abnormalities. In sperm morphology, the identification and characteristics of various cellular elements are typically covered. The topic of sperm morphology is constantly changing and has been reassessed regularly to keep up with the growing body of scientific knowledge. The involvement of some isolated sperm abnormalities, such as spermatozoa lacking acrosomes or tails and only having “Pin-headed” spermatozoa, as a cause of infertility is widely accepted by researchers [31]. It is reasonable to assume that the environment surrounding fertilization and/or the female reproductive anatomy will have an impact on sperm morphology. The mysterious female choice is the source of the sperm phenotype [32]. From ≥ 80.5% in the first edition to ≥ 14% in the fourth, the reference value for normal sperm morphology reported in the various editions of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidelines for semen analysis dropped significantly. The fifth and sixth editions saw a drop of up to ≥4%. The fact that humans produce a higher percentage of faulty sperm than other animal species is supported and confirmed by these observations [33].

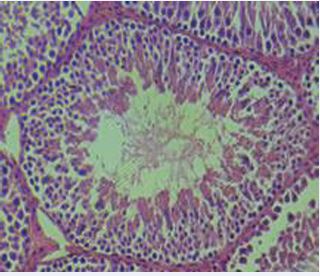

The normal rat testis consists of seminiferous tubules lined by a multilayered spermatogenic epithelium supported by Sertoli cells, surrounded by a thin basement membrane and myoid cells, with interstitial Leydig cells producing testosterone. Spermatogenesis progresses in a cyclical, stage-specific manner that is highly organized and species-characterized [34,35] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Histology of normal testis exhibiting normal germinal epithelium.

Some medicinal Plants that enhance fertility and sperm quality

Butea superba commonly known as Red Kwao Krua, belongs to Leguminosae family. The plant tubers have long been consumed as a traditional medicine for the promotion of male sexual vigor. It was observed alcoholic extract of Butea superba significantly increased the sperm concentration and delayed the decreased motility with time. [36]. Administration of powdered crude drug increase testis weight and sperm count in rats [37].

Cynomorium coccineum commonly known as Maitese mushroom, Desert thum, also known as Som-El-Ferakh in Saudi Arabia, which is a black leafless parasitic plant devoid of chlorophyll, belongs to Cynomoraceae family [38]. It is studied that Aqueous extract of Cynomorium coccineum induced significant increase in the sperm count, improved the percentage of live sperm and their motility, and decreased the number of abnormal sperm. Testicular histology showed increased spermatogenesis and seminiferous tubules full of sperm in the treated animals [39].

Mucuna pruriens is a popular Indian medicinal plant locally known as Kapikachu in Ayurveda and Konch in Hindi, belongs to Leguminosae family. The total alkaloids from the seeds of Mucuna pruriens were found to increase spermatogenesis and weight of the testes, seminal vesicles, and prostate in the albino rat [40]. The ethanolic extracts of Mucuna pruriens seed produced a significant and sustained increase in the sexual activity of normal male rats. There is significantly increased mounting frequency, intromission frequency and ejaculation latency and decreased mounting latency [41]. Mucuna pruriens efficiently recovered the spermatogenic loss induced due to ethinyl estradiol administration to rats. The recovery is mediated by reduction in ROS level, restoration of MMP, regulation of apoptosis, and eventual increase in the number of germ cells and regulation of apoptosis. The major constituent L-DOPA of Mucuna pruriens largely accounts for prospermatogenic properties [42].

Table 1: Nomenclature used in Andrology (Phadke, 2007).

|

1. |

Aspermia |

Absence of the ejaculate |

|

2. |

Azoospermia |

Absence of spermatozoa in the ejaculate. |

|

3. |

Hypospermia |

Abnormally low volume of the ejaculate. |

|

4. |

Hyperspermia |

Abnormally high volume of the ejaculate. |

|

5. |

Normozoospermia |

Normal ejaculate as per WHO standards (1999) |

|

|

Oligozoospermia: (severe) (mild) |

Sperm concentration < 10 × 106 /ml. Sperm concentration between 10 x 106/ml to 20 x 106 /ml. |

|

6. |

Asthenozoospermia |

Or

|

|

7. |

Teratozoospermia |

Increased number of spermatozoa with abnormal morphology. (Typically, > 50% abnormal forms) |

|

8. |

Oligoasthenoteratozoospermia |

Signifies disturbance of all three parameters. |

|

9. |

Necrozoospermia |

All the spermatozoa in the ejaculate are dead as confirmed by vital staining |

|

10. |

Polyzoospermia |

Means a very high concentration of spermatozoa in the ejaculate. (e.g. 250 × 10°/ml) |

|

11. |

Bacteriospermia |

Presence of a large number of bacteria in the semen. |

|

12. |

Pyospermia |

Presence of a large number of leukocytes in the semen. |

|

13. |

Hemospermia |

Presence of blood in semen. |

Tribulus terrestris commonly known as puncture vine is a perennial creeping herb with a worldwide distribution belongs to Zygophyllaceae family. Tribulus terrestris has long been used in the traditional Chinese and Indian systems of medicine for the treatment of various ailments and is popularly claimed to improve sexual functions. Administration of Tribulus terrestris to male lambs and rams improves plasma testosterone and spermatogenesis [43]. It also found to increase the levels of testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and dehydroepiandrosterone.

Withania somnifera commonly known as Ashwagandha belongs to Solanaceae family. It was observed Aqueous extract of Withania somnifera improved spermatogenesis, which may be due to increased interstitial cell stimulating hormone and testosterone-like effects as well as the induction of nitric oxide synthase [44]. Clinical Studies. Ashwagandha root extract administered to the oligospermic patients resulted in a significantly greater improvement in spermatogenic activity and serum hormone levels [45]. Treatment of infertile men with Withania somnifera inhibited lipid peroxidation and protein carbonyl content and improved sperm count and motility. It also recovered the seminal plasma levels of antioxidant enzymes Withania somnifera root powder when administered to normozoospermic infertile man resulted in a decrease in stress, improved the level of antioxidants, and improved overall semen and corrected fructose. Significantly increased serum T and LH and reduced levels of FSH and PRL in infertile men were observed [46].

A wide-ranging analysis explores the effects of various nutrients, supplements, and foods on sperm quality parameters. The meta-analysis demonstrated a significant positive impact on total sperm count from supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids and CoQ10(Coenzyme Q10). Furthermore, sperm concentration improved with the intake of selenium, zinc, omega-3, and CoQ10. Sperm motility was enhanced through supplementation with selenium, zinc, omega-3, CoQ10, and carnitines. Lastly, sperm morphology was positively influenced by supplementation with selenium, omega-3, CoQ10, and carnitines [47,48].

A clear beneficial effect on motility was found in trials using antioxidants – in particular carnitine, trace elements (zinc, selenium) and folic acid. The major effects on sperm concentration were found with anti-oestrogens, FSH and androgens. [49]. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) is essential for spermatogenesis, and both clinical and experimental studies have highlighted its critical role in regulating the process of spermatogenesis in mammals. FSH therapy may improve the quality and integrity of sperm organelles mainly the acrosome, nucleus and axoneme [50].

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) significantly enhances sperm quality, particularly when integrated with complementary treatments. This innovative therapy works by improving several critical parameters, including sperm density, motility, and viability. Additionally, it helps to reduce the prevalence of abnormalities in sperm morphology by increasing the oxygen concentration in the body [51]. The detrimental effect of an obesogenic diet on sperm quality, like sperm concentration and sperm motility, was reversed by the daily administration of ghrelin. Ghrelin treatment was done in male Wistar rats [52].

Microfluidic devices improve Sperm concentration, sperm vitality, morphology and sperm chromatin stability [53]. Myo-inositol therapy has a positive impact on several sperm parameters, including total and progressive sperm motility. This treatment suggests a favourable effect on these motility parameters. Additionally, Myo-inositol has been shown to have a beneficial effect in reducing DNA fragmentation, which is crucial for maintaining sperm DNA integrity [54].

Engineered exosomes enriched with GPX5 (Exo-GPX5) significantly improve sperm motility, enhance acrosome integrity, and increase total antioxidant capacity. They also exhibit a higher ability for capacitation and an increase in the acrosome reaction rate. As a cell-derived antioxidant additive, Exo-GPX5 offers a novel approach to improving the quality of boar semen preservation [55]. Cryopreservation of human semen, initially demonstrated in 1953, continues to be a fundamental aspect of fertility preservation. Its effectiveness depends on carefully regulated freezing and thawing, membrane integrity and pH balance-preserving cryoprotectants like glycerol, and extenders that maximise osmotic stability, provide energy, and minimise contamination. For sperm to remain viable and functionally competent during storage, cryoprotectants and extenders must be used in combined [56].

CONCLUSION

The widespread presence of male infertility underscores a critical public health concern that warrants comprehensive attention and intervention strategies. The multifaceted nature of this issue, attributed to environmental exposures, lifestyle choices, and physiological factors, illuminates the complexity surrounding male reproductive health. As outlined, the decline in semen quality due to factors such as air pollution, psychological stress, and dietary deficiencies calls for ongoing research and proactive measures. The use of medicinal plants and innovative therapies, such as engineered exosomes enriched with GPX5 and various nutrient supplements, highlights the potential for significant advancements in improving sperm quality. Meta-analyses have reinforced the beneficial role of omega-3 fatty acids, CoQ10, and essential trace elements, such as selenium and zinc, in enhancing sperm parameters, including motility, morphology, and overall count. In addition, nanotechnology-based approaches are emerging as promising tools in reproductive medicine. Nanoparticles, particularly plant-mediated, polymeric carriers, and lipid-based nanostructures, have shown potential for targeted delivery of antioxidants, hormones, and bioactive compounds directly to the testes or sperm microenvironment. While some studies caution against nanoparticle-induced toxicity that may impair spermatogenesis, controlled and biocompatible nanocarriers open new avenues for improving drug efficacy, minimizing side effects, and restoring male fertility. These insights pave the way for developing targeted dietary, nanotechnology-driven, and therapeutic interventions aimed at restoring male reproductive health.

Future prospects

Even so, this review includes the impact of several criteria on sperm quality as well as a thorough literature survey. Future research may examine if environmental pollutants and nanoparticles cause sperm to undergo heritable epigenetic changes that impact the health of the progeny. More mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate how these factors sperm at the molecular level (epigenetic changes, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction). Proteomic, metabolomic, and transcriptomic biomarkers offer promising tools for fertility assessment and should be validated across diverse populations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Head of the Department of Zoology for providing the required facilities for the completion of this review. We also acknowledge the funding agencies CSIR (SRF & JRF), UGC (SRF/JRF). Special thanks are extended to the institutions and libraries that provided access to scientific databases and resources essential for the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Kumar N, Singh AK. Impact of environmental factors on human semen quality and male fertility: a narrative review. Environ Sci Eur. 2022.

- Santolaria P, Rickard JP, Pérez-Pe R. Understanding Sperm Quality for Improved Reproductive Performance. Biology. 2023; 12 :980.

- Tanga BM, Qamar AY, Raza S, Bang S, Fang X, Yoon K, et al. Semen evaluation: methodological advancements in sperm quality-specificfertility assessment - A review. Animal bioscience. 2021; 34: 1253- 1270.

- Wang N, Gu H, Gao Y, Li X, Yu G, Lv F, et al. Study on Influencing Factorsof Semen Quality in Fertile Men. Front Physiol. 2022; 22: 813591.

- Deng Z, Chen F, Zhang M, Lan L, Qiao Z, Cui Y, et al. Association between air pollution and sperm quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution. 2016; 208: 663-669.

- Zhang J, Cai Z, Ma C, Xiong J, Li H. Impacts of Outdoor Air Pollution on Human Semen Quality: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. BioMed Res Int. 2020; 28: 7528901.

- Durairajanayagam D. Lifestyle causes of male infertility. Arab J Urol.2018; 16: 10-20.

- Yadav P, Mali PC. Testicular inflammation in male reproductive system. In Exploration of Immunology. 2024; 4: 446–464.

- Vaghela K, Oza H, MishraV, Gautam A, Kumar S. Effect of Lifestyle Factors on Semen Quality. Int J Life-Sci Scientific Res. 2016; 2: 627- 631

- Cao LL, Chang JJ, Wang SJ, Li YH, Yuan MY, Wang GF, et al. The effect of healthy dietary patterns on male semen quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In Asian J Androl. 2022 ; 24: 549-557

- Jurewicz J, Radwan M, Sobala W, Radwan P, Bochenek M, Hanke W. Dietary Patterns and Their Relationship with Semen Quality. Am J Men’s Health. 2018;12: 575-583.

- Salas-Huetos A, Bulló M, Salas-Salvadó J. Dietary patterns, foods and nutrients in male fertility parameters and fecundability: A systematic review of observational studies. Human Reproduction Update. 2017; 23: 371-389.

- Pinart E, Puigmulé M. Factors Affecting Boar Reproduction, Testis Function, and Sperm Quality. In: 2013: 109-202.

- Jurewicz J, Hanke W, Radwan M, Bonde JP. Environmental factors and semen quality. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2009; 22: 305-29.

- Sergeant N, Briand-Amirat L, Bencharif D, Delehedde, M. The sperm specific protein proAKAP4 as an innovative marker to evaluate sperm quality and fertility. 2019; 11: 1-6.

- Lotti F, Maggi M. Effects of diabetes mellitus on sperm quality andfertility outcomes: Clinical evidence. Andrology. 2023; 11: 399-416

- Yin T, Liang S, Zhou X, Lai X, Su X, Tao J, et al. The association of exposure to multiple metals with the risk of idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia: The mediating role of sperm chromatin, Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2025; 302: 118543.

- Klein JP, Mery L, Boudard D, Ravel C, Cottier M, Bitounis D. Impact of Nanoparticles on Male Fertility: What Do We Really Know? A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 29: 576.

- Araujo L, Sheppard M, Löbenberg R, Kreuter J. Uptake of PMMA nanoparticles from the gastrointestinal tract after oral administration to rats: modification of the body distribution after suspension in surfactant solutions and in oil vehicles. Int J Pharmaceutics. 1999; 176: 209-224.

- Agarwal A, Prabakaran S, Allamaneni S. What an andrologist/ urologist should know about free radicals and why. Urology. 2006; 67: 2-8.

- Wang E, HuangY, Du Q, Sun Y. Silver nanoparticle induced toxicity to human sperm by increasing ROS (reactive oxygen species) production and DNA damage. Environmental Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017; 52: 193-199.

- Khanna P, Ong C, Bay BH, Baeg GH. Nanotoxicity: an interplay ofoxidative stress, inflammation and cell death. Nanomaterials. 2015; 5: 1163-1180.

- Gromadzka-Ostrowska J, Dziendzikowska K, Lankoff A, Dobrzy?ska M, Instanes C, Brunborg G, et al. Silver nanoparticles effects on epididymal sperm in rats. Toxicology lett. 2012; 214: 251-258.

- Miresmaeili SM, Halvaei I, Fesahat F, Fallah A, Nikonahad N, Taherinejad M. Evaluating the role of silver nanoparticles on acrosomal reaction and spermatogenic cells in rat. Iranian J Reproductive Med. 2013; 11: 423.

- Guo Z, Wang X, Zhang P, Sun F, Chen Z, Ma W. Silica nanoparticles cause spermatogenesis dysfunction in mice via inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2022; 231: 113210.

- Hassan L, Hasan IM, Al-Amgad, Z, Ahmed H. Acute exposure to copper oxide nanoparticles impairs testicular function and sperm quality in adult male albino rats. SVU-Int J Vet Sci. 2024; 7: 1-21.

- Zhu L, Xue H, Hu H, Xue T, Chen K, Tang W, et al. The dual effects of nanomaterials on sperm and seminal fluid oxidative stress. Materials Today Bio. 2025; 34: 102163

- Santonastaso M, Mottola F, Iovine C, Cesaroni F, Colacurci N, RoccoL. In Vitro Effects of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) on Cadmium Chloride (CdCl2) Genotoxicity in Human Sperm Cells. Nanomaterials (Basel, Switzerland). 2020; 10: 1118.

- Santonastaso M, Mottola F, Colacurci N, Iovine C, Pacifico S, Cammarota M, et al. In vitro genotoxic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (n-TiO2) in human sperm cells. Molecular reproduction and development. 2019; 86: 1369-1377.

- Phadke AM. Clinical atlas of sperm morphology. Jaypee BrothersMedical Publishers Ltd. 2007.

- Prakash S, Prithiviraj E, Suresh S, Lakshmi NV, Ganesh MK, AnuradhaM. Morphological diversity of sperm: A mini review. In Iran J ReprodMed. 2014; 12: 239-242.

- Moretti E, Signorini C, Noto D, Corsaro R, Collodel G. The relevance of sperm morphology in male infertility. Frontiers in Reproductive Health. 2022; 4: 945351.

- Hasanin NA, Sayed NM, Ghoneim FM, Al-Sherief SA. Histological and Ultrastructure Study of the Testes of Acrylamide Exposed Adult Male Albino Rat and Evaluation of the Possible Protective Effect of Vitamin E Intake. J Microscopy and Ultrastructure. 2018; 6: 23.

- Yadav P, Bharti N, Sharma PK, Mali PC. “Cassia auriculata- derived silver nanoparticles as a novel male contraceptive agent”. Pharmacological Research - Modern Chinese Medicine. 2015; 15: 100626.

- Tocharus C, Jeenapongsa R, Teakthong T, Smitasiri Y. Effects of long-term treatment of Butea superba on sperm motility and concentration, Naresuan University J. 2005; 1: 11-17.

- Manosroi A, Sanphet K, Saowakon S, Aritajat S, Manosroi J. Effects of Butea superba on reproductive systems of rats. 2006; 6: 435-438

- Ageel AM, Mossa JS, Tariq M, Al-Yahya MA, Al-Said MS, Saudi Plants Used in Folk Medicine, Department of Scientific Research, King Abdel- Aziz City for Science and Technology. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 1987.

- Abd el-Rahman HA, el-Badry AA, Mahmoud OM, Harraz FA. The effect of the aqueous extract of Cynomorium coccineum on the epididymal sperm pattern of the rat. Phytotherapy Res. 1999; 13: 248-250.

- Saksena S, Dixit VK. Role of total alkaloids of Mucuna pruriens Baker in spermatogenesis in Albino rats. Indian J Natural Products. 1987; 3: 3-7.

- Suresh S, Prithiviraj E, Prakash S. Effect of Mucuna pruriens onoxidative stress mediated damage in aged rat sperm. Int J Androl.2010; 1: 22-32,

- Singh AP, Sarkar S, Tripathi M, Rajender S. Mucuna pruriens and its major constituent L-DOPA recover spermatogenic loss by combating ROS, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis. PLoS ONE8. 2013; 8: e54655,

- Georgiev P, Dimitrov M, Vitanov S. Effect of Tribestan (from Tribulus terrestris) on plasma testosterone and spermatogenesis in male lambs and rams, Veterinarna Sbirka. 1988; 86: 20-22.

- Iuvone T, Esposito G, Capasso F, Izzo AA. Induction of nitric oxide synthase expression by Withania somnifera in macrophages. Life Sciences. 2003; 14: 1617-1625

- Ambiye VR, Langade D, Dongre S, Aptikar P, Kulkarni M, Dongre A. Clinical evaluation of the spermatogenic activity of the root extract of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) in oligospermic males: a pilot study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013; 571420,

- Ahmad MK, Mahdi AA, Shukla KK, Islam N, Rajender S, Madhukar D, et al. Withania somnifera improves semen quality by regulating reproductive hormone levels and oxidative stress in seminal plasma of infertile males. Fertility and Sterility. 2010; 94: 989–996

- Salas-Huetos A, Rosique-Esteban N, Becerra-Tomás N, Vizmanos B, Bulló M. The effect of nutrients and dietary supplements on sperm quality parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Adv Nutr. 2018; 9: 833-848.

- Imhof M, Lackner J, Lipovac M, Chedraui P, Riedl C. Improvement of sperm quality after micronutrient supplementation. e-SPEN J. 2012; 7; e50-e53.

- Isidori AM, Pozza C, Gianfrilli D, Isidori A. Medical treatment to improve sperm quality. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2006; 12: 704-714.

- Ben Rafael Z, Farhi J, Feldberg D, Bartoov B, Kovo M, Eltes F, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone treatment for men with idiopathic oligoteratoasthen ozoospermia before in vitro fertilization: the impact on sperm microstructure and fertilization potential. Fertility and Sterility. 2000; 73: 24–30.

- Bang L, Jin W, Lvjun L, Mengmei L, Dai1 Z, Min L. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for male infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis on improving sperm quality and fertility outcomes. Medical Gas Res. 2025; 15: 529-534.

- Luque EM, Carlini VP, Guantay P, Machuca D, Torres P, Ramírez N, et al. Ghrelin treatment and exercise improve sperm quality in rats fed an obesogenic diet: A potential link to LEAP2. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2025; 607: 112608.

- Meseguer F, Rodríguez CG, Egea RR, Sisternas LC, Remohí JA, Meseguer M. Can microfluidics improve sperm quality a prospective functional study. Biomed. 2024; 12: 1131.

- Ghaemi M, Seighali N, Shafiee A, Beiky M, Kohandel Gargari O, Azarboo A, The effect of Myo- inositol on improving sperm quality and IVF outcomes: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Food Sci Nutr. 2024; 12: 8515-8524.

- Huang J, Li S, Yang Y, Li C, Zuo Z, Zheng R, et al. GPX5-enriched exosomes improve sperm quality and fertilization ability. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25: 10569.

- Telang M. Atlas of human assisted reproductive technologies. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd. 2007.