Ruptured Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy in a Patient with a Unicornuate Uterus and Contralateral Tubal Agenesis A Case Report

- 1. OBGYN Specialist, Al Ittihad Hospital, Palestine

- 2. Intern Doctor, Jenin Governmental Hospital, Palestine

- 3. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, An-Najah National University, Palestine

Abstract

Background: Ovarian ectopic pregnancy is a rare form of extrauterine gestation, accounting for less than 3% of all ectopic pregnancies. Its occurrence in the context of a unicornuate uterus and absent fallopian tube is exceedingly uncommon and presents a diagnostic challenge.

Case Presentation: We describe a case of a 26-year-old Palestinian woman with a known right-sided unicornuate uterus who presented with acute lower abdominal pain and elevated serum β-HCG. Transabdominal ultrasound revealed an empty uterus and a complex adnexal mass. Diagnostic laparoscopy identified a ruptured left ovarian ectopic pregnancy with massive hemoperitoneum and complete absence of the left fallopian tube. The ectopic tissue was excised laparoscopically, preserving ovarian function. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis. The patient recovered uneventfully and was counseled regarding reproductive implications and follow-up imaging.

Conclusion: This case highlights a rare combination of a unicornuate uterus, contralateral ovarian ectopic pregnancy, and absent fallopian tube. It underscores the importance of considering ectopic pregnancy even in anatomically implausible scenarios and the role of transperitoneal sperm migration. Early surgical intervention remains critical in such complex presentations to ensure fertility preservation and reduce maternal risk.

Keywords

• Pregnancy

• Ovarian

• Ectopic

• Laparoscopy

• Case Report

Citation

Barqawi Y, Fuqha R, Eisheh SA (2025) Ruptured Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy in a Patient with a Unicornuate Uterus and Contralateral Tubal Agenesis: A Case Report. JSM Sexual Med 9(4): 1162.

ABBREVIATIONS

β-HCG: Beta-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin; TVUS: Transvaginal Ultrasound; HSG: Hysterosalpingography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PE: Physical Examination; ED: Emergency Department; OR: Operating Room; IU: Intrauterine; IUP: Intrauterine Pregnancy; EP: Ectopic Pregnancy; OP: Ovarian Pregnancy; LMP: Last Menstrual Period; BP: Blood Pressure; HR: Heart Rate; US: Ultrasound; G: Gravida; P: Para.

INTRODUCTION

Ectopic pregnancy remains a leading cause of first trimester maternal morbidity and mortality, affecting approximately 1–2% of pregnancies [1]. Among these, ovarian ectopic pregnancies are rare, constituting less than 3% of all ectopic gestations [2]. Diagnosis is often delayed due to their nonspecific presentation and rarity, particularly when coexisting with congenital uterine anomalies. A unicornuate uterus is a Müllerian anomaly resulting from incomplete development of one paramesonephric duct. It occurs in approximately 0.1% of women and is associated with increased risks of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and preterm delivery. The presence of a unicornuate uterus with a contralateral ovarian ectopic pregnancy, especially in the absence of a fallopian tube on the affected side, represents an extraordinary reproductive event. We present a rare and instructive case of a ruptured ovarian ectopic pregnancy on the side contralateral to a unicornuate uterus and in the absence of a fallopian tube. This case exemplifies the complexity of reproductive physiology, highlights the importance of early recognition, and underscores the role of surgical management in preserving fertility.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 26-year-old married Palestinian woman, gravida 2 para 0, presented to the emergency department with a one-day history of acute right lower quadrant abdominal pain. She reported a missed menstrual period but denied any vaginal discharge or urinary symptoms. Her menstrual cycles were previously regular, and she was not using any form of contraception. Her sexual activity was reported to be regular and without difficulty. Her obstetric history was notable for one prior first-trimester spontaneous abortion, which was not further evaluated or managed. She had no significant medical, surgical, or family history. Notably, the patient was a known case of a non communicating unicornuate uterus, previously diagnosed via hysterosalpingography during an infertility workup. On examination, the patient appeared alert but mildly distressed due to pain. Her vital signs showed borderline hypotension and tachycardia. Abdominal palpation revealed tenderness in the lower abdomen, most pronounced on the right side. Speculum examination revealed a healthy-looking cervix with minimal bleeding and no evidence of discharge. A bimanual pelvic examination elicited right-sided adnexal tenderness; the uterus was mobile, with no cervical motion tenderness or palpable vaginal septum, and no adnexal masses were appreciated.

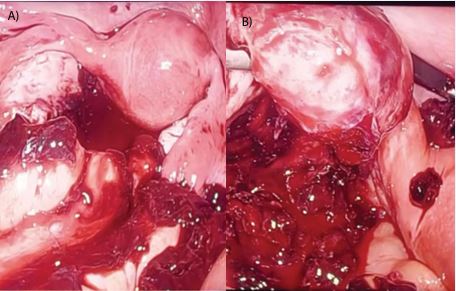

Initial laboratory workup demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 16.3 g/dL and a serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) level of 3,300 mIU/mL. Although the elevated hemoglobin level was unexpected in the context of suspected intra-abdominal bleeding, possible explanations include hemoconcentration, individual variation, or technical factors, as it was not repeated. Subsequently, a transvaginal ultrasound was conducted, revealing a right adnexal mass measuring approximately 5 cm with heterogeneous echotexture, suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy. The endometrium appeared thickened, measuring 18 mm, with an empty uterus, no visible gestational sac. Given the clinical presentation, sonographic findings, and rising β-HCG levels without evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy, a decision was made to proceed with diagnostic laparoscopy. Intraoperatively, approximately 1 liter of hemoperitoneum was discovered, primarily in the pouch of Douglas. The uterus was confirmed to be non-communicating unicornuate, with a single right-sided uterine horn. The right ovary and fallopian tube were grossly normal. Interestingly, the left fallopian tube was completely absent, and a ruptured ectopic pregnancy was identified on the surface of the left ovary. No rudimentary uterine horn, fibrous band, or abnormal communication between the horn and the contralateral side was noted. The ectopic gestational tissue was excised from the ovarian surface using bipolar cautery, preserving the ovarian tissue and achieving complete hemostasis, Figure 1a & 1b. The specimen was retrieved using an endobag, and no intraoperative or postoperative transfusion was required.

Figure 1 a: Intraoperative image showing a unicornuate uterus with surrounding hemoperitoneum, indicating significant intra-abdominal bleeding.

Figure 1b: The left ovary demonstrating active hemorrhage at the site of rupture, consistent with an ovarian ectopic pregnancy.

The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative recovery. On the first postoperative day, her β-HCG level had dropped to 900 mIU/mL, and she remained hemodynamically stable without signs of recurrent bleeding or infection. She was discharged home in good condition. Histopathological examination of the excised tissue confirmed the diagnosis of an ovarian ectopic pregnancy, with chorionic villi embedded within ovarian stroma. During follow-up, the patient was extensively counseled regarding the reproductive implications of a unicornuate uterus, including increased risks of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and preterm birth. Renal imaging was ordered, in line with guidelines due to the association between Müllerian anomalies and renal tract malformations. She was also advised to undergo early transvaginal ultrasound in future pregnancies to confirm intrauterine gestation promptly and reduce the risk of recurrence. At a two-week follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic, her β-HCG levels continued to decline appropriately, and pre-conception counseling and reproductive planning were initiated.

DISCUSSION

Ectopic pregnancy, defined as the implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the uterine cavity, most commonly in the fallopian tube, occurs in approximately 1–2% of all pregnancies and remains a significant contributor to first-trimester maternal morbidity and mortality [1]. Among these, ovarian ectopic pregnancies are extremely rare, accounting for less than 3% of ectopic cases, with an estimated incidence ranging from 1 in 7,000 to 1 in 40,000 live births [2,3]. A unicornuate uterus, which results from incomplete development of one Müllerian duct, is a rare congenital uterine anomaly occurring in roughly 0.1% of the general population [4]. This anomaly is associated with significant reproductive risks including miscarriage, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and a notably increased risk of ectopic pregnancy [5]. The coexistence of a unicornuate uterus and ovarian ectopic pregnancy, particularly in the absence of a fallopian tube on the side of implantation, is exceedingly rare and presents unique diagnostic and pathophysiologic challenges.

This case highlights the difficulty of diagnosing ectopic pregnancy in patients with atypical anatomy. The absence of an intrauterine gestation on ultrasound alongside elevated β-HCG and a complex adnexal mass raised suspicion. However, the presence of a unicornuate uterus and absent fallopian tube on the side of the ectopic implantation introduced a diagnostic paradox. Typically, fertilization and implantation occur on the side with an intact tubo-ovarian complex. Intraoperative findings confirmed a noncommunicating unicornuate uterus without a rudimentary horn or connecting fibrous band, thereby excluding the possibility of a rudimentary horn pregnancy. This anatomical configuration strongly supports transperitoneal sperm migration as the only feasible route for fertilization. The most plausible mechanism in this case is transperitoneal migration of spermatozoa from the patent right fallopian tube to the ovulating left ovary [6].Though uncommon, this phenomenon has been documented in reproductive literature. In fact, approximately one-third of pregnancies in women with a single functional tube are believed to result from such migration [7]. While transperitoneal ovum migration has been more widely described, sperm migration across the peritoneal cavity though, less studied, remains physiologically feasible.

Adding to the case’s uniqueness is the implantation site: the ovary. Ovarian ectopic pregnancy is among the least common implantation locations and poses diagnostic challenges due to its resemblance to hemorrhagic ovarian cysts or corpus luteum rupture on imaging. In the setting of a unicornuate uterus and absent ipsilateral tube, this makes preoperative diagnosis exceptionally difficult. A similar case reported by Connor et al. described an ovarian ectopic pregnancy contralateral to a unicornuate uterus; however, the affected side still had a present and patent fallopian tube. In our case, the complete absence of the tube strongly supports a direct fertilization mechanism independent of tubal transport [8]. The role of imaging in such patients is pivotal but limited. While transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the modality of choice in early pregnancy, and was performed in this case, revealing a right adnexal mass measuring 5 cm and a thickened endometrium of 18 mm, findings consistent with an ectopic pregnancy. Moreover, 2D ultrasound may not sufficiently delineate uterine anomalies. Advanced modalities such as 3D ultrasound or MRI improve anatomical clarity but were not feasible due to high coasts. This limitation highlights the importance of thorough gynecologic history and early imaging in at-risk individuals [9].

Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of ovarian ectopic pregnancy, particularly in ruptured or unstable cases. In our patient, prompt laparoscopy not only confirmed the rare diagnosis but enabled effective surgical management while preserving the ovary. Conservative laparoscopic resection is preferred to minimize damage to ovarian tissue, support fertility preservation, and reduce morbidity [9]. From a reproductive standpoint, patients with a unicornuate uterus face considerable risks including early miscarriage, cervical insufficiency, and recurrent ectopic pregnancy. The absence of one fallopian tube and an affected ovary further limits reproductive potential, making preconception counseling, renal imaging, and early pregnancy surveillance essential. Future pregnancies should be closely monitored with early first-trimester ultrasound to confirm intrauterine implantation and mitigate maternal risks.

CONCLUSION

This case presents a remarkable confluence of reproductive anomalies, an ovarian ectopic pregnancy on the side opposite a non-communicating ovary of unicornuate uterus, in the complete absence of a fallopian tube. It reinforces that even in anatomically restrictive settings, ectopic gestation remains a possibility due to mechanisms such as transperitoneal sperm migration. The case underscores the diagnostic difficulties posed by atypical anatomy and highlights the importance of early surgical intervention in preventing life-threatening complications and preserving reproductive function. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for ectopic pregnancy in patients with known uterine malformations, regardless of the anatomical constraints.

DECLARATIONS

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a single-patient case report and did not require institutional ethical approval. Informed consent was obtained from the patient, ensuring anonymity. This study conforms to the CARE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the efforts and time of the patient and her family.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally as co-first authors to the writing of this case report, provided feedback on earlier drafts, reviewed and approved the final manuscript, and agreed to its submission to the journal.

REFERENCES

- Vadakekut ES, Gnugnoli DM. Ectopic Pregnancy. Ncbi. 2025.

- Zahra LF, Badsi S, Benaouicha N, Zraidi N, Lakhdar A, Baydada A. Ovarian Ectopic Pregnancy: A Rare Entity of Extrauterine Pregnancy (A Case Report). Sch Int J Obstet Gynec. 2022; 6: 165-168.

- Bouab M, Touimi AB, Jalal M, Lamrissi A, Fichtali K, Bouhya S. Diagnosis and management of ectopic ovarian pregnancy: a rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022; 91: 106742.

- Garapati J, Jajoo S, Sharma S, Cherukuri S. Unicornuate Uterus with a Non-Communicating Rudimentary Horn: Challenges and Management of a Rare Pregnancy. Cureus. 2023; 15: e40666.

- Benlghazi A, Belouad M, Messaoudi H, Benali S, El Hassani MM, Kouach J. Spontaneous successful term delivery in a unicornuate uterus: A case report and literature review. 2023; 110: 108689.

- Mahé C, Zlotkowska AM, Reynaud K, Tsikis G, Mermillod P, Druart X, et al. Sperm migration, selection, survival, and fertilizing ability in the mammalian oviduct. 2021; 105: 317-331.

- Ziel HK, Paulson RJ. Contralateral corpus luteum in ectopic pregnancy: What does it tell us about ovum pickup?. Fertil Steril. 2002; 77: 850- 851.

- Connor VE, Huber J III W, Matteson AK. Ovarian ectopic pregnancy contralateral to unicornuate uterus. Clin Obstet Gynecol Reprod Med. 2015; 1: 66-67.

- Togas Tulandi. Fcahs Ectopic pregnancy: Clinical manifestations anddiagnosis. 2025.