Ictal Onset Alpha on Scalp EEG in a Child with Lesional Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: A Case Report

- 1. National Neuroscience Institute, King Fahad Medical City, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

In a recording of normal scalp EEG, alpha activity is the main posterior dominant background rhythm in adults and children older than 3 years. Abnormalities in the alpha rhythm include slowing, changes in amplitude, or absence of the posterior dominant background rhythm under varying conditions. In epilepsy, alpha abnormalities are recorded interictally and preictally. During intracranial EEG, bands of faster frequency are commonly recorded; these have been well characterized with or without an association with the epileptogenic zone. Alpha activity is not widely recognized as an ictal pattern at seizure onset on scalp EEG in patients with epilepsy. At onset, mesial temporal onset seizures are strongly correlated with rhythmic theta activity, whereas neocortical (lateral) onset seizures have been associated with delta activity.

Keywords

• EEG

• Ictal Alpha

• Temporal Seizure

• Epilepsy

Citation

Fallatah A, Alwadei AH (2025) Ictal Onset Alpha on Scalp EEG in a Child with Lesional Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: A Case Report. J Autism Epilepsy 6(1): 1020.

INTRODUCTION

EEG is the standard tool used to establish localization in presurgical evaluations that aim to delineate the zone of seizure onset. This is crucial for predicting the outcome of epilepsy surgery. Ictal EEG patterns in temporal lobe epilepsy have been described as rhythmic theta activity in seizures originating from the mesial temporal lobe, and rhythmic or arrhythmic delta activity in seizures originating from the neocortical temporal lobe, as widely encountered [1-3].

Using invasive EEG, alpha can be observed at the onset of ictal events, although faster frequencies that include beta, gamma, and high frequency oscillations are more frequently reported and have proven to be reproducible in several studies [4-6].

Interictal or preictal changes in the background alpha rhythm are abnormalities that have been described in focal epilepsy and other conditions [7-10]. However, alpha rhythm is not typically correlated with ictal EEG onset of temporal lobe epilepsy on standard scalp EEG recordings [11-13]. Herein, we present a unique case of lesional temporal lobe epilepsy with an ictal onset alpha rhythm that was recorded during video EEG monitoring of the scalp for presurgical evaluation.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A 10-year-old boy who was right handed had normal development was diagnosed with lesional right temporal lobe epilepsy. He had his first seizure at the age of 6 months during a febrile illness and continued to have febrile seizures that manifested as generalized tonic clonic seizures until the age of 6. At the age of 9, the seizures recurred. He had a total of four focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures with observable manifestations in two clusters of two seizures each.

The seizures began with a vertiginous aura with visual hallucinations of black and white shapes that the patient had difficulty characterizing but described as similar to dots. The patient gave no further specification on its location in the visual field. The auras were followed by the left eye and head turning, with fluent and comprehensive speech being maintained initially. As the seizures progressed, the patient lost consciousness. His seizures were well controlled with valproic acid, but the medication was switched to levetiracetam because of side effects— specifically increased appetite—and in preparation for discharge from the epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) before surgery. The patient had no family history of epilepsy and the findings of his clinical examination were normal.

VIDEO EEG

The patient was admitted to the EMU in King Fahad Medical City in September 2023 for presurgical evaluation. Scalp video EEG recordings acquired over 15 days were reviewed daily. Interictal baseline recordings revealed a symmetrical posterior alpha rhythm. Runs of 8–10 Hz of rhythmic right basal frontal–anterior temporal (F8) alpha activity that lasted for 3–6 s were observed exclusively during sleep. Interictal abnormalities were noted that included polymorphic delta activity activated by sleep, as well as diffuse right temporoparietal epileptiform discharges, most frequently at F8.

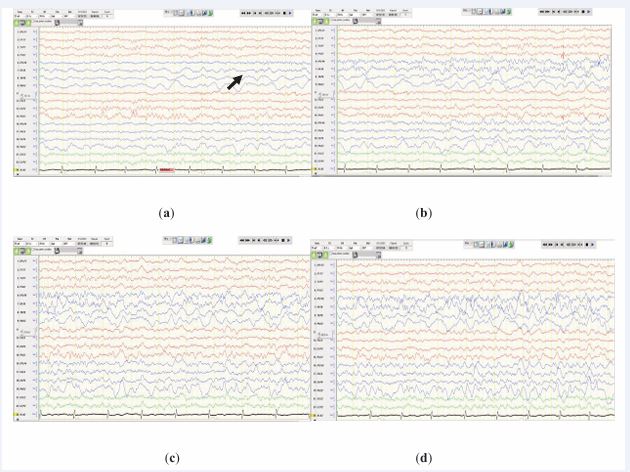

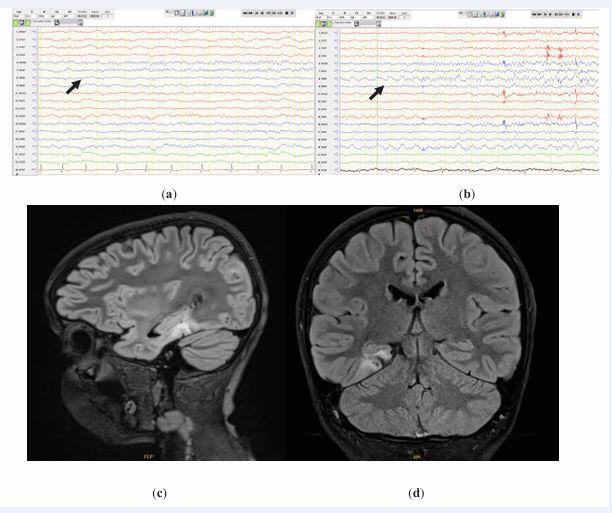

Thirty-five seizures—of which eight were electroclinical and twenty-seven electrographic—that occurred during wakefulness and sleep were recorded. Of the eight clinical seizures, three started with clear alpha activity at F8, with EEG onset preceding the clinical manifestations by an average of 30 s. Furthermore, 17 electrographic seizures started at F8 with rhythmic medium-amplitude alpha range activity (commonly 8–9 Hz) that then evolved into intermixed theta and delta frequencies, with further variable spread to adjacent regions of the head, namely, O2, P4, and F4. Examples of the ictal onset are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The onset of the remaining 15 seizures that were recorded ranged between rhythmic theta activity and ambiguous EEG onset with clear widespread localization over the entire (anterior, midtemporal, and posterior) area of the right temporal head region. Clinically, all the seizures shared the characteristics of preserved consciousness and speech, along with the eye and head deviating to the left.

Figure 1 Electrographic recording of a seizure captured during sleep (sleep spindle and vertex wave are visualized in the 7 and 8 s of the epoch) on a longitudinal bipolar montage. A 10-Hz alpha frequency, maximized at F8, is observed at onset. (a), (b), (c), and (d) represent the evolution of the seizure.

Figure 2 Two distinct clinical seizures are observed arising out of sleep. An 8-Hz alpha wave is observed at F8 at electroencephalography onset, (a) and (b); sagittal and coronal FLAIR MRI scans, (c) and (d).

with or without dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor and or ganglioglioma (Figure 2). An FDG-PET scan revealed mild asymmetrical hypometabolism within the right posterior parahippocampal region.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to intracranial EEG recordings, the description of rhythmic alpha activity as an ictal onset pattern recorded from scalp EEG is uncommon in the literature. Such activity has also not specifically been correlated with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Fast frequencies are associated with ictal onset and can be recorded at the scalp; however, they are usually in the beta range or higher. Pelliccia et al. described two distinct patterns of fast activity in temporal lobe epilepsy on scalp EEG: (1) fast activity, which is generally beta activity, and (2) low-voltage fast activity, which is fast activity associated with a clear drop in amplitude of up to 20 µV [14].

Dibek et al., reported a case of frontal lobe epilepsy with ictal alpha activity; three clinical seizures of right frontal origin were recorded. Their case differs from ours in that the alpha activity was preceded by amplitude suppression and was not the first visible change at the onset of the seizure [15].

In 57.14% of seizures, our patient demonstrated a unique pattern of ictal onset in his scalp EEG. Twenty seizures with alpha activity at onset demonstrated almost the same EEG signature, with little variability. At onset, seizures were characterized by rhythmic medium amplitude alpha activity that ranged between 8 and 10 Hz in the region of the right anterior temporal head (F8).

Our patient did not undergo surgical resection of the lesion. Hence, the accurate anatomical extension of the lesion, histopathology, and outcome cannot be predicted. Differential diagnosis of the lesion was achieved based on the radiology report, but the specific etiology of the lesion remains unclear. Alpha rhythm at the beginning of seizures may have a localization and prognostic value should the same pattern be reported in other similar cases. The possibility of ictal onset alpha activity as a pattern associated with a specific lesion warrants further investigation.

CONCLUSIONS

Our case demonstrates that ictal EEG in seizures with onset in the temporal lobe may rarely present with rhythmic alpha activity. This presentation is not indicative of a specific etiology. Further studies involving case reports, case series, and observational investigations on patients with similar presentations may aid in better characterizing and correlating this uncommon presentation of temporal lobe epilepsy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the patient and his legal guardian for allowing this publication.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD

“The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Fahad Medical City on 11 December 2023. IRB Log Number: 23-670”

IRB Registration Number with KACST, KSA: H-01-R-012

IRB Registration Number with OHRP/NIH, USA: IRB00010471

Approval Number Federal Wide Assurance NIH, USA: FWA00018774

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent for disclose was obtained from the patient’s father (legal guardian) for the publication of this case.

REFERENCES

- Ebersole JS, Pacia SV. Localization of temporal lobe foci by ictal EEG patterns. Epilepsia. 1996; 37: 386-399.

- Geiger LR, Harner RN. EEG patterns at the time of focal seizure onset. Arch Neurol. 1978; 35: 276-286.

- Nam H, Yim TG, Han SK, Oh JB, Lee SK. Independent component analysis of ictal EEG in medial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002; 43: 160-164.

- Sip V, Scholly J, Guye M, Bartolomei F, Jirsa V. Evidence for spreading seizure as a cause of theta-alpha activity electrographic pattern in stereo-EEG seizure recordings. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021; 17: e1008731.

- Abdallah C, Mansilla D, Minato E, Grova C, Beniczky S, FrauscherB. Systematic review of seizure-onset patterns in stereo- electroencephalography: Current state and future directions. Clin Neurophysiol. 2024; 163: 112-123.

- Feng R, Farrukh Hameed NU, Hu J, Lang L, He J, Wu D, et al. Ictal stereo-electroencephalography onset patterns of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and their clinical implications. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020; 131: 2079-2085.

- Patrizi S, Holmes GL, Orzalesi M, Allemand F. Neonatal seizures: characteristics of EEG ictal activity in preterm and fullterm infants. Brain Dev. 2003; 25: 427-437.

- Bauer J, Helmstaedter C, Elger CE. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus with generalized ‘fast activity’. Seizure. 1997; 6: 67-70.

- Rezazadeh A, Bui E, Wennberg RA. Ipsilateral preictal alpha rhythm attenuation (IPARA): An EEG sign of side of seizure onset in temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure. 2023; 110: 194-202.

- Pyrzowski J, Siemi?ski M, Sarnowska A, Jedrzejczak J, Nyka WM. Interval analysis of interictal EEG: pathology of the alpha rhythm in focal epilepsy. Scientific Rep. 2015; 5: 16230.

- Pataraia E, Lurger S, Serles W, Lindinger G, Aull S, Leutmezer F, et al. Ictal scalp EEG in unilateral mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1998; 39: 608-614.

- Javidan M. Electroencephalography in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2012; 2012: 637430.

- Tatum WO 4th. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2012; 29: 356-65.

- Pelliccia V, Mai R, Francione S, Gozzo F, Sartori I, Nobili L, et al. Ictal EEG modifications in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2013; 15: 392-9.

- Dibek DM, Baba C, Akbulut N, Çoban PT, Öztura ?, Baklan B. Rare Two Findings in Frontal Lobe Epilepsy: Finger Snapping, and Ictal Alpha Activity. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2021; 24: 264-266..