Cobalamin Deficiency and Cognitive Decline: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Evidence

- 1. Department of Internal Medicine and Geriatry, University Hospitals of Strasbourg (Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, HUS), France

Abstract

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) has long been implicated in cognitive health. Observational associations between low B12, elevated Methylmalonic Acid (MMA) or Homocysteine (Hcy), and cognitive decline have motivated trials of supplementation. The clinical picture is complex. Biochemistry links B12 to methylation, myelin maintenance, and neurotransmitter synthesis. Observational cohorts show consistent associations between low B12 biomarkers and accelerated cognitive decline or dementia risk. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) of B12 or B-vitamin combinations show mixed results. Selected trials in high-risk subgroups or trials that reduced brain atrophy reported positive effects. Large pragmatic trials in unselected older populations generally did not demonstrate clinically meaningful cognitive benefit. Diagnostic testing is imperfect, and functional deficiency can exist despite “normal” serum B12. Treatment is safe and corrects hematological and some metabolic abnormalities, but neurological recovery is variable and often partial if treatment is delayed. Recent mechanistic and imaging data suggest that benefit is most likely when supplementation is applied early, in subjects with biochemical deficiency or elevated Hcy, and perhaps Highlights when co-factors (folate, B6, omega-3 fatty acids) are adequate. This review synthesizes biochemical, epidemiological, clinical, interventional, diagnostic, and therapeutic evidence and outlines priorities for research and practice.

• Vitamin B12 deficiency is a frequent, underdiagnosed condition in older adults and a reversible cause of neurological impairment.

• The relationship between vitamin B12 status and cognitive decline remains controversial; recent evidence challenges the belief in a direct causal link.

• Elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid are stronger predictors of cognitive impairment than serum B12 concentration alone.

• Interventional trials show that B12 supplementation improves cognition only in truly deficient individuals, not in the general elderly population..

• Future research should focus on functional biomarkers and combined nutritional-neurovascular pathways rather than isolated vitamin supplementation.

Keywords

• Vitamin B12 Deficiency; Cognitive Decline; Alzheimer’s Disease; Homocysteine; Neurodegeneration; Elderly Population

Citation

Andres E, Vogel T, Lorenzo-Villalba N (2025) Cobalamin Deficiency and Cognitive Decline: Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Evidence. J Aging Age Relat Dis 4(1): 1008.

INTRODUCTION

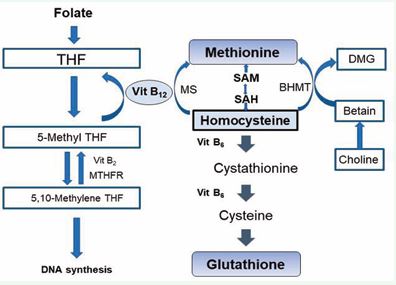

Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) is biochemically unique. It is required for two essential enzymatic reactions in humans: (i) methionine synthase (methylcobalamin) that remethylates Homocysteine (Hcy) to methionine and sustains S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) dependent methylation, and (ii) methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (adenosylcobalamin) that converts methylmalonyl CoA to succinyl-CoA [1-3]. These reactions underpin DNA synthesis, myelin maintenance, and multiple metabolic pathways implicated in neuronal integrity [2-4]. Epidemiological studies over decades linked low B12 or functional markers (elevated Methylmalonic Acid [MMA], Homocysteine [Hcy]) with cognitive impairment, brain atrophy, and increased dementia risk [5-7]. These data generated a widely held clinical belief that routine B12 supplementation could prevent or slow cognitive decline. Randomized trials later tested this hypothesis but produced mixed and sometimes contradictory results [8 11]. The purpose of this article is to reconcile mechanistic plausibility, observational associations, and interventional evidence, and to identify when B12 supplementation is likely to be effective for cognition. We review metabolism and pathophysiology, epidemiology, clinical phenotypes, cohort and trial evidence, diagnostic strategies, treatment modalities, outcomes, and future directions. Metabolism and pathophysiology of vitamin B12 Vitamin B12 absorption and cellular utilization are complex. Dietary cobalamin is liberated in the stomach and bound to Intrinsic Factor (IF) produced by gastric parietal cells; the IF-B12 complex is absorbed in the ileum via cubam receptors (complex of cubiline and amnionless [2-12]. Transport in plasma depends on Transcobalamin (TC) II (also named Holotranscobalamin [holoTC]) and Haptocorrin (TC I and III); holoTC represents the fraction available to cells. Intracellularly, B12 serves as cofactor for methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase; deficiency causes accumulation of Hcy and MMA, reduced SAM, impaired methylation reactions, disrupted phospholipid and myelin synthesis, and increased oxidative stress [3-12]. In the brain, these biochemical derangements translate into demyelination, synaptic dysfunction, mitochondrial impairment, neuro-inflammation, and neuronal loss [2-13]. Elevated Hcy itself is vaso- and neuro-toxic: it promotes endothelial dysfunction, oxidative injury, excitotoxicity, and prothrombotic states that can produce white matter lesions and ischemic injury [14,15]. The interplay of direct neurochemical injury and indirect vascular injury provides a coherent mechanistic rationale linking B12 deficiency to both neurodegeneration and vascular cognitive impairment [1-16] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Mechanisms linking Vitamin?B12 deficiency to cognitive decline. Folate (vitamin B9) is converted to Tetrahydrofolate (THF) and subsequently to 5,10-methylene THF via MTHFR and vitamin B2-dependent reactions. 5-methyl THF donates a methyl group to homocysteine, a reaction catalyzed by methionine synthase (MS) with vitamin B12 as a cofactor, regenerating methionine. Methionine is converted to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor, which cycles to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) and back to homocysteine. Homocysteine can also be remethylated via betaine homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) using choline-derived betaine or converted to cystathionine and cysteine through the vitamin B6-dependent transsulfuration pathway, ultimately forming glutathione. Disruptions in these pathways due to B12, folate, or B6 deficiency result in elevated homocysteine, impaired methylation, reduced DNA synthesis, oxidative stress, and increased risk for vascular and neurocognitive disorders.

Epidemiology of vitamin B12 deficiencies Population studies report that overt B12 deficiency (markedly low serum B12 with clinical signs) is uncommon in middle-aged adults but rises with age: 5% to 60% in institutionalized elderly patients. Prevalence estimates vary with biomarker definitions; using combined indicators (serum B12, holoTC, MMA, Hcy) identifies more subclinical cases than serum B12 alone. Community cohorts find that low B12 biomarkers and elevated Hcy are common among older adults and are associated with greater rates of cognitive decline and higher dementia risk [5-7]. Prospective data indicate that lower holoTC or higher MMA/Hcy predict faster cognitive deterioration over 3–10 years [5]. Geographic and dietary patterns influence prevalence; vegetarians and vegans without supplementation, people after bariatric surgery, and patients on metformin are at elevated risk [2-17]. Importantly, many studies show graded associations: risk increases as functional markers worsen, even within ranges traditionally considered “low-normal,” which has fueled debate about optimal thresholds for cognitive protection [7-18].

Clinical presentation of vitamin B12 deficiency

Clinical manifestations of B12 deficiency span hematological and neurological domains. Classic hematological features include macrocytic anemia, hypersegmented neutrophils, and, in severe cases, pancytopenia [19]. Neurologically, B12 deficiency produces a spectrum from peripheral neuropathy to the syndrome of combined degeneration of the spinal cord (posterior and lateral columns), gait disturbance, and cognitive symptoms ranging from subtle executive dysfunction and slowed processing to frank dementia [2-13] (Table 1). Neuropsychiatric presentations include depression, apathy, and psychosis in rare cases [13]. Cognitive impairment may precede hematological signs. Moreover, B12-related cognitive dysfunction can mimic Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia, since both white matter changes and cortical atrophy have been reported in association with low B12 status [3-20]. Clinical reversibility is time-dependent; hematological abnormalities often resolve promptly with treatment, whereas neurological recovery is slower and incomplete if therapy is delayed [2].

Table 1: Neuropsychiatric manifestations of vitamin B12 deficiency.

|

Manifestation |

Description / Notes |

|

Peripheral neuropathy |

Paresthesia, numbness, tingling, or “pins and needles,” usually in a glove-and-stocking distribution |

|

Subacute combined degeneration (SCD) |

Demyelination of dorsal columns and corticospinal tracts → impaired vibration & position sense, spasticity, weakness |

|

Gait disturbances / ataxia |

Due to sensory loss and impaired proprioception |

|

Cognitive changes |

Memory loss, confusion, dementia-like symptoms, decreased attention |

|

Mood disorders |

Depression, irritability, apathy |

|

Psychosis / hallucinations |

Rare, may occur in severe deficiency |

|

Optic neuropathy |

Visual disturbances, sometimes leading to vision loss |

|

Autonomic dysfunction |

Rare; can include orthostatic hypotension or urinary disturbances |

Causes of vitamin B12 deficiencies

Vitamin B12 deficiency arises from a wide spectrum of nutritional, gastrointestinal, and systemic causes that impair its absorption, transport, or utilization [21]. Because vitamin B12 is obtained almost exclusively from animal-derived foods and requires multiple specific carrier proteins for absorption, disruptions at any step of this pathway can lead to deficiency. Table 2 presents the main causes of vitamin B12 deficiencies in adults and elderly patients [21].

LINKS BETWEEN VITAMIN B12 AND COGNITION

Vitamin B12 deficiency is a frequent yet often underrecognized condition in aging populations, with reported prevalence ranging from 6% in community dwelling adults to nearly 20% among individuals over 60 years of age. In dementia cohorts, the burden remains significant, with studies reporting deficiency rates between 7–10%, while longitudinal data suggest a cumulative incidence of approximately 7% over three years in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [1-3]. The relationship between vitamin B12 status and cognitive decline has been extensively investigated, though findings remain heterogeneous. Observational studies and meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated that low or borderline B12 concentrations—particularly when assessed using functional biomarkers such as methylmalonic acid or holotranscobalamin—are associated with poorer cognitive performance and increased risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease [4-9]. However, evidence from interventional trials suggests that vitamin B12 supplementation does not significantly slow cognitive decline in non-deficient individuals, highlighting that the association may reflect a marker of underlying metabolic or vascular dysfunction rather than a direct causal link [7-14]. Overall, while vitamin B12 deficiency remains a modifiable factor contributing to neurocognitive impairment in older adults, its role in the pathogenesis or progression of Alzheimer’s disease appears limited to cases of overt biochemical deficiency rather than marginal status.

|

Category |

Etiology / Cause |

Mechanism / Notes |

|

Impaired Absorption |

Pernicious anemia (Biermer’s disease) |

Autoimmune gastritis with antibodies against intrinsic factor; one of the common cause in developed countries |

|

|

Food-cobalamin malabsorption (FCM) |

Due to atrophic gastritis, H. pylori infection, partial gastrectomy/gastric bypass, pancreatic insufficiency, or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO); one of the common cause in developed countries |

|

|

Ileal diseases or resection |

Includes celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or surgical removal of the terminal ileum |

|

|

Genetic disorders |

Transcobalamin or receptor defects (e.g., Immerslund-Gräsbeck’s disease) |

|

Inadequate Intake |

Dietary insufficiency |

Low consumption of animal-source foods; common in strict vegetarians, vegans, and infants of vegan mothers |

|

Increased Requirements |

Physiological demand |

Pregnancy, lactation, rapid growth—may increase B12 needs |

|

Drug-Induced |

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) |

Reduce gastric acid → decreased release of B12 from food (responsible for FCM) |

|

|

H2-receptor antagonists |

Similar mechanism as PPIs (responsible for FCM) |

|

|

Metformin |

Interferes with calcium-dependent B12 absorption in the ileum (responsible for FCM) |

|

Other Causes |

Nitrous oxide exposure |

Inactivates vitamin B12; increasingly seen with recreational use, especially in adolescents |

Data from epidemiological studies

Longitudinal cohort studies consistently associate low B12 biomarkers and elevated Hcy with accelerated cognitive decline, greater brain atrophy, and higher incidence of dementia [5-7] (Table 3). For example, a large prospective analysis showed that low holoTC and high MMA predicted faster cognitive decline across multiple domains [5]. Observational imaging studies link elevated Hcy and low B12 to increased white matter hyperintensities, greater ventricular enlargement, and cortical atrophy—changes that portend cognitive decline [6-20]. Meta-analytic syntheses of prospective data found that elevated Hcy confers increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, and that low B12 status correlates with poorer performance on cognitive tests [17-22]. These associations are robust across populations but are susceptible to residual confounding and reverse causation (illness-related poor intake), making causality difficult to assert from observational data alone [16-22].

Table 3: Epidemiological studies linking vitamin B12 status and cognitive function.

|

Study (year) |

Design |

Population |

Main findings |

Conclusion |

|

Moore et al., 2012 |

Meta- analysis |

14,000 participants |

Low B12 linked to poorer cognitive performance |

Association not causal |

|

O’Donnell et al., 2020 |

Cross- sectional |

5,018 elderly |

Low B12 + high folate → lower MMSE scores |

Functional deficiency relevant |

|

Smith et al., 2022 |

Review |

43 studies |

B12 deficiency correlates with dementia risk |

Supplementation helps only in deficient |

|

Clarke et al., 2014 |

RCT |

2,919 older adults |

B12 supplementation ↓ homocysteine but no cognitive benefit |

No prevention effect |

Data from interventional studies

Randomized trials testing B12, folate, and B6 supplementation have yielded heterogeneous results (Table 4). Trials in unselected older adults frequently showed little cognitive benefit despite reductions in Hcy [8-11]. By contrast, well-designed trials in selected high- risk groups reported positive findings. The VITACOG randomized trial in older adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) demonstrated that B-vitamin treatment (folate, B12, B6) that substantially lowered Hcy slowed the rate of whole-brain atrophy and cognitive decline, particularly in subjects with elevated baseline Hcy; effects were amplified in individuals with adequate omega-3 fatty acid status [19]. The FACIT folic acid trial reported improved cognitive domains after 3 years of folate supplementation in older adults with high Hcy [22]. Meta- analyses of RCTs conclude that homocysteine-lowering with B vitamins lowers Hcy reliably but produces modest or no average cognitive benefit across heterogeneous study populations; however, subgroup analyses suggest benefit in participants with MCI, high baseline Hcy, or when trials targeted brain atrophy outcomes [8-16]. Methodological issues—short follow-up, inclusion of participants unlikely to respond, low baseline deficiency prevalence, and variable dosing—explain much heterogeneity.

Table 4: Interventional trials evaluating vitamin B12 supplementation and cognition.

|

Trial |

Design & Duration |

Population |

Intervention |

Outcome |

Conclusion |

|

FACIT Trial (Ford et al., 2010) |

RCT, 2 years |

Older adults (n=818) |

B12 + folate |

↓ homocysteine, no cognitive benefit |

Limited effect |

|

VITACOG (Smith et al., 2010) |

RCT, 2 years |

MCI patients (n=271) |

B12 + folate + B6 |

↓ brain atrophy, improved memory |

Benefit in elevated Hcy |

|

Walker et al., 2012 |

RCT, 18 months |

Older adults |

B12 supplementation |

No cognitive improvement |

No benefit in non-deficient |

|

Clarke et al., 2014 |

RCT, 2 years |

Elderly |

B12 + folate |

↓ homocysteine, unchanged cognition |

Supports selective supplementation |

Cognitive and structural brain effects are inconsistent: pooled RCTs in unselected older adults show no clinically meaningful mean cognitive benefit, whereas targeted studies in MCI or subjects with elevated Hcy show slowing of brain atrophy and cognitive decline [3-16]. Meta-analyses indicate that the magnitude of cognitive benefit depends on baseline biochemical status, clinical phenotype (MCI vs. normal cognition), trial duration, and co-nutrient status such as omega-3 fatty acids [3-19]. These nuanced results suggest that the “myth” of universal cognitive benefit from B12 supplementation is unsupported, but that targeted supplementation in biochemically and clinically selected individuals can be disease-modifying.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH FOR DIAGNOSIS VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY

Diagnosis of B12 deficiency for cognitive purposes requires a combination of clinical assessment and biomarkers. Serum total B12 alone is insensitive and can be misleading. Functional biomarkers such as MMA and tHcy, and holoTC improve diagnostic accuracy [21-23]. Combined indices (e.g., “cB12”) integrate multiple markers and outperform single tests. Neuroimaging (MRI) often reveals white matter hyperintensities, cortical atrophy, or spinal cord changes in severe cases, but these findings are not specific [20]. Given the imperfect tests, clinical context is critical: older adults with cognitive decline, gait disturbance, neuropathy, or unexplained anemia warrant comprehensive B12 assessment, including MMA or holoTC [2-13]. Thresholds for intervention remain debated; some investigators argue for treating “low-normal” values when clinical suspicion exists because functional deficiency can occur below conventional cutpoints [7-23].

TREATMENT OF VITAMIN B12 DEFICIENCY IN CASE OF COGNITIVE DECLINE

Treatment strategies for B12 deficiency include parenteral and high-dose oral supplementation. Intramuscular hydroxocobalamin or cyanocobalamin remains standard for severe neurologic disease or proven malabsorption; common regimens begin with frequent injections followed by maintenance monthly dosing (1 mg/ day for one week, than 1mg/week for one month, than 1 mg each month) [2-23]. Higher doses is proposed by several teams (2-5 mg/day). High-dose oral cyanocobalamin (e.g., 1–2 mg/day) is effective in many cases including some with absorption defects, due to passive diffusion [2-23]. Combination therapy with folic acid and B6 is commonly used when trials are designed to lower Hcy, but folate alone can mask hematologic signs and is not a substitute for B12 [19]. Safety of B12 therapy is excellent. Treatment of metabolic abnormalities (MMA, Hcy) occurs rapidly; neurological improvement is variable and depends on timing and severity [2-19]. Supplementation protocols in trials have varied widely, complicating comparisons across studies.

PERSPECTIVES

Future research should prioritize precision in participant selection, biomarker use, and outcome measures. Trials should enroll participants with documented functional B12 deficiency or elevated Hcy, or those with MCI, and should ensure adequate duration and power to detect clinically meaningful change [7-16]. Imaging biomarkers, such as rates of regional atrophy and white matter integrity, are sensitive endpoints and may reveal treatment effects not captured by cognitive tests in short trials [2]. Mechanistic studies combining metabolomics, epigenomics, and neuroimaging can clarify pathways linking B12 to neurodegeneration and identify responders [13-24]. Interactions with other nutrients (folate, B6, omega-3 fatty acids) and genotypes (MTHFR polymorphisms) merit rigorous evaluation and could inform combination therapies [3-19]. From a public health perspective, improving detection of functional B12 deficiency in older adults and high-risk groups remains a priority because timely supplementation prevents irreversible neurological injury even if dementia prevention remains uncertain [2-18].

CONCLUSION

Vitamin B12 is biologically central to neuronal health, and deficiency causes biochemical, structural, and clinical brain injury. Observational evidence consistently links low B12 status and elevated Hcy to cognitive decline and dementia. Randomized trials show that routine supplementation in unselected older adults does not produce clear cognitive benefit. However, targeted supplementation in high-risk or biochemically deficient individuals, and interventions that lower Hcy in MCI, slow brain atrophy and in some studies reduce cognitive decline. The simplistic claim that B12 supplementation universally prevents dementia is untenable. The pragmatic clinical message is twofold: (i) screen and treat true or functional B12 deficiency promptly to prevent irreversible neurologic damage; and (ii) reserve recommendations for routine supplementation to prevent cognitive decline to contexts supported by trial evidence—namely, subjects with biochemical deficiency, elevated Hcy, or established MCI—while further precision medicine trials are pursued.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely thank all clinicians and researchers of the CARE B12 group at the University Hospitals of Strasbourg (Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, HUS) for their invaluable contributions to the research and data collection.

REFRENCES

- Halczuk K, Ka?mierczak-Bara?ska J, Karwowski BT, Karma?ska A, Cie?lak M. Vitamin B12-Multifaceted In Vivo Functions and In Vitro Applications. Nutrients. 2023; 15: 2734.

- Serin HM, Arslan EA. Neurological symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency: analysis of pediatric patients. Acta Clin Croat. 2019; 58: 295-302.

- Lauer AA, Grimm HS, Apel B, Golobrodska N, Kruse L, Ratanski E, et al. Mechanistic Link between Vitamin B12 and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules. 2022; 12: 129.

- Douaud G, Refsum H, de Jager CA, Jacoby R, Nichols TE, Smith SM,et al. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease-related gray matter atrophy by B-vitamin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110: 9523-9528.

- Clarke R, Birks J, Nexo E, Ueland PM, Schneede J, Scott J, et al. Low vitamin B-12 status and risk of cognitive decline in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007; 86: 1384-1391.

- Mohan A, Kumar R, Kumar V, Yadav M. Homocysteine, Vitamin B12 and Folate Level: Possible Risk Factors in the Progression of Chronic Heart and Kidney Disorders. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2023; 19: e090223213539.

- Ueno A, Hamano T, Nagata M, Yamaguchi T, Endo Y, Enomoto S, et al. Association of vitamin B12 deficiency in a dementia cohort with hippocampal atrophy on MRI. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2025; 12: 100265.

- Clarke R, Bennett D, Parish S, Lewington S, Skeaff M, Eussen SJ, et al. B-Vitamin Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects of homocysteine lowering with B vitamins on cognitive aging: meta-analysis of 11 trials with cognitive data on 22,000 individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014; 100: 657-666.

- Rabensteiner J, Hofer E, Fauler G, Fritz-Petrin E, Benke T, Dal-Bianco P, et al. The impact of folate and vitamin B12 status on cognitive function and brain atrophy in healthy elderly and demented Austrians, a retrospective cohort study. Aging (Albany NY). 2020; 12: 15478-15491.

- Lee CY, Chan L, Hu CJ, Hong CT, Chen JH. Role of vitamin B12 and folic acid in treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Aging (Albany NY). 2024; 16: 7856-7869.

- Alzahrani H. Assessment of Vitamin B12 Efficacy on Cognitive Memory Function and Depressive Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2024; 16: e73350.

- Mathew AR, Di Matteo G, La Rosa P, Barbati SA, Mannina L, Moreno S, et al. Vitamin B12 Deficiency and the Nervous System: Beyond Metabolic Decompensation-Comparing Biological Models and Gaining New Insights into Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25: 590.

- Douaud G, Refsum H, de Jager CA, Jacoby R, Nichols TE, Smith SM, et al. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease-related gray matter atrophy by B-vitamin treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013; 110: 9523-9528.

- Brito A, Grapov D, Fahrmann J, Harvey D, Green R, Miller JW, et al. The Human Serum Metabolome of Vitamin B-12 Deficiency and Repletion, and Associations with Neurological Function in Elderly Adults. J Nutr. 2017; 147: 1839-1849.

- Moretti R, Caruso P. The Controversial Role of Homocysteine inNeurology: From Labs to Clinical Practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20: 231.

- Jatoi S, Hafeez A, Riaz SU, Ali A, Ghauri MI, Zehra M. Low Vitamin B12 Levels: An Underestimated Cause Of Minimal Cognitive Impairment And Dementia. Cureus. 2020; 12: e6976.

- Smith AD, Refsum H. Homocysteine, B Vitamins, and Cognitive Impairment. Annu Rev Nutr. 2016; 36: 211-239.

- Smith AD, Refsum H, Bottiglieri T, Fenech M, Hooshmand B, McCaddon A, et al. Homocysteine and Dementia: An International Consensus Statement. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018; 62: 561-570.

- Marino FR, Rogers G, Miller JW, Selhub J, Mez J, Crane PK, et al. Higher vitamin B12 from mid- to late life is related to slower rates of cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement. 2025; 21: e70864.

- Oulhaj A, Jernerén F, Refsum H, Smith AD, de Jager CA. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Status Enhances the Prevention of Cognitive Decline by B Vitamins in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016; 50: 547-557.

- McCaddon A, Miller JW. Homocysteine-a retrospective andprospective appraisal. Front Nutr. 2023; 10: 1179807.

- Dali-Youcef N, Andrès E. An update on cobalamin deficiency in adults. QJM. 2009; 102: 17-28.

- Durga J, van Boxtel MP, Schouten EG, Kok FJ, Jolles J, Katan MB, et al.Effect of 3-year folic acid supplementation on cognitive function inolder adults in the FACIT trial: a randomised, double blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2007; 369: 208-216.

- Obeid R, Andrès E, ?eška R, Hooshmand B, Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Prada GI, et al, The Vitamin B Consensus Panelists Group. Diagnosis, Treatment and Long-Term Management of Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Adults: A Delphi Expert Consensus. J Clin Med. 2024; 13: 2176.