Leptospirosis in Iran: A Gender- Based Association

- 1. Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

- 2. Department of Epidemiology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

- 3. Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

- 4. Department of Biostatistics, Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

ABSTRACT

The gender-based association has always been neglected in all epidemiologic studies of leptospirosis worldwide. The present analytical study focuses on the significance of gender in susceptibility to leptospirosis. The target population includes all identified patients with leptospirosis in Golestan province, located in northern Iran, between 2011 and 2023. Data was collected and coded using SPSS software and analyzed using chi-square tests, independent t-tests, multiple logistic regression as well as Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. Overall, 316 diagnosed patients were included in the study. The gender proportion in leptospirosis incidence favors males, with a ratio of 3:1. The highest frequency of patients was among males (73.7%). The mean age was 45±16 years for males and 47±15 years for females. In terms of seasonal association, the highest frequency was occurred between July and August (21.9%) for males and in July alone (21.7%) for females. Overall, no significant relationship was found between occupational groups and potential disease sources by gender. However, examining the frequency ratio of disease occurrence in gender subgroups reveals a significant distribution in the rice farmers compared to other occupation subgroups (p<0.001). Nonetheless, the reasons behind these distributions and differences needs more investigations.

KEYWORDS

- Leptospirosis

- Gender-based association

- Iran

CITATION

Sahneh E, Delpisheh A, Sayehmiri K, Kaghazi B (2024) Leptospirosis in Iran: A Gender-Based Association. JSM Sexual Med 8(4): 1141.

INTRODUCTION

Leptospirosis is a contagious infectious disease [1]. In some Asian and Pacific countries, its incidence rate is high. Leptospirosis is caused by a bacterium called Leptospira. This disease is considered the most common and widespread zoonosis worldwide [2,4]. There are few studies regarding the role of gender in susceptibility to leptospirosis globally. Higher incidence rates have been observed in males [3]. The male- to-female ratio for leptospirosis incidence is 5:1 in Germany, 10:1 in France and Italy [4], and 9:1 in Albania [8]. The risk of contracting leptospirosis in males increases after puberty [5,6]. The higher number of cases in the male population may be due to physiological responses or differences in exposure intensity to the infectious agent. Host response to infection may differ between males and females [7]. This could be because males are more frequently exposed to disease reservoirs and sources [6]. However, the reasons behind these distributions and differences remain largely unknown [8]. Men are more often engaged in outdoor occupations related to rice fields, sugarcane, mining, waste and sewage, animal husbandry, veterinary services, slaughterhouses, fishing, forestry, and water recreation [9].

In some Asian countries, certain groups of women are more at risk of contracting leptospirosis compared to men. In Asia and northern Iran, agricultural occupations, primarily in rice fields, are predominantly carried out by women. Nevertheless, in these countries, leptospirosis incidence among women is generally lower than among men [2]. Perhaps gender and physiological changes, levels of female hormones, or caregiving behaviors play a role in susceptibility to leptospirosis [10].

In Germany, 77.8% of patients with leptospirosis are males, and the proportion of hospitalizations among males is higher than females [22]. Studies measuring seroprevalence of leptospirosis in the general population indicate higher seroprevalence in males compared to females, reflecting past infection. In Brazil, the risk of leptospirosis infection in males is twice that of females, with male seroprevalence being 15% higher than females, a gap that widens with increasing age [3]. Contact with water contaminated with rodent urine, as well as contact with animals, can be potential risk factors for contracting this disease. Contact with infected animals such as cattle, horses, dogs, cats, pigs, deer, squirrels, foxes, mice, rats, raccoons, and marine mammals increases the chance of infection [11-15]. Transmission to humans mainly occurs through direct contact with the Leptospira bacteria via damaged skin, mucous membranes of the genitals, eyes, nose, mouth, ingestion, and washing the face with contaminated water [2,13]. Human-to-human transmission of the disease is rare [16].

Leptospirosis manifests acutely. Symptoms often include fever, chills, sweating, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, conjunctivitis, myalgia, headache, and jaundice, lasting from several days to two weeks. Early diagnosis of leptospirosis is desirable [17]. However, the disease outcome depends heavily on the severity and clinical condition of the patient. Individuals with underlying conditions, the elderly, pregnant women, and those with Weil’s syndrome (severe jaundice), renal failure, or impaired kidney function have a higher mortality rate. Without treatment, the disease progresses rapidly, leading to increased mortality [18]. Leptospirosis can be diagnosed using a blood serum test for specific Leptospira antibodies, at least five days after the onset of clinical symptoms [19]. The gold standard for diagnosing this disease is the microscopic agglutination test (MAT). Other diagnostic methods include ELISA and IFA tests [20].

With the expansion of climate change and the potential occurrence of related hazards such as floods, droughts, and an increase in rodent populations, the likelihood of disease outbreaks is increasing [21]. Leptospirosis is endemic in northern Iran. Given the public health importance of leptospirosis and its potential association with gender, as well as the differences in behavior and exposure between men and women to disease reservoirs and sources, further research is necessary to better understand gender-related factors in leptospirosis incidence in developing countries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is an analytical epidemiological study. For the first time, this study examines gender factors in human leptospirosis incidence in Iran. The target population includes identified and registered patients with leptospirosis in northern Iran across 14 counties of Golestan province from 2011 to the end of 2023. All cases were included in the study through a census. The disease confirmation criteria include positive blood serum samples using PCR method, IFA titers equal to or greater than 1:80, or IgM ELISA titers above 11. A total of 316 registered patients were included, and a 3-page checklist was completed for all patients. After data coding, the collected information was entered into SPSS software version 22 (Chicago, IL, USA) for analysis. Data were analyzed using chi-square tests, independent t-tests, multiple logistic regression, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The frequency of patients’ distribution by gender was categorized into 9 age groups.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

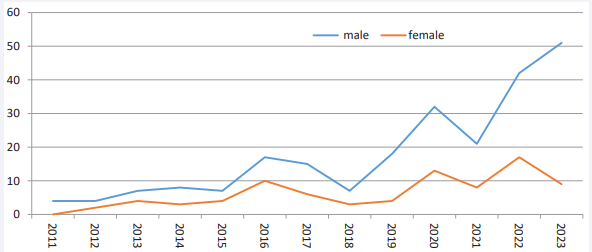

A total number of 316 patients were diagnosed. The percentage of cases in males is 73.7%. The male-to-female ratio of incidence was approximately 3:1. Overall, during the study years, the number of cases among males was higher than females (p<0.001) and 70% of the patients were from rural areas. The mean age was 45±16 years for males and 47±15 years for females. The average age in females was 1.6 years higher than in males statistically, but this difference was not significant (p=0.314). Despite the limited data in 2011, males were predominant (100%), and the highest frequency in females was in 2016 (37%) [Figure 1].

Figure 1 Frequency of leptospirosis by gender and year in Golestan province (2011-2023)

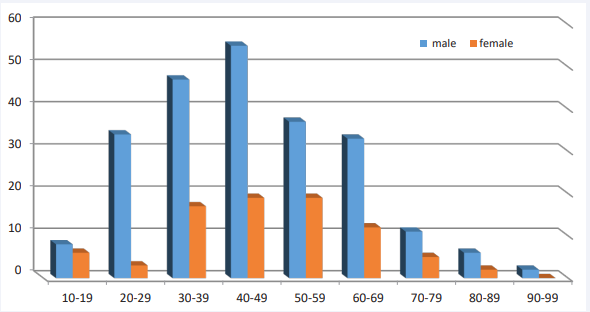

Due to its unimodal age distribution and the absence of a linear relationship with age, the quadratic model can also be utilized. Using this model, a significant relationship between disease outcome and age was observed (p=0.013). The highest frequency of patients (23.4%) was observed in the age group of 40-49 years. The distribution of the disease was similar for both genders. The frequency percentage in males was 73.7% and 26.3% in females [Figure 2].

Figure 2 Frequency of Leptospirosis by gender and age groups in Golestan province (2011-2023)

The highest frequency of cases was occurred in summer (57.2%), specifically in July with 21.8%, and the lowest number was observed in winter (3.2%), particularly in February with 0.63%. Regarding the relationship between gender and disease occurrence by month, the highest percentage of incidence was observed during July and August (21.9%) for males and in July (21.7%) for females.

In this study, the annual incidence of leptospirosis in the population of Golestan province was estimated at 13 per million. Out of the sample of 316 patients investigated, 14 patients died in the hospital due to leptospirosis. The mortality rate is higher among males than females; however, a statistically significant relationship between mortality and gender was not observed (p=0.314). The fatality rate of the disease was calculated to be 4.4%. No significant relationship was found between gender and urban versus rural residents (p=0.161), as well as between gender and months of the year (p=0.984) as addressed in [Table 1].

Table 1: Frequency of leptospirosis by gender, occupation, and potential disease sources in Golestan province (2011-2013)

|

variables |

Total N (%) |

Male N (%) |

Female N(%) |

|

|

Occupation |

Farmer (rice)* |

163 (51.6) |

118 (50.6) * |

45 (54.2) * |

|

Farmer (Other Crops) |

67 (21.2) |

60 (25.8) |

7 (8.4) |

|

|

Livestock farmer, hunter, fisherman |

23 (7.3) |

12 (5.1) |

11(13.2) |

|

|

Employee, student, military |

17 (5.4) |

12 (5.1) |

5 (6.1) |

|

|

Other jobs |

46 (14.5) |

31(13.3) |

15(18.1) |

|

|

P value |

0.788 A |

<0.001*B |

<0.001*B |

|

|

Sources |

History of contact with stagnant rice field water* |

172 (54.4) |

128 (54.9) * |

44 (53) * |

|

History of working in non- paddy farm |

36 (11.4) |

26 (11.2) |

10(12.1) |

|

|

Drinking water and washing face with stagnant water |

34 (10.8) |

22(9.4) |

12(14.4) |

|

|

History of contact with domestic animals and mouse droppings |

31(9.8) |

24 (10.3) |

7(8.4) |

|

|

Other, unspecified |

43(13.6) |

33(14.2) |

10(12.1) |

|

|

P value |

0.75 A |

<0.001*B |

<0.001*B |

|

Abbreviations: A: By Chi-square test; B: By Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

Regarding the relationship between occupational groups and gender, no statistically significant relationship was observed between these two variables (p=0.788). Examining the frequency ratio of disease occurrence within gender subgroups for fitness of distribution incidence with K-S test reveals that the distribution of this variable is not uniform across occupational groups. The incidence rate is significantly higher in the rice paddy farming occupational group (p<0.001). Similarly, in examining the relationship between history of contact with potential disease sources and gender, no statistically significant relationship was found between these two variables (p=0.753). Moreover, in assessing the frequency ratio of disease occurrence within gender subgroups based on the classification of potential disease sources, it was observed that the distribution of this variable is not uniform across categories, and the incidence rate is significantly higher in the subgroup with a history of contact with stagnant rice paddy water (p<0.001) as shown in [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

Given that the gender ratio in the community was approximately 1:1, we expect 50% of leptospirosis patients to be women. In this study, it was found that 26.3% of the female population was affected by the disease. A study was conducted in New Zealand between 1999 and 2008 shows that 88% of leptospirosis cases occur in men with occupations related to livestock and meat processing [38]. Similarly, a study in Germany from 1997 to 2005 showed that men are more hospitalized due to leptospirosis than women, and their symptoms are severe (p<0.001) [22]. Another study in Sri Lanka in 2012 also emphasized this point [23]. The results of this study indicate that the incidence rate among men was 2.7 times higher than that in women. However, understanding the results of these observations requires investigation into causal, biological, and social factors.

A study conducted in Brazil from 2000 to 2009 revealed that rural men of reproductive age are at a higher risk of leptospirosis (IRR=4.22, CI (3.09-5.76) [5]. Another study by Gilles Guerrier and colleagues in New Caledonia in 2013 discovered that adolescents display more classical features of the disease compared to children [24]. It seems that as male’s age, the likelihood of contracting the disease rises.

In some cases, the seroprevalence of leptospirosis in women is higher than in men. A study conducted in Malaysia in 2002 showed that the seroprevalence of leptospirosis in women (59.5%) with an average age of 42.2±18.7 is higher than in men [10]. It is likely that individuals employed in agriculture and livestock outside the home are at higher risk of leptospirosis compared to other occupations [25-30,36,37]. Studies assessing the seroprevalence of leptospirosis in rural populations in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic show that seroprevalence among men (29%) is higher than in women (19%). Risk factors for leptospirosis, such as walking barefoot and swimming in contaminated water, were significantly associated with seroprevalence levels in men [31]. However, the seroprevalence rates in specific populations such as serovars or serogroups should be interpreted with more caution [32].

Interpreting the results concerning gender requires careful consideration. It seems that the higher incidence among men may be attributed to their occupations. Exposure to recreational water activities, contact with livestock and animals, and agricultural occupations increase the risk of infection. The findings of this study also indicate that the highest prevalence of infection occurs in jobs related to rice paddies (51.6%) compared to other occupations, with men comprising 72.3% of this group. A study conducted in 2015 by Giefing-Kröll and colleagues revealed that socio-economic behaviors, such as increased exposure to pathogens during agricultural or occupational activities, make men more susceptible to infections caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, or fungi, such as leptospirosis [33].

Encounters and contact with animals can be potential risk factors for this disease. Contact with soil contaminated with the urine of house mice around the home is a significant factor for infection [8,12,14,15]. A study in Germany in 2009 showed that contact with pet mice (RR=13.89) and forestry occupations (RR=9.2) are the most important risk factors for leptospirosis [34]. Mechanics and automotive repair workers, due to their garages and workshops being located on the outskirts of cities, are more exposed to animals, especially mice, and are at higher risk [35]. The results of this research showed that the highest prevalence of patients resides in rural (70.8%) compared to urban areas (29.2%).

Traditionally, the increased risk of leptospirosis in men has been associated with increased occupational or recreational exposure to predisposing factors, especially contaminated waters and a history of animal contact [29,30,38]. According to Haake and colleagues, individuals in contact with animals in nature are more exposed to leptospirosis [39]. The results of this study indicate that a history of exposure to stagnant water in rice paddies is significantly associated with gender (p<0.001).

Gender differences in clinical manifestations of leptospirosis may lead to the lack of systematic evaluation and incorrect treatment of the disease in women. To prevent confusion in clinical practice, epidemiological investigation in suspected patients is crucial, and physicians should consider leptospirosis in women presenting with undifferentiated fevers. Several studies have addressed gender differences in overall mortality [40]. No significant association was found between gender with place of residence either rural or urban areas, months of the year, and symptoms of the disease, in consistence with a Brazilian study in 2024 [3].

CONCLUSION

Gender differences may play a role in susceptibility to leptospirosis. It ishypothesized that behavioral, genetic, hormonal, or immune system factors related to gender may be important in human leptospirosis. However, a significant association was observed between gender groups with agricultural occupations related to rice paddies, as well as history of exposure to stagnant water in rice paddies contributing to the onset of the disease. There is still insufficient evidence and information regarding gender-related immune responses and the interaction between sex hormones and immune cells in infectious diseases. Future cohort studies are needed to evaluate gender differences in biological and immune responses to leptospirosis and their role in clinical manifestations in patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors sincerely thank and appreciate all the staff of comprehensive health service centers in Golestan province as well as all individuals who collaborated in conducting this research.

REFERENCES

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, et al. Global morbidity and mortality of leptospirosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015; 9: e0003898.

- Sahneh E, Delpisheh A, Sayehmiri K, Khodabakhshi B, Moafi-Madani M. Investigation of risk factors associated with leptospirosis in the North of Iran (2011-2017). J Res Health Sci. 2019; 19: e00449.

- Delight EA, de Carvalho Santiago DC, Palma FA, de Oliveira D, Souza FN, Santana JO, et al. Gender differences in the perception of leptospirosis severity, behaviours, and Leptospira exposure risk in urban Brazil: a cross-sectional study. medRxiv. 2024.

- Leptospirosis worldwide, 1999. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1999; 74: 237-242.

- Guerra-Silveira F, Abad-Franch F. Sex bias in infectious disease epidemiology: patterns and processes. PloS one. 2013; 8: e62390.

- Díaz A, Beleña Á, Zueco J. The role of age and gender in perceived vulnerability to infectious diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17: 485.

- Gay L, Melenotte C, Lakbar I, Mezouar S, Devaux C, Raoult D, et al. Sexual dimorphism and gender in infectious diseases. Frontiers Immunol. 2021; 12: 698121.

- Puca E, Pipero P, Harxhi A, Abazaj E, Gega A, Puca E, Akshija I. The role of gender in the prevalence of human leptospirosis in Albania. J Infect Dev Countries. 2018; 12:150-155.

- Sánchez-Montes S, Espinosa-Martinez DV, Rios-Munoz CA, Berzunza- Cruz M, Becker I. Leptospirosis in Mexico: epidemiology and potential distribution of human cases. PloS one. 2015; 10: e0133720.

- Tolhurst R, De Koning K, Price J, Kemp J, Theobald S, Squire SB. The challenge of infectious disease: time to take gender into account. J Health Management. 2002; 4: 135-151.

- Suut L, Mazlan MN, Arif MT, Yusoff H, Abdul Rahim NA, Safii R, et al. Serological prevalence of leptospirosis among rural communities in the Rejang basin, Sarawak, Malaysia. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016; 28: 450-457.

- Vanasco NB, Schmeling MF, Lottersberger J, Costa F, Ko AI, Tarabla HD. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of human leptospirosis in Argentina (1999-2005). Acta Trop. 2008; 107: 255-258.

- Brockmann SO, Ulrich L, Piechotowski I, Wagner-Wiening C, Nöckler K, Mayer-Scholl A, et al. Risk factors for human Leptospira seropositivity in South Germany. Springer Plus. 2016; 5: 1-8.

- Wasi?ski B, Sroka J, Wójcik-Fatla A, Zaj?c V, Cisak E, Knap JP, et al. Seroprevalence of leptospirosis in rural populations inhabiting areas exposed and not exposed to floods in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012; 19: 285-288.

- Garba B, Bahaman AR, Bejo SK, Zakaria Z, Mutalib AR, Bande F. Major epidemiological factors associated with leptospirosis in Malaysia. Acta Trop. 2018; 178: 242-247.

- Picardeau M. Leptospirosis: updating the global picture of an emerging neglected disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015; 9: e0004039.

- Costa F, Hagan JE, Calcagno J, Kane M, Torgerson P, Martinez-Silveira MS, et al. Global morbidity and mortality of leptospirosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015; 9: e0003898.

- Hartskeerl RA, Collares-Pereira M, Ellis WA. Emergence, control and re-emerging leptospirosis: dynamics of infection in the changing world. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011; 17: 494-501.

- Picardeau M. Diagnosis and epidemiology of leptospirosis. Méd Mal Infect. 2013; 43: 1-9.

- Sohail ML, Khan MS, Ijaz M, Naseer O, Fatima Z, Ahmad AS, et al. Seroprevalence and risk factor analysis of human leptospirosis in distinct climatic regions of Pakistan. Acta Trop. 2018; 181: 79-83.

- Ali E, Abazaj E, Hysaj B. Leptospirosis an increase disease in Albania. Int J Sci Res. 2015; 4: 8-11.

- Jansen A, Stark K, Schneider T, Schöneberg I. Sex differences in clinical leptospirosis in Germany: 1997-2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 44: e69-72.

- Agampodi SB, Matthias MA, Moreno AC, Vinetz JM. Utility of quantitative polymerase chain reaction in leptospirosis diagnosis: association of level of leptospiremia and clinical manifestations in Sri Lanka. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54: 1249-1255.

- Guerrier G, Hie P, Gourinat AC, Huguon E, Polfrit Y, Goarant C, et al. Association between age and severity to leptospirosis in children. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013; 7: e2436.

- Jansen A, Schöneberg I, Frank C, Alpers K, Schneider T, Stark K. Leptospirosis in Germany, 1962-2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005; 11:1048.

- Goris MGA, Boer KR, Duarte TATE, Kliffen SJ, Hartskeerl RA. Human leptospirosis trends, the Netherlands, 1925-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013; 19: 371-378.

- Alvarado-Esquivel C, Sánchez-Anguiano LF, Hernández-Tinoco J.Seroepidemiology of Leptospira exposure in general population in rural Durango, Mexico. BioMed Res Int. 2015; 2015: 460578.

- Agampodi SB, Peacock SJ, Thevanesam V, Nugegoda DB, Smythe L, Thaipadungpanit J, et al. Leptospirosis outbreak in Sri Lanka in 2008: lessons for assessing the global burden of disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011; 85: 471-478.

- Brockmann SO, Ulrich L, Piechotowski I, Wagner-Wiening C, Nöckler K, Mayer-Scholl A, et al. Risk factors for human Leptospira seropositivity in South Germany. SpringerPlus. 2016; 5: 1796.

- Calvopiña M, Vásconez E, Coral-Almeida M, Romero-Alvarez D, Garcia- Bereguiain MA, Orlando A. Leptospirosis: Morbidity, mortality, and spatial distribution of hospitalized cases in Ecuador. A nationwide study 2000-2020. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2022; 16: e0010430.

- Kawaguchi L, Sengkeopraseuth B, Tsuyuoka R, Koizumi N, Akashi H, Vongphrachanh P, et al. Seroprevalence of leptospirosis and risk factor analysis in flood-prone rural areas in Lao PDR. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008; 78: 957-961.

- Skufca J, Arima Y. Sex, gender and emerging infectious disease surveillance: a leptospirosis case study. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2012; 3: 37-39.

- Giefing-Kröll C, Berger P, Lepperdinger G, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. How sex and age affect immune responses, susceptibility to infections, and response to vaccination. Aging Cell. 2015; 14: 309-321.

- Brockmann SO, Ulrich L, Piechotowski I, Wagner-Wiening C, Nöckler K, Mayer-Scholl A, et al. Risk factors for human Leptospira seropositivity in South Germany, Springerplus. 2016; 5: 1796.

- Puca E, Pilaca A, Kalo T, Pipero P, Bino S, Hysenaj Z, et al. Ocular and cutaneous manifestation of leptospirosis acquired in Albania: A retrospective analysis with implications for travel medicine. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016; 14: 143-147.

- Rogers B, Brown J, Allen DG, Casey W, Clippinger AJ. Replacement of in vivo leptospirosis vaccine potency testing in the United States. Biologicals. 2022; 78: 36-44.

- Toliver HL, Krane NK, Lopez FA. Leptospirosis in New Orleans. Am J Med Sci. 2014; 347: 159-163.

- Lau CL, Watson CH, Lowry JH, David MC, Craig SB, Wynwood SJ, ET AL. Human leptospirosis infection in Fiji: an eco-epidemiological approach to identifying risk factors and environmental drivers for transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016; 10: e0004405.

- Haake DA, Levett PN. Leptospirosis in humans. Curr Top. Microbiol Immunol. 2015; 387: 65-97.

- Tomizawa R, Sugiyama H, Sato R, Ohnishi M, Koizumi N. Male-specific pulmonary hemorrhage and cytokine gene expression in golden hamster in early-phase Leptospira interrogans serovar Hebdomadis infection. Microb Pathog. 2017; 111: 33-40.