Primary Erectile Dysfunction Caused by Cavernovenous Leakage: Clinical Presentation and New Surgical Treatment in 91 Consecutive Patients

- 1. Clinique Geoffroy Saint Hilaire, Vascular Surgery Unit, France

- 2. CETI, 8 rue de Duras, France

- 3. CRID, 13 Avenue de l’Opéra, France

Abstract

Background: Primary erectile dysfunction (PED), characterized by its early-onset often results from cavernovenous leakage (CVL) in which blood prematurely returns from cavernosa to general circulation, impeding penile rigidity. Previous notions suggested CVL’s incurability.

Objectives: To describe symptoms and profile of PED patients with CVL, their penile hemodynamic profile and response to a new surgical treatment. A comparison is made with secondary ED (SED) patients.

Patients and methods: Prospective data from PED and SED patients were analyzed. Penile duplex sonography, computed caverno-tomography were performed. The treatment combined vein ligation and embolization during the same procedure.

Results: Ninety-one patients out of 171 (53.2%) had PED, with an average age of onset at 20.1 years vs. 47.4 in SED. PED patients exhibited severe ED symptoms and had waited 14.2 years before surgery. 14.3% PED patients had a mild neurological impairment, hormonal abnormalities were rare, exposure to cardiovascular risk factors was low, in contrast to SED patients, except for smoking. Combined surgery showed an 80.2% success rate, with improvements in hemodynamic parameters at three-month control duplex sonography. The proportion of PED patients with a pharmacologic EHS<3 with no possible penetration dropped from 63.7 to 13.2% after surgery (Chi-2: p<001). After a mean 25.4 months follow-up, IIEF5 score increased from 10.73 to 14.9 in PED patients (p<0001). The success rates of the combined surgery were comparable between the two groups, except that 45.2% PED patients did not use any ED medical treatment after successful surgery, vs. 20.9% in SED (p=024).

Conclusions: This study challenges the notion of PED due to CVL as incurable and highlights the efficacy of a novel treatment approach combining open surgery and embolization. Patients with successful treatment showed improved erectile function and reduced reliance on medication. The findings suggest the importance of early detection of CVL in PED.

Keywords

• Primary Erectile Dysfunction

• Erectile dysfunction

• Cavernovenous leakage

• Venous leakage

• Treatment

• Surgery

• Embolization

• Penile Duplex sonograph

CITATION

Allaire E, Sussman H, Hauet P, Floresco J, Crul C, et al. (2024) Primary Erectile Dysfunction Caused by Cavernovenous Leakage: Clinical Presentation and New Surgical Treatment in 91 Consecutive Patients. JSM Sexual Med 8(1): 1132.

INTRODUCTION

Primary erectile dysfunction (PED) is defined by its early onset in erectile life [1,2]. Its most frequent cause is cavernovenous leakage (CVL) [3]. In this condition, blood entering into the cavernosa returns to the general circulation too early, preventing pressure to raise in the penis [4-8]. First described in bull [9], CVL causes difficulties or impossibility to trigger or maintain erections. It has been proposed that CVL results from malformative venous defects or alterations of the albuginea and its function of locking emissary veins [4,5,10]. In severe forms, the increase of arterial inflow by phospho-diesterase 5-inhibitors (PDE5-Is) or other pro-erectile drugs [11] ,fails to compensate for uncontrolled venous outflow. Despite publications from the pre-Viagra era [12,13], and later from G. Hsu et al. [14], CVLs are considered incurable [15]. Penile prosthesis implantation in young men raises reluctances. Personal and social consequences in young men left with no treatment are devastating. Recovering their physiologic erections is the request from most patients suffering PED and CVL.

Our aim was to provide a description of symptoms and hemodynamic profile of patients with PED caused by CVL, assess their response to a new treatment scheme combining vein ligation open surgery and embolization during the same procedure [16], and compare these data to that of patients with secondary ED (SED) treated similarly for CVL.

METHODS

We analyzed prospectively collected data from consecutive patients referred to our outpatient care facility (CETI) and operated-on for CVL, with age of ED onset less or equal to 30 years (PED Group), and compared them to those of patients with CVL who experienced ED onset after 30 years (SED Groupe). Patients were assessed for cardiovascular risk factors, erectile symptoms, penile hemodynamic profile and response to pharmacologic stimulation, penile electromyography (P-EMG) if a neurological disease was suspected, and hormonal evaluation if a defect was suspected clinically, and in patients aged over 40.

Pharmacologically-challenged Penile Duplex Sonography (PC-PDS)

Vein-centered PC-PDS was perfomed as previouly decribed [17], for CVL diagnosis and three months after surgery for quality control. Briefly, an intracavernosal injection (ICI) was performed with Alprostadil (UCB Pharma, Colombes, France), Papaverine (Renaudin Laboratory, Itxassou, France), Urapidil (Takeda France, La Défense, France), Verapamil (Ratiopharm, Ulm, Germany), Atropine (Aguettant, Lyon, France) and Dipyridamole (Boehringer Ingelheim, Vienna, Austria), replaced since March 2020 by Papaverine and Prostaglandin E1 (CSP, Cournon d’Auvergne, France). The Erection Hardness Score (EHS) [18], was used to assessed response to ICI (PC-EHS) and for clinical follow-up evaluation. Venous flow was assessed by Deep Dorsal Vein Velocity (DDVV) and Superficial Vein Velocity (SVVs) recording. End Diastolic Velocity (EDV) was recorded on cavernosal arteries.

Pharmacologically-Challenged Computed Caverno- Tomography (PC-CCT)

After CVL diagnosis by PC-PDS, a PC-CCT was performed as already described [19], with a 64-row computerized tomographic scanner (Siemens France, Saint Denis, France) after ICI of the same pharmacologic mix as for PC-PDS, and ICI of Iopamiron 370 (Bracco Imaging, France). Images were processed in Volume Rendering Display and displayed on the VizuaOline platform (Vizua, Paris, France).

Penile Electromyography (P-EMG)

P-EMG used a Medtronic Keypoint Unit (Boulogne Billancourt, France), recording: 1. bulbo-cavernous reflex latency, length and profile, 2. penis dorsal sensitive nerve conduction, 3. somatosensory-evoked potentials [20]. Classification was as follows: N0: normal, N1: deviation above two standard deviations on one nerve, N2 on two nerves, N3 on three, N4 no response.

Criteria for surgery

Indication was ED lasting for more than six months, evidence of CVL on PC-PDS and PC-CCT. Penile prosthesis implantation was presented as an option to patients over 40, and discussed with all. Exclusion criteria for CVL surgery were: any other untreated somatic cause of ED, including significant alteration of penile arterial inflow, EMG score N>2, significant penile curvature, psychiatric disorder, anticipated poor compliance to follow-up, and for embolization, personal or familial history of thrombo- embolic event or prothrombotic factors abnormality. All patients had signed an informed consent before surgery.

Surgical procedure

Surgery associating vein ligation and embolization during the same procedure under general anesthesia has been presented previously [16]. It aimes at occluding all identified leaks. Embolization was performed with 3% Lauromacrogol 400 (Kreussler Pharma, Roissy, France) in Trendelenburg’s position during a Valsalva maneuver [21]. Incisions were performed in the pubic area, on the penis dorsum, or for a complete access to the pendulous penis by an inside-out (degloving) maneuver [14], according to CVL location. At the end of the procedure, an ICI of Papaverine and contrast medium was performed for control, and remaining leaks were treated. Patients received Enoxaparin 4000 IU daily for one week postoperatively.

Postoperative evaluation and follow-up

Penile hemodynamic and EHS in response to IC pharmacologic stimulation were re-assessed three months post-operatively by a control PC-PDS. Patients were interviewed using the EHS scale for morning erections, masturbation and sexual intercourses, before surgery, and during follow-up. If required, a second PC- CCT and complementary surgery were proposed.

Success definition

The composite success criterium was as follows: 1. If pre- operative PC-EHS was <3, post-operative PC-EHS ≥ 3.0 defined success (.5 EHS increment), 2. If pre-operative PC-EHS was ≥ 3, an EHS score increase ≥ 5 defined success. 3. If pre-operative EHS was 4 with disabling erection instability, a 4 post-operative PC- EHS and erection stability defined success.

Endpoints

Primary endpoints were: 1. Composite success rate, 2. Three-month PC-EHS.

Secondary endpoints were: 1. Pre- and post-operative PC- PDS-assessed hemodynamic parameters, 2. Clinical parameters: follow-up EHS and percentage of penetration during intercourses.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Pre-operative and three-month post-operative quantitative parameters were compared using a paired Student t-test. Comparisons of continuous variables between groups used a T-test of means. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed with a χ2 test. p<05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Pre-operative intergroup comparisons

Ninety-one among 171 consecutive patients (53.2%) who underwent CVL surgery from may 2016 to march 2023 had experienced ED onset before or at 30 years, and were accordingly identified as PED patients. Fifty-five (56%) of the 91 PED patients had experienced ED onset at or younger than 20.

Table 1 details patient characteristics.

Table 1: Patient characteristics

|

Patient characteristics |

Primary – Age (N=91) |

Secondary (N=80) |

p |

|

Mean age at ED onset (years) {range} |

20.1 ± 4.9 {13-30} |

47.4 ± 10.0 {31-70} |

<.0001* |

|

Symptom duration before surgery (years) |

14.2 ± 9.3 |

7.0 ± 6.3 |

<.0001* |

|

Age at surgery (years) |

34.3 ± 8.9 |

54.4 ± 9.6 |

<.0001* |

|

Patients with penile EMG abnormalities (score N≤2) (%) |

14.3 |

32.5 |

.025** |

|

Patients with mild arterial disease detected by PC-PDS (%) |

.01 |

20.0 |

<.001** |

|

Patients with hypotestosteronemia (%) |

.02 |

16.2 |

.003** |

|

Cardiovascular risk factors (%) |

|

|

|

|

Diabetes (%) |

.02 |

25.0 |

<.001** |

|

Tobacco (%) |

22.0 |

21.2 |

.93** |

|

Hypertension (%) |

.02 |

11.2 |

.024** |

|

Hyperlipidemia (%) |

.04 |

13.7 |

.049** |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. EMG: electromyography. PC-PDS: Pharmacologically challenged penile duplex sonography. *: T-test of means; **: CHI- 2 test.

Mean age of PED patients at ED onset was 20.1 ± 4.9 years, and 47.4 ± 10.0 in SED patients (p<0001). Mean ED duration before surgery was 14.2 ± 9.3 years in PED patients, the longest delay being 30 years, compared to 7.0±6.3 years in SED patients (p<0001). Mean age at surgery was 34.3 ± 8.9 and 54.4 ± 9.6 years, in PED and SED patients, respectively (p<0001). Additional causes of ED identified during pre-operative arterial and hormonal work-up were rare in PED, in contrast to SED (Table 1). 14.3% of PED patients had a mild neurological defect. Prevalence of hypertension and hyperlipidemia was low in PED patients. Tabaco use was similar in both groups (Table 1). Pre-operative Erection Hardness Scores during the three circumstances of erectile life, i.e. morning, masturbation and intercourses, were similar in both groups (p>.05) (Table 2),

Table 2: Pre-operative and end-of-follow-up clinical erectile function

|

Primary |

Pre-operative |

Post-operative |

p |

|

Mornings with erection per week (N) |

1.26 ± 1.68 |

3.2 ± 2.7 |

<.0001 |

|

Mean morning EHS |

1.05 ± 1.38 |

2.15 ± 1.48 |

<.0001 |

|

Masturbation EHS |

2.11 ±83 |

3.10 ± 0.75 |

<.0001 |

|

Intercourse EHS |

1.95 ± 68 |

3.33 ± 0.69 |

<.0001 |

|

Intercourse penetration (%) |

17.7 ± 27.7 |

64.2 ± 39.0 |

<.0001 |

|

Erection stability (%) |

0 |

31.9 |

<.001 |

|

IIEF-5 |

8.97±5.13 |

16.0 ± 5.6 |

<.0001 |

|

Secondary |

Pre-operative |

Post-operative |

p |

|

Mornings with erection per week (N) |

1.37 ± 2.23 |

2.8 ± 2.4 |

<.0001 |

|

Mean morning EHS |

85 ± 1.09 |

2.09 ± 1.24 |

<.0001 |

|

Masturbation EHS |

2.12 ± 67 |

2.95 ± 0.74 |

<.0001 |

|

Intercourse EHS |

1.92± 63 |

3.30 ± 0.66 |

<.0001 |

|

Intercourse penetration (%) |

23.3± 33.7 |

76.6 ± 35.4 |

<.0001 |

|

Erection stability (%) |

0 |

33.7 |

<.001 |

|

IIEF-5 |

10.73 ± 5.02 |

14.9 ± 6.4 |

<.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentage; EHS: Erection Hardness Score. *: Student paired t-test. ** Chi-2 test. IIEF-5: International Index of Erectile Function, domaine 5 score.

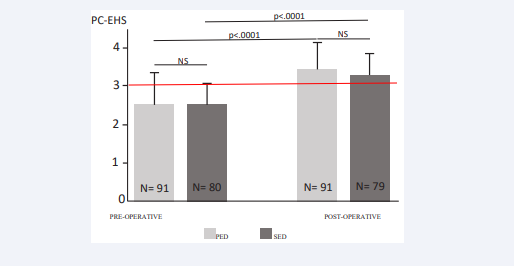

as were pre-operative mean International Index of Erectile Function, domain 5 score (IIEF-5) (8.97±5.13 and 10.73±5.02 in PED and SED patients, respectively, p=75), mean pre-operative PC-EHS (2.55 ± 75 and 2.56 ± 54 in PED and SED groups, respectively, p=89) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pre- and post-operative EHS after intracavernous pharmacologic stimulation. PED: primary erectile dysfunction. SED: secondary erectile dysfunction. PC-EHS: Pharmacologically- challenged Erection Hardness Score. N: number of patients. P: Student paired t-test.

The proportion of patients with pre-operative PC-EHS less than 3, accordingly with no penetration possibility despite strong pharmacological support, was 36.3 in PED, and 33.7 in SED (P=81). All patients reported disabling erection instability during intercourses and masturbation.

Penile hemodynamic PC-PDS parameters are presented in Table 3. Pre-operative End Diastolic Velocity (EDV) was significantly lower in PED than in SED group (p=007). Other parameters (Deep Dorsal Vein Velocity (DDVV)), Superficial Vein Velocity (SVV), did not differ significantly.

Table 3: Penile hemodynamic parameters changes upon surgery

|

Primary |

Pre-operative |

Post-operative |

p* |

|

EDV (cm/s) |

9.6 ± 8.7 |

6.9 ± 2.0 |

.027 |

|

DDVV (cm/s) |

10.9 ± 12.0 |

0.6 ± 1.7 |

.0001 |

|

SVV (cm/s) |

11.2 ± 10.5 |

4.5 ± 1.5 |

.0001 |

|

Secondary |

Pre-operative |

Post-operative |

p* |

|

EDV (cm/s) |

13.6 ± 8.7 |

9.9 ± 1.8 |

.0001 |

|

DDVV (cm/s) |

13.3 ± 13.7 |

0.9 ± 0,9 |

.0001 |

|

SVV (cm/s) |

10.5 ± 8.2 |

4.6 ±1.6 |

.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. DDVV: Deep Dorsal Vein Velocity; EDV: End Diastolic Velocity; SVV: superficial vein velocity. *: Student paired t-test.

Operative and post-operative course

Both ligation open surgery and embolization were performed during the same procedure in 80.2% and 92.2% of PED and SED patients, respectively (p=0.53). Embolization as only treatment was possible in only 5.3% patients, because of venous leak location. One patient committed suicide seven weeks after surgery in the SED group, after he was told by another surgeon his surgery was a failure, although end-of-surgery cavernography had shown complete leakage resolution. Reoperations were performed in 11.0% and 17.5% of patients in PED and SED groups, respectively (p=29) for venous leaks persisting at three- month control PC-PDS. When patients underwent a second CVL intervention, data from PC-PDS and clinical evaluation after the last surgery were used for analysis.

Three-month post-operative erectile response to ICC pharmacologic stimulation

All patients alive had a control PC-PDS three to five months post-operatively. Upon surgery, mean PC-EHS had increased significantly in PED patients, from 2.55±75 to 3.47±60, similarly as in SED patients (from 2.56±54 to 3.31±50) (paired t-test: p<.0001 in both groups) (Figure 1). Post operative PC-EHS did not differ between groups (t-Test of means: p=089), neither mean PC-EHS increases (89±91 and 72±52 in PED and SED groups, respectively, t-Test of means: p=131). The proportion of patients with a PC-EHS<3 with no possible penetration, dropped from 63.7 to 13.2% after surgery in PED (Chi-2 test: p<001) and from 66.3 to 10.4% in SED group (Chi-2 test: p<001), with no difference between groups: p=87). According to the composite criterium, surgery was successful in 80.2 and 83.7% in PED and SED patients, respectively (p=64).

Three-month post-operative hemodynamic assessment

All three hemodynamic parameters had improved significantly after surgery in the two groups (Table 3), with no intergroup statistical difference (data not shown).

Erectile function at the end of follow-up

Mean follow-up was 25.4±21.2 and 19.5±17.5 months in PED and SED groups, respectively (p=067). Eight patients are waiting for PC-CCT and a second intervention. Six patients in the SED group (6.6%) had a penile prosthesis implantation, with no technical difficulty reported by urologists. The youngest were 21, 22 and 23 years old, and eventually reported a satisfactory sexual life. Their end-of-follow-up time was that of implantation decision. Functional clinical results at the end of follow-up are presented in Table 2. All clinical parameters of erection had increased significantly (p<0001) in PED as well as in SED patients, with no difference between groups, except for intercourse penetration success rate that tented to be lower in PED than in SED patients (64.2±39.0 vs. 76.6±35.4, p=066). The number of patients with stable erections raised from zero pre-operatively in both groups, to 31.9 and 33.7% in PED and SED groups, respectively (comparison of post- to pre-operative stability: Chi-2 test: p<001in each group, p=928 between groups). At the end of follow-up, among PED patients with successful CVL surgery, 45.2% did not use any ED medical treatment (after exclusion of those with a penile implant), significantly more than in SED patients (20.9%, p=024 between groups). Those patients had similar three-month hemodynamic parameters at control PC-PDS (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This series of 91 patients with CVL and PED resistant to PED5-Is provides a new insight into the fate of patients with PED. PED patients were younger at surgery than SED patients, but had awaited as long as 14 years before CVL diagnosis and treatment. Their ED symptoms were as severe as those of SED patients. They had a low exposure to cardiovascular risk factors except for smoking, and low rates of associated arterial and endocrine causes of ED in addition to CVL, with the exception of neurologic impairment. Lastly, PED hemodynamic was characterized by lower EDV than SED patients. We demonstrate an 80.2% success rate of combined open and endovascular CVL surgery in PED caused by CVL. Half PED patients with successful treatment were not using any medication for sexual intercourse at the end of the two-year follow-up.

Steifer et al., have restricted PED definition to onset of ED at the adolescence [1]. Fifty-seven of our 171 patients (62.2%) had experienced ED before the age of 21. The rest of them had discovered after their adolescence and 20, at time of first sexual intercourse. From our experience, we believe that the 20-year cut-off excludes many patients who had weak erections since the beginning of their sexual life, without being aware of their symptoms. In addition, patients with the 30-year cut-off share lack of a significant sexual experience prior to disease onset, in contrast to patients who experienced ED after 30. Lastly, we did not find statistical differences between patients with ED onset before the age of 21 (57 patients) or 31 (91 patients), for any pre-or post-operative parameters (data not shown). Accordingly, the 30-year cut-off appeared to be more relevant for defining a homogenous group referred to as PED.

Information on ED in young men is limited, with important variability in methodology [22], and results. The proportion of men under 40 seeking medical advises for ED has increased in recent years [23,24], a demonstration of the increasing concern for their condition. The reported prevalence of ED in men under 40 varies from one to 10% [23]. The prevalence of somatic causes of ED under 40 also varies widely, between 17 to 85%, with CVL representing between 1,7 [25], to 52% of all somatic causes [1,26,27], Aboseif, Wetterauer et al., 1990 (reviewed in [2]. These wild variations raises questions about CVL diagnosis reliability. The diagnosis of CVL by PC-PDS in younger men may be hampered by false positives because of sympathetic over- stimulation by stress [28], with potential overestimation of CVL rates. Earlier publications however used penile flowmetry in addition to PC-PDS, with high reliability for CVL diagnosis. In order to obviate false positives [29], we used a high level of pharmacologic stimulation both for PC-PDS and PC-CCT [17]. PED patients in our series had severe ED with a mean 8.97 IIEF-5 score, and were unresponsive to PDE5-Is, as are half of patients with CVL [3]. With due limitations, it can be proposed that men with ED resistant to PDE5-Is caused by CVL represent at least one to two percent of the male population under 30. Accordingly, CVL causing disabling ED is a frequent situation.

Associated causes of ED in our PED patients were mostly neurologic. Hormonal or arterial associated causes were exceptional, in contrast to the SED population, as observed by others [2]. Low testosterone is rarely a cause of ED in young men [30]. Similarly, exposure to cardiovascular risk factors was less in PED than in SED patients, except for tobacco use. The low prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors is likely related to the younger age of PED patients at time of surgery. The percentage of smokers in our PED patients was similar to that of tobacco use before the age of 25 worldwide [31]. CVL is a venous, not an arterial disease, with contribution of cardiovascular risk factors in young patients.

Despite the fact that ED was not more severe in PED than in SED operated patients, their experience of ED was devastating. The mean age at first sexual intercourse is 18 [32]. The mean age at CVL surgery in our PED patients was 34. Accordingly, our patients had endured ED and sexual failure for half of their live before CVL diagnosis and treatment. This delay may be due to different factors. It has been proposed that men under 40 are less likely to seek medical advice [33]. In addition, ED in younger patients may be less scrutinized by health care providers, because of the false idea that ED in young is mostly psychogenic [2]. Accordingly, CVL represents a public health concern as the main cause of invalidating ED affecting young men, with regard to its high prevalence and its devastating consequences [34].

Earlier attempts for treating CVL have been failures [35-39]. Neither surgery [13,40], nor embolization alone [41,42] can effectively control CVLs in most patients. In order to obviate poor results of earlier attempts, we have developed a procedure combining vein ligation open surgery and endovascular embolization, after pre-operative topographic assessment of CVLs using both vein-centered PC-PDS [17], and PC-CCT [19], with encouraging initial results [16]. Less than six percent of our patients could be treated by embolization alone. This is due to CVL topography and emphasize the role of multiple technic combinations in controlling CVLs. Systematic post-operative PC-PDS performed at a sufficient delay after surgery is critical for documenting procedure completeness as well as for patient reassurance. We believe that this rigorous approach contributed to the fact that half of our PED patients with successful surgery were able to enjoy a erectile and sexual life without the help of any medication.

PED and SED patients responded similarly well to our treatment protocol, on both hemodynamic and clinical criteria, with a 80% success rate on composite criterium at a two-year follow-up in the former group. PED patients used twice-less frequently PDE5-I inhibitors in the long run, than SED patients, albeit with a lower penetration success during intercourses (borderline statistical significance). Poorer intercourse performances in PED patients post-operatively may translate a lack of initial satisfactory sexual experience, heavier psychologic sequels of ED, and possibly a reluctance to use medications as a support against performance anxiety. We believe that a sexual and psychological support post-operatively would be beneficial to PED patients. Three young patients finally had a penile implant because of CVL surgery failure. Overall, PED patients have a particular personal history, contrasting to that of SED patients. They discover intercourse sexuality after a long and traumatizing experience of failure and denial from the medical community. More than other patients with ED, PED patients require a multidisciplinary approach, not only for treatment and diagnosis, but also for psychological and sexual reconstruction.

Our study presents some limitations. It is monocentric. Reproducibility needs to be assessed. Although we were able to document a two-year stability of erection recovery, further assessments of durability are awaited.

In conclusion, our large series provides new information to understand better the fate of patients with CVL and ED resistant to medical treatment when occurring early in sexual life. In this population with currently no treatment option, we demonstrate for the first time the efficacy of combined open and endovascular surgery, with a documented two-year durability. Considering the far-reaching consequences of ED in this population, we propose that CVL should be detected in PED, and combined surgery discussed with patients in selected centers.

AKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Sylvain Ordureau for providing access to Vizua Online plate-form for Computed Caverno-Tomography images processing, and Marjory Arnion for helping collecting data prospectively.

REFERENCES

- Stief CG, Bähren W, Scherb W, Gall H. Primary erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 1989; 141: 315-319.

- Ludwig W, Phillips M. Organic causes of erectile dysfunction in men under 40. Urol Int. 2014; 92: 1-6.

- Wespes E, Rammal A, Garbar C. Sildenafil non-responders: haemodynamic and morphometric studies. Eur Urol. 2005; 48: 136-139.

- Hsu GL. Hypothesis of human penile anatomy, erection hemodynamics and their clinical applications. Asian J Androl. 2006; 8: 225-234.

- Hsu GL, Yi-Ping Hung, Mang-Hung Tsai, Cheng-Hsing Hsieh, Heng- Shuen Chen, Eugen Molodysky, et al. Penile veins are the principal component in erectile rigidity: a study of penile venous stripping on defrosted human cadavers. J Androl. 2012; 33: 1176-1185.

- Wespes E, Schulman CC. Venous leakage: surgical treatment of acurable cause of impotence. J Urol. 1985; 133: 796-798.

- Delcour C, Wespes E, Vandenbosch G, Schulman CC, Struyven J. Impotence: evaluation with cavernosography. Radiology. 1986; 161: 803-806.

- Hsieh CH, Chii-Jye Wang, Geng-Long Hsu, Shyh-Chyan Chen, Pei- Ying Ling, Tsu Wang. Penile veins play a pivotal role in erection: the haemodynamic evidence. Int J Androl. 2005; 28: 88-92.

- Young SL, Hudson RS, Walker DF. Impotence in bulls due to vascular shunts from the corpus cavernosum penis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1977; 171: 643-648.

- Shafik A, Ismail Shafik, Olfat El Sibai, Ali A Shafik. On the pathogenesis of penile venous leakage: role of the tunica albuginea. BMC Urol. 2007; 7: 14.

- Virag R. Intracavernous injection of papaverine for erectile failure. Lancet. 1982; 2: 938.

- Bar-Moshe O, Vandendris M. Surgical approach of venous leakage.Urol Int. 1992. 49: 19-23.

- Wespes E, Delcour C, Preserowitz L, Herbaut AG, Struyven J, SchulmanC. Impotence due to corporeal veno-occlusive dysfunction: long-termfollow-up of venous surgery. Eur Urol. 1992; 21: 115-119.

- Hsu GL, Heng-Shuen Chen, Cheng-Hsing Hsieh, Wen-Yuan Lee, Kuo- Liang Chen, Chao-Hsiang Chang. Clinical experience of a refined penile venous stripping surgery procedure for patients with erectile dysfunction: is it a viable option? J Androl. 2010. 31: 271-280.

- Salonia A, Carlo Bettocchi, Luca Boeri, Paolo Capogrosso, Joana Carvalho, Nusret Can Cilesiz, et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health-2021 Update: Male Sexual Dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2021. 80: 333-357.

- Allaire E, Hélène Sussman, Ahmed S Zugail, Pascal Hauet, Jean Floresco, Ronald Virag. Erectile Dysfunction Resistant to Medical Treatment Caused by Cavernovenous Leakage: An Innovative Surgical Approach Combining Pre-operative Work Up, Embolisation, and Open Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2021; 61: 510-517.

- Sussman H, Labastie MN, Hauet P, Allaire E, Lombion S, Virag R. Ultrasonography after pharmacological stimulation of erection for the diagnosis and therapeutic follow-up of erectile dysfunction due to cavernovenous leakage. J Med Vasc. 2020; 45: 3-12.

- Mulhall JP, Irwin Goldstein, Andrew G Bushmakin, Joseph C Cappelleri, Kyle Hvidsten. Validation of the erection hardness score. J Sex Med. 2007; 4: 1626-1634.

- Virag R, Paul JF. New classification of anomalous venous drainageusing caverno-computed tomography in men with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2011; 8: 1439-1444.

- Virseda-Chamorro M, Lopez-Garcia-Moreno AM, Salinas-Casado J, Esteban-Fuertes M. Usefulness of electromyography of the cavernous corpora (CC EMG) in the diagnosis of arterial erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2012; 24: 165-169.

- Herwig R, Sansalone S. Venous leakage treatment revisited: pelvic venoablation using aethoxysclerol under air block technique and Valsalva maneuver. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2015; 87: 1-4.

- Butaney M, Nannan Thirumavalavan, Mark S Hockenberry, Will Kirby E, Alexander W Pastuszak, Larry I Lipshultz. Variability in penile duplex ultrasound international practice patterns, technique, and interpretation: an anonymous survey of ISSM members. Int J Impot Res. 2018; 30: 237-242.

- Rastrelli G, Maggi M. Erectile dysfunction in fit and healthy young men: psychological or pathological? Transl Androl Urol. 2017; 6: 79- 90.

- Capogrosso P, Michele Colicchia, Eugenio Ventimiglia, Giulia Castagna, Maria Chiara Clementi, Nazareno Suardi. One patient out of four with newly diagnosed erectile dysfunction is a young man--worrisome picture from the everyday clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2013; 10: 1833-1841.

- Caskurlu T, Ali Ihsan Tasci, Sefa Resim, Tayfun Sahinkanat, Erbil Ergenekon. The etiology of erectile dysfunction and contributing factors in different age groups in Turkey. Int J Urol. 2004; 11: 525- 529.

- Karadeniz T, Medih Topsakal, Ahmet Aydogmus, Dogan Basak. Erectile dysfunction under age 40: etiology and role of contributing factors. ScientificWorldJournal. 2004; 4: 171-174.

- Donatucci CF, Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction in men under 40: etiology and treatment choice. Int J Impot Res. 1993; 5: 97-103.

- Shamloul R. Peak systolic velocities may be falsely low in young patients with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2006; 3: 138-143.

- Ravikanth R. Diagnostic categorization of erectile dysfunction using duplex color doppler ultrasonography and significance of phentolamine redosing in abolishing false diagnosis of venous leak impotence: A single center experience. Ind J Radiol Imaging. 2020; 30: 344-353.

- Zhuravleva ZD, Johansson A, Jern P. Erectile Dysfunction in Young Men: Testosterone, Androgenic Polymorphisms, and Comorbidity With Premature Ejaculation Symptoms. J Sex Med. 2021; 18: 265- 274.

- Reitsma MB, Luisa S Flor, Erin C Mullany, Vin Gupta, Simon I Hay, Emmanuela Gakidou. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and initiation among young people in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019. Lancet Public Health. 2021; 6: e472-e481.

- Fischer N, Traeen B, Samuelsen SO. Sexual Debut Ages in Heterosexual Norwegians Across Six Birth Cohorts. Sex Cult. 2023; 27: 916-929.

- Shabsigh R, Michael A Perelman, Edward O Laumann, Daniel C Lockhart. Drivers and barriers to seeking treatment for erectile dysfunction: a comparison of six countries. BJU Int. 2004; 94: 1055- 1065.

- Tal R, Bryan B Voelzke, Spencer Land, Pejman Motarjem, Ricardo Munarriz, Irwin Goldstein, et al. Vasculogenic erectile dysfunction in teenagers: a 5-year multi-institutional experience. BJU Int. 2009; 103: 646-650.

- Nakata M, Takashima S, Kaminou T, Koda Y, Morimoto A, HamuroM, et al. Embolotherapy for venous impotence: use of ethanol. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000; 11: 1053-7.

- Courtheoux P, Maiza D, Henriet JP, Vaislic CD, Evrard C, TheronJ. Erectile dysfunction caused by venous leakage: treatment with detachable balloons and coils. Radiology. 1986; 161: 807-809.

- Moriel EZ, Mehringer CM, Schwartz M, Rajfer J. Pulmonary migration of coils inserted for treatment of erectile dysfunction caused by venous leakage. J Urol. 1993; 149: 1316-1318.

- Virag R, Bennett AH. Arterial and venous surgery for vasculogenic impotence: a combined French and American experience. Arch Ital Urol Nefrol Androl. 1991; 63: 95-100.

- Rebonato A, Alessio Auci, Franco Sanguinetti, Daniele Maiettini, Michele Rossi, Luca Brunese, et al. Embolization of the periprostatic venous plexus for erectile dysfunction resulting from venous leakage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014; 25: 866-872.

- Vale JA, Feneley MR, Lees WR, Kirby RS. Venous leak surgery: long- term follow-up of patients undergoing excision and ligation of the deep dorsal vein of the penis. Br J Urol. 1995; 76: 192-195.

- Peskircioglu L, Tekin I, Boyvat F, Karabulut A, Ozkarde? H. Embolization of the deep dorsal vein for the treatment of erectile impotence due to veno-occlusive dysfunction. J Urol. 2000; 163: 472- 475.

- Schild HH, Müller SC, Mildenberger P, Strunk H, Kaltenborn H, Kersjes W, et al. Percutaneous penile venoablation for treatment of impotence. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1993; 16: 280-286.