Health Care Professionals

- 1. Medicine graduate at Rey Juan Carlos University, Spain

- 2. Pediatrician at University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón, Spain

- 3. Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Universitary Hospital Fundación Alcorcón, Spain

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Intimate partner violence has become into a public health issue. This study was carried out in Primary Care Centres and its main objective is to investigate healthcare professionals’ degree of awareness on IPV.

Design and Methods: Cross-sectional descriptive study with a validated, anonymous, self-administered questionnaire was carried out. Data was analysed using SPSS 26.

Findings: The response rate was 12.7%. 49.6% of the healthcare professionals were aware of IPV and 68.3% detected it at work. 48% received training and 94.8% believed that it is a serious problem. Practical implications: Healthcare professionals are more aware and less influenced by stereotypes, but they lack time, space, and specific training to care for victims.

KEYWORDS

Intimate partner violence, Domestic violence, Primary care, Emergency medicine.

CITATION

González BL, Baranda AG, Arredondo Provecho AB (2022) Health Care Professionals’ Perspective on Intimate Partner Violence against Women. JSM Sexual Med 6(6): 1103.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organisation defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm to women, including threats, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life’’ [1]. It is the most widespread and perpetuated human rights violation as a form of discrimination against women. The most frequent form of violence is intimate partner violence (IPV). 1.8% of women over the age of 16 living in Spain have suffered physical and/or sexual violence and 10.8% have suffered some form of intimate partner violence in the last year. The mortality figures are much more alarming: between 2003 and 2022, 1134 women have been murdered in Spain and in the year 2022, as of 12 May, there are already 14 victims killed by their partner or ex-partner [2].

Violence against women is a problem that affects the whole community and is therefore considered a public health problem [3]. It not only involves greater morbidity due to physical injuries, but also psychological consequences, greater substance use, higher rates of absenteeism from work, disability, poorer perception of health status and more thoughts of suicide. This means that they are patients who come to the health services more often and makes health professionals potential early detection agents. 41.9% of women who have suffered physical or sexual violence have visited an emergency department in the last year [4]. However, very few women are asked directly if they suffer or have suffered intimate partner violence [5], so that the request for help is fundamentally based on their own will.

IPV does not only affect the women, but it also has an impact on the children living in the household where the violence takes place. 54.1% of the victims of any partner had children at the time of the violence and they heard and/or witnessed the violence; 89.6% were minors [4]. Witnessing violence against women has been linked in extensive studies on Adverse Childhood Experiences to poorer overall health and an increased risk of problems affecting the physical, cognitive, socio-emotional and academic spheres [6-10]. Therefore they should be considered in cases of suspected IPV and referred to the appropriate services [11].

Several studies conducted at the University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón (HUFA) and Primary Care show difficulties in the early detection of IPV cases due to organisational barriers such as lack of time, fear of reprisals and lack of institutional support. Health professionals have an average level of knowledge, are becoming increasingly aware and consider IPV very or fairly important problem. However, in 2016, 79.8% of the professionals surveyed at HUFA had not received training and considered it essential to know how to act appropriately [12,13].

The main objective of the study is to research the degree of awareness of professionals about IPV. The secondary objectives are to analyse the level of knowledge and level of training of professionals on IPV, to identify attitude and organisational barriers to action, to analyse opinions and proposals for improvement for early detection, to describe the demographic characteristics of the respondents and to analyse differences in the level of knowledge between services.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted using a validated, anonymous, self-administered questionnaire modified from the one used in the study by Arredondo Provecho, et al. Partner violence against women and specialised care health professionals [14]..It was distributed between 15 December 2021 and 20 March 2022 via institutional mail through an access link available to the entire multidisciplinary team, understood as any professional, both health and non-health professionals, working in the HUFA, “Laín Entralgo” and “Los Castillos” Health Centres and the out-of-hospital service in the area, SUMMA 112. All responses from professionals who did not meet these criteria or who came from other communities were excluded. A total population of 1,984 professionals was estimated (HUFA: 1,750 professionals; “Laín Entralgo” HC: 43 professionals; “Los Castillos” HC: 46 professionals; SUMMA 112: 145 professionals).

Ethical-legal aspects

The study has the approval of the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón under number 2138 and dated 2 December 2021, the Research Commission of SUMMA 112 and the West Local Research Commission of Primary Care.

Variables

The modified survey consists of 35 questions (Annex) that takes approximately 5 minutes to complete. The first 26 questions assess the main objectives of the study, followed by 6 questions on demographics and two on IPV training. The first 26 questions can be analysed in three distinct groups:

a) Level of knowledge of professionals about IPV. It begins with 4 questions on case detection, action and knowledge of available resources (1-4). It continues with a knowledge test of 10 questions (5-11 and 14-16). These are closed questions with a choice of two or more options and two open questions (5 and 8). The level of knowledge is established according to the correct answers out of 10 in: very low (less than or equal to 2), low (3-4), medium (4-6), high (6-8) and very high (greater than 8).

b) Opinions and attitudinal barriers. Opinions (12,13, 17, 21-23) and action guidelines (18-20) are assessed through closed questions to choose from several answers. In addition, are assessed the roles of health workers and ways of raising awareness among colleagues (24 and 25).

c) Organisational barriers and proposals for improvement. Two open questions are offered in which ideas can be proposed (26 and 27).

To accommodate out-of-hospital emergency services, the categories “Emergency medical technician” and “Out-of-hospital emergency” were added in questions 27 and 28. In addition, a section has been added to identify the service to which respondents belong and the autonomous community (29) and two questions on the detection of underage or secondary victims of IPV (20).

Statistical analysis

Data were collected in an Excel document associated with the survey’s computer platform (Google Forms) and analysed using STATA 16. Qualitative variables are described in terms of absolute and relative frequencies. Quantitative variables are described in terms of mean, standard deviation, quartiles, minimum and maximum value. The Chi2 test was used to compare responses according to the professional category variable and the MannWhitney U test was used to compare the level of knowledge (according to score). Open-ended questions are grouped by equivalent proposals or opinions put forward by professionals and are described in terms of relative frequencies.

RESULTS

The survey was distributed to 1,984 professionals from the University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón, the “Laín Entralgo” and “Los Castillos” health centres and SUMMA 112. It was sent via institutional mail, the hospital’s Violence Commission and two referring doctors from the health centres. The response rate was 12.7%. A total of 252 professionals from different fields replied, mainly doctors (45.2%), nurses (28%) and emergency medical technicians (E.M.T.) (9.2%). In terms of workplace, they worked in specialised care (42.4%), SUMMA 112 (28.6%), primary care (12.2%), emergency (8%), administration (6.7%) and laboratory (2.1%).

In terms of socio-demographic variables, 71.4% of the respondents were women and 26.2% were men. There were statistically significant differences in the distribution of professional categories by gender, with most nurses being female (34.3% women and 12.1% men), most E.M. T.s being male (30.3% men and 1.1% women) and doctors being equitable (45.5% women and 43.9% men). The average age of the respondents was 46.39 years, and the average professional experience was 20.13 years. The data are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Socio-demographic data of the professionals tha completed the survey.

|

Gender |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Women |

180 |

71.40% |

|

|

Men |

66 |

26.20% |

|

|

Other |

6 |

2.40% |

|

|

Marital Status |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Married |

130 |

51.60% |

|

|

Single |

83 |

32.90% |

|

|

Separated/Divorced |

29 |

11.50% |

|

|

Widower |

4 |

1.60% |

|

|

Professional Category |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Doctor |

113 |

45.20% |

|

|

Nurse |

70 |

28.00% |

|

|

E.M.T |

23 |

9.20% |

|

|

Administrative Staff |

15 |

6.00% |

|

|

Nursing assistant |

13 |

5.20% |

|

|

Categoría profesional |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Warden |

7 |

2.80% |

|

|

Manager |

3 |

1.20% |

|

|

Lab Technician |

3 |

1.20% |

|

|

Social Worker |

2 |

0.80% |

|

|

Occupational Therapist |

1 |

0.40% |

|

|

|

Age |

Professional Experience (years) |

Training (hours) |

|

Mean |

46.39 |

20.13 |

44.28 |

|

SD |

11.34 |

11.039 |

141.9 |

|

Min |

22 |

0 |

2 |

|

Max |

69 |

45 |

1500 |

|

p25 |

39 |

11 |

8 |

|

p50 |

47 |

20.5 |

20 |

|

p75 |

55 |

29 |

40 |

CASES AND ACTION

49.6% knew of a case of IPV in their environment and 68.3% had detected a case in the course of their work. In the last three months they detected a mean of 1.10 cases with a standard deviation of 2.75. Of those who saw a case in the course of their work, 51% detected between one and five cases (22% detected between 1-2 cases, 17% between 2-3 cases, 9% between 3-4 cases, 2% between 4-5 cases), 2% between 5 and 10 cases and only 4% detected more than 10 cases. The group that detected the highest proportion of cases was the E.M.T.s. (95.7% detected on some occasion) followed by doctors (73.5%) and nurses (68.6%), with the rest of the categories detecting the least (43.2%), demonstrating statistically significant differences (p = .000).

Attitudes towards detecting a case of IPV were to initiate an abuse protocol (27.3%), fill in an injury report (26.2%), refer to another professional (37.8%) or do nothing (12.8%). The justifications for not acting on a case of IPV were lack of training (36.8%), not considering it their competence (15.8%) and due to the patient’s refusal, fear of being called or questioned or considering it difficult to prove (10.5%).

TRAINING AND LEVEL OF KNOWLEDGE

The mean of knowledge was 5.32 points with a standard deviation of 1.83. Specialised care and SUMMA 112 workers scored above the mean (6 and 5.5 points respectively) and doctors and nurses also scored one point above the mean (6 points) compared to E.M.T.s and other professional categories, although no significant differences were found.

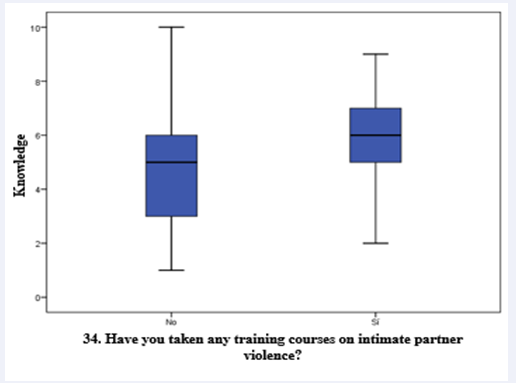

48% of the professionals had been trained on IPV. The median number of hours of training was 20 hours with an interquartile range of 8-40 hours. Being more trained had a positive impact on the level of knowledge: the trained professionals scored one point higher than the untrained (6 points vs. 5 points); statistically significant differences were found (p = .000) as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Comparison between training and level of knowledge.

There are also significant differences in training between services (p = .000), the most trained service was SUMMA 112 (44.5% of those who had received training); and between professional categories (p = .000), the least trained group was that of doctors (51.6% of those who had not received training).

Among the most missed questions, 38.9% thought that IPV is associated with low social classes and that the main factor for violence to occur is belonging to a low socio-economic or sociocultural class (44.4% of respondents). 96% consider that most cases go unnoticed but 82.1% do not know the percentage of undiagnosed cases and 71.45% do not know how to rank the types of violence in relation to their frequency. In terms of legal issues, 54.4% were unaware of the legal repercussions of not reporting an obvious case of IPV, while 63.1% were aware of the legal obligations of health workers in the event of a suspected case of IPV.

85.2% know that there is an action protocol for the health care of patients who are victims of IPV. However, 55.9% are not aware of it. There is a positive relationship between knowing the protocol and detecting cases and initiating it. Of those who are aware of the protocol, 79.8% have detected a case of IPV at some time (compared to 58.3%) with a significant difference (p = .000) and 44.6% have initiated a case (compared to 7.8%) with a significant difference (p = .000).

OPINIONS

Most professionals consider that women who experience IPV are most often any type of woman (78.5%) and the abuser is usually a man like any other (85.7%). However, there are still stereotypes among professionals: they believe that the victims are usually uneducated women (10.8%), housewives (6%) or foreigners (4.8%); and that the abuser is usually a male drinker (10.8%), drug user (2.8%) or unemployed (0.8%).

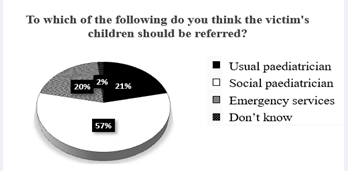

There is some consensus on the importance of the problem of IPV: 94.8% of the professionals believe that it is a very or fairly important problem. However, 20.1% do not usually take a waitand-see approach to the diagnosis of these cases in their routine practice. 16% do not consider as a differential diagnosis that a woman with physical lesions is a case of IPV and only 3.6% do not consider the possibility that their children may also be victims. A total of 57.1% agreed that they should be referred to the social paediatric services (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Services to which professionals think children of IPV victims should be referred.

Up to 96.4% of professionals believe that identifying cases of IPV and solving this problem is a matter for everyone (police, judges, social workers, and health workers). Only 1.2% believe that it is a matter exclusively for the police or judges. Regarding under-detection, the majority believe that it is a problem of the system, 71.5% believe that it is necessary to continue improving detection systems and coordination between the different levels and professionals involved. However, a part of the professionals believe that it is a problem of the victim. This is in line with the opinion of 50% of respondents that there is no consensus on the actions of all professionals involved in the care of female victims of IPV. The opinions and knowledge are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Knowledge and opinions of health professionals about IPV.

|

CORRECT ANSWERS |

Total |

||

|

5. There are differences in the meaning of "IPV", "abuse" and "gender-based violence". |

96 |

38.1% |

|

|

6. HPV in our society is a major or very major problem. |

192 |

76.2% |

|

|

7. Most patients who suffer from it go unnoticed. |

242 |

96% |

|

|

8. They know what the "Iceberg" phenomenon in IPV is |

156 |

61.9% |

|

|

9. They know the percentage of cases that go undiagnosed. |

45 |

17.9% |

|

|

10. They correctly order the types of violence according to their frequency. |

72 |

28.6% |

|

|

11. They associate IPV with high and low social classes equally. |

154 |

61.1% |

|

|

12. The most influential factor in IPV is being in the process of separation or divorce. |

112 |

44.4% |

|

|

15. They are aware of the legal repercussions of not reporting an obvious case of IPV. |

115 |

45.6% |

|

|

16. They are aware of the legal obligations of health care providers in the event of suspected IPV. |

159 |

63.1% |

|

|

Total of right answers |

1343 |

53% |

|

|

Level of knowledge |

Average |

||

|

OPINIONS |

Total |

||

|

12. Women who suffer are… |

Any type of woman |

197 |

78.5% |

|

13. The abuser is a man… |

"Just like any other man". |

215 |

85.7% |

|

17. IPV is a… |

very important problem |

208 |

82.5% |

|

21. There is consensus on participation |

Usually NOT |

124 |

49.8% |

|

22. It is a matter of... |

All |

243 |

96.4% |

|

A. I think that patients suffering from intimate partner violence should be more insistent, have a stronger stance and ask for more help from society. |

6 |

2.4% |

|

|

B. I think it is necessary to continue to improve detection systems and coordination between the different levels and professionals involved. |

178 |

71.5% |

|

|

C. These patients think that their problem has no solution, and that society does not support them. I think they need to change this misconception and should realise the possibilities that exist. |

22 |

8.8% |

|

|

D. I think that patients suffering from partner violence do not yet have the necessary facilities and need more help. |

43 |

17.3% |

|

FUNCTIONS, AWARENESS, AND ORGANISATIONAL PROBLEMS

Detection, accompaniment, referral, and application of protocols are considered by 30.7% to be the main competence of health professionals in tackling this problem, 25.9% consider identification and early detection, 15.3% consider notification of the authorities exclusively and 12.7% consider care, help and protection of the victim. In order to raise awareness, professionals consider that it is necessary to raise awareness, get training and know the protocols and resources for help (32.9%) and empathise, as it could happen to anyone (21.7%).

52% consider that there are organisational or structural problems that prevent these cases from being detected: lack of time and/or training (27%), lack of awareness and/or communication (10%) and work overload (7%). As proposals to improve these problems, they consider it essential to raise awareness through specific training and easily applicable protocols (47.4%) and to have more time per patient and a specific circuit for victims that preserves their privacy (31.6%). These are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3: Functions, awareness, organisational problems and proposals for improvement.

|

24. What do you think are the main roles of hospital professionals in this problem? |

Total |

|

|

Detection, support, referral and application of protocols |

58 |

30.7% |

|

Identification and early detection |

49 |

25.9% |

|

Non responder |

63 |

25.0% |

|

Notification to authorities |

29 |

15.3% |

|

Attention, assistance and protection |

24 |

12.7% |

|

Guidance and information on resources |

12 |

6.3% |

|

Sensitisation, information and awareness raising |

10 |

5.3% |

|

Coordination with the whole team |

7 |

3.7% |

|

25. If you wanted to change the behaviour of health workers by increasing their awareness, with which 3 reasons would you do it? |

Total |

|

|

Non responder |

100 |

39.7% |

|

It is necessary to raise awareness, get trained and know the protocols and resources for help. |

50 |

32.9% |

|

It is everyone's problem, it can happen to anyone. |

33 |

21.7% |

|

We are agents of early detection, we have a relationship of trust with patients. If we are alert, we can be the help they need to get out of this situation. |

24 |

15.8% |

|

It is a health problem with short and long term consequences, not only for the victims, but also for their social environment (children, relatives...). |

23 |

15.1% |

|

It is our moral, legal and social duty to be part of the chain that detects and tackles this problem. |

22 |

14.5% |

|

26. Why do you think there are organisational or structural problems in your work that prevent you from diagnosing these cases? |

Total |

|

|

No problems |

97 |

55.7% |

|

Non responders |

78 |

31.0% |

|

Lack of time and/or training |

42 |

24.1% |

|

Lack of awareness and/or communication |

16 |

9.2% |

|

Work overload |

11 |

6.3% |

|

Lack of 24h care by social worker |

5 |

2.9% |

|

Multifactorial |

3 |

1.7% |

|

27. If you could change the functional organisation of your workplace, what would you do or change to improve the capacity to detect women who suffer intimate partner violence? |

Total |

|

|

Promote awareness through specific training and protocols that are easy to apply. |

64 |

47.4% |

|

Non responders |

118 |

46.8% |

|

More time per patient and a specific circuit for victims that preserves their privacy. |

42 |

31.6% |

|

Increase professional coverage for victims from the first moment (social work, psychologists, etc.). |

13 |

9.8% |

|

Establish multidisciplinary joint action groups |

9 |

3.6% |

|

I would not change anything |

4 |

3.0% |

|

It is a problem that is difficult to solve |

2 |

1.5% |

DISCUSSION

The response rate was lower than in similar studies conducted at HUFA recently (21.4% and 15%) [12,13]. Female representation exceeded male representation (71% female), although it was lower than in previous studies (81.5% and 86.2%), which may denote a small but slow awareness among men.

Although almost all respondents consider IPV a very or fairly important problem, one fifth do not take a wait-and-see attitude to detect these cases in their routine clinical practice and 16% do not consider IPV as a differential diagnosis in the case of a woman with physical lesions. Health professionals are agents of early detection, with 68.3% having detected a case in the course of their work and the average number of cases they have seen in the last three months being 1.1. However, 96% believe that most cases go unnoticed, although most of them do not know how to indicate the percentage of undiagnosed cases and do not know how to classify the types of violence. This denotes a lack of knowledge of the process of violence that prevents an expectant attitude towards the first phase of violence, psychological violence, and early detection in the most prevalent phase.

Professionals have received almost 20% more training than in previous studies, although half of them still have not received training [12,13]. They themselves consider it important for improving detection and this is reflected in the results: being trained not only promotes a better level of knowledge, but also the consideration of IPV as a problem of great importance, detecting a greater proportion and initiating more of the protocol. There are three guidelines for primary care, specialised care and emergency care [14], which need to be made known to the professionals involved since, although most of them know they exist, less than half are aware of them. It would be useful to look at the training of SUMMA 112, which is the service with the most training and the highest level of knowledge, to detect the reasons why the E.M.T.s, despite being more trained and detecting in greater proportion, do not have better results.

Likewise, professionals are more sensitised. There is a consensus about the characteristics of the victim and the abuser: both are people like any other. However, there is an important class stereotype, which has diminished very little since the previous studies: one in ten professionals believe that the victim is an uneducated woman and the abuser is a male drinker, and more than a third of those surveyed consider that violence is associated with, and has as its main promoting factor, belonging to low socio-economic and socio-cultural classes. Regarding children, most of them consider them to be possible victims when cases of IPV are detected, although only slightly more than half of them would know where to refer them. It is important to raise awareness of the figure of the Social Paediatrician as a specific health worker who looks after their biopsychosocial health.

The competences of health professionals that they consider essential to tackle this problem are detection, accompaniment, referral and application of protocols and early identification and detection. This contrasts with the fact that six out of ten are aware of the legal obligations of health professionals when faced with a case of IPV, but more than half are unaware of the legal repercussions of not declaring an obvious case.

The professionals continue to encounter structural problems that prevent the detection of these cases, such as: lack of time and/or training, lack of awareness and/or communication and work overload. The proposals to tackle these problems were to raise awareness through specific training and easy-to-apply protocols and to have more time per patient and a specific circuit that preserves the privacy of patients. To increase the awareness of their colleagues, they proposed raising awareness, training and knowledge of the protocols, empathising, appealing to our position as agents of early detection and our moral, legal, and social duty, and considering it an individual and community health problem.

As limitations of the study, apart from those inherent to the cross-sectional study, it would be worth investigating the causes of the low response rate and the high rate of non-responders to open-ended questions. Although the health sector has a higher representation of women, the imbalance in the gender ratio is an awareness bias. Closed questions should be restricted to the most repeated options referred to in this and previous studies.

As main conclusions, professionals in health care institutions have an average level of knowledge, are more aware and trained, are less influenced by stereotypes, are aware of legal obligations and still have structural problems, mainly related to training and awareness, and work overload. Actions are needed to homogenise training differences between services and professional categories and multidisciplinary work teams to identify the specific difficulties of workers in the early detection of cases of IPV.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Elia Pérez Fernández, for her help with the statistical analysis. Research, Methodological Support and Data Analysis Unit. University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón. Angélica Fajardo Alcántara and Eduardo Olano Espinosa for their help in the dissemination of the survey in the health centres “Pedro Laín Entralgo” Health Centre and “Los Castillos” Health Centre, Alcorcón. To the SUMMA 112 Research Commission and the Research Support Unit of the Primary Care Management for their willingness to participate in the study. To the Gender Violence Commission of the University Hospital Fundación Alcorcón for the dissemination of the survey. To all the professionals who responded to the survey.