Investigating the Causes of the High Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Illnesses in Du Noon Township

- 1. Department of Metro Health Services, Western Cape, South Africa

- 2. Division of Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Abstract

Background: In South Africa, STIs or sexually transmitted infections represent a significant public health issue. STIs are acknowledged as one of the main causes of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) epidemic and as a significant contributor to the illness burden in South Africa. The HIV population in Du Noon CHC in the Western Cape, South Africa, is around 8,000 persons. This study aims to investigate the potential causes of the high prevalence of STIs in the Du Noon population.

Methods: A cross-sectional study involving 40 participants between the ages of 18 and 45 was carried out. Both structured questionnaires and one-on-one patient interviews with open-ended questions were utilized to collect data.

Results: Cultural beliefs, having multiple partners, a lack of partner notification, alcohol consumption, and a lack of condom usage were found to be the main contributing factors to the high incidence of STIs. Sex education at schools appears to be lacking or not in sufficient detail to inform students. It reflects the other well-known cultural and socioeconomic issues confronting South African rural communities, e.g., poverty and sex, age-disparate relationships, and polygamous relationships.

Conclusion: The widespread preliminary understanding and framing of HIV as an STI and how it is transmitted needs further investigations and research. There is an urgent need to shift cultural ideologies and norms among the youth. This study highlighted how health education challenges, interpersonal relationships, and socioeconomic barriers are still important factors in STI transmission.

Keywords

• Sexually transmitted infections

• Primary health care

• Risk factors

• Knowledge

• Prevalence

• HIV

• Health education

• Aetiology

CITATION

Isaacs AA, Dookhth ABF, Razack A (2024) Investigating the Causes of the High Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Illnesses in Du Noon Township. JSM Sexual Med 8(1): 1134.

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a major public health concern in South Africa [1]. South Africa’s burden of disease due to STIs is currently one of the largest in the world [2,3]. The prevalence of STIs is relatively high and can lead to an increased risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and infertility [3- 5]. The burden of HIV has historically been heavy and continues to be a serious public health problem in South Africa [6]. Patients with STIs face an increased biological risk of HIV acquisition because of the virus’ invasion of the immune system through genital lesions and/or inflammation caused by STIs [7]. In South Africa, numerous studies on STIs have been done in the last 10 years. Most of them have shown that there is a link between STIs and HIV. It is most likely that other STIs are a contributing factor in transmitting HIV at a higher rate [3-5,8-15].

STIs remain a hidden epidemic in South Africa, with 7.9 million people living with HIV in 2017 [16]. It was estimated that there were 2.3 million new cases of gonorrhoea, 1.9 million new chlamydia cases, and 23,175 new syphilis cases among women aged between 15 and 49; among men of the same age, there were an estimated 2.2 million new cases of gonorrhoea, 3.9 million new cases of chlamydia, and 47,500 new cases of syphilis [16]. The interrelationships between HIV and STIs mean that an understanding of the burden and transmission patterns of STIs is imperative [17-19].

In South Africa, the epidemiology of STIs has been largely neglected. The historical lack of interest in STIs as a health priority and the absence of a surveillance system resulted in difficulties in collecting data from a fragmented health care system. Facility-based ad hoc surveys have provided some point estimates of the burden of the disease. A broad, cohesive picture of the state of STIs in South Africa is missing [19]. A major co- factor in such transmission is the presence of other sexually transmitted infections [4,14,20-23].

A 2016 study showed that bacterial STI prevalence rates in South Africa are relatively high, even compared to other African countries [14]. It is estimated that one in four women in South Africa is infected with at least one bacterial STI. The burden of STIs in South Africa is estimated to be higher in women than in men [14,24]. A study done in 2020 on the high prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted infections among women living in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa, concluded that there is extremely high prevalence of 83.3% and incidence of 36.6% of STIs that are HIV positive among women living in rural and urban communities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa [4].

A descriptive cross-sectional study showed that STI knowledge levels did not appear to have any effect on perceptions of the risk of acquiring STIs or the relationship between STIs and HIV transmission [10]. A study was done in 2017 in Malaysia among university students, assessing their knowledge, attitudes, risky behaviors, and preventive practices related to sexually transmitted diseases. The conclusion was that knowledge on the non-HIV causes of STIs is still lacking, and the risky behavior practiced by the sexually-active students in this study was quite alarming [25].

A study in 2019 concluded that the implementation of educational awareness programs in schools and campaigns for knowledge raising about STIs in urban and rural areas at the national level will increase awareness and willingness for screening and decrease STI transmission and discrimination in Africa [26].

It has been observed from a study done in rural areas of Eastern South Africa that sexual behavior is the most important determinant of the burden of HIV and sexually transmitted infections [20]. Another study concluded that there is a relationship between age and sexual behavior and confirmed that younger women are known to engage in higher-risk sexual behavior and have a higher number of concurrent sexual partners. Knowledge of the partner’s HIV status was low among women, and HIV-infected women reported a higher lifetime number of sexual partners [20].

To address the concern about sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted infections, there was a study done in various sub- Saharan African countries and the USA. It was concluded that sexual behaviors vary coherently between different populations and ethnic groups. Sexual behavior is also one factor responsible for a high risk of STIs [27]. In a study published in 2007, it was found that the low socio-economic status of women has also played an important role in promoting the spread of STIs and is a continuing obstacle to STI prevention efforts [24].

The purpose of this study is to gain a better understanding of the Du Noon community’s level of knowledge and attitudes towards STIs in order to have targeted interventions. This study could lead to a better understanding of STIs among the Du Noon community. Reducing the incidence of STIs can reduce high patient numbers, HIV transmission, adverse pregnancy events, and infertility. This study will aim to explore factors that may contribute to the high prevalence of STIs in the township of Du Noon, with specific objectives to assess patients’ knowledge of STIs, cultural and religious beliefs around sexual behavior, the relationship between socioeconomic factors and sexual behavior, and the sexual behavior of young adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

A cross-sectional study design was used, similar to that of Folasayo AT et al., [25]. A cross-sectional study is an observational study that involves the analysis of data collected from a population, or a representative subset, at one specific point in time and measures both the exposure and the outcome of interest at the same point in time [28]. This design has been chosen as it allows participants in the study to participate in an open-ended interview as well as complete a structured questionnaire in order to explore the reasons for the high incidence of STI in this community.

Setting

Du Noon is a small township situated in Milnerton, Cape Town, South Africa. Its population consists mainly of black Africans (89.3%), who are mostly Isi Xhosa speakers [17]. It has a formal and dedicated community health center (CHC) that has been operational since 2015 [18]. Du Noon CHC has a large HIV population of approximately 8000 people, and recent data from November 2019–February 2020 showed 1760 people being treated for STIs [17,18].

The study population consisted of young adults between the ages 18 – 40 years. This age range was chosen as this study wanted to focus on younger adults as older patients may be in the minority and have different reasons for re-infection than younger patients. Other inclusion criteria included, a confirmed diagnosis of STI (based on the history and clinical examination), both males and females, and mentally competent to give informed consent. Pregnancy was an exclusion criteria as their discharge may have been physiological and not due to an STI.

Based on an estimated prevalence of STIs from the facility’s data of 20%, a confidence incidence of 90%, and a margin of error of 5%, a sample size of 171 was obtained [28]. A random sampling method would have been preferred, but due to time and resource limitations as well as the COVID-19 pandemic limiting patient admissions for less serious conditions, this was not possible. The sampling method was then purposive, with an eventual sample size of 40 participants.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Du Noon CHC attended to walk-in and unbooked clients by screening for COVID-19 at the entrance of the clinic. Those without COVID-19 symptoms were allowed to form part of the walk-in queue. Strict precautions were taken by the health staff of the clinic by wearing personal protective equipment, applying social distancing among the walk- in patients, and using hand sanitizers. Consent was obtained both verbally and in writing prior to the interviews by the researcher

Data collection

One-on-one patient interviews using a structured questionnaire were used to gather data. The questionnaire used was adapted from validated and reliable questionnaires from previous studies [25,29,30]. The questionnaire expands on questions asked in previous studies that explored basic knowledge of STIs, the accessibility of condoms, and the importance of partner notification [25,30]. Positive and negative framing questions were used to improve the reliability of answers. Each answer had seven possible response items, so more detailed information was gathered. Open-ended questions were also asked to explore beliefs and social influences around STIs.

A Likert scale was used for the scoring questions. This is a scale used to represent people’s attitudes toward a topic. A 7-point Likert scale, for example, to score agreement will include options such as: strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree, and agree, while 7-point Likert examples for frequency and satisfaction follow the same manner.

Participants presenting to the walk-in clinic who meet the criteria for screening for symptoms of an STI were invited to participate in this study. Recruitment of patients occurred over a period of 2 weeks in May 2021. The recruitment process was primarily done by the researcher. An enrolled nurse assistant (ENA) working at Dunoon CHC formed part of the team to assist with translation when required. This was arranged and agreed upon by the Dunoon CHC OPD Operational Nursing Manager.

Interviews were conducted in the participant’s language of preference, such as Isi Xhosa and Shona, with the help of the ENA when there was a need. The interviews were conducted at the Du Noon Community Health Center in a dedicated and private consultation room, located some distance from the general patient flow.

Data analysis

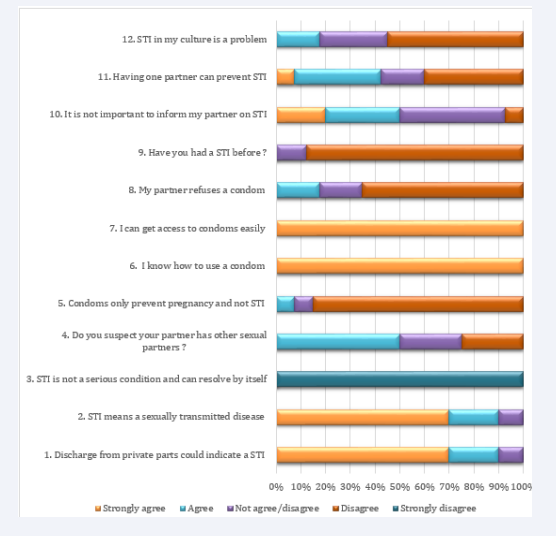

All interviews were recorded on audiotape and transcribed verbatim. For the open-ended questions, topics were identified and coded inductively from the text and then grouped together into coherent categories. The answers to the Likert survey questions were examined and explored. Answers are displayed as a summary on the graph below. When most of the answers were common and toward the ends of the scale, these statements were taken as important and significant.

The audio records of the interviews as well as the questionnaires were stored securely on a password-protected computer or in a locked cabinet. The information obtained was only accessible to the principal researcher and the supervisors.

Ethical considerations

Ethical oversight for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, of the University of Cape Town (HREC ref: 068/20210. Approval for the study was obtained from the Provincial Research Committee and Metro District, as well as from the facility manager of the Du Noon CHC.

Participants were informed verbally about the study and received a description of the intended use of the data that was collected. The time required for participation and the role of the researcher as non-interfering and non-judgmental were explained. Each participant was asked to sign a consent form by the primary researcher prior to participating in the interviews.

It was made clear to the participants that they had the right to freely decide what information they shared with the researcher and whether it could be used or not. The participants had the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Participation or withdrawal from the study did not affect their treatment course on the day of the interview or in the future. Participants were assured that the information obtained from them would be treated as confidential. No names of participants would be used, neither on the questionnaire nor during the recording of the information obtained.

Due to the nature of in-depth interviews and the sensitivity of the topic chosen, there was a risk of participants becoming emotionally distressed or feeling stigmatized. The researcher was aware of this possibility and actively looked out for signs of distress. If this occurred during the interview, the interview was stopped and the needs of the participant were attended to. Sufficient time was allocated to express any significant emotion. In the event that a participant experienced significant emotional distress, an appropriate mental health screening was carried out. A referral to the appropriate clinician, counsellor, or social worker who is readily available at the CHC was then made.

RESULTS

The total number of respondents approached by the researcher was fifty, and forty were found to be eligible. Ten respondents were not eligible due to various reasons, such as being younger than 18 years old, already on the ARVs, or not living in the Du Noon community. Information saturation was obtained from the forty participants for the open-ended questions.

Table 1,2 below shows the gender distribution and whether they were South African or not.

Table 1: Gender distribution and nationality

|

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

South African |

15 (37.5%) |

9 (22.5%) |

24 (60%) |

|

Non-South African |

12 (30%) |

4 (10%) |

16 (40%) |

|

Total participants |

27 (67.5%) |

13 (32.5%) |

40 (100%) |

Table 2: Age distribution of the participants

|

Age group (years) |

Male |

Female |

|

19-25 |

7 (17.5%) |

5 (12.5%) |

|

26-35 |

12(30%) |

8 (20%) |

|

>35 |

5 (12.5%) |

3 (7.5%) |

Figure 1 indicates that 90% of the participants have a general understanding of what an STI means and that a genital discharge can indicate an STI (question 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Summary of the survey questions

In question 3, everyone disagreed, meaning they all felt that STIs are serious conditions that require treatment. Many suspected that their partner may have other sexual partners (50%), and some seemed uncertain (25%). Responses to question 5 showed that most participants knew that condoms could prevent STIs. All knew how to use a condom, and all had access (question 6 and 7). Interestingly, less than 20% said their partner refused to use condoms, while 20% were uncertain (question 8). In question 9, most (90%) said they did not have a previous STI. When asked about the importance of notifying partners and having one sexual partner, we got a mixed response (question 10 and 11). Answers regarding culture and STI also evoked a mixed response.

The open-ended questions identified some similar themes to the questionnaire themes, i.e., patients’ knowledge of STIs, culture and religious beliefs around sexual behaviour, the relationship between socioeconomic factors and sexual behaviour, and the sexual behaviour of young adults. The following additional themes were identified by the open-ended questions:

Sources of knowledge about STIs

Most of the respondents obtained information on STIs from two major sources: elder siblings or friends. The life orientation class at high schools only briefly touched base on what STIs are. The participants attributed the main reason for not being well informed at school about STI to the ‘shyness’ of the teachers when speaking about this topic to them.

Condoms usage

Most participants who were in a long-term relationship with their partner did not use condoms. The reason included less sensation and pleasure when using condoms, and by using condoms, trust in the relationship is not encouraged. Alcohol consumption seemed to reduce condom usage.

Female Participant No. 1:

‘I was head over heels in love with him. Whatever he said goes. But honestly, while I was with him, getting a sexual infection at that time never came to my mind.’

Female Participant No. 3: ‘Only the first time (I used a condom), but then afterwards it was direct contact. He says he enjoys being with me like that. I am fine with it because I love him and will do anything to keep him happy.’

Female Participant No. 11: ‘I think being in a stable relationship makes it a normal practice to not use condoms. When you are having a fling sex with a friend. You know the thing about “friends with benefits,” since you’re not really in a relationship with that person, and then you use it mostly because you don’t want a bun in the oven.’

Male participant No. 7: ‘If I am drunk at a party or club and then meet a girl, obviously, we are going to have sex without condoms. That’s because sex under the influence of alcohol is always another story. When booze hits hard, you don’t think of condoms, and the girls always love it like that.’

Culture and peer pressure

Men were more likely than women to say that peer pressure encourages them to have multiple sexual partners. They also discussed isiXhosa men’s masculinity and how their ethnicity is linked to perceptions of greater sexual prowess that are perpetuated by the community and social media. It has been pointed out by several participants that peer pressure can force teenagers to initiate sexual activity during high school.

Lack of fulfilment of sexual needs by one sexual partner, a desire for ‘variety,’ ‘lust,’ and the fact that it is a ‘biological thing’ were frequently cited as motivators, particularly among males.

Male participant No. 3: ‘Let me explain to you, for example, when a guy and a woman have been together for a long time and she’s busy or tired sometimes, this results in a loss of interest in intimacy, so eventually the guy will have to satisfy himself elsewhere. But there is still love between them, so it can happen that she ends up getting STIs that way.’

Male Participant No. 5: ‘Being young, it doesn’t cross your mind of getting STIs by swapping partners. It happened mostly due to peer pressure. I can recall such situations in my younger days where it was just me and my group of friends. Well, at that time it was, what you want, you go for it.’

Male Participant No. 7: ‘To be promiscuous it’s something encouraged amongst young IsiXhosa men by older men in our culture, so I think that might be a reason.’

Male Participant No. 17: ‘Well, the need for a change, I would say, that’s why, when you meet a new partner, the sex always tastes different. The reaction always surprises you. Usually, you get bored of a monotonous sex life, always same position or same reaction. It’s like the menu is always the same; there is no change. I want to feel different, else the fun in sex is lost. You need to spice up your sex life. But then you never think of STIs at this moment.’

Male participant No. 21: ‘Yes, but it’s not only a man thing; its equality of gender in everything nowadays! I know personally women who got fed up of their guys. This usually happens when the guy is a long-distance driver, so he is away for 3-6 months, and obviously the woman will look around to have sex. She needs to fulfil her natural need. I think you cannot blame her. Her guy is there, but away too long. I can assure you that her guy is also getting his share there wherever he is; he has his needs, and she knows that also.’

Socio economic

It was observed that with both men and women who were in a previous relationship resulting in a child, sex was sometimes used to secure finances. Some of the participants associated sex with money, i.e., as a way to get out of poverty.

Female Participant No. 10: ‘It became a more casual kind of thing when I recall it, and we usually enjoy the sex without the use of condoms. He knows I am on the pill, and the best part is he will usually leave me some extra cash.’

Female participant No. 28: ‘I prefer going out and having sex with more mature guys; I mean working men. They will always buy or bring me something, like a phone or perfume. Take me for a nice meal in a restaurant. I get to enjoy things that are out of my reach. You feel upgraded in status.’

Substances

All participants agreed strongly that alcohol and drugs increase risky sexual behavior. Alcohol easily takes the drinkers into a state of promiscuous behavior and makes them act with audacity and without restraint, which makes them riskier. The participants stated that the failure to use condoms during intercourse is mostly caused by the loss of inhibition caused by alcoholic drinks.

Social Media

Some interviewees stated that social media played a key role in shaping, preserving, and promoting cultural notions of masculinity, gender norms, and sexuality, which, in turn, impacted young adult generations’ perspectives. Dating sites are utilized to help other men and women find various partners effortlessly. Changing standards and attitudes towards sex are also thought to enhance the risk of STIs through the ease of meeting sex partners online.

Partner notification

Male participants were more likely than female participants to be in multiple relationships at the same time. Because there are few, if any, contact details, notifying all partners is difficult. Unwillingness to see the partner again, as well as thoughts of them being the source of infection, hampered notification of the other partners. All participants agreed that it was important to test themselves for HIV and notify their partner to prevent the spread of STIs. Female participants were worried about their health in general or knew their partners had other partners and recognized how notification could avoid re-infection.

Female Participant No. 30: ‘My visit to the clinic today is mostly because I found that my partner has stepped out. He told me he still enjoys sex with me as well. The last time he met with the other guy. He told me that he has been using the condoms, but I know it is a lie since, with me, he never likes to use them. So, I just came for a check-up as I am afraid of catching something down there.’

Participant No. 30: ‘He wanted out of the blue to try different things while having sex with me. When I asked him, he agreed and stepped out. He says that he feels he enjoys it more with me if we try new things. I am somewhat scared and came for a check- up.’

Male Participant No. 17: ‘It’s useless to inform her because I won’t see her again.’

Male participant No. 21: ‘I am a long-distance truck driver. I am a lot of time away from my wife. I am 45 years old. I cannot risk having my marriage blown up by informing my wife of my one-night affairs. I will just get treated, and then after a week I will drive back home to her.’

Male participant No. 35: ‘I have a new girlfriend now, and every now and then I shack up with my ex-girlfriend. If I end up catching something with my ex, now I have to notify my present girlfriend, which will just ruin this new relationship.’

DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to explore factors that contribute to the high incidence of STIs within the Dunoon community. The survey questions indicated that participants knew what an STI was, how it presents, and that it needs to be treated. They knew that condoms can prevent STIs, how to use them, and had easy access to them. Despite knowledge of STIs and how to prevent them, high-risk behaviour still ensued. Cultural beliefs, having multiple partners, a lack of partner notification, alcohol consumption, and a lack of condom usage are all contributing to the high incidence of STIs.

These themes were further explored in the open-ended questions. Cultural ideas and understandings of sexual relationships among older men seem to influence younger generations. This, along with peer pressure and social media, seems to create a norm and desire to have multiple sexual partners. A lack of sexual fulfilment may also indicate that some men are not in committed, loving relationships. There is little alternative information about the benefits of aspiring to a loving, secure relationship. School teachers seem to shy away from teaching appropriate and detailed information about STIs.

The socio-economic challenges of the community negatively affect young females. Young females in need of financial support are drawn to males who may be financially empowered and in need of sexual gratification and masculine status. These core values and social problems make it easier to understand why condom usage is low and partner notification is difficult. Adding to the above problem is the high incidence of alcohol usage and the lack of inhibition that results from its use. This was like other studies that showed high usage of alcohol across South Africa and its influence on risk behavior and interpersonal violence [31-38].

Our study emphasizes the significance of raising STI awareness and incorporating sexual and reproductive health into education systems. This was also demonstrated in a 2016 study done in the Platfontein San Community [31]. Our study highlighted the effects of social economic burden and its relationship to STI, similar to the study done in the Mopani district [32]. This was also evident in 2017 study, which spoke about the link between socioeconomic status and HIV as the most common STI, which has been on the rise in the Free State and Western Cape provinces of South Africa [33].

Results from our study echoed themes and broader ideas from other studies [4,10,25]. It reflects the other known cultural and social-economic problems facing rural communities in South Africa [34]. A study published in Health Communication Research (2011) looked at language choice and sexual communication among isiXhosa speakers in Cape Town, South Africa. This study explores culture and communication and validates findings about cultural problems leading to high STI transmission [35].

Our study added to knowledge in that it explored the cultural influence on sexual behaviour and further highlighted social and economic reasons why women may show risky behaviour despite a good understanding of STIs and prevention.

The results obtained in this study only represented those who attended the Du Noon CHC within those 2 weeks of the survey (n = 40). The results may therefore not adequately reflect the views of the broader community. The survey was done during the COVID-19 level 3 alert lockdown, which may have added extra social and economic strain on participants as well as health- seeking behavior. Some participants were not fluent in English, and a translator was used. In these interviews, some information may have been lost in translation. Only one interviewer was used due to resource constraints. More males were interviewed than females, possibly skewing the data.

The following provisions were made in this study to promote credibility: The open-ended questions were used to rule out possible biases in the survey. The respondents were free to express their opinions about the questions asked. Maintaining good rapport and setting participants at ease during the interview process. Using verbal and non-verbal cues to encourage confidentiality and a non-judgmental atmosphere. Confidentiality and voluntary inclusion in the study were ensured and reminded of at various points in the interview process. Survey questions had a mixture of positive and negative framing to avoid bias.

The triangulation of information was further reached by allowing all the participants to answer the survey and by further checking and exploring their answers to the open-ended questions. During the interview process, answers were checked and read back to participants, making sure of the content recorded.

Implications for clinical practice

Behavioral changes remain the most complex and difficult to address. While secondary prevention and treatment methods at the clinic level must be robust and up-to-date, primary prevention may require multidisciplinary approaches. The focus on youth-friendly services providing alternative explanations from cultural, social media, and peer pressure information may be one area to focus on. Youth role models can also assist in empowering youth. Community-oriented primary care may also see more clinical nurses, medical officers, and health promoters promoting health in the community and utilizing social media to spread messages that may reduce risky sexual behavior. Although the study’s findings may only be applicable to this community, they may have an impact on other communities with comparable populations. Overall, the widespread preliminary understanding and framing of HIV as an STI and how it is transmitted needs further investigations and research. This study filled a gap in the local literature by highlighting how health education challenges, interpersonal relationships, and socioeconomic barriers are still important factors in STI transmission.

There is an urgent need to shift cultural ideology and norms among the youth of the Du Noon community. Adequate and correct information is essential for youth before they begin sexual activity. Health care professionals from the CHC could be allowed to give talks in schools. This will also be an important step in disseminating STI knowledge among this community’s youth. Regular STI screening and treatment at the community level may aid in the reduction of STI spread.

CONCLUSION

Participants had a decent understanding of what a STI was, how it manifests, and how to treat it. They had easy access to condoms, knew how to use them, and were aware that they can prevent STIs. High-risk conduct continued despite knowledge of STIs and how to prevent them. The high frequency of STIs is largely due to cultural attitudes, multiple partners, lack of partner notification, alcohol consumption, and non-use of condoms. Older men’s cultural perspectives and understandings of sexual interactions appear to have an impact on younger generations. The youth must urgently change their cultural views and conventions. This study brought to light how STI transmission is still largely influenced by interpersonal relationships, socioeconomic hurdles, and problems with health education

FUNDING

The study was funded by the researchers.

REFERENCES

- Wilkinson D, Karim SSA, Harrison A, Lurie M, Colvin M, Connolly C, et al. Unrecognized sexually transmitted infections in rural South African women: a hidden epidemic. Bull World Health Organ. 1999; 77: 22-28.

- Johnson L, Bradshaw D, Dorrington R. The burden of disease attribute to sexually transmitted infections in South Africa in 2000. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:658-662.

- Naidoo S, Wand H, Abbai N, Ramjee G. High prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted infections among women living in Kwazulu- Natal, South Africa. AIDS Res Ther. 2014; 11: 31.

- Kharsany ABM, McKinnon LR, Lewis L, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Maseko DV, et al. Population prevalence of sexually transmitted infections in a high HIV burden district in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Implications for HIV epidemic control. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 98: 130–137.

- Naidoo S, Wand H, Abbai NS, Ramjee G. High prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted infections among women living in Kwazulu- Natal, South Africa. AIDS Res Ther. 2014; 11: 31.

- Pham-Kanter T, Steinberg MH, Ballard RC. Sexually transmitted diseases in South Africa.Genitourin Med. 1996; 72: 160–171.

- Wood JM, Harries J, Kalichman M, Kalichman S, Nkoko K, Mathews C. Exploring motivation to notify and barriers to partner notification of sexually transmitted infections in South Africa: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2018; 8: 980.

- Dubbink JH, van der Eem L, McIntyre JA, Mbambazela N, Jobson GA, Ouburg S, et al. Sexual behaviour of women in rural South Africa: a descriptive study. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16: 557.

- Dubbink JH, Van Der Eem L, McIntyre JA, Mbambazela N, Jobson GA, Ouburg S, et al. Sexual behaviour of women in rural South Africa: A descriptive study. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16: 557.

- Nyasulu P, Fredericks M, Basera TJ, Broomhead S. Knowledge and risk perception of sexually transmitted infections and relevant health care services among high school students in the Platfontein San community, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018; 9: 189–197.

- Joseph Davey DL, Nyemba DC, Gomba Y, Bekker LG, Taleghani S, DiTullio DJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy in HIV-infected and- uninfected women in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2019; 14.

- Rees K, Radebe O, Arendse C, Modibedi C, Struthers HE, McIntyre JA, et al. Utilization of Sexually Transmitted Infection Services at 2 Health Facilities Targeting Men Who Have Sex with Men in South Africa: A Retrospective Analysis of Operational Data. Sex Transm Dis. 2017; 44: 768-773.

- Mudau M, Peters RP, De Vos L, Olivier DH, J Davey D, Mkwanazi ES, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections among human immunodeficiency virus-infected pregnant women in a low-income South African community. Int J STD AIDS. 2018; 29: 324–333.

- Francis SC, Mthiyane TN, Baisley K, Mchunu SL, Ferguson JB, Smit T, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among young people in South Africa: A nested survey in a health and demographic surveillance site. Low N, editor. PLOS Med. 2018; 15.

- O’Leary A, Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Teitelman A, Heeren GA, Ngwane Z, et al. Associations between psychosocial factors and incidence of sexually transmitted disease among South African adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2015; 42: 135–139.

- Kularatne RS, Niit R, Rowley J, Kufa-Chakezha T, Peters RPH, Taylor MM, et al. Adult gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis prevalence, incidence, treatment and syndromic case reporting in South Africa: Estimates using the Spectrum-STI model, 1990-2017. PLoS One . 2018;13.

- Dunoon, Cape Town.

- Sub Place Dunoon. Census 2011.

- Pham-Kanter GB, Steinberg MH, Ballard RC. Sexually transmitted diseases in South Africa. Genitourin Med. 1996; 72: 160-171.

- Dubbink JH, Van Der Eem L, McIntyre JA, Mbambazela N, Jobson GA, Ouburg S, et al. Sexual behaviour of women in rural South Africa: A descriptive study. BMC Public Health. 2016; 16: 557.

- Lowe S, Mudzviti T, Mandiriri A, Shamu T, Mudhokwani P, Chimbetete C, et al. Sexually transmitted infections, the silent partner in HIV- infected women in Zimbabwe. South Afr J HIV Med. 2019; 20:849.

- Kaida A, Dietrich JJ, Laher F, Beksinska M, Jaggernath M, Bardsley M, et al. A high burden of asymptomatic genital tract infections undermines the syndromic management approach among adolescents and young adults in South Africa: Implications for HIV prevention efforts. BMC Infect Dis. 2018; 18: 499.

- Torrone EA, Morrison CS, Chen P-L, Kwok C, Francis SC, Hayes RJ, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis among women in sub-Saharan Africa: An individual participant data meta-analysis of 18 HIV prevention studies. Byass P, editor. PLOS Med. 2018; 15: e1002511.

- Kularatne RS, Niit R, Rowley J, Kufa-Chakezha T, Peters RPH, Taylor MM, et al. Adult gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis prevalence, incidence, treatment and syndromic case reporting in South Africa: Estimates using the Spectrum-STI model, 1990-2017. PLoS One. 2018; 13.

- Folasayo AT, Oluwasegun AJ, Samsudin S, Saudi SNS, Osman M, Hamat RA. Assessing the knowledge level, Attitudes, Risky Behaviors and Preventive Practices on Sexually Transmitted Diseases among University Students as Future Healthcare Providers in the Central Zone of Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017; 14:159.

- Badawiid MM, Salaheldin MA, Idris AB, Hasaboid EA, Osman ZH, Osman WM. Knowledge gaps of STIs in Africa; Systematic review. Meta-Analsis. 2019; 14: e0213224.

- Wingood GM, Reddy P, Lang DL, Saleh-Onoya D, Braxton N, Sifunda S, et al. Efficacy of SISTA South Africa on Sexual Behavior and Relationship Control Among isiXhosa Women in South Africa. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013; 63: 59–65.

- Setia MS. Methodology series module 3: Cross-sectional studies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016; 61: 261-264.

- Soleymani S, Abdul Rahman H, Lekhraj R, Mohd Zulkefli NA, Matinnia N. A cross-sectional study to explore postgraduate students’ understanding of and beliefs about sexual and reproductive health in a public university, Malaysia. Reprod Health. 2015; 12: 77.

- Folasayo AT, Oluwasegun AJ, Samsudin S, Saudi SNS, Osman M, Hamat RA. Assessing the knowledge level, Attitudes, Risky Behaviors and Preventive Practices on Sexually Transmitted Diseases among University Students as Future Healthcare Providers in the Central Zone of Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017; 14:159.

- Nyasulu P, Fredericks M, Basera TJ, Broomhead S. Knowledge and risk perception of sexually transmitted infections and relevant health care services among high school students in the Platfontein San community, Northern Cape Province, South Africa. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018; 9: 189–197.

- van der Eem L, Dubbink JH, Struthers HE, McIntyre JA, Ouburg S, Morré SA, et al. Evaluation of syndromic management guidelines for treatment of sexually transmitted infections in South African women. Trop Med Int Heal. 2016; 21: 1138–1146.

- Bunyasi EW, Coetzee DJ. Relationship between socioeconomic status and HIV infection: findings from a survey in the Free State and Western Cape Provinces of South Africa. BMJ Open. 2017; 7: e016232.

- Kehler J. Women and Poverty: The South African Experience. J Int Womens Stud. 2001; 3: 41–53.

- Cain D, Schensul S, Mlobeli R. Language choice and sexual communication among Xhosa speakers in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for HIV prevention message development. Health Educ Res. 2011; 26: 476–488.

- Chauke TM, Van Der Heever H, Hoque ME. Alcohol use amongst learners in rural high school in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2015; 7: 1-6.

- Nkosi S, Rich EP, Morojele NK. Alcohol use, sexual relationship power, and unprotected sex among patrons in bars and taverns in rural areas of north west province, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2014; 18: 2230–2239.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Cain D, Cherry C. Sensation seeking, alcohol use, and sexual behaviors among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006; 20: 298–304.