IFN-γ, MCP-1 and RANTES as Potential Predictive Biomarkers of Treatment Response to Biologic Agents in Psoriatic Arthritis

- 1. Department of Dermatology, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan

- 2. Department of Medical Research, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan

- 3. Institute of Biomedical Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, Taiwan

- 4. Department of Internal Medicine, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan

- 5. National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

- 6. Integrated Care Center of Psoriatic Disease, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan

Abstract

Background: Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that substantially impact patients’ quality of life. Despite advances in biologic treatments, up to 40% of patients exhibit partial or poor responses. There remains an urgent and unmet need for predictive tools to personalize biologic selection and improve disease management.

Objectives: To identify predictive biomarkers of treatment response to biologic agents in patients with PsA.

Methods: A total of 19 patients with PsA who were treated with at least one biologic agent were included in this study. Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) were collected, stimulated with Streptococcus pyogenes, then treated with various biologic agents in vitro. Cytokine levels were quantified through a multiplex immunoassay before and after biologic treatment. Clinical disease activity was evaluated in terms of tender joint count, swollen joint count, and Disease Activity In Psa (DAPSA) scores before and after biologic treatment. Spearman’s rho was used to analyze the correlations between cytokine level and clinical improvement.

Results: Levels of IFN-γ, MCP-1 and RANTES (CCL5) after biologic treatment were significantly associated with an improvement in DAPSA scores (p = 0.012, p = 0.047, and p = 0.003, respectively). However, no significant associations were observed for the other cytokines.

Conclusion: IFN-γ, MCP-1 and RANTES may serve as reliable predictive biomarkers of clinical response to biologic agents in patients with PsA. Establishing a predictive model combining PBMC testing with cytokine profiling may represent a novel personalized approach for selecting optimal biologic treatments.

Keywords

• IFN-γ

• MCP-1

• RANTES

• Streptococcus Pyogenes

• Treatment Response

• Biologic Agents

• Psoriatic Arthritis

Citation

Hsueh CM, Yu SJ, Lai KL, Wu YD, Yen CY (2025) IFN-γ, MCP-1 and RANTES as Potential Predictive Biomarkers of Treatment Response to Biologic Agents in Psoriatic Arthritis. JSM Trop Med Res 6(1): 1024.

ABBREVIATIONS

PsA: Psoriatic Arthritis; PBMC: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells; DAPSA: Disease Activity In PsA; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-α; IL-6: Interleukin-6; PDGF: Platelet-Derived Growth Factor; TJC: Tender Joint Count; SJC: Swollen Joint Count; CFU: Colony Forming Units; IFN-γ: Interferon-γ; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; MIP-1α: Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1α; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; IP-10: IFN-γ Induced Protein-10; APC: Antigen-Presenting Cells; MMP: Matrix Metalloproteinase;

INTRODUCTION

Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) is a complex multifactorial disease characterized by diverse manifestations of joint involvement, including peripheral and axial arthritis, enthesitis, bursitis, and dactylitis [1-3]. Patients with PsA often experience pain, joint swelling, and disability, which substantially affect their quality of life [4,5]. Histopathological examination of synovial tissue with PsA usually reveals tortuous vessel hyperproliferation, vascular channel dilatation, and extensive inflammatory cell infiltration [6]. These processes involve the activation of macrophages, which differentiate into osteoclasts and lead to progressive cartilage and bone erosion [7]. Key cytokines such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-17, and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) play a key role in the immune pathology of PsA [8]. Current therapeutic options include TNF-α and IL-17 inhibitors as first-line biologic agents, with anti-IL-12 and anti-IL-23 agents serving as second-line biologic agents [9]. However, responses to biologics vary considerably, with at least 40% of PsA patients exhibiting only partial or poor responses [10,11]. Therefore, a reliable and patient-centered platform is urgently required to evaluate therapeutic efficacy before the initiation of treatment.

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs)-including lymphocytes, monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells, and basophils, serve as a versatile model for investigating immune mechanisms and assessing drug responses. Because PBMCs retain the immunological profile of the individual from whom they are derived, they provide a valuable basis for evaluating the potential efficacy of biologic therapies before initiation. Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes) has long been recognized as a microbial trigger capable of precipitating psoriasis flares [12,13], and evidence indicates that it activates innate immune pathways in both guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis [14]. Previous studies done by our team also demonstrated that PBMC stimulation with S. pyogenes in vitro can induce chemokine production and mimic psoriasis/PsA flares [15,16], which can be utilized in predicting treatment response and exploring chemokine pathways.

In this study, we examined the response of PBMCs to in vitro induction with S. pyogenes and treatment with various biologic agents. By analyzing various cytokine and chemokine profiles, alongside clinical joint response data, we identified sensitive and reliable biomarkers that can be used to predict therapeutic responses in patients with PsA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Patients with PsA, aged 20–70 years, who were treated with at least one biologic agent were enrolled in this study. Patients with active infection or potential malignancies were excluded. A total of 19 patients with PsA were recruited between 2018 and 2025 from the outpatient clinics of the Department of Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology and the Department of Dermatology at Taichung Veterans General Hospital. All patients had a confirmed diagnosis of PsA by a rheumatologist.

For each patient, Tender Joint Count (TJC), Swollen Joint Count (SJC), and Disease Activity In Psa (DAPSA) scores were recorded both at baseline (day 0) and after biologic treatment. For patients with previous exposure to biologic agents (≥180 days), DAPSA scores were recorded closest to the time of PBMC testing; for patients without previous exposure or with limited exposure to biologic agents (≤180 days), DAPSA scores were recorded on day 180. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (TCVGH CE16265B, TCVGH-CE20043B).

Materials

Group A S. pyogenes were identified and prepared by the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Taichung Veterans General Hospital. After the bacteria were heat-inactivated, they were cultured on blood agar plates for 1 week before use.

Cell Culture

16 mL of blood was collected from each patient into a sodium citrate tube (Vacutainer CPT; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). PBMCs were then isolated by centrifugation at 1800 ×g for 20 min at room temperature to separate plasma, PBMCs, gel plugs, and red blood cells. After the PBMCs were washed with phosphate buffered saline, they were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere in the presence of 5% CO2 .

Cell Viability Test

PBMCs were exposed to 5 × 106, 1 × 107, and 2 × 107 colony forming units (CFUs) of S. pyogenes for 24 h. A cell viability assay was then performed by adding 0.5 mg/ mL 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide to each culture. After the reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 hour, the mixtures were centrifuged, and the supernatants were discarded. Next, 200 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to lyse the cells and dissolve the resulting purple formazan crystals. Finally, absorbance was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader at a wavelength of 570 nm.

Multiplex Assay for Cytokine Levels

PBMCs (6 × 105 cells/mL) were cultured on 12-well plates and treated for 24 h with S. pyogenes either alone or in combination with one of the following biologic agents: adalimumab (4 μg/mL), certolizumab (20 μg/ mL), golimumab (0.5 μg/mL), ustekinumab (0.25 μg/ mL), ixekizumab (3.5 μg/mL), secukinumab (16.7 or 34 μg/mL), guselkumab (1.2 μg/mL), or etanercept (2 μg/ mL). The supernatants were then collected to measure the levels of cytokines. Next, biologic concentrations were recorded at the trough level on the basis of steady state pharmacokinetics, as reported in the literature. The two concentrations of secukinumab (i.e., 16.7 and 34 μg/mL) represented typical clinical doses of 150 and 300 mg per month, respectively. A protein multiplex immunoassay system (Bio-Plex Cytokine Array System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), was used to measure the levels of various cytokines. These cytokines included IL-4, IL-6, IL-13, IL-17A, Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), TNF-α, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1), Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1α (MIP-1α), MIP-1β, PDGF-BB, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), IFN-γ-Induced Protein-10 (IP-10), and Chemokine Ligand 5 (RANTES).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Correlations between cytokine levels and clinical scores of disease activity (TJC, SJC, and DAPSA scores) were evaluated using Spearman’s rho. The results are expressed as rs and p values, with a two-sided p value of ≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Cell Viability Test

PBMCs from five patients were incubated for 24 h with S. pyogenes at concentrations of 5 × 106, 1 × 107, and 2 × 107 CFUs/mL. At all concentrations, cell viability was comparable to that of the untreated control. To obtain similar viability levels and appropriate stimulation results, 2 × 107 CFUs/mL was selected as the optimal concentration of group A S. pyogenes for subsequent experiments. Details regarding the cell viability tests are available in our previous study [16].

Association Between Clinical Scores and Laboratory Profiles

A total of 19 patients met our inclusion criteria. All these patients were treated with at least one biologic agent, of whom 14 (73.7%) were treated with two or more biologic agents.

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Psoriatic Arthritis Patients (n=19).

|

Pt |

Age/ Gender |

PSO duration |

PSA duration |

TJC |

SJC |

DAPSA score |

Time of PBMCs Test |

Course and order sequence of biologics |

Other systemic disease |

|

A |

58 y/F |

14 years |

9 years |

2 14 6 |

2 0 7 |

5.271 23.298 21.111 |

29th month of golimumab |

30 months of golimumab 20 months of adalimumab* 42 months of ixekizumab* |

- |

|

B |

69 y/F |

21 years |

21 years |

8 8 5 |

8 8 4 |

26.596 26.475 19.199 |

15th month of secukinumab |

64 months of adalimumab 20 months of ustekinumab 24 months of secukinumab |

Osteoporosis CKD Uveitis |

|

C |

47 y/M |

28 years |

17 years |

11 7 0 2 0 0 |

5 6 1 1 0 0 |

33.356 30.102 12.209 10.367 0.222 0.314 |

20th month of secukinumab |

9 months of adalimumab 54 months of ustekinumab 24 months of secukinumab 44 months of ixekizumab* 6 months of brodalumab* 4 months of guselkumab* |

CKD Hyperuricemia GERD DM HTN |

|

D |

62 y/F |

40 years |

12 years |

10 11 6 |

6 0 6 |

25.039 23.046 26.144 |

1st month of secukinumab |

48 months of adalimumab 12 months of secukinumab 54 months of ixekizumab* |

Osteoporosis SLE |

|

E |

75 y/M |

35 years |

35 years |

6 |

3 |

21.12 |

After completing treatment course of etanercept |

24 months of etanercept |

TAILS CAD Hyperuricemia DM BPH |

|

F |

57 y/M |

19 years |

11 years |

2 2 |

2 2 |

11.563 9.56 |

1st month of ixekizumab |

34 months of ustekinumab 56 months of ixekizumab |

Tuberculum sellar tumor HBV |

|

G |

55 y/M |

11 years |

10 years |

2 6 |

1 11 |

14.21 24.027 |

Between the use of adalimumab and ixekizumab |

24 months of adalimumab 30 months of ixekizumab |

DM HTN OSA |

|

H |

57 y/M |

15 years |

15 years |

2 3 4 6 |

2 3 1 4 |

16.155 24.103 13.548 26.062 |

10th month of ixekizumab |

64 months of ustekinumab 20 months of golimumab 16 months of ixekizumab 18 months of adalimumab |

- |

|

I |

62 y/F |

12 years |

6 years |

20 10 |

7 4 |

40.532 24.616 |

9th month of golimumab |

10 months of adalimumab 48 months of golimumab |

- |

|

J |

59 y/M |

13 years |

7 years |

5 |

5 |

19.771 |

46 th month of golimumab |

84 months of golimumab |

- |

|

K |

61 y/M |

28 years |

7 years |

7 7 0 |

3 3 0 |

21.6 21.648 1.750 |

12th month of adalimumab |

40 months of adalimumab 52 months of ustekinumab* 18 months of ixekinumab* |

Pulmonary hypertension |

|

L |

43 y/M |

11 years |

5 years |

7 2 |

3 2 |

19.45 14.187 |

28th month of ustekinumab |

32 months of ustekinumab 4 months of guselkumab |

- |

|

M |

55 y/M |

9 years |

6 years |

12 2 |

7 0 |

39.481 15.497 |

6th month of secukinumab |

60 months of golimumab 6 months of secukinumab |

- |

|

N |

60 y/M |

15 years |

10 years |

16 2 |

12 1 |

48.095 23.04 |

8th month of secukinumab |

60 months of golimumab 8 months of secukinumab |

HIVD DM |

|

O |

33 y/M |

15 years |

9 years |

5 |

1 |

16.180 |

44th month of guselkumab |

58 months of guselkumab |

- |

|

P |

56 y/F |

23 years |

4 years |

5 4 |

4 4 |

28.6 28.729 |

4th months of guselkumab |

4 months of guselkumab 4 months of ustekinumab* |

SLE Secondary fibromyalgia Sjogren's syndrome |

|

Q |

23 y/M |

3 years |

1.5 years |

9 25 10 |

1 6 6 |

19.042 43.04 30.05 |

4th month of ixekizumab |

4 months of golimumab 4 months of certolizumab 6 months of ixekizumab |

NAFLD |

|

R |

42 y/F |

8 years |

8 years |

8 |

8 |

36.012 |

Between the use of adalimumab and secukinumab |

96 months of adalimumab 6 months of secukinumab* |

TAILS Allergic rhinitis Hypercholesterolemia |

|

S |

62 y/M |

22 years |

9 years |

12 |

0 |

19.12 |

Between the use of ustekinumab and ixekizumab |

48 months of ustekinumab 4 months of ixekinumab* |

- |

Table 1 lists the patients’ demographic characteristics, PsA duration, baseline clinical scores of disease activity (TJC, SJC, and DAPSA scores), PBMC test timing, biologic treatment order, and other clinical characteristics. Patients D, M, N, and R received 150 mg of secukinumab per month, whereas patients B and C received 300 mg of secukinumab per month. In these two patient groups, PBMCs were treated with secukinumab at concentrations of 16.7 and 34 μg/mL, respectively.

Abbreviation: Pt: patient; PSO: Psoriasis; PSA: Psoriatic Arthritis; TJC: Tender Joint Count; SJC: Swollen Joint Count; DAPSA: Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis; PBMC: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells; CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease; GERD: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; DM: Diabetes Mellitus; HTN: Hypertension; SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; TAILS: Tnfα Inhibitor Induced Lupus-Like Syndrome; CAD: Coronary Artery Disease; BPH: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; HIVD: Herniated Intervertebral Disc; NAFLD: Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

* Patients received PBMCs test before biologics were labeled with *.

TJC, SJC, and DAPSA score were all recorded before each biologic’s treatment course.

Table 2: Laboratory profiles of patients with administered biologics (n=19).

|

Pt |

Before biologics |

After biologics |

Before induction |

After induction |

Induction |

After biologics |

Induction |

After biologics |

Biologics |

|

DAPSA |

MCP-1 |

IFN-γ |

RANTES |

||||||

|

A |

5.271 |

7.212 |

1862.21 |

1925.28 |

107.72 |

107.68 |

1806.47 |

1490.32 |

gol |

|

23.298 |

20.251 |

1874.86 |

105.21 |

1510.73 |

ada |

||||

|

B |

26.475 |

19.199 |

1765.35 |

1866.09 |

85.68 |

89.51 |

850.16 |

568.75 |

ust |

|

26.596 |

7.294 |

1870.76 |

102.91 |

720 |

ada |

||||

|

19.199 |

8.165 |

1828.06 |

66.92 |

619.31 |

sec |

||||

|

C |

10.367 |

1.653 |

1859.3 |

1838.34 |

100.13 |

76.76 |

1473.91 |

1024.4 |

ixe |

|

30.102 |

12.301 |

1839.49 |

102.31 |

885.03 |

ust |

||||

|

33.356 |

28.621 |

1829 |

105.29 |

1429.38 |

ada |

||||

|

12.209 |

10.367 |

1850.23 |

84.74 |

1083.71 |

sec |

||||

|

D |

25.039 |

17.039 |

1637.36 |

1926.28 |

244.94 |

269.64 |

2716.11 |

3231.78 |

ada |

|

23.046 |

20.046 |

1785.35 |

269.05 |

2994.89 |

sec |

||||

|

E |

21.12 |

14.1 |

1631.91 |

1812.78 |

236.09 |

241.47 |

6092.31 |

4697.63 |

eta |

|

F |

9.56 |

5.13 |

3829.46 |

4096.26 |

367.78 |

383.17 |

4537.27 |

4125.88 |

ixe |

|

11.563 |

5.132 |

4086.31 |

365.71 |

4639.91 |

ust |

||||

|

G |

14.21 |

9.13 |

2683.3 |

3360.41 |

84.7 |

69.96 |

2938.48 |

3022.08 |

ada |

|

16.23 |

4.01 |

3427.81 |

80.04 |

3114.53 |

ust |

||||

|

24.027 |

10.027 |

3569.89 |

78.86 |

2726.87 |

ixe |

||||

|

H |

16.155 |

24.103 |

1354.84 |

2032.6 |

66.37 |

61.96 |

3237.65 |

2632.06 |

ust |

|

24.103 |

13.548 |

1354.84 |

66.72 |

2623.54 |

gol |

||||

|

13.548 |

26.062 |

1463.88 |

63.72 |

2249.24 |

ixe |

||||

|

26.062 |

8.032 |

1640.13 |

57.42 |

1093.1 |

ada |

||||

|

I |

24.616 |

3.694 |

1333.22 |

777.67 |

54.73 |

49.66 |

536.54 |

247.34 |

gol |

|

40.532 |

24.616 |

1296.09 |

51.54 |

549.19 |

ada |

||||

|

J |

19.771 |

0.097 |

2657.21 |

2228.19 |

111.16 |

55.51 |

188.05 |

203.09 |

gol |

|

K |

21.6 |

5.201 |

1831.93 |

1961.64 |

200.39 |

222.11 |

3419.22 |

2693.66 |

ada |

|

21.648 |

4.735 |

1971.16 |

201.66 |

3307.75 |

ust |

||||

|

L |

19.45 |

3.187 |

14077.5 |

14123.5 |

23.63 |

26.27 |

4849 |

3531 |

ust |

|

14.187 |

0.135 |

8993 |

9.2 |

2109 |

gus |

||||

|

M |

39.481 |

21.471 |

715.65 |

341.88 |

61.32 |

64.51 |

280.56 |

823.34 |

gol |

|

15.497 |

8.050 |

745.35 |

46.81 |

386.13 |

sec |

||||

|

N |

48.095 |

18.040 |

322.53 |

238.61 |

34.58 |

45.04 |

806.51 |

704.8 |

gol |

|

23.04 |

14.040 |

361.52 |

35 |

627.33 |

sec |

||||

|

O |

16.302 |

4.302 |

9724.5 |

7067 |

32.1 |

24.19 |

1646 |

1680 |

gus |

|

P |

28.6 |

22.34 |

913.18 |

823.1 |

31.47 |

38.48 |

334.99 |

431.76 |

gus |

|

28.729 |

3.154 |

297.05 |

18.23 |

117.86 |

ust |

||||

|

Q |

19.042 |

18.164 |

1907.96 |

1171.93 |

113.14 |

73.99 |

1539.88 |

1190.59 |

gol |

|

43.04 |

26.04 |

1336.28 |

82.99 |

1344.37 |

cer |

||||

|

30.05 |

21.056 |

1899.43 |

97.07 |

1431.91 |

ixe |

||||

|

R |

36.012 |

0.01 |

768.63 |

377.64 |

72.94 |

38.32 |

237.35 |

264.88 |

ada |

|

S |

19.12 |

0.155 |

1144.38 |

1592.2 |

102.45 |

113.39 |

482.02 |

503.04 |

ust |

Abbreviation: Pt: Patient; DAPSA=Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis; IFN-γ: Interferon-γ; RANTES: Regulated Upon Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted, also known as CCL5; ada: Adalimumab; ust: Ustekinumab; gol: Golimumab; ixe: Ixekizumab; sec: Secukinumab; eta: Etanercept; gus: Guselkumab; cer: Certolizumab.

PBMC testing results and their clinical disease severity scores. Cytokine analyses involved IFN-γ, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, PDGF, RANTES, VEGF, IL-6, IL-17, IL-4, and IL-13. nly the results of IFN-γ, MCP-1 and RANTES are presented, which were significantly correlated with the clinical scores of disease severity.

Table 3: Clinical association between clinical TJC, SJC, DAPSA and laboratory profile (n=19).

|

Reduction Ratio |

TJC (after-before) |

SJC (after-before) |

DAPSA (after-before) |

|||

|

rs |

p value |

rs |

p value |

rs |

p value |

|

|

IFN-r (%) |

0.05 |

0.777 |

0.12 |

0.451 |

0.39 |

0.012* |

|

Hu IP-10 (%) |

0.21 |

0.184 |

0.09 |

0.598 |

0.17 |

0.308 |

|

MCP-1 (%) |

0.19 |

0.238 |

-0.02 |

0.881 |

0.32 |

0.047* |

|

MIP-1α (%) |

0.10 |

0.544 |

0.06 |

0.718 |

0.15 |

0.350 |

|

MIP-1β (%) |

0.34 |

0.080 |

0.30 |

0.118 |

0.28 |

0.147 |

|

PDGF (%) |

0.15 |

0.340 |

0.06 |

0.733 |

0.25 |

0.128 |

|

RANTES (%) |

0.22 |

0.170 |

0.14 |

0.379 |

0.46 |

0.003** |

|

VEGF (%) |

0.06 |

0.694 |

0.01 |

0.954 |

0.19 |

0.228 |

|

IL-6 (%) |

0.14 |

0.402 |

0.00 |

0.993 |

0.27 |

0.093 |

|

IL-17 (%) |

0.10 |

0.524 |

0.02 |

0.898 |

0.30 |

0.063 |

|

IL-4 (%) |

0.03 |

0.841 |

-0.02 |

0.917 |

0.28 |

0.079 |

|

IL-13 (%) |

0.07 |

0.702 |

-0.12 |

0.521 |

0.22 |

0.236 |

Abbreviation: TJC: Tender Joint Count; SJC: Swollen Joint Count; DAPSA: Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis; IFN-γ: Interferon-γ; Hu IP-10: Human Interferon Gamma Induced Protein-10; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1; MIP-1α: Macrophage Inflammatory Protein; PDGF: Platelet-Derived Growth Factor; RANTES: Regulated Upon Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted, also known as CCL5; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; IL-6: Interleukin 6.

Table 3 presents the statistical analysis results of the clinical association between the levels of cytokines and the differences in disease activity clinical scores, expressed as rs and p values.

Our results indicated that the reduction differences of DAPSA scores was strongly associated with the levels of IFN-γ (p = 0.012), MCP-1 (p = 0.047) and RANTES (p = 0.003, Table 3). However, we observed no significant association between the level of other cytokines and the reduction of DAPSA scores.

DISCUSSION

PsA is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by synovitis, enthesitis, and systemic inflammation. Biologic therapies targeting inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-17A have considerably improved disease management. However, predicting individual patient responses to these therapies remains challenging. Our study indicates that the levels of IFN-γ, MCP-1, and RANTES may serve as potential predictive biomarkers of treatment response to biologic agents in patients with PsA. In the following, we discuss the physiological roles of IFN-γ, MCP-1, and RANTES and propose mechanisms linking their serum concentrations to therapeutic outcomes.

IFN-γ is a key cytokine involved in the Th1/Th17 predominant pathogenesis of psoriasis. It is primarily produced by activated Th1 cells, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, and Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs), such as macrophages and dendritic cells. Its production is stimulated by IL-12 and IL-18, which are secreted by APCs in response to pathogens or inflammatory signals. Once released, IFN-γ activates APCs, contributing to the differentiation of Th17 cells and the induction of IL 17 inflammatory cascades [17,18]. IFN-γ also functions synergistically with TNF-α, inducing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and the recruitment of additional immune cells to inflamed tissues. In addition, IFN-γ directly affects skin and bone cells. It influences the proliferation of keratinocytes and contributes to bone erosion by promoting osteoclastogenesis [19].

MCP-1 (CCL2) is a CC-chemokine involved in the recruitment and activation of monocytes [20]. It binds to the CCR2 receptor, facilitating the migration of monocytes to sites of inflammation, where they differentiate into macrophages and contribute to chronic inflammatory responses. Furthermore, MCP-1 has also been identified as a critical mediator of joint inflammation and osteoclastogenesis [21]. Elevated MCP-1 promotes the recruitment of osteoclast precursors, thus contributing to bone erosion and tissue remodeling. Clinically, elevated MCP-1 levels are not only observed in synovial tissue and fluid of PsA patients, but also in serum of PsA patients compared with non-inflammatory controls, suggesting a systemic inflammatory burden [22].

RANTES (Regulated upon Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and Secreted), also known as CCL5, is a CC motif chemokine involved in the recruitment of T cells, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and natural killer cells to sites of inflammation [23]. This chemokine plays a key role in both the initiation and amplification of immune responses in inflammatory arthritis [24,25]. RANTES is produced by activated T lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, platelets, and synovial fibroblasts and is upregulated by TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ. In PsA, RANTES is overexpressed in lesional skin and synovial fluid [26], which contributes to chronic inflammation by maintaining T-cell infiltration and cytokine loops. RANTES activates synovial fibroblasts, which in turn produce Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-1 and MMP-13) that degrade cartilage collagen [27]. Research has indicated that RANTES levels are correlated with disease activity and tissue damage and that exhibits a strong chemotactic effect on circulating osteoclast progenitor cells, indicating a direct role in bone erosion [28].

In this study, we hypothesized that the levels of IFN-γ, MCP-1, and RANTES before and after biologic treatment may serve as an indicator of the immune signals driving their disease, thus predicting which biologic therapy would most effectively interrupt those signals. For instance, a marked difference in RANTES levels may indicate a disease predominantly driven by TNF-α, particularly because TNF-α strongly induces the production of RANTES from synovial cells. These patients may positively respond to TNF inhibitor therapy, which directly downregulates various downstream inflammatory chemokines, including RANTES.

In a previously published study, we discovered that IFN-γ and RANTES served as key biomarkers of paradoxical PsA, a condition characterized by new-onset or worsening PsA induced by biologic therapy [15]. In patients with paradoxical PsA, we observed that the levels of RANTES were almost two times higher than those induced by Streptococcus stimulation. Interestingly, the levels of IFN-γ were significantly decreased, likely because of a major RANTES-driven immune shift. Although the three previously encountered cases of paradoxical PsA were not included in the study, they exhibited similar IFN-γ and RANTES profiles. These findings indicated that a decrease in the levels of both IFN-γ and RANTES reflected a favorable biologic response in typical PsA, whereas an increase in the levels of RANTES with IFN-γ suppression suggested paradoxical disease driven by dysregulated immune activation, which supports our hypothesis.

Few studies have pursued similar objectives with reliable outcomes. In a review study, Makos et al. [29], identified several potential biomarkers for predicting therapeutic responses to biologic agents. However, none of these biomarkers have been adopted in clinical practice because of their limited specificity. In our previous study on psoriasis, we reported that IFN-γ, IL-13, IFN-γ/IL-4, IFN-γ/ IL-13, IL-17A/IL-4, and IL-17A/IL-13 served as predictive biomarkers of biologic responses in patients with psoriasis [16]. Given these findings, our goal is to identify predictive biomarkers for PsA and establish a reliable platform for personalized biologic therapy selection.

Currently, selecting a biologic therapy for PsA is primarily based on the patient’s clinical presentation and the physician’s experience. Treatment typically follows a trial-and-error approach, in which a biologic agent is administered and its effectiveness is evaluated over time. If the patient’s response is inadequate or if the disease continues to progress, the regimen is switched to either another biologic agent with the same target or one with a different mechanism of action, and this cycle continues until satisfactory disease control is achieved. However, this approach is inefficient for refractory patients, considering the substantial amount of time and finance required. Generally, biologic therapies are expensive and impose a considerable economic burden even with insurance coverage. Additionally, trial-and-error approaches often contribute to physical and psychological distress. Since PsA is a disease that involves multiple systems, it can severely impact a patient’s quality of life. In addition, the damage caused by PsA can be irreversible, such as scarring and joint destruction. Therefore, predicting the optimal biologic therapy at the time of diagnosis is essential to achieve early disease control, prevent irreversible damage, reduce financial burdens, and improve overall quality of life.

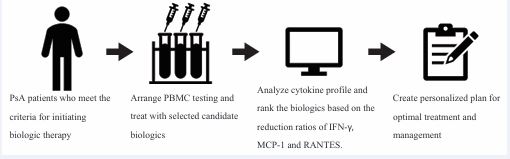

In this study, we proposed a predictive model in which blood samples are collected from patients with PsA before biologic treatment is initiated (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Proposal of predictive model including PBMC testing with cytokine profiling for selecting optimal biologic therapy for PsA patients. Abbreviation: PBMC: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells; PsA: Psoriatic Arthritis.

By stimulating PBMCs under inflammatory conditions and exposing them to different biologic agents, we can identify changes in various biomarkers, particularly IFN-γ, MCP-1, and RANTES. These biomarker profiles can help predict the biologic agent that is most likely to yield the optimal therapeutic response. This personalized approach addresses the shortcomings of our current strategy and lays the foundation for more effective and individualized treatment in the future.

Despite our promising results, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this study had a moderate sample size, which limits its statistical power to detect small differences and may lead to an overestimation of the associations observed. Second, because this was a single-center study, our patients were relatively homogeneous. PsA is a heterogeneous disease, and biomarkers may behave differently in other populations or subtypes of PsA. Third, our definition of treatment response was based on standard clinical criteria (e.g., DAPSA scores). Utilizing different outcome measures may modify the correlations with biomarkers. Lastly, no imaging techniques were used to monitor subclinical radiographic progression. Therefore, the likelihood of missing certain associations could not be excluded.

CONCLUSIONS

After biologic treatment, the levels of IFN-γ, MCP-1, and RANTES are significantly associated with improvements in DAPSA scores (p = 0.012, p = 0.047 and p = 0.003, respectively). These findings indicate that IFN-γ, MCP 1 and RANTES may serve as predictive biomarkers of therapeutic responses in PsA. This personalized approach may facilitate the selection of the optimal biologic therapy for patients with PsA.

STATEMENTS AND DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the research grant (TCVGH-1116803C, 1136803C) from the Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan. We thank the clinicians and patients who participated in this study. The authors thank the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine of Taichung Veterans General Hospital for S. pyogenes group A identification and the Biostatistics Task Force for analyses and the Center for Translational Medicine for experimental equipment of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, Republic of China. All listed authors have made a significant scientific contribution to the research in the manuscript approved its claims and agreed to be an author.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (TCVGH CE16265B, TCVGH-CE20043B). Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study. The guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed in this study protocol.

REFERENCES

- Esti L, Fattorini F, Cigolini C, Gentileschi S, Terenzi R, Carli L. Clinical aspects of psoriatic arthritis: one year in review 2024. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2025; 43: 4-13.

- Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376: 957-970.

- Gottlieb A, Merola JF. Psoriatic arthritis for dermatologists. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019; 31: 662-679.

- Gudu T, Gossec L. Quality of life in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018; 14: 405-417.

- Jiang Y, Chen Y, Yu Q, Shi Y. Biologic and Small-Molecule Therapies for Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis: Focus on Psoriasis Comorbidities. BioDrugs. 2023; 37: 35-55.

- Tenazinha C, Barros R, Fonseca JE, Vieira-Sousa E. Histopathology of Psoriatic Arthritis Synovium-A Narrative Review. Front Med. 2022; 9: 860813.

- Day MS, Nam D, Goodman S, Su EP, Figgie M. Psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012; 20: 28-37.

- Stober C. Pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2021; 35: 101694.

- Kishimoto M, Deshpande GA, Fukuoka K, Kawakami T, Ikegaya N, Kawashima S, et al. Clinical features of psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2021; 35: 101670.

- Veale DJ, Fearon U. The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2018; 391: 2273-2284.

- Sundanum S, Orr C, Veale D. Targeted Therapies in Psoriatic Arthritis- An Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24: 6384.

- Muto M, Fujikura Y, Hamamoto Y, Ichimiya M, Ohmura A, Sasazuki T, et al. Immune response to Streptococcus pyogenes and the susceptibility to psoriasis. Australas J Dermatol. 1996; 37: S54-S55.

- Groot J, Blegvad C, Nybo Andersen AM, Zachariae C, Jarløv JO, Skov L. Presence of streptococci and frequent tonsillitis among adolescents with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2020; 184: 758-759.

- Fry L, Baker BS, Powles AV, Fahlen A, Engstrand L. Is chronic plaque psoriasis triggered by microbiota in the skin? Br J Dermatol. 2013; 169: 47-52.

- Liao E, Wu Y, Lin S, Lai K, Chao W, Yen C. RANTES is a possible marker of paradoxical psoriatic arthritis. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2025.

- Hsieh CL, Yu SJ, Lai KL, Chao WT, Yen CY. IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-4, andIL-13: Potential Biomarkers for Prediction of the Effectiveness of Biologics in Psoriasis Patients. Biomed. 2024; 12: 1115.

- Carvalho AL, Hedrich CM. The Molecular Pathophysiology of Psoriatic Arthritis-The Complex Interplay Between Genetic Predisposition, Epigenetics Factors, and the Microbiome. Front Mol Biosci. 2021; 8: 662047.

- Kryczek I, Bruce AT, Gudjonsson JE, Johnston A, Aphale A, Vatan L, et al. Induction of IL-17+ T cell trafficking and development by IFN-gamma: mechanism and pathological relevance in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008; 181: 4733-4741.

- Dai H, Adamopoulos IE. Psoriatic arthritis under the influence ofIFNγ. Clin Immunol. 2020; 218: 108513.

- Lin SH, Ho JC, Li SC, Cheng YW, Hsu CY, Chou WY, et al. TNF-α Activating Osteoclasts in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis Enhances the Recruitment of Osteoclast Precursors: A Plausible Role of WNT5A-MCP-1 in Osteoclast Engagement in Psoriatic Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23: 921.

- Bursa? IU, Kehler T, Drvar V, Babarovi? E, Pej?inovi? VP, Barši? AR, et al. Predictive Value of Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 in the Development of Diastolic Dysfunction in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. Dis Markers. 2022; 2022: 4433313.

- Lembo S, Capasso R, Balato A, Cirillo T, Flora F, Zappia V, et al. MCP-1 in psoriatic patients: effect of biological therapy. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013; 25: 83-86.

- König A, Krenn V, Toksoy A, Gerhard N, Gillitzer R. Mig, GRO alpha and RANTES messenger RNA expression in lining layer, infiltrates and different leucocyte populations of synovial tissue from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and osteoarthritis. Virchows Arch. 2000; 436: 449-458.

- Sgambelluri F, Diani M, Altomare A, Frigerio E, Drago L, Granucci F, et al. A role for CCR5(+) CD4 T cells in cutaneous psoriasis and for CD103(+) CCR4(+) CD8 Teff cells in the associated systemic inflammation. J Autoimmun. 2016; 70: 80-90.

- Stanczyk J, Kowalski ML, Grzegorczyk J, Szkudlinska B, Jarzebska M, Marciniak M, et al. RANTES and chemotactic activity in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2005; 2005: 343-348.

- Macchioni P, Boiardi L, Meliconi R, Pulsatelli L, Maldini MC, Ruggeri R, et al. Serum chemokines in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with cyclosporin A. J Rheumatol. 1998; 25: 320-325.

- Agere SA, Akhtar N, Watson JM, Ahmed S. RANTES/CCL5 Induces Collagen Degradation by Activating MMP-1 and MMP-13 Expression in Human Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts. Front Immunol. 2017; 8: 1341.

- Zhang Y, Liu D, Vithran DTA, Kwabena BR, Xiao W, Li Y. CC chemokines and receptors in osteoarthritis: new insights and potential targets. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023; 25: 113.

- Makos A, Kuiper JH, Kehoe O, Amarasena R. Psoriatic arthritis: review of potential biomarkers predicting response to TNF inhibitors. Inflammopharmacology. 2022; 31: 77-87.