The Anatomy of a Hybrid InPerson and Virtual Sexual Health Clinic in Oncology

- 1. Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, Canada

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Sexual health is compromised by the diagnosis and treatment of virtually all cancer types. Despite the prevalence and negative impact of sexual dysfunction, sexual health clinics are the exception in cancer centers worldwide. Consequently, there is an exigent need for effective, efficient, and inclusive sexual health programming in oncology. This paper describes the newly developed Princess Margaret Cancer Centers (Toronto, Canada) Sexual Health Clinic (SHC) utilizing an innovative, hybrid model of integrated in-person and virtual care. The SHC is dedicated to assisting patients/couples in re-establishing optimal sexual function, satisfaction, and interpersonal intimacy.

Materials and Methods: The SHC evolved from a fusion of the Prostate Cancer (Sexual) Rehabilitation Clinic at Princess Margaret (in-person) and the Movember TrueNorth Sexual Health And Rehabilitation e-Clinic (virtual) for prostate cancer patients. This hybrid care model was adapted to include six additional cancer sites (Cervical, Ovarian, Testicular, Bladder, Kidney, and Head and Neck) with plans to expand to all cancer sites. The SHC is theoretically founded in a biopsychosocial framework and emphasizes interdisciplinary intervention teams, active participation by the partner, and a broad-spectrum medical, psychological, and interpersonal approach. The launch of the SHC utilized a Hybrid Type 3 implementation methodology to ensure seamless integration into the patient workflows across the cancer sites of a high-volume cancer center.

Results and Discussion: The hybrid model of care has the potential to provide highly personalized care while conserving limited resources. Virtual visits are tailored to patients based on biological sex, cancer type, and treatment type. This process has resulted in 32 unique patient streams. The SHC virtual care is facilitated by highly trained sexual health counselors via chat, telephone, or videoconference. The sexual health counselors provide an additional layer of personalization and a “human touch” to the virtual clinic space. The in-person visits complement virtual care by providing comprehensive sexual health assessment and sexual medicine prescription. To inform quality assurance and evaluate effectiveness, relevant physical, psychological, and interpersonal outcomes will be serially collected via the SHC virtual portal over 12 months post-treatment. Additionally, analysis of 20 stakeholder interviews (HCP, clinic staff, and patients) will guide the SHC implementation into patient workflow.

Conclusion: The SHC is an innovative care model which has the potential to close the gap in sexual healthcare during a time of limited healthcare funds/resources. The SHC is designed as a transferable, stand-alone clinic which can be shared with cancer centers across North America.

KEYWORDS

Cancer, Sexual dysfunction, Biopsychosocial, Oncosexology.

CITATION

Matthew AG, Guirguis S, Incze T, Stragapede E, Peltz S, et al. (2022) The Anatomy of a Hybrid In-Person and Virtual Sexual Health Clinic in Oncology. JSM Sexual Med 6(5): 1102.

INTRODUCTION

Sexual health is compromised by the diagnosis and treatment of virtually all cancer types [1]. The nature of sexual dysfunction (SD) can differ by type of cancer and treatment, but invariably involve biological, psychological, and interpersonal factors that negatively affect the patient’s overall health-related quality of life [2]. Despite the gravity of SD and the associated psychosocial sequelae, sexual health clinics are the exception in cancer centers worldwide [3, 4]. This considerable gap in cancer care forms the basis for the need for sexual healthcare that is accessible and affordable without compromising effective personalized care delivery.

Prevalence and Severity of Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life

Impact on Physical Wellbeing: Over 50% of cancers diagnosed in Canada are breast and pelvic cancers [34] of these cancers, 30% of colorectal, 73% of breast, and 90% of prostate/

gynecological cancer survivors experience long-term SD. Additionally, 20% of non-breast/non-pelvic cancer survivors report SD that interferes with their overall quality of life. Ovarian and cervical cancer survivors report hot flashes, low desire, vaginal dryness, vaginal stenosis, atrophy, inflammation, discomfort, and pain during sex [4-6]. Patients undergoing treatment for prostate and testicular cancer can experience erectile dysfunction (ED), loss of desire, fatigue, hot flashes, and loss of satisfaction [2, 7, 8, 9]. In non-genitourinary cancers, such as head and neck cancers, loss of saliva, disfigurement, and fatigue can all have an impact on sexual health and patient quality of life [10].

Impact on Psychological Wellbeing: Although selected sexual side-effect profiles are short-term, the majority of survivors experience long-term sexual health concerns. The chronicity of the physical impact leaves patients vulnerable to psychological morbidity, including distress, depression, anxiety, and loss of self-esteem [11]. During cancer treatment, changes in body shape, scars, and hair loss can cause patients to feel less attractive or desirable and consequently experience less sexual desire themselves [12]. For some prostate cancer survivors, ED has been described as stripping them of their identity, sex life, and relationship [13]. Additionally, patients suffering from ED can experience performance anxiety which can interfere with adherence to pro-erectile therapy [14]. Impact on Interpersonal Wellbeing: Patients with SD report reductions in overall relationship intimacy and satisfaction [14]. Physical changes in sexual functioning can cause both male and female cancer survivors to avoid sexual intimacy with their partners. This behavior can lead to decreased relationship satisfaction which in turn can lead to further sexual dysfunction for the couple [14, 15]. In a study with cervical cancer survivors and their partners, many partners described that changes in sexual health after treatment (e.g., vaginal dryness; pain during intercourse; sexual dysfunctions) contributed to interpersonal problems and emotional distancing from their patient-partners [16].

Barriers to Sexual Healthcare in Oncology

Despite ongoing research and documentation of the physical, psychological and interpersonal burden of sexual dysfunction, the provision of sexual healthcare in oncology is uniformly inadequate. Research shows there are several barriers to sexual healthcare in cancer care including lack of practitioner-patient communication, care inequity, poor accessibility, and limited financial resources within healthcare institutions [17-19]. Practitioner-Patient Communication: Although clinicians recognize that sexual health is an important part of their patients’ quality of life, many report that they do not discuss sexual health with their patients [17]. Lack of communication between clinician and patient has been consistently identified as a barrier to accessing sexual healthcare [20]. The main barriers to practitioner-initiated conversations about sexual healthcare include a lack of time, resources, and appropriate training [17]. Specifically, it is believed that healthcare practitioners’ reluctance to engage in sexual health dialogue is due to their own discomfort in talking about sex, and feeling inadequate to assist patients due to the near absence of sexual health training in most medical schools [21-23]. Additionally, providers note subtle biases associated with patient-specific factors, such as age, cancer type, and curative treatment intent that can influence how or even if they discuss sexual health with their patients [20,17]. The absence of dialogue around sexual health can have a determinantal impact on patients who may interpret the absence as confirmation that SD is a normal part of treatment or something that must be endured [2]. It is important to note that the lack of communication is bidirectional. Patients can also contribute to this absence of practitioner-patient communication. Patients can feel ashamed of their SD and avoid talking about their concerns with their oncologists or assume that their oncology team is responsible solely for cancer-based medical treatment [21,22]. Even if a conversation does occur, the content and timing of the discussion may also influence its potential impact. It appears that brief and general discussions during oncology visits have limited impact on meeting the complex sexual health needs of oncology patients. Moreover, the timing of information and management

provision is also an important factor whereby some patients will benefit from early intervention [24]. While others may experience difficulties processing/retaining information during a time when cancer control is the primary focus [8,16]. Consequently, both early and ongoing inquiry combined with access to personalized care external to oncology visits is likely necessary to optimally treat sexual health concerns in an oncology setting.

Care Inequity: In healthcare, in general, marginalized populations are vulnerable to barriers to appropriate care, and these barriers may be amplified in relation to sexual health concerns. For the LGBTQ2+ community, cancer survivors report lower satisfaction with survivorship care [25]. These lower satisfaction rates can likely be explained by the prevalence of a heterosexist bias in medical care in North America combined with the lack of research and practitioner knowledge about the unique care needs of LGBTQ2+ cancer survivors [26]. Relatedly, practitioners can make inaccurate assumptions about a patient’s sexual orientation and/or gender identification that may unintentionally deter patients from voicing their sexual health concerns [27, 28]. Similarly, cultural inequities in healthcare are common given the strong cultural influence of Christianity on medical practice in most Western countries. Again, these barriers to appropriate care may be exacerbated in sexual healthcare given that sexual beliefs and practices are shaped by social and cultural factors [18]. Finally, ageism may also worsen barriers to sexual healthcare in the cancer survivorship setting. Practitioners may experience greater discomfort in discussing sexual issues with older patients or make erroneous assumptions about sexual activity in older populations which can result in sexual health concerns not being identified or acknowledged [17]. It is important to note that intersectionality is common and that many patients may identify with multiple marginalized populations, increasing the extent to which they may experience inequities of sexual healthcare treatment.

Accessibility: It is known that people in rural areas face more difficulties accessing health care than their urban counterparts, and when they do access health care they can experience poorer outcomes [29]. In general, rural residents have direct access to a much smaller number and scope of health services and providers than urban residents, despite the population being predominantly older and, as a consequence, rural residents have more health concerns and unmet needs [30, 31]. (Canadian Institute of Health Information, 2013). Urban areas often consist of hospitals that receive more funding, which can improve access to specialized services, such as sexual healthcare [19]. Thus, geographical inequities can create barriers for patients who have needs that may not be met in a timely manner or by their local hospital.

In summary, the severity of impact of sexual dysfunction combined with the complexity of barriers to care within an already financially strained healthcare system underpins the lack of sexual health clinics in cancer centers worldwide. Consequently, there remains an exigent need for effective, efficient, and inclusive sexual health programming in oncology.

This paper describes the newly developed Princess Margaret Cancer Center (Toronto, Canada) Sexual Health Clinic that utilizes an innovative, hybrid model of integrated in-person and virtual care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Previous Work

In 2009, our team developed the Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation Clinic (PCRC) which was made available to all men who consented to a radical prostatectomy at the Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto, Canada. The PCRC was a structured, manual-enhanced, sexual rehabilitation clinic for prostate cancer survivors and their partners. In 2012, PCRC was introduced into usual care with a patient “opt-out” option. A PCRC program evaluation revealed significant patient interest and uptake [32]. In a comparison to patient experience before the implementation of PCRC, PCRC patients reported improved biomedical and psychosocial outcomes, and exceptional satisfaction scores in care provision [8]. In 2019, the True North SHAReClinic was introduced as an alternative option to PCRC. The TrueNorth SHAReClinic is a facilitated virtual clinic containing over 200 pages of expert-informed content and 22 videos (physician, patient, and partner) and several specialized, virtual, self-management features. Evaluation of the TrueNorth SHAReClinic revealed 71% patient engagement at 1-year follow- up, substantial patient activity on the platform, and non-inferior sexual health outcomes compared to “best practice” and the scientific literature [33]. Combined, PCRC and the TrueNorth SHAReClinic have provided treatment to over 2500 patients. Currently, TrueNorth SHAReClinic is embedded as usual care in 5 leading Canadian cancer centers.

Overall, the results from PCRC and the TrueNorth SHAReClinic emphasize the importance of sexual healthcare and support the expansion of innovative models of sexual healthcare to other oncology populations. Accordingly, the Princess Margaret Sexual Health Clinic (SHC) evolved from a fusion of the Prostate Cancer (Sexual) Rehabilitation Clinic at Princess Margaret (in-person) and the Movember TrueNorth Sexual Health And Rehabilitation e-Clinic (virtual) for prostate cancer patients. The resultant hybrid care model was adapted to include six additional cancer sites (Cervical, Ovarian, Testicular, Bladder, Kidney, and Head and Neck) with plans to expand to all cancer sites. The SHC is theoretically founded in a biopsychosocial framework and emphasizes interdisciplinary intervention teams, active participation by the partner, and a broad-spectrum medical, psychological, and interpersonal approach. Clinical and Patient Reported Outcome (PRO) measures are serially collected via the SHC virtual portal to assess quality assurance and effectiveness. The launch of the SHC utilized a Hybrid Type 3 implementation methodology to ensure seamless integration into the patient workflows across the cancer sites of a high-volume cancer center.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The Sexual Health Clinic (SHC)

Goal: The goal of the SHC is to assist patients and their partners achieve optimal sexual function, satisfaction, and interpersonal intimacy post-cancer treatment. A core value of SHC is to provide equitable, inclusive care in an environment that fosters openness and sensitivity to racial, cultural, sexual, and gender diverse populations.

Patient Population: The SHC provides care to patients (and

partners) with prostate, testicular, cervical, ovarian, bladder, kidney, and head and neck cancers. These cancer sites were chosen for their diversity in age, biological sex, type of sexual dysfunction, and pelvic and non-pelvic concerns. Successful treatment across these diverse presentations will allow for easy expansion to all cancers in the future.

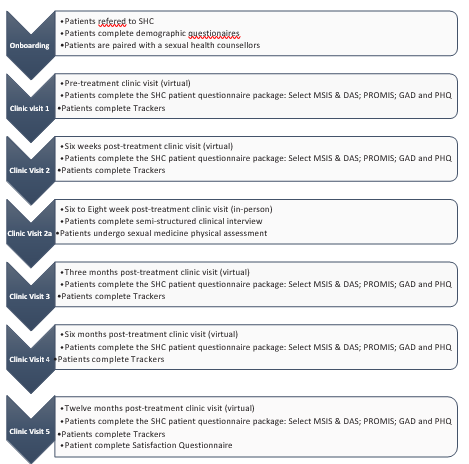

Clinic Visit Schedule: The SHC visit schedule includes a virtual clinic visit at pre-treatment (T1), and 6 weeks (T2), 3 months (T3), 6 months (T4), and 12 months (T5) post-cancer treatment. The virtual visits are facilitated by highly trained sexual health counselors (SC) who provide education, support, and guidance via the SHC platform-based asynchronous and synchronous chat, telephone, and or videoconference. At 6-10 weeks post-cancer treatment (T2a), patients/couples also attend an in-person clinic where they are seen by an interdisciplinary team for sexual medicine assessment and prescription (note: additional in- person follow-up visits are provided as needed). The visit type and schedule are designed to maximize upfront patient education (T1), normalize treatment impact (T2), allow for early medical examination and prescription of sexual medicine (T2a), and provide long-term sexual rehabilitation (T3, T4, T5) (Figure 1)

Figure 1 SHC Visit Schedule.

Assessment: The SHC patient sexual health assessment is a three-step process comprising of a semi-structured clinical interview, completion of a standardized questionnaire package, and a physical exam. The semi-structured interview is performed by SCs during the patient’s first in-person visit (T2a). The comprehensive clinical interview documents the patient’s: 1) medical and psychiatric history, cancer type and treatment, gender, and sexual orientation; 2) previous and current use of sexual medicine or devices; 3) patient concerns regarding sexual desire, arousal, plateau, orgasm, body image, pain, satisfaction; and 4) concerns regarding relationship satisfaction and intimacy. The SHC patient questionnaire package includes the Miller Social Intimacy Scale (MSIS)-only 4 items, the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)-only 1 item, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)-Full Profile Sexual Function and Satisfaction, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and satisfaction with SHC questionnaire. Additionally, patients are prompted to regularly complete sexual functioning trackers (Likert scale 1-low to 10-high) including sexual desire/interest, erection firmness (Male), lubrication (Female), sexual activity in the last month, sexual satisfaction, intimacy (couple), and body image concerns. The questionnaires are completed by patients at the end of each virtual care visit, while the trackers are completed per patient preference, with a minimum of once per virtual care visit. Finally, during the first in-person visit, if applicable, the patient will undergo a sexual medicine physical assessment. Combined, the SHC assessment is used to guide the development of a personalized biopsychosocial treatment plan.

Intervention: The SHC intervention is theoretically founded in a biopsychosocial framework combined with an interdisciplinary provision of care. The intervention consists of three major components: virtual access to education modules; virtual care facilitation by a sexual health counselor; and in-person clinic visits with an interdisciplinary sexual health team.

Education Modules: Patient/couple experience is tailored

through the assignment of specific education modules based on the patient’s cancer type, treatment type, biological sex, and relationship status (single or coupled). A total of eighty-one multi- modal education modules, inclusive of figures, photos, videos, and animations, were created specific to the physical, psychological, and interpersonal impacts of cancer and its treatment on sexual health (Table 1:

Table 1: SHC Education Modules.

|

ALL PATIENTS |

URINARY AND BOWEL |

|

Introduction

Resuming Sexual Activity

|

|

|

Male Sexual Function - Physical |

Female Sexual Function - Physical |

|

|

|

Male Sexual Function - Psychological |

Female Sexual Function - Psychological |

|

|

|

Sexual Wellbeing And Age |

Head & Neck |

|

|

|

Fertility |

Social Support |

|

|

|

FATIGUE |

|

|

|

|

All Patients |

|

|

|

|

Impact On Partner |

Impact On Couple |

|

|

|

Patient Preference Module Unique Needs Of LGBTQ2+ Unique Needs Of Marginalized Minorities Cultural Factors And Sexual Health Mindfulness And Sexual Wellbeing Exercise And Sexual Health Sexual Health And Loss More on Pelvic Health Physiotherapy Pre-mature Menopause |

|

Education Module Menu). Additionally, patients can further customize their experience by adding “patient preference” modules to their virtual experience (e.g. Unique Needs of LGBTQ2+). All education modules are founded based on internationally recognized guidelines, empirical research, and expert opinion. Combined with the educational modules the virtual platform offers access to symptom trackers and goal- setting strategies to empower participant self-management. Finally, the online clinic also features a professionally curated, digital, health library including electronic books, relevant leading articles, and videos on sexual health and rehabilitation.

Accounting for the seven cancers, the biological sex of the patient, and the cancer treatment options, a total of 32 unique patient streams were determined (e.g. a male bladder cancer surgery patient stream, a female bladder cancer surgery patient stream, a male bladder cancer surgery plus chemotherapy patient stream, etc.). Using the Education Module Menu, education

modules were embedded into each of the 32 unique patient streams based on known relevance to a patient’s experience in that particular stream. For example, see Table 2

Table 2: Example of Unique Patient Streams.

|

BLADDER CANCER |

TESTICULAR CANCER |

|

Pre-Tx |

Pre-Tx |

|

Sexual Health and Wellbeing as an Important Part of Cancer Care |

Sexual Health and Wellbeing as an Important Part of Cancer Care |

|

About the SHC |

About the SHC |

|

Understanding the Sexual Response Cycle |

Understanding the Sexual Response Cycle |

|

The Sexual Response Cycle and the Impact of Bladder Cancer Treatment |

The Sexual Response Cycle and the Impact of Testicular Cancer Treatment |

|

Fertility and Sperm-banking |

Fertility and Sperm-Banking |

|

Urinary Diversions |

Scar and Testicular Prosthesis |

|

Potential Changes In Your Erectile Function |

Potential Changes In Your Erectile Function |

|

Frequently Asked Questions |

Frequently Asked Questions |

|

Managing Your Expectations of Erectile Recovery |

|

|

6 wks Post tx |

6 wks post tx |

|

Revisiting Managing Your Expectations |

|

|

Overview of Pro-Erectile Therapy |

Erectile Dysfunction and Erection Pills |

|

Pro-erectile Treatment Decision-making |

|

|

Resuming Sexual Activity |

Resuming Sexual Activity |

|

Exploring And Expanding Your Sexual Repertoire |

Exploring And Expanding Your Sexual Repertoire |

|

Body Image – Adapting To Your Ostomy |

Body Image – Adapting To The Removal Of A Testicle |

|

|

More on Fertility |

|

3 mos post tx |

3 mos post tx |

|

Potential Changes In Your Desire |

Potential Changes In Your Desire |

|

Potential Changes In Your Orgasm |

Potential Changes In Your Orgasm |

|

Male Sexual Performance Anxiety |

Male Sexual Performance Anxiety |

|

Impact on Your Masculinity |

Impact On Your Masculinity |

|

Impact On Your Sexual Partner (Female) |

Impact On Your Sexual Partner (Female) |

|

If You Are Single…The Issue of Disclosure |

If You Are Single…The Issue of Disclosure |

|

Maintain Intimacy – understanding intimacy and passion |

Maintain Intimacy – understanding intimacy and passion |

|

Sensate Focus |

Sensate Focus |

|

6 months post tx |

6 months post tx |

|

Re-visiting Your Pro-Erectile Therapy |

Re-challenging pro-erectile pills |

|

Age and Sexual Health (Female Partner) |

Age, Sexual Health, and Sexual Identity |

|

Age and Sexual Health (Patient) |

Grief as a Normal Emotional Response |

|

Grief as a Normal Emotional Response |

What is Good Sex? |

|

What is Good Sex? |

Why do I Engage In Sex? |

|

Why do I Engage In Sex? |

Common Interpersonal Misunderstandings |

|

Common Interpersonal Misunderstandings |

The Big Picture: Adapting to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer |

|

|

Adaptation to Changes in Your Sex Life |

|

|

Understanding Your Social Support |

|

|

Continued Communication with Your Sexual Health Coach |

|

|

SHC is Not Going Anywhere |

|

|

|

|

12 months post tx |

|

|

“Re-challenging” with pro-erectile therapy |

|

|

The Big Picture: Adapting to the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer |

|

|

Adaption to changes in your sex life |

|

|

Understand Your Social Support |

|

|

Continued Communication with Your Sexual Health Coach |

|

|

SHC is Not Going Anywhere |

|

comparing the stream of a male bladder cancer surgery patient and a testicular cancer surgery patient.

Virtual Sexual Health Counselors: In an effort to “humanize the technology” and promote patient engagement [33], the SHC virtual care platform is facilitated by sexual health counselors via chat, telephone, or videoconference. The SHC counselors provide an additional layer of personalization through the provision of psychosexual education/guidance, supportive counseling, and motivational strategies to foster self-management and SHC treatment adherence. Training for our SHC counselors involves successful completion of the Sexual Health in Cancer Part 1 and Sex Counselling in Cancer Part II courses offered through the de Sousa Institute (https://www.desouzainstitute.com). The SHC counselors must also complete specialized training in virtual- based communication and documentation, and platform-based features designed to enhance participant-counselor interaction (e.g. participant engagement and tracker monitoring). Additionally, the SHC counselors receive applied clinical training through SHC Case Rounds and direct supervisor-counselor shadowing during in-person clinic patient encounters.

In-person Clinic Visits: Patients/couples attend an in-person clinic where they are seen by an interdisciplinary team inclusive of urologists, psychologists, nurses, and SCs. During their clinic visit, patients undergo both a physical examination for presenting sexual dysfunction, and a psychosexual assessment for related psychosocial concerns. Where appropriate, clinic visits can also be used for in-person training in sexual medicine prescription such as intracavernosal injection training or vaginal dilator therapy. As well, the SC can schedule additional in-person follow- ups for patients requiring changes to their sexual medicine regimen, medical examination, and sexual medicine prescription.

Quality Assurance and Research Program: Embedded in the SHC is a quality assurance, improvement, and research program. At the core of this program is the SHC database (SHC-DB), an active database in which PRO data is serially collected, scored, and uploaded directly from the SHC platform. The SHC-DB includes data fields specific to patient demographics, patient engagement (e.g. rates of enrolment, attrition, completion), and clinic evaluation (sexual health questionnaires/trackers). The research program is designed to measure patient engagement, evaluate the effectiveness of SHC, and provide a ‘real-world laboratory’ for conducting biomedical and psychosocial research in sexual medicine.

SHC Implementation

Implementation of SHC is guided by the Quality Implementation Framework and includes 1) identification of unique implementation factors within host sites, 2) creation of a systematic structure for implementation, 3) allowance for ongoing structure evolution, and 4) development of improvement strategies for future applications. In this regard, our team identified “site champions” for each of the seven cancer sites. The site champions participated in three brainstorming sessions designed to tailor integration of the SHC into patient workflow and clinic protocol. Additional key site group/clinic personnel were also interviewed to further explicate approaches to SHC integration into patient and practitioner experience. In total, 20 interviews were performed and a pragmatic qualitative analysis of the interview transcripts is currently proceeding. To further enhance the interview data, a clinic-embedded research assistant is also documenting clinic-based enablers and barriers to successful implementation. The SHC will employ known patient- based engagement approaches for online healthcare services including: establishing product legitimacy and security; usability testing and enhanced functionality; participant and SC platform training; SC facilitation; information tailoring and guided usage; patient and HCP feedback; and automated reminder features. Combined, this data collection process is helping to inform the evolution of successful SHC integration strategies that serve to close gaps in sexual healthcare across cancer sites and within patient experience.

CONCLUSION

The SHC is an innovative care model which has the potential to close the gap in sexual healthcare during a time of limited healthcare funds/resources. The SHC is designed as a transferable, stand-alone clinic which can be efficiently shared with cancer centers and other institutions providing care to cancer patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND FUNDING

The Sexual Health Clinic is funded exclusively by The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Barbera L, Zwaal C, Elterman D, McPherson K, Wolfman W, Katz A, et al. Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People with Cancer. J Curr Oncol. 2017; 24: 192-200.

- Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: Challenges and intervention. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012; 30: 3712-3719

- Katz A, Agrawal LS, Sirohi B. Sexuality After Cancer as an Unmet Need: Addressing Disparities, Achieving Equality. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022; 42: 1-7.

- Bessa A, Martin R, Häggström C, Enting D, Amery S, Khan MS, et al. Unmet needs in sexual health in bladder cancer patients: A systematic review of the evidence. BMC Urology. 2020; 20: 64.

- Pup DL. Management of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in estrogen

-

sensitive cancer patients. Gynecol Endocrinol .2012; 28: 740–745.

- Stavraka C, Ford A, Ghaem-Maghami S, Crook T, Agarwal R, Gabra H, et al. A study of symptoms described by ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012; 125: 59–64.

- Goossens-Laan CA, Kil PJM, Ruud Bosch JLH, Vries JD. Pre-diagnosis quality of life (QoL) in patients with hematuria: comparison of bladder cancer with other causes. Qual Life Res. 2013; 22: 309–315.

- Matthew A, Lutzky-Cohen N, Jamnicky L, Currie K, Gentile A, Mina DS, et al. The prostate cancer rehabilitation clinic: a biopsychosocial clinic for sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Curr Oncol. 2018; 25: 393-402.

- White ID, Wilson J, Aslet P, Baxter AB, Birtle A, Challacombe B.Development of Uk guidance on the management of erectile dysfunction resulting from radical radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Clin Pract. 2015; 69: 106–123.

- Low C, Fullarton M, Parkinson E, O’Brien K, Jackson SR, Lowe D, et al. Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol. 2009; 45: 898–903.

- Schover LR., van der Kaaij M, Dorst EV, Creutzberg C, Huyghe E, Kiserud CE. Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. EJC Suppl. 2014; 12: 41-53.

- Katz A, Dizon DS. Sexuality after cancer: a model for male survivors. JSex Med . 2016; 13: 70-78.

- Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after Treatment for Early Prostate Cancer Exploring the Meanings of``of``Erectile Dysfunction’’. J Gen Intern Med. 2001; 16: 649-55.

- Goldfarb S, Mulhall J, Nelson C, Kelvin J, Dickler M, Carter J. Sexual and reproductive health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol . 2013; 40: 726–744.

- Wittmann, D. Emotional and sexual health in cancer: Partner and relationship issues. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care . 2016; 10: 75–80.

- Vermeer WM, Bakker RM, Kenter GG, Stiggelbout AM, Ter Kuile MM. Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Support Care Cancer . 2016; 24: 1679-1687.

- Krouwel EM, Albers LF, Nicolai MPJ, Putter H, Osanto S, Pelger RCM, et al. Discussing Sexual Health in the Medical Oncologist’s Practice: Exploring Current Practice and Challenges. J Cancer Educ. 2020; 35: 1072–1088.

- Hall KS. Cultural differences in the treatment of sex problems. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2019; 11: 29-34.

- Romanow R. Building on Values: Report of the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. 2002.

- Flynn KE, Reese JB, Jeffery DD, Abernethy AP, Lin L, Shelby RA, et al. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psychooncology. 2012; 21: 594–601.

- Althof SE, Rosen RC, Perelman MA, Rubio-Aurioles E. Standard operating procedures for taking a sexual history. J Sex Med, 2013;10: 26-35.

- Parish SJ, Clayton AH. Continuing medical education: Sexual medicine education: Review and commentary (CME). Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007; 4: 259-268.

- Parish SJ, Rubio-Aurioles E. Education in sexual medicine: proceedings from the international consultation in sexual medicine, 2009. J SexMed. 2010; 7: 3305-3314.

- Christiansen RS, Azawi N, Højgaard A, Lund L. Informing patients about the negative effect of nephrectomy on sexual function. Turk J Urol. 2020; 46: 18–25.

- Jabson JM, Kamen CS. Sexual minority cancer survivors’ satisfactionwith care. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2016; 34: 28-38.

- Lee TK, Handy AB, Kwan W, Oliffe JL, Brotto LA, Wassersug RJ. Impact of prostate cancer treatment on the sexual quality of life for men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2015; 12: 2378-2386.

- Boehmer U. LGBT populations’ barriers to cancer care. Semin OncolNurs. 2018; 34: 21-29.

- Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, Vadaparampil ST, Nguyen GT, Green BL. et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015; 65: 384-400.

- Bosco C, Oandasan I. Review of family medicine within rural and remote Canada: Education. Practice, and Policy. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada. 2016.

- Parsons K, Gaudine A, Swab M. Experiences of older adults accessing specialized health care services in rural and remote areas: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2021;19: 1328-1343.

- Sibley LM, Weiner JP. An evaluation of access to health care services along the rural-urban continuum in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011; 11.

- Matthe WA, Jamnicky L, Currie K, Gentile A, Trachtenberg J, Alibhai, et al. 320 Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation: Outcomes of a Sexual Health Clinic. The Journal of Sexual Medicine.2018; 15: S84.

- Matthew AG, Trachtenberg LJ, Yang ZG, Robinson J, Petrella A, McLeod D, et al. An online Sexual Health and Rehabilitation eClinic (TrueNTH SHAReClinic) for prostate cancer patients: a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2022; 30: 1253-1260.

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory in collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics: A 2022 special report on cancer prevalence. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2022. Available at: cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2022-EN (accessed: Dec 5, 2022).

- Ball M, Nelson CJ, Shuk E, Starr TD, Temple L, Jandorf L, et al. (2013). with Sexual Dysfunction Post-rectal Cancer Treatment: A Qualitative Study. J Cancer Educ. 2013; 28: 494-505.

- Metusela C, Ussher J, Perz J, Hawkwy A, Morrow M, Narchal, et al. “In My Culture, We Don’t Know Anything About That”: Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women. Int.J. Behav. Med. 2017; 24: 836–845.