The Silent Struggle: How Women Experience and Conceal Postpartum Depression

- 1. Clinical Researcher, Healthcare Manager, Public Health Scholar, Clinical Optometrist, Pakistan

- 2. Health Field Officer, Public Health Scholar, Pakistan

Abstract

This qualitative study explores how women in the rural districts of Layyah and Taunsa in South Punjab, Pakistan, experience and conceal postpartum depression (PPD) within a cultural landscape shaped by spiritual beliefs, patriarchal family systems, and healthcare inaccessibility. Using a phenomenological framework, in-depth interviews were conducted with 32 women aged 20–42, all of whom had given birth within the past three years. Data were analyzed thematically, revealing five key themes: spiritualization of distress, gendered silencing, systemic healthcare barriers, reliance on traditional coping, and economic burden. Women interpreted emotional suffering as a spiritual test (sabar) or supernatural influence (saya), often suppressing their feelings to preserve izzat (family honor). Most relied on spiritual healers (pirs) and religious rituals before considering clinical support, which remained inaccessible due to cost, distance, male guardianship requirements, and stigma. Elder female relatives were frequently complicit in denying PPD as legitimate. Economic pressures, especially related to the birth of daughters and dowry anxieties, compounded the psychological toll. The study highlights the inadequacy of biomedical models in such contexts and underscores the need for culturally sensitive, community-based mental health interventions rooted in local language, metaphors, and belief systems.

Keywords

• Postpartum depression; Cultural stigma; Maternal mental health.

Citation

Rashid MK, Mir JN (2025) The Silent Struggle: How Women Experience and Conceal Postpartum Depression. JSM Women’s Health 5(1): 1014.

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a significant yet often overlooked mental health condition affecting mothers worldwide. While biomedical literature identifies hormonal shifts, birth trauma, and psychological vulnerability as contributing factors [1], growing evidence suggests that sociocultural environments fundamentally shape how PPD is experienced, understood, and managed [2]. In many non-Western contexts including South Asia, postpartum distress is not only underdiagnosed but also linguistically and spiritually reinterpreted, contributing to its concealment. This study focuses on the lived experiences of PPD among women in Layyah and Taunsa, two deeply patriarchal, under-resourced districts in South Punjab, Pakistan, where emotional suffering is frequently spiritualized, suppressed, or ignored.

Globally, PPD affects an estimated 10–20% of new mothers, but rates are higher in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), often reaching 30–40% in underserved populations [3]. In Pakistan, prevalence estimates vary between 28% and 63%, with rural areas reporting higher figures due to limited mental health services, high fertility rates, gender-based restrictions, and deep-rooted stigma [4,5]. Yet despite this, little is known about how women themselves make sense of their distress, particularly in Saraiki-speaking, agrarian communities where traditional beliefs about motherhood, morality, and mental illness dominate. The “sacrificial mother” archetype which idealizes silence, endurance, and self-denial often compels women to suppress emotional pain, reinforcing structural and interpersonal neglect [6].

In such settings, maternal sadness is frequently attributed to spiritual causes such as evil eye (nazar), supernatural interference (saya), or patience test by God (sabar). These idioms of distress are not simply symbolic but serve as cultural scripts that allow women to articulate suffering without violating norms of maternal strength and religious virtue [7]. As a result, emotional disclosure becomes a risk to personal honor (izzat) and family reputation. Previous studies in Pakistan have found that women often delay seeking help for PPD by several months, with some never receiving formal support at all [8]. This is exacerbated by dependency on male guardians for mobility, lack of female healthcare providers, and the absence of culturally relevant screening tools.

This silence is further reinforced by family dynamics. In joint family systems, the authority of elder female relatives particularly mothers-in-law is often central to postnatal care decisions. While these figures may provide logistical support, they also police emotional expression, dismissing sadness as weakness or laziness [9]. In the absence of safe emotional spaces, women often turn to faith healers(pirs), amulets (taweez), and recitation of Quranic verses as coping mechanisms. However, reliance on these remedies often delays access to formal care and can contribute to the chronicity of untreated depression [10]. Despite the central role of traditional healing in many rural Pakistani communities, its efficacy in addressing complex maternal mental health disorders remains unproven [11].

In addition to spiritualization, poverty emerged as a critical amplifier of distress. Most participants in this study belonged to low-income households struggling with food insecurity, health expenses, and inflation. These economic stressors were compounded by the birth of daughters, which for many families in South Punjab, signalled future dowry obligations and increased financial burden [12]. This gendered financial anxiety adds an intergenerational and cultural weight to the postpartum experience, making depression not only a matter of mood but of perceived maternal failure.

While global PPD research is growing, much of it remains clinically focused and Western-centric, often ignoring the sociocultural and spiritual contexts of rural women in South Asia. By centering the voices of women in Layyah and Taunsa, this study seeks to explore how PPD is narrated, concealed, and negotiated within local cultural frameworks. It asks: How do women in rural South Punjab experience postpartum depression, and what factors compel them to hide or spiritualize their suffering? In doing so, it contributes to a culturally grounded understanding of maternal mental health, offering insights for more responsive, decolonized, and context-specific care models.

METHODOLOGY

This study employed a qualitative, phenomenological research design to explore how women in Layyah and Taunsa, South Punjab, experience and conceal postpartum depression (PPD). A phenomenological approach was chosen to capture the rich, lived emotional realities of participants and understand how cultural, social, and spiritual meanings shape their interpretation of psychological distress [13].

The research was conducted in two predominantly rural districts Layyah and Taunsa, located in South Punjab, Pakistan. This region is characterized by low literacy rate, limited maternal healthcare access, and multigenerational joint family structures, making them ideal settings to investigate sociocultural dynamics of maternal mental health.

A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit 32 postpartum women aged 20 to 42 years who had given birth within the last three years. Participants were recruited through local Lady Health Workers (LHWs), informal referrals within community health centers and Snowball sampling through prior interviewees. All participants self-identified as Muslim, and 88% resided in joint family systems, enhancing cultural homogeneity. Inclusion criteria required that participants; had experienced emotional or psychological distress during postpartum and are willing to share their experiences in Saraiki or Urdu.

Data was collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews, conducted between October 2022 and March 2023. Interviews were conducted in the participants’ native language (Saraiki or Urdu) and lasted 30-45 minutes. A flexible interview guide was used, covering; emotional and physical symptoms, social support and cultural interpretations, barriers to expression and help seeking, use of spiritual or traditional healing, perceptions of mental illness and stigma. All interviews were with verbal and written consent. Ethical clearance was obtained from the NAEC Taunsa.

NVivo software was used to support coding and theme development. Coding was inductively grounded in the data, while interpretations were contextualized in cultural discourse. To enhance credibility and trustworthiness, the following steps were taken; peer debriefing sessions with qualitative researchers member checking with a subset of participants and reflexive journaling to track researcher bias.

RESULTS

This qualitative study explored the lived experiences of postpartum depression (PPD) among 32 women residing in the rural districts of Layyah and Taunsa, South Punjab, Pakistan. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 42 years (mean age: 28) and were mothers of children aged between 2 months and 3 years. Most participants (75%) came from low-income households, and the remaining 25% from lower-middle-class backgrounds. All identified as Muslim, and the vast majority (88%) lived within multigenerational joint family systems. Through thematic analysis, five central themes emerged: (1) cultural silence and spiritualization of distress, (2) gendered barriers to expression, (3) healthcare access challenges, (4) traditional coping vs. medical neglect, and (5) economic hardship as an emotional amplifier.

Cultural Silence and the Spiritualization of Emotional Distress

Across the sample, emotional struggles were overwhelmingly framed not in medical or psychological terms, but through spiritual, religious, or supernatural explanations. Every participant avoided the clinical label “depression.” Instead, distress was attributed to “evil eye,” spiritual weakness, or divine trials:

“This was not a ‘disease’ it was saya (shadow) from evil eye or Allah’s test of my sabar (patience).” Participant 09 (Age 33, Layyah)

This framing often led to spiritual gatekeeping of emotional expression. Several women internalized cultural beliefs linking maternal sadness with harming the child:

“My mother-in-law said sad mothers make ‘poison milk.’ So I smiled while feeding my baby, even when I wanted to scream.” Participant 14 (Age 24, Taunsa)

Notably, 69% (22 women) attributed their psychological symptoms to weak faith or moral failure, causing help seeking delays ranging from 8 to 14 months.

Gendered Barriers to Emotional Expression

PPD symptoms were tightly constrained by patriarchal family systems that suppressed open communication, especially regarding emotional vulnerability.

- Decision-making dependency: 28 out of 32 women required explicit permission from a male guardian (mehram) to access health services.

- Fear of stigma: 94% of participants reported avoiding disclosure due to the fear of being labeled pagal (mad) or unstable, a label that could justify marital conflict or even abandonment.

“If I told my husband about my tears, he said, ‘My mother bore 10 children without complaints.’ How could I disgrace his family?” Participant 27 (Age 30, Layyah)

Such remarks demonstrate the intergenerational policing of emotional expression, which equated silence with strength and endurance with maternal virtue.

Systemic Barriers to Mental Health Access

This theme highlights how infrastructure gaps, gender norms, and poverty intersected to hinder clinical help seeking.

Participants were effectively locked out of formal mental healthcare, reinforcing isolation and reliance on informal strategies (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1: Systemic Barriers to Mental Health Access.

|

Barrier |

Prevalence |

Example |

|

Lack of female healthcare providers |

68% |

“The male doctor at Basic Health Unit asked, ‘Why are you sad?’ I couldn’t discuss private pains with him.” (P05) |

|

Distance from facilities |

81% |

“The nearest clinic is 25 km away. No bus, no mehram to accompany me, how could I go?” (P18) |

|

High cost of private care |

63% |

“Private clinics charge 1,500 PKR per visit, that’s a week’s wheat ration.” (P22) |

Table 2: Themes and Prevalence

|

Theme |

Prevalence |

Subthemes |

|

Cultural Spiritualization of Distress |

100% |

Saya, evil eye, tests of sabar, taweez, faith-based meanings |

|

Gendered Silencing and Stigma |

94% |

Fear of being labeled pagal, male permission needed |

|

Structural Barriers to Healthcare |

81% |

Distance, lack of transport, cost, lack of female doctors |

|

Reliance on Traditional Healing |

78% |

Pirs, Quranic healing, folk medicine |

|

Emotional Suppression in Joint Families |

88% |

Pressure from in-laws, multigenerational expectations |

|

Economic Stress as Amplifier |

92% |

Inflation, food insecurity, daughter- related despair |

|

Clinical Support Accessed |

19% |

Often moralized, spiritualized, or dismissed |

Traditional Coping vs. Medical Neglect

In the absence of accessible or sensitive healthcare, women turned to traditional and religious coping mechanisms.

- Spiritual remedies: 78% visited pirs (faith healers), wore taweez (amulets), or engaged in recitation of Quranic verses.

- Home-based folk healing: 59% used desi totkay (recipes), including sattu (barley drink), herbal infusions, and massage.

“The Dai massaged me with mustard oil and said sadness would ‘melt away.’ It didn’t.”

Participant 11 (Age 29, Layyah)

Only 6 out of 32 women (19%) accessed any form of formal care—and even then, their symptoms were often minimized or moralized:

“The Lady Health Worker said, ‘Pray more, Allah rewards mothers.’ She never mentioned depression.” Participant 31 (Age 26, Taunsa)

This pattern reveals a systemic failure to recognize PPD within the rural maternal healthcare discourse.

Economic Pressure as a Psychological Trigger

Poverty was not just background context; it was a primary driver of postpartum anxiety. About 92% of participants described deep fear around their ability to provide food, shelter, and medicine for their infants, especially amid rising inflation. Gendered economic stress was particularly pronounced among mothers of girls. 7 out of 12 mothers with newborn daughters reported immediate despair, often citing dowry obligations:

“When I saw my baby was a girl, I cried for 3 days. How will I afford her wedding? My in-laws blame me.” Participant 08 (Age 21, Taunsa)

In these accounts, emotional distress was closely tied to social disempowerment and financial precarity, showing that any intervention must be economically and culturally embedded.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals how women in the rural districts of Layyah and Taunsa, Pakistan, experience Postpartum Depression (PPD) through a cultural lens where spiritualization, patriarchy, and systemic healthcare neglect intersect. PPD was almost universally interpreted not as a medical disorder but as a test of sabar (patience) or the result of evil forces (saya). This aligns with findings in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where 89% of rural women attributed postpartum sadness to weak faith or supernatural causes rather than psychological distress [8].

Such framing compels women to suppress emotions to protect family honor (izzat). The invisibility of distress here mirrors what Husain et al. [6], described as the “sacrificial mother archetype” in South Asia, a cultural expectation that elevates suffering as maternal virtue. This pattern contrasts with communities like Kerala, India, where matrilineal norms buffer women’s emotional expression, reducing internalized stigma [14].

One striking barrier was the requirement for male permission (mehram) to access health facilities, reported by 88% of participants. This replicates findings from Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, where mental illness remains cloaked in religious silence. However, our findings are distinct in highlighting how mothers-in-law, rather than husbands, often served as emotional gatekeepers echoing [9], Karachi based study, where 74% of women were discouraged by elder female relatives from acknowledging PPD.

Structural constraints were equally dire. The absence of female providers in 68% of cases and the long distances to health units mirror challenges reported in rural Ethiopia and Bangladesh [4-15]. However, Punjab’s reliance on Lady Health Workers (LHWs), often undertrained in mental health contrasts with Brazil’s community health model, which includes PPD-specific training [16-18]. The limited impact of the LHWs system was evident as most women reported being advised to “pray more” rather than seek psychological care.

A critical insight was the dominance of traditional and spiritual coping. Around 81% of participants sought help from pirs (faith healers) before considering formal care, a pattern also seen in Sindh [10]. In contrast, urban Lahore women preferred psychiatric consultation [5], revealing a clear urban-rural disparity in explanatory models and access.

The theme of dowry-driven despair, particularly among mothers of daughters, was deeply revealing. Seven participants reported crying or emotional breakdowns upon the birth of a girl due to financial anxiety over dowry. This supports Asif et al. [12], who linked daughter aversion with maternal depression in South Punjab. While countries like Vietnam also shows son preference, the practice of prenatal dowry planning reported by 58% of women in our sample is a uniquely under-researched feature of postnatal financial trauma in South Asia.

From a methodological perspective, the use of Saraiki language emotion cards provided culturally resonant entry points into conversations about unspoken pain. This technique aligns with Kirmayer et al.’s [7], call for cultural idioms of distress rather than Western scales like the Edinburgh PPD tool. Yet, 78% of participants found taweez (amulets) and faith-based rituals ineffective, complicating Kleinman’s, et al. [11], thesis that cultural healing practices inherently promote recovery.

Practical Implications

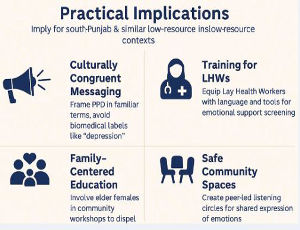

The findings of this study have significant implications for public health policy, maternal mental healthcare delivery, and culturally tailored interventions in Pakistan and similar low-resource settings. First, the spiritual framing of depression and the dominance of religious idioms such as sabar, saya, and taweez indicate that conventional mental health messaging may fail to resonate unless it integrates culturally congruent language and acknowledges these belief systems. Health campaigns and communication materials should use locally relevant metaphors and avoid direct pathologizing terms like “depression,” instead engaging concepts such as “emotional exhaustion” or “inner heaviness.”

Second, the study highlights the urgent need to train Lady Health Workers (LHWs) in basic psychological first aid and maternal mental health screening. Given their proximity to rural women, LHWs are well-positioned to identify distress but currently lack the language, tools, and knowledge to intervene meaningfully. Developing Saraiki language screening aids, visual tools, and short training modules could substantially enhance their efficacy (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Practical Implications.

Third, family and community-level interventions are essential. As mothers-in-law and elder women serve as emotional gatekeepers, involving them in community awareness workshops about postpartum emotional health could help dismantle intergenerational stigma. Additionally, creating safe, peer-led listening circles at health units or village centers would provide women with an outlet to share their experiences in a judgment-free, culturally respectful environment.

Limitations

This study, while methodologically rigorous, has several limitations. First, the use of convenience and snowball sampling may have excluded women who are entirely isolated, severely depressed, or those unwilling to engage due to cultural shame, potentially skewing the findings toward those slightly more open to discussing their emotions. Second, all interviews were conducted in Saraiki or Urdu and translated into English, which may have introduced subtle shifts in meaning despite careful bilingual transcription.

Third, the study was limited to two rural districts Layyah and Taunsa, and may not fully represent the diversity of postpartum experiences across Pakistan’s other cultural, linguistic, or sectarian contexts. Furthermore, no healthcare providers or family members were interviewed, meaning the broader ecosystem of influence around the mothers remains unexplored. Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not capture the evolution of PPD over time, nor does it track recovery trajectories.

Recommendations

Based on the study’s findings, the following recommendations are proposed: Integrate Maternal Mental Health in Primary Care embed mental health screening within maternal and child health visits at Basic Health Units (BHUs), using culturally adapted tools. LHWs Mental Health Training provide Lady Health Workers with short, practical training on recognizing emotional distress and offering basic psychosocial support. Development of culturally sensitive communication materials e.g. audio visual resources in Saraiki and Urdu to raise awareness about PPD, utilizing metaphors and idioms women relate to. Community-based peer support establishment at village-level listening spaces or women’s circles led by trained peer facilitators where emotional sharing is normalized. Family engagement programs focused on intergenerational education sessions targeting mothers-in law and spouses to encourage empathy and reduce stigma.

Based on the study’s findings, the following recommendations are proposed: Integrate Maternal Mental Health in Primary Care embed mental health screening within maternal and child health visits at Basic Health Units (BHUs), using culturally adapted tools. LHWs Mental Health Training provide Lady Health Workers with short, practical training on recognizing emotional distress and offering basic psychosocial support. Development of culturally sensitive communication materials e.g. audio visual resources in Saraiki and Urdu to raise awareness about PPD, utilizing metaphors and idioms women relate to. Community-based peer support establishment at village-level listening spaces or women’s circles led by trained peer facilitators where emotional sharing is normalized. Family engagement programs focused on intergenerational education sessions targeting mothers-in law and spouses to encourage empathy and reduce stigma.

CONCLUSION

This study sheds light on the complex and often hidden experience of postpartum depression among rural women in Layyah and Taunsa. Far from being merely a biomedical condition, PPD in these settings is deeply intertwined with spiritual beliefs, gendered family hierarchies, and economic hardship. Women conceal their distress to preserve familial honor, navigate social expectations, and avoid stigma, often turning first to spiritual solutions and delaying formal care.

These findings underscore the urgency of rethinking maternal mental health strategies in Pakistan through culturally grounded, community-based models. Silence and suffering cannot be addressed by clinical tools alone, they require empathic listening, cultural fluency, and systemic change. Recognizing and validating the emotional lives of mothers is not just a health imperative, it is a human rights obligation.

Authors Contribution

Author 1: Basic Idea, Design, Methodological work, Literature work, Writing and formatting, Contributed to Write the Introduction, Risks assessment, Adaptation Strategies, and Policy Response

Author 2: Basic Research Idea, Literature work, contributed to write Risk Assessment, contributed to write Adaptation Strategies, Policy Response and Methodological work.

Funding: Self-funded project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declares that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper. The research was conducted independently, and there are no financial or personal relationships with individuals or organizations that could have inappropriately influenced the content of this study.

REFERENCES

- Stewart DE, Vigod SN. Postpartum Depression: Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Emerging Therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2019 27; 70: 183-196.

- Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006; 33: 323-331.

- Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012; 90: 139G-149G.

- Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol Med. 2003; 33: 1161-1167.

- Ali F, Raza M, Imran N. Urban women’s experiences of postpartum depression in Lahore. Pakistan J Med Res. 2022; 21-28.

- Husain F, Khan A, Rizvi N. Sacrificial mother archetypes in South Asia: A barrier to maternal mental healthcare. Asian J Psychiatr. 2012; 261-265.

- Kirmayer LJ, Rousseau C, Jarvis G. Cultural idioms of distress in mental health. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2021; 173-186.

- Rehman F, Shah Z, Ullah A. Beliefs and barriers in postpartum depression among rural women in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan J Public Health. 2021; 12-16.

- Shaikh S, Fatima R, Hassan M. Elder family members as barriers to mental health disclosure in postpartum women. Karachi J Psychiatr. 2021; 34-41.

- Khalid R, Shah A, Siddiqui H. Understanding postpartum depression in Sindh: From spiritual healing to psychiatry. Ann Mental Health. 2023; 99-108.

- Kleinman A. Rethinking Psychiatry: From Cultural Category to Personal Experience. Free Press. 2018

- Asif M, Fatima S, Qureshi M. Maternal depression and gender preference in South Punjab. Int J Social Psychiatr. 2020; 498-507.

- Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. 2016.

- Pillai A, Jayashree K, Prasad J. Cultural buffering of postpartum distress in matrilineal Kerala. Indian J Social Psychiatr. 2020; 135- 141.

- Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A. Perinatal mental health in Ethiopia: Systemic failures and sociocultural silencing. Reproductive Health Matters. 2020; 41-54.

- Lancetti A, Pereira C, Fernandes T. Brazil’s family health strategy and maternal mental health: Lessons from integrated community care. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil. 2021; 913-920.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. 1985

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006; 77-101.