Social and Behaviour Change Interventions to Reduce School Drop-Out and Improve School Retention and Completion among School-Aged Children and Youth in Low -and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review

- 1. School of Public Health, Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

- 2. Communication Partners International (CPI) Sydney, Australia

- 3. Dow Institute of Health Professionals Education, Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan

- 4. UNICEF, Tanzania

- 5. Jamii Integrated Development Initiative Limited (JIDI), Tanzania

Abstract

Objective: This systematic review synthesises international evidence on behavioural and programmatic factors leading to the success of child and youth school retention and completion in low -and middle-income countries (LMICs) to inform policy and social and behaviour change (SBC) interventions.

Data sources: The study follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines with the proposal registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database.

Search strategy: A systematic search was performed on PubMed, ERIC, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases for articles published from Jan 2015 to July 2024. Study selection: Reviewers independently completed screening procedures and reviewed eligible publications focusing on LMIC policy frameworks, cultural, gender, socioeconomic, infrastructural, human resource and geographic factors impacting school drop-out and SBC interventions.

Data synthesis: SBC was rarely mentioned in intervention approaches, despite SBC activities being identified in programs targeting out of school children (OOSC), including training and capacity building, identification of key influencers, and the development of purposive SBC interventions. Facilitators to improved engagement and student retention included teacher training and capacity building, the use of structured syllabus, and targeting of participants from the education supply and demand sides. Cash transfer programs generally demonstrated positive impacts on student retention and reduced drop-out, including nutrition incentives in and out of schools.

Conclusion: Complementary multipronged and multilevel SBC approaches that create greater engagement and partnerships with parents, teachers and the communities they serve, are a likely to achieve the greatest traction in addressing challenges of OOSC.

PROSPERO registration ID: (anonymized for review)

Keywords

• Out-of-school children • School dropout • School retention • Social and behavior change communication • Low-and middle-income countries

Citation

Tahir T, Shafiq K (2025) Social and Behaviour Change Interventions to Reduce School Drop-Out and Improve School Retention and Completion among School-Aged Children and Youth in Low -and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. J Behav 8(1): 1026.

INTRODUCTION

Children dropping out of school before completion of primary or secondary studies is a problem for educationalists in many countries, but more so in low -and middle-income country (LMIC) contexts. UNESCO reports the number of out-of-school children (OOSC), has risen by 6 million since 2021 and now totals 250 million dropouts or non-attendance globally [1]. This accounts for 16% of children and youth in primary to upper secondary level not attending school, with 1 in 10 children worldwide not being in school at primary level with 122 million, or 48% of the out-of-school population being girls and young women [1]. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for close to 30% of all OOSC globally with 1 in 5 African children not attending school (19.7%) and only around 50% of children attending upper secondary school [1,2]. Some of the key drivers of OOSC identified by UNICEF include household poverty, long distances to school, lack of tailored inclusive services for vulnerable children, including those with disabilities, and deeply rooted social norms that undervalue education. Furthermore, the lack of gender-sensitive/responsive school WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) facilities and menstrual and hygiene services have also been found to exacerbate school dropout, especially for girls [3]. Coupled with these challenges the COVID-19 pandemic has also reversed the gains made despite efforts made by government and development partners to establish and provide access to alternative learning pathways [4 ]. UNICEF continues to support African countries toward the improvement of educational and nutrition outcomes for children with projects in Tanzania, and other African countries. In Tanzania, the nation’s emphasis, like many other sub-Saharan African countries focusses on achieving educational goals, ranging from universal primary school enrollment to ensuring free and equal access at all levels. This commitment aligns with Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), and Tanzania’s pledge to offer free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education to all children by 2030 through the Education Sector Development Plan [5 ]. Despite the implementation of the Fee-Free Basic Education (FFBE) policy in 2016, which significantly increased net enrollment rates, challenges persist. While primary school enrollment rose from 84% in 2016 to 95.3% in 2020, 3.6 million children of school-going-age remain out of school, with 37.5% having never attended. Dropout rates – particularly between standard 6 and 7 – pose a concern, with reported reasons including a perceived ‘lack of interest’ in continuing education, and costs such as school uniforms, learning materials, food, etc. remaining challenges to the very poor [2,6]. Other identified barriers include violence against adolescent girls [7], while education itself has also been identified as a protective factor against violence [8 ,9]. Implementation of FFBE has been seen to have a positive impact on enrollment rates, especially among vulnerable groups, thereby reducing the financial burden on families [10], However, challenges persist, including overcrowded classrooms, increased teacher workloads, and a decline in parental involvement, reflecting communication gaps and misunderstandings about the policy [7]. Attitudinal or perceptual determinants-particularly loss of interestsignificantly contributes to school dropouts, with studies indicating a greater impact on boys influenced by economic activities; family structure; peer pressure; early partner pregnancies; and early marriages [11,12]. Against this backdrop, the Government of Tanzania with support of UNICEF (Tanzania), and their partners, are looking to integrate a comprehensive, evidencebased Social and Behaviour Change (SBC) strategy to educational interventions, to address the issue of OOSC in Tanzania. SBC works to provide scientific insights to give communities more control over the decisions that affect their lives. This is best achieved through the recognition that changing knowledge isn’t enough to change behaviours with the approach focussing partnerships with families and community leaders on understanding their needs, identifying their strengths and lower barriers to positive change in the environments in which they act, making it easier for communities to adopt protective practices for their children [13]. Systematic reviews more often focus on creating a taxonomy of a body of research to advance a thesis and provide a foundation for future investigations [14]. However, systematic reviews can also provide valuable tools, coupled with a strong evidence base to inform the design and operationalising of educational and other health interventions that are in urgent need in LMICs. This systematic review explores the current literature to inform SBC interventions to enhance enrollment and retention rates with children, ultimately contributing to the overarching goal of achieving universal basic education in Tanzania and other LMICs, with a focus of the review being on developments since FFBE was implemented in 2016.

Systematic Review question(s) To explore PI(E)COS criteria (Populations (P), Interventions/Exposures (I/E), Comparators (C),Outcomes (O), and Study designs or Settings (S) as follows:

RQ1: What SBC interventions have been the most successful in in LMICs to reduce child and youth school drop-out, and improve retention and completion?

RQ2: What are the determinants associated with the enrolment and retention of OOSC in primary and lower secondary school?

RQ3: How do social/ cultural norms, attitudes, perceptions, and social structures impact on school participation among primary and lower secondary schoolaged children?

RQ4: How effective are the existing policies and interventions in addressing the challenges faced by OOSC?

RQ5: What are the key challenges and opportunities associated with alternative education models for OOSC?

RQ6. Of the programs demonstrating positive outcomes how did their effectiveness vary by the type and scale ofthe interventions, and student sociodemographic and cultural backgrounds?

METHOD

This systematic review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The proposal was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database before conducting the review. (Review ID: CRD42024549293).

Search Strategy

A systematic search was performed extensively on PubMed, Education Abstracts, ERIC, PsycINFO, Web of Science, EMBASE, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases for articles published from Jan 2015 to July 2024. Articles published from 2015-2024 were considered given that 2015 was the year when many African countries commenced implementation of fee-free basic education (FFBE), as part of the “leaving no one behind” campaigns. In addition to the identified databases, reference lists of recent and relevant systematic reviews/meta-analyses and references cited in the relevant original articles were also screened for studies not found in the main search strategy.

The final search was conducted by combining individual search results and combining them with appropriate Boolean operators (“OR” and “AND”). Search results were imported into EndNote® version X7 software (Thomson Reuters, New York, USA) in EndNote library file (.enl) format and any duplicate studies were removed. URL to search strategy: Key words included: Social Behaviour Change AND School Drop-out OR Out-of-school children AND Basic Education AND Low -and Middle-Income Countries OR Developing Countries (see Appendix 1. Short Version of SRMA Search Terms/ Detailed Version of Search Terms).

Selection Protocol

Two reviewers (anonymized) conducted the search protocol independently with predefined search terms and strategies from databases of the published peerreviewed literature for potential inclusion in the review. ### meticulously searched for the literature while ### repeated the searches and both authors approved all studies that were included in the final synthesis. A third investigator ### settled any differences between the two investigators during the entire selection process. All review process.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Eligibility criteria were formulated as per PI(E)COS criteria (Populations, Interventions/Exposures, Comparators, Outcomes, and Study designs or Settings. The study population (P) will be deemed school-going children, and those dropped out of school children/youth residing in low-and middle-income countries. Interventions/ Exposures (I/E) will focus on social and behaviour change (SBC) interventions implemented within and outside of the school settings targeting the populations of interest, the scale of the interventions and the reach to program target groups. Comparators/Controls (C) will explore the different types of intervention approaches including interpersonal, community, social media and mass media approaches and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which identify comparisons of changes with control groups.

Outcomes (O) will examine factors such as school retention rates, dropout from school, change in dropout rate, reenrolments and year of completion including changes in SBC indicators of program awareness, knowledge, attitude and perceptions, intentions and behavioural changes resulting from program awareness. Study designs or settings (S) will include experimental designs, inclusive of RCTs, cluster-controlled trials along with descriptive observational studies measuring program outcomes based on a pre-delivered interventions or programs. Settings for inclusion will include any studies or interventions conducted in LMIC contexts. Additionally, only peerreviewed journal articles, written in English, were to be included in the review. Studies published only from 2015-2024 will be included considering comprehensive SRMAs conducted examining school drop-out and retention interventions prior to this period, and the introduction of free universal primary education from 2015 in East African countries and other LMICs. Interventions based on educational programs in high income country settings will be excluded considering the different challenges faced by resource constrained LMIC contexts. Commentaries, editorials, letters to editors, correspondence, books, conference proceedings, and review studies will also be excluded.

Risk of Bias Assessment

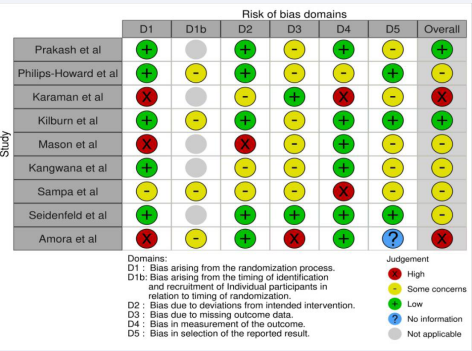

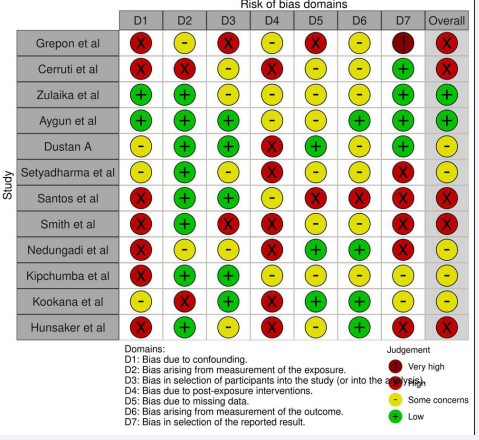

In this systematic review, the risk of bias of the included studies was assessed using the Risk of Bias (ROB-2) tool for Cluster Randomized Controlled Trials [15]. This tool evaluates key domains for potential biases, randomization process, timing of identification and recruitment of individual participants in relation to timing of randomization, deviations from intended intervention, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of reported results [14]. Each domain was judged as having a low, some concerns, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias. For studies which used observational design, the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies – of exposure (ROBINS-E) tool was used [16], ROBINS-E focusses on seven domains in terms of bias assessment including – bias due to confounding, measurement of exposure, selection of participants into the study or analysis, post-exposure interventions, missing data, measurement of outcome and selection of the reported results [17].

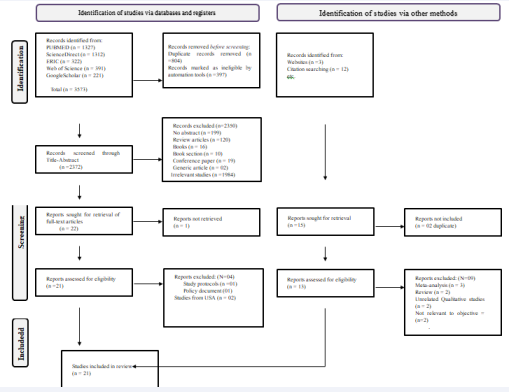

Two reviewers (##, ###) independently performed the risk of bias assessment for all included studies. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (##) when necessary. The results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in Figures 1,2, which provide an overview of the risk of bias across studies for each domain.

RESULTS

Search Overview

The extensive database search yielded 3,573 publications. Twelve other studies were identified from searching other websites and citations. After removing 804 duplicate records and another 397 records marked as ineligible by automation tools or not retrieved, 2,372 titles and abstracts were reviewed, out of which 1,984 papers were irrelevant, 199 had no abstracts available, 120 were review articles, 16 were books, 10 were book sections/chapters, 19 were conference papers, 02 were generic articles, 01 full text couldn’t be retrieved and were thus excluded. The remaining 21 full texts were reviewed based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of these, 17 papers were retained for full text review. Another 15 articles were identified through a reference search of relevant articles and reviews; of these 4 full text articles were found eligible for inclusion. Therefore, a total of twenty-one (N=21) studies met the study eligibility criteria and were included in the final sample. The PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1. provides the details of inclusion and exclusion of studies.

Figure 1 PRISMA flowchart identifying and screening studies, eligible and selected studies (n=21).

Study characteristics

Of the 21 studies from January 2015-June 2024 selected for the final review, studies from 11 countries globally were identified. Most of the studies (n=10) were from the African region – Kenya (n=3): (Phillips-Howard P, Nyothach E, Kuile FO, et al.; 2016; KangwanaI B, Austrian K, Soler-Hampejsek E, et al.; 2022; Zulaika G, Bulbarelli M, Nyothach E, et al.; 2022); Malawi (n=2): (Kilburn K, Handa S, Angeles G, et al.; 2017; Hunsaker S.; 2018); Sierra Leone (n=2): (Mason M, Galloway D.; 2020; Smith WC.; 2022). Somalia (n=1): (Kipchumba E, Sulaiman M.;2017); Zambia (n=2): (Sampa M, Jacobs C, Musonda P.; 2018; Seidenfeld D, Prencipe L, Handa S.; 2015). Other study locations included India (n=4): (Prakash R, Beattie TS, Javalkar P, et al.; 2019; Amora YB, Dowden J, Borh KJ, et al.; 2020; Nedungadi P, Mulki K, Raman R.; 2016; Kookana RS, Maheshwari B, Dillon P, et al.; 2016); Latin America (n=3) Brazil: (Santos FM, Corseuil CHL.; 2022), Argentina/Brazil/Mexico: Cerutti P, Crivellaro E, Reyes G. et al.; 2019; Mexico: (Dustan A.; 2019); Philippines (1): (Grepon BG, Cepada CM.; 2021); Turkey (n=2): (Karaman 0.; 2022; Aygün AH, K?rdar MG, Koyuncu M, et al.; 2024); and Indonesia (n=1): (Setyadharma A.; 2018).

Study characteristics varied, with a half (n=10) of the studies focussing on evaluating data from high-quality RCTs with robust sample sizes for population level assessments of findings including, quasi-experimental and experimental designs or mixed methods approaches. Evaluation designs, longitudinal studies and time-series analysis accounted for the other half of the of studies reviewed (n=10). Five (n=5) of the total 20 studies, focussed on evaluation of conditional and unconditional cash transfers on student retention and drop-out. A summary of the final 21 studies selected, according to their type, and the calibre of the studies, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary of key characteristics of selected SBC interventions studies and outcomes addressing OOSC according to study type and author’s alphabetical listing. (n=21).

|

S. No./ Ranking/ Relevance1 |

Authors/Year of Publication/ Title |

Study Design/Location/ Country |

Target Population/ Participants, Sample Size & Intervention Period |

Outcome Assessed |

Key Findings and Recommendations |

|

1. Randomised Control Trials (RCTs), Quasi-Experimental and Experimental Designs (n=10) |

|||||

|

1. ***** |

Prakash R, Beattie TS, Javalkar P, et al. (2019). The Samata intervention to increase secondary school completion and reduce child marriage among adolescent girls: results from a cluster randomised control trial in India. |

80 of 121 villages in Vijayapura and Bagalkote districts, Karnataka State, India, were randomly selected (40 villages in control and 40 in intervention areas. Girls were enrolled and followed for 3 years (2014-2017) until the end of secondary school (standard 10th grade). Analyses were intention-to- treat and used individual- level girl data. |

All 12–13-year-old adolescent girls in final year of primary school (standard 7th) in scheduled caste/tribe villages in Karnataka. Conducted from 2014- 17. |

Primary trial outcomes were the proportion of girls who completed secondary school and were married, by trial end-line (15-16 years). |

Small but significant increases in secondary school entry (adjusted odds ratio AOR = 3.58, 95%, CI = 1.36-9.44) and completion (AOR=1.54, 95%CI = 1.02-2.34) in one district although the sensitivity and attrition analyses did not impact the overall result indicating that attrition of girls at end-line was random without much bearing on overall result. Lower than expected school drop-out and child marriage rates at end-line reflect strong secular changes, likely due to large-scale government initiatives to keep girls in school and delay marriage. Recommendations are that although government programmes may be sufficient to reach most girls in risk settings, a substantial proportion of the girls remain at risk of early marriage and school drop-out, and thus require targeted programming. Multiple forms of clustered disadvantage among hardest to reach is seen as key to ensuring India and achieves its gender, health and education SDG aspirations. |

|

2. ***** |

Phillips-Howard P, Nyothach E, Kuile FO, et al. (2016). Menstrual cups and sanitary pads to reduce school attrition, and sexually transmitted and reproductive tract infections: a cluster randomised controlled feasibility study in rural Western Kenya. |

Three-arm, open-label, cluster randomised controlled feasibility study in 30 primary schools in a rural area under a continuous Health and Demographic Surveillance System HDSS, Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) in Gem District in Siaya County, Western Kenya. |

Schoolgirls 14–16 yrs with no precluding disability, who were not pregnant, had experienced at least three menses, and were resident in the study area. A sample size of 185 girls per arm were selected from a population of 3165 girls. Interventions included training of health workers and school staff with participants in each arm receiving puberty and hygiene training; and menstrual products from 15 August 2012 to 27 August 2013 and followed until 21 November 2013. |

Primary outcomes were school dropout, defined as non-attendance for one term with no return to school; and days’ absence, defined as self-reported days absent per 100 schooldays. Secondary outcomes included the prevalence of confirmed STIs (vaginalis, trachomatis, and gonorrhoeae) and RTIs (bacterial vaginosis and albicans) during the end line survey. Safety outcomes were the incidence of TSS among girls provided with menstrual cups, and the prevalence of vaginal aureus. |

The cumulative risk of dropout by the end of follow- up was 11.2%, 10.2%, and 8.0% in the cups, pads, and control arms, respectively, and was mainly pregnancy related and did not differ significantly by arms overall or duration. Self-reported school absence was very rarely reported (0.4 [2.0] days per 100 of all [menstruating] school days) precluding analysis. Prevalence of all STIs at end line was 7.7% in the control arm vs 4.3% in the pooled cups+pads arms, 4.2% in the cups arm and 4.5% in the pads arm. The prevalence of RTIs (bacterial vaginosis or albicans) was 21.5%, 28.7% and 26.9% among cup, pad and controls arms, respectively (figure 2). Bacterial vaginosis comprised 71% of RTIs and was prevalent at 20.5% in the control arm. Recommendations include that future menstrual cup programs in schools ensure high- quality training on hygiene, and liaise with schools to advise on adequate school WASH facilities. |

|

3. ** |

Karaman 0. (2022). An Experimental Study Related to School Adjustment of Children in the Preschool Period. |

Semi-Experimental study design with 66.7% of students in a placebo group and 61.5% in a control group conducted in 3 state and 5 private preschools in Malatya Provincial Directorate of National Education, Turkey. |

53 students with aged 60-72 months with frequent school absenteeism due to a variety of Reasons, with a DAP (Designed Adjustment Program) protocol covering 8-12 days of interventions assessed in 2021. |

Measure the impact of the DAP protocol on preschool children not adjusting to school at the start of first schooling. |

66.7% of students (placebo group) and 61.5% of Students (control group) adjusted to school. Parental training provided positive results, with individual studies actively including parents, school and teachers found to be more effective. While peer acceptance was important for adjustment to school, there was a need to use social skill acquirements, with girls more successful at adjustment to school compared to boys. |

|

4. **** |

Kilburn K, Handa S, Angeles G, et al. (2017). Short- term impacts of an unconditional cash transfer program on child schooling: Experimental evidence from Malawi. |

Differences-in-Differences (DD) study model, which uses pre- and post-secondary data collected from an impact evaluation of Malawi's Social Cash Transfer Program (SCTP) which uses a well- implemented RCT that includes both quantitative and qualitative components. The quantitative data comes from a household survey, examining household composition, consumption, economic activity, education, and health and other factors to account for group-level differences across two study arms and across time. |

Study conducted from one-year impact from June-2013 (Baseline) across 1678 Cash transfer intervention households and 1853 delayed entry households (control group) Total 3531 households from 3 Traditional Authorities. |

Primary outcomes include school enrollments, temporary withdrawal and drop-out of children 6-17 yrs, with all measures being self-reported. |

The SCT program has a strongly significant effect on school enrolment and drop-out with children in intervention HHs 12% more likely to be enrolled and 4% less likely to drop-out with strong enrolment evident by all sub-groups. Findings provide strong evidence that the Malawi cash transfer program provides improved educational outcomes for children in the intervention homes, while the program increasing the likelihood of household expenditure on child education and clothing. Investment in education spending being the only mediator of school enrolment and drop-out. As such the Malawi SCTP is an effective demand side intervention which allows the poorest children to attend school by alleviating the financial burden on the household. Result identifies that unconditional CTPs to promote child development by targeting household poverty can improve child schooling outcomes in a relatively short period of time. Policy makers need to be conscious of these approaches to meet development goals and increase demand for education. |

|

5. *** |

Mason M, Galloway D. (2020). Knowledge mobilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: an impact evaluation of CPDL in improving primary school children’s performance |

A quasi-experimental pre- post intervention research design for an impact evaluation of children’s attendance and literacy for continuing professional development and learning (CPDL). Five interventions schools participated and were compared with ten control schools in Siera Leone, West Africa. |

Interventions for teacher training workshops and pedagogy (approx. 2 weeks and continued support for 1 year) and delivery to students of CPD in the intervention schools. A total of 51 teachers and 1,990 students involved, with 2,943 students in ten M1 and M2 control schools combined. Intervention year not identified. |

To assess the impact of a structured workshop-based programme of CPDL based on a Theory of Action, progressing from mobilising action in the NGO’s schools to improvements in teaching in the target schools and finally to improvement in student outcomes including attendance and their performance on a literacy test. |

Children’s attendance in experimental schools improved over that in the control schools. Performance in literacy also improved significantly and was maintained at follow-up. Attendance of intervention schools vs control schools was consistent with the widespread practice of starting school two or even three weeks after the official government opening date. The mean attendance for intervention schools improved by 23.8%, while control sites saw an improvement of 8.49% and a small drop of 2.51%. All the intervention schools improved attendance ranging from 15.1% to 30.12%. Recommendations to claim a causal relationship between the CPDL and improvement in children’s attendance and literacy, may require RCT methods with much larger samples although the use of change scores in analysis of these data is considered controversial. |

|

6. ***** |

KangwanaI B, Austrian K, Soler- Hampejsek E, et al. (2022). Impacts of multisectoral cash plus programs after four years in an urban informal settlement: Adolescent Girls Initiative-Kenya (AGI-K) randomized trial. |

longitudinal randomized trial exploring interventions including community dialogues on unequal gender norms and their consequences (violence prevention), conditional cash transfers (education), health and life skills training (health), and financial literacy training and savings activities (wealth). Participants were randomized to one of four study arms: 1) violence prevention only (V-only); 2) V-only and education (VE); 3) VE and health (VEH); or 4) all four interventions (VEHW). ANCOVA used to estimate intent-to-treat (ITT0). |

2,075 girls 11–14 years old living in an informal settlement (Kibera) in Kenya from 2015 to 2019. |

Theory of Change (TOC) based on a combination of an asset-building — that posits that girls need a combination of education, social, health, and economic assets to make a safe, healthy, and productive transition from childhood into young adulthood. The trial measured the impact of the AGI-K interventions. |

92.5% received at least one cash transfer with 9.5% receiving a mean of 12 cash transfers. 80.1% attended at least 12 group meetings, and 80.7% attended at least 4 financial education sessions, with 78.7 % receiving both annual savings incentives. Lower fertility outcomes reported due to delayed sexual debut with significantly lower HSV-2 prevalence and incidence in that study arm. Most girls were knowledgeable about modern contraceptive methods however limitations on contraceptive use due to girls’ inability to negotiate condom use, unplanned sex, fear of experiencing side effects, or wanting to become pregnant. Positive effects observed in the education outcomes summary index when compared to the V-only study arm. School enrollment already found to be high for this age group, likely explaining why there was only minimal impact observed for the other quantitative education indicators such as enrollment. For the older subsample there were also larger and significant reductions in the percent ever having had sex in the VE arm, while effects for ever having given birth in the VE and VEHW study arms were significant at 10% and a nearly 0.1 SD reduction in the fertility outcomes summary measure for the VEHW study arm, significant only at 10%. TOC identified potential intermediate benefits from interventions on household norms and economic assets, and on adolescent female educational, health, social, and economic assets. Multisectoral “cash plus interventions”, combined with education, health, and wealth-creation interventions that directly target girls in early adolescence, provide protection against early pregnancy and potentially have beneficial impacts on the longer-term health and economic outcomes of girls residing in impoverished settings. |

|

7. *** |

Sampa M, Jacobs C, Musonda P. (2018). Effect of Cash Transfer on School Dropout Rates using Longitudinal Data Modelling: A Randomized Trial of Research Initiative to Support the Empowerment of girls (RISE) in Zambia |

A cluster randomized trial (secondary data) conducted in Central and Southern provinces of Zambia. A Random intercepts model was used to model the individual effects estimates, taking account of the dependency likely to occur due to the repeated measurements and clustering in the study. RISE has a control arm and two intervention arms - material and economic support and combined intervention arm respectively. The randomization units (clusters) were basic schools and their surrounding communities. |

A total of 3500 adolescent girls in Southern Zambian schools were included in the study, including those who were married or cohabiting and girls who had given birth or receiving cash transfers. |

The study was to assess the effects of cash transfers on adolescent girls’ school dropout rates and other factors in the selected provinces of Zambia. primary Outcome variables was school dropouts with Independent variables of cash transfer, girls’ age (yrs), married / cohabiting, ever given birth, been pregnant, sharing of cash transfer, or living with her biological parents, |

Marriage or cohabiting and giving birth whilst in school were found to reduce chances of the girl continuing schooling. No significant association were attributed to the type of intervention; However, consistent receipt of cash transfers was shown to be a protective factor of school dropout rates in the study. Receiving cash transfers, a girl living with biological parents, ever given birth, being married/cohabiting and age of the adolescents found to be associated with school dropout while there was no evidence of an association with school drop out for girls sharing the cash transfers or the two intervention arms. Consistently receiving cash transfers are shown to be a protective factor of school dropout rates while early marriages and adolescent pregnancies are factors negatively affecting schooling. Recommendations are to keep girls in school to avoid indulging in illicit behaviour which could lead to early marriages and early pregnancies and subsequent school drop-out. |

|

8.**** |

Seidenfeld D, Prencipe L, Handa S. (2015). The Impact of an Unconditional Cash Transfer on Early Child Development: The Zambia Child Grant Program |

RCT longitudinal study with treatment and control groups of 2,515 households to investigate the impact of the child UCT grant program on a range of protective and productive outcomes. Study conducted in Kaputa, Northern Province; and Shongombo and Kalabo, Western Province; near the Zambian border. |

2,514 households, with 14,565 people, almost all of whom live below the extreme poverty line (95%) with almost one-third (4,793) of the sample being children under 5yrs, with the largest number under 1 year old (1,427). Two years of program interventions assessed from Oct 2010-Oct 12. |

Estimate effects of the UCTP on early childhood development (ECD) outcomes. |

Households who already own at least 1 book end up using the transfer to purchase more books, which leads to improved learning outcomes - on average, three more years of child schooling. UCT households have nearly .5 more activities attributable to the program than non-UCT households with impact driven by large households, as well as for male children. If cash transfers can improve early childhood development, then the benefits of UCTs extend well beyond the period of receiving cash, making the program much more valuable than initially estimated. |

|

9.** |

Amora YB, Dowden J, Borh KJ, et al. (2020). The chronic absenteeism assessment project: Using biometrics to evaluate the magnitude of and reasons for student chronic absenteeism in rural India. |

Chronic Absenteeism Assessment Project (CAAP), measured student attendance using a fingerprint scanner attached to a tablet biometric attendance system paired with home visits. Attendance data were aggregated by a

tracking software and used by “Education Extension Workers” (EEWs) who intervened promptly with chronically absent students at home. |

Conducted in ten schools over a seven-month period with students in grades 6 through 10. Students in ten schools in rural Telangana state of India |

The magnitude and causes of chronic absenteeism and to assess if the biometric system paired with home visits has the potential to decrease absenteeism. |

75.4 % of students missed 10 % or more of all school days and 56.2 % missed 15 % or more. Common reasons for absence reported by students were illness, menstruation, going to family functions, and a death/illness in the family. Being female and of higher social standing were protective factors against chronic. Authors noted the biometric system paired with home visits shows potential to decrease absenteeism. |

|

10. *** |

Cerutti P, Crivellaro E, Reyes G. et al. (2019). Hit and Run? Income Shocks and School Dropouts in Latin America. |

Secondary longitudinal data from the Labour Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (LABLAC) for Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, students exiting upper secondary and tertiary education in Argentina and Brazil, but not in Mexico. |

Youth and young adults aged 15–25 yrs (more than 160K participants) analysing data from 2005 to 2015. |

The impact of a negative household income shock on the enrollment status of the young.

. |

Findings suggest that negative income shocks significantly increase the relative risk of students exiting upper secondary and tertiary education in Argentina and Brazil, but not in Mexico. Evidence that youth who exit school due to a household income shock have worse employment outcomes than similar youth who exit without a household income shock. Differences in labour markets and safety net programs likely play an important role in the decision to exit school as well as the employment outcomes of those who exit school. Authors point to policy implications and directions for social safety nets or expanded access to educational credit lines that act as insurance mechanisms to play an important role in reducing the adverse effects of shocks on household income and support increases in skilled labour. |

Meta-analysis assessment

Of the 21 studies included in the review, those that investigated the impact of cash transfers on various outcomes and or contained several parameters of interest relating to school completion/dropout were identified as having the best opportunities for meta-analyses. These nine (n=9) studies are listed as #4, 6, 7, 8, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21 in Table 2. However, following further review, a meta-analysis was deemed inadequate due to significant heterogeneity in study designs, reported outcomes, and data availability. Specifically, one study lacked estimable effect sizes, and two studies reported only regression coefficients without raw data. Additionally, two studies examined attendance within intervention sessions, diverging from the review’s focus. While three studies reported some relevant outcomes, this limited sample size (of estimates available in these studies) will render pooling of the data statistically which makes them insufficient for a meaningful metaanalysis.

Table 2: Evaluation Designs/Longitudinal Studies/Time-Series Analysis and Mixed Methods (n=10 studies)

|

11. ** |

Grepon BG, Cepada CM. (2021). Absenteeism and parental involvement in home and school among middle school students of public school in northern Mindanao, Philippines: basis for intervention. |

Descriptive–correlational eval. method used with, frequency, weighted mean, Pearson R Pearson R correlation, and t-test for Two Independent Means. |

60 Middle school students at a public school in the Philippines. |

Determine the extent of absenteeism, extent of parental involvement and respondent’ perceptions towards parental involvement. Correlates of students’ absenteeism and parental involvement both at home and school. |

Parents were greatly involved at home but were moderately involved in school which contributed to the absenteeism of the students. Parental involvement in school was deemed important in terms of giving support and monitoring their children’s attendance and performance in school. Parental involvement in school had a strong negative relationship with absenteeism - Parental involvement decreased, absenteeism among students with a significant relationship between parental involvement and absenteeism, both at home and in school. |

|

12. * |

Zulaika G, Bulbarelli M, Nyothach E, et al. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on adolescent pregnancy and school dropout among secondary schoolgirls in Kenya. |

Longitudinal study using a causal-comparative design conducted in rural western Kenya |

910 secondary school girls in 12 secondary day schools between 2018 and 2021. 403 girls who graduated after completing their final school exams in Nov. 2019 (pre- pandemic) with 507 girls who experienced disrupted schooling due to COVID-19 and sat exams in March 2021. |

Adolescent pregnancy and school dropout due to COVID-19. |

Girls experiencing COVID-19 containment had twice the risk of falling pregnant prior to completing secondary school after adjustment for age, household wealth and orphanhood status (aRR)=2.11; 95% CI:1.13 to 3.95, p=0.019); three times the risk of school dropout (aRR=3.03; 95% CI: 1.55 to 5.95, p=0.001) and 3.4 times the risk of school transfer prior to examinations (aRR=3.39; 95% CI: 1.70 to 6.77, p=0.001) relative to pre-COVID levels. Recommendations include appropriate programs/ interventions to buffer the effects of population-level emergencies on school-going adolescents. |

|

13. ** |

Aygün AH, K?rdar MG, Koyuncu M, et al. (2024). Keeping refugee children in school and out of work: Evidence from the world's largest humanitarian cash transfer program. |

Evaluative/Comparative study using dependency- ratio cutoff in a regression discontinuity design based on WFPs Comprehensive Vulnerability Monitoring Exercise (CVME) in Turkey to assess vulnerability of refugees and their children by household demographics, arrival profile, housing, income sources, consumption expenditures, food security and coping mechanisms, and health and special needs. Propensity score matching (PSM) used to assess beneficiary households to non-beneficiary applicants including child labour and school enrollments. |

Refugee beneficiary households and their children of Unconditional Cash Transfers (UCTs) against households that do not receive UCTs conducted in 2023. |

Investigates if UCTs can lower the incidence of child labour and raise school enrollment among refugee children in Turkey. |

Being a UCT beneficiary household reduces the % of children working from 14.0% to 1.6% (-88%) and the % of children aged 6–17 not in school from 36.2 to 13.7% (- 62%). Effects on child labour and schooling are larger among lower-income households, indicating that it is these children who benefit most from UCTs. |

|

14. *** |

Dustan A. (2019). Can large, untargeted conditional cash transfers increase urban high school graduation rates? Evidence from Mexico City's Prepa Sí. |

Cross sectional empirical study from four data sources using difference-in- discontinuities comparing eligible and ineligible students within the same high school. |

Students within Prepa Sí cohorts from 2005- 2008 in 10th grade. Study conducted in 2008 in Mexico City urban environs. |

To estimate the effect of Prepa Sí CCT program eligibility on the probability of completing high school. |

No appreciable effect on high school completion due to the CCT program identified with results sufficiently precise to rule out policy-relevant effect sizes. Null effects persisted for subgroups that could be candidates for a targeted program, with end-of-high school exam scores unaffected by the program with effects on high school choices by eligible students being minimal. Findings suggest that liquidity constraints are not a key driver of high school dropout in this urban setting with results highlighting the challenges of using cash to improve academic outcomes in cities. |

|

15. *** |

Setyadharma A. (2018). Government’s Cash Transfers and School Dropout in Rural Areas. |

Evaluation study of primary data was collected from rural areas in all regencies and cities in Central Java, Indonesia. The likelihood to drop out is estimated using Probit regressions. |

229 former upper secondary school students and 458 parents/guardians living in rural areas, regencies and cities in Central Java Province, Indonesia with the study conducted in 2017-18. |

Exploring of comparators of Cash transfers, Socio-demographic, household and school variables. |

Significant findings by perception of education (-3.32***), examination grade (High -2.06***), changing school since primary (0.57**), Deviant behaviours (1.18***), Household head with university education (-2.35**), Father/male guardian academic support (0.11*), Nonworking mother (-2.74***). Number of siblings dropping out (1.15***), Helping family with daily business/work (-1.14**), Father’s participation in household decision making (-0.11***), School’s curriculum: Vocational vs Madrasah (Islamic Religious School) (0.93*), Teachers’ quality (-1.02**), Unemployment rate (-0.42***) and receiving student government cash transfer (-1.96***). Recommendations for the Gov. to reduce education costs and expand the number of cash transfers for poor rural students. |

|

16. ** |

Santos FM, Corseuil CHL. (2022). The effect of Bolsa Familia Program (PFB) on mitigating adolescent school dropouts due to maternity: An area analysis. |

Empirical evaluation of individual and area level secondary data from the Brazilian Census (2010) examining households with per capita income of R$500 or less, and where there was at least one adolescent female. inhabitant aged between 12 and 19 yrs. Logit regression to explore variables related to the PFB. |

Adolescent mothers and non-mothers between 12-19 yrs in low-income families in Brazil with analysis conducted in 2021. |

PFB variables explored including policies and Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) associated with school attendance in low-income families and are more intense with adolescent mother’s vs non mothers. |

Motherhood negatively correlated to schooling of adolescent mothers. Negative correlations found by age 12-15 yrs, living with parents, and mothers living at home while positive correlations by urban locations, head of households schooling, and having a spouse. The higher the impact of PFB the relatively lower attendance of school of young mother’s vs non-mothers. Findings reinforce the importance of policies to ensure the retention of adolescents in school during and after pregnancy. Recommendations include day-care support for young mothers in schools due to the limited impact of CCTs on this cohort. |

|

17. ** |

Smith WC. (2022). Consequences of school closure on access to education: Lessons from the 2013–2016 Ebola pandemic. |

Secondary data analysis using USAID DHS and UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey from before and after the 2013–2016 Ebola pandemic in Guinea and Sierra Leone in West Africa. Descriptive and inferential statistics to explore variables related to school attendance and closures. |

Secondary-school age youth from schools in Guinea and Sierra Leone in West Africa with analysis conducted in 2020. |

The extent of school disruptions during the Ebola pandemic in Guinea and Sierra Leone the pattern for enrolment among school age Youth and the extent, that the alterations affected marginalised groups. |

School disruptions including pandemic threat can have a negative impact on educational outcomes, and those impacts can be highest among most marginalised youth. Post-epidemic youth in the poorest households saw the largest increase in school dropout. An additional 17,400 of the poorest secondary age children were out of school than prior to the epidemic. Using schools as treatment centres, led to hesitation among families for their children to return to school. Recommendations that it’s important to minimise the likely post-epidemic expansion in inequality. Author’s findings point to the need for sustainable planning that looks beyond the reopening of educational institutions including comprehensive financial support packages for groups most likely to be affected. |

|

18. ** |

Nedungadi P, Mulki K, Raman R. (2016). Improving educational outcomes & reducing absenteeism at remote villages with mobile technology and WhatsAPP: Findings from rural India. |

Netnographic approaches where 8968 chats from the target population were coded and analysed using WhatsApp chats and AmritaRITE monitoring apps, along with GPS data for location. |

54 educational village centers, in India actively using this methodology, though the data used is for 18 centers in Uttarakhand villages with 19 teachers, 5 cluster coordinators 2 central coordinators in the villages using mobile technology across 9 months. |

To identify if using online apps to monitor, support teachers and monitor active engagement of community by the teachers helped attendance and or performance on both teachers and students. |

Of the 8968 total chats, 22% (n = 1932) provided guidance, motivation, assistance, pedagogical content, and problem resolution, suggesting that the AmritaRITE environment is conducive to promote a positive and supportive environment. Training and building a process for teacher monitoring and accountability has resulted in better attendance of both teachers and students and more streamlined and predictable execution of planned activities. Recommendations include a shift to realign the University calendars and that of basic schools to reduce teacher loss from 9 weeks to 6, increase practical approaches and decrease theory content, and adequate feedback be given to teachers attending courses prior to examination, to spur them on to learn and perform well. |

|

19. ** |

Kipchumba E,

Sulaiman M. (2017). Making schools more girl friendly: exploring the effects of ‘girl friendly space’ on school attendance of adolescent girls. |

Exploratory study analysis of secondary data and qualitative findings from students in Somalia. Random sample of students, grades 4-8 drawn from their respective class registers. In each grade, an equal number of girls (4) and boys (4) were sampled: Total 933 students including 470 boys and 463 girls conducted in schools in Somalia. Comparisons between 3 GFS schools and non-GFS schools conducted. |

Male and Female Somali students in grades 4-8 across in 24 schools, across four districts of Somalia during February-May 2017. |

Understand the potential impact of GFS on girl’s school attendance. |

GFS dropout rate for girls 7% while non-GFS school drop-out was 12% (2016). Poor hygiene facilities can cause both low attendance and higher dropout. Significantly larger proportion of GFS schools were living with both of their biological parents. No significant differences observed in having a male member as household head or girls’ distance from schools. Students from GFS schools have 11% lower absenteeism for both boys (37% vs. 26%) and non-adolescent girls (38% vs. 27%), with the difference much sharper at 19% for adolescent girls (33% vs. 14%). Girls in GFS schools also far less likely to report sickness related absence compared to their counterparts in schools without GFS (22% vs 15%) vs only 5% difference for boys. Recommendations - Results are indicative of GFS as a possible tool on increasing girl’s school attendance, proper impact evaluation is required to estimate the full effects of GFS as an intervention. |

|

20. ** |

Kookana RS, Maheshwari B, Dillon P, et al. (2016). Groundwater scarcity impact on inclusiveness and women empowerment: Insights from school absenteeism of female students in two watersheds in India |

Secondary data from responses gathered via a socio-economic survey involving 500 families in the study area were used in the study Eight secondary schools located in two watersheds in Gujarat and Rajasthan (semi-arid region of India). Survey responses to a detailed questionnaire by a cohort of students in both watersheds; and school attendance records. |

500 families with Yr 8 class students (13–14 yrs old) in both watersheds with data collected in academic years 2010–2013). |

Assess student perceptions on groundwater scarcity issues and the impact of water scarcity on their educational opportunities. |

79% of students were satisfied with school sanitation while 84% of households do not have sanitation facilities. 79% of students in Gujarat and 92% in Rajasthan, education was identified as very important while <10% found it somewhat important. In Gujarat, 59% of students identified less water available than needed in their village with Rajasthan reporting 61%, including 16% of the students identifying a serious lack of water. 68% of students in Gujarat arrived late or left school early due to household duties, while 65% of students missed school altogether while 24% of Rajasthan students reported missing school up to 2 days a month and about 13% up to 4 days per month. on average there were more female students absent in each month compared to males. Recommendations are that groundwater scarcity contributes to school absenteeism with girls affected the most, with this issue limiting women’s empowerment. Therefore, any policy changes or initiatives to improve inclusive educational opportunities and empowerment need to consider water availability. |

|

21. ** |

Hunsaker S. (2018). Reducing the constraints to school access and progress: assessing the effects of a school scholarship program in Malawi. |

Causal-comparative research design comparing intervention (scholarship) and control (those not received) the needs-based scholarship to attend secondary or tertiary school). Face to face interviews with standardised survey design using the Tanzanian Standard Class. of Occupations. Random selection and convenience sample of students currently in school And those who had graduated. |

Surveys administered to 89 scholarship recipients and 57 non recipients in the Dowa, Kasungu and Lilongwe Districts of Malawi. Survey conducted in 2018. |

Explore the educational experiences and outcomes of the two student groups. |

Those that received the scholarship graduated at an average rate of 97% across secondary and tertiary schooling, while non-recipients graduated at an average of 19% for tertiary school and 50% for secondary school. Overall, scholarship recipients are more likely to attend because the scholarship which covered boarding school and in turn made them less likely to withdraw. Recipients also received jobs at higher rates; however, the quality of that work is not significant between recipients and non-recipients. Overall, the scholarship program had positive significant effects on many of the desired outcomes. |

Summary of key findings

Of note from the search of electronic databases was the fact that social and behaviour change (SBC) was rarely if ever mentioned in intervention approaches, despite a number of SBC activities being highlighted in programs targeting OOSC including, training and capacity building, identification of key influences of teachers, parents and peers, the development of purposive training interventions, structured syllabus, and the targeting of a number of participants from the education supply and demand sides. (Mason M, Galloway D.; 2020). Additionally, SBC messages to achieve desired program outcomes, and support policy initiatives to incentivise or “Nudge”[17], vulnerable groups toward greater engagement and retention in schools were also highlighted (Santos FM, Corseuil CHL; 2022; Nedungadi P, Mulki K, Raman R.; 2016).

Facilitators or enablers toward improved engagement and student retention in schools included a number of approaches. Multipronged and multisectoral approaches were highlighted as having greater opportunities for positive change over singularly pronged initiatives. These included other SBC activities such as teacher training and capacity building, and the use of Interventions that involved parents as well as students (Grepon BG, Cepada CM.; 2021). Other incentives to improve student retention for vulnerable groups of pregnant and lactating mothers included recommendations for day-care support in schools where CCTPs may not have significant impact to retention on some cohorts (Santos FM, Corseuil CHL.; 2022). Furthermore, implementation of Girl Friendly School (GFS) policies and programs were also identified as reducing the levels of absenteeism and school drop-out amongst highly vulnerable girls, although the authors noted more studies on approaches and efficacy of these approaches may be needed (Kipchumba E, Sulaiman M.; 2017).

Other gender focussed incentives to increase retention and reduce drop-out included the availability of sanitary products (Phillips-Howard P, Nyothach E, Kuile FO, et al.; 2016) although, adequate training was recommended and needed to be provided with the availability of a range of products. Other perspectives from the demand side identified that capacity building of parents through engagement and training was also found to provide positive results, as well as actively including parents and teachers in schools to address absenteeism and drop-out, in particular with problem children (Karaman 0.; 2022).

Unconditional and Conditional Cash Transfer programs (UCTPs/CCTPs) featured prominently with studies, with eight (n=8) UCTPs/CCTP studies identified which matched the search criteria, with findings found to have generally demonstrated positive impacts on student retention and reduced drop-outs (KangwanaI B, Austrian K, SolerHampejsek E, et al.; 2022; Setyadharma A.; 2018; Kilburn K, Handa S, Angeles G, et al.; 2017), and this includes retention of vulnerable groups (Sampa M, Jacobs C, Musonda P.; 2018) and very young children in households receiving the benefits (Seidenfeld D, Prencipe L, Handa S.; 2015). However, the impact of cash transfers on student retention may be limited in hard-to-reach vulnerable groups residing in remote rural areas (Prakash R, Beattie TS, Javalkar P, et al.; 2019).

Additionally, income shocks were found to be a significant predictor of school continuity (Cerutti P, Crivellaro E, Reyes G. et al. (2019) suggesting that CCTPs may positively impact on school retention. However, the findings on CCTPs/UCTPs are also mixed with indications that liquidity constraints may not be key driver of high school dropout in some urban settings (Dustan A.; 2019) while other studies identify socio-cultural factors including suspicions and negative perceptions of schemes that are perceived as equitable (Banda E, Svanemyr J, Sandøy IF, et al.; 2019). A number of barriers to school engagement and student retention were identified through the review. Environmental factors such as sanitation and water scarcity in dry regions have been identified as contributing to school absenteeism with girls affected the most (Kookana RS, Maheshwari B, Dillon P, et al.; 2016), while poverty, geographic locations, including distances to schools, teacher quality, the lack of material resources and emotional support, physical and sexual abuse, early pregnancy and poor perceptions of the benefits of schooling were also cited as barriers to reducing OOSC rates in a number of studies (Mason M, Galloway D.; 2020; Sandøy IF, et al.; 2019).

Prospects were also identified for existing young adult school dropouts to renew their study through selfdirected home learning (Musita R, Ogange BO, Lugendo D.; 2019) although practical approaches to re-entry of previous dropouts to secondary schools may need to be considered through specifically designed low-cost courses. Scholarship programs were also found to have positive impacts on school retention and completion especially when they cover boarding school fees (Hunsaker S.; 2018). However, scholarships may also foster resentment from other students or face considerable resource constraints for replication at scale. A number of other approaches were also identified from the studies selected in supporting longer term school retention of primary and secondary school students. The use of digital technologies and mobile apps were found to enhance the learning process for teachers and students and reduce levels of drop-out or improve re-entry of students through novel approaches. (Nedungadi P, Mulki K, Raman R.; 2016; Musita R, Ogange BO, Lugendo D.; 2018).

Learnings from the recent COVID-19 pandemic has also led to recommendations that long-term considerations should include sustainable planning that looks beyond the reopening of educational institutions including comprehensive financial support packages for groups most likely to be affected by pandemic threats and other school disruptions as these can have a negative impact on educational outcomes, with those impacts being highest among most vulnerable youth (Smith WC.; 2022; Zulaika G, Bulbarelli M, Nyothach E, et al.; 2022).

Risk of bias assessment

Figure 1 provides assessment of potential biases in multiple Cluster RCTs including in this systematic review. The assessment of bias in the RCTs cluster included in this systematic review revealed varying levels of concern across different domains. Several studies, such as those by Prakash et al., Kilburn et al., and Seidenfeld et al., demonstrated a low risk of bias across most domains, indicating a robust methodological approach. In contrast, studies like Karaman et al. and Amora et al. were identified with a high overall risk of bias, primarily due to concerns in critical areas such as randomization and blinding procedures. Other studies, including Philips-Howard et al., Mason et al., Kangwana et al., and Sampa et al., exhibited some concerns in multiple domains, suggesting potential limitations in study design that may influence the reliability of their findings. Overall, the risk of bias assessment indicates a heterogeneous quality of studies, with a mix of low-risk and high-risk biases (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Risk of Bias Assessment for Article Domains D1-D5.

The assessment of bias in the observational studies of exposure included in this systematic review highlights a spectrum of methodological quality across the studies (Figure 2). Several studies, such as Grepon et al., Cerruti et al., Santos et al., Smith et al., and Hunasker et al., were identified as having a high overall risk of bias. These studies exhibited consistent concerns across multiple domains, particularly in randomization (D1), measurement of outcomes (D4), and overall assessment (D7), which may affect the reliability of their findings. Conversely, studies like Zulaika et al., and Aygun et al., demonstrated a low overall risk of bias, with minimal concerns noted in most domains, suggesting a more robust methodological approach. However, a number of studies, including Dustan A., Setyadharma et al., Nedungadi et al., Kipchumba et al., and Kookana et al., were found to have some concerns overall, indicating potential limitations that could introduce bias into their findings (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Risk of Bias Assessment for Article Domains D1-D7

DISCUSSION

The synthesis of findings from this systematic review identified that SBC is currently not part of the lexicon for educational policy making or interventions. This highlights the importance of greater integration of SBC approaches within the educational sector to address OOSC challenges in LMIC contexts. As such, there is a need to strengthen the discussion on the theoretical underpinnings of SBC and how it could be better integrated into educational interventions which to date, are not evident in the international literature, despite SBC demonstrating successes in other child health and welfare issues [18,19]. The review findings also point to the fact that the greatest benefits may be achieved through SBC targeted interventions to high-risk groups including low-income, rural populations, girls, and previous school drop-outs, with these findings reflecting previous research in the area [1,2].

Furthermore, the synthesis of findings indicates that solutions to the problems of OOSC are complex and will not be achieved through singularly focussed programs and activities, but rather through the adoption of more strategic approaches. In the first instance, this may require a more comprehensive understanding of the scope of the problems as well as greater understanding of the current programs, practices, and resources targeted to addressing the problems. Also identified was the importance of developing community-driven plans to address school dropout including interventions that accept community resource opportunities and limitations. Last, evident from the large scale RCTs and longitudinal studies, was the need to continue with ongoing assessment, including monitoring, evaluation, learning and adaptation (MELA) for SBC activities to ensure that community initiatives have the desired behavioural impact. Paying greater attention to warning signs of dropout problems, getting a deeper understanding of which students are most likely to drop out, and identifying the early-warning signs to alert teachers, school staff, and parents to the need for intervention were factors highlighted for consideration prior to the development of community led interventions.

Of the findings in relation to the eight (n=8) UCTP/ CCTP studies, it is apparent, given the weak to moderate evidence of success, that more strategic implementation and promotion of CTPs should be considered. Despite the mixed findings of this review, metanalyses conducted of CCTPs, have identified that they have demonstrated strong support for all schooling outcomes in impact, transfereffectiveness, and cost-effectiveness estimates for LMIC contexts at a global level [20]. This may incorporate a more family/student-centred funding model, given the understanding that it will cost more to educate vulnerable students, including those living in poverty, those living with disabilities, or facing rural disadvantage or gender inequalities. This also recognises the need for a cash transfer funding model in areas of need, to be adjusted to a funding allocation based on the socio-demographics of individual students, their schools and communities, which more closely aligns funding to specific student needs. CCTPs which included food supplementation within school settings was a feature of school programs in Southern Asia, although, it was not evident in the African region.

School meals programs have been found to “NUDGE” students to attend school as well as providing incentives for parents to send their children to school [21,22]. Although, initially funded by international donors such as the World Food Programme (WFP), transitioning toward full Government ownership and implementation has provided these programs with a level of sustainability. The programs can have 3-fold benefits in disadvantaged rural areas including increased attendance, retention and primary school completion, improved consumption of nutrient-dense foods with high-risk children; and increased market participation of smallholder farmers through the provision of quality and diversified products [16,17]. Regulations and policy, including policies for Universal Primary Education (1977) and Fee-Free Basic Education (FFBE; 2016) can also have significant impact on school engagement and retention of vulnerable students. Although, this issue was not included in the literature review inclusion criteria, with policy approaches and appropriate laws being reviewed in the African context and seen as important to maintain school attendance and manage learner absenteeism [23]. Stigma and discrimination emanating from student low socio-economic status was also highlighted in numerous studies in the review.

However, the impact of free uniform programs on OOSC rates was not evident. Other studies have also emphasised a note of caution in considering the negative impact of approaches such as uniform programs designed to build retention and improve school performance with some students [24], with findings that they may also lead to increased drop-out with higher-risk groups if the programs are not implemented in an equitable manner, with barriers to engagement also reported in other studies with pregnant mothers (Santos FM, Corseuil CHL.; 2022). A number of review interventions focussed on capacity building of both education supply and demand-side participants, acknowledging the importance of cultivating relationships with teachers, trusted adults and peers, and the iterative nature of approaches [25], through advisory groups —small groups of students that come together with teachers to create an in-school family of sorts. These advisories, which meet during the school day, may provide a structured way of building skills and enabling those supporting relationships to grow and thrive.

Enhancing family/friend relationships has also been seen as a factor which may assist in providing a more protective environment, particularly for girl students, to reduce violence by teachers [8,9]. From the supply side of teachers and school administrators, findings indicate that a range of capacity building approaches may be required to ensure learning is relevant to the needs of students, as boredom and disengagement have been identified in the review as some of the reasons students stop attending class and drop-out of school, with these issues also evident in other literature on student engagement and retention [26]. From the demand side of problem students, personalising learning opportunities to create small learning communities, for groups with special needs was another strategy to reduce the dropout rate. In this regard, the review identified that the demands of working and/or family responsibilities make it untenable for high-risk students to attend school during traditional schedules with similar challenges to identifying flexible learning opportunities for working students [27]. This may require more flexible approaches to the school syllabus through the development of sandwich programs identified in the review as having mixed benefits as well as weekend or evening classes, to provide at-risk student flexibility in scheduling.

For vulnerable girls’, retention approaches could also include the greater provision of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) personal hygiene products and facilities as well as the eligibility or provision of subsidies for childcare, to allow girls and their partners to continue with their education [28]. The findings on the prospects of improved rigour within schools also indicate that raising the academic bar may reduce dropout rates through improved teacher, student engagement while supporting students desire to achieve higher levels of success, and also prepare them to graduate with improved options. This also reinforces the need to target interventions to teachers to build their skills and confidence in providing optimal teaching opportunities as well as reinforcing strict adherence of ethical conduct.

SBC Intervention outcomes

Systematic review findings against the six research questions are as follows:

RQ1: What SBC interventions have been the most successful in in low -and middle-income countries to reduce child and youth school drop-out, and improve retention and completion?

The evidence indicates that multipronged SBC approaches can be the most successful with activities that include capacity building and training of supply side actors—teachers, principals and school administrators— and demand side actors—students, parents, families, peers and other community influencers, combined with advocacy for policy initiatives to create educational environments which are “more conducive to student retention” through progressive and flexible syllabus, safe and stimulating learning environments with adequate WASH resources. A focus on this range of activities, may be the most effective combination of interventions to elicit social and behavioural change toward improved student uptake, retention and future educational outcomes. However, despite the evidence on the efficacy of a combination of interventions adopting both “global and targeted strategies” impact on OOSC in developing countries, scoping reviews recommend further research to be conducted in different countries to confirm the effectiveness of the range of interventions, given the differing cultural contexts [29].

RQ2: What are the determinants associated with the enrolment and retention of OOSC in primary and lower secondary school?

The predominant range of social and behavioural determinants identified from the review included socioeconomic, geographic and behavioural factors that influenced enrolment and retention of children in schools in LMICs. Income disparities which are higher in rural and remote rural communities require children to generate income for their families, rather than participate in school. Resource constraints including WASH resources are also a significant determinant with low-income groups and have a higher impact on girls than boys. From a behavioural perspective, poor attitudes and negative social norms of low-income rural parents and children, in relation to the quality of schooling or the longer-term benefits of education persist, particularly with higher-risk groups. In line with WASH initiatives, girl friendly schools (GFS) are seen as a possible tool to increase girl’s school attendance The studies confirm earlier studies in Tanzania and the East Africa region on the challenges to retention with specific at-risk groups [30].

RQ3: How do social/ cultural norms, attitudes, perceptions, and social structures impact school participation among primary and lower secondary schoolaged children?

Negative social norms toward education are often established because of the growing inequality and dispossession of vulnerable groups and are prominent in many rural and urban informal settlements in LMICs. Education is not yet established as a positive social norm in many communities and hence inadequate sanctions are attached to it. Feelings of hopelessness and helplessness may pervade in a number of communities with negative social norms toward education, with a variety of studies identifying lower levels of “perceived behavioural control” —poor attitudes and self-efficacy perceptions to affect positive change—with participants and community groups. As a result, greater engagement and support through SBC is required to build skills and confidence of community members with the understanding that early education of children is a basic human right that offers many longer-term benefits for families. Additionally, improving knowledge about sexual and reproductive health may reduce the high level of pregnancies identified in areas of disadvantage and improve retention rates of girl students [11].

RQ4: How effective are the existing policies and interventions in addressing the challenges faced by OOSC?

A range of policies and interventions following fee-free-basic-education (FFBE) have contributed to improving school attendance and completion. One of the primary areas of intervention to address school retention and engagement apparent in the review were evaluations of UCTPs and CCTPs with the programs generally demonstrating some improvements in school attendance and engagement. However, non-significant findings in differences between intervention and control groups also indicate that more culturally nuanced approaches to UCTPs/CCTPs may need to be piloted and carefully evaluated given the lack of achievement in intended results identified in some studies. This includes CTPs that provide NUDGES through nutrition components such as “home-based lunch provision”, that contrary to program objectives, contributed to increased absenteeism, lateness, transfers and attrition, thus reducing child retention capacity of schools [31].

Conversely, the inclusion of school food supplementation, as a component of CCTs may be more successful than UCTPs delivered at household level. Findings from other studies also indicate that CCTPs that include nutrition requirements may improve student biometric measures while improving child school attendance [32]. Given that income shocks were found to be a significant predictor of school continuity and retention, CTPs for families with children at high-risk should be considered through targeted interventions. Alternatively, CCTPs for families with school age children should include a condition that the benefits will only be provided following confirmation of regular attendance to schools, given that school retention is the objective.

RQ5: What are the key challenges and opportunities associated with alternative education models for OOSC?

The key challenges from a LMIC context relate to human and financial resource constraints to implement multipronged SBC approaches and trialling of alternative educational models and the considerable scale of the interventions required, given the considerable challenges. What is evident is that a number of alternative educational models identified from the international literature such as ODeL secondary school re-entry programs (Kenya), Girl Friendly Schools (Somalia), Continuing Professional Development and Learning (CPDL) capacity building approaches (Sierra Leone), Accountability Theory approaches to support orphaned children, and Sandwich Programs (South Africa), Designed Adjustment Programs (DAP) for Children in problem preschool children (Turkey), and the greater adoption of mobile technology in educational settings (India), need to be considered and co-designed with the communities facing the greatest challenges. Opportunities arise with more strategic planning and formative research in the early stages of SBC program development to support culturally relevant, alternative educational models that create greater engagement of local communities in the development of these models. This will ensure a buy-in and ownership of the education interventions to ensure sustainability in the longer term.

RQ6. Of the programs demonstrating positive outcomes how did their effectiveness vary by the type and scale of the interventions, and student sociodemographic and cultural backgrounds?

Learnings from the interventions and studies assessed through the review as well as evidence from earlier studies [33], identify the need for more systematic and strategic SBC approaches to build knowledge, change attitudes, perceptions and social norms toward the benefits of school learning environments for students and their families. The variable impact of some programs including cash transfers, educational models and programs to re-engage dropouts indicates that socio-economic, demographic and cultural factors, implementation approaches, the scale of the interventions and other factors have played a part in the success or otherwise of the interventions. As such, SBC can play a more significant role in developing more culturally nuanced, educational approaches, including the piloting, evaluation and scaling-up of successful approaches in the African context.

Limitations