Short-Term Open-Field Testing Reveals Sex- and Age Dependent Behavioral Patterns in Mice

- 1. Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Colorado State University, USA

Abstract

Standardization in behavioral testing is essential for reproducibility and translational relevance in preclinical research. Overhead video monitoring systems, commonly used to assess spontaneous behavior in rodents, can vary significantly in test duration and interpretation, which limits cross-study comparisons. This study aimed to define optimal short-term overhead video monitoring durations and provide behavioral references across age and sex in naïve C57BL/6 mice. We conducted open-field assessments with juvenile and adult mice of both sexes, analyzing key behavioral parameters relating to mobility, exploration, and anxiety/vigilance. Our findings demonstrate that behavior varies significantly with age and sex. Juvenile mice exhibited exploratory behaviors and resting behaviors, while adults had increased anxiety-like behaviors; female mice showed more complex and variable behavioral patterns compared to males. The 2.5-minute sessions revealed stable and statistically significant differences in male behavior, suggesting that short-term monitoring can be both efficient and informative when applied appropriately. However, longer sessions (≥10 minutes) were required to fully capture behavioral variability in females. This study provides empirical guidance for selecting test durations and interpreting behavioral data in overhead video monitoring. The results support the implementation of sex- and age-appropriate protocols to improve the consistency and interpretability of behavioral outcomes. These insights contribute to the broader goal of standardizing preclinical mobility and pain assessments, thereby enhancing the rigor and utility of rodent models in osteoarthritis and related fields.

Keywords

• Behavior/Mobility

• Sex Differences

• Age Differences

• Overhead Video Monitoring

• Open-Field Testing

Citation

Kloser H, Henao-Tamayo M, Santangelo KS (2025) Short-Term Open-Field Testing Reveals Sex- and Age-Dependent Behavioral Patterns in Mice. J Aging Age Relat Dis 4(1): 1007.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past two decades, there has been a substantial increase in the number of studies utilizing pain, behavior, and mobility outcomes in animal models. This increase likely reflects several converging trends. First, there is a growing demand for a deeper understanding of pain mechanisms and more effective treatment strategies for chronic pain conditions in humans [1]. Second, major funding bodies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have actively incentivized the incorporation of pain related endpoints into preclinical research, recognizing the urgent public health need to address pain prevention, treatment, and disparities in care [2,3]. Animal models continue to play a central role in meeting these research needs [1-5]. Third, following the demand for understanding, advances in computing power, artificial intelligence, and video tracking technology have dramatically expanded our ability to quantify animal behavior. These tools have made it easier and more cost-effective for researchers to collect multiparameter behavioral data from living animals [4-8]. Early studies of spontaneous behavior in rodents often relied on direct observation, where researchers manually scored behaviors using pain scales or ethograms [1-4]. Over time, these techniques evolved into video assisted scoring methods, which enabled more consistent and less time-intensive data collection [4-9]. Given that rodents are prey animals and tend to mask signs of pain, researchers have sought to develop more sensitive direct and indirect behavioral assays to detect pain [4]. These include evaluating nest complexity, observing burrowing behavior, and using grimace scales to measure discomfort and the effectiveness of pain-relieving therapies [10-12]. Open-field testing has benefited especially from recent technological advances. Automated overhead video tracking software now enables researchers to monitor and analyze detailed patterns of animal mobility, activity, and presumed pain-related behaviors [7-14]. However, as these tools have become more widely adopted, a new challenge has emerged: standardizing how these data are collected, analyzed, and reported [5]. Despite the availability of technologies that output accurate and usable data, the variability in test durations, parameter selection, and analytical approaches among studies has created inconsistencies in interpretation and reproducibility [1 15]. For example, studies using overhead video monitoring have reported testing durations ranging from overnight (~15 hours) to short 2–3-minute recordings [13-16]. Despite many of these systems producing comparable raw data, the lack of uniform analytical frameworks and baseline comparison strategies may limit the ability to compare findings across studies, thereby hindering the field’s overall progress. To address these issues, it is crucial to standardize behavioral assays in pain research-not only to enhance reproducibility, but also to ensure that researchers select test durations and parameters that are suitable for their specific scientific questions [1-17]. This is especially important given the time-intensive nature of behavioral testing. By establishing evidence-based guidelines, researchers can optimize their study designs, reduce unnecessary testing, and extend the value of their research funding. In this study, we analyzed the behavior and mobility patterns of naïve male and female C57BL/6 mice at two developmental stages: juveniles (4 weeks old) and adults (34 weeks old), using an overhead video monitoring system. Our objective was to determine the optimal test duration and behavioral parameters that allow researchers to detect meaningful sex- and age-based differences in spontaneous behavior. By doing so, we aim to provide practical guidelines for selecting appropriate test durations and analytical strategies based on the research context, ultimately contributing to greater coherence and efficiency in the expanding field of pain and behavioral analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. All procedures regarding animal usage were approved by Colorado State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC #1277 & 4829), and were performed following the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Twenty-eight naïve C57/ BL6J mice (14 male, 14 female) (Charles River), arrived at 3-4 weeks of age; acclimation started at 4 weeks old. All mice underwent two acclimation days in the ANY mazeTM cage apparatus to ensure familiarity and comfort before data collection [8-19]. Mice were co-housed in solid-bottom cages in groups of four, randomly assigned by animal resource staff by sex upon arrival, and allowed ad libitum water and standard rodent chow. Animals were kept at 20-25ºC with a 12-12 hr. light-dark cycle and 30 70% humidity. Body weight was monitored weekly, and all animals were examined by a veterinarian daily. ANY-mazeTM Overhead Video Monitoring. Animal behavior and mobility were assessed using the ANY maze™ software (Wood Dale, IL) with an overhead open field video monitoring system. Mice were acclimated to the testing apparatus, a catch cage equipped with a rectangular security hut, for two 10-minute sessions on separate days prior to baseline data collection. Behavioral testing was conducted in 10-minute sessions at designated time points (4 and 34 weeks of age). All data shown in this manuscript were taken as segments of the 10-minute tests. Specifically, the first 2.5 minutes and 5 minutes were taken from the 10-minute test; the 10-minute segment was the entire tested time. To maintain familiarity with the setup between these two recorded testing sessions at 4 and 34 weeks of age, mice received additional brief exposures: either recorded 5-minute sessions (data not shown) or unrecorded 2-minute sessions. Acclamation, maintenance, and data collection were performed at the same time of day (within a two-hour window) for each cage and involved the same handlers [8-19]. Data Analysis. ANY-mazeTM results were generated via the ANY-mazeTM tracking software outputs and analyzed in R Studio (version 2023.06.0+421) via R (version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14)). Briefly, CSV files were imported into R from ANY-mazeTM, and a pipeline (the same code applied to all inputs) was generated to compute statistics and display graphs. Analysis groups were by age, sex, or both, with individual animals shown. Normality was assessed to determine the appropriate statistical tests. Paired parametric t-tests or Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests were run on comparisons between the same animals from one time point to another. Unpaired parametric t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests were run when comparing different animals (i.e., M vs. F). Test type is denoted on the figures. Statistical significance was considered p<0.05; all p-values are listed in the figures. Single asterisks are also placed on graphs to denote any statistical significance. The animals were part of a dual-use study, and as such, sample sizes were determined before the experiments based on statistical relevance to the primary study. To ensure statistical relevance from the sample sizes for this secondary study, post hoc sample calculations were performed using mean speed between 4- and 34-week-old animals, and a power analysis was conducted via G*power 3.1, yielding a power of 0.964.

RESULTS

Analysis of test duration when considering age (without sex as a variable). To determine generalized mouse behavior with aging for studies that may consider both sexes, we combined the results of both female and male animals. In this section, we examined behavioral changes with 2.5, 5, and 10 minutes of monitoring as animals aged from 4 to 34 weeks old (Figure 1-3). Overall, the 2.5-minute tests were able to pick up the same statistical differences observed in the 5 and 10-minute tests, as well as an additional behavioral difference between the young and older mice.

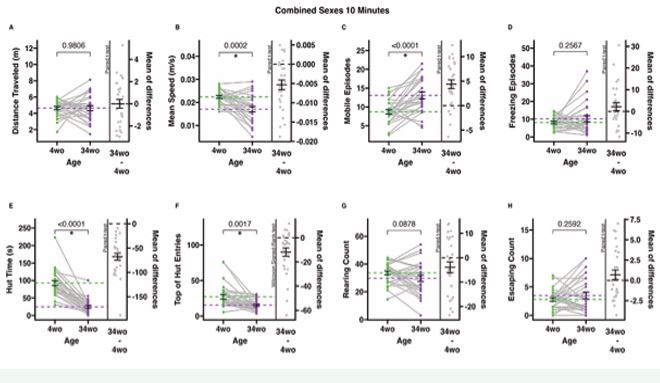

Figure 1 10-minute-long ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of male and female mice at 4 and 34 weeks old. Dots represent individual animals (n=28); grey lines connect individual animals from the first to the second time point; dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). The mean of difference is calculated on the right-hand side of the graphs, with a dotted line at 0, a solid line at the mean, and SE error bars. A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes count the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries count the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

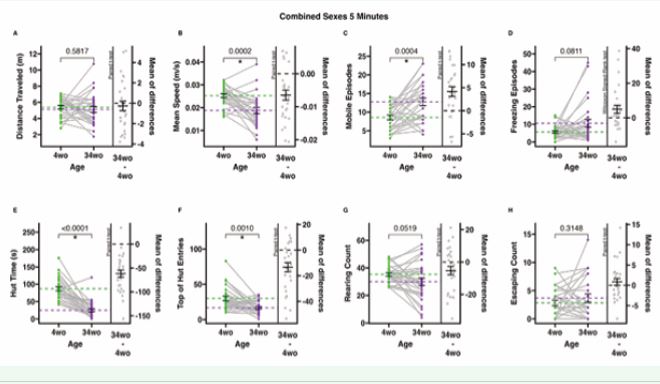

significantly different included distance travelled, freezing episodes, rearing count, and escaping count (Figure 1A, D, G-H). Five-minute-long overhead video monitoring tests demonstrated the same significant behavioral/mobility differences and similarities between 4-week-old and 34-week-old animals as the 10-minute tests (Figure 2B C, E-F). Outcomes that were not significantly different included distance travelled, freezing episodes, rearing count, and escaping count (Figure 2A, D, G-H)

Figure 2 5-minute-long ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of male and female mice at 4 and 34 weeks old. Dots represent individual animals (n=28); grey lines connect individual animals from the first to the second time point; dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). The mean of difference is calculated on the right-hand side of the graphs, with a dotted line at 0, a solid line at the mean, and SE error bars. A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes, counts the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries count the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

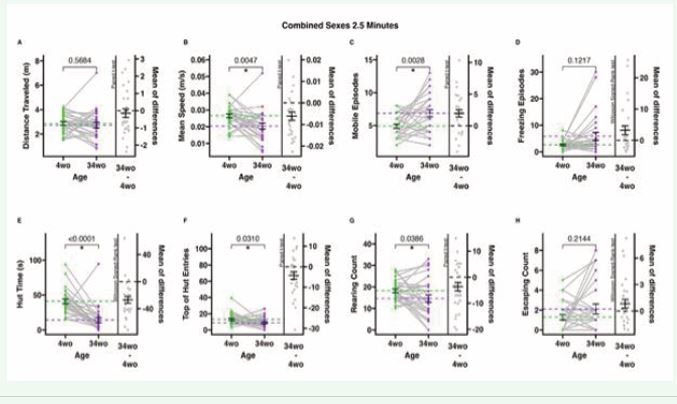

Figure 3 2.5-minute-long ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of male and female mice at 4 and 34 weeks old. Dots represent individual animals (n=28); grey lines connect individual animals from the first to the second time point; dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). The mean of difference is calculated on the right-hand side of the graphs, with a dotted line at 0, a solid line at the mean, and SE error bars. A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes count the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries count the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

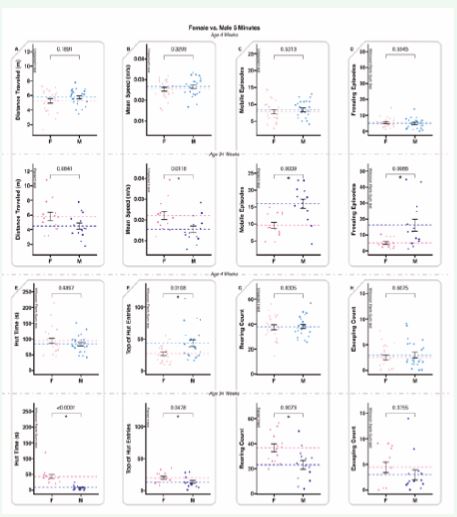

Two-and-a-half-minute-long overhead video monitoring tests also demonstrated the same significant differences between 4-week-old and 34-week-old animals as the 10-minute and 5-minute tests (Figure 3B-C, E-F). In addition, the 2.5-minute tests detected significant differences in rearing behavior, whereas the 5 and 10-minute tests did not (Figure 3G). Behavioral measures that remained consistent as they aged included distance travelled, freezing episodes, and escaping count (Figure 3A, D, H (Figure 3G).).Analysis of sex differences between 4-week-old and 34-week-old mice. Female and male mice were separated by sex and age to compare differences between each sex at each age. In this section, we examined sex differences between juvenile mice (4 weeks) and between sexually mature mice (34 weeks). Interestingly, juvenile mice exhibited more similar behaviors between sexes than sexually mature mice. We examined behavioral differences in 2.5, 5, and 10-minute tests (Figure 4-6).

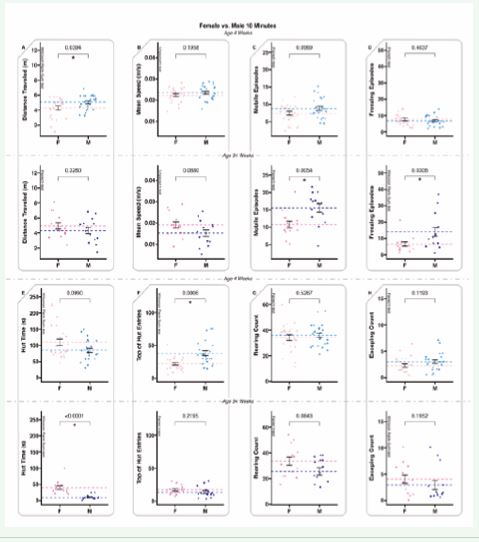

Ten-minute-long testing revealed that most behaviors were consistent between the two sexes at both ages. Interestingly, the behavior differences picked up between juvenile males and females were different than those picked up between the sexually mature animals. Specifically, distance travelled and top of hut entries (Figure 4A, F), differed for the juvenile animals, with the males exhibiting more of both behaviors. The sexually mature animals exhibited differences between the sexes for mobile and freezing episodes (Figure 4C-D), (with males exhibiting more of both behaviors) and hut time (Figure 4E) (with females exhibiting more hut time). Juvenile animals had two statistical differences and sexually mature animals had three. Behaviors that remained consistent between the 4-week-old animals were mean speed, mobile episodes, freezing episodes, hut time, rearing count, and escaping count (Figure 4B-E, G-H). Behaviors that did not change between the 34-week-old animals included distance traveled, mean speed, rearing count, and escaping count (Figure 4A-B, F-H).

Figure 4 10-minute-long ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of 4-week-old and 34-week-old animals examining differences between sexes. 4-week-old animals are displayed before 34-week-old animals; dots represent individual animals (n=28); dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes count the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries counts the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

Five-minute tests exhibited fewer differences between sexes for the juvenile animals than the 10-minute tests. The only difference was top-of-hut entries (Figure 5E) (where males exhibited more of this behavior). In contrast, the sexually mature animals had significantly more behavioral differences between sexes in the 5-minute tests than in the 10-minute tests (Figure 5B-G). Males had increased mobile and freezing episodes over females (Figure 5C-D), where the females had increased mean speed, hut time, top of hut entries, and rearing than the males (Figure 5B, E-G). Juvenile animals had one statistical difference, and sexually mature animals had six. Juvenile animals exhibited similar behaviors for distance traveled, mean speed, mobile episodes, freezing episodes, hut time, rearing count, and escaping count (Figure 5A-E, G-H). In contrast, the adult animals only had similar behaviors for distance traveled and escaping count (Figure 5A, H).

Figure 5 5-minute-long ANY-mazeTM ?overhead video monitoring of 4-week-old and 34-week-old animals examining differences between sexes. 4-week-old animals are displayed before 34-week-old animals; dots represent individual animals (n=28); dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes count the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries count the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

Two-and-a-half-minute tests exhibited no significant differences between the sexes for juvenile animals; as such, all measures were similar for this age for this time segment (Figure 6). In contrast, the sexually mature animals exhibited six significant differences (the same six as observed in the 5-minute tests, with the same male female trends) (Figure 6B-G), with distance traveled and escaping count remaining similar for adult males and females (Figure 6A, H).

Figure 6 2.5-minute-long ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of 4-week-old and 34-week-old animals examining differences between sexes. 4-week-old animals are displayed before 34-week-old animals; dots represent individual animals (n=28); dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes counts the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries counts the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

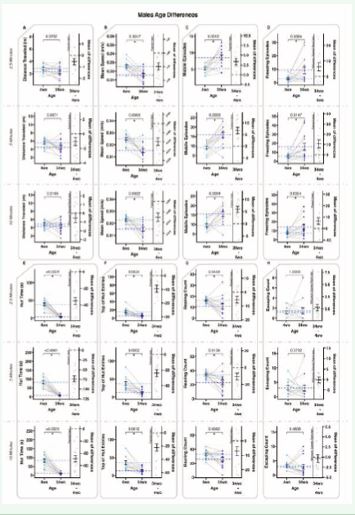

the changes in animal behavior within each sex as they mature, we separated male and female animals and examined the differences between test durations for each sex (Figure 7-8). Overall, females did not exhibit many behavioral changes from juvenile to sexually mature, and when present, longer tests were required to detect such (Figure 7). Conversely, juvenile and sexually mature males exhibited different behaviors in nearly all measures, and the results were consistent across all times tested (Figure 8). Female mice exhibited fairly consistent behavior as they matured. Our data demonstrated that 2.5-minute tests were not long enough to detect any behavioral differences between juvenile and sexually mature animals; as such, all measures were statistically similar (Figure 7). 5-minute tests only differentiated the behavior between the ages for a single parameter, hut time, where juveniles spent more time in the security hut than sexually mature animals (Figure 7E); all other measures were statistically similar (Figure 7A-D, F-H). Hut time was consistently different between the two ages in 10-minute tests (Figure 7E). In addition to hut time, three other measures revealed behavioral differences between the age groups in 10-minute tests. Mobile episodes and escaping count were both increased in the sexually mature animals (Figure 7C & H), whereas mean speed was decreased (Figure 7B). In the 10-minute tests, the distance traveled, freezing episodes, top of hut entries, and rearing count were similar for both age groups (Figure 7A, D, F-G).

Figure 7 ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of the differences between 4 and 34-week-old female animals in 2.5, 5, & 10-minute-long tests. Dots represent individual animals (n=14); grey lines connect individual animals from the first to the second time point; dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). The mean of difference is calculated on the right-hand side of the graphs, with a dotted line at 0, a solid line at the mean, and SE error bars. A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes count the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries count the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

Juvenile and adult males exhibited behavioral differences in most tested measures, regardless of time. Adult males exhibited increased mobile episodes and freezing episodes compared to juveniles in 2.5-, 5-, and 10-minute tests (Figure 8C-D). In contrast, the juveniles had higher mean speeds, hut time, top-of-hut entries, and rearing counts than adults in 2.5-, 5-, and 10-minute tests (Figure 8B, E-G). Distance traveled and escaping count were the only behaviors to remain similar between the 4 and 34-week-old animals (Figure 8A, H).

Figure 8 ANY-mazeTM overhead video monitoring of the differences between 4 and 34-week-old male animals in 2.5, 5, & 10-minute-long tests. Dots represent individual animals (n=14); grey lines connect individual animals from the first to the second time point; dotted lines represent means, and error bars represent standard error (SE). The mean of difference is calculated on the right-hand side of the graphs, with a dotted line at 0, a solid line at the mean, and SE error bars. A. The total distance (meters) the animals traveled during the test. B. The mean speed (meters/second) of the animals only during mobile time (adjusted mean speed). C. Mobile episodes count the number of times the animals start moving from an immobile or freezing episode. D. Freezing episodes count the number of times the animals suppress all movement. E. Hut time (seconds) measures how long animals spend in their residential security hut (the security hut blocks the camera view, and all hut time is excluded from all other measures). F. Top of hut entries count the number of times animals climb on top of the security hut. G. Rearing counts the number of times the animals rear. H. Escaping counts the number of times the animals attempted to climb out of the testing cage (during this behavior, animals were gently alerted with a noise to provoke a return to the cage).

DISCUSSION

Because a primary goal of mouse-based behavioral and pain research is to inform human studies, it is essential to consider how mouse behavior trends compare to those of humans [1-23]. While no animal model can replicate every aspect of human disease, mouse behavior reported in juvenile and adult animals may mirror certain aspects of human behavior, such as increased mobility followed by increased resting in juveniles [5-25]. Indeed, the results from this study also support that juvenile mice, regardless of sex, exhibit similar behavioral profiles and thereby parallel human developmental patterns [17-24]. Further, findings from this study and others demonstrate that behavioral differences between the sexes typically emerge or intensify during adolescence and persist into adulthood, which is also a scenario seen in humans [24-27]. Juvenile versus adult behavior. When comparing juvenile and adult animals, we and others observed behavioral trends that parallel those seen in human development. [17-26] For instance, the study by Macri et al. compared mice at juvenile (35 days, ~5 weeks), adolescent (48 days, ~ 6 weeks), and adult (61 days, ~ 8 weeks) stages. When looking at behavioral categories between different types of behavior and mobility assays, our study generally supported their findings for both younger and older animals. In their experiment, they utilized a plus-maze system and reported that both juveniles and adults demonstrated more anxiety like behaviors, avoiding the open arms of the maze [24]. Additionally, their behavioral analysis of adult animals also revealed sex-specific differences, with adult males entering closed arms more frequently than females, and a non-significant trend toward more rearing in males. Interestingly, this is in contrast to our findings, where 34-week-old females reared significantly more than males in the open field test [24]. In the context of behavioral differences between the ages, juvenile mice show more dynamic exploratory behaviors compared to adults [17-33]. While there were no differences in total distance traveled between age groups, juveniles in our study exhibited higher mean speeds, more rearing events, and more frequent entries to the top of the hut-indicators of increased exploratory drive when in motion [30-33]. Notably, juveniles also spent more time resting in the hut, suggesting that their bursts of activity may be more energy-intensive, requiring more frequent recovery periods. In contrast, adult mice exhibited behaviors suggestive of heightened vigilance or anxiety, including increased numbers of mobile and freezing episodes [31,32]. These findings mirror previous reports that adult rodents often display greater behavioral variability and anxiety-related traits than juveniles [17]. Sex-dependent behavior. When analyzing age-related behavioral differences by sex, we found that male mice primarily drove the observed age-related changes. Female mice showed minimal differences between age groups, and short 2.5-minute tests failed to detect any significant age related changes. Indeed, statistical differences in female behavior only emerged during longer test durations, suggesting two possibilities: either female mice maintain highly consistent behaviors as they age, making them applicable models for detecting treatment effects, or longer tests (10 minutes or more) are required to uncover subtle age-related differences. In contrast, male mice exhibited apparent behavioral differences between the juvenile and adult stages, regardless of the test duration. Only two behaviors distance traveled and escaping episodes—remained stable across ages in males, making these parameters reliable for identifying meaningful behavioral changes over time. As discussed more below, because these behaviors are not influenced by age, they may serve as stable reference points in longitudinal or comparative studies. The study by Schuster et al., reported that sex differences in behavior become more pronounced after sexual maturity; thus, juvenile animals are more similar to one another than to adults [26]. In our study, juvenile male and female mice exhibited largely similar behaviors across most measures. During the 2.5-minute tests, behavior was highly comparable between sexes. Notable differences emerged only with extended test durations and in a few measures. Specifically, in the 10-minute tests, 4-week-old males displayed increased exploratory behavior, including increased distance traveled and more frequent climbing on the hut, compared to females. Interestingly, this trend was not present by week 34, when females climbed on the hut more frequently than males during the 5-minute tests [26]. Notably, human children exhibit similar behavioral patterns across sex, such as emotional expressions and motor milestones, between infancy and preschool age [28,29]; however, by preschool, behaviors start to diverge by sex [28]. Through adolescence and into adulthood, males engage in higher risk-taking and sensation-seeking, while females tend to show more stable, socially oriented behaviors throughout life [24-28]. While the emotional and cognitive dimensions of human development cannot be directly modeled in mice, sex- and age-related shifts in rodent behavior, particularly in commonly used strains such as C57BL/6J, mirror some of these developmental trajectories [17-26]. For example, while juvenile male and female mice often display similar patterns of activity, divergence becomes more apparent with age, particularly in behaviors associated with exploration or anxiety-like responses [17-30]. One study using an elevated plus maze found that adolescent male mice exhibited more risk taking behavior than females and both younger and older age groups [24]. These types of assays may not capture the full complexity of human behavior but do provide a translationally relevant framework for examining how age and sex shape behavioral responses in preclinical models [17-26]. In our study, we also observed several behavioral differences between the sexes as adults that were not evident in juveniles. For example, the female animals exhibited increased hut time, top of hut entries, rearing, and mean speed, behaviors associated with exploring and recovering. Males, on the other hand, had increased mobile episodes and freezing episodes compared to the females, behaviors typically associated with more anxiety, as supported by the results of Macri et al. [24-32]. Additionally, adult male animals had increased distance traveled compared to females in the 10-minute tests, indicating that, due to the increased hut time observed in females, longer tests may reveal differences in mobility between the sexes. Test parameter considerations. When designing studies that include both sexes, separating data analysis by sex may improve sensitivity and interpretability, especially in studies involving adult or aging animals. Additionally, for experiments that span developmental stages or include multiple time points, focusing on stable parameters, such as distance traveled, can help ensure that observed differences reflect treatment effects rather than age-related behavioral variability. In our study, distance traveled was the most consistent behavior across groups, with only one statistically significant difference observed (between juvenile males and females at the 10-minute time point). No other distance traveled comparisons reached significance. For studies involving male mice, even short 2.5-minute tests appear sufficient to detect behavioral differences. For female mice, while behavior may be more stable and potentially more reliable for detecting treatment effects, longer test durations may be required to reveal significant changes.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, our findings support the growing body of evidence that age and sex have a profound influence on spontaneous behavior in laboratory mice [17-24]. Moreover, they highlight the importance of selecting appropriate time points and behavioral parameters when designing experiments, particularly for studies focused on pain, anxiety, or exploratory behavior [1-33]. As the field continues to expand with new technologies and more refined behavioral assays, there is a pressing need for standardized methods to improve the comparability and translatability of results [1-15]. Our study contributes to this effort by identifying behavioral readouts that are sensitive to both age and sex, thereby providing a foundation for future research design and interpretation.Recommendations. Based on the behavioral consistency and variability observed in this study, several key considerations can help guide the design of future open-field behavioral experiments, particularly those focused on osteoarthritis and mobility-related outcomes. First, proper animal acclimation is critical to reducing variability and enhancing reproducibility. Acclimation sessions should occur in the same room, at the same time of day, and with the same handlers as the testing sessions to minimize confounding variables. Each animal should receive at least two training sessions, each equal in duration to the testing period, to ensure familiarity with the apparatus. To further strengthen the study design, baseline behavioral measurements should be collected prior to experimental manipulation. Whenever possible, at least two baseline measurements should be taken and averaged for each animal to account for day-to-day variability and improve statistical power for within subject comparisons. Test duration should be tailored to the sex of the animals. For male mice of any age, this study supports the use of short 2.5-minute sessions, as they were sufficient to detect group-level behavioral differences. For female mice, however, we recommend using sessions of 10 minutes or longer, as the behavioral differences were less detectable in shorter time frames. Additional studies are needed to determine if shorter durations are appropriate for female cohorts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the undergraduate researchers Daryl Conner, Hogarth Dorst, and Sage Phuepwint for their help in collecting the behavioral and mobility data. We also thank Ann Hess for her helpful advice on statistical analysis. The animals used in this study were part of a dual-use study and funded by the primary study, Mechanisms of Protection Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Center (IMPAc-TB), “A Cross-Species Mechanistic Interrogation of Mycobacterial and Vaccine-Induced Immunity” (NIH Contract No. 75N93021C00029). H. Kloser was supported by NIH, IDRRN OVPR T32 1678667. We also gratefully acknowledge the Rosenbach and Clanton families, whose donations helped support this research.

REFERENCES

- Gregory NS, Harris AL, Robinson CR, Dougherty PM, Fuchs PN. An overview of animal models of pain: disease models and outcome measures. J Pain. 2013; 14: 1255-1269.

- Koroshetz WJ, Hodes R, Criswell LA, D’Souza R, Rodgers GP, BakerR. Letter from the Director New Opportunities for Advancing Pain Science. 2022.

- NIH HEAL Initiative. NIH. 2025.

- Turner PV, Pang DS, Lofgren JL. A Review of Pain Assessment Methods in Laboratory Rodents. Comp Med. 2019; 69: 451-467.

- Malfait AM, Little CB, McDougall JJ. A commentary on modelling osteoarthritis pain in small animals. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013; 21: 1316-1326.

- Piel MJ, Kroin JS, van Wijnen AJ, Kc R, Im HJ. Pain assessment in animal models of osteoarthritis. Gene. 2014; 537: 184-188.

- Inglis JJ, McNamee KE, Chia SL, Essex D, Feldmann M, Williams RO, et al. Regulation of pain sensitivity in experimental osteoarthritis by the endogenous peripheral opioid system. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 58: 3110-3119.

- Pezzanite LM, Timkovich AE, Sikes KJ, Chow L, Hendrickson DA, Becker JR, et al. Erythrocyte removal from bone marrow aspirate concentrate improves efficacy as intra-articular cellular therapy in a rodent osteoarthritis model. Ann Transl Med. 2023;11: 311.

- Salvarrey-Strati A, Watson L, Blanchet T, Lu N, Glasson SS. The influence of enrichment devices on development of osteoarthritis in a surgically induced murine model. ILAR J. 2008; 49: 23-30.

- Rapp AE, Wolter A, Muschter D, Grässel S, Lang A. Impact of sensory neuropeptide deficiency on behavioral patterns and gait in a murine surgical osteoarthritis model. J Orthopaedic Res. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2024.

- improvement: C57BL/6J mice given more naturalistic nesting materials build better nests. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2008; 47: 25- 31.

- Ai M, Hotham WE, Pattison LA, Ma Q, Henson FMD, Smith ESJ. Role of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Reducing Sensory Neuron Hyperexcitability and Pain Behaviors in Murine Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023; 75: 352-363.

- Miller RE, Tran PB, Das R, Ghoreishi-Haack N, Ren D, Miller RJ, et al. CCR2 chemokine receptor signalling mediates pain in experimental osteoarthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012; 109: 20602-20607.

- Tang YZ, Chen W, Xu BY, He G, Fan XC, Tang KL. 4-Octyl itaconate inhibits synovitis in the mouse model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and alleviates pain. Chinese J Traumatol. 2024;

- Malfait AM, Ritchie J, Gil AS, Austin JS, Hartke J, Qin W, et al. ADAMTS-5 deficient mice do not develop mechanical allodynia associated with osteoarthritis following medial meniscal destabilization. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010; 18: 572-580.

- Li W, Lv Z, Wang P, Xie Y, Sun W, Guo H, et al. Near Infrared Responsive Gold Nanorods Attenuate Osteoarthritis Progression by Targeting TRPV1. Advanced Science. John Wiley and Sons Inc; 2024; 11.

- Shoji H, Takao K, Hattori S, Miyakawa T. Age-related changes in behavior in C57BL/6J mice from young adulthood to middle age. Mol Brain. 2016; 9: 11.

- Timkovich AE, Holling GA, Afzali MF, Kisiday J, Santangelo KS. TLR4 antagonism provides short-term but not long-term clinical benefit in a full-depth cartilage defect mouse model. Connect Tissue Res. 2024; 65: 26-40.

- Timkovich AE, Sikes KJ, Andrie KM, Afzali MF, Sanford J, Fernandez K, et al. Full and Partial Mid-substance ACL Rupture Using Mechanical Tibial Displacement in Male and Female Mice. Ann Biomed Eng. 2023; 51: 579-593.

- Wu CL, Jain D, McNeill JN, Little D, Anderson JA, Huebner JL, et al. Dietary fatty acid content regulates wound repair and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis following joint injury. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015; 74: 2076-2083.

- Alves CJ, Couto M, Sousa DM, Magalhães A, Neto E, Leitão L, et al. Nociceptive mechanisms driving pain in a post-traumatic osteoarthritis mouse model. Sci Rep. 2020; 10: 15271.

- Fahlström A, Yu Q, Ulfhake B. Behavioral changes in aging femaleC57BL/6 mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2011; 32: 1868-1880.

- An XL, Zou JX, Wu RY, Yang Y, Tai FD, Zeng SY, et al. Strain and sex differences in anxiety-like and social behaviors in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Exp Anim. 2011; 60:111-123.

- Macrì S, Adriani W, Chiarotti F, Laviola G. Risk taking during exploration of a plus-maze is greater in adolescent than in juvenile or adult mice. Anim Behav. Academic Press; 2002; 64: 541-546.

- Johnson C, Wilbrecht L. Juvenile mice show greater flexibility in multiple choice reversal learning than adults. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011; 1: 540-551

- Schuster AC, Carl T, Foerster K. Repeatability and consistency of individual behaviour in juvenile and adult eurasian harvest mice. Science of Nature. Springer Verlag; 2017; 104.

- Hwang HS, Park IY, Hong JI, Kim JR, Kim HA. Comparison of joint degeneration and pain in male and female mice in DMM model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021; 29: 728-738.

- Chaplin TM. Gender and Emotion Expression: A Developmental Contextual Perspective. Emot Rev. 2015; 7: 14-21.

- Capute AJ, Shapiro BK, Palmer FB, Ross A, Wachtel RC. Normal gross motor development: the influences of race, sex and socio-economic status. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1985; 27: 635-643.

- Gould TD, Dao DT, Kovacsics CE. The Open Field Test. Mood and Anxiety Related Phenotypes in Mice. 2009; 1-20.

- Sartori SB, Landgraf R, Singewald N. The clinical implications of mouse models of enhanced anxiety. Future Neurol. 2011; 6: 531-571.

- Lezak KR, Missig G, Carlezon WA Jr. Behavioral methods to study anxiety in rodents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017; 19: 181-191.

- Sturman O, Germain PL, Bohacek J. Exploratory rearing: a context- and stress-sensitive behavior recorded in the open-field test. Stress. 2018; 21: 443-452.

- Ma HL, Blanchet TJ, Peluso D, Hopkins B, Morris EA, Glasson SS. Osteoarthritis severity is sex dependent in a surgical mouse model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007; 15: 695-700.

- Li J, Wang Y, Chen D, Liu-Bryan R. Oral administration of berberine limits post-traumatic osteoarthritis development and associated pain via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in mice. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2022; 30: 160-171.

- Wan Y, Shen K, Yu H, Fan W. Baicalein limits osteoarthritis development by inhibiting chondrocyte ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023; 196: 108-120.

- Lv Z, Wang P, Li W, Xie Y, Sun W, Jin X, et al. Bifunctional TRPV1 Targeted Magnetothermal Switch to Attenuate Osteoarthritis Progression. Research (Wash D C). 2024; 7: 0316.

- Qian YX, Rao SS, Tan YJ, Wang Z, Yin H, Wan TF, et al. Intermittent Fasting Targets Osteocyte Neuropeptide Y to Relieve Osteoarthritis. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024; 11: e2400196.