Healthcare Clinical Champions in Family Violence: A Pilot Study

- 1. Allied Health-Psychology & Family Safety Team, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Australia

Abstract

Rationale, aims and objectives: Healthcare services play a vital role in identifying and responding to family violence. There is a growing expectation and requirement that hospital staff has an understanding of family violence and have the skills to identify and manage disclosure. While health services have historically implemented training programs to improve the clinical skillset, it is unclear how effective these training programs have been at improving the response to family violence.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a multi-faceted family violence training program on clinician self-reported knowledge, confidence and skills.

Method: Clinical staff including allied health, emergency department nursing and care co-ordinators underwent comprehensive family violence training. Training included aspects of a clinical champion’s model, Common Risk Assessment Framework Level 3 training, monthly clinical supervision, quarterly network meetings, additional training opportunities and secondary consultations as needed. Effectiveness was measured using a modified version of the Assisting Patient/Clients Experiencing Family Violence: Royal Melbourne Hospital Clinician Survey at pre-training, post-training and two further follow up time points.

Results: Of the 45 clinicians who participated in the family safety training, 41 completed the evaluation survey at least once, with varying numbers of survey completion across the other 3 time-points. Statistically significant and sustained improvements were found in levels of self-reported family violence knowledge, confidence and frequency of screening.

Conclusion: In-depth, multi-faceted training can result in significant and sustained improvements in clinician self-rated knowledge and awareness of how to identify and respond to family violence. Change in clinical practice was further observed in clinicians’ self-reported screening for family violence. Findings from this study suggest that a multi-faceted approach to training hospital staff may increase translation of knowledge into clinical practice.

Keywords

• Delivery of Health Care

• Domestic Violence

• Hospitals

• Learning

Citation

Fisher CA, Klaic M, Withiel T (2020) Healthcare Clinical Champions in Family Violence: A Pilot Study. J Behav 3(1): 1018.

INTRODUCTION

What do we already know about this topic?

Healthcare services play a vital role in identifying and responding to family violence, with growing expectation of staff clinical skills to identify and manage disclosure.

How does your research contribute to the field?

We provide evidence to show that sustainable change in clinician knowledge, confidence and skills in managing family violence is achievable following comprehensive training.

What are your research’s implications towards theory, practice, or policy?

Developing in-depth, multi-faceted training programs that address family violence management is recommended to ensure translational clinical benefit.

The need for healthcare services to assist healthcare users experiencing family and domestic violence has become clear in recent years. State government funded wide-scale inquiries into family violence in Australian communities have identified the integral role health and hospital services play in improving the community response to this issue [1,2]. This is also well supported by research with a recent systematic review indicating that health systems have a clear role in responding to the costly problem of family violence [3]. Key areas of support identified include family violence screening for at-risk groups, risk assessment combined with safety planning and medium term counselling [3].

Effective methods to improve the healthcare response to family violence, via training of hospital staff, are less clear. Recent Australian research indicated that healthcare staff that had undertaken any form of short-duration (1 to 3 hours) family violence training reported suboptimal levels of knowledge and confidence working clinically in the area [4]. The study indicated that 7-9 hours of training was required for at least 50% percent of participants to rate their knowledge level at moderate or above, while at least 16 hours of training was required for 75% of participants to rate their knowledge level at moderate or above. For confidence ratings, 10-15 hours of training was required for at least 50% percent of participants to rate their confidence levels as moderate or above, while 16 or more hours of training were required for a minimum 75% to rate their confidence level at moderate or above [4].

This is supported by studies indicating that targeted longer duration family violence training (1 to 2 days) has some impact on self-rated knowledge levels in healthcare professionals Previous research has found that a one day educational training seminar improved midwives family violence knowledge, skills, attitudes to routine enquiry, albeit with small effect size estimates [5]. Similarly, a two-day didactic information and team planning intervention was found to be effective at improving domestic violence knowledge, attitudes, service culture and patient satisfaction in hospital emergency departments in the United States [6]. However, this training did not result in an improvement in the rates of identification of domestic violence in female service users. Improvements in health professionals’ knowledge has also been reported, in the short term, following a one-day domestic violence training session in a British maternity and sexual health service [7]. Some degree of practice change was also reported following this training, including improving enquiry skills. However, universal screening was not achieved, even with organisational support (via the implementation of guidelines, training and advocacy) and the authors reported that potential and actual harm occurred during the intervention. This included breaches of confidentiality, failure to document evidence, negative labelling and stereotyping from staff. Overlooking significant risk was also reported, as a patient with a baby was discharged to a home environment with an abusive partner, even though these details were known to the health service.

Research has also been conducted on the efficacy of a training workshop (duration unclear) to improve Australian clinical hospital staff knowledge about family violence and accessing available legal service pathways for clients [8]. The results indicated that training was effective at improving self-reported knowledge of, and confidence in, responding to family violence and understanding of lawyers’ roles within the hospital. The training did not, however, result in an increase in referrals to the hospital’s legal assistance service. Thus, it appears that self-reported knowledge and attitudes can be modified through family violence training, but that improvements in clinical practice are less consistent.

The idea of clinical or organisational champions within healthcare is not new [9]. Champions models have been used in stroke care, hand hygiene, telehealth care, malnutrition and rapid response teams, to name just a few [10-14]. Champion models can take a number of forms, however the majority involve selected staff leading transformation change projects designed on evidence based best practice, to improve healthcare service in specific areas. Champion led programs have been shown to be most effective in the first phase of initiative adoption and are more effective when project champions work in partnership with organisational change champions [14,15].

The current project was funded by the Strengthening our Hospital’s Response to Family Violence (SHRFV) initiative, established by the Victorian State Government to implement healthcare recommendations from the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence [16]. The key tenets of this initiative are to train front line public health workers to identify the signs of family violence in patients, to respond appropriately, and for health workers to receive support to do this work effectively, consistent with recent practice recommendations informed by research in the sector [16]. To our knowledge, a clinical champion model for family violence training in hospital clinicians has yet to be reported in the literature. In the current study, we report pilot data from research into the efficacy of a family violence clinical champion’s initiative implemented at a large metropolitan adult hospital in Australia. A clinical champions model was adopted, founded around in-depth training, and implemented in response to the evidence that short-duration training in family violence may be of limited utility for clinical staff at the hospital [4]. The in-depth training was accompanied by a peer support network, supervision and ongoing training in an attempt to improve the efficacy and clinical utility of the champions’ initiative.

The champions’ initiative was termed the ‘Family Safety Advocates Network’, and the trained champions ‘Family Safety Advocates’. The term ‘champions’ was deliberately avoided by the initiative team as the hospital already had a number of ‘champion’ programs in other clinical areas, such as hand hygiene, and differentiation from existing initiatives was desired. The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of longer-duration family violence clinical training on clinician self-reported knowledge, confidence, family violence clinical skills and subsequent improvements in clinical practice.

METHOD

Design

This pre-post, prospective, interventional study design sought to explore effectiveness of training at three time points: 1 to 4 weeks post-training, 6-9 month follow-up and 12-15 month follow-up. The Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE(17)) were consulted in reporting findings from this study (see Appendix A).

Participants

Clinical staff from the areas of Allied Health (including Social Work, Psychology, Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy) and Emergency Department Nursing and Care Co-ordination, self-selected via expressions of interest to their profession manager to be trained as [Hospital Name] Family Safety Advocates. Prior to being accepted into the advocates training program, all candidates underwent a 1:1 interview with a member of the initiative team to ensure that they were aware of what the role entailed, including how they would manage working clinically in the area of family violence from a psychological perspective, if they were comfortable accessing the peer support network that would be set up, and if they were comfortable advocating to keep family violence on the agenda in their clinical teams.

Training Intervention

Aspects of the clinical champions model outlined by Soo and colleagues [13] were adapted for use with the Family Safety Advocates training. Soo et al., described four key features of Things that Champions Do, including educate, advocate, build relationships and navigate boundaries. The primary focus for the [Hospital Name] Family Safety Advocates training program was to train advocates in evidence based, best-practice model of healthcare workers responses for assisting patients experiencing family violence. Family Safety Advocates were trained in a two-stage process, totalling 9.5 hours of training. The first was an in-house hospital-based organisation training seminar of 3 hours in duration. The training in this seminar was based on Modules 1 and 2, and the Elder abuse training from The Royal Women’s Hospital Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence (SHRFV) Tool Kit (https://www.thewomens.org. au/health-professionals/clinical-resources/strengthening-hospitals-response-to-family-violence). Topics covered included: Introduction to family violence (definition, statistics, Victorian Royal Commission findings, family violence signs and examples), healthcare response, hospital procedure and guideline, [Hospital Name] staff and patient family violence research findings, sensitive practice (sensitive enquiry), assessing risk, action plans, referrals and police/legal involvement, staff support and resources. Discussion on how to raise and advocate for family violence issues in clinical teams was also discussed, education provided about key linked networks within the hospital, and support pathways to the hospital’s Family Safety Team when problems, resistance, or boundaries to providing support for patients, were encountered.

Advocates also underwent the state-wide industry leading training in the Common Risk Assessment Framework Level 3 (CRAF3) of 6.5 hours duration. This training involved: introduction to family violence risk assessment and management framework; shared understanding of family violence, specialist family violence risk assessment; risk management, safety planning; referral pathways, information sharing and networking. This training was interactive and allowed participants to role play clinical scenarios. The CRAF3 training was run by an external provider (the state industry lead organisation: Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria, https://www.dvrcv.org.au) on site at the hospital, and totalled 6.5 hours of training, over one day.

Once trained, the advocates network were provided with the opportunity to attend monthly drop-in family violence clinical supervision provided by a member of the Family Safety Team (senior social worker, or psychology head of service). They were also provided the opportunity to attend quarterly network meetings which involved the provision of further training via one hour seminars with external guest speakers in the field (family violence organisations, legal service and police force, indigenous family violence support organisation, men’s behaviour change program), as well as a full day workshop on working with perpetrators, over the following 15 months. A further additional resource was the provision of secondary consultations, via the family safety team telephone line, available during weekday business hours. This was available to all staff members of the health service, seeking advice to assist with family violence issues being experienced by their patients.

Assessment tool

The implemented assessment measure was based on the Assisting Patient/Clients Experiencing Family Violence: Royal Melbourne Hospital Clinician Survey (RMH FV Clinician Survey) [4]. Questions 1-2, 4-10, of the survey were implemented with advocates at every time point (pre-training, 1 to 4 weeks post-training, 6-9 month follow-up, 12-15 month follow-up), along with tailored questions regarding training at specific time points (e.g. information about previous training at the pre-training phase, and information about attendances at network meetings and feedback about the training at later time points). The RMH FV Clinician Survey has previously been administered to 534 clinical general hospital staff [4], as well as to 35 predominantly clinical staff at a Child and Family Health Service [18]. The survey was administered online, via emailed survey link and responses were anonymous. However, respondents were tracked for their individual responses through the follow-up period using a unique code generated by their profession, years of experience, and training date.

Statistical Methods

Data analyses were conducted using Stata Statistical Software v14.2 (StataCorp., Texas, USA). A 2-sided alpha value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Changes in self-reported rates of knowledge, confidence, screening and frequency of working with clients who disclose were analysed using a Skilling-Mack Test [19]. This non-parametric inferential analysis was chosen due to its robust ability to manage small sample sizes and missing data points. This allows for all data points to be included in the analysis, even those of respondents with missing data points. Dunn’s post hoc testing with Bonferroni correction were computed to explore differences between time points. Treatment effect size, defined as the magnitude of change from baseline, was estimated with Kendall’s W [20].

To examine change in nominal data over time (specifically, knowledge of indicators of family violence, ability to ask about family violence and management of disclosures), a series of exact Cochran’s Q analyses with planned contrasts were conducted. Data was re-coded into a dichotomous scale by grouping responses of ‘yes’ and ‘somewhat’ into a single response category.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the [Health Service] Research and Ethics Committee (Reference Number: XX.XX).

RESULTS

A total of 45 Family Safety Advocate trainees were invited to participate in the training evaluation survey from the first three cohorts of advocate training at the health service. One advocate trainee opted not to continue as an advocate after completing their training, and several advocates left the health service during the follow-up period. Participation was inconsistent across the assessment time points, with the pre-training yielding the lowest number of respondents and the 6-9 month and 12-15 month post training time points yielding the highest levels of participation (see Table 1). The lower pre-training baseline response levels are explained by the survey link malfunctioning when sent out at baseline for one training cohort, and additional reminders to fill the survey in prior to training not being sent to another cohort. A total of 41 trainees filled in the survey at least once during the evaluation period. Seven trainees filled in the survey at all four time points, 14 at three time points, seven at two time points, and 13 at one time-point. At the 6-9 month post training time point, 57% of respondents (16/28) had attended at least one Family Safety Advocate network seminar in the follow-up period. At the 12 to 15 month post training time point, 64% (18/28) had attended at least one network meeting or seminar in the follow-up period. Eight advocates had attended one seminar, four had attended two, five attended three, and one had attended all six seminars (M 1.32; SD 1.44).

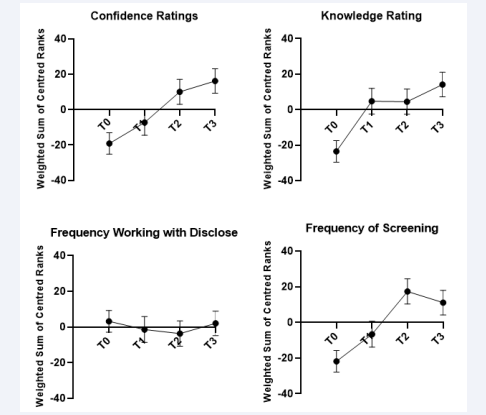

There was a statistically significant and sustained improvement in levels of self-reported family violence knowledge over time (Skilling Mack = 16.05, p< .001, corrected for ties, W = .604). Weighted sum of centred ranks and standard errors for each time point are presented in Figure 1. Post-hoc analysis demonstrated that there was a significant improvement in post training (1 to 4 weeks post), follow up one (6-9 months) and follow up two (12-15 months) relative to baseline, with p< .001 at all comparisons. A similar pattern of change was declared for self-reported confidence, with significant improvement seen over time (Skilling Mack = 14.62, p < .001, corrected for ties, W = .708; see Figure 1). Post-hoc analysis revealed that there was a significant improvement in confidence between baseline and follow up one (p = .01) and follow up two (p < .001). In terms of frequency of screening, there was a statistically significant increase in self-reported screening rates over time (Skilling Mack = 17.70, p< .001, corrected for ties, W = .596; see Figure 1). Post-hoc analysis indicated that there was a significant increase in screening rates between baseline and follow up one (p < .001) and two (p = .002). In addition, there was a further significant increase in screening rates between post training and follow up one (p = .05). Finally, there was no significant change in frequency of working with clients who have disclosed family violence between time points Skilling Mack = 0.503, p = .82, corrected for ties, W = .082; see Figure 1).

There was a significant improvement in the proportion of staff who could ask about the presence of violence, χ2 (3) = 12.00, p = .007. Pairwise comparisons indicated improvement between baseline and post-intervention (p = .028), follow up one (p = .005), and follow up two (p = .028). There was also a significant improvement in the proportion of staff who were able to identify indicators of violence over time χ2 (3) = 12.00, p = .007, with improvement seen at post intervention, follow up one and two relative to baseline (with p = .005 for all comparisons). Finally, there was a significant improvement in the ability to manage disclosures, χ2 (3) = 9.00, p = .029, with a greater proportion of participants who could manage disclosure seen at post intervention (p = .014), follow up one (p = .014) and final follow up (p = .014) relative to baseline.

Table 1: Response rates by evaluation time point and profession.

| Profession | Pre-Training | Post-Training | 6 – 9 months | 12 – 15 months |

| SW | 3 | 6 | 11 | 11 |

| OT | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| SP | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Physiotherapy | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Music Therapy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pastoral Care | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| P&O | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Nutrition | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interpreters | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Psychology | 0 | 6 | 5 | 9 |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 25 | 28 | 28 |

| SW: Social Work; OT: Occupational Therapy, SP: Speech Pathology; P&O: Prosthetics and Orthotics | ||||

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to explore the effectiveness of in-depth, multi-faceted family violence training on clinician self-reported knowledge, confidence, family violence clinical skills and subsequent change in clinical practice. Statistically significant and sustained improvement was found in self-ratings of clinical knowledge, how to ask patients about family violence, awareness of family violence indicators, and how to respond to disclosures. Improvement in these areas was maintained over the 12 to 15 month follow-up period, reinforcing the sustainability of intervention gains. Results are consistent with existing literature which indicates that longer duration training can be effective at improving self-rated family violence knowledge in healthcare professionals [6,7]. Findings are also consistent with research showing that post-training knowledge gains can persist at 12 months or more [6].

Improvements in self-ratings in the areas of confidence levels working clinically in the area family violence and family violence screening, showed a slightly different trajectory. These ratings trended towards improvement at 1 to 4 weeks post training, but did not show significant improvement from baseline until 6 to 9 months after training. This improvement was then maintained at 12 to 15 months follow-up. This suggests that family safety advocates acquired family violence knowledge during the

|

Table 1: Response rates by evaluation time point and profession. |

||||

|

Profession |

Pre-Training |

Post-Training |

6 – 9 months |

12 – 15 months |

|

SW |

3 |

6 |

11 |

11 |

|

OT |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

|

SP |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

Physiotherapy |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Music Therapy |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Pastoral Care |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

P&O |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Nutrition |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Interpreters |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Psychology |

0 |

6 |

5 |

9 |

|

Other |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

16 |

25 |

28 |

28 |

|

SW: Social Work; OT: Occupational Therapy, SP: Speech Pathology; P&O: Prosthetics and Orthotics |

||||

Figure 1: Weighted sum of centred ranks and standard errors of respondents’ ratings of their family violence clinical skills T0 = Baseline (Pre-Training) T1 = Post Intervention (1 to 4 weeks post) T2 = Follow up one (6-9 months) T3 = Follow up two (12-15 months)

training, but that it took time and regular content exposure for clinicians to implement these skills into their clinical practice regularly, and to in turn, become more confident in their abilities working in the area. Findings are of particular relevance given the importance of clinician confidence in screening. Research suggests that perceived clinician confidence plays a key role in supporting victim survivor disclosure [19], with best outcomes seen among clinicians who are comfortable and confident in their inquiry.

It is possible that the family violence topic seminars that were offered to the family safety advocates over the 12 to 15 month follow-up period also had some impact on improving confidence ratings and screening levels. The majority of respondents at 12 to 15 months follow-up had attended at least one of these sessions. These seminars may have helped to keep the advocates engaged with the program over the follow-up period. This may have kept the topic at front of mind, thus increasing the likelihood of ongoing implementation of their family violence clinical skills in their healthcare practice. Provision of ongoing access to the family safety team and a forum in which to discuss family violence issues with other advocates may have also contributed to improved confidence ratings.

Of translational significance, changes in clinical practice were observed over time with a notable increase in self-reported screening for family violence. Prior studies in this field have typically resulted in some improvements in knowledge and confidence but this has not always translated to practice change [6,7]. The training program implemented in this study included a variety of approaches such as education, champions, clinical supervision and a community of practice. It is possible that these additional elements supported clinicians to implement the acquired knowledge and confidence into everyday clinical practice. Findings further highlight the disconnect between knowledge provision and subsequent clinical implementation. Available literature suggests that uptake of clinical best-practice strategies requires more than just mandated training and policy implementation [21]. In a recent systematic review, Boaz and colleagues (2011) [22] identified the utility and effectiveness of multifaceted interventions in achieving behaviour change, above and beyond one-dimensional training approaches. Our findings are consistent with this notion and further reinforce the importance of a varied approach to ensure meaningful change in clinical practice.

The only area in which no change in ratings was obtained was to the question: How often do you work with patients/clients who have disclosed family violence, to your knowledge? At some level this result appears out of keeping with the self-reported increase in family violence screening levels i.e. if advocates are screening clients more often, then they are likely to be aware of more clients they work with having disclosed family violence experiences. However, it is possible that advocates interpreted this to refer to self-initiated (unprompted) disclosure in clients, rather than disclosures received following sensitive inquiry initiated by the advocate (champion). Or, it may have been interpreted as referring to clients that had a history of family violence disclosure that was known in the treating team, prior to the advocate (champion) themselves becoming involved with the client. With either of the above interpretations, the ratings to this question may be more likely to remain stable over time.

There are limitations of the study. One of these is the ability to quantitatively confirm objective practice change, and whether training has improved care, from a client perspective. An earlier study at the same healthcare service examined the process of family violence screening and the clinical response to disclosures from the patient perspective [23]. It is not possible to determine, from the current study, whether the clinical response provided by the family safety advocates (clinical champions) resulted in improvements from a consumer perspective. However, future research may be able to determine this at a broad-based and systems level. A follow-up evaluation to the above described patient study is planned, and may help to determine if there is a difference in screening rates, and the acceptability of the clinical response to disclosures, in hospital areas with a high number of clinician advocates, compared to those with fewer advocates. It should also be noted that clinicians self-selected to training as family safety advocates and to participate in the survey. Thus the results may reflect a cohort of clinicians with a higher level of interest and engagement in the area.

Another limitation of the study is the inconsistent response rates across study time points, and the atypical, upward trending participation rate, something that is uncommonly observed in longitudinal surveys [24]. The low baseline pre-training participation rate was due to several factors including a survey web link malfunction for one trainee group, and a failure to send pre-training secondary reminders to complete the survey, for another. However, the baseline pre-training results that were obtained were largely consistent with a previous whole-of-hospital clinician survey, that used the same measure in a clinician cohort with low family violence training levels [4]. Further, robust statistical analysis was undertaken to minimise the impact of the responding rate differences across time points. The comparatively good retention of participation through the latter two time-points of the study (62% for both, respectively) may indicate that the family safety advocates (clinical champions) remained well engaged with the initiative and thus, continued to be prepared to fill in the survey at subsequent time-points, when asked.

To our knowledge, this pilot study is the first to evaluate the effectiveness of clinical champions training for family violence in healthcare. Findings suggest that this model may be effective and improving family violence knowledge and clinical practice in a group of mixed (mainly allied health) hospital clinicians. However, these findings are considered tentative given the relatively small sample size. Future research should seek to replicate findings in a larger sample size. Moreover, it would be useful to explore the utility of this training approach in other settings. Family violence clinical skills will continue to be important for healthcare professionals, whilst rates of family violence in the community remain high.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors have approved the final article. CF conceived, planned and conducted the study. CF, TW and MK performed the analyses. All authors wrote the manuscript and contributed to interpretation of the analyses and critical revision. We would like to thank the Royal Melbourne Hospital Family Safety Advocates for their participation, and the Royal Women’s Hospital and the Domestic Violence Resource Centre for the development of some of the training materials/content.

This study was supported by Victorian State Government via Department of Health and Human Services-Strengthening Hospital Responses to Family Violence Initiative.

| Title and Abstract | Description | Page of Inclusion |

| 1. Title | Indicate that the manuscript concerns an initiative to improve healthcare (broadly defined to include the quality, safety, effectiveness, patient-centeredness, timeliness, cost, efficiency, and equity of healthcare) | Title page |

| 2. Abstract | a. Provide adequate information to aid in searching and indexing b. Summarize all key information from various sections of the text using the abstract format of the intended publication or a structured summary such as: background, local problem, methods, interventions, results, conclusions |

Page 1 |

| Introduction | Why did you start? | |

| 3. Problem Description | Nature and significance of the local problem | Page 3 |

| 4. Available knowledge | Summary of what is currently known about the problem, including relevant previous studies | Pages 3-5 |

| 5. Rationale | Informal or formal frameworks, models, concepts, and/or theories used to explain the problem, any reasons or assumptions that were used to develop the intervention(s), and reasons why the intervention(s) was expected to work | Page 5 |

| 6. Specific aims | Purpose of the project and of this report | Page 5 |

| Methods | What did you do? | |

| 7. Context | Contextual elements considered important at the outset of introducing the intervention(s) | Page 6 |

| 8. Intervention(s) | a. Description of the intervention(s) in sufficient detail that others could reproduce it b. Specifics of the team involved in the work |

Pages 6-8 |

| 9. Study of the Intervention(s) | a. Approach chosen for assessing the impact of the intervention(s) b. Approach used to establish whether the observed outcomes were due to the intervention(s) |

Pages 9 |

| 10. Measures | a. Measures chosen for studying processes and outcomes of the intervention(s), including rationale for choosing them, their operational definitions, and their validity and reliability b. Description of the approach to the ongoing assessment of contextual elements that contributed to the success, failure, efficiency, and cost c. Methods employed for assessing completeness and accuracy of data |

Page8 |

| 11. Analysis | a. Qualitative and quantitative methods used to draw inferences from the data b. Methods for understanding variation within the data, including theeffects of time as a variable |

Page 9 |

| 12. Ethical Considerations | Ethical aspects of implementing and studying the intervention(s) and how they were addressed, including, but not limited to, formal ethics review and potential conflict(s) of interest | Page 9 |

| Results | What did you find? | |

| 13. Results | a. Initial steps of the intervention(s) and their evolution over time (e.g., time-line diagram, flow chart, or table), including modifications made to the intervention during the project b. Details of the process measures and outcome c. Contextual elements that interacted with the intervention(s) d. Observed associations between outcomes, interventions, and relevant contextual elements e. Unintended consequences such as unexpected benefits, problems, failures, or costs associated with the intervention(s). f. Details about missing data |

Pages 9-11 |

| Discussion | What does it mean? | |

| 14. Summary | a. Key findings, including relevance to the rationale and specific aims b. Particular strengths of the project |

Page 12 |

| 15. Interpretation | a. Nature of the association between the intervention(s) and the outcomes b. Comparison of results with findings from other publications c. Impact of the project on people and systems d. Reasons for any differences between observed and anticipated outcomes, including the influence of context e. Costs and strategic trade-offs, including opportunity costs |

Page 12-15 |

| 16. Limitations | a. Limits to the generalizability of the work b. Factors that might have limited internal validity such as confounding, bias, or imprecision in the design, methods, measurement, or analysis c. Efforts made to minimize and adjust for limitations |

Page 14-15 |

| 17. Conclusions | a. Usefulness of the work b. Sustainability c. Potential for spread to other contexts d. Implications for practice and for further study in the field e. Suggested next steps |

Page 15 |

| Other information | ||

| 18. Funding | Sources of funding that supported this work. Role, if any, of the funding organization in the design, implementation, interpretation, and reporting | Page 5 |