Echocardiographic Characteristics of Cardiogenic Shock in the Cardiology Department of the Yalgado OUEDRAOGO University Hospital of Ouagadougou

- 1. Department of Cardiology, CHU Yalgado Ouédraogo, Burkina Faso

- 2. Department of Medicine, Ouahigouya Regional Hospital, Burkina Faso

Abstract

Echocardiographic data allow better management of cardiogenic shock and improved prognosis. The objectives of this study were to describe the etiologies of cardiogenic shock and their echocardiographic characteristics in the cardiac intensive care unit of the Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital.

Methods: This was a descriptive cross-sectional study over a 6-month period from April 1, 2019, to September 30, 2019, conducted at the cardiac intensive care unit of CHU Yalgado Ouédraogo. Patients admitted for shock were systematically performed a cardiac Doppler echo using a portable vivid Q ultrasound machine, equipped with a 2-4 Mhz probe.

Results: We collected 30 cases of shock, the most frequent being acute cardiac decompensation (63.33%), severe pulmonary embolism (20%) and acute coronary syndrome ST+ (10%). Cardiac echocardiography found valvular heart disease with cavitary dilatation and probably ischemic heart disease in five cases, respectively, and dilated cardiomyopathy and acute cor pulmonale in two cases, respectively. The mean LVEF was 38.56 ± 19.37% (extremes 5 and 72%). Mortality was 56.66%. In multivariate analysis, the independent predictor of death was LVEF less than 22% (OR = 37.13; CI95 [29.9-946.26], p=0.002).

Conclusion: The etiologies of cardiogenic shock states are dominated by acute decompensation of pre-existing heart disease, pulmonary embolism and ST+ acute coronary syndrome. Independent predictors of mortality were LVEF <18% ((OR =4.7; CI95 [1.25-9.23], p=0.0001)), dobutamine use ((OR =2.8; CI95 [1.05-6.93], p=0.001)), and mitral stenosis ((OR =10.5; CI95 [1.65-15.20], p=0.0001)).

Keywords

• Cardiogenic shock

• Echocardiographic features

• Mortality

• Burkina faso

Citation

Valentin YN, Justine KL, Salam O, Harouna K, Grégoire B, et al. Echocardiographic Characteristics of Cardiogenic Shock in the Cardiology Department of the Yalgado OUEDRAOGO University Hospital of Ouagadougou. J Cardiol Clin Res. 2021; 9(2): 1176.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiogenic shock is defined as the inability of the ventricular pump to generate sufficient blood flow to meet the metabolic needs of the peripheral organs [1,2]. It remains the most serious complication of various heart diseases. It affects about 7-10% of patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome in developed countries and is the leading cause of hospital mortality in this disease [3]. Indeed, mortality reaches 40-50% despite the optimization of revascularization procedures [4,5].

The etiologies of cardiogenic shock are numerous. In industrialized countries, acute coronary syndrome dominates, accounting for 70% [6]. In developing countries, there is little data available.

The hemodynamic instability of patients in shock limits their movement for imaging examinations in order to clarify the etiologies and improve management. Hence the importance of the practice of explorations at the patient’s bed, which is popularized in developed countries. It improves the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of these patients [7].

The objectives of this study were to describe the etiologiesof cardiogenic shock as well as their echocardiographic characteristics and to identify the predictive factors of death in the cardiac intensive care unit of the Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital.

METHODOLOGY

This was a prospective study over a six-month period from April 1, 2019, to September 30, 2019, conducted in the intensive care unit of the cardiology department of the CHU Yalgado Ouédraogo.

We systematically included cases of cardiogenic shock admitted to this unit. We defined cardiogenic shock as systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, with signs of hypoperfusion (pallor, skin mottling, coldness of the extremities, oliguria, or altered consciousness) associated with altered cardiac output on echocardiography.

In each patient, we performed a clinical examination, a biological workup including urea and creatinine, blood glucose, troponin I as appropriate, a blood count, a blood ionogram, AST/ALT, PT, and TSHus; an 18-lead surface ECG in search of a rhythm or conduction disorder; and transthoracic Doppler echocardiography using a VVDQ portable echocardiographer with a 2 to 6 MHZ probe to look for large pericardial effusion, disturbed segmental kinetics of both ventricles, PAH, severe valvulopathy, endocarditis, and altered LVEF and ESRD. All these examinations were repeated once a day during the patient’s stay in the intensive care unit.

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS software. Student’s t test and chi-2 test were statistically significant if P less than 0.05. Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to look for factors predictive of death.

RESULTS

Epidemiological Data

During the study period, 428 patients were hospitalized in the department, including 72 in the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU). Of these patients, 30 were in cardiogenic shock. Shock thus represented 7% of cardiology admissions and 41.67% of ICU admissions. The sex ratio was 1.14.

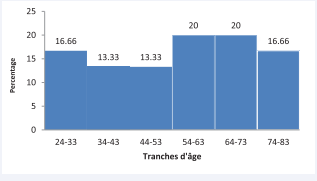

The mean age of patients in cardiogenic shock was 53.5 ± 17.56 years, with extremes of 24 and 78 years. Patients in the age range [54-73 years], accounted for 40% of the cases. Figure 1

Figure 1: Distribution of cardiogenic shock cases according to age range.

shows the distribution of patients by age group.

Housewives were the most represented (33.33%) and more than half of the patients (53.33%), had a medium socioeconomic level. Table 1 shows the distribution of patients by occupation

Clinical and paraclinical data

On physical examination, the mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 54.83 ± 32.47 mm Hg with extremes of 0 and 85 mm Hg. As for mean arterial pressure (MAP), the mean was 43.13 ± 25.98 mm Hg and extremes of 0 and 72 mm Hg.

Congestive heart failure was the most frequent, accounting for 73.33% of cases (22 cases), followed by left heart failure (five cases) and right heart failure (three cases).

| Profession | number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Home women | 10 | 33.33 |

| Civil server | 4 | 13.33 |

| Retired | 3 | 10.0 |

| Shopkeeper | 8 | 26.66 |

| Farmer | 3 | 10.0 |

| breeder | 2 | 6.66 |

| Total | 30 | 100 |

On ECG, sinus tachycardia was found in 21 patients (76.6% of cases) and complete tachyarrhythmia by atrial fibrillation in five cases. Table 2 shows the frequency of the different electrocardiographic abnormalities.

On cardiac Doppler echo, the mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 38.56 ± 19.37% with extremes of 15 and 72%. The mean cardiac index was 1.40 ± 0.32 l/min/m² with extremes of 0.63 and 1.80 l/min/m².

A disturbance of the global and segmental kinetics was observed in 21 patients. The mean Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was 46.27 ± 14.54 mm Hg with extremes of 27 and 85 mm Hg. PASP was elevated in 65% of patients. Table 3 shows the echocardiographic abnormalities found.

Shock Etiologies

The etiologies of shock were dominated by acute decompensation of pre-existing heart disease (19 cases), pulmonary embolism (six cases) and acute ST+ coronary syndrome (three cases). The underlying heart disease was dominated by ischemic heart disease in six cases, valvular heart disease in five cases, and hypertensive cardiomyopathy with secondary dilatation (three cases). Table 4 summarizes the etiologies of shock states as well as the underlying cardiopathies.

Treatment

The therapeutic modalities were case-specific. Dobutamine was administered in 76.66% of cases (23 patients), thrombolysis in five cases and pericardial puncture in two cases. External

| Electrocardiogram abnomalities | number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sinus tachycardia | 21 | 76.66 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 | 21.66 |

| Venticular primature beat | 9 | 30.0 |

| Atrial flutter | 2 | 6.66 |

| Necrosis Q wave Ondes | 2 | 6.66 |

| S1Q3T3 aspect | 2 | 6.66 |

| ST elevation | 1 | 3.33 |

| Left ventricular Hypertrophy | 13 | 43.0 |

| Right ventricular Hypertrophy | 1 | 3.33 |

| Anomalies échocardiographiques Doppler | number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Alteration of the LVEF | 20 | 66.67 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 20 | 66.67 |

| Tricuspide Anular Plane Systolic Excursion < 16 mm | 19 | 63.33 |

| Pericardial effusion of moderate size | 14 | 46.67 |

| Left ventricular severe global hypokinesia | 8 | 26.67 |

| Septal akinesia | 6 | 20 |

| Moderate global hypokinesia | 5 | 16.67 |

| Mild global hypokinesia | 2 | 6.67 |

| Pericardial effusion with collapse of the right heart chambers | 2 | 6.67 |

|

Etiologies of shock |

number | frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Acute decompensation | 19 | 63.33 |

| - Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 6 | 31.58 |

| - Valvular heart disease | 5 | 26.32 |

| - Dilated hypertensive cardiomyopathy | 3 | 15.79 |

| - Dilated cardiomyopathy | 3 | 15.79 |

| - Chronic pulmonary heart disease | 2 | 10.53 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 6 | 20 |

| ST+ acute coronary syndrome | 3 | 10 |

| Pericardial tamponade | 2 | 6.67 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 2 | 6.67 |

| Cardiothyreosis | 1 | 3.33 |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy | 1 | 3.33 |

| Infective endocarditis | 1 | 3.33 |

| Myopericarditis | 1 | 3.33 |

electric shock was performed in two cases.

Prognosis

Mortality was high, i.e. 56.7% of cases. It was 100% in valvular and ischemic heart disease.

In multivariate analysis, the predictive factors for death were LVEF < 18% ((OR =4.7; CI95 [1.25-9.23], p=0.0001)), dobutamine use ((OR =2.8; CI95 [1.05-6.93], p=0.001)) and mitral stenosis ((OR =10.5; CI95 [1.65-15.20], p=0.0001)).

DISCUSSION

The frequency of cardiogenic shock in our department was 7% in the department and accounted for more than 63% of the activity in cardiac intensive care. It is known that cardiogenic shock complicates 7 to 10% of infarctions [3], but when other causes are considered, the prevalence of shock can reach 15%, especially in intensive care units [9]

The mean age was 53.5 ± 19.04 years with extremes of 24 and 78 years. The age range of [54-73 years], was the most represented. Our population was relatively younger than that observed in European series where the mean age was 60 years and 61 years by Laleeve C et al., respectively [10,11]. This difference could be explained by the higher life expectancy and the later onset of ischemic and hypertensive heart disease related to the improved management of pathologies such as coronary artery disease and hypertension in industrialized countries. The persistence of rheumatic valve diseases in our countries, which affect mainly young subjects, and the limited access to cardiac surgery are contributing factors.

Two (02) of our patients presented a rhythmic cardiogenic shock such as atrial flutter. Rhythmic complications in advanced cardiomyopathy or valvulopathy are regularly reported by several studies.

The rhythm disorder most observed in our study was sinus tachycardia. Tachycardia is part of the body’s compensatory efforts in the presence of heart failure or shock.

In our study, we observed a mean LVEF of 38.56% with extremes of 15 and 72%. These values are very close to those published by Laleeve C. which were 35.8% for the mean and extremes of 15 and 60% [11]. Our data are also quite superposable to the mean LVEF of Jean-Baptiste S. which was 32% [8]. Our study showed a significant association between low LVEF values and in-hospital mortality from cardiogenic shock. Engstrom et al. demonstrated that an LVEF below 40% was associated with an unfavorable outcome in an ischemic cardiogenic shock population. LVEF was also classified as an independent risk factor for mortality by the SHOCK study [12,13]. However, the studies by Jean-Baptiste and Laleeve C. did not share this significant correlation between LVEF and in-hospital mortality in cardiogenic shock [8,11].

Left ventricular filling pressures were elevated in 76% of patients. This is explained by the predominant left ventricular involvement in our series. This parameter of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction is a recent index to be taken into account in the evaluation of left ventricular performance. The use of this parameter in our study allowed us to find a statistically significant association between elevated left ventricular pressures and inhospital mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock.

The mean cardiac index of our population was 1.36 l/min/m² compared to 2.1 l/min/m² and 2.4 l/min/m² found respectively by Jean-Baptiste S. and Laleeve C. [8,11]. As for cardiac output, it is a robust predictive factor of mortality in cardiogenic shock published by many studies and in particular the SHOCK study [12, 13]. Our mean cardiac power was 0.22 W. Other studies on cardiogenic shock that have systematically integrated fairlyexhaustive echocardiographic data useful in emergencies, such as those by Jean-Baptiste S., mention a value of 0.40 W [8]. Our cardiac power is thus lower than that found by Jean-Baptiste S.

These two fundamental hemodynamic parameters of monitoring in cardiogenic shock did not show a statistically significant association with hospital mortality in our study nor in the works of Jean-Baptiste S. and Laleeve C. [8, 11]. The correlation between mortality and these two indices in the problem of cardiogenic shock, whether ischemic or not, affirmed by large cohort multicenter studies, but not corroborated by our series, is probably explained by the smaller size of our populations. Indeed, we collected 30 patients in 6 months. Jean-Baptiste S. and Laleeve C. included 55 and 94 patients, respectively [8,11].

Bedside echocardiography during our work has been particularly beneficial to some of our hospitalized patients in terms of etiological diagnosis of shock and especially in terms of the immediate initiation of a specifically adapted treatment. Two examples are worth mentioning.

The first case is a patient admitted with dyspnea and right heart failure syndrome with signs of shock. Emergency echocardiographic exploration contributed to the diagnosis of pericardial tamponade and immediately favored pericardial evacuation. This emergency treatment, which was carried out without accident or incident, quickly restored good hemodynamics.

The second case is another patient admitted with dyspnea and dizziness, in whom the examination revealed only an impenetrable blood pressure and cold extremities. The mobile echocardiograph was then quickly brought to the patient’s bed. The spectacular images obtained with this valuable device were those of mobile thrombi looping from the right atrium to the right ventricle, dilated right heart chambers, paradoxical interventricular septum, elevated pulmonary artery pressure, and collapsed TAPSE. Although a thrombus image could not be visualized in the lumen of the pulmonary arterial tree, this echocardiogram in the right heart chambers of a patient in shock without left ventricular dysfunction or pericardial effusion is almost pathognomonic of a pulmonary embolism with a high mortality risk. This diagnosis was thus made and a therapeutic sanction such as thrombolysis by streptokinase was immediately instituted without first resorting to angioscanning of the pulmonary arteries for a formal diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. This therapeutic attitude based solely on clinical and especially echocardiographic elements is included in the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology [14]. After thrombolysis, the shock state was stopped and the thrombi in the right cavities disappeared.

The contribution of this imaging modality to the etiological diagnosis of shock states, sometimes accompanied by the implementation of an adequate treatment, is shared by several authors [8,11,15].

In the study of Gaëlle A. in Rennes, France, 23% of patients, i.e. 7 out of 27, presented a pericardial effusion but only one patient presented an obstructive shock on tamponade, related to a fissure of the free wall of the left ventricle following an inferior infarction (15). The patient was not drained in the emergencyroom and was transferred to the Nantes University Hospital for more appropriate management.

The etiologies of cardiogenic shock are dominated in our study by dilated cardiomyopathy. The predominance of this etiology is found in the work of Jean-Baptiste S., who studied only non-ischemic cardiogenic shock (8). Its proportion was 47%.

Many high-powered studies on cardiogenic shock, such as the SHOCK and GUSTO studies published in the literature, refer to cardiogenic shock complicating an acute coronary syndrome [12,13,16].

The overall mortality in our series was 56.66%. Our rate is higher than those of Jean-Baptiste S. and Laleeve, which were 46.8% and 50.9%, respectively [8,11]. Mortality in the subgroup of cardiogenic shock on acute coronary syndrome was 100% in our series and also in that of Beye SA. in Ségou, Mali [17]. On the other hand, Nguetan R. in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, recorded 66% of deaths in this category [18]. Our higher mortality is probably related to the difficulty of systematically optimizing management in relation to the limited technical facilities. For example, we do not have a coronary angiography and hemodynamics unit, let alone a cardiothoracic surgery wing and a resuscitation service with heavy assistance techniques.

In our study there was a statistically significant association between the rate of death and the degree of decline in left ventricular ejection fraction and the degree of elevation of left ventricular filling pressures. This corroborates the data in the literature, in particular the significant decrease in LVEF recognized by the SHOCK study as an independent predictive factor of mortality [12,13].

CONCLUSION

Our study has shown the importance of echocardiography in the management of patients in cardiogenic shock. It offers a better precision of the nature of cardiogenic shock, thus guiding its better management. It is therefore imperative that the use of mobile Doppler echocardiography be generalized in the services that manage emergencies. However, therapeutic resources must be available and accessible to all patients concerned in an emergency.

REFERENCES

2. Califf R.M., Bengtson J.R. Cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 1994; 330: 1724-1730.

8. Jean-Baptiste S. Pronostic et prise en charge du choc cardiogénique non ischémique en réanimation médicale Thèse médecine spécialisée Université Henri Poincaré, Nancy-I 2011. N°3740, 134.

14.The task force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European society of cardiology 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

15.Allaire G. Etude prospective évaluant l’interet de l’échocardiographie precoce dans la prise en charge des états de choc aux urgences Thèse de médecine spécialisée université de Nantes, année 2006 ; 84.

18.N’Guetta R, Seka R, Ekou A, Anzouan-Kacou JB, N’Cho-Mottoh MP, Adoh AM. Percutaneous intervention in western Africa: experience of Ivory Coast. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2011; 22: 16.