Frequency of Female Sexual Dysfunction among Healthcare Givers in Hospitals Dealing with Patients with COVID-19 during the First Pandemic Wave in Egypt

- 1. Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Fayoum University, Egypt

- 2. Public Health Community Medicine Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University, Egypt

- 3. Department of Medicine, Hepatology and Gastroenterology, National Liver Institute, Menoufia University, Egypt

Abstract

Background: Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is described as difficulty experienced by females during any stage of sexual activity. The FSD was extensively studied previously during COVID-19 outbreak, however healthcare givers dealing with patients tested positive were not addressed.

Aim: Was to assess the impact of being a female healthcare givers working in hospitals dealing with patients with Covid-19 during first outbreak- on sexual function (SF) with identification of associated risk factors.

Methods: 231 healthcare givers working in hospitals dealing with COVID-19 patients during the first pandemic wave and 123 females working in non-medical jobs as a controls were included. The self-administered International Index of Female sexual (FSFI) questionnaire was completed by all participants during the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 in Egypt. The results of FSFI were compared to controls

Main Outcome Measure: We determined the proportions of patients and controls who were dissatisfied with their sexual life, the impact of disease and cure on the total FSFI score and scores domains.

Results: There was no statistically significant difference (p-value > 0.05) between both groups as regards age, residence and place of work while. Healthcare givers significantly scored lower results of mean of FSFI and its domains (lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain). Female nurses had lower results of mean of FSFI and its domains (lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) than female doctors.

Clinical Implications: Given the high prevalence of FSD among healthcare givers, it is recommended that SF in female healthcare givers should be addressed as psychosocial support to the quality of life in that will in turn positively affect health outcomes.

Strengths & Limitations: This is the first study to report on FSD in healthcare givers in hospitals dealing with COVID-19 patients during the first pandemic wave. Sub-analysis of data in female physicians and female nurses was done.

Conclusion: Female medical stuff working in isolation hospitals experienced sexual dysfunction affecting FSFI (total and most domains). The sexual burdens and psychosocial aspects associated with COVID-19 among healthcare givers are underestimated because of the standard focus on daily medical practices in these hospitals.

KEYWORDS

- Sexual function in era of COVID-19

- Occupational impact

- Stress

- Burnout

- Psychiatric illnesses

- Quality of life

CITATION

Mohamad NE, Abdelmeguid YS, Elsary AY, Elshimi E (2021) Frequency of Female Sexual Dysfunction among Healthcare Givers in Hospitals Dealing with Patients with COVID-19 during the First Pandemic Wave in Egypt. JSM Sexual Med 5(3): 1075.

INTRODUCTION

As a particular occupational population, doctors undertake the mission of curing patients and exposure to diseases, death, emergency which is believed to lead to a high level of occupational stress. Additionally, stress from night shift work, overtime, and other occupational characteristics, such as chemical exposure, radiation sources, musculoskeletal strain and disorders can affect the mental and physical health of doctors [1].

During the first wave of Covid-19 pandemic in the end of 2019 and start of 2020, healthcare givers in hospitals dealing with corona virus patients, were in close contact with infected patients during outbreak. It had been found that 35.5% of them were found positive for Covid- 19, based on PCR test [2]. In the general population, around 5 million people in the globe have been infected and at least, the number of deaths exceeded 300,000 worldwide [3].

During the first pandemic outbreak of Covid-19, great social isolation had been found, and this led to simultaneous wave of panic and fear. This led to further depression and sexual dysfunction. The behavioral attitudes and sexual health of the female healthcare givers who were in contact with the infected patients are unknown.

Sexual transmissions of Covid-19 is still questionable, there is no sufficient evidence supportive of viral isolation in vaginal secretions and semen [4]. However, the presence of the virus within body fluids is well known and close contact during sexual relationships may favor of viral transmission.

During the first wave of pandemic, female healthcare givers may be strongly concerned about getting infected from hospitals dealing with corona patients and transmitting the virus to their families, especially husbands during coitus.

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is described as difficulty experienced by a female during any stage of a normal sexual activity including physical pleasure, desire, arousal, or orgasm. There are various factors responsible for FSD including psychological status of a person, gynecological or medical problems, long use of certain drugs, and social beliefs [5]. These risk factors and potential causes collectively or separately may interfere enough to significantly resulting in sexual dysfunction.

Moreover, epidemiological researchers have found associations between FSD and many personal characteristics, such as age, marital status, education, family income, physical and mental health problems [6].

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) has been designed to assess the female sexual function [7]. Its questionnaire includes 19 items that evaluate six domains of female sexual response cycle (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain). The FSFI was previously validated in a study of sexual arousal disorder in women using matched controls [8]. Its Arabic version is available (ArFSFI) [9] and has been used in many studies [10,11] to assess sexual function (SF).

STUDY OUTCOMES

The first evaluated outcomes were the proportion of doctors, nurses and controls who were dissatisfied with their sexual life and the impact of healthcare giving in hospitals dealing with Corona virus during first wave pandemics in Egypt on SF. Secondary outcomes included the mean scores for each FSFI domains and the impact of working hospital dealing with patients with corona virus during first pandemic wave.

Study design

Subjects: This study was an analytical cross-sectional study that carried out at Fayoum University hospitals and National Liver Institute Menoufia University hospital, both centers were well equipped and hence they were used as isolation center to treat patients having COVID-19 during the first wave of outbreak.

Inclusion criteria: This study included two groups: female healthcare givers and controls. Between May 2020 and August 2020, we evaluated 104 female doctors and 127 female nurses working in the isolation departments in hospital dealing with Corona patients during first Covid-19 outbreak in Egypt.

All included participants were married and sexually active. No clinical or laboratory indices of advanced systemic affection were detected.

We also recruited 123 female controls during the same period. All controls lacked any signs or symptoms of systemic diseases.

Exclusion criteria were: age below 18 years or above 55 years. Moreover, participants with diagnosed depression were also excluded, using the Arabic version of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) [12].

METHODS

1. Assessment of socio-demographic & general medical data:

Each participant was asked about demographic characteristics including age, educational level, marriage age and occupational status, menstrual cycle or menopause status, previous pregnancies and contraception methods. The husband attitude and characteristic were also discussed with each participant.

2.Occupational risk factors:

Risk factors, associated with health and lifestyle, including occupational stressors as night shifts and hours of work, and exposure to occupational hazards as infection radiation, exposure of mental and physical efforts were assessed in both groups and furthermore, these items were reassessed among female doctors and female nurses subgroups.

3. Assessment of Sexual Function:

Studied participants, were interviewed by a trained female researcher and were asked to sign an Arabic consent form in the presence of the one of the authors. All participants (medical stuff and controls) were sexually active during last four weeks.

We documented in the consent that all answers would be anonymous, and the data would be only used for research and presented only in scientific journals.

Sexual function was assessed by the Arabic version of the FSFI during the first week of Covid-19 outbreak. The results of medical stuff were compared with those of non-medical participants.

Statistical analysis of data

The collected data were organized, tabulated and statistically analyzed using SPSS software statistical computer package version 22 (SPSS Inc, USA). For quantitative data, the mean standard deviation (SD) calculated. Independent t-test or One- way ANOVA was used in comparing between any two groups or three groups, respectively. Qualitative data were presented as number and percentages, chi square (χ2) was used as a test of significance. Pearson correlation was performed to determine the relation between FSFI and study parameters among cases. For interpretation of results of tests of significance, significance was adopted at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 illustrated that there was no statistically significant difference (p-value > 0.05) between medical stuff group and non-medical group as regards age, residence and place of work while, the educational level, additional jobs and exposure to occupational hazards were significant (p-value < 0.05).

|

Table 1: Comparisons of demographic and work characters in different study groups. |

|||||

|

Variables |

Medical (N=213) |

Non-medical (n=123) |

P-value |

||

|

Age (years) |

|

||||

|

Mean /SD |

33.9 |

7.5 |

34.8 |

7.7 |

0.1 |

|

Residence |

|

||||

|

Rural |

107 |

46.3% |

67 |

54.5% |

0.14 |

|

Urban |

124 |

53.7% |

56 |

45.5% |

|

|

Education level |

|

||||

|

Medical doctorate |

5 |

2.2% |

7 |

5.7% |

<0.001* |

|

Master degree |

60 |

26% |

40 |

32.5% |

|

|

Bachelor |

69 |

29.9% |

15 |

12.2% |

|

|

Middle level |

97 |

42% |

61 |

49.6% |

|

|

Place of work |

No. (%) |

No. (%) |

|

||

|

Public |

161 |

69.7% |

97 |

78.9% |

0.08 |

|

Public & private |

70 |

30.3% |

26 |

21.1% |

|

|

Have additional job |

|

||||

|

Yes |

73 |

31.6% |

26 |

21.1% |

0.04* |

|

No |

158 |

68.4% |

97 |

78.9% |

|

|

Occupational hazards in form of exposure to |

|||||

|

Extra work |

141 |

61% |

9 |

7.3% |

<0.001* |

|

Chemicals |

127 |

55% |

11 |

8.9% |

<0.001* |

|

High Physical effort |

187 |

81% |

117 |

95.1% |

<0.001* |

|

High Mental effort |

195 |

84.4% |

123 |

100% |

<0.001* |

|

Infection |

200 |

86.6% |

1 |

0.8% |

<0.001* |

|

Sexual harassment |

26 |

11.3% |

4 |

3.3% |

0.01* |

Table 2 illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference (p-value <0.05) between study groups with younger age of marriage,

|

Table 2: Comparisons of gynecological and husband characters in the study groups. |

|||||

|

Variables |

Medical (N=213) |

Non-medical (n=123) |

P-value |

||

|

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

|

||

|

Age of marriage (yrs) |

22±4.1 |

25.5±4.7 |

<0.001* |

||

|

Duration of marriage (yrs) |

12.1±8.9 |

12.2±7.9 |

0.9 |

||

|

Number of offspring |

2.4±1.6 |

3.5±1.2 |

<0.001* |

||

|

Number of abortions |

1±1 |

1.6±0.5 |

<0.001* |

||

|

Menstrual cycle |

|

||||

|

Regular |

170 |

73.6% |

68 |

55.3% |

0.001* |

|

Irregular |

36 |

15.6% |

39 |

31.7% |

|

|

No menses |

25 |

10.8% |

16 |

13% |

|

|

Use contraception methods |

|

||||

|

Yes |

130 |

56.3% |

59 |

48% |

0.14 |

|

No |

101 |

43.7% |

64 |

52% |

|

|

Do circumcision |

|

||||

|

Yes |

141 |

61% |

115 |

93.5% |

<0.001* |

|

No |

90 |

39% |

8 |

6.5% |

|

|

Degree of circumcision |

|

||||

|

Grade I |

56 |

39.7% |

112 |

97.4% |

<0.001* |

|

Grade II |

85 |

60.3% |

3 |

2.6% |

|

|

Husband educational level |

|||||

|

Illiterate |

5 |

2.2% |

1 |

0.8% |

<0.001* |

|

Primary |

10 |

4.3% |

26 |

21.1% |

|

|

Preparatory |

17 |

7.4% |

9 |

7.3% |

|

|

Middle |

57 |

24.7% |

63 |

51.2% |

|

|

University |

142 |

61.5% |

24 |

19.5% |

|

|

Husband work |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

202 |

87.4% |

110 |

89.4% |

0.7 |

|

No |

29 |

12.6% |

13 |

10.6% |

|

|

Smoker |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

114 |

49.4% |

42 |

34.1% |

0.007* |

|

No |

117 |

50.6% |

81 |

65.9% |

|

|

Problems in erection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

13 |

5.6% |

0 |

0% |

<0.001* |

|

No |

196 |

84.8% |

123 |

100% |

|

|

Sometimes |

22 |

9.5% |

0 |

0% |

|

|

Problems in ejaculation |

|||||

|

Yes |

11 |

4.8% |

0 |

0% |

<0.001* |

|

No |

188 |

85.7% |

123 |

100% |

|

|

Sometimes |

22 |

9.5% |

0 |

0% |

|

|

Husband satisfied with sexual relation |

|||||

|

Yes |

120 |

51.9% |

103 |

83.7% |

<0.001* |

|

No |

46 |

19.9% |

12 |

9.8% |

|

|

Sometimes |

65 |

28.1% |

8 |

6.5% |

|

|

Emotional problems with husband |

|||||

|

Yes |

48 |

20.8% |

20 |

16.3% |

0.32 |

|

No |

183 |

79.2% |

103 |

83.7% |

|

|

Husband receive treatment for sexual problems |

|||||

|

Yes |

30 |

13% |

12 |

9.8% |

0.39 |

|

No |

200 |

87% |

111 |

90.2% |

|

|

Husband receive treatment for any health problems |

|||||

|

Yes |

32 |

13.9% |

21 |

17.1% |

0.44 |

|

No |

199 |

86.1% |

102 |

82.9% |

|

lower number of offspring and abortion amongst medical group. In addition, non-medical staff showed significantly higher percentage of irregular menstrual cycle, pregnancy, normal vaginal delivery, and circumcision with grade I. but no statistical significance difference as regards marriage duration, and using contraception methods.

The table also illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference (p-value <0.05) between study groups with higher percentage of high husband educational level, smokers with erection and ejaculation problems in addition to lower sexual satisfaction level among healthcare givers group.

On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value >0.05) as regards husband work, emotional problems or health problems including sexual health problems.

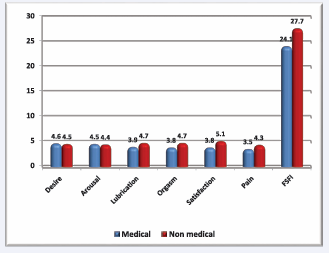

Figure 1,

Figure 1: Showed that there was a statistically significant difference (p-value 0.05) between groups as regards desire and arousal domain of FSFI score.

illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference (p-value <0.05) between study groups (healthcare givers and non-medical groups) with lower mean of FSFI and its domains (lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) among medical staff. On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value >0.05) between groups as regards desire and arousal domain of FSFI score.

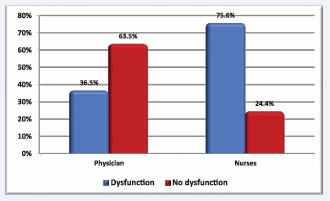

Figure 2,

Figure 2: Illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference (p-value 0.05) between them as regards domain of desire of FSFI score.

v illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference (p-value <0.05) between physicians and nurses; female nurses lower mean of FSFI and its domains (lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain). On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value >0.05) between them as regards domain of desire of FSFI score.

Female physicians with sexual dysfunction had lower number of work shifts and night shifts per weeks, worked in public places, had no additional work. On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference ( p-value >0.05) as regards number of work hours per weeks, and exposure to any of occupational hazards in form of extra work, chemicals, radiation, physical and mental effort, infection in addition to sexual harassment (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Comparisons of sexual dysfunction in different occupation characters among physicians. |

|||||

|

Variables |

Sexual dysfunction |

P-value |

|||

|

Yes (N=38) |

No (N=66) |

||||

|

Number of |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

|

||

|

Work hours/ day |

6.3±1.4 |

6.6±2.5 |

0.4 |

||

|

Work shifts / week |

0.29±0.5 |

0.74±1.1 |

0.02* |

||

|

Night shifts / week |

1±0 |

2.4±1.2 |

0.02* |

||

|

Place of work |

No . (%) |

No . (%) |

|

||

|

Public |

34 |

89.5% |

41 |

62.1% |

0.003* |

|

Public & private |

4 |

10.5% |

25 |

37.9% |

|

|

Have additional job |

|

||||

|

Yes |

4 |

10.5% |

25 |

37.9% |

0.003* |

|

No |

34 |

89.5% |

41 |

62.1% |

|

|

Have night shifts |

|

||||

|

Yes |

6 |

15.8% |

11 |

16.7% |

0.9 |

|

No |

32 |

84.2% |

55 |

83.3% |

|

|

Occupational hazards in form of exposure to |

|

||||

|

Extra work |

8 |

21.1% |

12 |

18.2% |

0.8 |

|

Chemicals |

2 |

5.3% |

7 |

10.6% |

0.5 |

|

Radiations |

6 |

15.8% |

7 |

10.6% |

0.5 |

|

High Physical effort |

24 |

36.8% |

30 |

45.5% |

0.4 |

|

High Mental effort |

29 |

76.3% |

41 |

62.1% |

0.2 |

|

Infection |

28 |

73.7% |

51 |

77.3% |

0.8 |

|

Huge patients number |

22 |

57.9% |

42 |

63.6% |

0.7 |

|

Sexual harassment |

2 |

5.3% |

0 |

0% |

0.1 |

Female nurses with sexual dysfunction had lower number of work hours per day and work shifts per weeks, worked in public places, had no additional work, and no night shifts. As regards exposure to occupational hazards, there was a statistically significant difference with higher percentage of exposure to extra work, radiation, and infection, but no effect of exposure to chemicals, physical and mental effort in addition to sexual harassment (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Comparisons of sexual dysfunction in different occupation characters amongst nurse. |

|||||

|

Variables |

Sexual dysfunction |

P-value |

|||

|

Yes (N=96) |

No (N=31) |

|

|||

|

Number of |

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

|

||

|

Work hours/ day |

7.5±1.9 |

8.7±2.1 |

0.003* |

||

|

Work shifts / week |

1.7±1.5 |

3.1±1.8 |

<0.001* |

||

|

Night shifts / week |

1.6±1.5 |

1.7±0.7 |

0.8 |

||

|

Place of work |

No . (%) |

No . (%) |

|

||

|

Public |

75 |

78.1% |

11 |

35.5% |

<0.001* |

|

Public & private |

21 |

21.9% |

20 |

64.5% |

|

|

Have additional job |

|

||||

|

Yes |

24 |

25% |

20 |

64.5% |

<0.001* |

|

No |

72 |

75% |

11 |

35.5% |

|

|

Have night shifts |

|

||||

|

Yes |

42 |

43.8% |

24 |

77.4% |

0.002* |

|

No |

54 |

56.3% |

7 |

22.6% |

|

|

Occupational hazards in form of exposure to |

|

||||

|

Extra work |

94 |

97.9% |

27 |

87.1% |

0.03* |

|

Chemicals |

91 |

94.8% |

27 |

87.1% |

0.2 |

|

Radiations |

62 |

64.6% |

13 |

41.9% |

0.03* |

|

High Physical effort |

96 |

100% |

31 |

100% |

---- |

|

High Mental effort |

96 |

100% |

29 |

93.5% |

0.06 |

|

Infection |

94 |

97.9% |

27 |

87.1% |

0.03* |

|

Huge patients number |

94 |

97.9% |

29 |

93.5% |

0.6 |

|

Sexual harassment |

19 |

19.8% |

5 |

16.1% |

0.8 |

Table 5: The linear logistic regression model analysis was conducted to explore the explanatory power of different occupational risk factors on sexual dysfunction, it illustrated that there was statistical significance predictors (p-value <0.05) to work shifts / week, have additional job, and exposure to high physical effort

|

Table 5: Logestic regression analysis to determine the prediction power of different occupational factors in occurrence of sexual dysfunction. |

||||

|

Variables |

B |

SE |

RR |

Significance |

|

Work hours/ day |

0.49 |

0.28 |

1.1 |

0.08 |

|

Work shifts / week |

2.9 |

0.82 |

18.9 |

<0.001* |

|

Night shifts / week |

-1.2 |

0.66 |

0.31 |

0.08 |

|

Place of work |

0.12 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

|

Have additional job |

8.8 |

2.9 |

6718.4 |

0.003* |

|

Occupational hazards in form of exposure to |

||||

|

Chemicals |

0.14 |

2.2 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

|

Radiations |

1.4 |

0.77 |

4.2 |

0.06 |

|

High Physical effort |

8.7 |

2.8 |

6142.5 |

0.002* |

|

High Mental effort |

-0.23 |

2.6 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

|

Infection |

-1.9 |

1.8 |

0.15 |

0.3 |

|

Huge patients number |

0.11 |

2 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

|

Sexual harassment |

-1.4 |

0.99 |

0.24 |

0.2 |

DISCUSSION

The aim of this cross sectional controlled study was to assess the impact of working as a healthcare giver in hospital dealing with Covid-19 during the first outbreak on female sexual function with identification of associated risk factors.

The first reported case in Egypt was in February 2020. Subsequently, the number has been rising and the reported fatality rate was 4.8% [13].

During the first pandemic outbreak of COVID-19 in Egypt, the Ministry of Health, designed special hospitals to deal with Corona patients, with increasing number of cases, the Ministry of Health specified isolated departments in well-equipped general hospitals to treat such patients.

Thousands of Egyptian Healthcare givers including female medical staff have been assigned to acute care departments such as intensive care units or emergency rooms to fight in frontlines and work in hospitals and centers specialized in dealing with Corona patients.

During the first wave of pandemic COVID-19 outbreak, Medical staff has to work hard and spend a lot of time and effort to deal COVID-19. They faced lot of numerous life and social quarrels. Colleagues in the same hospital and family members, sometimes refused to share them food and drinks as a panic response from getting infected. Moreover the medical staff faced also social isolation among their families, that can led to widespread panic and anxiety, with further negative impact on SF.

We designed our study and included only female participants either healthcare givers or women working in non-medical jobs. Given the hormonal [14,15], psychosocial, [16] and anatomic [17] differences between men and women, it is more appropriate to study the SF of both genders in separate studies with different measurement scales. Based on this, we designed the present study to include only female healthcare givers and dealing with infected patients with Corona virus and women working in non-medical jobs as controls. Participants suffering from any disorders that can affect SF as chronic diseases and depression were excluded.

Our study included 231 married and sexually active females working as medical staff, they were subdivided into 104 female doctors and 127 female nurses. We compared them versus 123 females who are working in non-medical jobs. Studied participants aged between 18 and 50 years old. There was a statistically significant difference among study groups as regards educational level with higher level among physician. On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference as regards age.

Female healthcare givers, scored more sexual dysfunction (58%) than non-medical participants (41.5%%) with lower mean FSFI domains (lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain). On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference was found between both groups in desire and arousal domains.

During the first wave of COVID-19 outbreak, the rate of spread appears to be quite high that leads to severe psychosocial stress for medical stuff especially who were working in the frontline to deal with Corona patients. Possible reasons to explain our findings include the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare givers. This was proved in similar study conducted during the outbreak of SARS in 2003 [18]. In another study, healthcare givers experienced during COVID-19 outbreak stress in 29.8%, anxiety in 24.1%, and depression in 13.5% [19]. The psychology of healthcare givers has been investigated in another study. The healthcare givers with sexual dysfunction had significantly higher percentage of anxiety than non with normal sexual life. In addition, female healthcare givers were more vulnerable to anxiety and hence experienced more sexual dysfunction than male healthcare givers [20]. We believe that the stigmatization associated with the first wave of COVID-19 has a crucial role.

Another explanation could be concluded clearly from our study came from the significant difference between both groups in regards to the higher percentage of having additional work amongst medical group with exposure to different medical occupational hazards in form of chemicals, radiation, physical effort, infection and sexual harassment.

Numerous clinical studies have documented the impact of COVID-19 on sexual life, either in women in general population [21-25] or on health care givers [26-29]. Two studies have documented the SD among female healthcare professional [28,29] with potential contributing factors associated with COVID-19 outbreak. However the aforementioned two studies lacked the assessment of the impact of dealing with COVID-19 patients like ours.

In our study, we have found significant differences between female doctors and female nurses in regards to sexual function, female nurses significantly scored lower sexual function values in the domines of arousal, lubrication, satisfaction and orgasm as well as the total score of FSFI. In our study, female nurses in Egypt are usually more susceptible to stress, lower income and more husband partner problems than female doctors.

In our study, female physicians with sexual dysfunction had lower number of work shifts and night shifts per weeks, worked in public places, had no additional work. On the other hand, there was no statistically significant difference (p-value >0.05) as regards number of work hours per weeks, and exposure to any of occupational hazards. Female nurses with sexual dysfunction had lower number of work hours per day and work shifts per weeks, worked in public places, had no additional work, and no night shifts. As regards exposure to occupational hazards, there was a statistically significant difference with higher percentage of exposure to extra work, radiation, and infection among the group with SD, but no effect of exposure to chemicals, physical and mental effort in addition to sexual harassment.

Farah et al. [29], documented high prevalence of female sexual dysfunction (56%) in Singapore, this looks like our findings. However in their study, nurses scored better results than female doctors unlike our results. They documented high prevalence of female sexual dysfunction (56%) among healthcare professionals in Singapore like our findings. Based on our findings, female nurses were exposed to more occupational hazards and worked more time and night shifts than female doctors.

Our data showed that, participants among nurses and doctors with sexual dysfunction had significantly more workhours, exposure to infection, radiation, more physical efforts and caring larger number of patients.

To our knowledge, our case control study is the first to estimate the impact of dealing with patients, known to have COVID-19 infection during the first pandemic wave in Egypt.

Much strength in this study worth a mention; 1) it is the first study among Egyptian female healthcare givers during the first wave of outbreak of COVID-19, second, we excluded participants with diseases that affect the sexuality, such as liver disease, depression, ischemic heart disease and diabetes, third, we used the detailed version of the FSFI questionnaire. Moreover, we compared the results of female doctors to those of female nurses. Another major strength is that, the perception and attitude of the male partners were included and addressed; in the Egyptian community and in almost all cases, although, the partners refused to voice their sexual status in many previous similar studies even with male health care assistants [10,11].

One of the major limitation in this study included that the sexual function after end of first wave of outbreak was not studied based on the non-compliance of participants.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, female medical professionals working in hospitals dealing with patients with COVID-19, experienced sexual dysfunction, that affecting the all FSFI domains. The sexual burdens and psychosocial aspects associated with COVID-19 among female healthcare givers are underestimated because of the standard focus on daily medical work practices in hospitals dealing with patients with corona virus. Female nurses experienced more stresses and developed more sexual dysfunction than female doctors. These findings worth putting in consideration as during outbreaks, healthcare givers have to stay in frontline to fight against COVID-19 outbreaks.

For better clinical standards, it is recommended addressing the quality of life aspects. The major possibilities of further waves of COVID-19 in futures necessitate social supports for healthcare giver to cope with stigmatizations burdens. Finally, perception and practice of society towards healthcare providers should be changed. Finally, the sexual function in medical stuff is in need for further re-evaluation during next COVID-19 epidemics.

Ethical approval and consent

This study was conducted in according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol approved by the ethics committee of Würzburg University and by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Fayoum University (IRB number IRB00003613) in January 2018. An informed written Arabic consent form was signed by every participant in the presence of one of the authors. The consent form stated that the answers of questionnaire would be anonymous and the obtained results would be used only for the current study and to be used only for scientific purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all support staff in outpatients’ clinics of leprology hospitals.

REFERENCES

- Li W, Li S, Lu P, Haibin Chen, Yunyu Zhang, Yu Cao, et al. Sexual dysfunction and health condition in Chinese doctor: prevalence and risk factors. Scientific Reports. 2020; 10: 1-9

- Amy Heinzerling, Matthew J Stuckey, Tara Scheuer, Kerui Xu, Kiran M Perkins, Heather Resseger, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 to Health Care Personnel During Exposures to a Hospitalized Patient – Solano County, California, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69: 472-6.

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Paoli D, Pallotti F, Colangelo S, F Basilico, L Mazzuti, O Turriziani, et al. Study of SARS-CoV-2 in semen and urine samples of a volunteer with positive naso-pharyngeal swab. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020; 43: 1819-22.

- Mishra VV, Nanda S, Vyas B, Rohina Aggarwal, Sumesh Choudhary, Suwa Ram Saini, et al. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction among Indian fertile females. J Midlife Health. 2016; 7: 154.

- Christensen BS, Grønbæk M, Osler M, Bo Vestergaard Pedersen, Christian Graugaard, Morten Frisch, et al. Associations between physical and mental health problems and sexual dysfunctions in sexually active Danes. J Sex Med. 2011; 8: 1890-1902.

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, S Leiblum, C Meston, R Shabsigh, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self- report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000; 26: 191–208.

- Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005; 31: 1-20.

- Anis TH, Gheit SA, Saied HS, Samar A.Al kherbash. Arabic translation of female sexual function index and validation in an Egyptian population. J Sex Med. 2011; 8: 3370-3378.

- Elshimi E, Morad W, Mohamad NE, Nashwa Shebl, Imam Waked. Female sexual dysfunction among Egyptian patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Sex Med. 2014; 11: 768-775.

- Elshimi E, Sakr N, Morad W, Noha Ezzat Mohamad, Imam Waked. Direct-acting antiviral drugs improve the female sexual burden associated with chronic HCV infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019; 17: 919-926.

- Terkawi AS, Tsang S, AlKahtani GJ, Sumaya Hussain Al-Mousa, Salma Al Musaed, Usama Saleh AlZoraigi, et al. Development and validation of Arabic version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017; 11: S11–S18.

- Egypt Care: Corona Virus in Egypt [cited 2020 15 July].

- Ingman WV, Robertson SA. Transforming growth factor-beta1 null mutation causes infertility in male mice associated with testosterone deficiency and sexual dysfunction. Endocrinology. 2007; 148: 4032-4043.

- Govier FE, McClure RD, Kramer-Levien D. Endocrine screening for sexual dysfunction using free testosterone determinations. J Urol. 1996; 156: 405-408.

- Stoléru S, Fonteille V, Cornélis C, Christian Joyal, Virginie Moulier. Functional neuroimaging studies of sexual arousal and orgasm in healthy men and women: A review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012; 36: 1481-1509.

- Poeppl TB, Langguth B, Rupprecht R, Adam Safron, Danilo Bzdok, Angela R Laird. The neural basis of sex differences in sexual behavior: A quantitative meta-analysis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2016; 43: 28-43.

- Chen NH, Wang PC, Hsieh MJ, Chung-Chi Huang, Kuo-Chin Kao, Ya-Hui Chen, et al. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome care on the general health status of healthcare workers in taiwan. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007; 28: 75-9.

- Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 288: 112936.

- Yin Q, Sun Z, Liu T, Ni X, Deng X, Jia Y, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms of Health Care Workers during the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020; 27: 384-95.

- Omar SS, Dawood W, Eid Noha, Dalia Eldeeb, Amr Munir, Waleed Arafat. Psychological and Sexual Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Egypt: Are Women Suffering More?. Sex Med. 2021; 9: 100295.

- Bhambhvani H, Chen T, Kasman M, Wilson-King G, Ekene Enemchukwu, Michael L Eisenberg. Female Sexual Function During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Sex Med. 2021; 9: 100355.

- Karakas LA, Azemi A, Simsek SY, Huseyin Akilli, Sertac Esin. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction in pregnant women during the COVID-19 Pandemic Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021; 152: 226-230.

- Lorentz MS, Chagas LB, Perez AV, Paulo Antonio da Silva Cassol, Janete Vettorazzi, Jaqueline Neves Lubianca, et al. Correlation between depressive symptoms and sexual dysfunction in postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021; 258: 162-167.

- Effati DF, Jahanfar S, Mohammadi A. The relationship between sexual function and mental health in Iranian pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021; 21: 327.

- Gungor UF, Yasa C, Ates TM, Ipek Evruke, Cansu Isik, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing measures on the sexual functions of women treated for vaginismus (genitopelvic pain/ penetration disorder). Int Urogynecol J. 2021; 32: 1265-1271.

- Güzel A, Döndü A. Changes in sexual functions and habits of healthcare workers during the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional survey study. Ir J Med Sci. 2021 Jun 30:1-9.

- Culha MG, Demir O, Sahin O, Altunrende F. Sexual attitudes of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Impot Res. 2021; 33: 102-109.

- Farah S, Eng Chui L J, Wai Khin L, Wan Shi Tey, Seng Bin Ang, et al. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction in allied health workers: a cross-sectional pilot study in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. BMC Womens Health. 2019; 19: 137.