Gaps in Sexual Assault Prevention in Natural Disasters

- 1. School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mount Royal University, Canada

- 2. Department of Nursing, University of Holy Cross, USA

- 3. School of Nursing, University of British Columbia Okanagan, Canada

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was funded in part by a SSHRC grant through the Centre for Community Disaster Research (CCDR). Thanks to the agencies and professionals who were willing to share their expertise and experience, and to our student research assistant, Chelsey Creller. There are no conflicts of interest for the authors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Carter-Snell C. and Troy A. designed and conducted the research. Carter-Snell, C., Troy, A. and Waters, N. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. Carter-Snell, C had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. There are no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

6. World Health Organization. Violence and disasters. Prevention. 2005: 1-2.

7. Sexual violence in disasters. 2009.

9. Tabellini F. Why does vulnerability to human trafficking increase in disaster situations. Regional office for Central America and the Caribbean. 2020.

29. Brymer M, Jacobs A, Layne C, et al. Psychological First Aid: Field Operations Guide. 2006.

32. SAMHSA-Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Phases of disaster. SAMHSA. 2020.

Abstract

Background: Women’s risks for sexual assault rise significantly during disasters. The potential impact on their health is profound, making prevention or effective early intervention essential. International protocols are available for sexual assault prevention and intervention during disasters, but these have not been observed in North American disaster responses.

Aim: The purpose of this research was to identify sexual assault prevention and intervention practices during natural disasters in Canada and the United States.

Methods: A two-part study was conducted. First, a Canadian environmental scan was conducted with disaster agencies to identify policies or practices used to mitigate sexual assault during disasters. In part two, an exploratory qualitative study was conducted with sexual assault and emergency professionals from North American communities that had experienced natural disasters. Participants were asked about sexual assault prevention and intervention and recommendations. Results were thematically analyzed.

Results: The environmental scan revealed a lack of policies to prevent or respond to sexual assault in disasters. The qualitative interviews showed numerous gaps in awareness and interventions related to sexual assault during their disaster experiences: a lack of awareness of increased risks for assault or effective responses during disasters, lack of collaboration with sexual assault community agencies, lack of prioritization to restore sexual assault services, and limited data collection about assaults.

Clinical implications: Gaps in sexual assault prevention, intervention and data collection are present. These can be aided through awareness and collaboration with sexual assault agencies in planning and responding during natural disasters.

Strengths & limitations: The small number of participants typical of qualitative research limits transferability, but the saturation of themes across settings and the triangulation of data between studies support the trustworthiness of the findings.

Conclusion: There are significant gaps in sexual assault prevention and intervention during North American disasters studied. A discussion of strategies to address gaps is suggested.

Keywords: Sexual assault; Disaster; Gender-based violence; Disaster planning

Citation

Carter-Snell C, Troy A, Waters N (2022) Gaps in Sexual Assault Prevention in Natural Disasters. JSM Sexual Med 6(1): 1079.

INTRODUCTION

Gaps in Sexual Assault Prevention and Intervention during Natural Disasters

Women face disproportionate risks of sexual assault and intimate partner violence compared to men, thus it is termed “gender-based violence” (GBV). Although exact data are difficult to determine, the World Health Organization confirm that rates of GBV are typically higher during disasters [1]. North America is experiencing increasing rates of natural or environmental disasters such as floods, wildfires, tornados and hurricanes [2]. Examples of GBV are available which highlight the risks for women during these disasters. Sexual assault rates were 16 times greater than the national average among those displaced by the Gulf Coast hurricanes [3]. Rates of intimate partner violence, which often include sexual violence, increased as much as 4.5 times greater after those hurricanes, and continued to occur at high rates for at least two years afterward [4]. After the Calgary flood, three times as many clients sought sexual assault care than before the flood [5].

The risks for sexual assault are particularly high in disasters where there are displacements or evacuations, broken social networks, or reduced available services [1]. The people populating emergency shelters typically don’t have family or other networks, and are thus more socially isolated and vulnerable. Relocation takes people away from their familiar services and the disaster may reduce access to any services if they were damaged or shut down. Evacuees may therefore not know what is open, how to access services, or have the means to get there. Additional risks for women include greater levels of financial insecurity or unemployment during the disaster, greater likelihood of remaining behind, and difficulty accessing birth control and feminine hygiene products [6-8]. The women’s increased vulnerabilities and the assailants’ ability to access and control them raise the risk of sexual assault further. For instance, women may be coerced into sex activities to barter for food and supplies, or even into sex trafficking situations [9].

Data on sexual assault are hard to obtain even in non-disaster situations. Repeated Canadian General Social Surveys reveal that only 10% of women report sexual assault to police, although as many as 30% seek health care [10]. Any data on reported sexual assaults are therefore gross underestimates. An additional difficulty is that women may not be recognized as having experienced an assault when they do seek help. They may seek healthcare days, weeks or even years later, often for conditions other than the assault. Consequences of sexual assault include high rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety [11] and physical stress related chronic illnesses such as autoimmune disorders, cancer, disease, diabetes and heart disease [12,13]. As a result, women may show higher rates of health care utilization for years post-assault [14-17], and costs to the community can increase significantly post-assault for years later [13,15,18]. These visits may not be linked to the assault nor are the women asked about prior assault. Even if victims do disclose, confidentiality of health information limits coordination of data, as does determining a suitable period in which to collect the data or link issues to the assault.

The high rates of sexual assault and associated consequences for women highlight the need to mitigate risk in disaster planning and intervention. These high risks and the “exponential” increase in North American natural disasters [2], make it vital that efforts are made to prevent sexual assault or intervene as early and effectively as possible. Early trauma-informed responses by professionals after recent sexual assault have been associated with reduced risks of PTSD and subsequent health consequences [19]. These interventions are typically provided by healthcare personnel who specialize in comprehensive sexual assault care and counselors who specialize in sexual assault recovery. Many also work with that experiencing intimate partner violence, mostly women, so these services are referred to here as GBV agencies or specialists.

Very little research is available in which GBV prevention or effectiveness of interventions is studied in North American disasters. A review of 77 agencies in Canada and the USA in 1999 identified a lack of measures to prevent domestic violence in disasters [20]. Since then, numerous extensive standards and recommendations to prevent or reduce GBV in disasters have been developed both in the USA7 and internationally in collaboration with the United Nations [7,21-25]. These standards give priority to the provision of sexual assault health care and counselling services during and after the disaster, implementation of measures to improve safety against GBV during disasters, and to ensure collaboration in planning between disaster agencies and GBV specialist services to provide continuity of GBV services in various disaster scenarios. All three authors have provided nursing care during disasters and two also have extensive experience working with clients experiencing sexual assault or intimate partner violence. They did not observe implementation of these measures during their experiences in evacuation centres or assigned residences. Women expressed concerns during these events as did the authors, providing the impetus for this study. Investigators wished to determine the nature and extent of GBV prevention or intervention strategies during natural disasters in North America, with a particular focus on sexual assault. The purposes of this two-part study were the following:

• Identify any data related to rates of sexual assault during natural disasters in Canada and the United States,

• Identify provisions in existing disaster plans across Canada to reduce risks for sexual assault during the disaster and immediately post-disaster,

• Describe risk factors for sexual assault identified by GBV agencies who provided services during natural disaster experiences, and

• Determine lessons learned during disasters related to sexual assault prevention and services from eight communities who have experienced natural disasters (four Canadian and four American)

There were two parts to this study. The first was an environmental scan of disaster relief agencies related to sexual assault practices in disaster planning, and a qualitative study of professionals working with either disaster relief or GBV services. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Board of the lead author’s university for both study parts. Ethics measures included strategies to maintain anonymity of participants, thus specific agencies and disaster sites are not identified. Participants were also given an opportunity to view which quotes would be used to ensure they were comfortable and not identifiable.

METHODS

The purpose of the environmental scan was to contact Canadian disaster response agencies at local, provincial, and federal levels to identify presence of existing protocols or practices to reduce sexual assault or other forms of GBV, and any data they had collected on GBV in disasters.

Part 1: Canadian Environmental Scan

Disaster response agencies were eligible to be contacted if they provided either disaster relief or coordinated emergency management operations at the local, provincial or national level in Canada. Representation was sought from all provinces and territories. The agencies were identified through the internet and contacts in the Centre for Community Disaster Research at the university. Following ethics approval by the primary investigator’s university, the agencies were contacted by a research assistant to ask if they had incorporated any policies or practices to prevent GBV in their disaster guidelines, if they would share these, and if they were aware of any data related to rates of GBV in disasters they may have experienced. Data were documented on a spreadsheet and were to be descriptively summarized and quantified.

Part 2: Exploratory North American Qualitative Study

An exploratory qualitative study methodology [26] was then implemented for the second phase. Communities were considered for inclusion if they experienced a natural disaster (e.g., floods, hurricanes, wildfires) which also resulted in some level of evacuation or relocation. A total of eight communities were selected: four in Canada and four in the United States of America (USA). Most sites had experienced their disasters in the last five years. One community evaluated had experienced a hurricane more than 10 years prior, but the magnitude of the disaster and evacuations were such that researchers chose to include the site and learn from the professionals.

A purposive sample of professionals was sought who had worked with either agencies responding to and coordinating the disaster response (e.g., Emergency Management Agencies or disaster relief), or professionals from sexual assault healthcare or counselling agencies. Potential participants within each community were identified through a combination of the contacts used in the environmental scan and a snowball approach, asking each participant for other names of agencies or contacts in their community who may be able to provide information about their disaster experience. They were contacted by email or phone. The study purpose, process and possible interview questions were explained. Although the researchers knew of some of the participants through common conferences and associations, there were no relationships between them.

After obtaining informed consent, semi-structured interviews were conducted via telephone. Canadian interviews were conducted by the primary researcher- a certified sexual assault nurse examiner, educator and PhD prepared researcher in GBV. The American interviews were conducted by the second author, also a sexual assault nurse examiner and advanced practice nurse, researcher and educator. These interviews were scheduled at a time of the participant’s choice, then were recorded and transcribed. The two interviewers listened to each other’s initial interviews and discussed probing questions and standard approaches. Participants were asked the following initial questions with subsequent probes, as appropriate:

• Strategies in place for sexual violence prevention in the immediate aftermath of the natural disaster,

• Provisions to protect women and children in evacuation centres from sexual violence,

• Services in place for women and children who experience sexual violence during the natural disaster or its’ aftermath, and

• Barriers for sexual violence prevention or early intervention post-disaster?

During the interview the researchers kept field notes. These were kept in a shared password protected folder online. Thematic analysis was used with the transcripts of the interviews, deriving codes and themes from the data [27]. NVivo version 12 was used to store and code the data. The primary investigator conducted all initial analyses, starting with an open vertical analysis of each transcript, and coding of key terms. Horizontal analysis was then conducted between transcripts to look for common terms and themes. This process was repeated each time an interview was conducted. A codebook was maintained for auditability. These themes were discussed with the second investigator and discussed to ensure consensus. Both investigators were sexual assault specialists and had disaster nursing experience, thus contributing to credibility of the interpretations. Unmarked versions of the transcripts were given to the third investigator for open review, followed by the coding tree and codebook. The third reviewer was also experienced with disaster nursing as well as qualitative research methods, supporting both credibility and dependability of the themes.

RESULTS

Part 1: Environmental Scan

A total of 23 Canadian emergency management agencies (municipal, provincial, and federal) and disaster relief agencies were identified. Attempts were made to contact all between fall 2017 and spring 2018. Only nine of these agencies had personnel who responded or were able to provide information, but some of these respondents were responsible for coordinating disaster relief or emergency management operations in multiple provinces and jurisdictions.

None of the agencies had policies or protocols that incorporated recognized GBV guidelines into their response, and none had data collected on GBV. Most of those interviewed considered separating women and children from the main population, or had grouped communities together to “self-regulate”, but these were fluid responses which changed from situation to situation. Only one of the respondents, representing a national relief agency, had implemented any safety measures. They had instituted a Safety and Wellness branch into their disaster response, but the focus was on general safety and wellness rather than on risks specific to GBV.

Part 2: Qualitative Study

Ten professionals responded to the requests to be interviewed and agreed to be interviewed in 2018 (Table 1). None refused and each was interviewed once for approximately 45 to 60 minutes. The participants represented a total of 9 disaster regions. Each of the Canadian participants represented agencies involved in more than one disaster and community and were able to give a broad perspective. Some were involved in province-wide or multiprovincial responses so there was overlap between some of the participants’ experiences and communities. All communities in both the USA and Canada experienced at least partial evacuation of residents, a circumstance known to increase GBV risks (Table 1).

| Location | Type of Disasters (n) | Professional Participants (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Canada |

Floods (2) Wildfires (2) Tornado (1) |

Emergency management agencies/disaster relief (3) Sexual assault counsellor (1) |

| USA |

Flood (2) Tornado (1) Hurricane (1) |

Sexual assault healthcare (4) Emergency management agencies/disaster relief (2) |

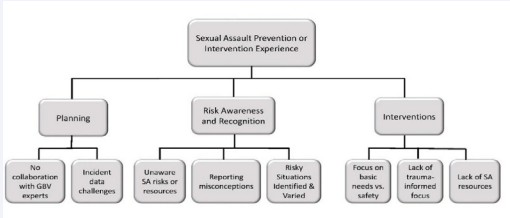

Several key themes were identified in the data as shown in Figure 1. Overlapping information was obtained from the participants in the themes identified; supporting saturation of themes and that sufficient data were collected. Interviews were thus concluded with the 10 participants. Although all participants were emailed with the opportunity to review their data, none chose that option. Credibility was therefore obtained through consensus with the two sexual assault examiners, and dependability with the review and consensus of all three authors.

Figure 1: Themes and Gaps in Sexual Assault Disaster Responses.

Lack of Collaboration

None of the participants identified collaboration with GBV focused agencies (e.g., women’s shelters, counselling, or sexual assault healthcare response teams) in disaster planning or in their responses. In fact, one participant described counsellors from the sexual assault centre going to the evacuation centres but only for their general counselling knowledge, not GBV services or support. There was general recognition that there was a need to collaborate- “…. [we] recognized the need to have more support between the two neighboring communities”. One participant described a successful collaboration for child safety in their relief response and added “We need to consider what similar collaborations can occur for gender safety- there are sexual assault prevention needs in other areas as well”.

Incident Data Challenges

Gaps were identified in data collection and data sharing amongst the services who responded to the natural disasters. One service agency professional said “After the disaster our per capita cases increased and did for several years” but the disaster agencies were unaware of this. “If a client went to the…. health services individuals, we probably would not even hear about it”.

| Phase | Gap Identified | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Disaster |

• Unaware of GBV risks in disaster • Lack of collaboration with GBV specialists • Lack of trauma-informed focus |

• Collaboration with GBV agencies • Have SA personnel provide training on SA risks and safety concerns • Implement trauma-informed training and prepare staff for appropriate responses and referrals • Plan data collection, indicators, and sources • Discuss processes and options for providing SA healthcare and support |

| During Disaster |

• Risky situations present and variable by centre • Focus on basic needs-not SA Lack of SA resources • Reporting misconceptions |

• Conduct risk assessments and safety audits • Implement SA specific safety measures • Ensure SA health services and counselling available • Communicate access and SA services available to public and evacuees • Begin/maintain data collection and collaboration |

| Post-Disaster |

• Incident data challenges • Lack of SA resources |

• Prioritize maintenance and/or re-opening of SA services and communication • Continue support for women in high-risk areas • Continue data collection up to 2-3 years • Conduct a review of SA prevention and intervention effectiveness |

Risk Awareness and Recognition

Unaware of GBV Risks or Resources: There was general surprise that GBV rates increased during natural disasters and that there were guidelines for GBV prevention in disasters. Almost all participants expressed they were unaware, including those in emergency management agencies and professionals who worked in sexual assault centres. One participant said, “I was very embarrassed because I had worked in domestic violence and sexual assault for years and it never crossed my mind in a disaster response operation”. Other comments included “general surprise that the sexual assaults still occurred, even during a disaster” and “I had not even thought about the potential for sexual assault or violence in the shelter until [name of disaster]”. They were unaware there were international guidelines for sexual and reproductive health in disasters but were interested, and typically asked to learn or to have resources sent following the interviews. As an example, one of the agencies asked for follow up training of their personnel post-study. They made immediate efforts to include recommended GBV reduction strategies into their protocols although, to our knowledge, they still do not liaise or plan with the GBV specialists in the region. Since the study was conducted, other communities have created offices of Gender Equity which are being included in disaster planning.

Reporting Misconceptions: Questions were asked about what they did or planned if a sexual assault occurred, such as letting evacuees know where to go, what services were open or where to report the assault during the disaster. No one had any plans for these instances and most indicated a mistaken belief that victims would notify security or staff. “If something does occur at a special needs shelter, if there is an incident, the process that our department has, there would be a report that would be filed and how to prevent it in the future and to address the issue”. “There are police officers and…Health Services-maybe not that particular specialty on site”. They were not aware that even in non-disaster settings that very few women report their assaults, nor that they may have difficulty knowing where services are or may have issues traveling to the services.

Risks Present and Vary: Most recognized that during their disaster experience there were potential situations that created risks for sexual assault. “It [sexual assault] is a crime of power and control and whenever someone is more vulnerable, they are going to be at greater risk for sexual assault.”. “The last thing people want to think about is sexual assault-that makes it easy for someone to commit sexual assault”. Another said, “If people are displaced and are living in congregate settings, maybe even tent communities, which could affect safety”. An additional finding was related to risk based on the type of evacuation centres used. Some described they likely had a high risk of sexual assault in the large arena style evacuation centres as well as women or children not feeling safe at the time. Some described post-disaster reports of sexual assaults but had no data. Although it was anticipated that private accommodations such as student residences or hotels may be safer, it was found that hotel or residence accommodations were also potentially high risk. One participant described a large mass evacuation of an entire community to a hotel in another city. There were numerous sexual assault risks identified by the teams, including finding sex traffickers trying to gain access to teens placed in rooms on their own, difficulty supervising or being aware of risks behind closed doors, and introduction of some of the youth to drugs and alcohol which increased their vulnerability to sexual assault. One participant also described “situations where restraining and no contact orders were breached in the hotels”. This was exacerbated by assigning family members together if they had the same name. Staff were unaware of the existence of restraining orders against family members or risks for intimate partner violence. This placed the women at further risk of sexual assault and other forms of violence. Similar to the participants in the environmental scan, they described risks as changing with the situation and appropriate accommodations having to be determined disaster to disaster.

Interventions

Focus on Basic Needs: Understandably, participants described a focus during their disaster experience on food, security, shelter, and general safety, but this was perhaps to the exclusion of recognition of GBV risks. The emphasis was typically more on protecting evacuees from outside dangers versus risks within the centres. One participant stated he was “...more worried about the bear outside the door” than anything occurring within the shelter. This was in part due to potential vulnerability of the relocated population. “People that end up in our facilities tend to be more vulnerable without those social connections” and the workers’ restricted access to the clients. Others indicated they did not think anyone would consider assaulting others when resources were so scarce. “The people who are trying to put one foot in front of the other-I don’t think it’s even crossed a lot of people’s minds”. “Justice isn’t always at the forefront of their mind”. General measures to ensure safety of the population were described by all, including safety teams with one Canadian interviewee, but none described having any safety measures specific to prevention of sexual assault violence such as those recommended in the international guidelines. A few indicated they were aware of risk within the populations. “We were aware that we had vulnerable populations intermixed but tried to take mitigation actions to protect that”. “There was definitely scope for sexual assaults to happen in perimeter areas, however having security walk around was helpful to minimize that”. “We tried to get women and young children into hotels right away but there were protection issues within the hotel-in some ways it was safer in the shelter than it was in the hotel”.

Lack of a Trauma-Informed Focus: A trauma-informed focus is based on four major assumptions: realization of risks and consequences, recognition of trauma responses, interventions appropriate for trauma responses, and resisting retraumatization [28]. There was both a lack of awareness of risks as previously described, and of the characteristic responses and consequences of sexual assault on individuals and communities. One example was the expectation that women would report the sexual assault to security in the centres. This knowledge gap resulted in participants asking for information post-interview. As the interviews progressed, the GBV professionals recognized the disaster responses had not been trauma-informed and that this approach was not part of the typical training for first responders or disaster planners. The professionals familiar with sexual assault services emphasized the need for a trauma informed focus in the disaster response in future. “I think the crisis centres would be the primary entity because the staff have been trained to be victim advocates in that regard”. There was some frustration expressed by one sexual assault nurse who was redeployed for her general nursing skills, rather than for her sexual assault knowledge or skills. “Are you going to send someone on a raft or boat to come down? Or will you send a nurse who is used to dealing with these kinds of patients in a trauma setting? It’s trauma-informed care versus patient informed”. If evacuees had disclosed a sexual assault, the professionals involved would not necessarily be aware of how to initially respond or how to avoid re-traumatizing those in need before helping them access services.

Lack of Sexual Assault Resources during and After Disaster: Professionals described sexual assault services being shut down or moved during the disaster or staff being used for other purposes. “The sexual assault centres put everything else on hold and all resources are put towards the evacuation sites”. “During the disaster, from what I understand, there were sexual assaults happening but nowhere to have them seen here, so they had to be sent to other places, to another city, because we don’t have any services here right now”. “It took three and a half months- the services we were offering were the same services although they were in a completely different environment after. When we got back into a building that had an actual centre, I would say a year and a few months”. “The whole financial system was shut down -they didn’t have the resources”. Some services in one American site remained shut down for many years postdisaster.

A limitation of the research is the small number of participants representing each of the disaster services in both the scan and the qualitative study. The saturation of themes in the qualitative study, however, supported a sufficient sample size. A further strength was that the data from both the environmental scan and the qualitative study were consistent. This increases confidence in the findings, combined with efforts to increase credibility and dependability with the review of data and themes by all three reviewers, and was consistent with the experiences of the researchers during natural disasters.

DISCUSSION

The results of this two-part study highlight some significant gaps in sexual assault prevention and responses. These gaps include limited knowledge of sexual assault risks and international guidelines for prevention and intervention which could be used in emergency management planning. A collaborative approach would be especially helpful in which health professionals who provide acute sexual assault services, as well as sexual assault counsellors are included in the emergency management planning before disasters. These gaps are of concern when it is the emergency management and relief agencies planning access, interventions and mobilizing human resources for disaster responses. Although some teams have social workers on their disaster planning, not all have in-depth familiarity with sexual assault or knowledge of the agencies affiliated with services in the community. The sexual assault services professionals can be used in non-disaster times to provide trauma-informed training identify key services to maintain if a disaster occurs, and identify alternatives if sites are closed and develop communication systems to support data collection and integration between agencies during or post-disaster. The trauma-informed training would include information to address the risks and consequences faced after sexual assault, and to facilitate recognition of the signs of trauma responses and how to respond appropriately without causing further re-victimization for those in need waiting to access specialized services. Sexual assault agencies can assist by identifying their services as essential, to limit redeployment of experts and ensure continued services.

The need for collaboration with sexual assault experts is further supported by disaster planners becoming familiar with international guidelines for prevention and intervention with sexual assault and intimate partner violence in disasters. During the disaster, while safety measures are needed to prevent unnecessary access to evacuees from outside, there is also a need to introduce sexual assault safety measures within the sites. Recognition that most victims will not report to police or security and alternate measures should be in place to inform evacuees what to do or where to go if an assault does occur. The decision of where to send evacuees should include weighing risks of sexual assault or intimate partner violence with the circumstances. These considerations will be unique to each disaster and the number of evacuees affected but can be assisted with consultation and continued collaboration with sexual assault providers.

There are numerous clinical implications for these findings. Although a comprehensive description of the interventions and guidelines is beyond the scope of this article, a generic set of recommendations is proposed in Table 2 to address the gaps identified. These recommendations are consistent with core principles in the expert consensus guidelines [21-23] and the USA guidelines [7]. These guidelines are also applicable for other types of disasters or pandemics.

In the pre-disaster phase those providing GBV services should actively seek collaboration with emergency management and disaster relief agencies. There should be an emphasis on identifying vulnerabilities, risks, and resources in the community [23]. Representatives from marginalized populations at risk should also be considered for inclusion in planning. The GBV specialists can provide training to the disaster agencies which, at a minimum, should include psychological first aid [28,29], as well as trauma informed training [28] to minimize further harm and promote recovery. This training would better inform decisions such as the importance of keeping sexual assault or domestic violence services open, the need to make clients aware of how to access these services in unfamiliar shelters, and how to provide sexual assault support if a disclosure is made. Emergency protocols should be reviewed to ensure they include international guidelines to mitigate GBV. Research is needed to evaluate effectiveness of various prevention efforts and to support the need for funding GBV services in disaster [30]. A collaborative approach between agencies and sectors will help identify key indicators and sources of data. Agencies will have access to data and trends that would otherwise not be available to disaster agencies. GBV agencies and healthcare services typically see women days, months or sometimes years after the sexual assault and lack of collaboration would not allow linkage of these assaults with the disaster. This collaboration could also help facilitate preparation of plans to obtain emergency human ethics research approvals in anticipation of disasters and the need for data collection from those affected. Disaster agencies should also consider research priorities, potential collaborators with research experience, and mechanisms to mobilize and conduct relevant research on sexual assault if a disaster occurs.

During the disaster, the sexual assault specific safety audits and risk assessments should be conducted and GBV safety measures implemented. Examples include distribution of dignity kits with menstrual products and contraception, safe areas for women and children, and provision of or easy access to sexual assault and intimate partner violence health and counselling services. Risks for GBV vary in each disaster- large arenas, residences and hotels can all have their own forms of danger, as can isolation in one’s own home. Collaboration with GBV experts may help identify these unique risks on site and support provision of trauma-informed services throughout the response. The risks found with relocating communities highlights a wellknown understanding in disaster response- the problems the community had before the disaster move with the community. An understanding of the community is required prior to initiation of collaboration between agencies to increase awareness of risks such as no contact or restraining orders. The GBV services and personnel available also change with circumstances and each disaster. There should be clear messages for evacuees and the public in general about where to go or how to seek GBV help during or after the disaster. Transportation arrangements may be needed as well, such as taxi vouchers or bus passes if women must leave the site. Ideally services are within the same community as the evacuation centre, as taking victims out of their community, removing them from support people or making them wait for long periods can be retraumatizing and increase their risk for consequences such as PTSD [31]. Conversely, receiving early effective services can reduce the risks of PTSD [19], and potentially prevent long term health issues for individuals or the community.

After the disaster resolves, there is still a need for GBV services, for months or years after the disaster due to the potential long-term effects. Priority should be given to keeping GBV healthcare and counselling agencies open or reopening them as soon as possible. If residents are evacuated out of their community, there should be efforts made to send counselors and health experts into the centres or communities to make it easy for clients to connect with them. Clients are unlikely to report to police or shelter staff and are more likely to seek healthcare or counselling- they see justice and healing as separate processes. GBV risk reduction may also need to be extended-women left in high-risk areas or housing need improved security and ongoing food and shelter support until communities are rebuilt. Data collection efforts also need to continue. Typically, an individual’s disaster response continues for at least two to three years after the initial impact [32]. Once the crisis is relatively resolved, the Emergency management agencies should conduct a review of GBV risks, services and data to identify areas for improvement and risk reduction for future disaster responses.

CONCLUSION

Despite evidence of increased risks for sexual assault during disasters, significant gaps were found in sexual assault prevention and interventions among those interviewed after experiencing disasters in their region. There was, however, widespread interest in learning about the guidelines and collaborating. There are opportunities for those providing sexual assault services to form collaborative relationships to aid prevention and intervention during disasters and to integrate the international guidelines. These efforts will potentially prevent assaults and contribute to improving the health and resilience of the community postdisaster.